8

Planning the Implementation

When you are planning the implementation of a productivity improvement, you must perform the same tasks as you would if you were planning for the development of a system. You must have a strategic plan and a tactical plan, as well as a detailed set of plans for the actual implementation. The reason that you must keep the long-range perspective in mind is directly related to both the potential future ramifications of effecting change and the time that will be required to complete the change process.

The Strategic Plan

There is no doubt about it: If you are successful (and you will be), not only will you irrevocably change your present environment, but you will also have tremendous impact on the future. Thus, you must consider what the future scenario would be without any planned productivity improvement, as well as what it will be with the changes you have envisioned. The first thing you must do is take stock of where your organization (and indeed your entire company) is headed. To achieve this objective, you might consider utilizing your informal network, which may well already extend into the corporate planning groups. (If you do not have connections with these centralized groups, establishing them should become a priority, because it will be very important later on in the change process.) You do not need an exhaustive study of the strategic direction of your company, but rather high-level information so that you will have some general sense of the future for positioning purposes. It will also facilitate your ability to position the implementation plans for the future if you are aware of any near-term and long-range major organizational changes that are being considered. This task is quite vague, and really all you can do is keep yourself linked into the rumor mill and remain as politically attuned as possible. We do not recommend wasting time or energy on this, however; we are suggesting that if you do come across this type of information, factor it into your planning equation.

The final and most important area that you must take into account for strategic planning is the direction in which technology is headed. We understand that this is about as easy as building a crystal ball and then trying to become psychic. However, there are some methods that are readily available to all of us. The most straightforward and obvious option is to keep yourself informed of the current technological situation. Of course, that can become a full-time job. Let me share one way I deal with the dilemma. I do make an effort to read one article a day from a trade journal, and I try to avoid always referring to the same one. More important, I rely heavily on friends and associates for information.

All of us know people who spend hours each day gathering information about the current state of technology and where it is headed. These are almost always the same individuals who spend considerable energy analyzing and predicting future technological directions. By all means utilize this excellent resource; there is no need to perform tasks personally that are already being performed by others. Moreover, this technique is merely an extension of skills that you employ every day as a competent supervisor; you delegate a task to an employee and then have that person brief you on the results. The difference here lies in the fact that there is no need to delegate or request a briefing, because your “techy” friends are already performing the task. Moreover, they actively seek opportunities to and thoroughly enjoy doing the briefing.

Let’s pause and summarize areas to consider for strategic positioning of the change process during the planning phase:

• Attempt to assess reasonably accurately the strategic direction of your organization and company.

• Be as aware as possible of any major organizational changes that might affect the productivity improvement you are implementing.

• Keep informed of technological directions that might affect your efforts.

The Tactical Plan

Now let us examine the length of the change process and its relationship to tactical planning. Do not delude yourself about the amount of time that will be needed to complete the change process. The effort required to bring about the cultural adjustment that results from the successful erosion of resistance will take years. On the other hand, do not view this fact with discouragement, because you will realize substantial benefits within a matter of months. Moreover, many methods for achieving these multiple intermediate results will be outlined in several chapters (including this one). The fact is that although you must give some thought to developing detailed implementation plans for the next 6 months, you must also give some thought to where you want to be in a year or two. Then you can formulate some high-level but specific items that comprise your objectives from a tactical perspective.

All this strategic and tactical planning should be done solely by you and your group; there is absolutely nothing to be gained by involving the interproject team in this effort. Indeed, you do not want to spend a great deal of time and energy on these steps. They are important as points of reference to be used during the detailed planning activities. Some items to bear in mind about tactical planning are these:

• Since the entire change process takes years to complete, you need to consider where you want to be in one to two years.

• You do not need to develop a detailed tactical plan; a simple list of your objectives will suffice.

• Do not involve the interproject team, because you do not want to spend substantial resources on this.

• Even though the time and effort to prepare the tactical plan should be minimal, it is important and should not be omitted.

