Smoking Gun; by Gueorgui Petzov, Brooks Institute of Photography, CA, student of Joan Pecoraro

8

Measuring Education…Tests, Grades, and Evaluations

“I know that if I'd had to go and take an exam for acting, I wouldn't have got anywhere. You don't take exams for acting, you take your courage.”

Edith Evans

More headaches and heartbreaks are associated with evaluation procedures than with any other aspect of education. This is equally true for learners, teachers, and programs. Before delving into the various types of evaluations used in education we must come to a general understanding of why we need to evaluate at different places in the educational system. Evaluation is a process that allows us to determine how we are doing. The Encarta® World English Dictionary defines evaluation as “the act of considering or examining something in order to judge its value, quality importance, extent, or condition.” It is a process, not a rating.

Evaluations are a conscious act. We may enter easily into evaluating within education: it is a regular portion of the flow of the system. Learning and progress are built on evaluation tools, and the more formal the education, the more structured the evaluation tools.

“Evaluation needs to be done on a regular enough basis so no one is surprised by what is going on. The administration should work with the program to make sure that it stays where it needs to be; the administration should be the catalyst that makes things happen.”

Art Rosser

Clayton State College and University, GA

In education, evaluation is a process of making judgments on human performance. Thus we characterize a learner as a good or bad student or as fit or not to take a specific job or enter a specific program of study. In the end, evaluation is a subjective process. The difficult thing in the process is to move the fulcrum to put as much balance toward the objective side as toward the subjective side.

For the Learner

The importance we attach to evaluation methods, particularly grades, is shown by our using them as a basis to admit learners to programs, to put them on probation or dismiss them, and to award degrees, scholarships, and other honors. Many educational situations are defined by specific grade requirements.

Though many forms of evaluation tools have been created to rate performance, to allow comparison to the course objectives or to other learners, grades are the application of evaluations. It seems like a neutral statement to say that grades are simply markers of progress or completion, but grades are very heavily loaded with many other personal and institutional meanings. Before addressing the applications of grades, let us discuss a major tool for establishing a grade—testing.

The Test

Testing is intended to provide data that can “objectify” evaluation. A common factor in testing is that we wish to gather the data for the evaluation in a standard, consistent, or specified manner. The test has often become a synonym for a grading method, but it far exceeds a simple method for applying a grade to a student's performance. Testing works in many aspects of the overall evaluation of the learning process. It is only one part of the evaluation procedure. When we make a difficult judgment to assign a grade, we must bring to bear on it all information we can acquire. A test will only be part of this process.

Tests can be used to establish abilities within a specific setting of performance for any type of learning. Tests are not just for cognate knowledge but can be constructed to assess learning of any kind.

“If you want to improve something, start measuring it.”

Peter Lewis

Progressive Corporation

Functions of Tests

There are many uses for tests. They function, in one way or another, to evaluate some activity within the learning process. Following are eight different functions for test instruments. They show how testing can be used for evaluation, encouragement, prediction, and/or, most importantly, to promote learning.

First, in its most basic sense the test measures the ability of the students to perform some defined task at some time. We test to see whether or not the student can calculate an equivalent exposure or describe an ambrotype. We use tests to sample the student's knowledge, vocabulary, and procedures or the student's understanding of the part of photography being discussed in the class at hand. This use of the test instrument is most commonly associated with grading.

In this way the test will be a tool that can tell what the student knows or doesn't know. Tests can be constructed to measure either knowledge or lack thereof. We must be careful to realize that the purpose of the test is to advance learning and not to establish that we appear to know more than the students. The test needs to be a vehicle that helps the student understand what learning has been accomplished and not a method to make the students feel poorly about learning photography.

Next, tests are used to classify students. And in many educational institutions students are grouped according to estimated ability. The theory is that teachers can make learning more effective for more students if nearly homogeneous groups can be formed. Particularly in offerings that admit students without regard to previous study, such as vacation workshops, the test can be used to separate cohorts and allow each student to work at his or her own level. Additionally, in programs with prerequisite admission to specific courses, placement tests can be used to allow students to skip areas of study where they can display an appropriate level of knowledge or proficiency.

A third use for tests is to fulfill administrative requirements. Test scores are needed, we are told, to determine when students should be promoted or held back, toward honors, and so on. Further institutional tests are used to give validity to the program. Standardized tests, as well as others, have also been adopted by industrial and other noneducational institutions and are used to decide who will get a job or who will be moved up the ladder.

Fourth, and more bluntly, tests are sometimes thought to measure the effectiveness of the teacher. We must see that tests, both those our students take that measure the learning in the course and those prepared externally to our course structure, can be used to estimate the effectiveness of the learning situation. Quite clearly, it is inappropriate to use test results as pointing directly to the teacher alone, since so many factors affect the quality of learning.

