CHAPTER 9

Monitoring and Evaluation

Key Take Aways

An important responsibility of trustees is, for all the parts of the process, to monitor and evaluate the overall strategy and selected investment managers. Once the board has decided on the investment strategy, who will implement the different steps and how these will be implemented (e.g. mandate, risk budget), the implementation is set in motion. At this stage, you will want to track whether your fund is performing as you expected in order to alter the strategy or its implementation if necessary. This is not an easy task, mainly because of the fact that capital market outcomes are noisy in the short term: this makes it easy to mistake bad luck (short-term underperformance) for poor skills, and base costly decisions, such as firing and replacing managers, on this. Many behavioral traps come into play at this stage, from a committee shifting into action bias by firing an external manager when there is an underperformance, to the disappointment of trustees, who spent a great deal of time selecting and hiring a manager who subsequently performed below expectations. A high manager turnover rate is a signal that reflects poorly on an investment committee.

Selecting mandates leads to a substantial amount of work for the investment consultants and staff. Yet, once the mandate is selected, most time is spent on monitoring, evaluation, and deciding when to switch managers. Typically, funds' track records on these choices are dismal. Over time, pension funds have cut the average holding period of mandates, but by switching mandates more often, they run the risk of creating opportunity costs that can depress the long-term results.

Following selection, investment committees tend to view monitoring the investments as their number one priority. The monitoring process is an extension of the selection process; the same issues considered in the selection process will be relevant in the monitoring process. Ongoing review will require the provision of information in order to monitor the key issues on which the selection was based. Even though monitoring is considered to be one of the key issues, little time is spent on considering its purpose or philosophy. In recent years, asset managers have increasingly provided information to boards and investment committees that help answer all kinds of questions in detail, and this should help pension funds in their monitoring process. However, more data can also stand in the way of better monitoring.

This chapter aims to help the board to organize the monitoring and evaluation process in a structured way. We define monitoring as the analysis of information about an investment project or mandate, undertaken while the investment is ongoing, i.e. is it doing what it was expected to do? Are there signals that this is not the case? Evaluation is the periodic, retrospective assessment of a mandate or investment project that might be conducted either internally, or by external independent evaluators. Evaluation has a more strategic nature than monitoring: Can we improve our strategy? Are there better alternatives to our strategy?

We also discuss the timeline in which a board or committee should switch from monitoring to evaluation. Is this a gradual process, or does is require a distinct decision?

MONITORING

Monitoring is the collection and analysis of information about investments of the pension fund, undertaken while the investments are ongoing. The pension fund can monitor the investments integrally, and even in cases where the trustees appoint an investment manager, in the eyes of the beneficiaries they remain responsible for the investment of the assets of the fund.

Trustees monitor the performance of their appointed investment manager or of the performance of their own organization while they are managing. There is little doubt that a good investment performance enhances the achievability of a pension's promises, while poor performance weakens that goal. Under a defined contribution (DC) scheme, a member's benefits will even be directly determined by the returns earned on the contributions that were paid. It is vital that trustees know that their fund is delivering the necessary investment return within the objectives and restrictions. A pension fund's board, therefore, monitors developments at different levels (see Exhibit 9.1).

EXHIBIT 9.1 Monitoring of performance and risk along the investment process.

At the balance sheet level, the board considers whether its goals are (still) achievable. Are the investment returns of the total portfolio, as well as the investment returns relative to the returns of the liabilities, within the risk appetite and other bandwidths set by the board? The board monitors the following aspects:

- Model risk, resulting from using insufficiently accurate models to value the cash flows that need to be generated to realize the goals of the pension deal. This includes the inability to correctly predict factors that influence the cash flows such as longevity, wrong financial market assumptions like the discount rate, or the uncertainty of the size of cash flows due to complex optionalities and triggers agreed upon within the pension deal.

- Risk appetite, which arises when the liabilities of the pension fund cannot be perfectly matched with the existing assets. The board can manage this risk by monitoring deviations and recalibrating where appropriate.

