6. It’s Your House: Social Media Marketing Protects Your Reputation

And in one, fell swoop, the chocolate giant learned what every company needs to know: Social media presents a need for a different type of crisis communications. The company created the fan page on Facebook so its fans could talk about their favorite Nestlé products and see announcements about new candies. Waking up one day to see a bombardment of complaints about unethical practices wasn’t what the company had in mind for its social media efforts. They weren’t prepared.1

The comments were part of a Greenpeace campaign against Nestlé that launched that same week, following a report that said the candy giant was buying palm oil from a supplier that was responsible for deforestation in Indonesia and the deaths of thousands of orangutans.2 Comments from page visitors ranged from why they quit buying Nestlé products to displaying altered Nestlé logos, such as retooling the Kit Kat logo into Killer (see Figure 6.1) or stamping bloody orangutan prints on the traditional corporate logo.

Figure 6.1. Protesters on the Internet had a field day using their graphics skills to retool the different Nestlé logos to draw attention to their campaigns.

Pop Quiz: If you’re a large multinational brand that is being hammered by thousands of activists and protesters from around the world, what would you do?

A. Have an open dialog with the protesters and organizers about their concerns.

B. Launch a full-out attack with attorneys and sternly written cease-and-desist letters.

C. Nothing.

D. Turn the response over to a junior-level person who was tasked to handle a community page on the world’s biggest social network.

Not too surprisingly, choices B and C are the ones most companies follow, which only makes the problem worse. But Nestlé chose option D. It’s most memorable response, and one that is often cited as a big “Don’t” in crisis communication seminars, was “...we welcome your comments, but please don’t post using an altered version of any of our logos as your profile pic—they will be deleted.”

This set off a huge thunderstorm of responses. The Nestlé spokesperson got into an argument with fans who were upset that Nestlé focused on the nitpicky details of an altered logo, rather than discussing the more important issue of Indonesian deforestation and animal slaughter. Here’s what some of the comments and responses started to descend into:

A Facebook Fan: “Not sure you’re going to win friends in the social media space with this sort of dogmatic approach. I understand that you’re on your back-foot due to various issues not excluding palm oil but social media is about embracing your market, engaging and having a conversation rather than preaching!”

Nestlé: “Thanks for the lesson in manners. Consider yourself embraced. But it’s our page, we set the rules, it was ever thus.”

Another Facebook Fan: “Freedom of speech and expression.”

Nestlé: “You have freedom of speech and expression. Here, there are some rules we set. As in almost any other forum. It’s to keep things clear.”

A Third Facebook Fan: “Your page, your rules, true, and you just lost a customer, won the battle and lost the war. Happy?”

Nestlé: “Oh please...it’s like we’re censoring everything to allow only positive comments.”

And it only got worse. After hundreds of people expressed their outrage about the extinction of orangutans, the page administrator responded, “Get it off your chest—we’ll pass it on.” Messages were deleted, both from commenters and the administrator, if they were argumentative, contained altered logos, or were generally negative and nasty.

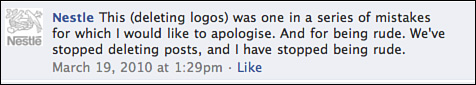

Finally, for whatever reason, the administrator realized the company was being snowed under with comments, and his own vitriol was not only adding fuel to the fire, it was also bringing in more attention as people who were leaving comments went to their own social networks and asked their friends to get involved. It finally reached its peak when the national and international media started paying attention to the Facebook fight (see Figure 6.2).

Figure 6.2. The Nestlé Facebook administrator realized he was not winning any friends and was creating more problems than he was solving. The commenters didn’t necessarily stop being rude, but the administrator did stop adding fuel to the fire.

Eventually, after two months of constant onslaught and global attention, Nestlé announced it was no longer buying palm oil from companies that destroyed rain forests, and Greenpeace declared its campaign a success.3

But the concession did not come without a price. Nestlé’s reputation was tarnished online, and the company completely lost whatever control it thought it had over its social media network. A year later, the page has more than 180,000 fans, and the activism has not stopped. Although people have stopped talking about the campaign, Nestlé only seems to use the page for announcements and not for interacting with fans. Meanwhile, every announcement the company makes is met with more statements of outrage about how Nestlé supports slavery and genocide in Africa, calling on them to cease doing trade with the Ivory Coast, and any other controversial issues Nestlé might be associated with, even on the periphery.

