Chapter 4. Equipping the Team

The Environment

One of the characteristics of a job that distinguishes it from others is the physical environment in which people work. Do they have the tools they need? Is the environment pleasant? Does it inspire creativity? Does it support collaboration and bring people together in a way that enables each person to be the best that they can possibly be? Does it define who they are as a team? I have been in environments that range from an office with several people packed in it, to a light, airy office with windows that opened to the outdoors in a brand new building, to a design studio environment in the trendy downtown area of Denver. I have been in more formal work environments that had mail delivery robots moving by periodically and those where people zoomed by on scooters, played foosball at every opportunity, and those where a remarkable amount of partying was a regular part of the work environment. I have had a variety of awesome labs that I have been able to design, I have worked where the lab infrastructure was shared, and have worked where we just had to cobble together whatever we could to collect user data. Through it all, one of the things I have learned is that the physical environment you create can go a long way in shaping a team identity and climate, projecting that identity to the company you are supporting, and engaging those people in your work.

Lab Space

Fundamentally, user research requires little more than a pencil and paper and an astute observer. However, the space for usability testing is more than just a tool to run user studies. It is also a powerful tool for making those studies more effective. Bringing managers, project managers, developers and others into the lab to observe users working with a prototype involves them in your work and educates them. At times it can be too successful. I remember one manager who was sitting, watching her favorite feature being used, and listening to the user saying things like, “This sucks. Who could ever think this would be useful?” She immediately picked up her cell phone, called the developer, and started redesigning the feature in real time. I had to caution her that it was worth at least seeing a few others using the feature before we wrote it off entirely. Today it is clearly also valuable to broaden the potential audience and leverage the public relations value both by streaming the studies as they are occurring over your intranet, and circulating video clips highlighting particularly interesting moments during the testing. But it is the live viewing of users that creates the greatest empathy. One additional advantage is that the team members can generate their own questions, and when the researcher is able to fit them into debriefing and other portions of the testing, it gets the team’s fingerprints on the results and helps get their buy-in.

Back in 1994, Jakob Nielsen edited a special issue of Behavior & Information Technology devoted to usability labs around the country that still has much to say about current lab design. Technologies have improved, but many of the patterns observed then still apply. I wrote an article about the lab I had designed for Ameritech (Lund, 1994a) in which I described a series of requirements for the lab and their priority for the kinds of testing we were doing then. The requirements included:

• Space to simulate the eventual usage environment (ideally easily reconfigured as needs evolve)

• Cameras to record the face and the user’s activity, a microphone to record the user’s remarks, and recording equipment with the ability to synch to time

• A way for a remote experimenter to observe the user’s activity (especially as being recorded) and to communicate with the user

• A staging area for users to help ease them into the test environment

• An observation area for observers (e.g., sponsors and team members)

• An environment for managing the lab and annotating the recordings that is easy to use for the researchers

Variations on that arrangement supported most of our needs (including both summative studies with researchers sitting in the observation room, and more formative studies where the researchers sit with the users and probe in the course of the interactions). When we built the lab, we used the traditional one-way mirrors between the observation and testing areas, but the available video technologies have advanced considerably since then and we have seen value in enabling remote observers to have active discussions during the study. These kinds of discussions typically need to be remote from the testing environment so the users are not disturbed. At Compaq I recall there was an area specifically designed for people to observe the observers.

Since most of our work involved workstations, for many studies we recorded directly from the monitor with a splitter, and used the cameras to focus on the face and the hands. Back in those days we also laid a track of SMPTE time code so we could synchronize the streams when we edited summary videos, and ran them through software that let us annotate the videos for later analysis. Today the video is immediately digitized, and observers can annotate (often collaboratively) as the video is being created. The coding allows the video to be more archival and to provide value beyond the individual study for which it is being recorded.

In that same double issue, Nielsen summarized the 13 labs that were described. The median floor space for a typical subject room was about 13 square meters (with a mean of about 19). Most labs had around 2 or 3 rooms. In general, there were 2 cameras per room (a few had 3), and in general half of the time they used a scan converter as well to record directly from a screen. Most (but not all) used a one-way mirror, and all had some staff whose responsibility it was to support the lab. The median ratio was 1 support person for 12 people using the lab. Another good source for usability lab examples is the Appendix in A Practical Guide to Usability Testing (Dumas & Redish, 1999).