To let the students and the teacher know how the learning process is going is the fifth function of tests. We may believe, or hope, that our students will understand how to carry out a particular procedure. We give the test to confirm or contradict this disbelief. On the basis of the test results we will either decide to continue with new subject matter, or to help the students learn what they have so far failed to learn. This function will not at all be served if we discover a failure of the learning process but then do nothing to correct it.

“Assessment is most effective when it reflects an understanding of learning as multidimensional, integrated, and revealed in performances over time.”

American Association for Higher Education

A parallel construction to this type of test is the pretest given at the beginning of a course; a pretest is built on knowledge or skills that are required to successfully start a class. While not evaluative for the present course, a pretest establishes the starting level of the student cohort. This is exceptionally helpful to avoid advancing beyond the preparation of the learners and then needing to retreat in teaching to address presumed knowledge or skills.

The sixth function of tests is to predict future performance. The function is most often applied as an “aptitude” test that is intended to uncover the talent of students.

The seventh and eighth functions are uses that increase learning through the testing paradigm. The seventh is to motivate students. We may think of tests as devices that force students to study, and many teachers believe that without tests students would not learn. Thus we use test scores as a reward. This understanding in the student cohort can convince many that the effort to learn and understand the materials is worth pursuing. Constructing the test and sharing the test construction rationale can motivate learners to bring their thinking into line with the goals of the learning. When we emphasize answers and minimize the importance of minor blunders, we reward the concentration that is used to arrive at the right answers and correct thinking. If the students are motivated by realizing the test will evaluate these constructs, then the effect will assist in learning.

The eighth function of tests is to assist in the learning process. Tests perform this function by informing students about what they are expected to learn and can further provide a meaningful opportunity to apply and codify the learning process. We construct tests that include a reasonable sample of the activities that we want students to learn to do well. We give them an opportunity to show that they can arrive at the right answer and we may find that the act of testing can be the learning spark. The kinds of questions we use will determine in part the kinds of effort the students will make. Thus, if the questions require recall of memorized items, students will learn to spend their time on memorization. If, on the other hand, the test questions require application of information and principles to solving problems, students will understand that their study must involve practice in problem solving. If the test is constructed to lead the learner through a series of steps and coordinated answers, the test, while being attended to, will also teach the proper thinking and problem solving desired.

The kinds of tests we construct can direct to the students' learning activities more effectively than can our preaching to them. A well-constructed take-home test that allows the students to work with other students can provide them with a study/learning tool, with the emphasis on the solution and learning, not on score.

“Assessment makes a difference when it begins with issues of use and illuminates questions that people really care about.”

American Association for Higher Education

What Tests Can and Cannot Tell Us

Not every test can carry out the eighth function. Different tests will have different purposes, and will be constructed to serve those purposes. To clarify the nature of different tests we present the following six attributes that should be considered when deciding whether and how to use tests.

Test scores are subject to sampling errors and other sources of variability and uncertainty. Once we go beyond testing well-defined skills, we find it difficult to devise and score suitable tests. However, tests can give a snapshot of “facts” or methods that the learner possesses at the moment of testing.

Next, we can test limited education results, but not more complex, and within photography more meaningful, learning objectives. Tests of problem-solving ability are hard to construct, to say nothing of artistic abilities, photographic intelligence, and attitudes. The fundamental difficulty arises from our inability to define what we want to measure. Are we measuring visuality or the ability to perform a prescribed lighting pattern? Does being able to state how lights should be set to produce Rembrandt lighting assure that great portraits will be made? Since factual knowledge is easier to test, and with the image being created not tied totally to the “facts,” tests have a noticeable weakness in evaluating all of the learning and abilities needed to succeed in photography.

The third problem with tests is found in their predictive value. Even the best tests, standardized tests of ability, are not very good in predicting value. The statistical correlation between test scores and success later on shows that the chance of correctly predicting success in a photographic career based only on test scores is small.

In general, we must adopt a frank and healthy skepticism about the entire process of testing. It is not that we discount testing completely but that we recognize that within photography we will need various methods to evaluate learning and progress.

This brings us to the fifth consideration, that a test must be considered as only one of the methods of evaluating learners, and that the other techniques need to be given heavy weight. While tests try to objectify learning, they do so by reducing and defining correctness to measurable and quantifiable answers. This equates correct answers to knowledge and abilities, though correct answers only represent knowledge of the factual bases that are the underpinning of creating images. For this reason, corporate interviewers, in their evaluations of job applicants, consider the past judgments of teachers and others who have had opportunities to observe the applicants' behavior, regardless of the “subjective” and time-consuming nature of such judgments.

