It may sometimes be expedient for a man to heat the stove with his furniture. But he should not delude himself by believing that he has discovered a wonderful new method of heating his premises.

The chapter makes a leap to macro thinking from the micro considerations of the last chapter. Though not shocking, it seems that what makes sense for the individual may not always make sense for the group. Highlighting how this paradox of aggregation operates, Paul McCulley notes:

Anybody who's ever been a spectator at a crowded ball game has witnessed the difference between microeconomics and macroeconomics: from a micro perspective, it is rational for each individual to stand up to get a better view; but from a macro perspective, each individual acting rationally will produce the irrational outcome of everybody standing, but nobody having a better view.[48]

In economic spheres, this fallacy of composition can be more extreme and have more dramatic impacts on society. Specifically, analysis conducted at an individual unit of analysis may not apply to groups.[49] Consider home finance. Though it may be reasonable for an individual bank to believe that it can foreclose and sell the house for a value in excess of the mortgage amount, this conclusion is very suspect when considering millions of homes simultaneously being sold. This latter case will crash the market for homes and result in significantly lower prices.

The underlying premise evaluated in this chapter is that debt and the amplification of debt by deflation can have deleterious impacts on individuals, companies, and in aggregate, markets. Before diving into the conditions under which these effects can snowball in dramatic fashion, we first review the mechanics of debt. More specifically, understanding leverage and how it impacts equity values is essential to grasping how debt exacerbates ups and downs into booms and busts. After describing the mechanisms through which debt amplifies returns, the chapter turns to a somewhat less traditional perspective on the role of money and credit in the creation of booms and busts—Hyman Minsky's Financial Instability Hypothesis. We then explore Irving Fisher's debt-deflation theory, as well as the Austrian Business Cycle Theory and conclude the chapter by integrating these perspectives into a single macroeconomic framework.

Suppose you purchased a house for $100 (a real steal!). Because you didn't have all the money needed to buy the house, you decide to take out a loan for a portion of the purchase price. The amount you put down will be your equity in the home, and mortgage value will be your debt. Now let us consider two separate scenarios. The first, called "Happy Times," is one in which the value of your newly purchased home rises by 10 percent. The second, "Sad Times," is a situation in which the price of your newly purchased home falls by 10 percent.

What happens to your investment in each of these scenarios? Table 2.1 summarizes the impact on your investment for a range of down payments under each case. Four rows are highlighted to demonstrate the impact of debt: 10 percent down, 20 percent down, 50 percent down, and 100 percent payment in full.

Table 2.1. Debt's Amplification Power

Initial | Initial | Happy Times | Sad Times | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Value | % down | Equity | Value | Debt | Equity | Return | Value | Debt | Equity | Return |