Since then, usability environments have expanded in several directions. The concept of simulating the usage environment has caused more and more groups to build labs that duplicate a wider variety of environments. At Ameritech we built a teleconferencing room specifically for research, and eventually constructed a small home in the lab to study smart home control use. At US West Advanced Technologies we built a living room lab. I made a slight mistake there in that I had a new graduate select the furniture and decorations for the room, and it ended up looking suspiciously like someone’s fantasy bachelor pad. Since then I have seen IT environments where people are studying how administrators rack and manage equipment, and I have visited the headquarters of a drugstore chain where they had a simulation of an entire pharmacy.

As user researchers adapt more methods from market research, as participatory design methods are used, as information architects continue to use techniques such as affinity diagramming, and even as teams collaboratively sketch solutions to design problems, larger spaces make sense and a method of recording what is taking place can be useful. When a UX effort grows beyond a group, a larger space optimized for studying group activities can sometimes be justified. A large space, whether in a lab or in a hallway, is often a powerful tool for data analysis. Qualitative data can be placed in it, organized into meaningful units, and turned into a variety of models of users, their experiences, and their behaviors.

One of the finer examples of a lab I have seen recently is the lab seen in Figure 4.1 (designed for the Microsoft Servers team). The lab is completely digital and leverages the latest in data logging infrastructure created by the UX Central team in collaboration with the Visual Studio team. It has ample space for exploring information worker, administrative, and group activities (since a large amount of real-world IT work is social in nature). It is easily reconfigurable. The design elements of the lab have been chosen to make the users comfortable and create quality video.

|

| Figure 4.1 Usability lab. Published with permission from Microsoft, photograph courtesy of Paul Elrif and Tyron Chookolingo. |

Design Studio

When I joined Sapient, they had already started the process of creating identity among the user experience community and then quickly incorporating new employees into it. Some referred to it as “drinking the Kool-Aid,” but it was rare to find someone who regretted it. Many of the colleagues I have continued to stay in the most contact with over the years came through Sapient. Part of that identity-building process was to go through a multi-day introductory workshop.

At one point during that introductory workshop there was a tour and field work at one of the Sapient design studios in Chicago. The studio had been one of the E-Lab locations before it was acquired by Sapient. I remember that we were all excited about the new job. Sapient had an incredible reputation for user experience during those pre-Internet bubble bursting days, and it was truly exciting to be a part of the latest “class” of new recruits. We walked for blocks and blocks through the Chicago late Fall chill. I remember talking with someone about their interest in marathoning, and briefly wondering whether that might be something to tackle someday. We arrived at a classic Chicago brownstone. This was the kind of building in Chicago with old wood with dark varnish and brass fixtures, with lathe and plaster in the old parts; the kind that smells a hundred years old, but in a good way. It was downtown and there was plenty of urban energy. We went upstairs and then came into this amazing space. It seemed mostly open, except there were exposed brick walls. On the walls were collages of pictures and notes from research that was underway with stylized stickies to help organize the information. There were design posters on the walls. There were strange toys, bicycles, inflatables, and other things hanging from ceilings. The whole place was filled with the creative clutter that decorates the minds of many user experience people, and which supports the kind of serendipitous connections that generate new ideas and insights. There was a definite excitement in the place as people moved throughout, and there was talking and laughter everywhere.

When we built out the Sapient Denver office it was a blank slate. As with the former E-Lab location in Chicago, the Denver office had an urban feel as it was located in the LoDo (Lower Downtown) district. The area was very trendy with lots of little boutiques, great restaurants and clubs, and warehouses converted into condos. In our building a floor had been knocked out in the building we were in, and large open spaces were created. The exterior walls were large windows looking out on the city and the Rockies. The remaining walls were virtually floor-to-ceiling whiteboards generally covered with designs, code, research, project status plans, and other artifacts of the process. Off the rooms were smaller breakout rooms where the walls were all whiteboards in which working groups could go to collaborate on designs. In the open spaces we sat at moveable tables that could be reconfigured as needed, and everyone working on a project was physically located together. The breakout rooms held couches, foosball tables, video games, and so on, to break up the long nights. Off one end of the building was a huge outdoor patio area wired with Ethernet so people could get quiet time and work in the fresh air, and where there were frequent BBQs for people to bond. There was an impressive lobby where the Sapient brand and successes were clearly displayed, but once the clients moved past the lobby they were immersed in our process and activity.

