Three

Harold M. Bacon

Many great research universities have on their mathematics faculties one or two senior people who do not spend their lives producing important theorems but still contribute greatly to mathematics, both on their own campuses and more widely. They are often revered by their students for their classroom teaching and their mentoring. One such was Harold Maile Bacon, who, with his longtime colleague Mary Sunseri, played just such a role in the mathematics department at Stanford University.

Bacon came to Stanford as a freshman in 1924, following in the footsteps of his father who had graduated only a few years after Herbert Hoover, when Stanford was a fledgling institution at the end of the nineteenth century. Harold stayed on for graduate study, receiving his PhD from Stanford in 1933 under the direction of the eminent Danish analyst Harald Bohr, who was visiting Stanford at the time. Bohr, however distinguished as a mathematician, may have been better known as a champion soccer player in Denmark and as the brother of the Nobel laureate physicist Niels Bohr. Bacon, after a short stay at San Jose State, returned to Stanford in 1935 and rose through the ranks to promotion to full professor in 1950. He formally retired in 1972 but continued to teach until 1980.

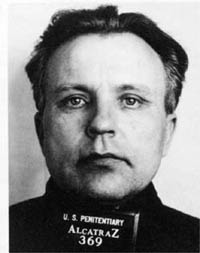

Figure 3.1 Harold Bacon was a legendary mathematics teacher who taught at Stanford for forty-five years.

A Legendary Teacher and Advisor

At Stanford he was a legend, having taught calculus and other subjects to generations of Stanford students. In 1965 he was given Stanford’s Dinkelspiel award for distinguished service to undergraduate education. Everyone I’ve ever talked with about mathematics at Stanford during Bacon’s years there remembered him, if not for having taken one of his classes then for having received from him the best advice on majors, careers, and life in general.

Figure 3.2 George Pólya and Harald Bohr, brother of Neils Bohr and Bacon’s thesis advisor.

He was a faculty member of the old school, formal in demeanor, always in suit and tie, often with a vest. He was somewhat courtly, polite, gracious, welcoming, and friendly. Yet he was always reserved, well aware of the distinction between faculty members and students. He married, rather late in life, another person deeply committed to Stanford, Rosamond Clarke, and they had one son, Charles, now a prominent geologist. They lived in the Dunn-Bacon house on fraternity row, near the famous Stanford Quad. It is a large neoclassical house that once belonged to Harriet Dunn, a cousin of his father’s. The interior was paneled and formal, with Victorian lamps and furniture consonant with Stanford’s Victorian origins. On the third floor was an elaborate model train layout for Charles. In front of the Ionic columns around the front door, a curved driveway was lined with rose bushes, where the Bacons were often seen tending their roses, Harold usually in attire more formal than that typically seen on gardeners.

Figure 3.3 The young Bacon family—Harold, Rosamond, and baby Charles.

Harold and Rosamond were the quintessential faculty couple, involved at all levels of campus life, known to everyone in the Stanford community, generations of alumni, and members of the Palo Alto community at large. In some ways they were the models of what one might at that time have thought of as the perfect Republicans—Episcopalian, socially well connected, and, in their lifestyle, conservative, indeed almost patrician. Of course, as often happened in their day, even with that lifestyle they were also politically liberal. Harold once told me the secret of getting through life is to trust in God and vote the Democratic ticket.

Figure 3.4 Charles Bacon, son of Harold, went on to a career in geology.

Rosamond was throughout Harold’s career no passive partner. She had worked for the university after she graduated and was an active member of the Library Associates and a founder of the Stanford Historical Society. John E. Wetzel, now professor emeritus at the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana, recalls that when he came to Stanford “the Bacons hosted a reception for new graduate students shortly after [he] arrived . . . and [he] remember[s] a wonderfully pleasant chat with Mrs. Bacon as she served tea . . . [S]he was so interested, friendly, and welcoming that I felt a real sense of loss when she left me to turn to someone else.”