$100 | 0% | $0 | $110 | $100 | $10 | Infinite | $90 | $100 | ($10) | Infinite |

$100 | 10% | $10 | $110 | $90 | $20 | 100% | $90 | $90 | 0 | (100%) |

$100 | 20% | $20 | $110 | $80 | $30 | 50% | $90 | $80 | $10 | (50%) |

$100 | 30% | $30 | $110 | $70 | $40 | 33% | $90 | $70 | $20 | (33%) |

$100 | 40% | $40 | $110 | $60 | $50 | 25% | $90 | $60 | $30 | (25%) |

$100 | 50% | $50 | $110 | $50 | $60 | 20% | $90 | $50 | $40 | (20%) |

$100 | 60% | $60 | $110 | $40 | $70 | 17% | $90 | $40 | $50 | (17%) |

$100 | 70% | $70 | $110 | $30 | $80 | 14% | $90 | $30 | $60 | (14%) |

$100 | 80% | $80 | $110 | $20 | $90 | 13% | $90 | $20 | $70 | (13%) |

$100 | 90% | $90 | $110 | $10 | $100 | 11% | $90 | $10 | $80 | (11%) |

$100 | 100% | $100 | $110 | $0 | $110 | 10% | $90 | $0 | $90 | (10%) |

In the scenario in which you do not borrow any money and pay for your house with $100 (i.e., 100 percent down), your investment return in each case is equal to the change in the asset value (i.e., +10 percent in home value = +10 percent in equity value). As the amount of debt utilized increases, however, the return on your invested capital is a multiple of the return. For instance, if you purchased your home with $50 down and a $50 mortgage, then a 10 percent move in the house price equated to a 20 percent move in your equity value. Likewise, with 20 percent down, a 10 percent move in the house price equates to a 50 percent move in your equity value. In each of these cases, the return on your equity is equal to a multiple of the return on the house. More precisely, the equity return is equal to

Return of asset × (1 / % Down)

In sum, debt amplifies your returns—you make more money when asset values rise, and you lose more money when asset values fall. Given the powerful amplification feature of debt, it should come as no surprise that some of the most persuasive arguments explaining boom and bust cycles are based on debt and debt cycles.

To understand debt dynamics in a more granular way, let us look at three different families: the Safe Smiths, the Optimistic Osbornes, and the Carefree Carrolls.[50] As you meet each of these families, pay attention to their risk profiles and how each fares under Happy Times and Sad Times. Here are some facts that apply to all three families:

All houses cost $100

Each family earns $25 per year before taxes ($15 after taxes)

Each family has nonmortgage expenses of $10 per year

Money available for mortgage payments each year is therefore $5

All mortgages are obtained from Local Bank ABC, must be refinanced or paid off at the end of five years, and are available with the terms shown in Table 2.2 thanks to a government program guaranteeing access to home purchase finance

The Safe Smiths are a conservative bunch. Mr. and Mrs. Smith both work and the family lives within its means. Like all other families in the neighborhood, the Safe Smiths purchased a home this year for $100. Although they have savings in excess of $100, they decided to purchase the home with $40 down and a $60 mortgage. Because they put 40 percent down and their mortgage amount is less than $100, the rate that they obtained for their mortgage was 4 percent. Their yearly interest payments to the bank are therefore $2.40, and if they are interested in paying off their mortgage in 30 years, their annual payment (i.e., principal and interest) is equal to $3.44. Given they have $5 available for mortgage payments, the Safe Smiths sleep well at night and are not worried about their budget.

Table 2.2. Local Bank ABC Loan Rates

Loan Amount | ||

|---|---|---|

Down Payment | <$100 | $100 + |

0% | 7.00% | 7.50% |

10% | 6.25% | 6.75% |

20% | 5.50% | 6.00% |

30% | 4.75% | 5.25% |

40% | 4.00% | 4.50% |

50% | 3.25% | 3.75% |

The Optimistic Osbornes are a bit more aggressive. They believe the future is bright, and are willing to plan on a better tomorrow. They haven't saved as much as the Safe Smiths, but have enough capital for a 20 percent down payment. Thus, they take out an $80 mortgage and the bank gives them a mortgage rate of 5.5 percent. Their yearly interest payments to the bank are $4.40, and if they are interested in paying off their mortgage in 30 years, their monthly payment is equal to $5.45. Like all other families in the neighborhood, the Optimistic Osbornes only have $5 available for mortgage payments, so they opt for an "interest only" mortgage and agree to pay the $4.40 per year. The family is optimistic that Mr. Osborne may get a promotion (with an accompanying increase in salary) or that the house will appreciate in the near future. Even if they cannot begin paying the full $5.45 per year, the Osborne family is confident that they can refinance the house once it has appreciated and get a lower interest rate on their mortgage.

Finally, the Carefree Carrolls are an optimistic lot who live solely in the present. They don't think about the future and believe tomorrow is always better than today, that house prices always go up, and that budgeting is a worthless task. The Carefree Carrolls love to consume and have not saved very much over the years. As a result, they have no money for a down payment and must seek $100 of financing. Thanks to government programs encouraging homeownership, they are able to get the mortgage at a rate of 7.5 percent, with a flexible payment schedule. For the first three years of ownership, they are allowed to pay what they are able and any unpaid interest will be added to the principal of the loan. Their yearly interest payments to the bank are $7.50, and if they are interested in paying off their mortgage in 30 years, their annual payment is equal to $8.39. Given they only have $5 available for mortgage payments, the bank has arranged to let the Carefree Carrolls pay $5 and let $2.50 be added to the balance of the mortgage at the end of the year. The family is ecstatic they're able to buy their new home and, given the stories they've heard of people making money in real estate, are looking forward to real estate riches.

