CHAPTER 5

Designing the Investment Management Process

Key Take Aways

The investment management process is the process by which the pension fund intends to achieve its investment objectives, which follow from the fund's mission. Over the longer term, pension funds aim to generate at least the net returns needed to realize the pension's promise, often within a certain risk budget. Often, there is a distinction between a hard, nominal liability and an often less hard ambition to index the liability with price- or wage-inflation. Four key ingredients tend to drive investment decision-making1: matching assets and liabilities, generating investment returns over and above the matching return, risk management through portfolio diversification, and cost management. The way in which these ingredients are combined can be called the investment process.

This process varies greatly in shape and size. Two funds that seem similar from the outside might generate different investments returns from the inside. However, despite investment processes differing widely, they all have a number of specific building blocks in common. The process can be viewed as an implementation of the objectives, the investment beliefs, and the governance budget of the fund. There will almost always be constraints, for example on the maximum amount of risk or regarding unacceptable outcomes.

For a trustee, it is important to understand these building blocks, how they work together, and what the underlying assumptions are. It helps to understand how the returns are being made, what investment governance is needed for this (Chapter 6), and how to manage and nurture the success factors in day-to-day operations (Chapters 7–9).

This chapter describes the main steps of the investment management process. The portfolio management process starts with planning, then goes to execution, and finally to feedback. The next part of this chapter gives an overview of the portfolio management process. We then delve deeper into the main decisions of the investment process, namely setting the objectives, formulating the capital market expectations (CMEs), and portfolio construction. Next, implementation and monitoring are considered. The chapter ends with a discussion about the document that helps the board focus and streamline the important choices in the investment process: the Investment Policy Statement (IPS).

At the planning stage, investment objectives and policies are formulated, CMEs are set out and, often, a strategic asset allocation or policy as well as a risk budget are established. At the execution stage, the portfolio manager actually constructs and implements the portfolio. In the feedback stage, the output is reported, monitored, and evaluated by means of comparison to the plan. The feedback can lead to changes in objectives, portfolio or process. There will be a heavy involvement from the board during the planning process and the feedback loop; conversely, the execution will be in the hands of the investment management organization. The level of delegation and the way in which the board specifies the investment objective and mandate to the investment manager vary widely among different investment models, for example as seen in the Canadian (extensive delegation) and the Dutch (little delegation) models.

THE INVESTMENT PROCESS

There are three reasons why trustees should have a well-thought-out investment process:2 (i) it describes all the necessary steps between the goals and realizing actual returns to achieve those goals; (ii) it makes the assumptions behind these steps clear, allowing them to be challenged and improved; and (iii) it provides the board with insights about which choices do and do not work, helping it to evaluate effectiveness and adapt or change elements where necessary. Let us now further expand on these points.

Point 1. The investment process describes the steps between the clients' objectives and the delivery of investment returns to achieve them. These steps are taken in a specific order and form the main choices that are made. These steps will usually include the formulation of investment objectives, the forming of expectations or assumptions about the future returns and risks in the financial markets, strategic asset allocation, a number of mandates for different asset classes or parts of the portfolio, tactical/dynamic asset allocation, rebalancing and risk management. Risk management is embedded throughout the process to provide the necessary scope for rewarded investment risks, and to avoid, mitigate or sell off additional risks that arise when the asset transformation takes place, and where the investment organization does not expect to be rewarded.

Point 2. The investment process also helps to clarify and challenge the assumptions and beliefs behind all of these choices and provide an argument as to why the board makes particular choices out of the many types of strategies that are available. The choices depend to a large extent on the investment beliefs of the fund (Chapter 4).

Some steps in the investment process are more important than others. For example, the strategic asset allocation is considered to be much more important than tactical asset allocation or implementation choices such as the hire of specific managers for mandates.

Making the assumptions clear, and assessing what the expected contribution of each of the components is in relation to the whole helps a board to deal with the question of information asymmetry: investment managers tend to know more about financial markets and their processes than trustees, and might consciously or unconsciously promote strategies and assets that are in the best interests of the investment managers rather than the fund. A board that knows the assumptions behind the different steps, knows the degree of confidence and the evidence that can be attached to these, and is able to make a more informed decision as to whether such a strategy contributes to meeting the fund's goals.