Tom Kelley (2001) argued that innovation flourishes in greenhouses. He argued that a greenhouse is a workplace designed to foster the growth of good ideas, a place designed to support collaboration. IDEO considered their spaces a primary asset, as did Sapient. Visiting the offices of leading design vendors in the Seattle area and some of the most innovative teams with whom I work, I see a similar design studio vision repeated again and again. Kelly argued that, in general, when putting the space together the fewer the rules the better. He does flesh out several principles in the course of his book, noting that you

Start by building neighborhoods and thinking in terms of projects. Make building blocks to create playful, flexible foundations for your workers. Throughout the process, remember the spirit of prototyping. Space should evolve with teams and projects in much the same way as do your plans for an innovative new product. Encourage hot teams to find or create a team icon. Finally, don’t forget that your spaces should tell stories about your work and your company.

Furthermore, your spaces help project the identity for the team.

Within my current role I have been moving in this direction myself. Space is limited in our area so when we were a smaller team we arranged with the administrative assistant owning the space to let us have a large lounge area on one floor and we turned that into a design studio. When all the teams in the organization were being moved around, we started looking for unused spaces. We found a lab that had originally been used by the games group and arranged to get access to it as a design studio in exchange for the cost of painting and cleanup. The full space included a small usability lab, some rooms that had previously been usability labs that we are going to turn into breakout and project rooms, a very large conference room that we treated as the center of the team space, and a room with cubicles that had been used for mass games testing that we converted to house contractors and vendors. The next step was to arrange for my team to have our offices consolidated around the space. We pushed the artifacts of our design process and examples of our best work out into the halls around the space.

Ambient Spaces

Space shapes our attitudes, how we interact, and in many ways how we think. Every place where I have seen a vital, influential user experience team I have seen a space that reflects their creativity. At Sapient part of the signal of what we wanted to be about was floor-to-ceiling whiteboards and whiteboards that were covered with sketches, diagrams, and plans. The walls were covered with posters, clippings, and printouts of data and screen shots. People were standing next to them gesturing and drawing in groups. The whiteboards were a living environment and yet they also persisted over time to support asynchronous collaboration and the reinstating of previous trains of thoughts.

Around many companies you know you are walking into a user experience space because you start to see designs on the walls. You see data and figures laid out and experience models taking shape before your eyes. At times there are more organized signals of the kind of space you are in. There may be more ordered comparisons of design screen shots, or personas laid out next to each other, or photographs capturing images that stimulate the emotions that are being targeted, or posters of style guides. There may be framed versions of past design milestones and successes. There may be spontaneous art projects. There may be representations of the design language being used by the team.

Turn the walls of the halls into design spaces (Figure 4.2). It encourages each member of the design team to look at what others are doing and engage with it. It brings the perfectionists out of their shells a little, and forces them to share incomplete design and open themselves to others feeding into their design process. It enables those engineers who may work sitting behind their screens to really see what is behind the evolving design, and that while it is messier than they may be used to, it also is informed by principled ways of thinking and talking. Furthermore, pushing the design out into the public spaces invites that public into the design process, because when walking through the halls they cannot help but engage at some level (and may actually have to push their way through the design process in action).

|

| Figure 4.2 Collaborative MS IT hall art. |

Tools

Engineers have impressive tools. Most of the organizations I have been in have hardware labs on raised floors with racks and racks of equipment and blinking lights, and much of the budget discussion each year is around the servers in these rooms, the automated test tools, and other things that you can see. The only things missing are those tape drives from the old science fiction movies and there are not nearly enough blinking lights. I have always enjoyed building and managing UX labs. They are a visible example of what we do. But I admit I’ve also been a little envious of the toys the engineers always seem to have.

UX also needs tools. Designers need really zippy machines with the horsepower to drive the various programs they are using. They need big (or multiple) screens to work on. They need laptops that are similarly powerful and often with larger than normal screens so they can take the work on the road when they go sit with developers and work. Conference rooms today typically have projection systems for sharing designs, but if there is extra budget you might want to arrange to have access to an easily portable projector for their laptops in case it is needed. Admittedly, given the ubiquity of projectors this is a pretty low priority. Make sure the computers have the usual design tools (Photoshop, Illustrator, etc.), and remember they can be quite pricey. Even upgrades are often expensive and you will want to plan to keep the software up to date.

