11 Pay policy, pay processes, and the management of rewards

11.1 Introduction

Reward management encompasses both extrinsic rewards, of which pay is the most important, and intrinsic rewards such as recognition and status. This chapter concentrates on pay policy and pay processes, whilst bearing in mind that pay has to be treated as part of the total employment package in the manner highlighted in .

Pay represents both a cost and an investment to the organisation. It is the largest cost item for many employers. Attention to budgeting and control is always important. Pay is also an investment because it represents money spent in pursuit of productivity. Ensuring that the money devoted to pay is invested wisely is the prime objective of a company’s pay policy. Economic conditions have in recent years forced organisations to become leaner, fitter and more customer-oriented and this has been reflected in their pay structures. Pay policy aims to facilitate the attraction and retention of employees and to encourage effort and cooperation as well as a willingness to learn new skills and to adapt to change. At the same time, pay policy has to be administered in a manner perceived by employees to be equitable and fair.

In this chapter methods of updating policies on pay and developing rewards appropriate to organisational goals and strategy are examined. While the administration of pay has become increasingly specialised in larger organisations, pay policy is too important to be left to the specialists. Corporate strategy must provide the overall direction, with line management involved in all stages of its operation and the HRM function providing advice and support.

11.2 Market forces

Any review of pay policy must start with economic considerations: there are limits as to what organisations can afford to pay, and the objective must be to make pay increases self-financing through higher productivity. The basic price of labour in a free economy is determined largely by the forces of supply and demand in the labour market and no organisation can afford to let itself be too far out of line. Pay policy has to be incorporated into budgets which in their turn require accurate forecasts of trends in external pay levels. Employment costs consist of more than basic wages, and include pension contributions, holiday pay, sickness benefits, and a range of other benefits outlined below.

A number of sources of intelligence are available concerning the labour market. Systematic investigation is essential if the correct conclusions are to be drawn since haphazard and ‘off the cuff’ investigations are liable to mislead. Job titles can mislead, so accurate job descriptions are vital. The five factors of skill, responsibility, mental effort, physical effort and working conditions provide a popular and well-tried set of headings for this purpose. Systematic investigations into pay levels frequently concentrate on so-called ‘benchmark’ jobs. These are jobs considered to have special significance for pay structure on account of custom and practice, their use in pay bargaining, and the number of employees covered.

Useful sources of information on market rates include:

• information gleaned from job applicants;

• job advertisements in papers and journals, although these should be treated with caution as they can mislead, and may not be based on accurate job descriptions;

• private employment agencies who are usually helpful, but have a vested interest in inflating rates;

• public employment agencies, such as ‘Job Centres’;

• published surveys: although publishers may charge a high fee to cover costs, reputable publications such as Incomes Data Services provide excellent information;

• official publications such as the Labour Market Trends provide general information but are of limited use for local labour market information;

• inter-firm pay surveys can be an excellent source of information.

Regular inter-firm pay surveys are carried out by a large number of organisations.

11.3 Pay surveys

The financial rewards offered by most organisations embrace a complete package of basic pay plus a variety of allowances, opportunities to earn overtime, and fringe benefits. Data generated on earnings should be in a format suitable for simple statistical analysis. A wide spread of earnings is frequently found within and across a sample of organisations. This information should be further simplified by calculating respective ranges, medians and quartile statistics. Management is then in a position to decide whether to maintain or establish a position as a relatively high, average, or low paying firm. The economic state of the organisation, the need to attract large numbers or a high class of recruit, the level of labour wastage, the trade union position, and the general employment philosophy of the organisation are all relevant considerations.

11.4 Job evaluation and internal equity

The concept of a fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work is deeply engrained into our thinking. A fair day’s pay tends to be defined by workers consciously or subconsciously by reference to what fellow workers in similar jobs are earning, particularly their colleagues at their place of work. While an internal structure of differentials is generally accepted as necessary by most workers, their feelings concerning equity and fairness demand that the size of differentials be regulated in accordance with some open and rational system. A professional approach to wage and salary administration by management likewise demands a rational and acceptable structure of differentials. These demands have given rise to the technique and widespread popularity of job evaluation.

Job evaluation is not a new technique. Most commonly found methods have been in use for the last 50 years. But in recent years there have been a number of attempts to adapt traditional methods to fit in with social and technological change, notably in the use of participation, consensus, information technology, and competencies. Exponents of job evaluation have sometimes claimed that it represents a truly scientific method of payment but this is an exaggeration. In the last resort, it can only rely upon subjective judgement. But there are many benefits that can accrue from a well-installed job evaluation scheme, including:

• cost control: where specific rates and differentials are established and maintained, labour costs can be analysed, budgeted, and controlled;

• fairness: employees can see that an impartial system is being used to establish differentials, and pay rates are not just subject to favouritism or whim;

• simplification: instead of a large number of different job rates, some perhaps only differing by a few pence, jobs can be slotted into a simple graded structure.

