12

Innovation in Action

- Learning Objectives

- To identify some of the different techniques some successful companies use for innovation activities

- To understand that not all companies use the same innovation techniques

INTRODUCTION

There is no clear-cut template for all the activities that an organization must do for continuous innovation to occur. Even though there might be commonly used innovation tools or an innovation canvas, every company has their own business plan, organizational structure and culture for innovation.

All of the companies discussed in this chapter have different approaches to innovation. They all have innovation strengths and weaknesses. For each company, only a few of their innovation attributes related to their unique strengths are being discussed as examples of information presented in earlier chapters.

INNOVATION IN ACTION: APPLE

“Was [Steve Jobs] smart? No, not exceptionally. Instead, he was a genius. His imaginative leaps were instinctive, unexpected, and at times magical. […] Like a pathfinder, he could absorb information, sniff the winds, and sense what lay ahead. Steve Jobs thus became the greatest business executive of our era, the one most certain to be remembered a century from now.

History will place him in the pantheon right next to Edison and Ford. More than anyone else of his time, he made products that were completely innovative, combining the power of poetry and processors. With a ferocity that could make working with him as unsettling as it was inspiring, he also built the world's most creative company. And he was able to infuse into its DNA the design sensibilities, perfectionism, and imagination that make it likely to be, even decades from now, the company that thrives best at the intersection of artistry and technology.”

— Walter Isaacson, Steve Jobs

When people think about companies that have a history of continuous innovation, they usually start with Apple. But what many people do not recognize is that the path leading to continuous innovation success may be strewn with some failures, roadblocks, challenges, and possibly lawsuits such as Apple encountered with Microsoft and Samsung.

Background

Some of Apple's successes include the Macintosh computer, iPod, iPhone, iPad, Apple Watch, Apple TV, HomePod, Software, electric vehicles, and Apple Energy. But there is also a dark side of unsuccessful consumer products that were launched during the 1990s, such as digital cameras, portable CD audio players, speakers, video consoles, and TV appliances. The unsuccessful consumer products were not the result of an innovation failure but from unrealistic market forecasts.

Successful innovations increase market share and stock prices, while unsuccessful products have the opposite effect. Apple was highly successful with the Macintosh computer from 1984 to 1991. From 1991 to 1997 Apple struggled financially due to limited innovation. Apple returned to profitability between 1997 and 2007. In 2007, Apple's innovations in mobile devices were a major part of its astounding success.

Innovation often creates legal issues over the ownership and control of intellectual property. The growth of the Internet created a problem of piracy in the music industry. Steve Jobs commented on Apple's success in the music business, stating that “Over one million songs have now been legally purchased and downloaded around the globe, representing a major force against music piracy and the future of music distribution as we move from CDs to the Internet.”

Apple used and continues to use several different types of innovation. Some products use incremental innovation, such as updated versions of cell phones, whereas other products appear as radical innovation. Apple also uses both open and closed innovation. For open innovation activities, Apple has created a set of Apple Developer Tools to make it easier for the creation of products to be aligned to Apple's needs.

Apple also created innovations in its business model, which was designed to improve its relationship with its customers. Apple created a retail program that used the online store concept and physical store locations. Despite initial media speculation that Apple's store concept would fail, its stores were highly successful, bypassing the sales numbers of competing nearby stores, and within three years reached US$1 billion in annual sales, becoming the fastest retailer in history to do so. Over the years, Apple has expanded the number of retail locations and its geographical coverage, with 499 stores across 22 countries worldwide as of December 2017. Strong product sales have placed Apple among the top-tier retail stores, with sales over $16 billion globally in 2011.

Apple created an innovation culture that gave people the opportunity to be creative. Unlike other cultures where executives assign people to innovation projects and then sit back waiting for results to appear, Steve Jobs became an active participant in many of the projects. Numerous Apple employees have stated that projects without Jobs's involvement often took longer than projects with it.

At Apple, employees are specialists who are not exposed to functions outside their area of expertise. Jobs saw this as a means of having “best-in-class” employees in every role. Apple is also known for strictly enforcing single-person accountability. Each project has a “directly responsible individual,” or “DRI” in Apple jargon. In traditional project management, project managers often share the accountability for project success and failure with the functional managers that assign resources to the project.

To recognize the best of its employees, Apple created the Apple Fellows program, which awards individuals who make extraordinary technical or leadership contributions to personal computing while at the company. This is becoming a common practice among companies that have a stream of innovations. Disney created a similar society called “Imagineering Legends” to recognize innovation excellence.1

Conclusion

Continuous successful innovation is possible if the firm has a tolerance for some failures and recognition that the marketplace may not like some of the products. Also, the company's business model may change, as happened with the opening of Apple stores.

INNOVATION IN ACTION: FACEBOOK

Some companies boast of the size of their user base for their innovations in the thousands or hundreds of thousands. But other companies, such as Facebook, must satisfy the needs of possibly hundreds of millions of end users. To do this successfully, and remain innovative, open source innovation practices are essential.

Background

Many of Facebook's innovations come from open source innovation, crowdsourcing and the use of platforms. Facebook launched the Facebook Platform on May 24, 2007, providing a framework for software developers and other volunteers to create applications that interact with core Facebook features. A markup language called Facebook Markup Language was introduced simultaneously; it is used to customize the “look and feel” of applications that developers create. Using the Platform, Facebook launched several new applications, including Gifts, which allows users to send virtual gifts to each other, Marketplace, allowing users to post free classified ads, Facebook events, giving users a means to inform their friends about upcoming events, Video, which lets users share homemade videos with one another, and a social network game, where users can use their connections to friends to help them advance in games they are playing. Many of the popular early social network games would eventually combine capabilities. For instance, one of the early games to reach the top application spot, Green Patch, combined virtual Gifts with Event notifications to friends and contributions to charities through Causes.

Third-party companies provide application metrics, and several blogs arose in response to the clamor for Facebook applications. On July 4, 2007, Altura Ventures announced the “Altura 1 Facebook Investment Fund,” becoming the world's first Facebook-only venture capital firm.

Applications that have been created on the Platform include chess, which allows users to play games with their friends. In such games, a user's moves are saved on the website allowing the next move to be made at any time rather than immediately after the previous move.

By November 3, 2007, seven thousand applications had been developed on the Facebook Platform, with another hundred created every day. By the second annual developers conference on July 23, 2008, the number of applications had grown to 33,000, and the number of registered developers had exceeded 400,000. Facebook was also creating applications in multiple languages.

Mark Zuckerberg said that his team from Facebook is developing a Facebook search engine. “Facebook is pretty well placed to respond to people's questions. At some point, we will. We have a team that is working on it,” said Mark Zuckerberg. For him, the traditional search engines return too many results that do not necessarily respond to questions. “The search engines really need to evolve a set of answers: 'I have a specific question, answer this question for me.'”

Conclusion

Facebook appears to have successfully managed open source innovation and developed strategic partnerships with application providers given the fact that it has more than 400,000 providers.

INNOVATION IN ACTION: IBM

Background

According to the Incumbents Strike Back—19th C-Suite study from IBM Institute for Business Value, in order for organizations to compete in today's rapid-fire world, they are pressured to bring high-quality, differentiated products and services to market quickly. But the push to “get something out there” can lead to experiences that aren't relevant to real customer needs. If you miss the mark, you may not get a second chance. Traditionally, designers and developers have had to operate within isolated functional areas. By building multidisciplinary teams and combining a design thinking approach with agile methodologies, you can release efficiently and increase the likelihood that a customer's first impression will be a good one.