Teaching Calculus to an Alcatraz Prisoner

Always involved in doing good works, the Bacons often helped unfortunate people in the community, even on occasion to the point of finding lawyers to get them out of jail when they were unfairly detained because of their background. In a much more serious case, well known to the campus community, beginning in 1950 Harold made trips to Alcatraz by launch from a pier in San Francisco to help a prisoner who was trying to learn calculus on his own. Alcatraz—“The Rock”—had housed some of the most hardened criminals in the United States, including Al Capone and “Machine Gun” Kelly. The prisoner, Rudolph “Dutch” Brandt (Reg. No. 369-AZ), had been convicted of killing a gambler in 1924 and subsequently of participating in a bank robbery in Detroit in 1936, after which he was sentenced to a twenty-five- to thirty-year term.

Brandt was almost completely self-taught, but, because there were no provisions for taking courses at Alcatraz, he enrolled in a correspondence course in calculus from the University of California. He had found working on algebra and trigonometry problems beneficial while in solitary confinement, a period that Bacon estimated to be between one and three years. While in what Brandt called the “dungeon,” he had essentially nothing to write on so he tore up pieces of tissue paper to form letters and numbers so he could work out a method of finding the solution of four simultaneous linear equations. At one point Brandt wrote apologetically to Harold indicating that he was sorry to take up so much of his valuable time. Harold wrote back: “Do not feel that [my] coming to see you is in any way a waste of my time regardless of what use the mathematics may be to you when you get out of the penitentiary. The greatest value to be found in your study of mathematics is, it seems to me, the satisfaction you get from the subject itself with the accompanying sense of achievement.”

Correspondence and visits continued until Brandt was transferred to a federal prison in Michigan, where he was allowed to develop skills working in the prison shop. Paroled in 1953, Brandt worked in a tool and die shop in Detroit, eventually moving to Cleveland. He continued to correspond with Bacon and on a trip east to attend a meeting of National Science Foundation (NSF) institute directors, Bacon stopped off to visit with Brandt, who was by that time suffering from terminal cancer. Much earlier Bacon had taken him books of tables to help him with his calculations and once gave him a specially autographed copy of George Pólya’s How to Solve It. For Christmas 1953, Rosamond sent Brandt a Stanford Christmas calendar and a picture of their son Charles, then five years old. Brandt, who earned only a meager salary, sent a $50 bill to Charles for Christmas, ultimately used to buy a new piece for his model train setup. Brandt died in late 1956. Details of this friendship were chronicled in some detail in a moving article by the Bacons’ friend Charles Jellison in “The Prisoner and the Professor” (Stanford Magazine, March-April 1997, pp. 64–71).

Harold had been alerted to Brandt’s efforts to learn calculus by Lester R. Ford, then at the Illinois Institute of Technology and a former president of the Mathematical Association of America. Ford had been corresponding with Brandt and had encouraged him to look at some mathematical problems. After visiting Brandt, Harold wrote to Ford to report on their encounters in the prison. He said, “. . . he is eternally grateful to you for what you have done for him. It means everything that you have addressed him like a man rather than a convict. He spoke feelingly (and there was a world of genuine pathos in this poor fellow) of his struggles to conquer the mathematical questions he had tackled. He now feels that he is winning his fight to learn. In this he sees his chance to get clear of the Underworld (his own words).” Jellison went on to say that “Bacon treated him as he did all his students, with respect and compassion. He shared his love of mathematics, ‘that handmaiden and queen of the sciences,’ with a murderer and a bank robber, and was rewarded by witnessing his transformation.”

Figure 3.5 Rudolph “Dutch” Brandt, a prisoner at Alcatraz. Bacon made regular trips to the prison to teach Brandt calculus.

Bacon carried on correspondence with prominent mathematicians (people wrote real letters in those days), notably Dunham Jackson, well known for his American Mathematical Society (AMS) Colloquium Series volume, The Theory of Approximation (1930) and his MAA Carus Monograph, Fourier Series and Orthogonal Polynomials (1941), as well as Harold Davenport, the eminent number theorist at Cambridge University. Correspondence with Jackson consisted, in part, of an exchange of their own limericks, albeit very proper ones.