- Strategic investment risk, arising from the failure of the selected long-term investment strategy to deliver the level of expected return or risk characteristics necessary to meet the fund's objectives. The board monitors this risk regularly by observing whether the realization of the fund's objectives move within the appropriate long and short-term risk measures and limits defined in the risk appetite.

- Tactical investment risk, occurring when the asset allocation is intentionally moved away from the long-term (strategic) allocation, if this is agreed upon in the investment policy and portfolio construction. This may arise where the manager or team takes the view that, in the short-term, such an allocation can improve the risk-adjusted return of the fund. However, it is possible that these positions may cause losses, or may (because of their scale) distort the strategy of the fund. The board monitors this risk by monitoring the level of risk and performance throughout the period of deviation.

At an operational level, the board monitors the implementation risk as a result of the execution of strategies. Implementation risk comprises:

- Other risks, which arise due to the mismatching of assets and liabilities. These include counterparty risk, currency risk, liquidity risk, or concentration risk. The board monitors the level of these risks, and whether they move within the bandwidths set by the board. Mandate compliance risk concerns the individual mandates and strategies in accordance with investment and risk guidelines. When the board appoints a manager, it also sets a performance benchmark, tracking error expectations, alongside other guidelines. The board then monitors its managers against a range of qualitative factors that it believes supports the manager in achieving its goals.

- Investment management organization. These are the activities of the investment management organization (or external advisor) that is hired to select and monitor the individual mandates and execute the overall strategic policy in line with the set guidelines.

Monitoring is a forward-looking process. Will the whole set of key decisions deliver the objective over the relevant horizon? The key is to avoid backward-looking bias. Four aspects stand out in monitoring:

- What to monitor and how to interpret and analyze the data;

- What scope there is for the committee or board to learn from monitoring;

- What biases should be avoided by the committee or board;

- When should the committee or board switch from monitoring to evaluating, i.e. deciding if the mandate is still the best choice for the fund or whether it should be replaced.

What to Monitor?

If monitoring is considered to be one of the key issues for a board, it helps tremendously if the board spends time on the purpose of and its approach to monitoring. Monitoring should be done on the basis of a set of criteria determined in advance. The information provided in the monitoring process reflects these criteria, not irrelevant noise, because that will distract the board from giving proper attention to what matters. If you look at your investment strategy, these criteria should represent a coherent set of design and implementation decisions, probably with a number of layers. For example, top down, you have decided on five steps: your strategic asset allocation, the rebalancing method, investment styles, the benchmarks for the different asset classes, and the implementation of the strategy via a number of mandates. These five decisions should be monitored. In the report, the board should be able to see the changes in portfolio return and cover ratio, decomposed into the steps, as well as the target risk or return bandwidth that the performance of each step should move between. All in all, 10–15 decisions about strategy and implementation will determine more than 95% of the outcomes; and among those, a much smaller handful will determine 80%. It will help the board's monitoring to have all these decisions listed and monitored on a single-page overview document.

The more strategic a decision is (such as the share of equities and bonds), the higher the impact on the risk and return, and therefore on the realization of the objectives of the fund. At the same time, the more strategic a decision is, the longer it will take to get feedback on the strategy. As mentioned previously, we encourage monitoring of the outcomes of the key choices globally in order to maintain oversight. Compare all the strategic choices you have made to a single giant machine that is built to deliver the outcomes that realize your objective. So, the first line in the monitoring report is the overall realization of the objective (e.g. inflation +4%) on a relevant horizon (for example, five years).

This forces you to focus on what matters and avoid wasting your energy on insignificant mandates that will never materially affect the realization of the fund's objective—merely giving you the illusion that you're working very hard.