Table 2.3 summarizes the financial obligation structures for these three families.

Table 2.3. Comparing the Safe Smiths, Optimistic Osbornes, and Carefree Carrolls

Safe Smiths | Optimistic Osbornes | Carefree Carrolls | |

|---|---|---|---|

Purchase Price | $100 | $100 | $100 |

Down Payment | $40 | $20 | $0 |

Mortgage | $60 | $80 | $100 |

Interest Rate | 4.0% | 5.5% | 7.5% |

Payments | |||

Interest | $2.40 | $4.40 | $7.50 |

Principal + Interest | $3.44 | $5.45 | $8.39 |

To see how each family does in Happy Times and Sad Times, look at their financial conditions at the end of year one. To simplify the analysis, let's assume that each family pays the entire $5 to the bank in year one, meaning that the Safe Smiths pay $2.40 in interest and the remaining $2.60 as principal repayment to the bank. Likewise, the Optimistic Osbornes pay $4.40 in interest and $0.60 as principal. The Carefree Carrolls will pay $5 towards interest, and borrow an additional $2.50 to pay interest. Table 2.4 summarizes each family's equity return after one year in both Happy Times and Sad Times.

Let us now consider two new scenarios, Very Happy Times and Very Sad Times, in which house prices rise and fall, respectively, by 25 percent over five years. How do each of the families fare? Again, for simplicity, let's assume that each family pays only interest for the five years and applies all saved money (i.e., annual savings = $5 minus the interest payment) to principal at the end of the five years. Table 2.5 summarizes the resulting outcomes for the families in both Very Happy Times and Very Sad Times.

Given that each party has a mortgage balance at the end of the five years and must refinance the loan, let's examine the how each family's down payment (i.e., the equity value) changed as a percentage of the home value, and the new resulting interest rate.

For the Safe Smiths, neither Very Happy Times nor Very Sad Times greatly affect their refinancing terms. In Very Happy Times, they can refinance at a rate of 3.25 percent because their down payment is now effectively >50 percent. In very sad times, they can refinance for 4.75 percent with their yearly interest payment due as $2.23, still comfortably below their $5 budget.