Across a growing number of industries, solution discussions are becoming centered on customer experience as opposed to the traditional product focused lens.

Jim Boland, IBM's Project Management Global Center of Excellence Leader, is clear that IBM's project managers need to be front and center in these discussions. Their role is expanding, and the need to continuously adapt is the new norm. The traditional way of thinking—understanding your deliverables, your time to deliver and the budget you have—although still critical, may not be sufficient to ensure success.

Collaboration and agility need to sit comfortably with proven practices such as scope and financial management.

If you think about this statement, it presents quite a challenge—we are asking our project managers to be flexible enough to continuously listen and collaborate to our customers changing needs and adapt the solution accordingly, while in parallel continue managing the deliverables (including scope, time, and budget). Augmenting traditional project management skills with skills such as collaboration, agility, design thinking, and resilience become paramount.

Establishing a high level of trust throughout the journey is critical, not just trust across teams and stakeholders, but, trust in the process and the journey itself.

IBM has implemented a set of tools, techniques, learnings, and methods to enable their project managers and set them up for success in this new environment. An example of this was the establishment of academies within IBM such as the agile and design thinking academies, supported by IBM's global on-demand learning platform, YourLearning, enabling a personalized learning journey for everyone in the company.

IBM is also taking this to our clients through the establishment of the IBM Garage, which is a new way of working where IBM experts, including project managers, co-create with clients in a customizable space. It's a place where you can experiment with big ideas, acquire new expertise and build new enterprise-grade solutions with modern and emerging technologies.

Case Study #1

This IBM case study, provided by Galen K. Smith, Cognitive Supply Chain Accelerator and IBM-certified executive project manager at IBM, demonstrates how innovation can and should be a part of project management. In this case, the project team chose to follow some of the agile and design thinking principles mentioned already, orchestrated by project managers in leadership roles facilitating the learning and implementation throughout the project life cycle.

Requirements-gathering started with user interviews, which resulted in the identification of three personas—supply chain specialist/buyer, operational commodity manager, and supply chain leaders. These personas defined the user groups that would participate in determining the deliverables for the minimum viable product (MVP) and first release. It was these three personas that the team focused on to understand their user experience and pain points and how to deliver a better user experience and achieve the business objective.

With the user groups defined, the next step was a design thinking workshop with key members of the project team—product owner, UX (user experience) designer, business lead, and executive sponsor attending along with 13 actual users from each of the personas. The facilitator was an Agile project manager who led them through a day of design thinking practices designed to fully understand the current situation for each persona and their pain points along with ideation of ideas for a better UX. These ideas were prioritized, and the team moved into storyboarding, which applies the ideas into a new to-be scenario. The day ended with attendees creating their own paper prototype that envisioned how the UI (user interface) would look and feel, what data is needed and how to show it, and how the screens interact to deliver their vision of the desired user experience.

This approach was run in an open environment that fostered engagement by all, ignored rank, and ensured every attendee's input was heard. The workshop included creativity exercises that targeted opening the creative side of the brain, which, along with the method of collaboration and inclusion, resulted in elevating the overall creativity of the work. This creativity provided dramatically more innovative results, as seen in the wealth of ideas portrayed in the paper prototype designs.

The project managers involved played the roles of product owner, business analyst, and user SME lead and continued this innovative atmosphere after the workshop by infusing creativity, experimentation, user engagement, and feedback in the regular calls with users (twice/week), management (monthly), and the executive sponsor (weekly). With the support of the executive sponsor and management team, the project managers cultivated a cultural change in the organization and sustained it with fun events that focused on users. These events included running innovation jams, Ideation blogs, sser engagement games surrounding tool learning and utilization, celebrating experiments, and recognizing folks who contributed the ideas for new function when it gets deployed.

“How is this managing innovation?” asks Smith who summarises by stating that ideas generate innovation, and ideas flow strongly only when users feel their ideas are being heard and executed. Many avenues were opened to bring in ideas both initially and on an ongoing basis and the project leaders—product owner (PM), user lead SME (PM), and business lead—purposely communicated back to all users where the ideas came from and when they were deployed to ensure users could see how their ideas influenced the design and deliverables of the project.

Case Study #2

In this case study, Gary Bettesworth, a CICS (customer information control system) project manager at IBM, explains how a similar approach was so successful in transforming a traditional software development process.

CICS transaction server (TS) is a powerful mixed language application server, which runs on the IBM Z platform. It is used extensively in the finance and retail sectors for business-critical services, providing online transaction management and connectivity. It can process incredibly high workloads in a scalable and secure environment.

This software, which celebrates its 50th anniversary in 2019, was developed using a traditional waterfall process for most of its life. However, the waterfall development process and long development lifecycles can sometimes be slow and inflexible.

In addition, customer demands to be more agile and to consume software faster, due to the need to respond to constantly changing and competitive marketplaces, driven by technological innovation, required a transformation of the team's software development and management process.

Over the last 10 years, the project team have been on a journey culminating in the use of project management and delivery process and tools, which support the concepts of Agile, DevOps, and Enterprise Design Thinking.

According to Bettesworth, the Enterprise Design Thinking method helps the team validate that they are building the right software by implementing activities like as-is and to-be scenario mapping, empathy mapping and interviews, to fully engage with users and understand their personas and needs. This combined with agile practices (time-boxed iterations, frequent code delivery and feedback, code demonstrations/playbacks, small multidisciplined subteams, story points and burndown charts, prioritized backlogs) and supporting Agile tooling has completely changed the culture of the CICS TS project team. The whole project team is empowered and self-directed, which supports innovation during the software development process, with project management taking on a servant leadership role to help and guide where necessary. Plans are no longer fixed, with adjustments or pivots being made regularly based on stakeholder feedback and a continuous assessment of the market. Changes to the delivery process are also made by project team members continuously throughout the project.

Innovation has also been essential to enable the team to modernize all its tooling and create a DevOps end-to-end automation pipeline built in a modular manor. This continuous integration pipeline enables code to be rapidly built, deployed and tested as soon as it has been developed. The ability to quickly build and test software has been essential to frequently deliver new capability to project stakeholders. Live dashboards enable code delivery and project status to be viewed by internal stakeholders, including the project manager and are used as the basis for project status meetings.

These are just two out of thousands of examples of projects being run across IBM where project managers are changing their approach to how they launch, manage and close projects.

Case Study #3

Carlos Carnelós, IBM's Technical Support Services Delivery Transformation Lead in Latin America, and who has been working in the area of IT Automation for the past four years, states that innovation lies in the project deliverables, the technologies deployed and the newer ways we are doing business. In his experience, project management techniques are becoming a mix of traditional and Agile and use design thinking as a methodology for defining scope and prioritizing what and when functions get delivered.

Conclusion

In summary, Jim Boland's opinion is that good project managers are equal parts project managers, consultants, change agents, and innovators. As the term hybrid job becomes more and more standard practice in the future, our project managers will have to mix their traditional PM skills with new age skills such as design thinking, data analytics, and so on. This statement holds through for many job roles and it's just as important for employees who are not project managers to learn project management skills. Innovation will be a constant in this new hybrid world.