Job evaluation is essentially concerned with job content and not with either the individual job holder or outside market forces. In real life it is not always easy to ignore the job holder, who may in fact have had a large say in developing the scope of the job he or she occupies, nor the presence of supply and demand for particular job skills. However, management should aim for a practically useful scheme, acceptable to both management and workers, rather than one that is technically pure. The essence of job evaluation is job analysis. The successful operation of a scheme requires that thorough job studies are carried out by trained analysts. Also basic is the concept of ‘benchmark’ jobs — jobs accepted by all parties concerned as being fairly paid at the current time in relation to each other, and also having sufficient in common with the other jobs to be used for comparison. At the start of a job evaluation scheme considerable time needs to be spent on establishing satisfactory benchmark jobs. A method of checking on their usefulness is given under the points method outlined on page 186.

11.5 Traditional approaches to job evaluation

Different job evaluation techniques have their own peculiar advantages and disadvantages. Four techniques of job evaluation have been in use for many years. These are ‘ranking’, ‘grading’, ‘factor comparison’ and ‘points method’. The first two are based on ‘whole job’ comparison and are therefore referred to as ‘non-analytic’ to distinguish them from the latter two that analyse job content under a number of ‘factor’ headings.

Ranking

The object of ranking is simply to establish a rank order or hierarchy of jobs. Pay rates will then reflect this hierarchy. Evaluation is carried out by comparing the contents of jobs with the contents on the benchmark jobs, and putting the job into its appropriate place in the hierarchy. Evaluators must use their judgement as to whether one job is to be rated higher or lower than another job. In a typical engineering factory machine shop the following rank order might emerge: tool room fitter — maintenance fitter — machine setter — semi-skilled machinist — unskilled labourer. Rates of pay will then reflect this simple hierarchy, although the actual differentials must be settled by judgement or negotiation. The principal advantage of this method is its simplicity. It is easily understood, and is not complicated to carry out. But because it is so simple it is not appropriate when a large number of jobs of varied content need to be included. For example, we would have difficulty in fitting jobs such as ‘secretary’ or ‘sales representative’ into our rank order above but where a small homogeneous ‘family’ of jobs is concerned, ranking can be useful.

Grading

This technique is also referred to as ‘classification’. As its name implies, it is based on the establishment or maintenance of a graded, hierarchical, structure. Frequently a simple grading structure with a strictly limited number of grades is the objective. To take an example again from engineering, a company might have five basic job grades covering, in turn, highly skilled (apprenticeship plus further toolroom training), skilled (apprenticeship or equivalent), partly skilled (two years’ training), semi-skilled (four weeks’ minimum training) and unskilled work. These jobs are then fitted into a structure labelled grades A to E respectively, reflecting the differences in skill. Simplicity is the principal virtue of grading. It is extensively used in manufacturing industry and with white collar jobs. But as with ranking, it can only be effectively used within a homogeneous family of jobs of limited number.

Factor comparison

This method is less frequently used in practice. Jobs are compared on the basis of their relative importance under a set of job ‘factors’, such as ‘training’, ‘responsibility’, ‘skill’ and ‘physical effort’. A rank order is established under each of these headings, and the factors are then weighted in accordance with the opinions of the evaluating team. For example, under the factor heading of ‘physical effort’, our five engineering machine shop jobs might show up in the following rank order; semi-skilled machinist — machine setter — maintenance fitter — unskilled labourer — toolroom setter. The machinist should therefore be paid more under this factor heading than the toolmaker. The rank order will of course be different under other factor headings. Translating factor comparison into actual pay is something of a headache, and so the usual way out of the dilemma is to use a quantitative approach in which factors are accorded a points value, as in the points method.

Points method

Points method achieves a system of differentials by ranking jobs in accordance with the number of points they have been awarded during a job evaluation exercise. First, a set of factors must be drawn up that will permit satisfactory analysis and comparison of the jobs in question. A weighting exercise has then to be carried out to decide what possible maximum total of points shall be permitted under each factor heading. Illustrated by the application of a points scheme to the simple list of five jobs in a typical machine shop, and using the factors of training, responsibility, skill and physical effort, a weighting exercise for each factor might give a maximum of 20 points for each factor, giving a possible grand total of 100 points. The results of evaluation might then be presented as in Table 11.1.

Table 11.1 Job evaluation: simple points method scheme

If pay is directly related to points, it would mean in this case that toolroom setters earn four times as much per hour as labourers. As differentials of this order are not normally acceptable within a factory, this difficulty can be overcome by giving an initial allocation of 50 points to all jobs at the commencement of the exercise, giving a final differential between toolroom setters and labourers of 110:65. Thus, the toolroom setter earns £300 per 37-hour week the labourer earns £150.

This example highlights the fact that any job evaluation scheme must be tailored to individual company pay policy and practical objectives. The relationship between points and pence to be aimed for is normally a linear one with pay rising in proportion to the allocation of points. Such a points scheme can be portrayed on a graph. Graphs show up anomalies which it is the prime purpose of job evaluation schemes to correct. Figure 11.1 shows the results of an evaluation exercise which has allocated points totals to a number of jobs.