Monitoring is “management by exception:” only the mandates and strategies that deviate from the defined set of performance and risk criteria or from the expected behavior for an investment manager should be discussed and need to be dealt with in a swift manner. When deciding on a component of the strategy and its implementation, essentially what you always do is form an expectation about its contribution to the realization of the fund's objective. At the same time, you will have ideas about the characteristics of an asset, for example, on a certain horizon. If it veers outside of these boundaries, questions arise about whether you really have bought what you expected and, therefore, whether this part of your strategy will make the expected contribution to your objective. Making these boundaries explicit ex-ante is key to a high-quality monitoring process, because (i) it forces you to think about the key issues, and (ii) once you have decided on the key issues, you can monitor these and forget about an enormous number of trivial issues that might distract from what really matters.

Monitoring as a Multidimensional Process

Monitoring should be multidimensional. Generally, the main focus tends to be on realized performance. But performance is only the output of the process, and largely coincidental—especially over a short horizon. Therefore, it is easy to draw the wrong conclusions from performance. This will potentially lead to “false negative” and “false positive” errors. In the case of a false negative, you incorrectly judge a strategy as being bad (e.g. based on disappointing short-term results). In a “false positive” you incorrectly judge a strategy as being good, e.g. based on historical results. Academic research shows that these errors have many repercussions: “false negatives” lead to excessive firing, and the subsequently hired managers have typically been doing well recently, which is why they were shortlisted by consultants. Remember that decision-making should always be forward-looking and that historical outcomes form a bad guide to the future. This is where the “multidimensional” side of the monitoring process comes into play. Once you know that realized outcomes have very limited meaning, you should concentrate on the inputs, the process and the people creating the output to look for clues about the viability of your strategic decision going forward: a great cappuccino is the product of the ingredients, the coffee machine and the person making the cappuccino!

Monitoring the Policy

Policy Monitoring ex ante should focus on the question “Are we doing the right thing?” In other words, what can go wrong? Will this impair the mission of the fund? Can these risks be mitigated or can the fund adapt? How can it do so? How will it react when the risk hits? Proper preparation prevents poor performance. So, the key drivers of the mission must be monitored. In order to do this, we need to use forward-looking scenarios and avoid looking in the mirror of history. It makes sense to distinguish short-term and long-term risks. Short-term risks will typically stem from short financial market movements and will pose a threat to the solvency or liquidity of the fund. But if you don't survive the short term, the long term is not relevant anymore. Long-term risks are slow-moving killers that can lead to shortfall: Are the premium and the long-term expected returns high enough to deliver the pension's promises? What if that promise is wage indexed and wage inflation turns out to be 2% higher per year than expected … for a 10-year period? Typically, short-term risks will get more attention than long-term risks, because that's the way humans are wired behaviorally. In the following paragraphs, both short-term and long-term monitoring will be worked out. In both cases of monitoring, the key questions to be answered by the board are: Are the risks acceptable? Can they (at least partly) be mitigated? How will we react if they materialize? How do we expect the outside world to react? And how will we communicate to the outside world? Be aware that you have to insure the house before it is on fire; often, when a risk hits it is too late to act and you will pay a high price for doing so. In addition, the bigger you are, the less room there is to maneuver.

For the short-term policy monitoring solvency and liquidity are the most important topics. Many trustees have vivid memories of the financial crises of 2008–2009, and perhaps of earlier crises such as the dot-com crisis in the early 2000s. The next crisis will certainly be different. However, we know that financial market crises, independently of their root course or the event that acts as a tipping point, will form a combination of rapidly collapsing prices of equities and related assets, as well as the temporary drying up of liquidity. Correlations between assets will typically increase, so funds can forget about short-term diversification. In the last few crises we saw decreasing interest rates, as central banks have been accommodative. Therefore, going forward it might make sense to also look at rising interest rates and bond yields. Liquidity will disappear (at least for some time) and the future will seem to be hidden in a in a cloud of uncertainty; it takes time to figure out what has happened and what will happen. So, the key to monitoring is this: build a number of scenarios for what could happen on a one-year horizon, and whether the resulting solvency and liquidity are within acceptable bands. Or, conversely, what needs to happen on financial markets to get to the lower border of acceptable solvency or liquidity, and how does that compare to historical movements of markets. These stress tests are helpful. Avoid using probabilities for this type of monitoring, as they will always provide information like, for instance, that there is a 1 in 20 probability that you will end up with a solvency lower than X. When markets are in crisis mode, probabilities mean nothing.