There should be some kind of collaboration environment for storing and sharing designs. At Microsoft that is called a SharePoint site. We usually float between sites we share with the teams that we are collaborating with and a team site that makes it easy for everyone to see what everyone else is doing.

At one point our CIO worked in the auto industry. The vision he outlined for how design worked there is compelling and is something we are working toward. It begins with sketching, paper vision prototyping, and other activities to get ideas out on the table. These prototyping tools may include PowerPoint or Visio, paper, or even whiteboards (or whiteboards that can be easily digitized). Alternative designs are captured and saved on the walls of team rooms, hallways, and in other areas where they can stimulate creative solutions to the needs represented in the user scenarios.

PowerPoint, Visio, and even Excel can be used for simple wire framing. We have created libraries of templates and common controls to simplify this early envisioning. The goal is to move these sketches into a digital form and start to piece together low-fidelity prototypes for how the interaction is going to work and that embody the information architecture. There are a variety of tools on the market for facilitating this rapid prototyping stage. Balsamiq is an example of one of these. It is light, easy to use, and inexpensive. It gives a feel of the basic interaction. SketchFlow in Microsoft’s Expression suite is a richer tool, but with that richness comes a little more complexity. Sketches can be imported in a variety of forms and you can rapidly build an interactive prototype. The prototype can be “published” for users to comment on as they interact with it. The design can be fleshed out and feeds common development tools, and documentation can be automatically generated about the design.

This early prototyping serves to bring everyone together around a common language for the design. These prototypes ideally are suitable for user research. What you want is to build out the fidelity of the screens as they become complete and to attach simulated data to make sure the interactions work right. In the next stage these designs need to feed the development tools, so they need to either output code in the appropriate format that can be input into the tools, or the tools need to be part of an integrated environment. While development is going on, the ability to have both a designer’s view and a developer’s view is useful. Each works in their own environment and you want them to see what the other is seeing. You want to be able to output through this process to a form that can be used for testing. Ideally you can track generations of the design and comments that lead to changes in the design (e.g., from research).

Researchers need a user testing environment (described earlier), and they need software to analyze the data. Labs now are usually entirely digital and the various sources of information all feed a single database. As the data are collected they are annotated so they can become intellectual capital and inform decisions far beyond the specific studies for which they were originally collected. Excellent tools are on the market to support usability labs, or you may choose to develop your own in order to achieve a full integration of the wide variety of sources of information you are collecting locally and remotely. Whether buying or building the software, it will need to be planned for in your budget. Video editing software makes it easier to turn the data into clips that can be attached to reports and circulated among stakeholders. Researchers may need a questionnaire tool that has to be budgeted for, and tools for affinity diagramming and analyzing field data. Some labs (especially those focused on Web design) have an eye tracking system. We document studies in research reports, and have a database where those reports can be stored (so they can be used to answer future questions, much like the data). Laptops make sense for researchers, even if they also have a workstation. Laptops are used in the field and for presenting work to teams. A variety of mobile labs are typical for many teams (Lund, 1994a) and are easy to assemble, especially given affordable video cameras and Internet streaming for sharing the studies as they are underway.

In addition to the usual research tools your team with also need access to users for testing. For some projects you may need to work with field people to get access to customers and other users. You may need to create your own database, continually populate it with the names of users, and track which studies those users have been through. The creation and administration of the database and the costs of recruiting (e.g., through recruiters and advertising) need to be in the budget. At some companies a centralized user experience organization does the recruiting through advertisements, through the corporate Web site, and through other channels. In addition to the costs of acquiring people to test, you will need to provide for some form of gratuity to compensate people for participation. At Ameritech we paid approximately $50/hour, and at software companies you might pay with software. When we use employees we often repay them either with small gifts or with gift cards. Note that when payment exceeds certain levels you may need to report it as income for tax purposes, especially when paying for research outside the United States. Another issue that has arisen is around policies governing “gifts” of products and whether a gratuity is payment or a gift. You may need to work with your legal department to shape a policy that makes sense. For international research considerations a good reference is Schumacher (2009).