Figure 11.1 Job evaluation: a scattergram of points and money

Some of these jobs are in a correct relationship with each other and therefore fall on or near the straight line that relates points and money. A few jobs are some way from the line indicating that job holders are either being paid too much in relation to the agreed benchmark jobs (where they appear above the line) or are being paid too little (where they appear below the line). As will be seen in Figure 11.1, jobs A and B are being paid too much in relation to the points total credited to them, whereas jobs C and D are being paid too little. The remaining jobs are receiving the correct rate per hour. Strictly speaking, the pay for jobs A and B should be reduced, and that for C and D increased to bring them into line. In practice, individual rates of pay are usually only increased or maintained, never decreased. An undertaking to this effect is usually given in advance of the exercise to ensure the full cooperation of both employees and unions. Thus the rates for jobs A and B may be reduced to the appropriate level, but individuals currently occupying those jobs will be allowed to keep the higher rate, the difference between the newly adjusted rate and their own higher rate being expressed as a personal ‘plus’ rate in the pay records. These individuals may not share in annual cost of living or general increases until such time as the adjusted rate for the job has caught up with their hourly rate of pay, subject of course to negotiation and consultation. Frequently a job evaluation scheme is linked to a grading structure. A particular grade then includes all jobs that achieve a total of points falling within the minimum and maximum for that grade. Such a scheme is illustrated in Table 11.2, derived from a public sector job evaluation scheme.

Table 11.2 Job evaluation: an example of a points system and grade bandings structure

Grade 1 1000–1280 points

Grade 2 1281–1560 point5

Grade 3 1561–1840 points

Grade 4 1841–2120 points

Grade 5 2121–2400 points

Grade 6 2401–2680 points

Grade 7 2681–2960 point5

Grade 8 2961–3400 points

11.6 Modern forms of job evaluation

A variety of hybrid forms of job evaluation have been developed that place particular emphasis on certain aspects of job evaluation. For example, the so-called ‘consensus’ method places emphasis on achieving consensus amongst employees on the grades to be allocated. Some are named after the firm of management consultants that promulgate them. A well known example is the ‘Hay’ method. This method uses just three factors to evaluate jobs:

• knowhow;

• problem solving;

• accountability.

Each factor has further sub-factors. The Hay method is not a pure job evaluation technique because it also takes account of market forces. Companies which subscribe to the system have the benefit of an information service in market trends for jobs and an indication of what value should be attached to the points allocated to each job.

Some companies incorporate competencies into their job evaluation schemes, in order to recognise the importance of job competencies. This trend is examined in Chapter 12.

11.7 Introducing and maintaining job evaluation

The practical problems of choosing, introducing and maintaining a job evaluation scheme can exceed the technical problem of understanding and choosing the best method.1 Starting from scratch is an expensive business, because of the time required in analysing jobs and servicing consultative committees. Union consent may need to be gained and this can lead to tough bargaining. The official trade union line is not usually hostile to job evaluation, but trade unions not surprisingly demand adequate union representation on committees supervising the project. Naturally, union representatives may try to wrest maximum financial advantage for their members. Frequently job evaluation schemes are introduced as part of a package deal with unions when bargains are struck on related matters such as manning levels and pay increases. Once a scheme has been installed there is a dangerous temptation to assume it will continue to operate successfully for many years without much effort. But all job evaluation schemes decay over a period of time, as the organisation itself changes to meet new situations. Resources have to be made available to carry out regradings as job content changes.

11.8 Criticisms of job evaluation

In spite of its apparent advantages and rationality, job evaluation has been fiercely criticised and some companies have stopped using it.2 A major criticism used to be that it reinforced discrimination, particularly sexual discrimination, in the labour force. This was because heavier weighting seemed to be given to factors favouring men, such as strength or apprenticeship training, whereas factors covering such skills as dexterity or caring which featured in women’s work were lowly weighted. This situation has now been largely rectified. Job evaluation finds favour with industrial tribunals because it creates a payment system that is open to external inspection and correction.

The most serious criticism of job evaluation arises from its bureaucratic nature.3 Because it is based on job description, it assumes a degree of stability and hierarchy that is increasingly unrealistic in a world of rapid change. Organisations have to be flexible and responsive, and this means that staff must accept that their jobs are also susceptible to rapid change. Demarcation of jobs is a hindrance. Of late, market rates of pay have been held to be of greater significance than internal relativities by many employers. Modern forms of team working require different forms of payment.