INNOVATION IN ACTION: TEXAS INSTRUMENTS

When companies recognize the need for continuous innovation, they are often at a loss as to where to begin. Some companies tend to focus on technology and organizational restructuring. Texas Instruments quickly identified that starting with people and an organizational culture that supports innovation can accelerate the process.

Background

Most people seem to believe that innovation project management begins with the development of a project management methodology. Furthermore, they often make the fatal mistake of believing that the development of a project management methodology is the solution to all their ailments for traditional and innovation projects. While this may be true in some circumstances, companies that appear to be excellent in project management realize that people execute methodologies and that the best practices in innovation and traditional project management might be achieved quicker if the focus initially is on the people rather than the tools. Therefore, the focus should be on the culture.

One way to become good at project management is to develop a success pyramid. Every company has their own approach as to what should be included in a success pyramid. Texas Instruments recognized the importance of focusing on people as a way to accelerate innovation project success. Texas Instruments developed a success pyramid for managing global innovation projects. The success pyramid is shown in Figure 12-1.

Figure 12–1. The Success Pyramid.

A spokesperson at Texas Instruments describes the development and use of the success pyramid for managing global projects at Texas Instruments:

By the late 1990s, the business organization for sensors and controls had migrated from localized teams to global teams. I was responsible for managing 5–6 project managers who were in turn managing global teams for NPD (new product development). These teams typically consisted of 6–12 members from North America, Europe, and Asia. Although we were operating in a global business environment, there were many new and unique difficulties that the teams faced. We developed the success pyramid to help these project managers in this task.

Although the message in the pyramid is quite simple, the use of this tool can be very powerful. It is based on the principle of building a pyramid from the bottom to the top. The bottom layer of building blocks is the foundation and is called “understanding and trust.” The message here is that for a global team to function well, there must be a common bond. The team members must have trust in one another, and it is up to the project manager to make sure that this bond is established. Within the building blocks at this level, we provided additional details and examples to help the project managers. It is common that some team members may not have ever met prior to the beginning of a project, so this task of building trust is definitely a challenge.

The second level is called sanctioned direction. This level includes the team charter and mission as well as the formal goals and objectives. Since these are virtual teams that often have little direct face time, the message at this level is for the project manager to secure the approval and support from all the regional managers involved in the project. This step is crucial in avoiding conflicts of priorities from team members at distant locations.

The third level of the pyramid is called accountability. This level emphasizes the importance of including the values and beliefs from all team members. On global teams, there can be quite a lot of variation in this area. By allowing a voice from all team members, not only can project planning be more complete but also everyone can directly buy into the plan. Project managers using a method of distributed leadership in this phase usually do very well. The secret is to get people to transition from attitude of obligation to a willingness of accepting responsibility.

The next level, called logistics, is where the team lives for the duration of the project and conducts the day-to-day work. This level includes all of the daily, weekly, and monthly communications and is based on an agreement of the type of development process that will be followed. At Texas Instruments, we we have a formal process for NPD projects, and this is usually used for this type of project. The power of the pyramid is that this level of detailed work can go very smoothly, provided there is a solid foundation below it.

Following the execution of the lower levels in the pyramid, we can expect to get good results, as shown in the fifth level. This is driven in the two areas of internal and external customers. Internal customers may include management or may include business center sites that have financial ownership of the overall project.

Finally, the top level of the pyramid shows the overall goal and is labeled “team success.” Our experience has shown that a global team that is successful on a one- to two-year project is often elevated to a higher level of confidence and capability. This success breeds added enthusiasm and positions the team members for bigger and more challenging assignments. The ability of managers to tap into this higher level of capability provides competitive advantage and leverages our ability to achieve success.

Conclusion

At Texas Instruments, the emphasis on culture not only benefited their innovation initiatives but also resulted in best practices that supported other initiatives. It is unfortunate that more companies do not realize the importance of this approach.

INNOVATION IN ACTION: 3M

Companies often struggle with how to bring the workforce into the innovation process. In some companies, workers believe that only the R&D group or any other innovation groups are responsible for coming up with innovation ideas and exploiting them. 3M took a different approach and set the standard on how to involve the entire company.

Background

Companies that are highly successful at innovation use innovation as the driver for sustained corporate growth. 3M Corporation is prime example of innovation in action. Most researchers agree that 3M's success emanates from their corporate culture that fosters an innovation mindset. As stated by Irving Buchen (2000):

3M announced that all employees were free to spend up to 15 minutes each working day on whatever ideas they wanted to work on. The only restriction was that it could not be at the expense of their regular assignments. They did not have to secure approval for their project. They did not have to tell anyone what they were working on. They could bunch their l-minute segments if they needed more solid blocks of time. They did not have to produce anything to justify or pay back the time taken. What was the result? There was electricity in the air. Employees came earlier and stayed later to extend their innovation time. Many walked around with a weird smile of mischief and even fun across their face; some even began to giggle. But they were also enormously productive. Scotch tape came out of this ferment; so did Post-its. Perhaps equally as important, morale was given an enormous lift; general productivity was higher; teams seemed to be closer and working better together; the relationships between middle-level managers of different divisions seemed to improve. In short, it was a win-win situation. The innovative gains were matched by a new spirit that changed the entire culture.

Companies such as Google and Hewlett-Packard have programs similar to 3M's 15 percent time program. 3M's program was initiated in 1948 and has since generated many of the company's best-selling products, 22,800 patents, and annual sales of over $20 billion.

There are several distinguishing characteristics of the 3M culture, beginning with employee encouragement for innovation. Employees are encouraged to follow their instincts and take advantage of opportunities. 3M provides forums for employees to see what others are doing, to get ideas for new products, and to find solutions to existing problems. The culture thrives on open communication and the sharing of information. Employees are also encouraged to talk with customers about their needs and to visit 3M's Innovation Centers.

Strategic direction is another characteristic of the 3M culture. Employees are encouraged to think about the future but not at the expense of sacrificing current earnings. Using the “Thirty Percent Rule,” 30 percent of each division's revenues must come from products introduced in the last four years. This is tracked almost religiously and forms the basis for employee bonuses.

Funding sources are available to employees to further develop their ideas. Seed money for initial exploration of ideas can come from the business units. If the funding requests are denied, employees can request corporate funding.

Rewards and recognition are part of 3M's innovative culture. A common problem facing many companies is that scientists and technical experts believe that the “grass is greener” in management than in a technical environment. 3M created a dual ladder system whereby technical personnel can have the same compensation and benefits as corporate management by remaining on a technical ladder. By staying on the technical ladder, people are guaranteed their former job even if their research project fails.

Similar to Disney and Apple, 3M created the Carlton Society, named after former company president Richard P. Carlton, which recognizes the achievements of 3M scientists who develop innovative new products and contribute to the innovation culture.

One of the most significant benefits of the 3M culture is in recruiting. Workers with specialized skills are sought after by most companies and the culture at 3M, which offers a significant amount of “freedom” for innovation, helps them attract talented employees.

Conclusion

3M's success set the standard that others have copied on how to involve the entire organization into innovational thinking. All employees must be made aware of the notion that they can contribute to innovation and their ideas will be heard.

