7. Take Advantage of Opportunities

The change in the nation’s demographic structure is not just a temporary phenomenon related to the large size of the baby-boom generation. Rather, if the U.S. fertility rate remains close to current levels and life expectancies continue to rise, as demographers generally expect, the U.S. population and workforce will continue to grow older, even after the baby-boom generation has passed from the scene.

—Ben Bernanke

If you decide you are interested in working, will jobs be available? The answer depends partly on what happens in the labor market, partly on the attitudes and policies of employers, but largely on your own attitudes and initiative. As a boomer professional, work will be available for you, if you sell your experience, knowledge, and skills effectively. Whether as an employee or as a free agent, the opportunities will be out there for you, but you will need to seize them.

Employers traditionally have expected boomers to wind down their careers and retire by age 62 or 65, rather than extending their working careers for five or ten more years as many boomers would like to do. Companies expect older workers to make way for younger talent to be developed and advanced into larger jobs. They seek to maintain an orderly flow and development of talent through their organizations and their decisions are sometimes influenced by age bias.

Ironically, some employers and economists are today worrying that too many boomers will retire in the decades ahead, leaving behind job vacancies that cannot be filled by qualified workers. They worry that specialized knowledge and experience will be lost as key individuals retire. They worry that the generations replacing the boomer generation will not be large enough or capable enough to meet future needs. The resulting workforce crisis, some believe, will impede company performance and slow economic growth.

Even with immigration, more women in the workforce, off-shoring, the impact of technology, and extending the working lifetime all layered together, there still may not be enough people to get us there.

—Valerie Paganelli, Watson Wyatt consultant

However, there may be no crisis at all. Boomer managers and professional and technical workers may not retire early; they may stay in the workforce and simply be older. Regardless of changing economic conditions, the labor supply and demand marketplace tends to find a natural balance. If a demand for talent exists, boomers will be attracted to jobs that are unfilled, as will people from different occupations and qualified immigrants.

The demand for talent may be adjusted by redesigning work itself, better tailoring work to available talent, eliminating work through technology and productivity enhancements, or outsourcing work to regions or countries where talent is available. Balancing supply and demand may mean higher wages and more attractive terms and conditions for work. It also means the coming crisis will be worsened if we unduly restrict immigration of high-talent workers with the skills that are in short supply.

By 2010, the number of people ages 55–64 in the U.S. population will expand by 52%. If boomers leave the workforce as expected there may not be enough people to do the work. However, if a substantial number of boomers remain at work, such a crisis would be averted. Combined with the Gen X talent currently in the workforce and the Gen Y talent that is moving into the workforce, boomer talent can bridge any transitional shortfalls.

As a boomer professional, the aging of the workforce presents to you a great opportunity rather than a problem. The retirement of some boomers, combined with creation of new jobs in the economy, mean greater demand for your skills as a boomer professional. If a talent crisis develops for employers, you will have more opportunities to stay on at work or to shape jobs that match their needs with your skills and interests.

Even today, two in five men and three in ten women in America ages 55–64 who have pension income are also employed. A Government Accountability Office (GAO) study observed that potential skill gaps from impending retirements and a slowdown in the growth of the labor supply are likely to make older workers a resource of growing importance.

As discussed in Chapter 2, “Consider Flexible Work and Retirement,” surveys indicate that boomers are more likely than the previous generation to remain in the workforce. As a boomer, you may choose to stay in your current career or move into a different line of work. You may stay with your current employer or join another in full-time, part-time, or free agent roles. Projecting such changes in workforce participation five or ten years into the future is difficult because boomers such as you will make decisions that will define future trends.

None of this is automatically obvious to employers. You and your colleagues should encourage employers to accept and adapt to a workforce that includes more persons in their fifties and sixties. You and your colleagues should press for more flexible work arrangements, customized pay and benefits, training and development, and other practices that will attract and retain older talent. As free agents (entrepreneurs, consultants, contractors), you’ll need to work out arrangements that meet your needs as well as your clients’.

Few organizations are prepared for the repercussions of this exodus, both in terms of the experience and knowledge that will be leaving and the new population that will be entering.