11.9 Payment by results

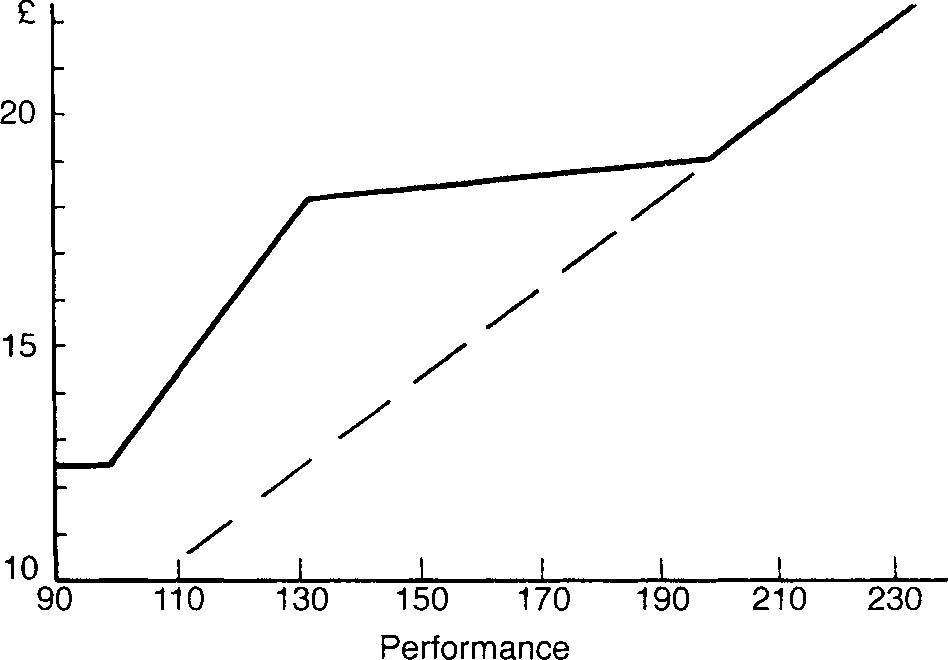

For the greater part of this century, ‘payment by results’ (PBR) has been the term given to pay schemes which link earnings to output and attempt to motivate workers, usually manual workers, to higher levels of productivity. The term reflects the tradition of distinguishing between pay schemes for manual (or blue collar) workers and office (or white collar) workers, hence the terms ‘wages’ and ‘salaries’. Traditionally, PBR has been seen as part of wage administration and the domain of work study engineers. Happily these status distinctions are being broken down, with the adoption of single status agreements. PBR systems remain widely used in industry — an estimated one-third of manual workers receiving some form of payment by results.4 But modern methods offer a considerable improvement on old-fashioned piecework techniques. Traditionally, PBR was payment by unit of output. Widespread introductions of time and method study led to systems based on time allowances, arrived at by using a range of techniques, from the simple stopwatch to complex synthetic data and Predetermined Motion Time Systems (PMTS). As part of this process ‘effort rating’ undertaken by time study engineers may help to achieve fair time allowances, i.e. a systematic estimate of the effort being put into jobs by workers to determine the time a worker of ‘effective worker standard’ (EWS) should take for job completion, making due allowances for fatigue, rest pauses, and unavoidable interruptions. This can then be converted into standard minute values (SMVs), enabling workers to be measured and paid according to a standard performance scale, such as the popular 60/80 scale, or the 0-100 (British Standards Institute) scale. These scales are based on the notion that workers on payment by results are likely to work faster than workers on a time rate, and should be rewarded accordingly. Thus with the 60/80 scale the timeworker is estimated to put in a ‘60’ performance, the PBR worker an ‘80’ performance (i.e. 1/3 higher). Target remuneration for a PBR worker should therefore be set correspondingly higher. PBR workers have the opportunity to earn considerably more than time workers, how much more depending on the system in use. The ILO defines four types of gearing of performance to pay, namely proportional, regressive, progressive, and variable. Under a ‘proportional’ system payment increases in the same proportion as output. A ‘regressive’ scheme means that payment increases proportionately less than output. Traditional schemes such as Bedaux, Halsey and Rowan fall in this category. Because payment per unit decreases as output rises, labour costs decrease as output increases, although the worker has to work harder to increase his income. Under a progressive scheme the reverse happens, i.e. payment increases proportionately more than output. Employees are thus encouraged to achieve higher levels of output, but management encounters problems of cost control. With variable systems, payment increases in proportions which differ at different levels of output, as illustrated by Figure 11.2.

Figure 11.2 Example of ‘variable’ payment by results system using BSI scale

Variable schemes may encourage higher output up to a certain level of performance, but can be complicated to install and difficult for employees to understand. Many firms operate PBR schemes which are based on ‘time rate plus’, i.e. workers are guaranteed a certain basic rate, and payment by results are then added to this. Frequently ‘fall-back’ rates also operate or other methods of guaranteeing earnings in the event of stoppages. ‘Lieu bonuses’ are often paid to certain categories of timeworkers, usually skilled workers such as maintenance craftsmen, to preserve differentials between them and production workers.

Group bonus and group PBR schemes operate along similar lines, but with the output targets set for groups of workers, e.g. on a production line. Bonus payments are then shared by members of the group. Such schemes may encourage group cooperation but discourage individual effort (examined further below).

Modified forms of PBR

In order to overcome some of the problems associated with traditional PBR systems, a number of modified schemes have been designed. Measured day work schemes, for example, determine the level of performance to be expected of an effective worker using work measurement techniques, and then fix an appropriate level of payment. Workers are expected to maintain this level of performance and to cooperate with management in return for guaranteed earnings and job security. Premium Payment Plan (PPP) is a graduated form of measured day work allowing workers some choice of performance level and the associated rate of pay. Under this system a worker can improve his or her pay in two ways — by achieving a higher level of performance over a specified period in the present job or by moving to a job in a higher classification.