INNOVATION IN ACTION: MOTOROLA

For more than 90 years, Motorola has been recognized as a synonym for innovation. Motorola's strength has been in technical innovations in the communications and semiconductor industries but has been expanded to other industries. Motorola set the standard for getting close to the end users during innovation activities and the need to understand the business model of the customers.

Background

In previous chapters, we discussed the importance of getting to close to the customers to understand their needs. In most companies, innovation research is simply asking customers what their needs might be now and in the future. Motorola carries their research much further. Motorola conducts “deep” customer research using their design research and innovation teams to articulate not only how users work with Motorola's products but also how customers run their business processes and what their needs will be in the future. Motorola also observes how customers use their products.

Motorola's research goes beyond simply understanding how the product is being used. It also includes an understanding of why the product is essential to the customer's business success and how the product fits into the customer's business model. This allows Motorola to perform targeted innovation. Customer knowledge is not based on just the end user's requirements. Understanding the business aspects of a product solution can give industrial design groups the opportunity to drive product development direction.

Motorola's generative research is driven by customer and partner interviews as well as observational research. As stated by Graham Marshall:

Based on the first round of customer visits and generative research, the team identifies specific customers to revisit during the product definition phase. At this time the researcher will bring sample models that demonstrate form, features, and functionality. The product definition phase helps the team clearly define and test the right product fit before there is a commitment to development.

We use model toolkits and storyboards to communicate potential design directions with our customers. We can better see the complexity of the customer's needs by posing specific questions: “What information do you need to display? How much information do you need to key in? How well lighted is your space? Is the product used in the storeroom or the storefront, or both? How far do you need to carry or move the product or the device to complete a transaction?”

Motorola also performs validation to ensure that the focus is on a customer solution. As stated by Marshall:

During the course of the development program, the Innovation and Design team needs to validate the integrity of the gathered information, product direction, and development trade-offs. This ensures that, as product development progresses, the design remains targeted on the customer's needs.

Conclusion

By understanding the customer's business and maintaining close customer contact, Motorola has demonstrated the benefits that can be derived from innovative customer-focused solutions. Simply stated, Motorola has evolved into a targeted business solution provider.

INNOVATION IN ACTION: ZURICH NORTH AMERICA

Three Tips for Managing Successful Innovation Projects

Technology is driving change across major industries around the globe at a faster pace than ever before. In response, businesses must develop a point of view on emerging trends and intentionally invest in innovation to remain competitive. New technology often introduces new risks to an organization. To mitigate these risks, the Zurich North America (ZNA) PMO recommends these three tips for managing innovation projects.

1. Establish Success Criteria Up Front

With innovation comes ambiguity. Project teams and management must be comfortable not having all the answers. There should, however, be agreed on criteria for how project success will be measured. Success criteria gathered from a business perspective helps ensure focus on outcomes that impact top and bottom lines. There needs to be flexibility and tolerance for accepting risk, as business outcomes will evolve as more is known about the new technology. Innovation project success starts with an open discussion on what leaders hope to achieve from the project. Established success criteria allow project leaders to manage expectations both short and long term.

Innovation thrives where there is trust and collaboration between business and IT as teams navigate new territory. Well-defined success criteria discussed early and shared often helps to keep everyone aligned and on the same path.

2. Execute a Proof of Technology to Prove the Solution Meets the Business Need

New technology solutions may at first appear easy and relatively inexpensive, so it's important to ask the right questions. A proof of technology (PoT) can help validate that a proposed solution is capable of meeting the business need using the expected business processes and data sources. The key to a successful PoT is proper planning. This includes getting the IT resources lined up, including engineers and servers, along with securing the necessary SMEs (subject matter experts) for the duration of the PoT. It's also important to identify and mitigate risks especially those related to data privacy and information security. The size of a PoT should be scaled to be manageable while providing enough information to make decisions quickly. Quan Choi, Enterprise Architect at Zurich North America noted, “With the right planning, actually running the PoT can be relatively short, as short as a week, though the planning may have taken months.”

Quan was clear to point out that PoTs generally would not integrate into live systems, reducing the impact as well as the costs when compared to large-scale integration. However, PoT results should also consider the impacts of full integration. This will provide a clearer picture of additional work and investment needed for a decision to be made regarding a full implementation.

Kandace Spotts, head of PMO at Zurich North America, shared how PoTs have enabled decision making while minimizing risk. “Designating small funding amounts for project teams to try new technologies has allowed our leaders to gain insights into technical capabilities quickly. Through PoTs, we minimize our financial risk, because we find out if the solution is fit for purpose for our business needs before we invest heavily.”

3. Use Stage Gates to Assess Progress and Make Swift Decisions about Next Steps

Stage gates provide a transparent way of gauging progress and readiness to move to the next sprint or phase. During a stage gate, results are reviewed against success criteria so an informed strategic assessment can be made. The ability to stop a project and quickly move to the next innovation opportunity is critical. Stage gates also serve as a vehicle for sharing of best practices and lessons learned. This allows project teams the ability to gain experience in new technologies, while minimizing the financial risk to the organization.

Applying these three tips will help to reduce risks on innovation projects while keeping teams focused on successful business outcomes.

INNOVATION IN ACTION: UNICEF USA

Previously, we discussed companies like Apple, Facebook, and 3M, where innovation is driven by profitability, market share, and dividend payouts. However, there is another side of innovation that is driven by humanitarian concerns rather than financial concerns.

Background

UNICEF Kid Power is the world's first Wearable-for-Good®, named one of Time magazine's 25 Best Inventions in 2016,2 and one of the largest education technology programs serving high-need elementary schools in the United States. Kid Power uniquely taps into kids' intrinsic desire to help others by using wearable technology to convert their physical activity to real-life impact. By getting active with a UNICEF Kid Power Band, kids earn points and unlock funding from partners, which UNICEF uses to deliver packets of therapeutic food for severely malnourished children. The more kids move, the more points they earn, the more children they help.

Launched in 2014 in the United States, UNICEF Kid Power aims to inspire an entire generation of American children to grow up as healthy and globally aware citizens, getting active to help end severe malnutrition around the world. During the first three years of Kid Power, the venture's startup phase, May 2014 to May 2017, Kid Power scaled from a pilot in 7 classrooms in a single city to almost 7,000 classrooms in 1,600 cities and towns in 49 states across the United States. In doing so, Kid Power engaged hundreds of thousands of kids who collectively walked over 100 billion steps to unlock enough funding for UNICEF to deliver enough therapeutic food packets to help save the lives of 52,000 severely malnourished children.

During the startup phase of Kid Power, the innovation program grew from a simple app connected to off-the-shelf step counters being tested in seven classrooms, to a nationwide technology program consisting of proprietary hardware, a scalable mobile app and web front-end, and a rich library of standards-aligned classroom content, all of which were designed to be effective in high-need classrooms with no computers, in schools with no wifi, for students who didn't have access to a smartphone at home.

To scale up from 7 classrooms to 7,000, the program dramatically evolved from a city-based implementation driven with a single institutional stakeholder (i.e., the city administration consisting of the mayor's office and the Department of Education) to a grassroots movement with thousands of individual educators. During the project, the Kid Power team grew from 2 individuals in New York to a distributed team consisting of 10 employees, 10 contractors, and 3 agencies. To execute the project, the team implemented a version of scaled Agile, which combined Scrum methodology with short and medium time frames to allow fast-moving product development and marketing teams to work in a synchronized manner with slower-moving educator outreach and school implementation teams.