“The main part of intellectual education is not the acquisition of facts but learning how to make facts live.”

Oliver Wendell Holmes

Last, most permanent student records contain both too much and too little information. Many times tests have too much bearing on the record. Records may contain too much that is obsolete, and therefore of no value at present and of less for the future. Some method should be adopted to expunge from the record youthful mistakes that may otherwise haunt the student indefinitely. A record, in many cases, also contains too little if it contains only test scores and grades derived from tests, and omits other data that would help to describe the student's abilities. Knowledgeable job interviewers invariably insist on talking with others about the student, because they understand that the written record can be generally inadequate and often misleading.

What to Test

Every question on every test should be related to the objectives of the course in which the test is given. It should be clear to the students, as well as to the teacher, that the questions are fair in the sense that they bear directly on the stated and published objectives.

Well-constructed tests help course objectives become clear to the learners. We can assist this clarification by discussing with students in advance what kind of test will be given and how the questions will amplify the objectives for the course. It is especially important to review tests with the students and to point out how the construction of each question relates to what they are expected to learn.

“You have to go back to your objectives. You created your objectives, you write your tests and then design your instruction to assure that you are testing what you said you were going to test. To make sure that you are teaching what you are testing and testing what you are teaching.”

Ike Lea

Lansing Community College, MI

The concept of a test is a general idea and has several manifestations. Most common of these are the quiz, a short test of low value, and examinations that are more comprehensive and tend to carry a heavier grade weighting. Since these two kinds of tests have different functions, they will necessarily be different in format.

During a course, we may wish to give frequent short tests as motivational devices, and as instruments to discover how well students are learning specific areas of knowledge or attaining skills. Quizzes are used to sample information and relatively fragmentary skills and undertakings. We often make these tests objective, simply because we must grade them quickly and use the results as a basis for review.

At the end of a course, we use tests to assess the status of the students after they have been exposed to a significant amount of information. Final examinations, which must be more comprehensive, tend to be more general and less specifically focused. Therefore, when this is the case, finals will almost necessarily be subjective in character. Particularly when a class is large in scope, such as a survey of photographic history, the subjectivity enters in as the test is constructed and portions are selected in the larger body of knowledge.

Constructing Test Questions

Short-answer tests—multiple choice, true and false, fill in the blank— are more often called objective tests. Probably a better term is “restricted-response” test, implying that the field of answers in which the student can exercise a choice is limited by the form of the question. Written essays or oral examinations, usually called “subjective,” may then be called “extended-response” tests, since the students have considerable freedom to decide how they will answer the question.

It must be understood that the type of response defined by a question not only affects those taking the test but also impacts the constructionof the test and the difficulty in grading the test. Normally, restricted-response tests are more difficult to construct, if they are to determine the students' knowledge, and easier to grade; the correctness of the answers is obvious. On the other hand, extended-response tests tend to be easier to construct and more time-consuming to grade.

The difficulty in constructing restricted-response tests is in developing a questioning strategy that presents the correct answer within the field of available responses, while not directing the learner to any specific response. For a “true and false” question where there are only two available responses, the construction of the statement to be evaluated must present a potential for both the correct and the incorrect response. In this question form, without both potentials, knowledge is not measured.

As an example, the following true and false question shows how the possibility of choosing both a true and false answer depends on the knowledge of the learner. The question—“True or False: Micro-lenses over the gates of a Metallic Oxide Semiconductor (MOS) refocus the light for sharper capture.” For a person unfamiliar with the construction of digital capture devices, the concept of micro-lenses built within the structure of the sensor might be the difficult part to understand. Also, photographers might associate the lens on the camera with the micro-lens described in the question. With either of these lines of thinking being the impetus for answering the question, it will be answered as “true.” With knowledge of the use of the micro-lenses as condensers for the light falling on the sensor, the answer is “false,” which is the correct response. In this construction, knowledge of the learner is the deciding factor in choosing a response.

“Examinations are formidable even to the best prepared, for the greatest fool may ask more than the wisest man can answer.”

Charles Caleb Colton

There are advantages and disadvantages to restricted-response questions. Of the advantages, most notable is the ease in scoring. Multiple-choice and true and false questions can be machine scored. Also, these questions have smaller sampling errors because only specific responses can be used as answers. Further, the student will not be able to attempt to bluff or “snow job” the answer. Next, the test construction can sample the students' ability to apply information to novel situations, as well as recalling information. Last, the teacher can test the ability of the students to make fine distinctions through question construction.