—Miller and Katz

This chapter provides information and insights on the opportunities that these perceived talent shortages will create for you, as a valued professional, manager, or technical worker. You will learn about the boomer workforce and how the overall workforce will change if more boomers stay at work. This chapter also prompts you to think about whether your particular experience and skill sets will be in demand—and whether you have knowledge that organizations value and fear losing. You may consider the opportunities resulting from economic growth (new work) and the open labor market that characterizes our economy. Finally, you’ll consider obstacles that you need to overcome and the key choices you can make.

Concern about impending boomer retirements arises from the fact that the boomer generation is extraordinarily large in comparison with the generations before it and following it. The boomer generation is indeed the largest ever born in America, with 75.9 million births in the years 1946 through 1964. It was nearly 18% larger than the previous generation.

However, younger, subsequent generations are not as much smaller as many people think and therefore the talent shortage will not be severe. Generation X, following the boomers, the “baby bust” generation, is often cited as being 16% smaller. However, as noted in Table 7.1, Gen X is usually defined as embracing births between 1965 and 1976, or 12 years. If it is extended to match the 19 years of births included in the boomer generation, it is only 8% smaller. Gen X talent have been in the shadow of the boomers for a long time, waiting for boomers to make way. Gen Xers are likely to be well prepared to fill managerial, professional, and technical jobs as they are vacated by boomers.

Similarly, Generation Y, the “echo” generation or “millennial” generation (because it began entering the workforce at the turn of the twenty-first century), is larger than Gen X and is nearly the size of the boomer generation when the years of births are again expanded to be of comparable duration. This generation (ages 6–24 in 2008) has extraordinary talents, and many individuals are capable of accelerated development and larger assignments as boomers withdraw from the workforce.

The changes in the workforce, as in American culture, are slow to evolve. Generations are not distinct, with clear bright lines based on years of birth. In fact, many of the boomers born late in the generation have more in common with older Gen X members because of the social environment and experiences they grew up in (they were too young to remember Vietnam or the JFK assassination). Similarly, the line between Gen X and Gen Y is fuzzy. As discussed in Chapter 8, “Engage Younger Generations,” these generations have much in common and differences are often exaggerated in importance. In her book, Generation Me, author Jean Twenge addresses characteristics of the baby boomers’ children, born from 1970–2000, which blends Gen X and Y. It is good news that all three generations prominent in our workforce today can share common attitudes and values, value their differences, and thereby work together effectively.

Most of the studies that foresee labor shortages in the future assume that retirement patterns will be unchanged going forward; that is, that people will retire at the same age even as life expectancy and the ability to work longer go up.

—Peter Cappelli, The Wharton School

The workforce is made up of all persons who are working or looking for work. Past experience suggests that the 55 and older age group, which has typically had lower participation rates than younger age groups, will lower the overall labor force participation rate as it grows, leading to a slowdown in the growth of the labor force. Further, as they retire, the over-55 set will drive up health care costs and strain the fiscal strength of Social Security.

Actually, the U.S. workforce is projected to grow by nearly 15 million persons from 2004–2014, about 1% per year. This would be about 1.5 million or only .2% fewer people than during the 1994–2004 decade. The workforce won’t shrink in the decade ahead; it simply won’t grow as rapidly as the economists believe is necessary to support their targeted economic growth. The unemployment rate is expected to slow down to 5.0 percent in 2014—0.5 percentage point lower than in 2004.

Participation in the workforce varies with the life stages of the population, as reflected in Table 7.2 and as follows:

• Young people, under age 25, are slow to enter the workforce because they are engaged in education. Their delaying working in order to gain education may be a good thing, yielding higher skilled, more valuable workers. Employers accordingly have a direct stake in the access to and quality of education in America.

• Persons age 25–54 are most likely to participate in the workforce. Women have entered the workforce in large numbers and their participation rate has leveled off to nearly that of men. However, there is a recent trend for fewer men to participate.

• Persons age 55 and over are likely to withdraw from work or work fewer hours.

Bureau of Labor Statistics projections include a continuing gradual increase in labor participation by mature workforce (55 and older) based on past trends. However, because of factors addressed in this book, the participation rate will likely increase more than this, with the effect of retaining substantially more talent in the workforce. The increased participation rates will be higher due to better health, increased longevity, desire to stay at work, and the need for income and asset-building. Any increase in the retirement age of boomers will have a large effect on labor supply because the group is so large.