For the long-term monitoring process, shortfall is the most important source of attention. Monitoring the risk of not being able to meet the long-term promise is an important part of the policy process and should be a part of the Asset Liability framework. We would suggest monitoring this with a horizon of 5–15 years. This horizon is long enough to steer with available instruments to earn the expected premiums and should be long enough to dampen short-term fluctuations of capital markets. On the other hand, if the horizon of the analysis is too long, people tend to either not care, or expect that some sort of magic will happen. A good analysis will uncover the critical variables, which tend to be generic on a global scale. These can lead to questions such as: What if returns turn out to be significantly lower than expected? What if the discount rate falls even further? What if there is a significant inflationary shock? What if people live longer than what we currently expect?

Only one out of four of these questions is investment related; the other three are liability related. There is a tendency to hope, or even expect, that the investment returns will solve the problem. This can lead to boards postponing other available measures; these can take two forms or a combination of those. First, raising the premium that goes into the fund, or second, lowering the promise—by, for example, increasing the pension age, making indexation more flexible, closing down defined benefit (DB) funds and turning them into DC funds, etc. Because of the slow-moving nature of pensions, the earlier you identify potential risks, the easier it is to gently steer it back in the right direction.

In terms of frequency, we suggest that you monitor both the short and long-term risks in a formal way at least annually. On top of the annual monitoring, the investment management organization could provide you with a “management by exception” monitoring framework, a type of red flag system: only if something significant happens is there a reason to revisit the outcomes. In such a system, it is important to explicitly predefine what these flags may be, for example, “If the stock market declines by more than 15%, we will revisit the solvency risk.”

The Position of Monitoring on the Investment Committee's Agenda

In many funds, monitoring and evaluation are delegated to the investment committee. The investment committee should have a thorough understanding of the strategy that has been approved, and make sure that it has a realistic view of what to expect, in which circumstances, and on which horizon. The investment committee should monitor not only outcomes, but also the critical inputs and the process leading to these outcomes.

Given the fact that the board's and investment committee's time is always limited, we propose that strategic issues should come first on the agenda and monitoring, later. Our proposal is to put the ongoing monitoring in the second half of the agenda, it being management by exception aimed at picking up early warning signals. When an exceptional situation pops up (i.e. one of the parts of your investment process shows signs that worry you), this could raise a strategic question that should be put high on the agenda. If calibrated correctly, a handful of those exceptional scenarios should reach the investment committee or the board during the course of a single year.

What Is the Optimal Frequency for Monitoring?

Monitoring follows strategy. One concern is that the “management” horizon of many funds has become increasingly shorter, despite the fact that they are long term in nature and serving the long-term objective of their participants and clients. From this perspective, monitoring frequency should be once per quarter at most, definitely not more. You may ask yourself why it should not be done semi-annually. Consider this: If you feel like you cannot wait half a year to look at outcomes, is your strategy actually based on a strong enough foundation? Do you want to micromanage? Do you trust the people to whom you have delegated? Do you trust your own strategic decision-making? It is important that you force yourself into this “thinking slow” mode.

Monitoring Should Be Based on a Sound Approach: It Should Never Be a Mechanical Exercise