An additional consideration at most companies will be to work with legal to ensure forms are created to cover non-disclosure of corporate secrets (e.g., the designs of the product prototypes you may be testing). You will need to create a document that the legal department reviews to protect the privacy of the people you test, yet that allows you to use video and other data you collect with the teams to inform design. You should define a policy around archiving the data and how long it will be held, and when and how it will be destroyed. Most companies have limitations on how long they keep various kinds of documents in their files.

While I can honestly say I have not seen it being done as much as I would like, I believe that it would be good for your user experience team or community to define a set of ethical policies that inform how you treat the people who participate in your research. That belief probably goes back to when I ran the human subject pool at Northwestern as a graduate student, but it does seem the right thing to do. First, determine the limits of deception. In general there does not seem to be the same legal requirement for these kinds of policies as the non-disclosure and the release documents, so it probably could be defined simply as another step in building the identity of your team (since it will be tied to your team’s values). However, if you are testing kids (e.g., a gaming application), that requires a careful collaboration with the legal department to create the right set of documentation and policies. There are a variety of issues about compensation, the nature of the content the kids will see, who will be alone with the kids and when, how distress is handled, and so on that will need to be anticipated.

Budgeting

The blood that keeps your team alive is your budget. If your team is positioned lower in the organizational structure, your budget will probably be handled by a higher level manager and it may be hard to actually see it broken out by category. Not having your own budget reduces some of your flexibility, especially if you might be able to move money between line items as long as your overall budget is on track. The higher up you are in the organization and the larger your team, the more likely you will be able to manage your own budget. Whether you control your budget directly or not, you would like to be in the position to request and receive a budget that will help you make the bigger leaps toward your vision — the budget that you can invest in key strategic activities. When I have been in a team devoted to a single product, my requests were treated (and evaluated) the same way as business cases for features within the product. The budget also needs to provide for costs that are unique to user experience teams such as recruiting users and funding research.

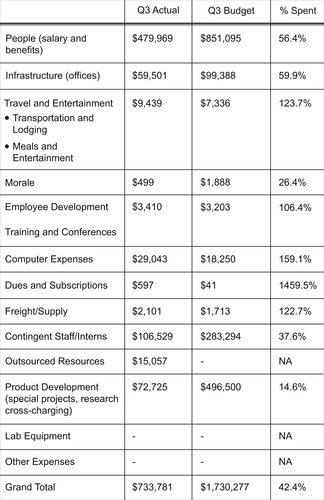

Figure 4.3 shows a portion of one of my budgets. It is a snapshot of one quarter, and the full budget report would typically show the budget for the year, the year-to-date spend and budget, and the most recent month. In some teams I received a monthly update and in others the budget was worked through quarter by quarter. Another task in some companies has been to not only project a month-by-month expected spend, but I have also been asked to periodically update the projection. This can be quite a challenge since for most of my teams I have really only had visibility into the activities over the next quarter. Projects change so quickly that the design and research activities need to change with them and those changes clearly impact the budget. Since finance people generally do not care about details like actual confidence in the budget, the projections often have to be based on past trends and then adjusting based on what I expect demand and activity will be like, rather than basing them on hard project plans. More recently these budget adjustments have become critical, because at the top of companies they have started the practice of looking at underspent budgets (based on projections) and then pulling the unspent dollars back to reinvest in the corporate priorities. This is an attempt to avoid the practice of teams spending anything in the budget that has not been spent before the quarter or the end of the year is over. The downside is that efforts to save money today to buy something bigger tomorrow can be hard. Thinking through the budget, even without the data you would like to have to do it, is therefore often critical for the operation of your team and the growth of your user experience effort.

|

| Figure 4.3 Example budget. |

In the budget in Figure 4.3 the biggest line item is clearly the salary, bonuses, and other compensation for the full-time staff. The next biggest is the budget for the special, strategic projects that were added to the budget. This item also includes the cost of doing our research. Some of those projects involved hiring vendors and others involved major research investments. The third largest portion is the contractors (who are distinguished from vendors) and interns who give me flexibility in my staffing. Other budget items included the infrastructure (e.g., cost of office space) that comes with having full-time staff. Travel and entertainment, employee development and conferences, and computer expenses are about the tools used to get UX jobs done and to grow people. The morale budget was specifically for team-building activities. Other items can easily vary from organization to organization and company to company, but these major ones are typical across companies.