Criticisms of PBR

As with all management systems, there are arguments both in favour and against, and once again we have to consider what is best in a particular situation. PBR can accentuate hostility between management and workers when PBR is seen as a management tool to extort more work out of workers, and when workers feel that work is being devalued to a series of hostile negotiations over money for effort. Added to this these are genuine problems of measuring effort and the risk that pressure for output will lead to poor quality work and a neglect of health and safety standards. PBR also provides opportunity for trade unions to demonstrate their support for their members by constantly arguing the toss over rates of pay, as well as providing an opportunity for workers to devote their energies to outwitting management and work study engineers rather than getting on with the job.

However, available evidence indicates that PBR can work where the scheme is well thought out, when working methods lend themselves to measurement, where industrial relations are good, and where high levels of communication and consultation take place before schemes are introduced. The introduction of PBR needs to be accompanied by support from managers at all levels, a relevant training and education programme, and a consultative approach. Evidence indicates that successful schemes have three main features in common:5

• They do not seek an immediate payback, but see PBR as part of an overall package of human resource initiatives designed to improve motivation and performance in the long term.

• Senior managers are committed to developing effective procedures.

• The objectives of the payment system are related to those of the organisation.

11.10 Gainsharing

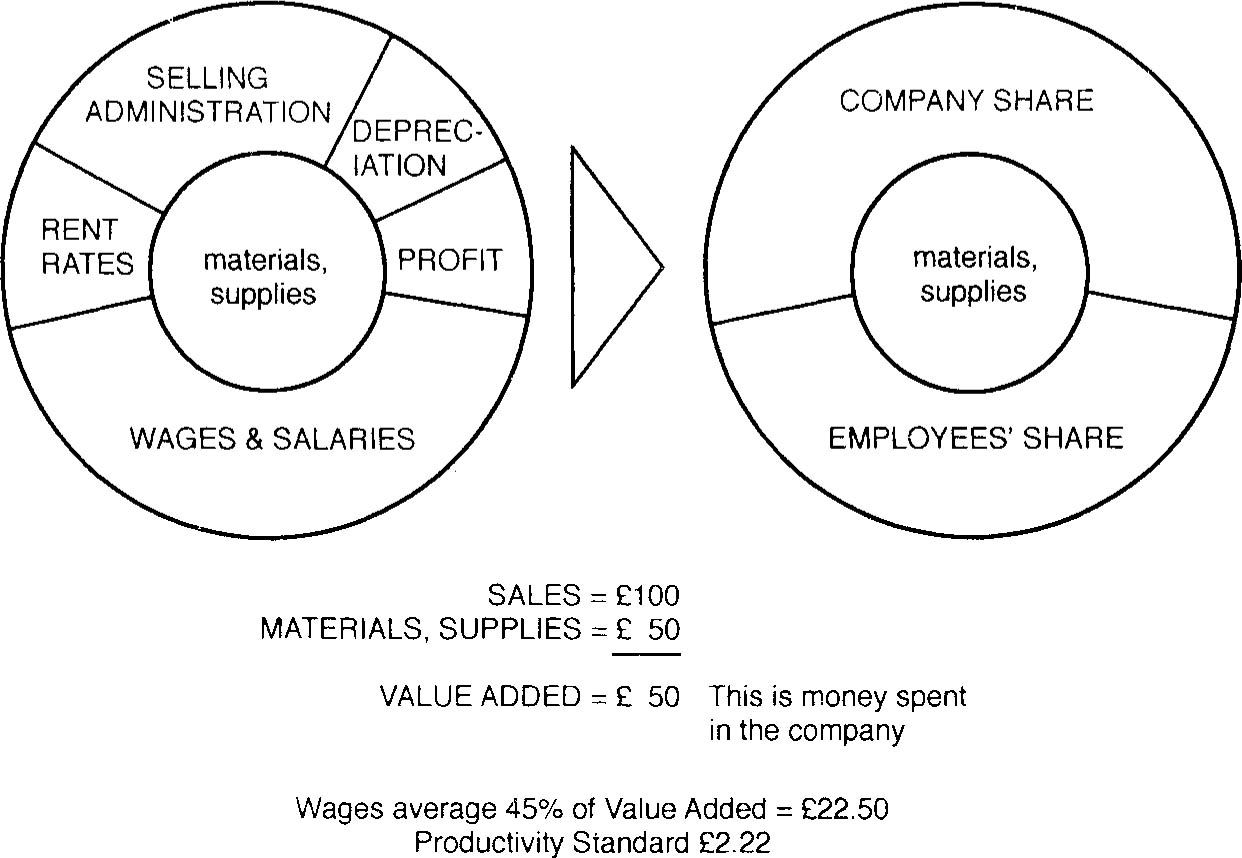

Gainsharing (also known as ‘value-added’) pay schemes have been adopted by employers who feel strongly that employees should see a connection between the contribution their efforts make to the prosperity of the enterprise, and the rewards they receive as a share of the value added to the product or service. Thus it is felt that employees can be encouraged to identify with the fruits of their labours and to participate in improving working methods. Such schemes require a high degree of commitment by management, a willingness to disclose information, good labour relations and careful measurement. Wages are an agreed proportion of the monetary sum derived by subtracting the cost of materials and other supplies, from sales revenue. A simplified version is illustrated in Figure 11.3.