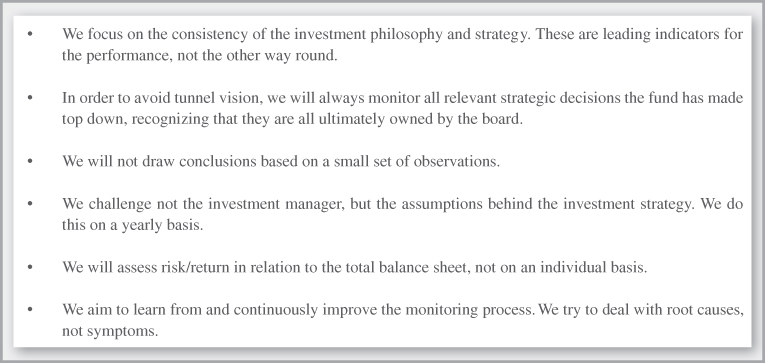

A practical way of avoiding biases is for the investment committee in charge of monitoring to stipulate a number of guiding principles for monitoring that can be communicated to the executive office or fiduciary manager, with the requirement that monitoring be performed and reported along those lines. An example set of guiding principles for monitoring is presented in Exhibit 9.2.

EXHIBIT 9.2 Set of guiding principles examples for monitoring.

David Neal, Chief Executive of the Australian Government Future Fund, promotes an alternative monitoring approach, supporting what he calls “immersed monitoring:” “This model promotes trust and enhances confidence to invest for the long run. It does so by deflecting attention away from short-term performance, toward aspects like decision processes, behaviors and alignment. […], the Future Fund has intentionally pursued engagement and common understanding of investment decisions. This includes regular reviews to identify and reduce any gaps in understanding around objectives and beliefs, and ongoing opportunities for the Board to review the entire portfolio and be included in its positioning. To build common understanding and ownership across the internal investment team, a ‘single portfolio’ concept was established. […] the Fund pursues a relatively smaller number of significant and close relationships which afford greater scope for monitoring via engagement.”1

WHAT TO LOOK FOR IN MONITORING

Developing a monitoring approach requires the board to know which steps and goals in the investment process need to be monitored, as well as which restrictions or guidelines need to be applied; otherwise the monitoring information is just data, and a monitoring approach. That being said, monitoring is a challenging task. While many boards and committees request the monitoring information, they only spend a small amount of time discussing it.

Good monitoring starts with setting the right expectations. The normal measure of the investment performance monitoring of a fund is a comparison with an equivalent benchmark portfolio or with other pension funds that are of a broadly similar nature. Over time, the performance will develop in line with, above, or below a benchmark. This simply is an observation, and does not actually inform trustees. At the selection phase, the board should have agreed on performance measures relating to the mandate's goals. For example, a mandate investing in so-called value stocks will need between 10 and 20 years to deliver the required return/risk trade-off. Any evaluation horizon shorter than 10 years undersells the potential value of the strategy and might even lead to perverse results: the reported standard deviation could be higher than other strategies and might lead to the conclusion that it does not add value after all. So, for the individual strategies, what to expect from the strategy in terms of risk and return and what horizon was assumed when selecting the strategy should be made clear for effective monitoring. In fact, one could argue that the ideal horizon for a mandate is an infinite one.

The “what to expect” part is also directly linked to performance and risk measures. When a board awards a manager an equities mandate with a tracking error of 2%, it then expects that the results will fluctuate around the benchmark on a yearly basis. The basic statistics tell us, 7 out of 10 times, to expect a performance between −2% and +2%, and 19 out of 20 times they tell us to expect a performance between −4% and +4%. Therefore, when a manager realizes an underperformance in the first years, the board would rather have it be otherwise, but it should not be surprised. The board has to monitor these risk measures and keep the horizon in mind that the board seems fit for the strategy. Patience is a necessary virtue, because positive excess returns are inconsistent, even among managers who outperform over the long-term.2

A first challenge is that performance reports are published often, for example, every quarter. If the reports show three subsequent quarters of underperformance, how should the committee react? The temptation will be to extrapolate these quarters and conclude preemptively that the manager will not live up to expectations, possibly ending the mandate early and creating opportunity costs. Therefore, reiterating the investment style, the horizon, and what to expect from the performance and risk measures in the short term is a crucial part of monitoring and monitoring reports, raising the hurdle for taking unnecessary action.