Point 3. The process provides the pension fund with a learning perspective, giving insights into which steps work and which don't. Investment processes are not static. Financial markets and their participants are adaptive in nature because they continuously interact, learn, and react. What today constitutes a good investment strategy or asset class might be less suited for portfolio construction in five years' time. A decision may have been good at the time it was made, but circumstances could have changed in the meantime, in which case the board should adapt accordingly. It is not easy to decide which decisions hold up for a relatively long time, compared to others that have a shorter life span. Here, the feedback loop plays an important role. When information about the realized results is channeled back to the board and its committees, it provides feedback about the choices that were made, which enables self-correction if limits or boundaries have been breached. It also allows for the learning and adjustment of the investment management process if this can improve potential outcomes. The investment process is visualized in Exhibit 5.1.

EXHIBIT 5.1 The investment management process.

SETTING OBJECTIVES: ALIGNING GOALS AND RISK APPETITE

The process begins with the aims that follow from the pension scheme. How can these be translated into financial goals and how much risk can and should be taken in order to achieve them? These goals and restrictions for both the short and long-term for return and risk are then translated into a set of inputs for the portfolio decision process.

The investment objectives and risk appetite must be decided on by the board. The starting point for this is developing the returns objectives, and the investment risk participants can and are willing to incur in achieving investment goals. However, determining risk appetite is not the only risk factor that must be taken into account. One must also ask whether the pension fund can afford to incur the investment risk? Or, can it afford not take the investment risk? Taking on the appropriate amount of risk on behalf of the participants and subsequent management of risk is a key success factor for pension funds, but it is also a balancing act between short and long-term trade-offs. Taking on risk, for example by increasing the allocation to equities, might on the one hand earn the pension fund a decent return for its participants. But on the other hand, it exposes the pension fund to the risk of the financial markets, which might in the short term hamper progress towards its long-term return goals. In other words, the risk profile not only specifies the amount of investment risk the fund will take in pursuit of its goals, but also describes how the amount of risk varies in different economic circumstances or with the financial health of the pension fund, as well as the trade-off between short-term and long-term risk. These choices are deeply influenced by the availability of a strong sponsor, the maturity of the fund, and the nature of the liabilities.

The risk profile can be (and usually is) established in a quantitative way. Many investment committees are involved in carrying out the asset liability management study. The justification of quantitative assumptions, the choice of (deterministic) scenarios and risk benchmarks, and the creation of asset allocations are the important elements in this context, and committee members will have a controlling role to ensure the assumptions and outcomes are acceptable. A board of trustees has to consider more than just stakeholders, and more than solely financial aspects. A risk profile is therefore quite broad, consisting of three dimensions. First, the financial dimension addresses how much financial risk is needed and how much the fund can absorb. Then, the participants' dimension takes a broader view than just financial risk and determines whether the risk profile fits the characteristics of the participants. Finally, the pension fund's perspective looks at whether the organization is able, permitted and equipped to take on the amount of risk determined by the financial and participant perspectives. These risk profile dimensions are presented in Exhibit 5.2.3

EXHIBIT 5.2 Common denominators in the amount of risk.

For each of the three dimensions, the board has to consider the following elements:

Financial perspective:

- Clarity on who accepts how much of the investment risk, as a consequence of the pension plan. This involves identifying and quantifying investment risk shock absorbers, which potentially are elements such as buffers, premium, sponsors, and a long horizon. As a rule of thumb, the fewer shock absorbers are available, the lower the investment risk that can be taken or the more the promise will have to be flexible;

- The degree of financial health, measured by cover ratio or solvency. A higher cover ratio provides a buffer and, therefore, more scope to take risks than a lower cover ratio. The board has to consider different levels of cover ratios; would the fund take the same amount of investment risk regardless of the cover ratio? For example, if the cover ratio increases, this could mean investment risk can be reduced. This provides the framework for a dynamic risk appetite statement;

- The premium. The actual premium can be higher/lower than the purely cost-covering premium, meaning that more/less risk can be taken. In young funds with a relatively high premium flowing in, the premium can be a strong steering instrument. However, currently funds around the world are maturing rapidly and premiums are already high, which makes this an instrument of limited value;

- The sponsor. A strong sponsor standing behind a fund, such as a state or a strong company, can help to absorb shocks. An example is Royal Dutch Shell, which injected money into the Shell Pension Fund after the great financial crisis.