Table 2.4. Happy Times and Sad Times

Safe Smiths | Optimistic Osbornes | Carefree Carrolls | |

|---|---|---|---|

Happy Times | |||

House Value | $110.00 | $110.00 | $110.00 |

Mortgage | $57.40 | $79.60 | $102.50 |

Equity Value | $52.60 | $30.40 | $7.50 |

Original Equity | $40 | $20 | $0 |

Return | 31.5% | 52.0% | infinite |

Sad Times | |||

House Value | $90.00 | $90.00 | $90.00 |

Mortgage | $57.40 | $79.60 | $102.50 |

Equity Value | $32.60 | $10.40 | ($12.50) |

Original Equity | $40 | $20 | $0 |

Return | −18.5% | −48.0% | infinite |

Table 2.5. Very Happy Times and Very Sad Times

Safe Smiths | Optimistic Osbornes | Carefree Carrolls | |

|---|---|---|---|

Very Happy Times | |||

House Value | $125.00 | $125.00 | $125.00 |

Mortgage | $47.00 | $77.00 | $112.50 |

Equity Value | $78.00 | $48.00 | $12.50 |

Original Equity | $40 | $20 | $0 |

Return | 95.0% | 140.0% | infinite |

Very Sad Times | |||

House Value | $75.00 | $75.00 | $75.00 |

Mortgage | $47.00 | $77.00 | $112.50 |

Equity Value | $28.00 | ($2.00) | ($37.50) |

Original Equity | $40 | $20 | $0 |

Return | −30.0% | −110.0% | infinite |

The Optimistic Osbornes, however, are greatly affected by the difference between Very Happy Times and Very Sad Times. In Very Happy Times, they're able to refinance to 4.75 percent (because their down payment is effectively 38 percent), leaving them with an interest payment of $3.88 and interest + principal payment scheme of $4.80 for a 30-year payoff (both of which are within their $5 budget). In Very Sad Times, however, they must refinance at a rate of 7 percent, leaving them with interest payments of $5.39—meaning they must borrow more each year simply to make the payments.

For the Carefree Carrolls, Very Happy Times allow them to continue their lives effectively "as is." They're able to refinance at a lower rate of 6.75 percent, but due to the extra money they've borrowed over the years, their yearly interest payment ($7.59) remains in excess of their $5 budget. Very Sad Times, however, are very sad indeed for the Carefree Carrolls. Because they have a loan amount that is far in excess of the house's value, the bank is not willing to refinance the property and instead forecloses.

As these examples have shown, the relationship between debt, collateral (i.e., down payment or equity amount), and asset prices has the potential to create a toxic cocktail that can greatly improve or deteriorate one's financial condition quite rapidly. The next section turns to a theory—the Financial Instability Hypothesis—that suggests these relationships result in a cyclical flow of credit that results in continuous financial instability.

Hyman Minsky was an American economist and professor of economics at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. A graduate of the University of Chicago and Harvard University (where he studied under Joseph Schumpeter and Wassily Leontief), Minsky was a relatively unacknowledged economist until after his death in 1996. "With long, wild, white hair, Minsky was closer to counterculture than to mainstream economics."[51] Although his initial research was focused on poverty, he was taken by a seemingly simple question: Could the Great Depression happen again?[52] It was from this line of research that Minsky delved into the topic of financial crises and debt dynamics preceding, during, and subsequent to them. The outcome of this effort was the Financial Instability Hypothesis.

Recently, Minsky's theories have found a home among practicing financiers. In fact, UBS held a conference call in October 2009 titled "Minsky for Beginners" for their institutional clients. During the call, George Magnus, former UBS chief economist, eloquently summarized the Financial Instability Hypothesis:

Minsky's big contribution was the proposition that after long periods of economic stability, endogenous destabilizing forces in the economy begin to develop, forces that eventually lead to financial instability... [H]e argued that this happens through the progressively more interesting but then progressively more dangerous use of leverage.[53]

The roots of this internally produced instability, Minsky argues, are found in the three primary forms of debt structures that exist in a capitalist society, and their relative predominance in the system at various points in time. His three distinct income-debt relationships were labeled according to their respective ability (or inability) to pay interest and principal from normal cash flows as hedge, speculative, and Ponzi.[54]

Hedge financing takes place when one is able to pay back both the interest owed as well as the principal due via normal cash flows. This approach is not particularly risky and is not subject to changing market conditions. The Safe Smiths in our preceding examples can be classified as hedge financiers.

Speculative financing is a bit riskier because it is an approach in which interest expenses are paid, but the principal must be refinanced upon maturity. According to Minsky, "the speculation is that refinancing will be available when needed."[55] Greater risk is borne as the availability of debt for refinancing may be available at materially different prices than originally envisioned. The Optimistic Osbornes began as speculative financiers.

Finally, Ponzi financing takes place when one is dependent on the availability of additional debt in order to pay interest on existing debt. Given the inability to pay interest expense out of cash flows, the possibility of principal paydown is nonexistent in Ponzi financing structures. This structure is based on an operating assumption that values will continually rise, allowing for easier and more advantageous refinancing terms. The Carefree Carrolls are Ponzi financiers. Table 2.6 summarizes these three financing structures.