Other Opportunities

You do not always have the budget for what you want to do and the rules for getting it may not always be obvious. One of the virtues of a startup is that while things are lean everyone does whatever is needed to move the business forward, and while you are all in it together you are ready to improvise. When I was going through the welcome-to-Sapient training one of the things that was impressed upon each of us was people are not always going to tell you how to get what you need. You need to go find it. If you are on a consulting gig go find the supply room, talk to the administrative assistant, work out of Starbucks, do whatever you need to do. One of the things that makes or breaks people in large corporations is whether they feel constrained and limited by all the rules and structures, or whether they see the size and then see the cracks between the processes and rules as opportunities that they can leverage when trying to get things done.

There are times when you need to push the limits and take reasonable risks. We have talked about putting things on walls to create an ambient design space. If you actually track down the building manager to ask permission the answer is very likely going to be no. If you just put something up, what is the worst that can happen? Someone will take it down and ask you not to do it again. If they do, then that lets you start a conversation about how that kind of space is important and you brainstorm together about how to accomplish your goal. Can you put up corkboard? Can you get a team room? Are there spaces where it might be okay? In many of these situations the phrase “don’t ask permission, ask forgiveness” makes a lot of sense.

One of the things I start looking for in a new organization is who manages the space and whether there is a separate budget for decorating that space. Often the space budget sits somewhere outside of daily operations and is only used for major moves, repairs, and so forth. In one team, we tracked down the administrative assistant who owned it and uncovered a couple of small conference rooms that people were not using for offices. We found budget for the space, and convinced the administrative assistant to let us turn the two small rooms into a design studio. If we ever moved, they would still have a big conference room. We then used the budget to buy a large screen, a projection system, and several computers along with couches, chairs, and tables. Several members of my team went to the hardware store and bought those really big whiteboard sheets and mounted them to the walls (and having extra, went around and redecorated some of our offices). The whiteboards let us sketch and explore design ideas. The studio became the center where we held our design critiques, and where we could post designs and leave them in place for extended periods.

One of my team members discovered in the process of reorganization that there was an office that had not been assigned to anyone. It was an inside office, so it was not under heavy contention. He talked nicely to the administrative assistant and argued he could really use a team room dedicated to his project for a few months and she said okay. He then went to the hardware store, bought bright green paint, and painted the office with it. (Immediately that reduced the likelihood that someone would want to take it over.) He found a furniture budget that had not been used in years and bought a bunch of Aeron chairs for the room and a great table. He had a special sign made with etched clear plastic that said “The Green Room.” That became a part of what we were as a team and a focal point for the sub-team that he was leading.

Another example came at the end of the first year in my current organization. We were looking for a space that could be used for a team room for design critiques and participatory exercises and as a lab space. I found the administrative assistant who handled the space and we had a great talk. There was a storage room that she said we could have that was not being used for anything. Another space that I believe Pam came up with was a lobby area on the third floor of our building. A few chairs were sitting there if I recall, but it was not being used for anything else and it was just outside my office at the time.

For the storage space the first thing Pam did was to put a lock on the door to protect the space, and later we set up a reservation system to manage it. Initially we were thinking about turning it into a discount usability lab, since my researchers had to travel a half an hour or so to the main campus in order to do research. I wanted something that would enable more of our team to observe the tests. The team who manages the labs for the user experience community arranged for the building people to come and join them in evaluating the space. It turns out that when you are building labs like this you have to worry about where the air is flowing, fire danger, where the wires are piped, and so on. We learned it could cost a lot to turn it into a standard usability lab. So that ruled out our initial approach.

But then one of those opportunities emerged that you need to seize when you can. We were getting toward the end of the year and my boss had a lot of surplus money in his budget. The one constraint was that it had to be spent, and whatever it was spent on, had to happen within a month. Pam took this project on and with frequent trips to Ikea, to the hardware store, and many calls to a few vendors, the two spaces were turned into effective collaboration spaces. Both had projection interactive whiteboards where you could sketch and record the digitized images on your computer. We could store some of the field research equipment in the storage room, but both provided spaces where we could mount designs and research, and let them stay up over extended periods of time.