However, Nestlé employees are taking matters into their own hands, sort of. Some employees will post messages saying they work at a Nestlé plant in a particular city or country, but that’s it—nothing more than “I work at Nestlé in El Salvador” or “I work 4 Nestle Kenya.” Although this might attempt to counter the negative comments, it doesn’t make much of an impact. But the corporation refuses to engage with the complainers directly on any issue.

Although this is not a dumb choice, given the furor that arose in 2010, it’s also not a smart choice. It means they’re not really participating in conversations on their Facebook page at all, and they are giving people the chance to hit it with more negative comments. It means they have given protesters a chance to air their grievances without responding to them, which only tells the protesters this is a safe place to attack the company without any concerns about rebuttals or being contradicted.

This brand attack can—or at least should—elicit a crisis communication response from a PR professional who works to contain the negative publicity about their employer and the brand they’ve spent years creating and building.

Obviously, we don’t want your company to be a mini version of Nestlé. By anticipating negative comments, even public outcries about your company, product, or service, you can avoid much of this type of negative interaction. By understanding the nature of social conversations, their viral potential, and what it takes to inject your position into a firestorm of detractors in an effective way, you can be a savvy crisis communicator for the twenty-first century.

What Is “Crisis Communication”?

Crisis communication means different things to different people. To former crisis communicators like Erik, who was once the risk communication director for the Indiana State Department of Health, it means communication during a public emergency. More commonly known as Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication (CERC; that’s government speak for you. Why use two words when four will suffice?), it means communicating as much information as possible to fully inform the citizens of an affected area. To PR professionals, crisis communication means communication during a company crisis with the media—and increasingly, the public—through social media. This corporate crisis communication becomes necessary during product recalls, brand attacks like the one Nestlé experienced, or political crises, like a politician or business CEO-lebrity caught in a compromising position with someone who is not his spouse.

CERC and corporate crisis communication require different approaches, different ideas, and two completely different types of plans. But its qualities are important to understand because they can better inform your business’s crisis communications measures. When you boil it down, CERC is basically regular public relations at a lightning-fast pace. It means dealing with the media and the public and working to put people at ease:

• In corporate communication, the first instinct is to hunker down and contain the bad news. In CERC, the first instinct is to flood everyone with as much information as possible. Neither of these is always the best choice, but they usually are the first instinct of their respective practitioners.

• In corporate communication, the negative end result is a loss of money. In CERC, it could be a loss of life. Of course, some instances of corporate communication may also be about a loss of life, such as a tainted food or drug recall, or safety problems related to an automobile. Similarly, a CERC situation could be related to a loss of money, such as during a fire or chemical spill.

• Corporate communication is often about containment, keeping as much information in house as possible to mitigate damage to the company’s reputation and avoid a possible lawsuit. CERC is often about widespread communication, trying to reach as many people as possible, so nothing is hidden from the public.

• Many times, corporate communication is the most visible response from the company with other actions happening behind the scenes, like the legal response, brand management, and the product recall team. In CERC, the communication team is there for support, communicating with the public about everything else that is going on: incident response, medical response, and cleanup. That’s because corporate communication is more about guiding the public perception, trying to manage the message people are receiving. CERC is about informing the public, keeping them up to date with what the first responders are doing, and managing the message so people can take the appropriate actions.

Both CERC and corporate communication need social media as a way to monitor what people are saying about the incident and even to respond to the public to correct misinformation and relay correct information. But you need to monitor what the public is saying and respond immediately when appropriate. You can’t rely on traditional media to deliver your message because those channels don’t operate as quickly as the Internet. Besides, traditional media is going to be a filter on your message anyway, delivering select pieces of it on their own schedules.