There are also defects in the use of restricted-response questions. While this type of test is often called objective, it is highly subjective in the selection of statements and questions that are constructed for the test. Fill-in-the-blank questions may have very specific answers, such as “The amount of light entering a lens at f2 is______times greater than at f2.8.” Or “______had the greatest effect on artistic photographers of the 1930s.” The exactness of the answer is not found in the questions.

The next problem with restricted-response questions is that they tend to be either trivial or ambiguous. If they are trivial, they can only require recall. If they are ambiguous, they are hardly objective. Further, restricted-response questions, by their very nature, cannot sample the students' ability to generalize, to organize, to synthesize, and to weigh the consequences. It can be argued that the most important educational objectives cannot be reliably measured by such questions.

The two final disadvantages of restricted-response questions both revolve round the concept of guessing the correct answer. First, and primarily, with multiple-choice questions, there may be a penalty for students who think deeply, who can find implications, and who realize that there is more than one potentially significant answer. An example might be “The most light will be absorbed by an object whose color is (black, white, yellow, blue).” A superficial choice is black. More insight involves recognition that the kind of light is not specified and that in some cases a blue object may absorb more red light than does a black object. The guessing factor is often cited as the reason to avoid multiple-choice, true and false, and matching questions. Guessing on these types of questions cannot be distinguished from correctness or errors that indicate knowledge or misinformation.

Similarly, extended-response tests have their advantages and disadvantages. Questions can sample the ability of the students to weigh the consequences, to synthesize information, and to organize data. Extended-response questions also permit the teacher to estimate the students' ability to express ideas in a coherent logical form. The last advantage of extended-response questions is that the student need not make snap decisions. Instead he can consider serious problems thoughtfully. He may exhibit an analytical ability that restricted-response questions can elicit only with great difficulty, if at all.

There are three disadvantages to extended-response tests. Essay questions are time consuming, both for the student in answering them and for the teacher in scoring them. Second, scoring responses is most difficult. Agreement among different scorers is poor. Successive independent estimates of the quality of responses vary remarkably, even for a single scorer. The grades given to a specific response depend upon where the response happens to come in the sequence of responses. Some teachers have a tendency to grade liberally, others to grade harshly. Also, as the grading process extends in time, teachers may grade either in a more liberal way or strictly, depending upon the time involved to that point. Last, a student's inability to write well may conceal genuine understanding. It is most difficult for the teacher to detect the mastery of concept in an answer that is marred by grammatical lapses and misspellings. This is particularly the problem when dealing with students whose primary language is not the one used for instructions and tests.

“How well something is said is important but not as important as what is being said.”

Richard Fahey

Nontraditional Testing

Timed-monitored tests are not the only method that can be used to ask questions to assist evaluating the learning in a photographic program. Of these nontraditional approaches to testing are oral examinations, open resource, and take-home examinations.

Oral examinations provide a one-to-one dialogue between the teacher and the learner. This type of examination is most often used at advanced levels. Such evaluations provide a skilled teacher with a flexible way to interact with the learner and to delve into a list of open questions, to evaluate the larger understanding of the subject, as compared to a small, objectified response set. Oral examinations aid the creation of good rapport, which assists in the overall educational process. While oral exams have these positive attributes, they are very time consuming, have a tendency to produce anxiety for the learner, and tend to be nonuniform from student to student.

Open-resource tests indicate that students will be able to use information in the completion of the test. There are many variations of this type examination. The students may be told that they may use their textbook. While an open-book exam appears to provide access for the students to correct responses for the questions, in many cases this format of exam reduces the students' involvement in correct preparation for the testing. One of the concepts behind using an open-book test is that it can estimate the ability of students to apply, rather than to merely memorize and regurgitate, information. Such a test is a good model of what professionals do in working out problems.

Another open-resource test format is to allow all the students to prepare and bring “crib notes” to the exam. If the learner must prepare their own notes that will be used to assist on the exam, then their learning cycle has been augmented by attending to the information that they have to prepare as part of the crib notes. The learners' efforts in summarizing the information further facilitate learning. A further expansion of this concept is to allow the students to use their own notes taken in the class or from the textbook, as a resource for the test. This method has three effects on the learning process. First, if the students realize from the beginning of the course that the notes will be usable on the exam, they will likely take better notes in class and thus pay better attention to the course material. Next, the fact that they write down information either from the class meeting or from the text creates an opportunity for the information to be more permanently learned. Last, as the students organize their notes into a usable resource for the exam, they will see “holes” that may need to be filled for the exam. This will encourage them to find resources that they can include in their notes.

“Assessment…is only as good as its instruments, and is defensible only to the extent that it actively forwards and enhances…learning.”

