Chapter 7

How to Handle Questions

QUESTION-AND-ANSWER PERIOD

When developing your presentation, it is critical to prepare for the possible questions your audience may ask you during and after the presentation. This includes not only expected and regular questions but also questions that may be difficult to answer.

In the next few pages, I will provide you with a structure and format for both types of questions: regular, or straightforward, questions, and difficult, or hostile, questions.

THE FIVE-STEP PROCESS FOR ANSWERING REGULAR (NONDIFFICULT) QUESTIONS

Many presenters like to avoid the question-and-answer period following a presentation. For some presenters, this is the most dreaded part of the presentation. For others, this can be the most exciting part of the presentation. If you did a good job with your presentation, you will see your audience eagerly wanting to ask questions.

When dealing with questions, I like to use this five-step process:

What If No One Asks You Any Questions?

After you have completed your presentation and are transitioning to the question-and-answer period, there may be times when you ask the audience if they have any questions and wait and wait and wait but no one raises a hand. You might have a tendency to say yourself, “Thank God,” and make a quick exit. In my experience and in most situations, you will find that no one in your audience wants to be the first person to ask you a question. In these cases, I actually throw out the first question. It may start out something like this, “Many people have asked me. . . ” I then respond to that question as if someone from the audience actually asked me that question. I would offer one word of caution when you do use this technique: make sure you ask a question you can actually answer. You laugh but I have seen this happen to a few presenters. It is pretty embarrassing to be unable to answer your own question.

Another option is to avoid this uncomfortable situation all together—the silence can be deafening when no one immediately volunteers a question—or at least lessen the void by taking the following measures:

DEALING WITH DIFFICULT OR HOSTILE QUESTIONS

There will be times when the questions you are asked are difficult or even hostile. How you handle these types of questions is a little different. Keep in mind, that in many cases, the questions your audience will want to ask you may be difficult and it is your responsibility to provide answers to these questions. How you personally handle these questions can either add to or detract from your credibility as a speaker.

There are a few techniques that are typically used when dealing with difficult questions. I will first describe each technique and then provide you with an example.

Technique 1: The Delay Tactic

Say someone asks you a question that you do not want to answer immediately. This may be because (1) you do not know the answer to the question or (2) you do not want to answer the question because you need time to think about the answer. What some speakers do, and this a technique I see politicians use all the time, is to immediately turn their attention to someone else who had just asked a question and say something like this (while looking at the person who asked them a question earlier), “You asked me a question earlier about. . . ” At this point, when you are the speaker, you can respond by providing additional information to the question you were asked earlier. What you are actually doing is stalling for time as you think about how you will answer the difficult question. This is an attempt to buy some time to formulate your answer or response to the difficult question. You then go back and ask the person who asked you the difficult question to repeat the question again (again you are stalling for additional time). You are now better prepared to respond to this question. One word of caution; you can probably use this technique only once during your question-and-answer period. This also assumes that you were listening carefully to the question earlier and still are thinking about the response to that question in the back of your mind.

Technique 2: The Compound Question Tactic

There will be times when someone in your audience says to you, “I have a two questions. The first question is [question 1] and the second part of the question is [question 2].” This is not uncommon with presentations, and I have experienced this type of question many times. When I talk about this type of question during my presentation skills classes, I ask the participants in my class, and I will ask you the same now: Which question should I answer first? The first question or the second? (Here is where I am giving you a few seconds to think.)

My response to this question is, I always answer the easier question first. Keep in mind that the easier of the two questions may not always be the first question. I respond to the easier question, and then I ask them to repeat the other question (this is where I am using technique 1 to stall a little).

So what if you do not know the answer to one of the questions? What you do not do is say something like this, “Well I do not know the answer to the first question, so let me deal with the second part of your question.” Under no circumstance should you do this. What you are better off doing is to say something like this, “Let me deal with the second part of your question first.” You then respond to the second part of the question. Once you answered the second part of the question, you then ask them to repeat the first question. You then can respond to this question and if, for some reason, you do not know the answer to this part of the question, it won’t appear as awkward.

Technique 3: The Diffusion Tactic

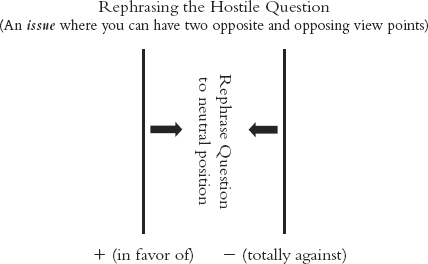

When you are faced with a difficult question that borders on being hostile, you use a diffusion technique. Say you are discussing a point of view and someone asks you a hostile question. (I will provide you with an example in a little while.) What you want to do is to (1) listen to the entire question, (2) think carefully about the question, and then (3) rephrase the question to a more neutral position. Referring to Figure 7.1, let me give you an actual example of a difficult question.

Figure 7.1 You want to rephrase the hostile question to a more neutral position (regardless of your personal position) and then respond to the rephrased question.

Many times the difficult question may arise from a very strong opposing viewpoint. Say, for example, you are in favor of an issue, and the audience member is clearly not in favor of the issue. You are on opposite sides. Your goal is to first understand where the other person is coming from and where his or her reference point is. You do this by first seeking to understand where the person is coming from without verbally passing any judgment. After asking a few clarifying questions, you will get a better idea and then can respond; however, in many cases, you do not want to engage in a dialog to do this, so you need to carefully listen to the question, make a quick mental assessment, and carefully rephrase the question to a more neutral tone without really changing the meaning of the question. After carefully rephrasing the question, you then respond to your rephrased question. What you are doing here is (1) repeating the question but (2) rephrasing the question to a more neutral tone.

Let me give you an example to make this clearer. Say someoneasks me during one of my workshops or seminars, “What makes you such an expert on public speaking and presentation skills?” If you look at this question carefully, you will note that the one phrase within this question is, “you such an expert.” You can just hear in your head the tone in the person’s voice while asking this question. What I do not want to do is to repeat this question exactly how it was asked. This would not diffuse or neutralize anything. After listening to this question carefully, I would repeat the question but rephrase it as, “You are probably wondering where I got all my speaking experience.” Look at my rephrased question closely. I replaced the “you such an expert” with “where I got all my speaking experience.” I would then respond to my rephrased question. Notice how I shifted the focus from me being an expert to one who has a lot of speaking experience.

Applying this technique smoothly and professionally will take some practice. Although this is not as hostile of a question as some can be, it does give you an example of how to apply the technique. During my workshops, I have each of the participants get up and try this technique while responding to questions from the other participants.

Technique 4: Just Agree with Them

One very powerful technique you can use when someone asks a difficult question or even makes a difficult statement is to just outright agree with the person (assuming you do agree). Many times, someone is not really asking you a question but making a statement, such as, “I really feel that [whatever the issue is] is stupid.” Your response (again only if you agree) is, “You’re right! It is stupid.” Then pause. This allows the other person to realize you just agreed, which will probably be a shock. You then soon follow up you response with, “However, I have found. . . ” You then provide some sage advice or response at this point. The key here is to show you agree first, but then you offer a solution for dealing with the issue. This technique can take the wind right out of the person’s sail.

How Do I Diffuse Hostility?

More Tips on Handling Hostile Questions