You Just Can’t Wait for Traditional Media to Catch Up or Get It Right

Natural and man-made disasters move so quickly that developments leave traditional media in the dust. Stories are held until the evening news and the morning paper, unless it’s big enough to warrant breaking into regular programming or one of the 24-hour news networks picks it up. The media outlets that have evolved with the times have done so using social media platforms like Twitter and content RSS feeds first popularized by bloggers to post breaking news to digitally connected audiences.

So social media is quickly becoming an alternative to traditional media—even an alternative used by traditional media—letting citizen journalists report on what’s happening around them, reaching people in their networks immediately, often before the mainstream media or the outlet’s main reporters even show up.

On January 15, 2009, Janis Krums was on a ferry on the Hudson River, when US Airways flight 1549 made an emergency landing on the river. His tweet (Figure 6.3) was the very first communication about the landing, and it had been read and retweeted by thousands of people 15 minutes before the first news reports hit the airwaves. In fact, nearly 35 minutes after Krums sent his tweet, he was on MSNBC being interviewed as a witness.

Figure 6.3. Janis Krums’s historic tweet was read and retweeted by thousands of people 15 minutes before the mainstream media reported the river landing.

Social media sites, even personal Twitter accounts like Krums’s, are breaking news before the news does. Mainstream media often has a printing and broadcasting schedule it has to follow, and they’re going to stick to it. People depend on the news being on their TV or their front porch at the same time and the same amount of time/paper every day. And unless the news is truly catastrophic, they’ll stick to that schedule without fail.

That breaking news mentality extends to companies and brands as well. Remember the Domino’s Pizza story we touched on in Chapter 5, “Make Some Noise: Social Media Marketing Aids in Branding and Awareness”? The pizza giant faced a serious crisis of credibility and cleanliness, thanks to the two employees and their disgusting video desecrating a customer’s order. The video was passed around the Internet at lightning speed—almost as fast breaking news of celebrity deaths or arrests—and the company had no time to think before the public outcry was at a fever pitch. One Domino’s Pizza spokesman said that people who had been loyal customers for as many as 20 years were “second-guessing their relationship with Domino’s.”4

Domino’s Pizza executives decided to do nothing, hoping the furor would die down, but it only grew. They stayed away from social media for two days before finally taking action, creating a Twitter account to respond to any comments and questions. They also created a YouTube video with their CEO addressing the concerns their customers had raised. Although they had been talking about their commitment to customer health and safety in the traditional media, no one on Twitter seemed to notice. The company hadn’t already been participating on the network, building relationships with customers and proving they were interested in their audience’s feedback or input to that point. The company’s traditional mindset meant it was bound by traditional media’s schedule and filter, and couldn’t reach the social media users who were making the loudest noise.

Although some social media practitioners said this 48 hours of unanswered questions and discussions hurt its brand, the fact that Domino’s Pizza took to the same networks where people were questioning the company’s commitment to customer care shows some forward thinking and a willingness to address problems head on. After almost two years of active participation on the social web through these channels, Domino’s Pizza has a noticeably better online reputation among fans and followers. They have used social media marketing since the incident. And if they’ve only used it for the one purpose—to be present in the conversation so they can better communicate with the social audience when a crisis arises—that’s a significant improvement.

While the crisis communicators are waiting for their stories to hit the media, the public is already talking about what’s happening on Twitter and Facebook. By the time the TV news talks about the story, it’s been on social media for several hours. By the time it appears in the newspaper the following morning, the events are already in their second day of discussion on social media.

The public isn’t waiting for the media anymore. They’re using social media to create and consume their own news. Anyone who wants to reach his audience, especially in times of crisis, needs to incorporate social media into a reputation management plan. This type of plan includes choosing traditional and social channels with which to communicate, monitoring mentions and brand pages on multitudes of socially driven websites to ensure accuracy and protect against detraction by disgruntled customers and building a consistent presence to offset any sudden claims or news that is detrimental to the company.

The question facing companies now is whether they will respond to the social media news or will they only wait for traditional media? The biggest mistake they can make is not to respond at all. Social media—if not the mood of the country—makes it necessary for companies to respond to crises as they occur.