Compared with all other age groups of the labor force, the 55-years-and-older group has the most potential to increase its labor force participation rate further, and that may contribute to an increase in the growth of the labor force in the future.

—Toossi

Workforce participation by boomer women has been steadily increasing, a trend expected to continue in Gen X and Gen Y, although it will likely level off. After dramatic increases in the boomer generation and participation by women over four decades, the workforce today is comprised of 46% women and 54% men. In the next ten years, these percentages will shift to 47% women and 53% men. Among older workers, there is a trend for men to be more likely to leave the workforce. Among boomer professionals, we may expect women to stay at work longer—given their longevity, health, and the need for many to earn income and save for retirement. In many cases, they also began their careers at ages older than men.

Even after all the baby boomers have exited the labor force, the increase in life expectancy and decrease in fertility rates will result in an aging of both the population and the labor force.

—Toossi

The net effects of the changing participation rates and the sizes of different workforce age groups will be profound. As shown Figure 7.1, by 2014, the workforce will have a much more evenly balanced representation by the different age groups than today.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

The double effects of the larger number of persons who are older, plus the higher labor force participation rate among them will make over-55 workers a significant and permanent segment of the workforce. Workers over age 55 will no longer be perceived as those few who did not retire, but rather as a natural and expected part of the workforce.

As workers over age 55 remain in the workforce, they will become more visible, will leverage their skills and knowledge to stay at work, and will inevitably be working side by side with younger workers. The substantial number of older workers and the relative balanced size of the age groups will promote greater understanding and respect among workers of different ages. Organizations will ultimately adapt to age diversity, just as they adapt to gender and race diversity.

Your opportunities to continue to work after age 55 are likely to be abundant if you are a boomer in a managerial, professional, or technical occupation. You are likely to have skills and knowledge that employers most want to retain, tap in creative ways, and develop further.

As boomers stay on at work, the quality of the workforce will be sustained and enhanced by the retention of older workers who are highly experienced and trained. This will be particularly important in industries and occupations that rely on critical professional skills and knowledge. In addition to their work, they will also facilitate transfer of this critical knowledge to others and mentor younger talent in their development.

Table 7.3 shows boomers’ large share of our population and the scope of the challenge and opportunity to engage boomers in work rather than full retirement. In 2005, managerial, professional, and technical occupations included 19 million boomers, approximately 40% of the total in the U.S. workforce.

The opportunities are driven not only by the need to replace retiring workers, but also by a gap between current labor demand and a projection based on new jobs required for economic growth. The needs will be greatest in two key groups: managers, who tend to be older and closer to retirement, and skilled workers in high-demand, high-tech jobs. Older boomer professionals are more likely than most workers to have pensions, personal savings, and other retirement assets, permitting them to choose to retire. However, they are also more likely to enjoy their work and spend their earned income.

Economists note that higher-income individuals, generally managers and professionals, may have more motivation to remain in the labor force, because their opportunity cost of retiring is greater than that of workers who earn a lower income.

Even though the Gen X “baby bust” cohort is smaller, the number of graduates from colleges and universities who are the new knowledge workers has continued to rise year after year. In fact, a larger share of Gen X workers are graduates because they had the opportunity to attend college. There were roughly 930,000 bachelor degree graduates per year in the 1970s when the peak of the baby boom was of college age. At the lowest point when the baby bust cohort was college age, there were 1,169,000 graduates per year. Peter Cappelli, a professor at The Wharton School, noted that Wharton did not cut back the size of its graduating class when the baby bust cohort came through. Neither did most institutions of higher education.

There are likely to be ample college graduates in most professional and technical occupations. Colleges today are going beyond traditional college age students, attracting many older persons who are returning to school to earn degrees or improve their skills, knowledge, and qualifications. Colleges and universities are becoming more attractive by becoming more accessible, with distance learning and more flexible programs.

To make the most of the opportunities available during this transition, you should seek out the specific occupations and specific industries where shortages are most likely to occur. Look for jobs that require skills and knowledge that match, or are close to, those that you have developed and mastered. When you were a young professional, you may have sought to be broad and flexible, so as to adapt to opportunities and/or progress into management in the long-term. As a boomer, you may prefer to develop a specific specialty that puts you in the highest demand classification.

