PART III

12 LESSONS IN LEADERSHIP

LEADERSHIP LESSON #1: GOOD VALUES ATTRACT GOOD PEOPLE

Treat all people with dignity and respect.

What I Learned

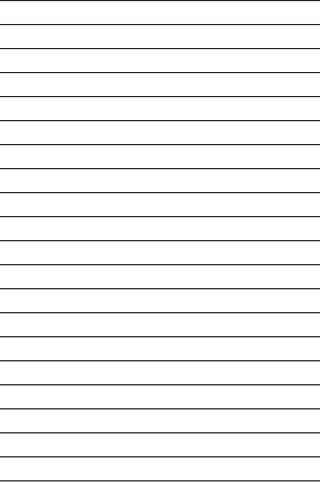

BY KAREEM ABDUL-JABBAR

UCLA VARSITY, 1967–69;

THREE NCAA NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS

John Wooden built his basketball program a certain way—athletically, ethically, morally—because he believed it would attract a certain type of person, the kind of individual he wanted on the team. He was right.

I chose UCLA and Coach Wooden in large part because of those values. It was like that movie, Field of Dreams: “Build it and they will come.” He built it. We came.

What It Means

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar is “the most valuable player to a team in the history of the college game,” in the judgment of Coach John Wooden. Abdul-Jabbar went on to become the NBA’s all-time scoring leader.

As a high school player at New York’s Power Memorial Academy, Abdul-Jabbar was the most sought-after student-athlete in America. The coaching community was in general agreement: the school he chose would soon be the national champion.

Why did this extremely talented young man, a native New Yorker who wanted to stay close to home, choose to attend a university that was on the other side of the country—UCLA? The simple answer? Values.

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar had become aware of the values and standards of UCLA, including full integration and high academic standards. He had also become aware of the character of its coach, John Wooden. Former players had repeatedly told the young high school star, “Coach Wooden is color blind when it comes to race.”

UCLA and its varsity basketball coach were the beneficiaries of the great athletic and academic talent of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar because he was drawn to their shared values and standards. He was not the only individual to choose UCLA over other opportunities because of its outstanding reputation.

Character— |

Values, standards, and character mattered to Abdul-Jabbar and his parents, Cora and Lewis Sr. They also mattered to John Wooden. And in large part he learned them from his dad, Joshua Hugh Wooden, and his three influential mentors, Earl Warriner, Glenn Curtis, and Ward “Piggy” Lambert.

You and your organization’s good values, standards, and productive attitudes will attract individuals who have the same.

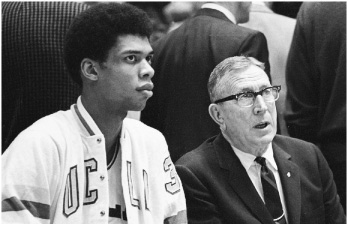

Aristotle said, “We are what we repeatedly do.” He was referring to character—the habits of our daily behavior that reveal who and what we are. I wanted to create good habits in those under my leadership. Standards, values, and attitudes were important to me. I wanted them to matter to those I taught.

Here’s a good definition of character: respect for yourself, respect for others, respect for the rules. For those I coached, I believed that character started with little things like picking up after yourself (rather than expecting the team manager to clean up your mess) and extends to big things like honesty, compassion, and the 15 personal qualities I placed in the Pyramid of Success. I sought individuals who had character rather than individuals who were just characters.

Leadership is about more than making people do what you say. A prison guard can do that. A good leader creates belief—in the leader, in the organization, in its mission. This is difficult to do where a vacuum of values exists, where the only thing that matters is a bottom line, winning the race. All kinds of bad things can happen when the only thing that matters is “winning.” Just read the newspapers today and you’ll find all the evidence you need that this is true.

The kind of people I wanted to have running the race with me were those with whom I shared a code of behavior—values and standards. This didn’t always happen—after all, people are human—but one of the primary ways to ensure that this occurs is to make your values visible, to let the outside world know what you stand for and who you are.

In doing so, you will attract those who share your principles and standards.

Your behavior as leader—what you do—creates the environment in which the team functions.

LEADERSHIP LESSON #2: USE THE MOST POWERFUL FOUR-LETTER WORD

What I Learned

During World War II I’d been shot down in a B-24 bombing raid on Italian oil fields and almost got killed. I had a fear of flying after that—would not get on a plane.

When I got out of the military, I went to Indiana State, where John Wooden was head coach. He had been my coach at South Bend Central High School. One week we were scheduled to play a game in New York, which meant an airplane trip to the East Coast. There was no way I intended to get on that plane. Absolutely no way.

When Coach Wooden found out about my problem and why I wouldn’t fly, he said the solution was simple: “Nobody on this team gets left behind.” So he rounded up cars, and we drove to New York.

If you played for John Wooden, you were part of his family. We felt like we were in a family. And we were. In fact, I still feel like I’m part of his family.

Be more concerned with what you can do

for others than what others can do for you.

You’ll be surprised at the result.

What It Means

John Wooden did not consider those he coached as plug-in parts, “jocks” whose value was in direct proportion to the number of points they could score. In a very real sense, he felt each student-athlete was a member of his extended family. And he reminds us, “Love is present in a good family.” You must demonstrate it in appropriate ways with support and concern within a disciplined environment.

In the early days of his teaching, Coach Wooden started each season by trying to express his intention to be impartial with the following statement: “I will like you all the same.” And then he would add, “And, I will treat you all the same.” Of course, this turned out to be false.