Participant perspective:

- The pension fund life-phases. A young fund requires a longer period to recover from financial setbacks and can take greater risks than a fund that is already in the payment phase and has fewer active participants;

- Participants' profile. How flexibly can participants accommodate any mishaps in terms of pension payment within their private situation? For example, a pension fund for poorly educated, low-wage employees cannot assume that participants have any supplementary wealth and can, after retiring, use other assets to ensure the desired income.

Pension fund organization perspective:

- The desires of social partners. The aims of the pension scheme are set out when employment conditions are under discussion. The degree of certainty that is required leads to a specific level of risk;

- Laws and regulations. The risk profile must “fit” within the existing regulatory framework, and the “prudent person” rule. It should not be aimed at “arbitraging” away regulation;

- The exclusion of assets, socially responsible investment, and guidelines in consultation with the sponsor, such as their business principles for example;

- The board. A board with more expertise and experience can (but does not necessarily have to) take more complex risks than a board with less experience and expertise;

- The level of risk preparedness of the board. The board and board members are personally liable for the fund policy. The board may therefore wish to bear lower risks than are (theoretically) possible as a result.

The role of the board in determining and maintaining the risk appetite cannot be underestimated. “While risk management is the […] first priority, this most definitely does not mean overly conservative “caution.”4 In this setting, alongside monitoring and managing short-term risks, the board must also avoid unnecessary long-term risks by on the one hand tempering the risk appetite in good periods, and on the other hand avoiding opportunity loss by sustaining the risk appetite in periods when risk aversion increases.

Developing a detailed risk profile is becoming more common among funds, but it is not easy for boards to do. An important reason for detailing the risk profile is that it not only disciplines trustees with respect to the risk to be taken, but it also helps them discipline the board in this area.

There are two points at which boards can cause problems for the achievement of the fund's aims.5 The first is when it is excessively cautious, for example after a period of falling coverage and increasing volatility in financial markets. Capital retention then has precedence. The greater the impact on the pension fund, the longer the risk aversion and caution will be maintained; this may result in the long-term aims not being realized. The second point is that the opposite is also true. A pension fund can build up a large risk appetite and assume greater risks than are really necessary in order to achieve the fund aims. This mainly occurs during periods of expanding markets in which excessive optimism prevails. Developing a disciplined decision-making process to operate within the risk profile is therefore a key element for long-term success. This will be discussed in Chapter 12, in which we explore the dynamics at play between the board and the investment committee, and decision-making under stress.

Investment Objectives

Four groups of investment goals appear during the formulation of the return objectives, where the relevant question for the board is which group or combination best reflects its investment goals. These goals are as follows:

- Absolute return (or inflation + a specified absolute return). The fund aims at a specific percentage investment return, regardless of the liabilities. This goal is suitable for pension funds with a relatively low degree of liabilities or undetermined liabilities such as sovereign wealth funds, or those with a financially strong sponsor who will vouch for pension payments and step in the potential event of pension payout deficits;

- Investment return derived from the stream of benefits it has to pay. The fund aims for the continuation of the payments with a specific probability;

- Investment return on the surplus (also known as liability adjusted returns). The fund actively manages the surplus of the pension fund. The assumption here is that part of the assets is designated to match the liabilities and is therefore constrained. Assets and liabilities are managed on the same balance sheet, and are not physically separated. This goal is suitable for pension funds with high liabilities, where compensation of the accrual of liabilities becomes an important part of the objectives;

- Separate investment returns for the liabilities and the surplus. Liabilities and surplus are managed separately, such that the investment portfolio for the liabilities matches these liabilities, while the surplus portfolio has to generate returns. The board can define a set of rules under which part of the surplus is transferred to the liabilities portfolio, or could leave this decision to the participants, who invest in the liabilities and surplus portfolios. For example, if the surplus of the fund reaches more than 10%, then a certain percentage is transferred to the liabilities portfolio.