The Financial Instability Hypothesis that Minsky proposes is based on a shift in the mix of financing structures present in a society. In a working paper presented at Bard College, Minsky eloquently summarized his theory, utilizing the language of equilibrium presented in the prior chapter:

Table 2.6. Minsky's Debt Descriptions

Hedge | Speculative | Ponzi | |

|---|---|---|---|

Cash Flow Adequate to Pay Interest? | Yes | Yes | No, interest must be paid for with new debt |

Cash Flow Adequate to Pay Principal? | Yes | No, principal must be refinanced with new debt | No, principal must be refinanced with new debt |

It can be shown that if hedge financing dominates, then the economy may well be an equilibrium-seeking and -containing system. In contrast, the greater the weight of Ponzi finance, the greater the likelihood that the economy is a deviation-amplifying system.[56]

Shifting economic conditions further complicate the distinctions of these financing structures, as hedge units could become speculative units or Ponzi units, and speculative units may well turn into Ponzi units in environments of degrading profitability.

Earlier, we observed a shift in the type of financing structure utilized by the Optimistic Osbornes depending on the state of asset prices. In Very Happy Times, the Optimistic Osbornes migrated from speculative financiers to hedge financiers. However, in Very Sad Times, they morphed from speculative to Ponzi financiers.

Minsky's argument about constant instability is straightforward: "Over a protracted period of good times, capitalist economies tend to move from a financial structure dominated by hedge finance units to a structure in which there is a large weight of units engaged in speculative and Ponzi finance."[57] Thus, in a self-fulfilling, reflexive manner, financing units get more and more aggressive as the lack of failure justifies this tendency. Eventually, however, the weight becomes unbearable and the structure implodes. This procyclical tendency of credit to grow in riskiness during good times is very destabilizing, and something I call the Minsky Migration.

McCulley eloquently summarizes Minsky's underlying point: "Put differently, stability can never be a destination, only a journey to instability."[58] McCulley coined the term the "Minsky Moment," representing that moment in time when the credit structure switches from getting more aggressive to less aggressive. After the Minsky Migration crosses the Minsky Moment, bad things happen. Speculative and Ponzi units begin to implode, and hedge units become vulnerable as the entire economy wobbles. Asset prices plunge as those units unable to obtain refinancing are forced to sell assets. This dynamic, which causes broad and great pain in an economy, is known as debt deflation.

Irving Fisher[59] is most known for his unfortunately timed statement in 1929, days before the stock market crash, that "stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau." His insistence immediately after the crash and up until the economic contraction had acquired significant momentum that stock prices were destined to go higher, combined with the failure of a firm he started, led most people to dismiss him and his ideas entirely. His debt-deflation theory, in which he argued that deflation increased the real value of debts, did not receive serious attention until well after his death.

Although Fisher was a devout believer in general equilibrium theory prior to the Great Depression, he quickly rejected the idea of a stable equilibrium by 1933, noting that "there may be an equilibrium which, though stable, is so delicately poised that, after departure from it beyond certain limits, instability ensues, just as, at first, a stick may bend under strain, ready all the time to bend back, until a certain point is reached, when it breaks."[60] In fact, Fisher stated that he believed the concept of equilibrium to be "absurd" and that "at most times there must be over- or under-production, over- or under-consumption, over- or under-spending, over- or under-saving, over- or under-investment, and over- or under- everything else."[61]

Once the Great Depression was in full force, Fisher developed a cycle theory of booms and busts: the debt-deflation theory of great depressions. Embodied in his book Booms and Depressions and succinctly summarized in a 1933 Econometrica journal article, the theory is based on the premise that overindebtedness and deflation are a toxic combination, regardless of other factors that may be present. Fisher admitted that overinvestment, overconfidence, and overspeculation were important considerations, but further noted that "they would have far less serious results were they not conducted with borrowed money."[62]

At the root of the debt-deflation theory is an understanding that falling prices effectively increase the real value of debts, further burdening already stressed borrowers like the Osbornes and the Carrolls. This process usually results in forced and uneconomic selling of assets by overindebted companies and individuals, which results in further falling prices that results in an effective increase in real debt. Fisher summarizes the results of this process: "when overindebtedness is so great as to depress prices faster than liquidation, the mass effort to get out of debt sinks us more deeply into debt."[63]