Neither Harold nor Rosamond came from a family of academics. Harold’s father was an engineer for the city of Los Angeles and designed pedestrian walkways under city streets near public schools. Rosamond’s family came from Carpenteria near Santa Barbara. Her siblings married well. Her brother, Thurmond, was at one time the Chief Judge of the U.S. District Court for Los Angeles, and he married Athalie Richardson Irvine, the widow of James Irvine, Jr., of a pioneer California family that had developed much of Orange County, specifically the Irvine Ranch that lent its name to a campus of the University of California. Her sister, Sue, married a member of the Roos family, a prominent mercantile clan in San Francisco whose house on Pacific Heights is an architectural icon designed by the famous Arts and Crafts architect, Bernard Maybeck. Sue’s house in the fashionable suburb of Belvedere extended over San Francisco Bay and was called “The Stilted Manor.” Rosamond married an academic.

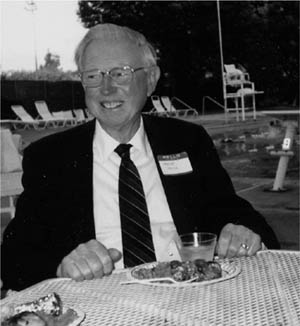

Figure 3.6 Professor Bacon enjoying lunch by the pool.

Dickens and Thackeray

Aside from their good works and his campus position, Harold and Rosamond lived rather quiet but comfortable lives, reading to one another at bedtime from their favorite works of Dickens and Thackeray, and they listened to Gilbert and Sullivan.

Always traveling either by car or by Pullman across the country, in the 1960s, after taking the train to New York, they sailed on the Queen Mary to England, where they stayed at Brown’s Hotel in London. It had opened in 1837 and proudly displayed, even in the 1950s, the rent in the lobby carpet where Elisabeth, Queen of the Belgians, once caught her heel when she lived there during World War II.

I first met Harold when I showed up on the Stanford campus in the summer of 1955 when I decided to take a look at housing and such just before my first year of graduate study there. No one else was around, so I wandered into Harold’s office (he was usually there whether school was in session or not), and he greeted me warmly and provided me with excellent suggestions on housing and what I might expect in my first attempt at teaching. After that first encounter I always felt that we were friends.

Figure 3.7 Harold Bacon and Harold Davenport at Stanford University.

Pioneered Institutes for High School Teachers

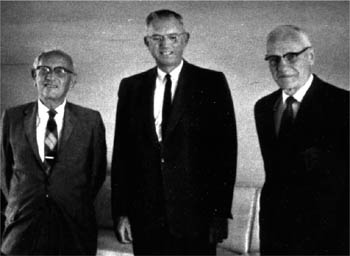

In the 1950s and up to the mid-1960s, Harold was a pioneer in introducing, with funding from the National Science Foundation and the Shell Foundation, a series of summer and academic-year institutes for high school teachers. The idea had been developed during conversations on a long drive with George Pólya to attend some meetings in Colorado. For these programs, which he started in 1955, he brought in outstanding faculty—H.S.M. Coxeter from Toronto, Carl B. Allendoerfer of the University of Washington, I. J. Schoenberg of the University of Wisconsin at Madison, Morris Kline from New York University, Ivan Niven from the University of Oregon, and D. H. Lehmer of UC Berkeley. The high point was a series of two NSF institutes held in Versoix, a village just outside Geneva, Switzerland, for teachers in American schools abroad. As a young faculty member I was fortunate to be asked to assist in the administration of these two institutes and to be able to teach in both of them, in 1964 and 1965, where Harold and I were joined one year by George Pólya and the other by Cecil Holmes of Bowdoin College. Our assistant was a recent PhD at the Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule (ETH) in Zürich, Pia Pfluger (later Korevaar), who went on to a career at the University of Amsterdam; she was the daughter of Pólya’s successor at the ETH, Albert Pfluger, when Pólya left Zürich in 1942. The administrator of the local Collège du Léman, where the institutes were held, referred to Harold as “Monsieur le directeur général” and to me as “Monsieur le directeur adjoint.” Happily, the instruction was in English.