Whichever combination of objectives is chosen, the board must also set the horizon in which the goals apply, and determine the rules for evaluation beforehand. If an absolute return averaging 6% has not been met over a five-year period, how should this be evaluated?

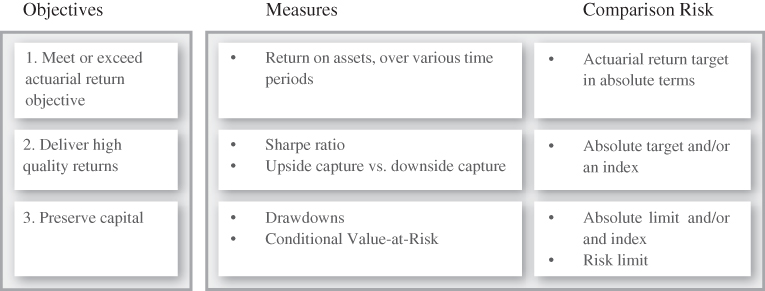

Pension funds usually run a scheme based on a matrix of objectives that combine return and risk measures: the actuarial return should be met or exceeded for the overall portfolio; within the portfolio, the risk-adjusted returns should be above a certain threshold, and when the fund actively aims for the preservation of capital, there are risk limits to protect the liabilities. Exhibit 5.3 presents an example from the pension fund of CERN (the European Organization for Nuclear Research).

EXHIBIT 5.3 CERN's matrix of objectives, measures and benchmarks.6

FORMULATING EXPECTATIONS

Another input in the investment process is CMEs: expectations concerning the risk and return prospects of asset classes, and how they interact. These help to formulate a strategic asset allocation. Defining a CME requires determining short-term and long-term return and risk expectations for the major asset classes in the portfolio, expectations for important variables such as inflation and the interest rate structure, as well as for the correlation matrix for the assets.

Trustees should approve the CMEs, if only to be aware of their sensitivity and the impact that they have on the resulting portfolio and the outcomes of the investment process. The more impact they have on the outcome, the more important it is that the board understand them and consciously approve them. Usually, assumptions about interest rates, inflation, and equity returns determine 80% of the proposed asset allocation, and should thus thoroughly be discussed by the board.

As mentioned previously, CMEs are a key input in formulating a strategic asset allocation. For example, if an investor's IPS specifies and defines eight permissible asset classes, the investor will need to have formulated long-term expectations concerning those asset classes in order to develop a strategic asset allocation. The investor may also act on short-term expectations. In practice, this means that the board at least sets the risk premiums for the main asset categories in the portfolio, i.e.:

- Risk premium for bonds: expected rewards for term spread and inflation;

- Risk premium for equities;

- Risk premium for credit risk;

- Risk premium for illiquid assets, mainly real estate.

Other assumptions about risk premiums related to subcategories, investment styles, etc., should be left to the investment consultant or investment management organization. The trustees' task is not to predict future values of these assets. The investment strategist and staff are better equipped to do this. The main purpose is to achieve an optimal set of assumptions that are internally consistent and reflect all currently available information and future assumptions that might affect the investment outcomes.

However, it is downright naïve for a board to choose just one set of assumptions and build a long-term strategy around this. The board's task may not be to predict the future, but certainly its job is to be prepared for different futures and adapt to them when they emerge. A frequently used approach is for trustees to draw up several sets of assumptions and label these “scenarios.” This reflects the understanding that radically different outcomes are possible in the medium and long term, for example an inflationary or a deflationary world (Chapter 4).