Strategic and Tactical Planning—An Example

To provide some concrete examples of what all this means in practice, let’s look at some of the strategic and tactical planning we used during our implementation of data management. Initially we were given the charter to provide data management tools and techniques for only one-third of our organization; however, we perceived from the very beginning that the function we would be performing would naturally extend to a part of the department that was outside our scope. Therefore, we included on our interproject team representatives from these other groups. We utilized information provided by these people as well as our own understandin of their part of the organization to ensure that everything we planned would also accommodate their needs. We were correct in our assessment, and after the initial implementation we did become responsible for the whole department. Moreover, we were able to incorporate these areas without massive disruption to previously developed methods, procedures, standards, etc.

We also sought and maintained close contact with the group that was setting corporate data policy and standards. We obtained information about their activities and shared our plans to safeguard against major and unpleasant surprises in the future. During our implementation, we heard a rumor that there was going to be a major corporate restructure that would result in our organization’s merging into another line of business. We were well aware that the data management groups in that line of business used totally different tools and techniques. Utilizing our informal network, we established an information exchange day. By the end of the day, all sides were able to conclude that although different tools were being employed, all techniques were fundamentally consistent.

Figure 8–1 contains a graphic summary of the process of involving many people for strategic and tactical purposes. It is worth noting that all the activities described here required very little time and people resources, yet the return from the minimal effort was substantial. We did not spend hours or days poring through documents or chasing vague rumors, but we did pay attention to peripheral activities and prudently utilized information to avoid considerable restructuring of the implementation further on in the process.

Figure 8–1 Strategic and Tactical Involvement of Other Groups and Organizations in Team Interactions.

Detailed Plans—How to Develop Them

Having addressed the strategic and tactical planning process, we can now turn our attention to the main work of the planning phase. The major activities of this phase involve the development of the detailed implementation plan, which will be performed within the arena of the newly formed interproject team. Moreover, although this is a pre-implementation phase, there are concrete deliverables. But before we describe these deliverables in detail, we need to address the manner in which they will be developed.

In the gathering information phase, we stated that you needed to “set your course of direction” prior to beginning the planning phase. This basis for the planning phase is a prerequisite because of team leadership issues. You can not expect to lead the project team effectively or have the team members view you as having the personal power unless you begin with a clear idea of where you are headed, and have a basic route to get there already mapped out. Furthermore, it is imperative that you and your group prepare a draft version of each deliverable prior to the project team meeting that will address that particular deliverable. The draft does not have to be elaborate or even complete, because it is intended as a basis for discussion only. However, it is truly essential to have something concrete to begin each meeting with, or you run the risk of the meeting becoming a group grope. You can begin with your group’s proposal, and then you will need to draw from the collective expertise of the team. The result may be a deliverable that does not even remotely resemble the draft, and that is perfectly acceptable.

Do not worry about having a polished and finished document to present; a rough draft is quite appropriate. Actually, you should concern yourself more with the possibility that the proposal will be too polished and will inhibit the other team members from freely contributing to the final product. You must also guard against the possibility that your group will have extended their efforts so far that they will not be open to team suggestions. However, you are the team leader, and you will ensure that your group is prepared with a draft and that the team truly develops it into a final product.

The manner in which the planning will be performed can be summarized as follows:

• The basic game plan was established in the gathering information phase to enable you to begin your team leader role effectively.

• To avoid group gropes you must begin the preparation of every deliverable with a draft document.

• Unless emphasis is put on the draft aspects of the document, the team may not freely contribute and thus produce a quality final product.

Political Hazards

Before we proceed to the deliverables themselves, we must make you aware of some political hazards that have a high probability of surfacing at this particular juncture. Up to this point, no one would have conceived of trying to gain control of the change process. Prior to this phase, all your efforts were directed toward educating people at all levels as to the importance of your activities. Now, however, you have successfully convinced many people that the change is critical in a very real sense for the future well-being of your organization. The natural result of such awareness is not only that people will view it as politically expedient to follow the leadership you are offering, but also that some individuals will perceive that it would be even more expedient to lead the effort themselves.