Stakeholders

The primary stakeholders for the project (the startup phase of UNICEF Kid Power) were elementary school educators and their students in high-need schools in the United States. By May 2017, Kid Power had scaled up to serve 7,000 educators from 1,600 cities and towns across 49 states, reaching students from a wide range of racial and ethnic backgrounds in both urban and rural communities.

The secondary stakeholders for the project were UNICEF USA management team and board, as well as internal marketing and engagement teams.

Creating an Innovation Culture

Development of an Effective Team and Promoting a Culture of Innovation

To execute the project, the UNICEF Kid Power team developed a unique form of Scaled Agile Framework, which followed Scrum methodology but combined short and medium time frames to allow fast-moving product development and marketing teams to work in a synchronized manner with slower moving educator outreach and school implementation teams.

To do so, all teams worked in six-week cycles, which kicked off with a group planning exercise to define priorities, user stories and deliverables for the cycle across all teams. While the slower moving teams executed their work in these six-week cycles, allowing sufficient time for stakeholder engagement and feedback, the faster moving teams executed their work in two-week sprints (fitting three such sprints into each six-week cycle), enabling rapid learning and iteration while ensuring alignment with the full Kid Power team.

For some aspects of the project, the Kid Power team relied on support from functional teams from other parts of UNICEF USA. While the Kid Power team was working in relatively short cycles and sprints with rigorous upfront planning and independent execution by individuals, the wider UNICEF USA organization was unfamiliar with agile concepts and worked in a traditional/waterfall manner. Initial excitement and curiosity about Agile from other teams gradually gave way to concern and resistance, as the differences in pace and culture began creating stress and tension. The Kid Power team overcame these challenges by creating an “interface” for the wider organization that allowed colleagues in other teams to engage with Kid Power without having to participate in the Agile ceremonies and way of working. That interface consisted of two main elements:

- A creative and operational brief, which took a form familiar to the rest of the organization, was emitted from each cycle planning session and shared with each outside team that needed to contribute to or were dependent on Kid Power activities. This allowed outside team members who were working on multiple projects to be able to participate in Kid Power on their own terms, while slowly being exposed to Agile and being able to appreciate it without being burdened by it.

- An online Scrum board which was accessible to the entire organization and was shared with all staff after each Sprint planning session. This created a high degree of transparency, and allowed any colleague who had a need or interest for more detail to quickly get answers, while promoting the advantages of agile vis-a-vis the transparency it brings

Management of Project Stakeholders

The adoption of agile required the Kid Power team to create a new interface for the rest of the organization, as already described.

Additionally, the evolution of the program required the Kid Power team to shift from managing a few institutional stakeholders (e.g., the Mayor's office, the city Department of Education) to thousands of individual educators. This shift from B2B to B2C was made possible by the establishment of new key performance indicators which measured the engagement and onboarding of individual teachers—for example, the percentage of teachers opting in for SMS communication (since email was not a reliable channel for time-sensitive communications such as behavioral nudges to encourage teachers), the percentage of teachers having fully registered their students with Kid Power Bands and accounts within 72 hours of receiving their Kid Power classroom kit (which represented the ease with which Kid Power technology could be set up by a teacher, and resulted in a series of logistics and communications changes, which significantly improved teachers' onboarding experience).

Use of Social Media

The evolution of the program from B2B to B2C required a focused outreach and communication effort to reach educators directly, which was accomplished through a combination of email, social media, and SMS and leveraged user-generated content from teachers already participating in Kid Power. The dedicated effort to nurture and support a community of teachers via social channels not only generated compelling content, but also drove a massive increase in demand for the program.

Use of Collaborative Techniques

The success of the program was, in part, the result of engagement of teachers in every aspect of the program, from focus groups to inform design choices, to livestreaming training sessions hosted by teachers who loved Kid Power, to recruitment of teachers with massive social media followings to be Kid Power spokespeople.

The Business Model

Shifting from a B2B to B2C approach to engaging and managing stakeholders applies to any industry where end users have the ability to directly adopt a product or service without requiring an institutional commitment. While this approach has been taken by a new breed of enterprise software companies who use freemium services to attract early adopters among employees, the Kid Power team has proven this approach can work with offerings that include physical goods as well, which unlike software, is applicable to almost every B2B industry.

Globalization

The Kid Power team consisted of employees who worked across four states in the United States, contractors in the United States, Ukraine, Pakistan, and China, agencies with team members in the United States and Europe, and a manufacturer in China.

Agile, with its rigorous upfront planning and clear definition of tasks and deliverables, is well suited for work executed by distributed teams. Additionally, all internal communications were shifted to Slack, which is a fantastic tool for real-time collaboration, and all live interactions defaulted to video, which promoted more personal interactions (than audio calls). Finally, cycle planning sessions alternated between all-remote (which ensured that the design and structure of those planning sessions worked for remote participants vs being biased toward co-located participants) and all in-person (which allowed team members to build relationships and trust).

Stakeholder Support

The organization's board, while initially cautious of Kid Power, has also embraced the program. In 2016, every board member made a contribution to Kid Power, the first time 100 percent of the board has contributed to a single program.

The organization's management team, while similarly cautious, has embraced the program. In early 2017, the organization's new five-year strategic plan included Kid Power as the primary vehicle for engaging American families in UNICEF's mission.

Achieving Strategic Objectives

Educators have embraced Kid Power as a highly effective program for their classrooms. Based on teacher surveys conducted in 2016 and 2017:

- 95 percent of teachers participating in Kid Power want to participate in the program again

- 95 percent of teachers participating in Kid Power would recommend the program to their peers

Additionally, demand for Kid Power among educators has grown tremendously:

- In 2015, Kid Power received applications from teachers representing 80,000 students in 60 days, at an expense of $1.14/student in marketing and recruiting costs.

- In 2017, Kid Power received applications from teachers representing over 200,000 students in 28 days, with $0 marketing and recruiting costs.

Conclusion

Innovation is not restricted to just the private sector. Innovation can also exist for humanitarian purposes and to benefit the world population as a whole.

INNOVATION IN ACTION: SAMSUNG

Some companies focus heavily upon creating new products and hoping for the best, regardless of the value that the customers may see in the product. Samsung recognized that there is a significant difference between introducing a few new innovative products occasionally and becoming a global innovation leader. The main difference, as Samsung has identified is focusing on value innovation.

Background

Samsung and other companies have adopted a value innovation approach, as discussed in Chapter 2, which allowed them to create a corporate culture for becoming an innovation leader rather than an innovation copier and follower. Some characteristics of Samsung's culture includes:

- Innovation-oriented sponsorship and governance from the top of the organizational hierarchy downward

- Line of sight about the executives' vision and the company's strategy and strategic objectives for all employees to see

- Use of open innovation practices as well as seeking out innovation ideas internally

- Establishing strategy and innovation centers as well as open innovation centers for better knowledge management

- Recognizing that knowledge management supports core competencies for storage and reuse of knowledge from R&D activities

- Recognizing that globalization in a turbulent environment requires nontraditional systems

- Maintaining customer-focused product innovations

- A willingness to accept innovation risk-taking

- Flattening of the organizational hierarchy

- Development of speed-focused innovation strategies and execution

- Decisions are being made quicker than before

- A reduction in cycle time from months and years to weeks

- Low-cost manufacturing

Conclusion

These characteristics have allowed Samsung to develop superior core competencies. The results of Samsung's value-driven culture have led to innovations in products, technology, marketing, cost reduction, and global management.3

AGILE INNOVATION IN ACTION: INTEGRATED COMPUTER SOLUTIONS, INC.