PORTFOLIO CONSTRUCTION

Having explored the preferences of the investors in developing a risk profile and setting investment objectives, and having developed a set of inputs in the form of expectations of returns and risks available in the financial markets, it is time to turn to portfolio construction. The investor's return objectives, risk tolerance, and investment constraints are integrated with long-run CMEs to establish exposures to permissible asset classes. Portfolio construction produces four outcomes7 that the board needs to approve, either as separate policies or integrated into one (the strategic plan for the coming years for example): the policy portfolio or strategic asset allocation, the strategic benchmark portfolio, the benchmark choice of the asset classes, and the rebalancing policy.

The policy portfolio or strategic asset allocation is a set of portfolio weights for asset classes. It is the result of strategic asset allocation, which allows investors to choose their portfolio's long-term profile. The assumption is that this high-level portfolio captures a large degree of variation in returns. It is an essential part of portfolio construction, and reflects the acceptable risk level, and thus to a large extent determines the portfolio future performance.

The strategic benchmark portfolio represents a set of weights within the asset classes of the policy portfolio, detailing various building blocks of the asset classes, such as the key investment styles or credit portfolios with different rating classes. Each asset class comprises a broad variety of sub-asset classes. For example, sub-asset classes within equities might include large companies, smaller companies, growth funds, income funds, and global equities. Within these sub-asset classes, a manager's approach to investment analysis and security selection can differ widely. To cluster this diversity, the concept of investment style is introduced. We can define an investment style (such as an emphasis on growth stocks or value stocks) as a natural grouping of investment disciplines that has some predictive power concerning the future dispersion in returns across portfolios.8

The benchmark choice of the asset classes should reflect the desired risk/return exposure in the financial markets for the specific asset class, as well as its investment style. There are three forms of benchmark construction: market-capitalization weightings, static tilts, and factor investing:

- Market-cap-weighted index benchmarks give broad exposure to traditional asset classes. With a high degree of liquidity, transparency, and relative risk control, broad market-capital-weighted indexes can efficiently provide the weighted-average experience of owning all (or virtually all) available securities at the market-clearing price. These diversified investment pools with significant capacity are a valuable starting point for trustees. Market-cap-weighted index funds provide a central point of return and volatility because they reflect the aggregate holdings of all market participants and because within the context of Modern Portfolio Theory, it can be argued that they are optimal, providing all investors with the best possible expected risk/return combination.

- Investors may choose to take on a larger exposure to a portion of the market that they believe offers the opportunity to outperform over the long term. These decisions are often made at the sub-asset-class level. Equity tilts are often made by size, style, sector or location; and fixed income tilts are frequently based on credit quality, duration or location.

- Investors may steer their portfolios away from the global market cap because they have different risk priorities. A prime example of this is liability-driven investing, in which the priority is claims-paying ability, not return maximization. The target duration of such a bond portfolio might well differ from that of a broad market-cap-weighted bond index.

Besides formulating the strategic portfolio and determining its benchmarks, a rebalancing policy needs to be in place: a policy on how these portfolio weights are adjusted in line with the risk appetite. This policy details how the policy portfolio is to be adjusted to changes in the cover ratio or financial markets, how to adjust the assets to the weights of the strategic benchmark portfolio, and whether the rebalancing is carried out regularly or based on triggers.

At its simplest, this is a process of regularly rebalancing to constant policy weightings. For example, suppose the policy allocation calls for an initial portfolio with a 70% weighting in stocks and a 30% weighting in bonds. Then suppose the value of the stock holdings grows by 40%, while the value of the bond holdings grows by 10%. The new weighting is roughly 75% in stocks and 25% in bonds. To bring the portfolio back into compliance with the investment policy, it has to be rebalanced back to the long-term policy weights. The rebalancing decision must then take into account many execution factors, such as transaction costs and taxes. Disciplined rebalancing will have a positive impact on the attainment of investment objectives.