The tracking error example highlights a second challenge in monitoring. When managers or strategies are compared to their benchmarks, the results tend to be positive as well as negative on a monthly or quarterly basis. Trustees' and investors' attitudes towards risks concerning gains may be quite different from their attitudes towards risks concerning losses. Investment committees and asset managers are no exception. When choosing between profit opportunities, risk aversion prevails. On the other hand, when confronted with loss-making alternatives, people often choose the risky alternative. An active manager with positive alpha will become risk averse, locking in his profits, while the opposite is true with negative alpha.3 So when monitoring the manager, a board should repress its initial reaction to put pressure on the asset manager to improve their results when they are negative. Rather, they could focus on performance measures in the monitoring that provide insight into the consistency of the manager, such as the percentage of outperformance periods, complemented with other measures about the investment style.

A third challenge is the board having to be aware that if monitoring is delegated to investment committees, that the investment committee members are also prone to behavioral biases. For example, investment committee members with an investment background will view a drop in the equities markets as an opportunity to buy equities cheaply, aiming to earn money with cheaply priced equities, subsequently advising the board to do so. On the other hand, pension fund trustees, when confronted with a drop in the cover ratio, might come to a different conclusion, selling more equities to protect the pension rights as much as possible. An investment committee is a delegated monitor on behalf of the board. This means that the board should be clear on what to expect in the monitoring. Having a sound set of investment beliefs, risk appetite, and clear investment guidelines will help the investment committee monitor the market movements from the viewpoint of the board, and provide advice if needed. Thus if the board and committee have done their homework, investment strategies and mandates will be monitored regularly, but changes will be made at a very low frequency. Avoiding turnover is still one of the best performance choices for a board.

It is important that the board or investment committees think about the wider use of the monitoring information. Can it be used for providing feedback, for example? Feedback loops are particularly effective when it comes to monitoring. When people are assigned a goal and given meaningful feedback regarding their performance relative to that goal, they will use the feedback to adjust their actions to better match the goal. A feedback loop involves several distinct stages.4

- Gathering monitoring information. A behavior must be measured. This consists of three types of information: (i) the performance and risk measures agreed upon in the investment management agreement, (ii) data about the pension fund's investments and balance sheet, and (iii) external sources and opinions regarding the investment style and strategy in general.

- Linking information to monitoring goals. The information must be relayed to the investment committee, not in the raw-data form in which it was captured, but in a meaningful context. This is compiled by the investment advisor, the fiduciary manager, or the staff. A monitoring dashboard is compiled to show whether the manager is sticking to the chosen style and working within the preset limits, and whether the investment style is still valid in general.

- Giving feedback. The investment committee can give the feedback to the investment manager, give them the opportunity to adjust their behavior, and ensure that the appropriate action is taken by the manager. For example, the committee can see in the monitoring reports that the level of observed or experienced risk is inconsistent with predetermined limits, prompting questions to the investment manager if anything has changed in the investment style or way of operation. If the manager adjusts their behavior, that action is then measured and the monitoring resumes. In other words, the investment committee or board must be able to adjust choices to make sure that things are still done right.

Effective monitoring requires good (factual) reporting. Reporting should provide decision makers with the right key objectives and facilitate them in making the right decision. Every report should be based on facts and verified information. Committees should not have to question or doubt the quality of the data, and the report should be free of errors and redundancies. Finally, every now and then the setup of the report should be discussed. The following factors are of importance:

- A report should contain the key factors that were decided on at the time of the selection of the mandate, namely the investment style, and the key measures of its consistency. If a mandate is considered to be a value mandate, is the book-to-market variable chosen to make this investment style explicit in the monitoring?

- The relevant investment horizon. Going back to our previous example, a value style easily needs 15–20 years to be effective, significantly longer compared to an investment grade mandate that only needs 5–8 years. In order to avoid short-term action bias, it is important to keep in mind the time horizon that was set in the report.

- The most relevant attribution report is one that is in line with the investment process. This type of report provides a breakdown of the type of investment decisions whose risk (ex-ante) and returns (ex-post) trustees should be focusing on in the performance attribution. Ideally, the external manager has indicated in the selection process which of these investment decisions he or she considers to be a competitive advantage. In this way, it can be monitored as to whether the claims of the manager turn out to be valid.