Some organizations are concerned that they will lose specialized or proprietary knowledge when boomers walk out the door. Employers feel that critical human knowledge and capabilities are at risk of being lost in such areas as petroleum engineering, nuclear power plant operation, international trade, manufacturing processes, product design, and engineering. These fields require the development of talent over a long time, including knowledge, experience, and specialization.

Additionally, there is the risk of losing organizational knowledge as managers, project managers, and others retire without developing their successors. This includes knowledge of the social culture, the people (who knows what, who knows who), and how people collaborate and share knowledge to get things done. It also includes structural knowledge—the organization’s processes, systems, and procedures—how decisions get made, resources get allocated, and results achieved.

The risk of knowledge loss may be exaggerated in many situations. Traditionally, employees have retired and taken their knowledge with them. This has always been a risk for employers. Yet employers have been encouraging older workers to leave through restructuring, early retirement incentives, and so on. This shows disregard for any special knowledge or skills they may have had that were lost when they left.

Companies are typically leaner than they once were and they lack the depth of talent to replace retirees immediately with qualified talent. Since the 1980s, many have paid less attention to preparing talent to fill vacated roles and to give them the working knowledge they need from those leaving. Companies used to have more flexibility and time to develop future talent. In those old days, some talent-deep organizations sought to have at least two ready backups for key positions and these high potentials were often themselves 40 or 50 years old.

Retention of knowledge is vital to sustain innovation, which most often builds on expertise, past experience, and learning. It is also vital to sustain the capacity for growth, to improve efficiency, and restrain costs. Overall, knowledge is a source of competitive advantage in an industry.

Almost two-thirds of respondents to a survey by Delong said that retirements in their organization will lead to a brain drain. However, the issue did not seem to be on the front burner, as studies revealed that fewer than one in four respondents said the issue is strategically very important for them today. Most organizations intend to deal with the looming wisdom withdrawal when the time comes that it is a pressing issue.

You may want to help your organization assess its risks and find solutions for knowledge retention. What can you do? Here are some suggestions:

• Discuss risks and solutions through informal discussions with colleagues or business line managers.

• Survey senior specialist line managers about knowledge areas that may be at risk.

• Survey or personally debrief employees when they terminate or retire.

You may also help enable knowledge retention in your organization, joining in an existing effort or starting one up:

• Foster informal knowledge-sharing networks in high-risk areas.

• Identify informal knowledge networks and use of web-based knowledge management tools.

• Establish formal knowledge management systems (web-based tools, inventories).

• Participate in or conduct training programs on knowledge sharing.

• Mentor and develop younger persons to help them engage in knowledge sharing.

As a boomer, you need not consider yourself to be competing with younger workers, but instead complementing them. The most effective way to retain and use the experience and wisdom you have developed is to stay and contribute, and over time, share your knowledge with others.

Occupations that face critical shortages include registered nurses and other health care professionals (for whom boomers will be increasing the demand for services), teachers, engineers, scientists, and technicians. Labor supply gaps may develop, but are filled by the natural and inevitable dynamics of the labor market. Supply expands to meet market demand, as long as it is an open market, qualifications requirements are adaptable, and wages rise. It may take a long time, but the supply and demand for talent will usually balance out. Talent is attracted to fields where jobs are available.

Peter Cappelli defines a labor shortage as essentially an employer’s inability to fill jobs at prevailing wages. Shortages may be corrected if the will is there to attract talent. For example, he suggests that the prolonged shortage of nurses in America might be corrected through an upward adjustment in pay. However, health care employers have not had the resources or the will to make nursing pay sufficiently attractive to increase the supply. Other economists have also argued that the competitive market should be allowed to raise compensation rather than adopt policies that keep labor costs low.

It’s tough to say there is an absolute talent shortage until there is full employment. The American economy has experienced low unemployment, but never full employment. And when unemployment falls, employers typically have to compete more aggressively for talent, by raising wages or otherwise making their jobs attractive. In the years ahead, we may expect close to full employment of talent in a certain few occupations. We can expect the market to adjust accordingly.