Many scholars today argue that the twentieth century had experienced two serious bouts of debt deflation: the Great Depression and Japan's Lost Decade(s). Because data is significantly more available for the Japan case, recent (and ongoing) research on the Japan case has proven additive. In particular, Richard Koo's formulation of a two-stage business cycle is worth considering. In the normal course, notes Koo, businesses focus on profit maximization as is suggested by traditional economic theories. Following a highly leveraged boom, however, the power of debt-deflation dynamics drives companies to focus on deleveraging—even if at the expense of profit maximization. The result is a lack of demand for credit, and, as he observed in Japan, constant deleveraging despite interest rates of close to 0 percent.[64] This part of the business cycle is one that Koo labels a "balance sheet" recession.

The debt-deflation theory to some extent mixes the dynamics of leverage with reflexive tendencies. That is, selling begets more selling, and the self-fulfilling fear of lower prices is amplified by leverage. Debt-deflation theories emphasize what occurs after a bust—inadequate demand driving deflation, which becomes particularly toxic when compounded with debt. The next section describes the Austrian business cycle theory, a similar theory (different in its emphasis on events prior to the bust) suggesting that overinvestment and excess capacity create the bust.

The Austrian School of Economics[65] uses the banking function of connecting savers with borrowers as the basis upon which it builds a theory of boom and bust cycles. At its root, the theory posits that excessive credit growth (driven by government intervention via interest rate policies, etc.) is the root of speculative booms and busts by generating unsustainable growth. The underlying belief is that "there is an economic and moral difference between legitimate ownership that comes from deferred consumption and premature ownership that is subsidized by the monetary system."[66]

The Austrian business cycle theory is similar in many respects to Minsky's financial instability hypothesis. According to the theory, artificially low interest rates result in bad investments and overconsumption, creating excess capacity and motivating businesses and individuals to under-save. Because central banks monopolize money creation (see box on Fractional Reserve Banking and Money Creation) and therefore affect the credit cycle, Austrian economists suggest that central banks lie at the origin of financial bubbles.

The Austrian school has three underlying beliefs that are particularly pertinent to our discussion of booms and busts: (1) equilbrium is a nonsensical construct, (2) aggregation is not possible, and (3) interest rates help determine preferences for consumption today vs. consumption in the future.[67] To begin, they reject the idea of equilibrium. Noble-prize winning Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek succinctly captured the perspective that equilibrium is the exception by stating "before we can even ask how things might go wrong, we must first explain how they could ever go right."[68]

Another Austrian tenet is that aggregates are nonsensical constructs because individuals have unique tastes and time horizons that cannot be summed into singular demand curves. Llewellyn Rockwell, founder of the Ludwig von Mises Institute, eloquently captures the spirit of this second point by noting that "every actor in the economy has a different set of values and preferences, different needs and desires, and different time schedules for the goals he intends to reach."[69]

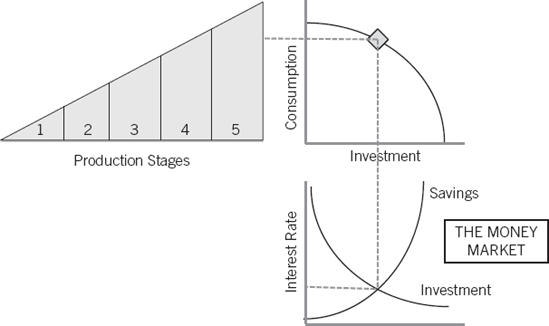

Though there are many ways of interpreting this belief, the most popularized manner[70] of presenting the heterogeneity of capital decisions (the most relevant for our boom–bust focus) is the stages of production triangle, also known as the Hayekian triangle in honor of Hayek. Figure 2.1 presents a simplified version of it with five production stages.