Theodore Sizer

Coalition of Essential Schools

Exams may also be taken outside the monitored environment. Often called a take-home exam, this testing paradigm provides a more relaxed impression of the testing situation. Many teachers are concerned that cheating will happen when the exam is not monitored, and while there is a potential for cheating, the take-home concept provides a better opportunity for the tests to become a learning tool. At advanced levels, it is quite common to assign term papers or student-selected questions, to be answered in essay form using a series of questions. This provides an opportunity for the student to utilize information and data, to allow synthesis of ideas that demonstrate their understanding of the test/term paper questions.

When the exam may be taken home, and the teaching assumption is that help will be garnered for test completion, tests can be constructed that assist the students in learning. While this is not particularly helpful for restricted-response tests, where complicated processes are involved, the aspect of peer interaction to assist the learner is highly beneficial. Because the learner is highly invested in the outcome of the test, finding constructions for the test that utilize peer interaction can create an opportunity for learning.

Grading

In education today, grades have become a necessary part of the evaluation process. While grades are important for many aspects in education, their usefulness as predictors of later accomplishments is suspect. Grades often put undue pressure on learners and can change the way learning happens. The process of giving grades is a two-edged sword. Grades can become divisive ego-driven elements in education or they may also become a tool to encourage learning.

“If I were asked to enumerate ten educational stupidities, the giving of grades would head the list.…If I can't give a child a better reason for studying than a grade on a report card, I ought to lock my desk and go home and stay there.”

Dorothy De Zouche

Grading happens first on testing and assignments and then on the course. Grading assumes a measurement of learning. While grades do not accurately show learning, they are ratings of progress in learning. The rating scale, which is prescribed for any grading system, has elements of arbitrariness built into it. As soon as a grading paradigm is projected to rate learning, a somewhat arbitrary or subjective scale has been applied.

We can think of grading as a relative or absolute process. But an absolute scale of grades can be attempted, where 70% indicates that the learner has mastered the learning needed to function in photography. However, why should the absolute be at 70%? Perhaps it should be at 60%, 80%, or 90%. It can be argued that unless a 100% grade is attained, mastery has not been proved. Choosing the absolute nature to be applied to learning photography inserts arbitrariness into the process. If there is an advantage to attempting an absolute grading scale it is that it can become a mathematical rating scale.

To further the argument about the arbitrariness of grading, let us assume that there is a potential for using a “curve” to establish a rating scale of performance. Students often ask teachers, “Do you curve your grades?” By this question they mean, “Do you restrict the number of A grades, etc., to some fraction of the class?” or “Can I earn a good grade regardless of the performance of the rest of the class?“

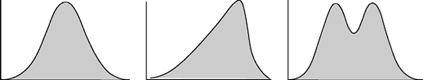

A curve grade is derived from the use of plotting of all grades in units and then using a statistics measurement to segregate the pool of grades into ranking units (As, Bs, Cs, etc.). The “curved grade” is based on a distribution curve. A normal distribution curve shows the vast majority of grades in the middle of the grade range, with decreasing distribution of grades as the scores move in both directions from the middle of the grade range. Without going into a long discussion of statistics, commonly the mean and standard deviation are used to segment the grade range as seen in the curve. The mean is the center point of the distribution and the standard deviation is a statistical measure of a specific difference of values from the mean. Two other terms worth mentioning are “skewed,” which means that the curve has more of the distribution toward one end or the other, and “bimodal or multimodal,” meaning that there are two or more concentrations or groupings within the distribution curve.

“I have learned that success is to be measured not so much by the position one has reached in life as by the obstacles which he has had to overcome while trying to succeed.”

Booker T. Washington

Normal, skewed, and bimodal distributions

If a teacher, or an administrator, decides that A grades will be given to the uppermost 10% of the class, this decision is in no way related to, or dependent upon, the shape of the curve describing the grade distribution. Out of the class of 50 students, five will receive an A no matter whether the distribution is strongly skewed or bimodal or any other shape. Thus if this is the decision that is made, the question about “curving” grades is irrelevant because an arbitrary number of A grades have been selected, regardless of the outcome of the evaluation tool.

If the decision, on the other hand, is based on cutoff points defined in terms of some number of standard deviations from the same mean of the class distribution, the percentage receiving A grades will depend greatly on the form of the distribution. We may say, for example, that all students receiving scores above two standard deviations from the mean will be scored A. Now the percentage of students receiving A grades will be greater for a distribution skewed to the low side, and fewer for a distribution skewed to the other direction. This is because, as the mean rises toward the highest grade possible, the scalar amount of scale above the “arbitrary” two standard deviations may not be available.