Background

The challenges we face today, and the ones we will be facing in the coming months and years, are due to the exponential pace of technological change that is rapidly transforming our societies and competitive landscapes. As someone that has been involved in the practice and management of technology innovation for over 30 years, I have seen the pace of technological change increase from the steady linear growth in the 1980s to the exponential acceleration in the 2000s, to today's nearly vertical pitch where major open-sourced breakthroughs are compounding each new weekly advance, leading to new products and services and even entirely new markets at a clip that is difficult to comprehend. To ensure their continued existence with the hope of remaining competitive, successful organizations are changing their approach to innovation management to include Agile concepts. Those that desire to shape the pace of change to their advantage are going further, implementing the holistic “Agile Innovation Master Plan”—a framework created by world-renowned author and innovation thought-leader Langdon Morris of InnovationLabs—which was designed to provide a comprehensive yet extremely Agile approach to managing innovation strategy, portfolio, process, culture, and infrastructure. It is my belief that implementing the Agile Innovation Master Plan is not only a good idea for innovative organizations —it may be the only way to ensure their survival.

Five Key Tracks

The Five Key Tracks (Morris 2017, 12), as defined in the Agile Innovation Master Plan, are derived from five simple questions: Why innovate? What to innovate? How to innovate? Who innovates? Where? Answering these simple questions reveals the foundational framework components related to strategy, portfolio, process, culture, and infrastructure, and it is these five components that are utilized in the creation and implementation of a “system for innovation.” Langdon Morris captures the importance:

To innovate consistently, you have to make a distinction between luck and innovation. Either you have a reliable system for innovation that delivers consistent results, or you hope that your people luck into good ideas. Those are the only two options. Which do you prefer?

Since you are reading this, it likely means you desire such a system for your organization. However, it is important to keep in mind that we are discussing a framework for innovation success and understanding the importance of each track —and how the tracks feed and inform each other—is paramount. How you implement each track may be quite different than our experience, but the order of implementation of each track was crucial for our success. The first step, however, is understanding the Agile innovation sprint.

The Agile Innovation Sprint

The Agile innovation sprint uses complex thinking, design thinking, and other creative efforts in an iterative sequence of six stages for the implementation of The Agile Innovation Master Plan. The intriguing aspect of this approach is that the same methods you will use for your innovation process are utilized for its implementation, which results in an acceleration of learning in preparation for your innovation efforts. Similar to Agile software development, where small features are immediately usable as they are implemented, the agile innovation sprints produce usable features and capabilities that further accelerate implementation. In other words, the more tracks you implement, the faster you implement subsequent tracks, while gaining mastery of important concepts and methodologies along the way such that when all five key tracks are complete, you will already have a high level of efficiency in your innovation program. The diagram in Figure 12-2 highlights the general concept. The stages are understanding, divergent thinking, convergent thinking, simulation and prototyping, validation and the innospective. These stages serve to break down the design and implementation of each track into smaller pieces that—when complete—are functionally usable in your innovation efforts.

Figure 12–2. Agile Innovation Sprint.

Part 1. Understanding the Five Parts

You will note that the order of importance of the five key tracks is quite different in terms of understanding them than it is for implementing them (at least it was for us), and the reason for this is quite simple: You must be organizationally prepared to achieve success in your innovation program, and one key prerequisite is having a common language of innovation. This is shown in Figure 12-3.

Figure 12–3. The order of Understanding and the Order of Implementation.

The point being made is that once understanding is achieved, the implementation—which begins with building a culture that supports innovation— becomes much more likely to achieve success as everyone will be swimming in the same direction. Of course, learning is what innovation is all about, but the goal is to let you learn from the lessons we learned after our time spent in discovery, development and testing of this framework during our implementation. By following this approach, you will be able to accelerate your learning curve across your organization, rapidly moving up the levels of the pyramid of mastery” (Morris 2017, p. 320) (Figure 12-4).

Figure 12–4. The Pyramid of Mastery Denoting Efforts and Maturity Levels

It is important to note that our company did not start from scratch: Our CEO understood both the need and the value of innovation for years prior to my arrival, and in fact led efforts that achieved some tangible benefits for both ICS and our customers. However, without a system in place, there was no means of ensuring consistent outcomes. Some of the infrastructure was there along with some creative geniuses, but they were lacking just about everything else: an organizational culture to support innovation, a link between strategy and innovation intent, an innovation leader and innovation “champions”, and a rigorous process that could produce results in a repeatable, consistent manner. In other words, like so many companies that have a desire—but no system—it is easy to get stuck at lower maturity level. As we implemented our own Agile Innovation Master Plan, we rapidly moved from maturity level 2 to a mastery level in less than a year—and it all started with understanding—a word you will hear repeatedly due to its importance as the first stage in the Agile innovation sprint (Morris 2017, 128).

Understanding the Strategy Track

Most successful organizations will have strategic objectives that support their raison d'être—their purpose or reason for their existence—and it is the link (Morris 2017, 25) between strategy and innovation that determines your organization's ability to achieve its objectives while continuously adapting to the frenetic pace of societal and technological change and the resulting uncertainties they introduce (Morris 2018).

Whether you are innovating on behalf of your organization or on behalf of your customers (or both, as is the case for our organization), understanding why you are innovating (strategic intent) is necessary before you can determine what to innovate (portfolio) to achieve the desired outcomes. In effect, aligning ideas for innovation to at least one (or more) of your strategic objectives is a risk and opportunity mitigation strategy: If you focus only on ideas that are aligned with your strategic intent, you will not waste your efforts on ineffective expenditure of time and resources.

Each of the strategic objectives of your organization (or your customer's objectives, if innovating on their behalf) will likely have a weighting—and if they don't, they should. In other words, some strategic objectives will be more important than others. For example, one of our DoD customers lists four strategic objectives on its website. One of them—optimize and reduce costs—will certainly have a higher priority (or weighting) in peacetime than during a time of war (where cost optimization is less of a concern due to mission requirements). Conversely, it may have an even higher weighting than normal if budget constraints are enacted. There are logical and obvious conclusions that can be drawn from this understanding:

- The strategic objectives themselves can change.

- The weightings of each objective are not necessarily equally balanced.

- The weightings can change dynamically, depending on conditions or events.

The first point will seem obvious to organizations that are mature in their approach to innovation, as the “understanding” stage of an Agile innovation sprint requires that management frequently reconsider changes in the technology landscape, competitive landscape, market conditions, and tacit (or hidden) customer needs, which are necessary to remove uncertainty about the strategic direction of the organization and which can result in changes to the strategic objectives in response. This is a logical outflow of the “unpacking” of conditions that identify pain points, problem statements, and trends and opportunities to be addressed by the organization (Morris 2017, 176). However, all of the above considerations have an extremely important role to play in balancing your innovation portfolio and they underscore the importance of agility in adapting to the pace of change.