When You Don’t Listen or Respond, You Get Chi-Chi’d

By now, we’ve probably scared the hell out of you, and you’d just as soon never get involved with social media. We don’t blame you; thousands of pissed-off bloggers and Facebook fans can intimidate anyone. But you can’t stay away from social media—because your customers are already expecting you to be on there. Remember Gary Vaynerchuk’s statement from Chapter 2, “It’s Not Them; It’s You!”?

It doesn’t matter if you think it’s stupid (or scary). It’s free communication, and there’s a crapload of users.

Social media users have come to expect their favorite brands to be on social media. This expectation of response and interaction has gotten so pervasive that people get upset when they don’t hear back from a company about their complaints, so they tell their friends about it, telling them about how they were ignored and their problems went unanswered.

The story of Chi-Chi’s Mexican restaurant is a cautionary tale often told to executives about what could happen to companies that don’t respond well, if at all, and take their customers for granted. Although the story of its demise begins in 2003—long before much of the movement we now know as social media took root—it still shows how crisis communications and responding to customer’s concerns are critical components of a company’s marketing and communications efforts.

Chi-Chi’s was a sit-down Mexican restaurant chain with headquarters in Louisville, Kentucky. In November 2003, a Chi-Chi’s restaurant in suburban Pittsburgh was hit with the largest hepatitis A outbreak in U.S. history, resulting in four deaths and 660 more people getting ill. But rather than deal with the problem, respond to media inquiries, or communicate with the public, Chi-Chi’s top executives avoided any contact with the news media. Instead, they issued very dry, factual one-page statements. Two weeks after the outbreak was confirmed, Chi-Chi’s COO, Bill Zavertnik, visited the site of the outbreak, read a brief statement to reporters, refused to take any questions, and took the corporate jet back to corporate HQ.

Subsequent media statements came from Chi-Chi’s parent company, having obviously been written by lawyers who were looking to avoid a class-action lawsuit. The problem is, their reactions made people extremely angry because they felt ignored and unheard, so they filed their class-action lawsuits anyway. Ten months after the initial outbreak, when it was already in bankruptcy, Chi-Chi’s was forced to close all U.S. locations and pay $2 million to settle the 60 biggest lawsuits it faced.

Who knows what could have happened if the company had been more transparent in its communication with the media and the public? Would it have kept Chi-Chi’s in business? Would it have avoided the class-action lawsuits that ultimately killed it? No one can be sure. But we do know that despite their best efforts to avoid media scrutiny, the company failed and died anyway. However, straightforward communication might have gone a long way to saving them.

Before we go on a huge rant against corporate lawyers being prevented from going anywhere near the communication office, let us first say we understand the need for corporate lawyers. But although they do important work, they should not be in charge of the actual wordsmithing, or even the response. Legalese is signal one to the public that the company doesn’t understand them, or that they don’t want the public to understand the company. The response needs to be decided on by executive management and created by the crisis communicators, who will hopefully have their finger on the pulse of the public. If you yourself don’t know what the public is thinking or wants, ask the people who do.

Talk to the salespeople and the marketing department. Let PR manage the response, give sales and marketing some input, and let the legal department keep people out of jail or from violating any laws or regulations. But don’t let them take over the public response, or you could run into the same outrage that Chi-Chi’s faced, after it offered up a sanitized, half-hearted written statement, without actually engaging their customers. Remember, you’re not going to avoid making people mad during a corporate crisis. You will make them even angrier if you look like you don’t care.

Of course, responding poorly is only slightly better than not responding at all, because it only adds to the mess. The story about Nestlé’s response to its non-fans created a bigger problem than not responding at all. And now that Nestlé has adopted a nonresponse as its strategy, you can see how well that’s working out for them now. (Hint: It’s not.)

Six Steps for Dealing with Detractors

Because dealing with detractors, even those who have every right to be talking negatively about your company, is intimidating and stressful, you can handle them with grace, humor, and honesty. We’ve told you stories of how not to handle crises in social media communications. Now let’s look at how your company should handle incidents when people talk bad about your organization online.

1. Acknowledge their right to complain.

Free speech may not be a founding principle of every country, but it certainly presides in communications online. If a customer has a run-in with your brand at any point and isn’t satisfied, she can, and often should, tell someone with the company, or even just a friend.