The two preceding methods of curving are relative, in the sense that they grade depending on the performance of other students, and thus are not constructed with this single scale of merit. To the extent that successive classes are similar in ability, as estimated by the examination, we can suppose that a grade of A in one class is equivalent to a grade of A in the following class. But it is, on the contrary, more reasonable to suppose that a time trend exists. No doubt successive classes improve in ability and grade performance. Thus we should expect the proportion of good grades to increase if the test maintains the same level of difficulty. Also, a teacher gets better from year to year, or ought to.

Alternatively, like an accelerating treadmill, we may make the required level of performance rise as the students attain higher levels of learning, and make the test harder as the students become better. In this case the proportion of grades in a given category will remain essentially constant, on the assumption that the teacher is skillful in adjusting the required performance level to relate to the increasing abilities. Such must be this situation, for example, in the New York State Regents examinations, for which the passing grade has remained constant from time immemorial. Note, however, the frequent practice of the examiners in lowering thepassing grade when this test fails an abnormally large amount of students. The passing grade has never, to our knowledge, been raised.

For testing we recommend several points for consideration. First, when assigning percentages to different grade categories (A, B, C, etc.), do not assume a normal or even symmetrical grade distribution. Most classes represent too small a sample for normality or symmetry to appear. While multiple classes taking the same test may provide a statistically valid number of scores to create a useable distribution curve for an exam, a correlation will only have validity if the test is consistent in content, environment, and timing over all tests.

One of the difficult components in effective teaching is preparing fair and valid test questions; questions are “valid” in the sense that they relate to the stated objectives of the course; they are “fair” in that they are not tricky or ambiguous. Testing and grading are an integral part of every educational program and should be viewed as such by both students and teachers. One can think of testing as a “feedback” component in which a student acquires some measure of his learning and the teacher acquires a measure of how affective he or she was in facilitating that learning.

“Like so many teachers, I failed to understand that testing and grading are not incidental acts that come at the end of teaching but powerful aspects of education that have an enormous influence on the entire enterprise of helping and encouraging students to learn.”

Ken Bain

Center for Teaching Excellence

New York University

By Elizabeth Moreno, Colorado Mountain College, CO, student of Buck Mills

In institutions of higher learning, a higher proportion of good grades, rather than poor ones, are assigned, because the number of poorly performing students usually progressively decreases through admission policy, discouragement, or attrition. The proportion of students earning high grades should increase as the students' educational process progresses. This should not be taken as a suggestion of grade inflation; higher grades should be expected as the level of education increases.

Utilize the total grade scale. Using only the high end of the grade scale (only A, B, and C), and considering a grade of C as essentially failing, must be discouraged. The weeding-out process, normally a part of increasing educational levels, plus reasonable admissions procedures to higher education programs, should ensure that only competent students are admitted. To the extent that the admissions process is successful, advancing students should earn excellent grades or at least grades that are superior to those earned in previous education.

It must be clear that the educational process is one of the places in life where failure has the best potential of being positive. Particularly in the creative parts of photographic education, failure must be seen as part of the path to success. A failing grade can have a variety of effects, not all negative. Thus using the full scale of grades, including failure, is using one of the tools of education. However, because of the human dimension, the use of failing grades and the method of demonstrating failure in assisting learning are very important.

Success and Failure

Every student wants to succeed, even if it seems to the teacher that the student “is trying to fail.” All students want to be “accepted” by their peers, teachers, and parents. Success is perhaps the most powerful stimulus for the student to continue their learning.

Every teacher wants students to succeed. Having our students do well strengthens our belief that we are good teachers. All parents want their children to succeed. The success of the child is a sign that parental responsibility has been properly discharged.

Why, then, do so many students fail? The reasons are many. First, standards of success or failure are externally set, imposed on the students by the curriculum, by the course, by the teacher, or by the parents. Does a 50-year-old college professor fail if he cannot run a four-minute mile? Is it failure if a two-year-old child cannot walk? Why, then, is the passing grade on a photo examination 70%?

Next, many students have rarely encountered a learning situation where success is ordinary. Thus they have fallen into a routine of failure. They have been continually told, in effect, that they are no good. It is not at all astonishing that these students turn to noninstitutional (school) situations for learning satisfaction. Many delinquent children are capable learners, as shown by the skills they acquire on the streets.

Also, many well-established educational procedures foster the feeling of failure. When we mark tests we are emphasizing failure. We check errors rather than right responses; we point out mistakes rather than give credit to almost-right solutions; we demand perfection although we are rarely perfect. (A “Family Circus” cartoon shows a disappointed father looking at his child's report card. The child, in an explanatory posture, tells his dad, “But I knew the answers to lots of questions that weren't even asked on the test.”)