Employers can also attract talent from other occupations or geographic markets by making the jobs more attractive and/or increasing pay/wages. For example, companies needing IT talent drew from allied fields, such as engineering and mathematics. The accounting profession, facing chronic shortages of trained talent, has turned to recruiting graduates in liberal arts and other fields, focusing on their aptitude rather than their subject knowledge of accounting. Over a longer period, young people migrate toward occupations that represent the greatest opportunities. Educational institutions are typically slow in making changes in their enrollments or curricula to enable workers to move into a high-demand field, but ultimately the migration occurs.

When there are talent shortfalls, employers may also redefine the demand for talent by redesigning the work, adopting new technology, or outsourcing the work. Outsourcing the work to contractors shifts the worries and responsibilities to another business that makes it their focus. Information services firms (for example, IBM, EDS, CSC, and Accenture) build expertise, establish technical systems, and manage processes with costs that would be difficult and costly for a user company to match. Employees of the outsource vendor are “core” to the business, thus providing stronger identity and career opportunities.

Immigrants, particularly in professional and technical occupations, have the potential to fill future gaps. As a result, such immigration is a benefit to our economy, not a threat. Talent has become a global market—and it moves to the economies where opportunities exist. Any shortages of critical skills may be eased in large measure by our willingness to welcome qualified talent from other countries.

Immigration is particularly important when we have shortages of specific professional or technical talent, relative to the jobs available. During the 1996–2000 periods, American high-tech businesses welcomed tens of thousands of workers with computer and software skills. Special H1B visas enabled businesses to bring in professional talent to work side by side with locally recruited talent. The flow slowed greatly when limits were set on the number of such visas and as the slowdown occurred in the high-tech sector after 2000. Another example is the great influx of nurses from other countries. A significant source of nursing talent has been the Philippines, seemingly to the point that we have prompted a shortage in that country.

There might be concern that such immigrants stay and become part of the permanent workforce, potentially contributing to higher unemployment when the economy has fewer jobs. However, the U.S. economy rarely, if ever, has a surplus of talent—particularly in managerial, professional, and technical fields. The economy has grown steadily for decades. The current talent shortages, as noted, are based on gaps relative to growth projections, not today’s jobs.

Adding talent to our workforce on short notice is difficult. Companies have failed to ensure an adequate supply of trained talent, in part because of reduced investments in training and education in recent decades (when rightsizing took management priority). It also takes time for companies to shape and execute plans for recruiting and placing professionals into local jobs from overseas. To bridge the gap, it will be helpful for boomers to remain a few years in the workforce to fill needs (and pay taxes), but the longer-term future will depend in some part on immigration of workers of all kinds.

Projections of labor requirements and possible shortages are based on assumptions of economic growth. The Federal Reserve Board projects that annual economic growth over the next decade will fall to less than 3%, down from 3.2% annual gains through the 1990s. Expectations of a slower growth rate are based on assumptions of slower economic activity in housing, less capital investment and productivity improvement through IT applications and process improvements, and slower growth in consumer spending. Business cycles themselves have a marked impact on the rate of economic growth. The federal budget, the demands of rising costs of federal entitlement spending (for example, Social Security and Medicare), the budget deficit, and growing annual costs of interest on debt, are among the factors that adversely affect economic growth.

Slower economic growth may not be such a bad thing, even though we have become accustomed to making the economic pie bigger and bigger. It does mean slower tax revenue growth. It also means fewer new job opportunities for American workers and ultimately lower standards of living in America. But it may also ease workforce shortages.

The essential fact is that changes in economic growth, reflecting business cycles, determine labor demand, not demographics and labor supply. It is the number of jobs, not the number of persons in the workforce that reflects and drives economic growth. The workforce includes both people with jobs and the unemployed. The workforce is highly adaptable and constrains economic growth only if the economy is at full or nearly full employment, and this is rare.

Economic growth also depends on productivity growth—expanding the overall product faster than the workforce. Capital investment, productivity improvements, and technological innovation have driven much of our productivity growth since the 1990s. This will continue, unless dampened by high oil prices, high interest rates, or other adverse factors.

Employers often feel that there is a time for everyone to leave—to retire, to move on, to make way for younger folks. Age was once a convenient marker for the career cycle, including retirement timing (at age 62 or 65). Management succession plans and performance evaluations once included age as a defining factor. Mandatory retirement used to allow employers to say goodbye without regrets on either side.