Examples of production stages that might be early (i.e., stage 1) include basic research and development and other capital allocation decisions that might be years from impacting a firm's bottom line. These earlier stages are truly "investment" stages in which today's profits are foregone in return for the expectation of future profits. Likewise, examples of late-stage production functions include inventory and working capital management. These are production functions that are temporally proximate to consumption.

Because the dynamics that affect capital allocation decisions in early stages differ from the dynamics affecting later stages, Austrians believe that a simple aggregation is inappropriate. The slope of the triangle's hypotenuse can be thought of as an indicator of the interest rate. Steep triangles imply high interest rates, and a corresponding minimization of long-run (i.e., stage 1) investments. Flat triangles imply low interest rates with corresponding emphasis on long-run investments. In many ways, the slope can be thought of as a proxy for the time value of money and therefore the hurdle rate for investment decisions.

The third Austrian belief of relevance to us is that consumption and investment trade off against each other (unlike the traditional economic interpretation that economic output is the result of consumption plus investment plus government spending plus net exports). Thus, investment is defined as foregone consumption, and likewise, consumption is foregone investment. Given that this consumption vs. investment framework necessitates a trade-off between the suppliers of funds and the demanders of funds, we are effectively talking about the market for money. The clearing price of the money is the interest rate.

Market-clearing interest rates, note the Austrians, allow for the optimal allocation of resources between consumption and investment. The following diagram summarizes how the interest rate (i.e., the price of money that allows the supply of saving and the demand for investment capital to be matched) drives the trade-off on the consumption/investment frontier. The various stages of production then align with the consumption for an appropriate allocation of corporate resources. Figure 2.2 summarizes these relationships.

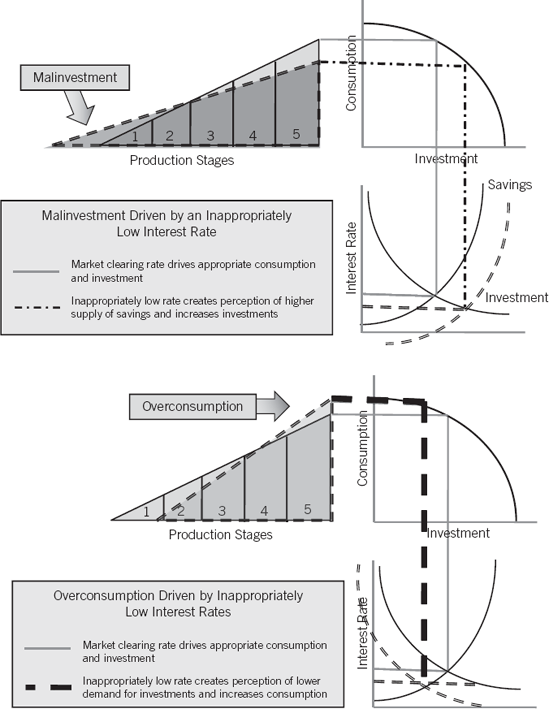

The involvement of central banks in setting the price of money is confusing and causes problems, assert the Austrians. Central banks in democratic capitalist societies[71] are motivated to keep interest rates below their appropriate level, and the result on investment decisions is an inappropriate increase in long-run investments. By long-run, we are describing capital investments that do not provide a payback for a significant period of time. Research and development, plant expansions, and the like would be good examples of long-run investments. Increasing a sales force might be considered a short-run investment.

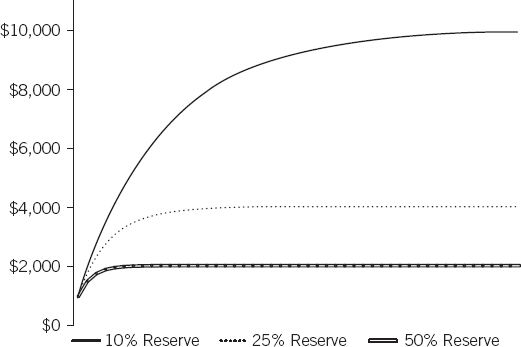

From the perspective of the corporate entity making investment decisions, it appears that the savings are greater than they in fact are. This distorted perspective arises due to the primary mechanism through which central banks manipulate interest rates—management of the money supply. To reduce interest rates, central banks can "manufacture" money by either lowering the interest rate by mandate or lowering required reserve ratios.