This type of power politics may emerge any time in the change process, but often the first arena is the interproject team and the first battle is during the planning phase. There are also many ways that people will make an effort to usurp your power; the most direct one is attempting to gain enough personal power to seize control of the project team. Actually this is not a situation that you need to fear because you have the position power granted to you by upper management, and that is sacrosanct no matter how much personal power another individual gains. On the other hand, you do want to retain as much of the personal power as you can, because it will not benefit the team bond if meetings consist of a series of power plays.

There are some coping mechanisms that frequently alleviate this type of situation. For instance, sometimes it helps if you can concede a few minor points. This deferring to the other person may reduce their perception that it is a “win lose” situation. If their ideas (or any team member’s ideas) can be utilized, by all means cooperate. Avoid unnecessary confrontations; there will be enough issues over which you will have to do battle. Remember that your objective is to produce the deliverables and plan the implementation, not impose every one of your own ideas on the change process. We will provide some very specific examples of when to cooperate and when to confront when we describe the establishment of standards in the next chapter.

Another type of power struggle you will sometimes encounter is of a more passive nature. Some individuals will not confront or even argue with you or any other team member, but will instead persist in following their own direction even though it is in direct opposition to everything the team is developing. This kind of behavior is wasteful and counterproductive; and when the team becomes aware of it, quite demoralizing. In general, the techniques described above will not improve this situation, and our recommended course of action is to remove the person from the team. If removal is not an option, then you must just outlast the problem. Remember the change effort will move forward, and eventually you will have more ability to enforce the standards, procedures, or whatever it is that is not being followed. We will refer again to this specific situation in Chapter 12, when you will be in a position to resolve this conflict.

In every one of these political struggles, what you must really remember is that you do have the authority to proceed with your mission, and you are the team leader. But, as the change process proceeds, you will face problems that you will not be able to readily solve. You and your group will have to accept and live with some frustration and ongoing concerns. All that is really possible in unresolved situations is to exercise authority and leadership wisely. Keep trying to reach the difficult team members, persist gently in including them, solicit their suggestions, and accede to their best recommendations. At the same time, you must protect the rest of the team from rugged individualism for its own sake or the political maneuvers of attempted takeovers. If you do not maintain control of the situation, you will find yourself and the team on the road to anarchy.

Be patient, kind and firm, and you may find that eventually your good intentions will become apparent and the difficult person will be converted. If not, at least you will have diffused the situation as much as possible and spared the team anxiety. You must constantly endeavor to maximize the progress and quality of the change process. But you must also strive to minimize friction and disruption for the sake of all the people who will be heavily involved or even touched by the process.

The final political battlefield of which you should be aware is that with the increased popularity of your effort, your management at any level may also be struggling to retain control. The only participation that you can have in that political arena is to keep your management chain well informed so that they will have the ammunition to fight their battles. If they lose their war, you may be reporting to another boss, but chances are excellent that your group will be moved as a unit and the change process will continue.

Reorganizations can indeed jeopardize many aspects of your implementation, as we will describe in Chapter 12. At the very least they will slow down the change process. Therefore, anything you can contribute to help avert them will be beneficial to everyone concerned. It is important to note, however, that in a certain sense you cannot really personally lose any of these political battles. It was your conviction that began the implementation, enabled a successful sale of the product, and brought the productivity improvement to this stage. Your enthusiasm is undoubtedly a critical success factor; you are firmly entrenched in the change process; and it would not be easy for you to be replaced. However, you still must maintain as an objective avoiding conflict and neutralizing the political overtones, because they can seriously drain the efforts and progress of your group, your team, and yourself.

Let’s pause a minute and summarize the political battles you might anticipate during this phase:

• Due to the increased popularity of the productivity improvement, team members may try to take over your role as team leader.