Rebalancing on the basis of constant policy weights represents one pole. At the other extreme, the fund could have a solvency program in place. Such a program adjusts the policy weightings depending on the amount of downside risk the fund is willing to take given the funding ratio and financial market conditions. Similarly, the solvency program could adjust the level of policy weightings depending on how close the fund is to achieving its long-term goals. Sometimes, funds allocate part of the bandwidth around policy weightings to tactical asset allocation, which involves making short-term adjustments to asset-class weights based on the expected short-term relative performance among asset classes. The assumption is that investors can avail of short-term opportunities with the aim of achieving the best performance for the portfolio, bearing in mind the defined level of risk.

At times, a portfolio's actual asset allocation may deliberately be allowed to diverge temporarily from the strategic asset allocation. For example, the asset allocation might change to reflect a pension fund's current circumstances if these are different from normal. The temporary allocation may remain in place until circumstances return to those described in the investment policy and reflected in the original strategic asset allocation. If the changed circumstances become permanent, the manager will need to update the IPS, and the temporary asset allocation plan will effectively become the new strategic asset allocation. A strategy known as tactical asset allocation also results in divergences from the strategic asset allocation. Tactical asset allocation responds to changes in short-term CMEs rather than to investor circumstances.

IMPLEMENTATION AND MONITORING

The next element of the investment process is the actual implementation, the evaluation of the results achieved, and the possible modification of choices made in the investment process if the results suggest this. Portfolio management, risk monitoring, and information provision are all carried out by the concerned organization or outside of the pension fund. This involves the creation of the actual investment portfolio and mandates for the asset managers who manage them. Moreover, it also includes due diligence (in this case, a structured method for examining the organization and the manager's investment record before a mandate is issued), and contracting and monitoring the parties that actually implement the investment policy. Implementation is the execution of investment strategies, done by selecting managers and strategies for the portfolio, and allowing managers to initiate transactions on behalf of the fund. To manage this operation, the fund should have a monitoring process in place.

Implementation

Implementation is the process of executing the strategic benchmark portfolio and rebalancing policy. Assets and investment styles are translated into investment instruments and products that are then traded on behalf of the fund. This step introduces—and exposes—trustees to a new arena of organizations and people involved in the day-to-day operations of the fund. Portfolio managers initiate portfolio decisions based on analysts' inputs, and trading desks then implement these decisions (portfolio implementation decision). After that, the portfolio is revised as investor circumstances or expectations change; thus, the execution step interacts constantly with the feedback step. The implementation of the investment management process is further discussed in Chapter 8.

Monitoring

Monitoring involves the use of feedback to manage ongoing exposure to available investment opportunities so that the fund's objectives and constraints continue to be satisfied. Different aspects are monitored by the board, as listed below:

- Monitoring a change in the pension fund and its risk profile and objectives, and whether this is implicit or explicit.

- An assessment of the economic and market input assumptions and if they still hold.

- The rebalancing of the current portfolio within the guidelines.

- An analysis to monitor if the managers who were chosen still reflect the investment styles consistent with the expected return/risk profile, investment beliefs, and other key aspects outlined in the strategic plan.

The board has to decide to whom it will delegate these monitoring questions, for example, to the investment management organization, executive staff or investment committee, and must be clear about how the monitoring process should evolve. Which choices should the board make, and what elements are best left to the other bodies of the pension fund? For trustees, it is important that monitoring signals any potential negative side effects that can be avoided or mitigated. For example, monitoring signals cover the total amount of costs, the utilization of the risk budget, and the level of transparency in the accountability of the different steps in the implementation process.

Portfolio evaluation may also be conducted with respect to specific risk models, such as multifactor models, which seek to explain asset returns in terms of exposure to a set of risk factors. Considering that monitoring is a vital part of the investment management process, this topic is more elaborately discussed in Chapter 9.