While your organization may already be structured to do so with its strategic objectives, it is imperative that your innovation portfolio management capabilities be designed such that the entire innovation portfolio can be realigned—or “pivoted”—any time the portfolio evaluation factors and/or their weightings change, to be sure that your innovation efforts remain in direct support of current strategic objectives and weightings.

Understanding the Portfolio Track

A properly balanced innovation portfolio helps an organization align its innovation efforts with its strategic objectives while balancing risk. The kind of risk to be balanced can come in many forms—one such example being in terms of time—over the near, medium, and long-term according to the types of innovation being pursued. Fundamentally it is a strategy for managing risk such that the entire portfolio as a whole can achieve a desired return even when an individual project fails (and they will, or you aren't taking enough risk to explore the world of potentials, nor are you likely learning anything new).

In this section, both ideas and projects are referenced. However, there are times when you can treat the portfolio of ideas separately from the portfolio of active projects, and times when they need to be treated together. These are important considerations when you get to the implementation phase, but for our purposes, here the important part is understanding that there can be a distinction between the two.

There are a variety of methods to balance a portfolio and maintain an acceptable risk profile:

- Scoring each idea or project's orientation toward the strategic objective weightings

- Scoring each idea or project according to the type of innovation it represents, such as incremental, business model, breakthrough, or new venture

- Scoring each idea or project using risk and/or reward factors aligned to your strategic intent

- If technology-related, scoring the idea or project by its technology classification such as AI, Machine Learning, Cloud, etc., depending on strategic focus in each area

- Any combination of methods

One of the standard methods referenced in the Agile Innovation Master Plan is a risk/reward evaluation, which is a very useful method that can apply to any organization. Consider the following example reward factors:

- Benefit to customers

- Revenue potential

- Competitive advantage

- Enhances our digital presence

- Enhances our brand

Similar to strategic objective weightings, the desired reward factors (or opportunity factors) can be assigned a weighting by management (a level of strategic importance on a scale of values), and then each idea or project can be rated for closeness of fit (again, on a scale) by interested parties4 at the time of its introduction. On the opposite end, risk factors (financial risk, technology risk, market risk, or other risks recognized by your organization) can be managed in an identical manner: Weightings are applied by management, and individual ideas or projects can be rated for closeness of fit.

Using a simple form as shown in the following example, illustrated in Figure 12-5, both cumulative reward and cumulative risk factors can be generated.

Figure 12–5. Example Risk/Reward Evaluation.

In this example, the “fixed”5 weights for each reward factor (assigned by management) are multiplied by their associated rating, and the products for all reward factors are summed to obtain a cumulative reward score.

The weights for each risk factor (again, assigned by management6) are multiplied by their associated rating, and the products for all risk factors are summed to obtain a cumulative risk score.

Together, these scores can be used in a data visualization exercise to align ideas or projects on a risk/reward matrix. In the matrix shown in Figure 12-6, the “Target Zone” reflects the region with the optimal balance between the computed risk and reward factors (lowest risk and highest reward.)

Figure 12–6. Risk/Reward Matrix.

With a scale factor applied to the axes, it is possible to visualize each scored idea or project in comparison to all others, such as in the Risk/Reward Matrix shown in Figure 12-6.

Note that this approach even allows for investment thresholds to help determine the dividing line for inclusion in the active portfolio.

As mentioned in the prior section on strategy, it was noted that the strategic objectives and their weightings can change due to conditions or events. The same is true for risk and reward factors and their weightings if using that approach. If the appetite for a particular type of risk is changed by management, it could impact the evaluation of every active project (as they may no longer be in alignment.) The same is also true for ideas—whether in the active portfolio or not —as they may not have “made the cut” the last time but may this time under different evaluation criteria.

When evaluation criteria change, all ideas and projects that could be impacted must be evaluated under the new conditions. See Figure 12-7. Also, if an evaluation factor is added or removed, all ideas or projects must first be rerated and then reevaluated to ensure that the portfolio of ideas or projects are in alignment with current strategic objectives and priorities. In these scenarios, active projects can be abandoned, deferred, or even killed.

Figure 12–7. The Ideal Risk/Reward Portfolio.

Conclusion

Agile Portfolio Management is the most important aspect of your innovation management practice. You may have great ideas aligned with strategic intent, a culture to support innovation and a rigorous process with the proper infrastructure and tools to develop and implement them, but unless your innovation outcomes are in alignment with your organization's current strategic intent you won't be exploiting the right opportunities.

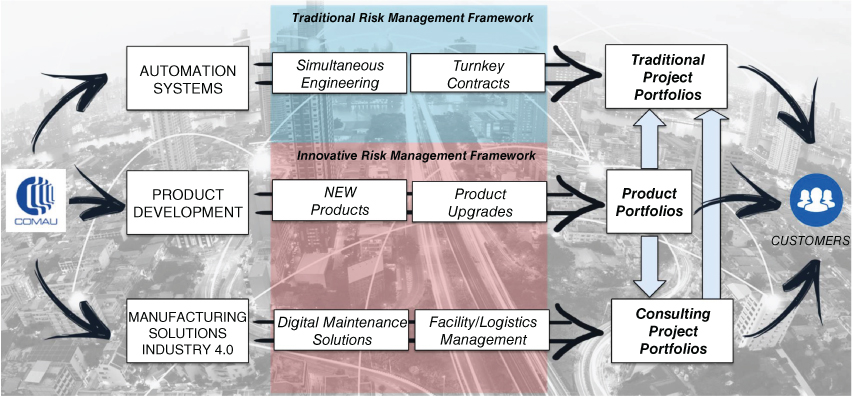

INNOVATION IN ACTION: COMAU

Introduction

COMAU is a worldwide leader in the manufacture of flexible, automatic systems and integrating products, processes and services that increase efficiency while lowering overall costs. With an international network that spans 15 countries, COMAU uses the latest technology and processes to deliver advanced turnkey systems and consistently exceed the expectations of its customers. COMAU specializes in body welding, powertrain machining and assembly, robotics and maintenance as well as environmental services for a wide range of industrial sectors. The continuous expansion and improvement of its product range enables COMAU to guarantee customized assistance at all phases of a project—from design, implementation and installation, to production start-up and maintenance services.

COMAU innovation is based on manufacturing's digital transformation, added-value manufacturing and human-robot collaboration; these key pillars allow COMAU to reach new heights in leading the culture of automation.

The COMAU Project Management Office (PMO)

In 2007, COMAU established a contract and project management corporate function, with the aim to create a stronger link between leading roles and project management and to ensure coherence between execution and company strategy. Over time, the contract and project management function grew in responsibility (as shown in Figure 12-8) and modified its structure to reach a configuration based on the coordinated sharing of knowledge and activities between PMO, risk management office and the COMAU PM Academy. The fourth pillar that sustains COMAU Project Management framework is constituted by the PMI® standard set, recognized as the best practice standard in the Project and Portfolio Management landscape.

Figure 12–8. COMAU Contract and Project Management Office.

PMO Innovation Pillars

In recent years, COMAU started thinking about the industry in a new way, developing new scenarios, designing innovative products, creating ways to streamline production processes, and defining new trends in digital manufacturing, creating a new paradigm to balance collaboration between people and machines.