Figure 11.3 Gainsharing: the value-added ‘doughnut’

The two best-known versions of value-added schemes are the Scanlon Plan and the Rucker Plan. The first, developed in the 1930s in the USA by Joe Scanlon (an ex-steel worker and union official who wished to see a sensible conclusion to the conflict between management and employees over pay levels), focused on the whole organisation, and involved unions and employees as well as management in productivity improvements. The Plan provides for 75 per cent of gains being distributed to employees with 25 per cent going to the firm. A similar idea was inherent in the Rucker Plan except that it modified the distribution to reflect the relative contributions of labour and capital in the particular organisation. A number of successful value-added schemes are currently in operation in the USA. Typically, the successful scheme shows productivity improvements of between 5 per cent and 15 per cent in the first year of operation together with an improvement in product quality. But there have been failures too, notably associated with bonus levels which fell short of employees’ expectations as well as inconsistencies in the treatment of different groups. A modified version of a value-added scheme has been in operation at Volvo’s plant at Kalmar, Sweden, where gains from productivity are shared between the company and employees, all of whom receive regular briefings from team representatives. In addition plant-wide assemblies take place twice each year.6

11.11 Salary structures

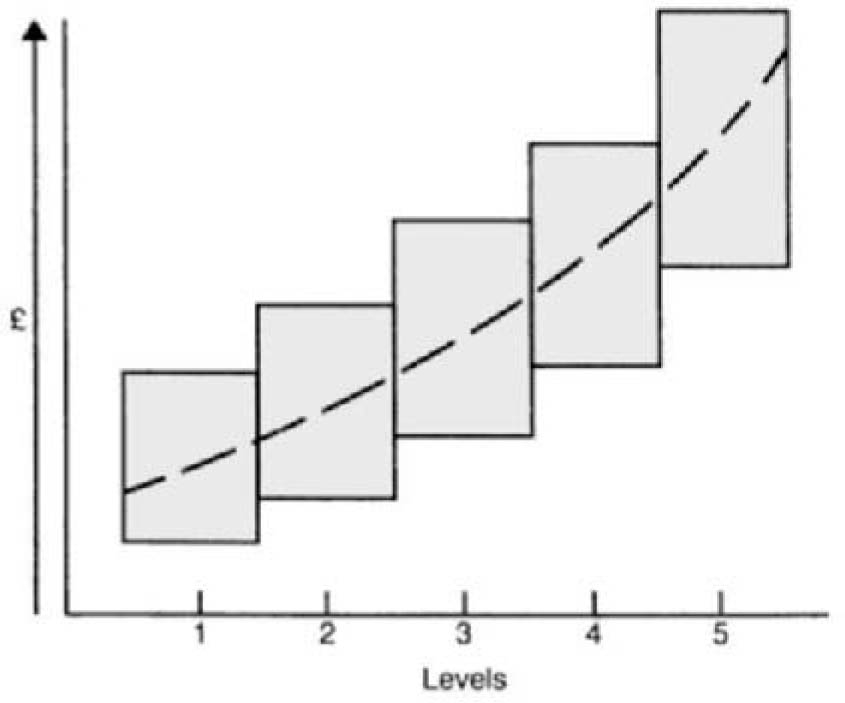

Salary structures composed of a range of pay grades and incremental scales within each of those grades are still widely used, despite recent trends to downsizing and delayering. A typical company structure is depicted in Figure 11.4.