Finally, students set their own standards of success and failure. They give up if the learning process is too difficult for them, without having a genuine feeling of failure. Similarly, if the work is too easy, students accomplish it with no feeling of success. Thus one of the arts of the eacher is to see that the students engage in activities of the right level of difficulty at the right time.

In real life situations, the ratio of success to failure is small. A writer reworks a sentence perhaps a half dozen times before it is right; the poet often does twice that. The engineer may tackle a problem in scores of different ways, and fail many times before success. The photographer destroys many unsatisfactory prints before he or she is satisfied.

“The pathway leads through failure. That is what makes images work. How do you differentiate a strong image from a weak image? You do it by creating lots of images and your eyes and your heart will choose the same images over and over again. The idea of failure is the essential. In baseball, if you hit .333, you can be in the Baseball Hall of Fame but you failed two-thirds of the time. If you can get one-third of your art to be strong that is a remarkable thing. Failure has rescued the process and given it uncertainty and that is the heart of being creative. If you risk something you risk failure.”

Kim Krause

Art Academy of Cincinnati, OH

The students should be specifically prepared for such situations. They should learn that failure is a normal part of the attempt to solve difficult problems, and not a consequence of a deficiency in their character. They should learn that real problems ordinarily require many attempts at solution. They should learn that some questions are probably not soluble at all, and that others have a variety of answers of different validity.

In a healthful environment even repeated failure is not distressing. A child is learning to walk; he topples over repeatedly but this can be a source of pleasure rather than pain. The weekend golfer many never break 100, but he eventually enjoys the game. Amateur musicians can take great pleasure even when they play badly, and even when they recognize their incompetence by professional standards. In each of these and similar situations, the process itself is enjoyable. Eventually the exercise of even a minimal talent provides pleasure without regard to goals. The essential characteristic of the situation is the absence of an external criticism or consideration. Failure is not seen in the situations, only personal successes.

Assign arbitrary cutoff points on a scale with a full understanding that they indeed are arbitrary. If we give a 50-item multiple-choice test and assign A to scores 42–50 and B scores 38–41, we make a raw score differential of 1, from 41–42, worth a whole letter grade. To do this we must believe that such a small difference in raw score is real, not merely testing error, and also meaningful—actually indicative of a genuine difference between students. This belief is not usually possible to support. Do not assign different meanings to scores that are only trivial differences.

Adopt, at least in principle and as an ideal, the concept that a completely successful educational environment will generate only excellent grades. If the admission and counseling procedures, the teaching and learning methods, and the testing techniques all operate at their appropriate effectiveness, every student will do well. At least, this ideal is our intent if not our expectation.

“If you have low expectations, students will meet them. In my experience, expecting a lot from students frequently leads to getting a lot from them. And more important, it teaches them to expect a lot from themselves.”

Jef Richards

University of Texas at Austin, TX

Conversely, if a student fails consistently or if a class earns a large percentage of bad grades, something is wrong. We should try to diagnose the element, uncover the cause, and try to correct it. We may need to revise the objectives for the students or for the class, to clarify these objectives, or to provide opportunities for more effective practices. Often the problem is with the tests; they may not be consistent with the objectives or methods.

Assigning Final Grades

At the end of a unit or course, we usually have the responsibility for classifying students into categories, usually designated by letter grades. Some institutions use pass/fail, satisfactory/unsatisfactory or credit/no redit grading. Regardless of grading method, no teacher takes this responsibility lightly. Every teacher finds it distressing to sit in judgment and especially to put into pigeonholes human beings who are of infinite complexity and variability.

Some teachers attempt to relieve themselves of the task of making such difficult decisions by resorting to mathematical procedures. We may compute assignment averages, test averages, and laboratory averages by averaging these with the final examination, most often with an arbitrary weighting system. Such a process is time consuming, and we usually find that the hard decisions remain for us to make. We are still left with the question, “Is this student worth B or C?” Often the more distressing question is, “Should I fail this student or assign the minimum passing grade?” The search for an “objective” method of assigning final grades is sure to fail, except in the situation in which the students' performance is so unusual as to be obvious, and in this situation no complex formula is needed.

“Using one test as a high-stakes hurdle is unfair and often inaccurate, violates the standards of measurement professionals, and damages educational quality.”

Monty Neill

The National Center for Fair and Open Testing,

Cambridge, MA

Averaging a set of numbers is statistically sound only when the members (the numbers) of the set are estimates of the same stable process, and when the differences among the numbers are attributable to measurement errors. Thus, we correctly average a set of measurements of the length of sticks with the expectations that the average is a better estimate of the dimension than is any single measurement. But students are not sticks. Testing indeed involves large measurement errors, but what we are trying to measure, the students' ability within contexts, is not at all stable. In fact, we intend that students will change. To the extent that a student does change, a series of tests never estimates the same performance, but, on the contrary, samples different levels of performance. What a student could do in September may have little relationship to what he can do in June, and therefore measures of ability at different times ought not to be combined.