The backbone for monitoring and evaluation is provided by performance evaluation. Performance evaluation analyzes the portfolio's results in the context of the investment management process.9 It answers the following questions: how was performance, how was excess performance realized, and what does it tell us about the added value of our decisions? Performance attribution decomposes returns into all the components that are consistent with the steps in the decision-making process. Performance attribution explains the active choices that made the portfolio overperform (or underperform) its benchmark. For example, what other assets or securities could the portfolio have held in order to obtain a better return? Was the portfolio tilted too far towards a specific type of asset or risk? Performance attribution is based on the assumption that the investment process contains both top-down and bottom-up processes, as listed below:

- The top-down process consists of risk allocation, where the fund attempts to determine the total amount of investment risk compared to, or in excess of, the investment risk of the pension liabilities;

- Next, the strategic asset allocation choice benchmarks the choice of asset categories to maximize return, given the amount of investment risk the fund can take;

- Within each of the assets, the fund can tilt the portfolio towards specific currencies, regions and investment styles;

- From a bottom-up perspective, once the investment styles and mandates have been determined, the manager can be asked to generate outperformance compared to a benchmark, or to stay close to a benchmark.

All of these steps can be compared to a benchmark, and performance attribution determines the additional return (called alpha or outperformance) relative to the additional risk for the over- and underweight choices for each of these steps. If the board has defined clear steps and decisions in the investment management process, and it is able to attribute performance and risk to it, the board can then have an informed discussion on whether each of these steps add value to the fund's goals, and determine whether (i) there is a clear rationale for why this decision adds value, (ii) this added value is proportional to the additional transaction costs that have to be made, and (iii) whether the added value does not consume a disproportionate amount of the board's or investment committee's time spent monitoring and managing.

Different approaches to defining steps in the investment process or attributing performance can produce very different results. It is important for a board to be aware of these differences and why they occur. Here are some key points to consider when interpreting an attribution report:10

- The most relevant attribution report is one that is in line with the investment process. An attribution report on sector-level is not useful, if the fund does not use sector allocation decisions;

- The ability to drill down from the top to individual managers is the most useful tool in making sense of the results;

- Performance measurement involves some degree of approximation. The order of magnitude matters more than the actual number;

- Frequency matters. A quarterly report will reveal more volatility and might spur unnecessary reactions or choice, compared to a yearly report;

- Consistency in the performance attribution measures must be imposed, so stick to the standard deviation, tracking error vs. benchmark or liabilities as much as possible;

- Performance evaluation requires multiple key measures during the evaluation, not the monitoring. Evaluation has a lower frequency, once a year or every three years. Monitoring ranges from daily to quarterly.

THE INVESTMENT POLICY STATEMENT

Broad investment policy is the domain of the board of trustees. An investment policy documents the issues that the board must address, concentrating on the desired outcomes.

The key choices in the investment management process, especially those on a strategic level and those guiding the implementation, are often formalized in an IPS. This is an important document. Writing down these choices might seem bureaucratic, but it is vital for there to be any chance of long-term success. It is a visible demonstration that the board has interpreted the wishes of its participants in a prudent, workable manner. The documentation also provides guidance for all the parties involved in carrying out the various activities for fulfilling the fund's goals. At times, the policy statement provides much-needed consistency in the board's decision-making. New and existing board members alike have to work within these boundaries, allowing the fund to commit itself to difficult choices beforehand, thereby avoiding behavioral biases. The IPS not only provides to the investment committee the strategic outline for achieving the fund's long-term goals; it also helps the fund deal with the various parties who are concerned with the investment returns: participants, sponsors, regulators, and other non-committee trustees of the fund.

The IPS describes the investor's risk tolerance, return objectives and expectations, liquidity needs, and other constraints. It may be drafted in relation to a fund's entire financial position or only to the portfolio under consideration. Traditionally, an important part of the IPS has been the strategic benchmark portfolio: what asset classes are to be included and in what proportions. Increasingly, the reasoning behind the choices of benchmarks, investment restrictions, and rebalancing policy has been included. Such an integral statement provides the investment management organization with a practical and useful guideline for setting long-term exposure to systematic risk and making decisions on manager hiring, tactical (i.e. shorter-term) asset allocation changes, and other investment implementation choices.