Figure 11.4 Example of graded salary structure with varying overlap

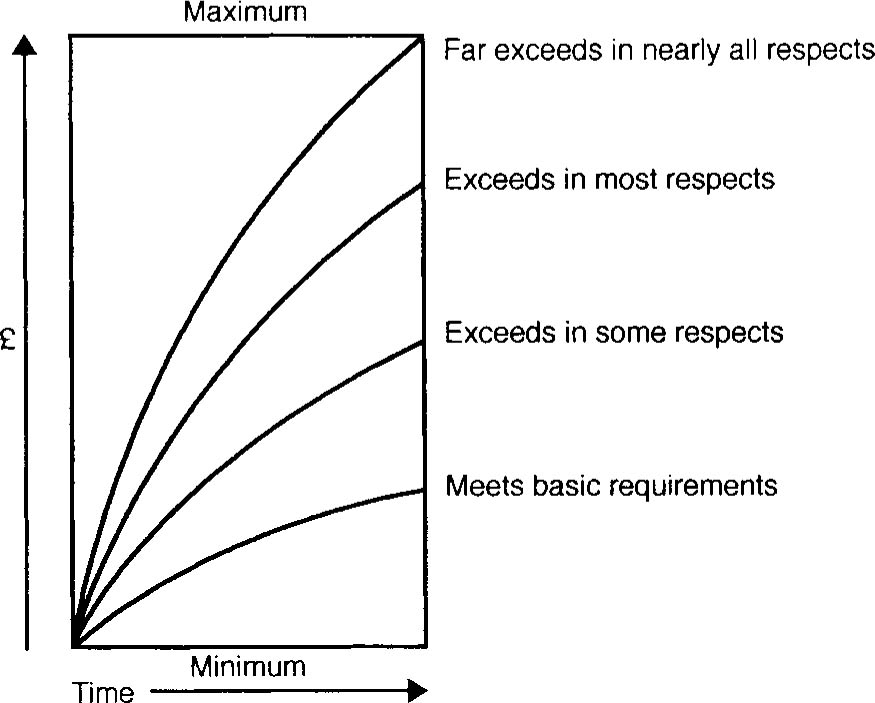

Three fundamental decisions in developing such a structure concern the number of pay grades, the range within each grade, and the amount of overlap between each grade. Structures incorporating a large number of grades, typically found in many public sector organisations, make promotion a relatively easy matter while devaluing the significance of promotion. Conversely, a structure with relatively few grades enhances the significance of promotion but decreases flexibility. Grades with a large measure of overlap devalue the financial significance of promotion but may lead to less pressure for promotion. Grades that embrace a wide range of pay permit a large number of incremental increases (usually justified on the grounds that experience and service deserve some reward) but can mean that two persons with different lengths of service doing the same job receive widely different rates of pay. It is possible to control progression through a pay grade in order to ensure higher rewards and faster progress for staff earning good appraisal reports. This is illustrated in Figure 11.5.

Figure 11.5 Salary grade relating progression to performance

A system of differential rewards can be taken one stage further by use of so-called ‘salary progression curves’. These curves depict the movement of employees’ salaries over a period of time, and can be viewed both as a historical process and a prediction for the future, as shown in Figure 11.6.

Figure 11.6 Salary progression curves

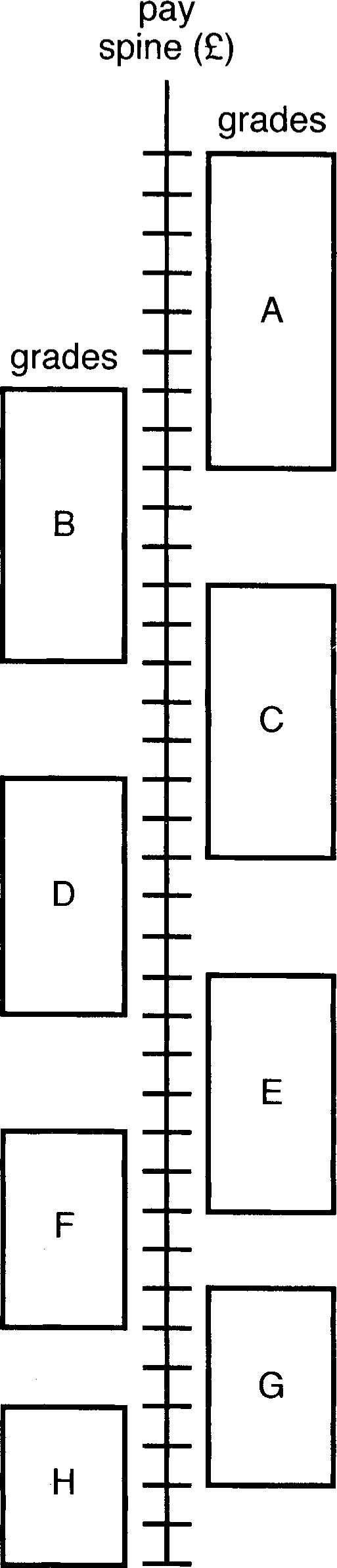

Unified pay structures are frequently used in the public sector, covering all sections of the workforce. Whilst similar to conventional large company pay structures depicted in Figure 11.5 above, they represent the values found in much of the public sector. A typical pay spine structure is depicted in Figure 11.7.