However, times are changing. Discrimination in employment has been prohibited under the ADEA of 1967 and subsequent amendments. Mandatory retirement at any age was banned by federal law in 1986. Great progress has been made in eliminating race and sex discrimination, and age discrimination is fading away gradually. As long as there were few older persons in the workforce, there was little social pressure to change practices or attitudes.

A dynamic labor market gives more flexibility to boomers and to companies—to permit experienced talent to fill vacancies. But at the same time, an organization has the opportunity to be a more stable and attractive employer by minimizing the churning (loss and replacement) of its talent. When necessary, companies restructure and reduce the number of higher-paid jobs, many of which are held by older workers. Age discrimination may occur, but is not usually intentional.

Age distributions vary widely among companies—some are young, some have older profiles, typically reflecting peak hiring periods and retention. State Farm, IBM, and other large companies have actually brought their average ages down through aggressive changes in their organizations and workforces. Today’s dynamic organizations shape plans with different staffing models to fit business needs in different segments of the business and workforce. Some segments have higher turnover, some have older, longer-term staff, and some have more contingent/short-term staff.

The baby boom has brought us a tremendous number of persons over age 50 who want to continue at work and who refuse to be treated as less capable or desirable than others or than they ever were. Boomers expect others to recognize that they still are energetic, creative, knowledgeable, productive, and otherwise capable of staying on at work and performing effectively. If they are not so recognized, they expect the opportunity to make their case, to persuade managers, and otherwise overcome obstacles that are not directly based on age, but are subtly so.

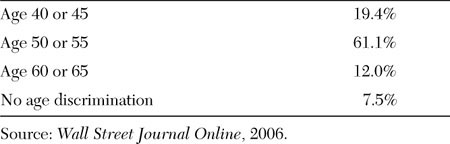

Even today, age bias begins to be apparent in organizations for employees between the ages of 50 and 60. A survey of 294 senior executives by the Association of Executive Search Consultants found that age discrimination begins to be apparent as early as age 40, as shown in Table 7.4.

If boomers want to continue to work instead of retiring abruptly, they will need to overcome the obstacles of biased attitudes and employer practices. Boomers will survive longer, be in better health, will stay active, and will make their presence known.

Cultural stereotypes, often reflected in fashion and media, are slow to change. American culture is still youth-oriented. Television producers target the age 18–35 demographic group. Ironically, while there are widely held stereotypes of older persons, there is typically no such bias against individuals who are known well and respected by coworkers on a personal basis. As with other forms of prejudice, attitudes become more positive as people get to know members of the other group better. Encouraging interaction among generations helps reduce ageism.

The age of persons is becoming more difficult to judge by their appearance and behaviors. Boomers have adopted all sorts of means to appear younger—by physical appearance, dress, behavior, interests, or fudging their resumes. This does not reduce bias, but merely avoids it. We believe boomers should demonstrate that age simply isn’t relevant. As a boomer professional, you need to show that you have what it takes and that you expect to be treated with the respect and fairness that you deserve.

The following bolded sentences are persistent attitudes toward older workers that have an adverse impact on their opportunities at work, accompanied by suggestions for you to overcome these obstacles.

“Boomers don’t have current skills and knowledge.” When professional workers retired in the previous generation, few pursued work after abrupt retirement because of their lack of portable skills. As their careers evolved within a company, most became qualified only for specific, specialized jobs. Others were the prototypical managers in gray flannel suits who “knew the organization” and whose skill sets were often job or company specific. Most boomer professionals have developed more portable skill portfolios. Most remember reading What Color Is Your Parachute? (Bolles, 1972), which promoted self-analysis, skill development, and self-reliance in career planning. Boomers have typically continued to develop and use their talents, believing that career planning and development is key to success—and many enjoy support from their organizations. As a boomer professional, you should develop an adaptable portfolio of skills and knowledge as your critical asset in finding the work you desire.

It may be that older workers were educated long ago, but this does not mean that they are out of date. Further, they do not necessarily have difficulty learning new technology applications and other practices. As a boomer professional, you should, of course, pursue continual learning to keep your skills and knowledge fresh and in tune with demands. Education, company training, certifications, and personal learning all are available to professional employees. Focus on the specific knowledge and experience that are most relevant to the work you want to pursue. You need to emphasize your current expertise in your resume, your conversations, and at every other opportunity.