Some students are severely penalized when we average grades. Such students are those who will do well day-by-day but are panic stricken by final examinations and who collapse under unusual stresses; those who start a course badly but finish well; and those who are all thumbs in the laboratory but excellent in theory. Especially when different aspects of the course involve different objectives, averaging grades may produce a set of numbers in terms of which students seem to be mediocre. Other students are over-graded by averaging within-course grades. Such students are those who reach the limit of their ability during the course, but may earn a respectable average despite their having little comprehension of the course as a whole.

When we average sets of estimates that have different means and variables, even a weighted average may be inappropriate. If a group of students earn nearly the same grades on a final examination, for example, but have quite different scores on assignments, hardly any weighting method will make the averages of scores reflect other than the assignment grades.

If it is often invalid to average within-course grades, it is more obviously wrong to average grades earned in different courses to arrive at an average grade for the year, or for a four-year program. Averaging averages from different courses is statistically improper. The principle is merely that it is incorrect to average grades for courses with objectives as different as those for photo history, photo science, and image production. This being said, it must be realized that the GPA (grade point average) used by most institutions is exactly that…an average of averages. Using this institutional standard, we must realize that this can give a trend assumption for each student but not a real rating of true learning.

You Gotta Give Grades

Because the administration of institutions requires our rating of student learning at the end of courses, we are required to assign final grades. Let us suggest six ideas to assist in this task.

“I hate grading…it is the worst part of teaching. Particularly our young students today identify so heavily with the grade as equivalent to the value of themselves. They work toward the grade rather than work toward the passion they have about making pictures. Grades just get in the way of students learning—they get caught up with that number score rather than the significance of their images.”

Roxanne Frith

Lansing Community College, MI

First, realize that in evaluating student test scores we use only one kind of data, and not always the most reliable and valid kind. Accumulate, and use in the evaluation, information about student activities in classrooms, libraries, and laboratories. A balance between different learning styles, when appropriate, provides a better understanding, and therefore a better approximation of learning.

Next, do not try to substitute a statistical averaging process for your considered judgments. Frankly admit the subjectivity of evaluating human beings.

Third, give heavier weight to recent grade information as compared with older grade information. If, in a Photo II course, the student's assignment grades chronologically were D, D, C, D, C, C, B, B, A, B, the student clearly acquired above-average skills, and his final grade should be B, not the numerical average of C. Even in the extreme cases where the student does poorly all term, but shows on a final examination that he has by that time mastered the material, he deserves a course grade better than the average of all his grades, which reflects heavily on the grades in the early and middle part of the term.

Fourth, the most troublesome set of grades is one that isolates between good and bad performance. If this sequence is A, D, F, B, A, C, A, and average would be C, but this set of grades indicates that the student is by no means mediocre; on the contrary, he has indeed demonstrated that he can do good work, and also that he often does not have the incentive to do good work. The teacher has a hard decision, which must be based on what he wants the final grade to show: if the mark is to indicate the student's capacity, it must be at least a B; if the mark is indicate the least level at which the student functions, it should be D. In the latter case, the student's desire to do the work is being evaluated; in the former, his ability is evaluated. A C grade does not indicate accurately either ability.

“What students learn depends as much on your tests as your teaching.”

Wilbert McKeachie

University of Michigan, MI

Next, some of the hard decisions would be eliminated if a “pass/fail” grading system were adopted. Such a two-point method has been used and has recently been adopted by prestigious educational institutions. However, a strict understanding of what is expected and what must be accomplished to receive a passing mark needs to be presented at the beginning of the course, to create a defining point of acceptable learning level. The pass/fail grading often is difficult within certain institutional situations, since the GPA will not be affected by the pass grade, but will be detrimentally affected with the failing grade. This may put undue pressure on the teacher to lessen the number of failing marks given in the course. One method to address this potential problem is to use “credit/no credit” as a grading system. It must be mentioned that if a specific GPA will be needed by the students for further education, scholarship, or employment, the number of courses allowing either pass/fail or credit/no credit grades should be limited within a program or curriculum.

Sixth, for classes small enough for all students to be well known by the evaluator, a statement about a student's characteristics is better than a letter grade or numerical grade. The process of writing a paragraph about each student is exceptionally difficult for the teacher, but it has a virtue of compelling the teacher to think seriously about the performance of each student.

“The roots of education are bitter, but the fruit is sweet.”

Aristotle