Figure 11.7 A typical pay spine

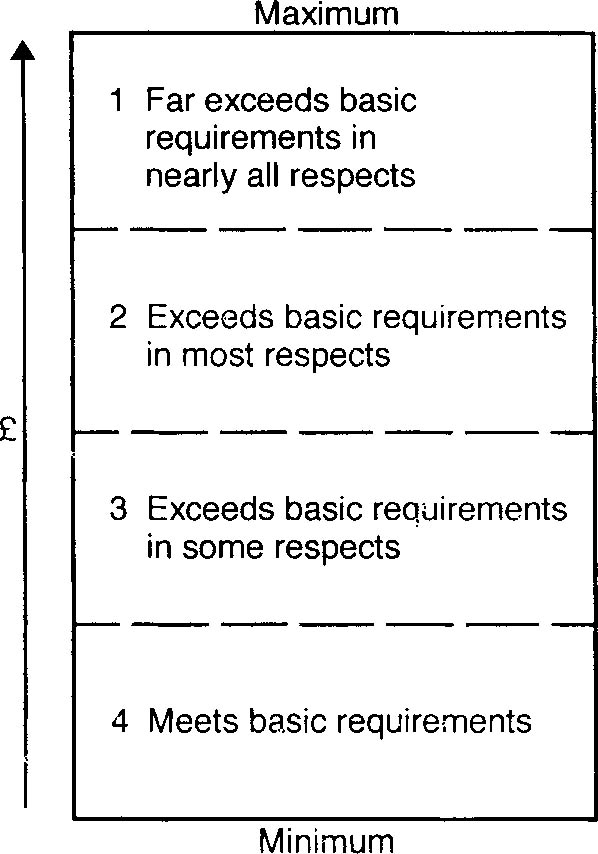

11.12 Merit awards

Merit awards for salaried staff attempt to reward higher levels of performance. Fewer pay schemes now award annual automatic cost of living increases to all employees; instead, any pay increases are referred to as ‘merit awards’ and some employees receive no increase. These may be linked to some form of appraisal (examined in Chapter 12).

The evidence in favour of such merit awards is not clear-cut: while in theory they should stimulate greater effort, in practice, they can run into a number of practical problems. Staff may not be convinced that the merit awards are fairly based and the value of the awards may be insufficient to motivate staff. There is evidence that an increase of at least 10–15 per cent is necessary to stimulate greater effort.7 In the UK such awards have averaged only 7 per cent.8 The ‘pay for performance’ schemes described in Chapter 12 are now making their mark and have replaced many former merit schemes.

11.13 Team working

Team working is now becoming increasingly common among UK manufacturing companies, influenced by the successful example of Japanese companies setting up on greenfield sites in the UK.9 It has subsequently been adopted in some large offices for white-collar workers. The flattening of management structures has widened spans of control, leading to the development of team working as a means of managing in this new environment. However, progress in developing corresponding forms of team-based pay has been rather slower. An Institute of Employment Studies survey found fewer than 10 per cent of organisations with team working had any form of team-based pay.10 A more recent IPD study found nearly a quarter of the organisations in its study had established a formal link between team performance and pay.11 This study found that the most popular approach was the use of team bonuses or incentive pay, but team payments were also used as part of the individual assessment process or within a competency-based pay scheme. The main reason given for developing team rewards was the need to encourage group endeavour rather than individual performance. While over half of the respondents in the IPD survey were confident that it had improved team performance, only 22 per cent could quantify the gain.

The evidence is that team-based pay must be introduced with care, and depends on the existence of well-defined and mature teams. It should not be introduced in isolation, and should be supported with non-financial rewards such as positive feedback, praise and recognition.

11.14 Employee benefits

The management of employee benefits is an important part of pay policy and reward management. The cost of benefits can amount to more than a quarter of direct pay costs, and benefits play an important role in attracting and retaining staff. Many employee benefits which are now part of the employment package started out as welfare services. As well as pensions and holidays, typical large company benefits include company cars, subsidised catering, life assurance, private health insurance, assistance with mortgages, day nurseries and social facilities. To this list some would add forms of deferred pay such as share options and profit sharing.

A philosophy of pay for performance favours ‘clean cash’ in preference to expenditure on benefits so as to reinforce the link between rewards and results. However, benefits are popular with many employers. The company car is now established as an important ‘perk’ in the UK. Some companies favour a ‘cafeteria’ approach (sometimes termed ‘flexible benefits’) for executives, allowing a degree of choice between various benefits and cash, as long as the cost to the firm remains the same.12 This element of choice is held to increase the attractiveness of the rewards. Experience indicates that three factors in particular have to be watched carefully if cafeteria benefits are to succeed — tax law on benefits, control of the costs of administration, and communications.13 Employee benefits should be reviewed on a regular basis to ensure that they are still achieving the desired results and that the organisation is getting good value for its money.

11.15 References

1. Fowler A. How to choose a job evaluation scheme. IPD Personnel Plus 1992; October: 33–34.

2. Spencer S. Devolving job evaluation. Personnel Management 1990; January: 48–50.

3. Wickens P. Job evaluation mitigates against change. Personnel Management 1988; April: 11.

4. Incomes Data Services Ltd. Bonus schemes. Study 547, 1994; February.

5. Kinnie M. Performance related pay on the shop floor. Personnel Management 1990; November: 45–9.

6. Hanck WC, Ross TL. Sweden’s experiments in productivity gainsharing: a second look. Personnel 1987; January: 61–9.

7. Kanter RM et al. From status to contribution: some organisational implications of the changing basis for pay. Personnel 1987; January: 27–33.

8. Murlis H. The myths about performance pay. Personnel Management 1993; August: 18.

9. Incomes Data Services Ltd. Teamworking. IDS Study 516. 1992; October.

10. Thompson M. Team based performance pay. Brighton: Institute of Employment Studies, 1994.

11. Armstrong M. How group efforts can pay dividends. People Management 1996; 25 January: 22–7.

12. Incomes Data Services Ltd. Flexible benefits. IDS Study 481, London: IDS, May.

13. Woodley C. The cafeteria route to compensation. Personnel Management 1990; May: 42–45.