2. Apologize for their situation or your mistake, if warranted.

The two most powerful words in diffusing a tense situation are, “I’m sorry.” But you don’t have to claim responsibility for the situation by doing so, especially if you don’t have all the information to make that determination. Apologize for the detractors’ trouble, the situation, or their experience and ask for more information on how you can help them or make the situation better. If it turns out your company did something wrong, you can say you’re sorry for that, too. Even if your lawyers tell you not to.

3. Assert clarity in your policy or reasons, if warranted.

Sometimes people are upset about a return policy or some rule you follow that can’t be changed. It’s perfectly fine to assert yourself to someone who is being negative about your brand, but do it politely, with compassion and by supplying the reasons your policy exists. Don’t make the reasons about the detractors; make it about the betterment of every customer’s experience.

4. Assess what will help them feel better.

Comcast’s Frank Eliason answered upset customers on Twitter in 2007 by asking the question, “How can I help?” What those four simple words do is turn the power of the conversation over to the customer and let him, if just for a moment, dictate the terms of what would help. When the customer feels listened to and empowered, the company often earns credibility in his mind.

5. Act accordingly.

If you can, within your company’s policies and within reason, do what the customer says will make her happy, do it. We understand there will be instances when a customer request is either beyond your individual power to enact or is just unreasonable. But if it’s within the parameters of appropriateness, do it. Putting out the flames of a detractor’s fire quickly and sufficiently is the best way to turn that detractor into a fan. Or at least someone who isn’t flaming you anymore.

6. Abdicate.

If you’ve exhausted all reasonable means of addressing the customer’s issue and he still insists on unreasonable responses or refuses to quiet his claims, it’s okay to step away. By politely offering the solution again and informing the customer that this is truly all you can do and you are happy to do so, but you have to move on to other customer issues, the decision is on him. The great news is that if you and your team decide you’ve been fair, honest, and reasonable with the customer, but they’re being unreasonable, the rest of the audience watching the conversation will think they’re being unreasonable, too. Jason likes to say, “Sometimes a turd is a turd.” And no one will fault you from walking away.

But It’s Not Always About the Negative

We would be remiss if we spent this entire chapter talking about the negative side of the reputation equation. Protecting your reputation can take on a proactive spin as well.

Using your monitoring solution to search for mentions of your product or service will certainly help you identify the harmful conversations in which you need to participate. But it will also show you many more positive or even neutral mentions of your brand. Just because these conversations don’t have the big red flag sticking out of them doesn’t mean they should be ignored.

If putting out fires is one execution of reputation protection on the social web, then fanning the flames of good fires is another. Whether it’s dropping in to say, “Thanks! Appreciate the support!” or just answering a question someone posed related to your brand or the industry, at a minimum you will appear present and accounted for in the conversation.

Your presence in online conversations alone will cut down on a ton of potential negative conversations or complaints about your company. Socially enabled companies see a customer in need and fix the issue almost instantly. It’s not because these companies only respond to the bad. It’s because they’re present in the conversation. Company representatives chitchat with folks as well as address customer service issues. They drop in and say thank you or retweet a Twitter message that compliments the company.

They’re participating in the conversation.

If the only thing you do in protecting your reputation through social media marketing is finding a handful of positive mentions each week and reaching out to say, “Thank you,” you’re protecting your reputation just a bit.

Protecting Your Reputation Has a Technology Side, Too

Let’s say you own the best doughnut shop in Philadelphia. The local newspaper says so, and the general consensus of the public agrees. Even your competition might say, “Yep. They’re darn good.” But if you aren’t using the web and social media much, Google won’t think you’re the best doughnut shop in Philadelphia. So protecting your reputation applies to search results as well.

This is where social media and search engine optimization overlap to create a golden opportunity for your business. Two of the primary factors that help a particular piece of content rank well in search engines were how recent the content was and how many people linked to it. Recency and third-party endorsement still go a long way in capturing search engine rankings. Recency is most readily won by blogging. Blog platforms are made to help you publish content frequently, so one of those two big factors is addressed when your company publishes blog posts. Promoting those posts to attract links from other bloggers and websites helps the other big factor.