- A performance attribution that also integrates risk attribution. Absolute vs. relative risk/return measures, where risk information is added to return (attribution) information; as well as downside risk measures (especially stress loss estimates) that could inform trustees of the “worst case” scenarios, the mitigation measures available and how they can be better prepared in the event of another downward market scenario.

- The ability to drill-down from the top down to individual managers, an extremely useful tool in making sense of the results.

- Performance measurement involves some degree of approximation. The order of magnitude matters more than the actual number.

- Deciding on the frequency of reporting. Compared to a yearly report, a quarterly report shows more volatility and might spur unnecessary reactions or choice.

In the minutes of the investment committee or the board, be explicit about the decisions you have made with regard to monitoring. Specifically, be as explicit as possible about the arguments, and evaluate them over a longer period. Is it one factor, such as relative performance, that drives many of the concerns and decisions? And is this consistent with what was agreed upon with the external manager?

WHEN DOES A BOARD MOVE FROM MONITORING TO EVALUATION?

When the mandates and strategies are selected, the monitoring should be based on the idea that mandates are kept indefinitely, and monitoring should be designed accordingly. If nothing had changed since the original selection, there generally would be no need for an evaluation. So periodically, a good question to address in the monitoring process is what (if any) assumptions have changed since the original decision was made. There are three areas where changes might take place:

- Needs. Have the needs of the plan and its participants changed? For instance, changes in plan demographics (e.g. an aging participant population) may necessitate a reconsideration of the plan's risk appetite or strategic asset allocation. A dramatic increase or drop in the size of the plan (plan assets or number of participants) could also necessitate a reconsideration of the types of mandates and its instruments.

- Style and strategy. Has the investment strategy or style changed? Has the investment fund/manager/service provider or its performance changed? Is the manager sticking to the stated investment style? Have managers left? Are quality targets being met? Are performance targets within an acceptable range? Is the investment strategy still sustainable? An active equities strategy that focuses on a specific niche might attract more investors over time, decreasing outperformance potential, at some point perhaps not even covering the costs. A question to ask beforehand would be whether such strategies are worth including in the portfolio, as the monitoring is then more resource intensive and time-consuming.

- Market. Has the market changed? If, for instance, the costs of an investment strategy in the market have gone down on average, then a review of what the plan is paying for these services (compared to the new market conditions) may be in order.

If one or more changes are identified by the investment committee or the board, then it makes sense to plan an evaluation in order to assess whether the strategy is still fit for purpose or whether it should be changed. Before deciding to move from monitoring to evaluation, the board should take into consideration the fact that the cost of hiring and firing is always high. It is useful to have a reliable estimate of the cost of replacing a manager. This can be very substantial, including search cost, market impact, etc.

A seminal study analyzed the selection and monitoring processes for 3400 institutional investors between 1994 and 2003.5 Managers for new external mandates are hired after a period in which they have realized substantial outperformance compared with the incumbent manager. However, when the manager is hired, this outperformance differential dwindles. Rather, the fired manager produces a 1% outperformance on average. If the search and selection costs, costs due to switching managers, and opportunity costs due to differences in performance are combined, then the authors estimate that 5%–10% of performance is lost. When institutional investors base their hiring and firing decisions primarily on past performance, the lost performance gap further increases.

Armed with this knowledge, you now see that you cannot be sure that the new manager will be better than the old one. Therefore, we would argue that, if possible, you should work with existing managers on the continuous improvement of their strategies.

EVALUATION

The previous paragraphs described monitoring as the collection and analysis of information about an investment project or mandate, undertaken while the investment is ongoing. Evaluation, on the other hand, is the assessment of a mandate or investment project. It may be conducted internally or by external independent evaluators, and many investment committees and boards consider evaluation to be part of monitoring. While this might work in practice, it is worthwhile separating these activities, because they actually have different roles. It is helpful to stress the key differences between evaluation and monitoring:

- Evaluation is strategic in nature—monitoring is operational;

- Evaluation looks back and draws lessons geared towards learning to make better decisions in the future—monitoring is a “real time” activity;

- Evaluation has a learning perspective—monitoring has an investment compliance perspective.