• The takeover effort may be in the form of an individual using personal power to usurp your position.

• You may also encounter passive resistance in the form of extreme nonconformity.

• You have position power (due to management sanction) and personal power (steadily increasing), which secures your authority.

• You want to assist your management, if they are facing similar battles, because reorganizations will slow down the change process.

• In general, you need to minimize all disruptions, or the change process will be seriously impeded.

Deliverables

Having spent considerable time on the mode of producing deliverables and the politics involved, we will focus our attention on the deliverables themselves. Here is a list of the most common outputs of the planning phase:

1. Gantt charts that reflect work breakdown structures (phase, activity, and task) to allow for time and resource scheduling, availability, and work status reports

2. Dependency diagrams to highlight the critical paths

3. Standards, naming conventions, and methodologies to be followed by users

4. Documented draft description for roles and responsibilities of both users and change agents

5. Documented draft procedures for managing the emerging environment, e.g. change control and version control

The first item, the Gantt chart, is the facility that allows you to accomplish the following:

• Division of the effort into its phases

• Specification of activities within phases that must be performed

• Subdivision of these activities into tasks

• Identification of who is assigned to each task

• Identification of time (number of days as well as elapsed calendar time)

• Tracking the status of each phase, activity, and task

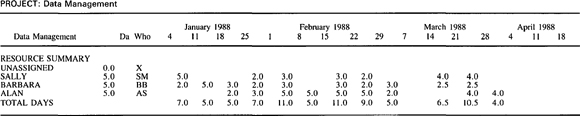

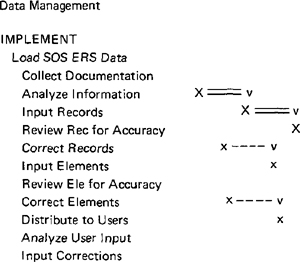

Several PC-based tools are available to automate these planning activities. The report from our data management experience that is provided as an example (see Figures 8–2a and 8–2b) was prepared by PW (Project Workbench), a tool we often use for planning. Figure 8–2a illustrates an activity (Load SOS ERS data) and its associated tasks (e.g., Collect Documentation, Analyze Information, and Input Records) for the implementation phase (IMPLEMENT) of our data management effort. The advantage of utilizing a tool is that you can easily change the inputs, and then the resource scheduling (Figure 8–2b) is dynamically performed. In addition, the numbers associated with the Gantt chart are calculated for you, stored, and are available for reporting at various levels of detail. All this information will be very important during the entire implementation for determining exactly what is on or behind schedule. Figure 8–2a also provides an example of status information; notice that some tasks are depicted on the timeline with double lines (denoting a completed status), while uncompleted tasks are depicted with a single line.

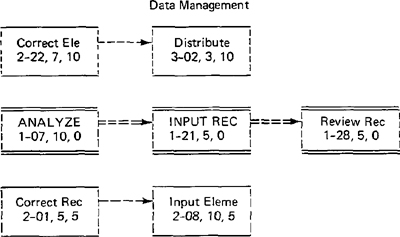

Lines that begin with a C indicate that the task is part of the critical path. This capability of PW is valuable because you can visually depict the minimum amount of time required to complete the project, no matter how many additional resources upper management tries to force on you. Figure 8–3a is a dependency diagram and Figure 8–3b is a CPM network.

Figure 8–2A This Diagram is a Sample Gantt Chart From Our data Management Effort.

Figure 8–2B This Resource Summary, Companion to the Gantt Chart, Indicates Availability (5.0 days per week) and days Already Allocated for Specific Weeks.

In the data management case, it is clear that you cannot begin to Input Elements until you have completed Correct Records. These diagrams also indicate the number of days past the due date that can be tolerated for a particular task without affecting the end date. Thus it is apparent that there is a built-in slippage period of five days for each task. See the last number in the boxes representing these tasks on the CPM network (Figure 8–3b).