“Boomers are less flexible, less capable of change, and favor the status quo more than younger persons.” A common attitude is that boomers don’t fit the more contemporary, informal, and networked organizational culture, and they are the first to object to new ideas and the last to get on board when the organization adopts them. As a boomer professional, do you take offense to this? Rigidity and resistance occurs among workers of all ages but is least likely to be characteristic of boomer professionals who are eager to stay active in work, knowing full well of the changes occurring around them and expected in the future. Show that you are a supporter, enabler, or leader of change—emphasize your experience and accomplishments. Show your understanding of issues that call for action and your eagerness to improve the current situation.

“Boomers are less creative and innovative.” Some organizations seem to have a “Dracula complex.” According to attorney Jonathan A. Segal, “They want newer and fresher blood, because they’re under the mistaken impression that it can bring vitality to an organization. However, experience and research show us that vitality, productivity, and creativity are not age-related at all.” As a boomer, you need to present your strengths in being creative and innovative. Your own style may suggest that you are better at day-to-day incremental innovation rather than out-of-the-box breakthrough innovations. Organizations need both.

“Older workers don’t relate well to younger generations in the workforce.” Similarly, they are perceived less likely to work effectively in teams than younger workers. Actually, the contrary may often be true. Boomer professionals are less likely to be concerned with competition for career advancement and hence are prone toward collaboration. High-performing boomers work comfortably with people having different behaviors and styles. One study showed that younger workers preferred to work for an older manager; boomers indicated they didn’t care whether their managers were younger or older. As a boomer professional, you should eagerly work with next generation talent. Collaboration is vital.

“Older workers act more slowly and do not share a sense of urgency.” Older persons are suspected of “retiring on the job,” letting others work harder to get the work done. This is also uncommon. In well-managed organizations where there is a line of sight (empowerment, accountability), reinforced by rewards and performance management, professionals of all ages are expected to get the job done in a timely and quality manner. Where there are differences, the patience that some older persons may have helps balance the more impulsive tendencies of some younger persons. As a boomer professional, you can demonstrate that you can sense the pace and rhythm of an organization and you are committed to helping achieve objectives on a timely basis. You will carry your weight.

“Older workers are more likely to dominate senior positions.” As a result, they are seen as blocking opportunities for development and advancement of younger talent (representing a “gray ceiling”). Yet few organizations today hire at the entry level and manage a flow of talent through the organization’s levels. Instead, most hire talent at all levels, increasingly experienced talent—and there is an age mix at all levels (age diversity is a good thing). Senior assignments and tenure in them should be based on demonstrated skills, experience, and performance—not on age. As a boomer professional, you should identify clearly what senior positions require and emphasize your bona fide qualifications and demonstrated performance. Don’t let your age be an issue.

“Older workers tend to be more expensive than younger workers, by virtue of their experience, tenure, and level.” Older job candidates are seen as too qualified for the positions available, making them (supposedly) more costly and prone to boredom or disruption to the organization. In some firms, “maturity curves” have been used to pay engineering talent, paying individuals based on tenure and age, with the assumption that learning and skills increased early in their careers. Today, professional and managerial jobs are typically paid based on the value of the job (the work performed, level, impact, and so on), as well as the market value of the individual’s talents (competitive pay for experience, qualifications, and so on). Hence in a well-managed organization, there should not be excessive pay given to older professionals and managers, but assignments and compensation should reflect the value that individuals provide. As a boomer professional, you should encourage managers to pay fairly—age itself is not a reason to get compensated more or less.

“They need more health care benefits and services, driving up health care costs.” All individuals who have accidents, become ill, or suffer chronic conditions also incur extraordinary costs. The key idea of group insurance coverage is the pooling of cost risk to make sure everyone is covered. Excluding older workers as a class is hardly a thoughtful response. Government regulations permit employers to provide health benefits based on a common dollar value to all employees, even though this puts a burden on the individuals of any age who have extraordinary needs. As a boomer professional, look after your health care insurance needs—and, if you can, stay well, healthy, and fit!