Evaluation is the systematic assessment of the mandate or investment project. Evaluation involves assessing whether monitoring has paid off, whether the selected mandates fit within the investment plan, what decisions have turned out to be wrong or right, and whether there are lessons somewhere for the board and the investment committee. Evaluation aims at determining the relevance, impact, effectiveness, efficiency, and sustainability of investment strategy as well as the contributions of the decisions and style to the results achieved.6

Evaluation takes place on a number of different levels, depending both on the goals and objectives of the mandate, and the scope of activities and strategies being designed or implemented. For example, evaluation would look different for peer-based comparison; a balance sheet approach where the results are evaluated in relation to the fund's overall goals; a stand-alone basis, compared to the pre-defined benchmark; and an environmental, social and governance perspective. An evaluation should provide evidence-based information that is credible, reliable, and useful. When evaluating managers based on quantitative measures, it is advisable to:7

- Consider several different measures, as each provides different information;

- Understand how the various measures interact with one another;

- Compute the measures during different time periods of interest, where longer periods (three to five years) should be dominant in discussion. Avoid short time periods, except for compliance reasons. This induces boards to take unnecessary action;

- Recognize that all measures are by definition backward-looking.

This list of measures is a starting point to include in an evaluation:

- Information (or Sharpe) ratio. The manager's excess return above a benchmark, normalized by the standard deviation of relative returns;

- Sortino ratio. The manager's excess return above a benchmark, normalized by the standard deviation of downside relative returns;

- Win–Loss ratio. The manager's average positive relative return divided by the manager's average negative relative return;

- Hit ratio. The percentage of periods where the manager's relative returns were positive (a.k.a. the “batting average”);

- Correlation coefficient. The correlation of the manager's excess returns with the returns of other existing (or prospective) managers;

- Correlation between beta and alpha. Alpha is earned from security selection, tactical asset allocation, or other investment skills. Alpha is scarce and, therefore, should be expensive. Beta, on the other hand, is return that is derived from exposure to a passive index or a risk premium. Beta is abundant and, therefore, should be cheap. It is essential to understand whether an active fund manager's returns are true alpha, or whether they could be replicated through inexpensive beta exposures. A high correlation between beta and alpha is a “red flag,” suggesting that the alpha is not skill, but leveraged beta exposures.

The findings, recommendations and lessons of an evaluation should be used to inform the future decision-making processes regarding the mandate. Evaluation should be evidence based, because for any given strategy, there is a lot of data available to compare and learn from. In addition, making it evidence based helps to develop a more objective evaluation process, which is important in the investment sector where strong views and opinions from asset managers might influence decision makers. Surprisingly, very little empirical evidence has been built up regarding the effectiveness of selection and monitoring; in most funds the application of evaluation is still in its infancy.

In many funds, evaluation is delegated to the investment committee. Before starting to evaluate, the investment committee should have a thorough understanding of the strategy that has been approved, and make sure that it has a realistic view of what to expect depending on the circumstances and on the horizon. The investment committee should monitor not only outcomes, but also the critical inputs and process leading to these outcomes. It also helps to be aware of the latest academic insights on hiring and firing and the behavioral biases involved. If the committee determines that the total costs for switching managers amount to 10%–14%, this is a clear hurdle rate to overtake in the decision to evaluate and potentially hire a new manager. Firing managers and blaming others is “managing” symptoms, not effective governance. Evaluation should never be a one-way street. Ideally, the committee includes the investment manager or selected mandate. How would they self-assess the results on the basis of the criteria the board set? In their opinion, how would they attribute the results to the investment beliefs and investment philosophy? Finally, it is important to quiz the manager to understand how he views circumstances in the market, and whether there are any developments that might trigger a change in their investment style.