It is worthwhile to employ productivity tools and techniques wherever possible throughout the change process. Of course, the primary reason is because it will improve implementation in terms of both speed and quality. In addition, it does add substantial credibility from your users’ perspective that you are sincere in your efforts to improve the data processing mode of operation. The most noticeable and beneficial employment of productivity tools and techniques is when you are able to use the product itself during the implementation. For example, you might use PW to plan its own implementation in your organization.

Figure 8–3a Note that on this Dependency Diagram (companion to the Gantt chart), the critical path is highlighted by double lines.

Figure 8–3b The CPM Network indicates critical path (middle set of boxes), Start Dates, Duration, and Slippage.

Discussion of the third item, standards, naming conventions, and methodologies, will be bypassed for the time being. We believe their judicious use is a critical success factor for the implementation of any productivity improvement, and thus we devote an entire chapter to the subject.

The next item on the list, roles and responsibilities, is a significant product, because as people’s everyday work lives (responsibilities) are modified, there will be as a natural corollary modifications in their professional relationships (roles). Furthermore, although the roles and responsibilities must be addressed in the planning phase because they will both direct and be affected by the actual implementation, this is a product that is in transition—an ever-evolving deliverable.

As the implementation moves forward and the productivity improvement begins to realize some tangible benefits, the relationship between the users, the change agents, and their emerging environment will also change. The goal at this stage of the process is to lay a foundation and establish some basic ground rules. You would realize no benefit from a comprehensive document, such as a charter or service agreement. You just need to supply a deliverable with some substance that will be flexible enough to accommodate the new environment.

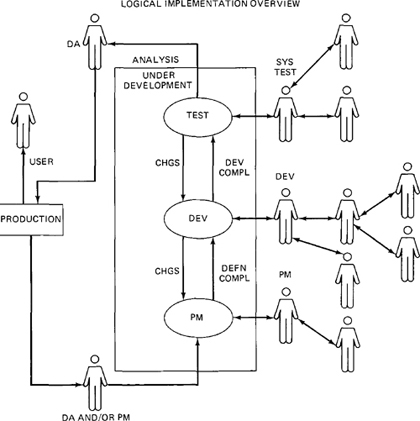

Figure 8–4 contains the logical implementation plan that we developed during the planning phase when we were implementing Excelerator in our organization. This diagram depicted the relationship between my group and the other groups, which were organized according to functional responsibility (system test, designers, etc). The project team developed a proposal that identified who would be responsible for individual versions of each system as they progressed through the development life cycle. As this particular productivity improvement flourished, the roles and responsibilities altered somewhat and became defined in greater detail; however, the fundamental tenets set forth and illustrated in Figure 8–4 held true for years.

The final item on our list may be of minor significance for some implementations or may not even be appropriate for others. For example, if you are incorporating a new word processor into your department, it is doubtful that you would need to invest a lot of time and energy into developing and documenting change control and version control. On the other hand, in the Excelerator example described above, we did indeed establish version control and change control.

In fact, the change control was initiated by a member of the project team. I and the rest of my group were so involved with producing the detailed plans and gearing up for the actual implementation that although we had considered version control, we had never given a single thought to change control. One day a project team member, who happened to be a peer and friend, stopped by my office and announced the need for change control. I immediately agreed. We drafted a proposal, presented it to the team, and after minor modification documented a procedure that basically was never altered. Some things worth noting about this story are as follows:

• The presence and benefit of the informal network in action

• Receptivity of the main missionary to the innovations of disciples

Figure 8–4 Roles and Responsibilities of Each Group in the Organization Indicates which Group will Incorporate Changes at any Phase of the software Development Life Cycle.

• Utilization of the different perspective of a team member by the team leader

• Development of a draft proposal through a cooperative effort

• Open-minded attitude of proposers to the ideas of other team members

• Production of a deliverable that truly stood the test of time

In general, our implementation of Excelerator was a very pleasant experience, and we will be sharing more examples in later chapters. The story related here illustrates the flavor and tone of that productivity tool’s incorporation into our environment. Indeed, each individual productivity improvement really does depend on the product, the organization, the existing procedures, the expectations of users, and the complexity of the implementation.