Figure 3.8 Members of the NSF institute faculty in Versoix, Switzerland in 1964–65—George Pólya, Harold Bacon (“Monsieur le director général”), and Cecil Holmes of Bowdoin College.

When not in the classroom, we had to struggle along with our college French, which got us through from day to day except on a few occasions. When Harold backed our leased Peugeot into a wall and we had to negotiate with local repairmen to get the fender fixed, all we could do was point, since “fender” is not in Berlitz and is seldom heard in a college French course. And Harold, more inclined to go to church on Sunday mornings than I was, felt that part of my task of being “directeur adjoint” was to accompany him to the local Old Catholic Church, a nineteenth-century Swiss breakaway from the Roman Catholic Church, when going to the Anglican church in Geneva was inconvenient. He was more successful at appearing to know what was going on during those services than I was. I do recall, though, that one of the favorite hymns in the local church was sung in French to the tune of Stephen Foster’s “Old Folks at Home,” otherwise known as “Suwannee River.”

Figure 3.9 The “birthday lineup”: Albert Pfluger (October 13), Gerald L. Alexanderson (November 13), George Pólya (December 13), and Harold M. Bacon (January 13).

Of course, Harold’s influence was not restricted to his own teaching or his directing these teacher institutes. He wrote a popular calculus text (McGraw-Hill, 1942; second edition, 1955) that was much admired for its clarity and its beautiful problem sets, along with Introductory College Mathematics (Harper, 1954), co-authored with Chester Jaeger of Pomona College. Of the calculus text, Wetzel said, “I learned my calculus the first time I taught the course, from the [second] edition of Bacon’s Calculus, a book I used as a problem source throughout my teaching career.” Harold also published a beautiful piece on Blaise Pascal in The Mathematics Teacher (April 1937, pp. 180–85). One of the organizers of the Northern California Section of the Mathematical Association of America (MAA) in 1938, he served as the section’s first secretary-treasurer and remained active in the section for many years. He was elected twice to the MAA’s national Board of Governors and served on many of its committees, in addition to countless committees on the Stanford campus. An exemplary citizen of the campus and various mathematical communities, he was known widely in professional circles during his career.

In mathematics education he had great enthusiasm for the work of George Pólya and was the first person to call to my attention an extremely short and elegant proof by Pólya of the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality, using only the exponential function and the first two terms of its Maclaurin expansion.

Recently I had the opportunity to talk with a couple of experienced mathematicians who, like me, were teaching assistants at Stanford in the late fifties. We were amazed in comparing notes on our teaching over, now, many years to see how similar our practices have been and how much we learned from Harold Bacon about teaching, even down to the mechanics of grading, setting policies for homework and examinations, advising students on suitable courses, and answering their questions on careers. For example, he advised showing students scores on midterms and finals, listed in rank order, without assigning letter grades to any scores, so that students were not tempted to “average” letter grades, usually to their advantage. And he advised against any preset equivalence of ranges of cumulative totals of points and letter grades, since that presumed that the instructor always made up near perfect sets of examination questions. This goes a long way toward discouraging extended arguments with students about the final course grades. (They like to use the Peppermint Patty system from the comic strip Peanuts: “The way I see it, seven ‘D-minuses’ average out to an ‘A.’”) As a department chair for over thirty-five years in my own department, I have seen many examples of what trouble young instructors could get into by ignoring these simple procedures.

Sometimes Harold’s advice was just plain shrewd: when Howard Osborn was a beginning teaching assistant at Stanford, he faced the common problem of having a premed student who claimed after every test that she had to have an A “in every one of her courses because no medical school would accept her otherwise.” Harold advised him to agree to reread all of her quizzes and exams “very carefully . . . [and] find additional minor errors that were ignored during the earlier grading and that deserved a lower grade.” That tended to discourage further arguments. What we learned from Harold in those days as teaching assistants served us well through many, many years of teaching. In turn we have passed along to our own students his wise counsel.

In my experience, Harold Bacon’s legacy is very similar to that of many others on research university campuses, and their influence is long felt, even though their work is not recognized in the mathematical encyclopedias. They have been, however, truly outstanding mathematical people.

![]()