We call it HUMANufacturing, the innovative COMAU vision that places mankind at the center of business processes within a manufacturing plant, in full cooperation with the industrial automation solutions and new digital technologies that surround them. The above vision needed changes and innovation in all company organization roles to be sustained.

The COMAU PMO is therefore innovating, expanding its project management landscape from traditional industrial project portfolio to new forms of projects, such as new product development, digitalization, and industry4.0 projects.

Through the innovation in each of the five pillars (see Figure 12-9) the PMO is now positioned within the organization as a valuable business partner, one that sharpened its capacity to be adaptive for different forms of projects within the company.

Figure 12–9. COMAU PMO Innovation Pillars.

1. Leaner Execution Processes

Scenario Analysis The current context of market evolution highlights new disrupting influences:

- The degree of innovation is becoming predominant in all COMAU projects

- The size of traditional EPC projects is continuously decreasing

- The development of new, innovative, digital products and solutions is more and more expected by our customer base (traditional automotive, and new customer base: new automotive, general industry, electric vehicle)

Consequently, COMAU began a deep analysis of the current project execution course of action (process, organization, and tools) and of the project management methodologies adopted, to verify the alignment to market needs.

COMAU redesigned its project management process to make it scalable to the degree of innovation typical of each project and adopting where applicable Lean and Agile solutions.

Guidelines The main guidelines followed:

- Profile the process based on project classification criteria. From the well-established COMAU PM process, optimization is achieved by selecting the appropriate activities/tasks/milestones that fit each different project, maximizing the business added-value.

- Empower project managers and encourage team co-location to improve the integration and communication within the team members, and of the project team itself with functions and finally with the customer.

- Team co-location has introduced a work space re-layout, the integration of the planning activities, and the introduction of a platform organization.

- Digitalization of the project management process, realizing a paperless process in order to achieve a faster and more user-friendly utilization and optimize time/cost of process management.

- Encourage visual management, and exploit the potential of mobile applications (see Figure 12-10)

Figure 12–10. COMAU Project Management Digital Process & New Tools (i.e., Agile Visual Management).

The benefits obtained with these operations have been a reduced complexity, reduced time and lower effort for milestones and activities/tasks execution and, in general the reduction of “not value added” operations, maximizing effectiveness and efficiency as requested by the current business scenario.

2. New Project Management Framework for Product Development

The product development business of COMAU is broad, as the company has many branches that require different technologies and competencies. All have very diverse needs when it comes to product development projects, while at present the company only provides the business units with one project framework that supposedly should fit all their needs.

How is it possible to merge the need for differentiation among the businesses with the struggle to keep uniformity within the company? The answer to this question is in having one single process for product development projects that is modified case by case. To achieve this result, it is important to understand how to characterize each project in order to have the elements needed to customize the process. The main elements to be taken in account are product development complexity and innovation; the frame proposed to assess product complexity level is as per the matrix shown in Figure 12-11.

Figure 12–11. The Company Matrix.

This matrix is just a part of a wider evaluation tool that guides the user in the definition of the project needs. Other focal points are:

- Field competences

- Sales outlook

- Project risks

- Product strategic relevance

According to the differentiation derived from this evaluation tool, we can then identify and apply different project management patterns. These patterns are identified by selecting the right steps among the ones available in the company process. In this way it is possible to assure the highest quality is delivered while consistently reducing the effort every development team has to put in place in order to act accordingly to the company standards and frameworks.

COMAU encourages the use of a mixed approach that merges stagegate and Agile project management principles. Exploitation of Agile tools and methodologies enables shorter development time, with a consequent cost reduction, and an improved target achievement as the whole team is more focused on the value to be generated and on the customer needs rather than on following a rigid internal protocol.

3. COMAU Risk Management

History and Achievement In 2006, COMAU began to address risk management with a more focused, strategic approach, recognizing it as an essential part of the successful completion of projects. With the increase of organizational complexity and global presence it was necessary to find more structured and refined tools for managing uncertainties. Consequently, in 2010, a risk management office as part of the PMO was created (see Figure 12-12).

Figure 12–12. Risk Management within the COMAU PMO Framework.

Specific responsibilities of the risk management office included the definition of a framework (methods, processes, tools) for the management of projects and portfolio risks as well as improve the concrete application throughout the entire project life cycle.

Beginning in 2015, COMAU decided to make a further maturity step, launching an initiative aimed to reinforce and better integrate risk management practices at different company levels (contract sales, project execution, and portfolio management) with a global perspective (see Figure 12-13).

Figure 12–13. The COMAU Risk Management Initiative

The completion of the initiative provided COMAU with the adequate risk management approach and tools needed to manage the turnkey projects portfolio composed by fixed-price EPC contracts, each characterized by a high degree of complexity and a fixed scope for which a traditional project management predictive approach is to be adopted.

Risk Management for Innovative Projects. The acceleration impressed by the digitalization era required changes to business model for many companies included COMAU. Risk management as all other functions within companies is required to change as well and to approach new models to cover new forms of projects, those that might be named innovation projects (see Figure 12-14).

Figure 12–14. New frontiers for Risk Management.

Innovation projects such as new product or solution development and digitalization projects have peculiarities that need new risk management approaches. To fit with this requirement, COMAU developed a first “concept” to extend and integrate the well-established traditional risk management.

The concept is based on the following guidelines:

- Risk management is a primary vehicle to reinforce PM “strategic thinking” into project execution.

- New risk management approach might bridge the project management perspective from tactic to strategic as it focuses on pursuing a wider business-value objective.

- Project managers are now expected to master company business processes in addition to the PM process and to be than able to anticipate the implications of project decisions on the different functional objectives, communicate them, and collaborate with functions to set up counteractions.

- New company functions and customers are involved in project risk management.

- Accepting that perimeter of project risk management is widening, there are a number of people/structures within the company (i.e., innovation, marketing, sales functions) that become important stakeholders, bearers of interests and objectives that, differently from the past, might be subjected to redefinition while the project is ongoing (Agile approach).

- New metrics to measure project risks.

- The value expected and created by innovation projects goes beyond the end of the project itself. The project constraints to be taken into account when assessing the risks are not only limited to scope-time-costs as in a traditional predictive approach. New metrics for the qualitative and quantitative analysis of risks that could include also a wider, more strategic measure of long-term risk impacts are needed. COMAU's new approach to project risk management, as seen in Figure 12-15, is therefore based on a hybrid of predictive and adaptive components.

Figure 12–15. NEW metrics for Risk Management (PROUCT DEVELOPMENT EXAMPLE)

4. COMAU PM Academy

Developing Innovation Project Managers The PM Academy in COMAU is responsible to ensure people involved in projects are technically skilled and behaviorally prepared to participate in and manage projects. In front of the need of innovation PM Academy challenge is to support project manager transformation in the company—from a person strongly plan and process oriented to a person more and more aware of its strategic role in the creation of value for the company. And what do we need to reach it? Essentially a project manager must be very flexible, culturally sensitive, political-driven, business-oriented, and a master in communication and leadership.

In this new context PM Academy continues its efforts to provide valuable international project management best practices and support the certification process; but this is integrated with Agile and Lean concepts and methodologies, and enriched leadership models.