The Management Perspective

While the interproject team is busily preparing all these handsome packages, you may find that, as was the case during the gathering information phase, your management may express impatience. In the previous phase we advised that you should insist and even fight if necessary to ensure you had the planning time. During this phase, you are in a more favorable position because it is possible to accede to their demands without relinquishing anything that you need to accomplish your objectives. What your management is searching for and needs to satisfy their management is results. Fortunately, you can provide concrete and tangible deliverables such as the Gantt charts (and numerous associated reports upon request), standards, and roles and responsibilities, to name but a few.

Since the very fiber of every manager’s daily life consists of plans and reports, they should be able to relate quite nicely to the products your team is developing. In fact, even before the team develops its first deliverable, you will be able to provide them with agendas for and minutes from each project team meeting. Thus, they will not only be informed of your activities and progress, but also be reassured that resources are not being wasted. You should have no trouble politely requesting and insisting upon several months for this phase. Remember, though, even if you have an option to do so, do not get caught up here for too long. Keep the process moving.

Optimization of Opportunities

In term of progress there are undoubtedly many ways that you can get stuck, and we will continue to make you aware of the perils as well as offering techniques to avoid hazards. Intrinsic to our philosophy for changing your environment is the concept of optimizing situations and resources and even the possibility of generating some opportunities of your own. For example, we believe you can direct the implementation in a manner that will result in a series of successes. Searching for instances with high probability of success and then actualizing them has the obvious benefit of gaining tremendous support from management and the user community. We mentioned this idea in the previous phase during our discussion of setting a course in the data management example. In that case, we explained the various reasons that we chose to begin our phased implementation with the interfaces. When you are directing your project team to develop a schedule of activities, you must search for similar opportunities.

Suppose you are implementing Excelerator and you know a systems analyst who is an expert in structured systems analysis, and who has expressed tremendous interest in trying an automated tool for system definition and design. You are also aware he works on a new project that is about to begin development. There may be many other options available to you for the initial implementation, but unless you get a management directive to do otherwise, you should seriously consider beginning with this one. Your potential user is enthusiastic and well trained, and the timing for his project is optimal. You will have many similar opportunities throughout the change process; be open to them and act on as many of them as possible.

There is another subtle facet to the selection of which activities you schedule first. We have just stressed the fact that you must cast about for successes. But you must also consider just as carefully the speed of delivery. In other words, you may be presented with several options, each with a high probability of success. One can be delivered in a few months, while the other may take a year. It may even be true that the one that will require a year is the most visible project in your organization. Take, for example, the enthusiastic and well-trained systems analyst described above. Maybe his project’s plan has the first release scheduled for 2 years from now. However attractive an option may be, if it has a time frame as long as this, you cannot afford to select it. Remember the major initial reservation on the part of management and users alike: there was no immediate personal relief for any existing problem.

Even though you have carefully chosen the target area as well as the tool, you have successfully sold your management and users, and you have begun your implementation prudently by gathering information and planning, you cannot ever afford to lose sight of the fact that this is still a tomorrow proposition. The sooner that you can make tomorrow today (even with one intermediate deliverable), that is the moment when the hardest task of your implementation will be accomplished. Indeed, the remainder of the change process will be finishing the implementation, which will surely require years. However, your chances of success will be excellent.

Summary

• Due to the time involved and the long-range ramifications, you must provide strategic and tactical plans as well as a detailed implementation plan.

• The plans will be developed by the interproject team; this is the first arena in which you may well face political opposition.

• To avoid group gropes you must begin the preparation of every deliverable with a draft document supplied by your group.

• Some of the most common outputs of this phase are Gantt charts, dependency diagrams, standards, and naming conventions.

• In order to keep the change process progressing, you must search for successes that will result in speedy delivery.