Developing and maintaining an IPS is a requirement in many countries. Under the Pension Act in the UK, pension schemes are required to have a statement of investment principles (SIPs),11 which is essentially an IPS. In the EU, institutional investors are required to have a SIP under the European Investment Directive. In the United States, however, there are no nationwide requirements for adopting SIPs. Pension funds in the United States are usually subject to state legislation, so regulations may vary across states. In recent years, pension funds have in any case adopted SIPs/IPS, in line with the trend in other regions.

An IPS includes:12

- The purpose of establishing policies and guidelines;

- The duties and investment responsibilities of parties involved, particularly those relating to fiduciary duties, communication, operational efficiency, and accountability. Parties involved include the board of trustees, any investment committee, the investment manager responsible for implementation, and the custodian;

- The strategic mission of the investments: goals, objectives, and constraints. Funds' objectives are usually formulated in terms of required or expected return;

- The level of risk tolerance and investment risk that may be incurred to realize the return, and the investment horizon required;

- The core investment beliefs, and the resulting investment “philosophy” codify guidance as to how the portfolio will be managed;13

- Any considerations in connection with portfolio construction to be taken into account in developing the strategic asset allocation;

- The asset mix of the portfolio's various asset classes;

- The asset classes to be included, described at a more general level than investment strategies and investment style(s);

- The vision for manager selection;

- Guidelines and methodology for rebalancing the portfolio based on feedback;

- Performance measures and benchmarks to be used in performance evaluation;

- The schedule for review of investment performance as well as of the IPS itself.

The IPS should be reviewed on a regular basis to ensure that it remains consistent with a fund's circumstances. An IPS is generally reviewed every three years, and in between when material changes occur in objectives, time horizon, or other fund characteristics.

The drafting of the IPS should be tailor-made for the fund, and is actually not as complex as it may sound. Just by looking at the current portfolio, you will be able to distill the implicit beliefs. Writing them down prompts the next step: do you agree with these beliefs? Does your fund have the resources, skills, and risk appetite required to implement them? Equally important, are they actually your beliefs, or do they in fact just reflect what your asset manager says? A goal for an asset manager might just be a means to an end for the fund. For example, pension funds do not necessarily crave “alpha” returns, just as most of us do not really crave a hammer and a nail. The hammer and nail are just unavoidable tools for putting a picture on the wall, which is what you really want. So the questions for the investment policy are what you really want (higher stable returns), what tools you need, and what tools you can do without.

It is the investment manager's role to convince you of the new investment strategy or instrument. And most of the time, this is a good thing. We manage portfolios in a far more informed way and with much better tools than we did 10 years ago. But once again, the investment manager's interests are not identical to those of the fund. So ask yourself, if you cut the expected rewards by half, would you still hire the new external manager? When they project 0.6% excess return per annum, would you settle for 0.3% and still hire them? In other words, manage your own manager's expectations. Which oftentimes means toning them down.

Although the investment policy is reviewed every year, changes tend to—and should—be incremental. Behavioral finance shows that investors' decision-making is subject to biases. In a return-seeking setting, investors are highly vulnerable to herding behavior because, when making decisions, they tend to place the greatest weight on their most recent experiences. Without a framework for making asset allocation decisions, investors will find themselves adrift and more susceptible to getting caught up in the herd.

Trustees and investment committees are therefore well served by relying heavily on the IPS to guide their long-term investment decisions, thus avoiding some major pitfalls in behavioral finance. Many investors have quite a short-term investment horizon, especially in turbulent investment environments in which many react to losses by selling risky assets and moving to cash near the bottom of the market. The IPS counteracts this by providing guidance for the investment philosophy and rebalancing.

Finally, writing an IPS does not in itself prevent such herding behavior and extrapolations when the time horizon is not chosen correctly. If portfolio assumptions are adjusted on a frequent basis, trustees may become part of the herd in a subtle way. In the early 2000s, when the technology bubble burst, many institutional investors found themselves overexposed to equity allocations. This made sense based on what the funds had formulated in their IPS: when the goal is to maximize a portfolio's expected return and future capital market projections for equity are rosy, equities will tend to be over-allocated. A number of high-profile investment managers and funds actually increased their equity exposure just before the stock market downturn.14