With the evolution of social search, however, Google (which accounts for 80% of the search market) is beginning to use a wider net for capturing those third-party endorsements, while delivering more customized results for each user at the same time.

Social search is another layer of information the search engines take into account when producing results, based on your social connections. These connections—your social graph—produce what Google considers more relevant results for your search query. When you type in “best bakery in Philadelphia,” instead of seeing what Google thinks are the best websites that answer that question, you now see results that include what your friends think is the best bakery in Philly. That is, if Jason is talking about your doughnut shop, it could show up in Erik’s search results.

Jason has many friends in Philadelphia, so if he searches for the best bakery, his results will be influenced by his friends’ activity on social media sites. In early 2011, Google’s top result for the query, “best bakery Philadelphia” was a shop called Imagicakes. But Jason’s top result was Termini’s Italian Bakery, thanks to his friend Bill Lublin’s review on Yelp.com.

Google search results can be further influenced by the number of “likes” a company collects on its Facebook fan page or mentions it gets in Facebook conversations. If even casual social media participation can affect where you rank in search results for certain people, then protecting your electronic reputation in the search engines is helped by social media activity.

Affecting the search engine results extends beyond using Twitter and Facebook to ratings and review sites as well. By using social media monitoring services to be aware of new reviews on sites like Yelp, Urbanspoon, MerchantCircle, or even Google Places, companies can immediately address negative reviews and even amplify positive ones to capitalize on what customers are saying about them online.

All this activity helps your company move up in the search engine results. It also helps ensure that if a blogger or online audience member gets upset and takes his or her frustration out on you online, that piece of content doesn’t rank high for a search result for your brand or company. Remember Jeff Jarvis’s blog post we talked about in Chapter 2? His Dell experience beat out the company for search engine results for “Dell” for quite some time.

You don’t want the bad outranking the good any more than you want your competition outranking you for certain keywords. Social media activity adds to the all-important factor of prominence in the search engine’s rankings. In a video about Google’s Local Search rankings,5 Google product manager Jeremy Sussmann explained prominence was determined by how well known or prominent certain business are based on sources across the web. Those sources include blogs, review sites, social networks, and more.

Putting Metrics Around Protecting Your Reputation

Protecting your reputation is just as much a function of marketing as it is of public relations. As PR cleans up a mess, the marketing department has to work that much harder to overcome it in the future. A major misstep means marketing has to go to extra lengths to convince people that whatever the earlier problem was is no longer.

This means that a tarnished reputation could become so cumbersome that the only thing that’s going to overcome it is millions of dollars. If you’re a small company with a huge problem, you don’t have millions to blow on fixing it. Chi-Chi’s had such a big problem that the only thing that solved it was selling most of their restaurants and closing down the rest, leaving only a few overseas restaurants and a packaged food division.

Obviously, protecting your reputation is worth something. At the very least, it’s worth thousands, hundreds of thousands, or even millions of dollars; at most, it’s worth your company’s very existence.

Although social media activities can be easier to measure than other mediums because of the digital nature of the Web, reputation management is much more difficult. This is because you’re using hindsight to look back at incidents and opportunities. You can tabulate the total losses by adding up all the customers who left, adding up their projected sales, and coming up with a pretty good idea of what you lost. But you can’t put math behind potential losses you avoided by being on top of the online conversation.

Let’s say you discover a serious security flaw in your software that could allow someone’s financial information to be stolen. You discover the problem, fix it, address it in the media, distribute the fixes, and weather the storm of complaints, even though no one lost any of their information. For the most part, people are annoyed, but remain customers.

How do you measure what could have been? Would you have lost 2% of your customers or 60%? Would you have been sued and for how much? You can get a rough estimate of what the disaster could have cost, but short of actually letting it run its course, you’ll never know what the end results would have been.

That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try, though. You can use the different social media monitoring tools to not only find mentions of your company or certain industry keywords, but also to measure the sentiment of those comments, and tell you whether people like, are neutral about, or dislike the name in the mentions. Figure 6.4 is a screenshot from a social media monitoring service.