Likewise, inappropriately low interest rates cause consumption to be higher than would be the case with an appropriate rate. From the perspective of the saver, it appears that there is less demand for capital than is actually the case. With a lower opportunity cost for consuming, entities choose to consume at a level above one that would naturally occur at an appropriate interest rate. The result of this higher consumption is that corporate investment decisions are shifted increasingly toward short-run production stages. Because demand is robust, inventories are built, and so on. Figure 2.3 summarizes how inappropriately low rates result in both malinvestment (top half) and overconsumption (bottom half).[72]

Eventually, bad investments and/or overconsumption must be addressed and an overly "consumed" society is found with too much debt (due to the low cost of money) and a need to increase savings. At this point, the bust portion of the cycle begins as savings increase (either via actual savings or via debt repayment), consumption slows, and profit maximization is deemed subservient to balance sheet repair typical of Koo's balance sheet recessions.[73] Significant excess capacity from overinvestment results in deflationary forces, which increases the real value of debt. Austrians believe that this process must be free to run its course, independent of bailouts and other government intervention, in order to purge the system.

As is clear from the above diagrams and descriptions of the relationships that result in malinvestment and overconsumption, Austrians believe the root cause of the boom–bust cycle is inappropriately low interest rates. One mechanism through which central banks such as the Federal Reserve control interest rates is via deposits held at their member banks. So, the Federal Reserve creates money and then deposits it into banks. Through the money multiplier effect described above, these deposits are multiplied as banks lend capital to those seeking it. Simple supply and demand dynamics (i.e., more supply) drive the cost of money (i.e., the interest rate) down as a result of the money-creation process. The unlimited capability of the Federal Reserve's "printing press," combined with the multiplicative power of fractional reserve banking, enables the Fed to effectively set short-term interest rates.[74]

Austrians note the inherent contradiction of economists who claim the "market knows best" working at the Fed. In many ways, the Federal Reserve operates as a central planning organization more typically found in communist/socialist societies.[75] Austrians believe knowledge is inherently difficult to obtain (not unlike Soros's belief regarding social science) and that any intervention into markets is inherently distortive. This belief regarding the U.S. central bank is perhaps best captured by U.S. congressman and 2008 presidential candidate Ron Paul, who notes: "After decades of experience in grappling with Fed officials in committee meetings and of lunches and private discussions with Fed chairmen, a lifetime of reading serious economic literature, and a profound awareness of the dangers to liberty in our time, I know there is absolutely no hope for the Fed to conduct responsible monetary policy."[76]

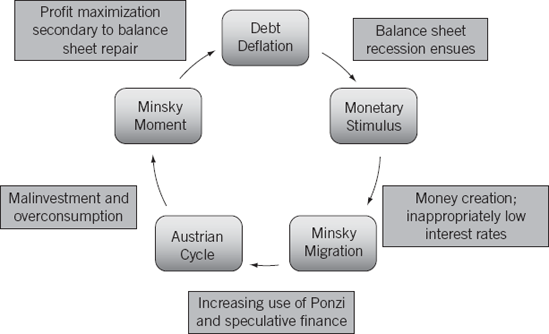

Although some of the lenses presented in this Chapter are not fully-accepted by economists, they provide powerful tools through which to recognize, evaluate, and understand booms and busts. Further, despite their seemingly disparate foci, the Austrian cycle, Financial Instability Hypothesis, and debt-deflation theory can be integrated into one coherent theoretical construct.

Figure 2.4 notes the interaction of these components into an integrated macroeconomic lens for the evaluation of financial extremes. As shown by the circular flow, the cyclical nature of debt is at the heart of the framework, with debt and its magnifying power as the primary drivers of the cycle.

As we turn to the next chapter, the focus of our lens-building efforts turns to psychology and the cognitive biases that often affect human decision-making processes.