We have also been successful in working with some of the teams we support and in keeping our eyes and ears open to see when they have a little extra budget. We have been able to get them to fund anything from software upgrades to travel outside the standard travel budget, to vendors for special projects, and most recently, replacement laptops for the team. As a manager, one of things you should make sure you have is a list of things you would like to have if money becomes available. You can use such a list if you do come up against budget deadlines and when someone asks “Is there anything we need that we should spend this money on?”

The other phenomenon I have noticed is that sometimes being more outrageous in the dream is better than being more modest. You might not be able to get a few thousand dollars to upgrade your team’s equipment, but if you ask for a million to rethink the entire vision of your space and turn it into a design studio you might be able to find it. Again, the money may come from a different budget and something as bold as an entire design studio may serve the needs of an executive who is looking for a way to make her own statement to senior executives about the leadership she is providing.

Hints from Experienced Managers

Hints from Experienced Managers

Boldly delegate responsibility to your team. It helps them grow and allows you to scale. It also gives them ownership and ensures that you are not the single point of failure.

Andy Cargile, Director of User Experience, Microsoft Hardware, Seattle, WA

Do the work too. Don’t just tell people to do it. Your staff has to know you can and will pitch in when needed AND that you can lead by example.

Robert M. Schumacher, PhD, Managing Director, User Centric, Inc., Oakbrook Terrace, IL

Robert M. Schumacher, PhD

Managing Director User Centric, Inc., Oakbrook Terrace, IL

The good news about budgeting for user experience researchers is that, for the most part, this is not a capital-intensive business. Nevertheless, it is important to make a priority to ensure our staff have the tools necessary to do their jobs with excellence. In our experience, the capital expenses fall into one of three general categories: lab space, lab equipment, and technology for the researchers/consultants.

Rent takes the biggest chunk of the budget, and cost will, of course, vary depending on where you are. One of User Centric’s offices is on Michigan Avenue in Chicago, which is an expensive location. But it’s where our clients expect us to be, and it’s where participants can find us, so we accept the expense as necessary for running our business. No company wants to overspend on space, but it’s crucial that your offices and labs have a high-quality feel and project an appealing, professional image.

The next highest equipment cost comes with setting up labs. There are two areas to consider: technology to do or deliver the research, and technology that is being researched. To do the research, you need to be forward thinking about the kinds of services you plan to provide, and invest in a quality environment where researchers can work to their highest capability. In this day, it means having large-screen monitors, HD cameras, and lots of gizmos and gadgets that can do important technology tricks. We research a lot of cool tech products, so that we can make sure our labs have high-quality audio, video, software, and other technical capabilities. Capabilities like recording software or streaming require budgeting for the infrastructure and software, and maybe the technical resources to run it if the researchers are not able. As for technology that is being researched, if you work with particular devices (e.g., TV services or kiosks or mobile devices) you must budget for continually upgrading equipment used in tests, as well as for the service necessary to run these. For example, if you work with digital TV, budget for cable systems and possibly HDTV service in addition to the televisions themselves.

The capital expenses required for setting up a lab are significant at the outset. However, we’ve found that with each lab space we’ve built, the capital requirements to do what we’ve done in the past go down. It’s very important to keep labs state-of-the-art. To this end, you must dedicate part of your annual capital budget to improving (not just maintaining) technology resources to keep up with new lab technology used to test and new technology used in testing.

Equipping individual consultants is relatively modest, but varies depending on the individual. In general, the majority of researchers fare well with a reasonably powered laptop, a cell phone, and typical office productivity software. For designers, the hardware and software demands increase considerably. Prototyping and visual design tools tend to be quite pricey. Then there’s software that is required to run the business that is expensed month to month (e.g., time and expense reporting systems, screen sharing tools, VOIP systems); these tools can easily add an amount on a monthly basis that will impact the budget over the year.

Other expenses may come into play if consultants will be doing international testing, or work involving specialized equipment like eye trackers or driving simulators, but these are more exceptions than the rule. The useful life of most consultants’ hardware is 12–24 months, so there should be allowance in the budget for updating researchers’ capital resources.

While expenses for a user research team may be less than some other businesses, it’s still important to be aware of where you can and cannot cut corners. Since what we as user researchers sell is knowledge and expertise, it’s important to budget for regularly maintaining up-to-date facilities and equipment that will maximize your capabilities, as well as convey a sense of competence to your clients.

There is one other thing, our clients are watching. I had a client say to me the other day “I like to see what you usability guys are using.” No pressure.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.