It comes down to being between 30 and 35, you’re fine, no problem. If you are younger than that you have to work hard to prove yourself. If you are older than that you have to work hard to convince people you still have what it takes. Everyone has to learn new things because new technologies come out every six months.

—P. Anderson

Surveys by Skladany and Sumser indicate that 65–70% of workers age 50 and over experience damaging age bias in their organizations. Employers indicate that they feel such opinions are exaggerated. Business and employer groups say there is no significant age bias anymore and that most employers act in compliance with laws. Yet older workers believe they are unfairly treated relative to younger workers. One study found concerns in these areas:

Another survey, conducted by Reynolds, asked 1,207 technology employees whether they had experienced workplace setbacks—layoffs, being passed over for promotions, missing out on bonuses, and so on. Of those responding, 40% said that age discrimination is a significant or widespread problem in the technology professions. However, another 40% disagreed. Techies younger than 35 were twice as likely as those over 45 to dismiss the age issue as insignificant. The study also noted that age discrimination sometimes also cuts the other way when young techies complained that they are perceived as too young and inexperienced.

If you feel you are unfairly treated, even with all of your own best efforts to remove your age as a consideration, you have the legal right to protest discriminatory actions under state or federal laws. In fact, it has never been easier for an individual to initiate a complaint process. In practical terms, however, personal influence may be more effective in opening up opportunities.

It is typically difficult to prove that adverse actions were age-related and intentionally so. ADEA and state statutes have not significantly reduced age bias and discrimination. Most EEOC complaints are resolved in favor of employers, as age discrimination is difficult to prove (60% are found to have no reason to believe that discrimination occurred). In many cases, individuals who filed did not provide satisfactory evidence to support formal charges. Only 10% of ADEA charges result in any kind of benefit being paid to the individual complaint. As a result, age discrimination is assumed to be under-reported. Many aggrieved workers never file charges and simply move on in their lives.

We all aspire to live to be old and consequently we all must work to create a society where old age is respected, if not honored, and where persons who have reached old age are not marginalized.

—Richard Butler

As a boomer, you need to allay fears an employer may have about older workers by showing energy, flexibility, reasonable pay expectations, up-to-date skills and qualifications, and a reasonable explanation of why you decided to change jobs or careers. Here are some suggestions:

• Expect fair, unbiased consideration. Expect proper, uniform job interview questions, without any relating to age. Expect consistency of all hiring and promotions decisions regardless of age. If you experience difficulties, look for employers that state that they value diversity.

• Simplify your resume. Shift your emphasis to your value, not your age and the many jobs you’ve held. Don’t list every single job you’ve ever had, and emphasize your major accomplishments, not the years you spent in various jobs.

• Keep your skills and qualifications current relative to those valued in your field. Highlight specialty skills, technological proficiencies, and recent training that reflect enhanced levels of competence. Use contemporary, rather than outmoded language, to describe your experience, your accomplishments, and your interests.

• Keep a good relationship with your manager and colleagues at work so you’ll know what is going on and you can comfortably talk with them about your interests and concerns.

• Think of yourself as a member of a skill group rather than part of an age group. Emphasize the need of an organization to have diversity of ages and experience to facilitate performance.

• Make a strong case for why someone should hire you. Describe your characteristics that are important to a hiring manager. Differentiate yourself from others based on the unique qualities, work ethic, and commitment you bring to the workplace.

• Keep a log of all occurrences you think might be construed as age bias. Also save emails, memos, and other documents as support for your claims, if they become necessary to support a complaint.

The potential shortages of managerial, professional, and technical talent present opportunities for you as a boomer. Whether you take advantage of the opportunities depends on your choices as you pursue your career. Here are some things to consider:

• Understand how the market is changing, what skills are in demand, what the future trends and emerging opportunities are, and how you might fit in. This calls for you to be market savvy—networking, listening, and learning about shifts in jobs, talent movement, job opportunities, and the “best” employers.

• Understand the important skill, knowledge, and experience requirements and match your talents with them. Focus your attention on opportunities that look like they are a good fit. Make the most of your strengths—your knowledge and experience that are relevant—and translate your experience into value that is relevant to the opportunity.

• Figure out your strategy for working. Consider your options and focus on your preferred working arrangements: Stay in your current job? Redefine your job? Move to a different job—in the company or another? Or be a free agent, as a consultant or contractor?