Figure 6.4. Frankly, we were rather surprised to see that 3.9% of the sentiment was negative about bacon. Who doesn’t like bacon?

But with tools like Radian6, Sysomos, and AlterianSM2, the people in charge of reputation monitoring can use software to identify problems and complaints and begin addressing them immediately, rather than being caught by surprise. Some of the metrics your company should measure for your reputation management efforts include the following:

• Positive online mentions and sentiment using social media monitoring or online clipping services and data analysis

• Negative online mentions and sentiment using social media monitoring or online clipping services and data analysis

• Search engine result rankings using a search marketing rank checking tool or service

Any of these results can show you a measure of your company’s reputation. Comparing your reputation today with a year ago, or even a looking back on today a year from now, gives you benchmarks and even potential goals to improve upon or maintain.

Keep in mind that monitoring your brand reputation is not something that can be handled on a wing and a prayer, or by waiting for the perfect storm of angry consumers and consumer activists to air your dirty laundry. Savvy social media practitioners constantly monitor the sentiment and analytics of their brands and related industry terms.

In 2009, Jason wrote an industry report called “Customer Twervice: Exploring Case Studies & Best Practices in Customer Service Efforts Using Twitter.”6 He looked at the customer service efforts of eight different companies, including Network Solutions, an Internet domain and web hosting company.

Just two years earlier, Network Solutions had very low positive sentiment scores in online conversations. That is, no one liked them; customers disparaged them, complained about them, and, for the most part, had nothing nice to say. But two years later, they were, as Jason called them, “one of the best examples of reputation management via customer service out there.”

“The four things we look at in terms of our social media strategy are brand and reputation management, connecting with our customers, connecting with our community, and driving new business,” said Shash Bellamkonda, Network Solutions social media director. “The social media team is trained as customer service representatives.”

Although Network Solutions uses social media as a customer service tool (product managers will jump in and answer questions from time to time), it ultimately protects their reputation as well. NetSol is unusual, but not unique, in that the company views reputation management as a customer service function, rather than public relations. Even though the customer service department would probably not typically be called on to manage a company crisis, by responding to customer service crises, customer service representatives have managed to improve Network Solution’s online reputation in two years with one simple tool that lets people communicate 140 characters at a time.

“Our long-term goal is to have more customer support front-line people there,” Bellamkonda said. “We have 40 people on Twitter from customer support right now, but they don’t do regular monitoring. We have Twitter volunteers who engage with customers to help the social media team, but our philosophy is to train everyone else to engage in it.”

As more people use social media, whether it’s Facebook, Twitter, or any of the other thousands of social networks out there, it’s important to monitor what’s being said about your brand. If you do something wrong, be prepared for people to blast you for it. But don’t get defensive because that will become the story.

If an employee behaves badly, be prepared for news to go viral, but don’t sit quietly and wait for it to go away because the story will grow even bigger. If your reputation is already poor, start using social media as a way to improve it by listening, responding to complaints, and demonstrating your commitment to your customers.

And look at your search engine results. Do you deserve better? Are you the best, or at least in the top 5 or 10 at what you do in your area? Do you rank there? Start employing search engine optimization tactics to protect your technological reputation as well.

Protecting your reputation using social media lays a great foundation for the next benefit of social media marketing for your business: good public relations.

Endnotes

1. Elliott Fox, “Nestlé Hit by Facebook ‘Anti-Social’ Media Surge,” Guardian, March 19, 2010. http://www.guardian.co.uk/sustainable-business/nestle-facebook.

2. “Sweet Success for Kit Kat Campaign,” http://www.greenpeace.org/international/en/news/features/Sweet-success-for-Kit-Kat-campaign/.

3. “Sweet Success for Kit Kat Campaign,”http://www.greenpeace.org/international/en/news/features/Sweet-success-for-Kit-Kat-campaign/.

4. Stephanie Clifford, “Video Prank at Domino’s Taints Brand,” The New York Times, April 15, 2009. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/04/16/business/media/16dominos.html.

5. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L1ONMavPX2o&feature=player_embedded.

6. Jason Falls, “Customer Twervice.” http://www.socialmediaexplorer.com/customertwervice/.