The smallest |

There were some players on the squad that Coach Wooden could hardly stand, and it troubled him because he felt strongly that a leader should be “friends” with those under his supervision. Furthermore, he recognized that he did not treat a hardworking player the same as one who was less so. Treating everyone the same, he soon realized, was unfair.

During this period he read a statement by Amos Alonzo Stagg, Chicago’s legendary football coach, that helped him reformulate his perspective on the relationship between a leader and the team. Coach Stagg said, “I loved all my players the same; I just didn’t like them all the same.”

By the time Coach Wooden arrived at UCLA, his message to the players at the beginning of each season was as follows: “I will not like you all the same, but I will love you all the same. Furthermore, I will try very hard not to let my feelings interfere with my judgment of your performance. You receive the treatment you earn and deserve.”

Nobody cares how much you know until they know how much you care. The individuals on our UCLA teams became true members of my extended family.

I once bailed a player out of jail for a driving violation even though it went against conference rules. These and other acts of kindness and concern were small gestures, but a direct result of the feelings—the love—I had for those under my supervision. It’s vital to let those you lead know you care. First, of course, you must have that care in your heart for those you lead.

And while I could have great love in my heart for those under my supervision, I would not tolerate behavior from anyone that was detrimental, or potentially detrimental, to the welfare of our group.

For me, it is possible to have the greatest care and concern for someone and bench, suspend, or even remove him from the team.

COACH WOODEN’S X’S AND O’S: |

USE THE MOST POWERFUL FOUR-LETTER WORD |

• The people in your organization are your extended family. |

• Coach Stagg’s advice is apt: “Love” is more important than “like.” |

• Treating everyone “the same” is not fair. Each member of your team should get what they earn and deserve. |

• Seek opportunities to show you care. The smallest gestures often make the biggest difference. |

• Love does not mean you tolerate bad behavior. |

LEADERSHIP LESSON #3: CALL YOURSELF A TEACHER

What I Learned

BY DENNY CRUM

UCLA VARSITY, 1958–59; ASSISTANT coach, 1969–71;

TWO NCAA NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS;

HEAD COACH, UNIVERSITY OF LOUISVILLE

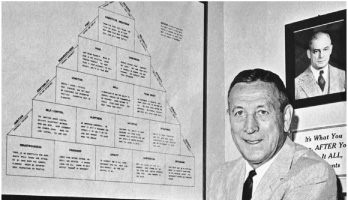

Coach Wooden’s philosophy was to teach what was necessary to make UCLA a better team—the best we could be. Teach it; practice it. The details and all of the fundamentals were his main concern. Thus, he never talked about the winning or the losing. He wouldn’t come in before a game and say, “This team is tied with us in the conference, so we’ve got to step it up tonight. Let’s win this one.”

He just wasn’t concerned about the opponents and what they might be up to—didn’t even scout most of them. He felt that if he taught us what was necessary, we’d do fine. He was really a good teacher.

Each member of your team has the

potential for personal greatness;

a leader’s job is to teach them how to do it.

What It Means

BY STEVE JAMISON

The outside world knows your profession—what you do—by the title on your business card: sales manager, CEO, production supervisor, or something else. However, don’t be misled by what it says on your card.

In the eyes of many observers, John Wooden’s business card should say “Coach,” but this is not what he would choose. From the earliest years he has called himself a teacher.

The most effective leaders are good teachers. What does an effective leader teach? Regardless of context, it is the same, namely, how to perform at your highest level in ways that serve the welfare of the organization.

If there is a single reason the UCLA Bruins enjoyed success in basketball while John Wooden was head coach, it was because he learned how to be a good teacher, not only of the X’s and O’s, but of the more elusive qualities such as Team Spirit, Cooperation, Initiative, and the other components of his Pyramid of Success.

As a young and inexperienced coach, John Wooden was impatient. When things weren’t done correctly “right now,” he pushed harder and talked louder.

Increasingly he began using the Four Laws of Learning: Explanation, Demonstration, Imitation—correction when necessary—and Repetition. These are the same as the Four Laws of Teaching, and both require great patience. This is why he included Patience in the pyramid.

An effective teacher must also have a good hat rack, one with plenty of hooks for all the different “hats” you wear: teacher, of course, but also disciplinarian, counselor, role model, psychologist, motivator, timekeeper, quality control expert, talent judge, referee, organizer, and more.

An effective leader is very good at listening.

It’s difficult to listen when you are talking.

A good teacher is a good student, a lifelong learner. No two people are the same. Each individual under your leadership is unique. There is no formula that applies to all when it comes to teaching and leading. All won’t follow; some need a push. Some you drive, others you lead. Recognizing the difference requires a knowledge of human nature. That’s where being a good student helps you in your leadership.

I taught by offering information in small bite-size pieces rather than large chunks that couldn’t be assimilated easily. I tried to set the example I wanted those I coached to follow. The greatest teaching tool is your own example. I studied human nature. I kept learning. I kept teaching.

And when I asked the question 100 times, I asked it again: “How can I help our team improve?”

COACH WOODEN’S X’S AND O’S: |

CALL YOURSELF A TEACHER |

• The greatest teaching tool is your own example. Your deeds count more than your words. |

• Be patient. People progress at different speeds. |

• A good teacher wears many hats. Make sure they all fit your head. |

• A good demonstration is more effective than a great description. |

• A great leader is a teacher who is a lifelong student. |

LEADERSHIP LESSON #4: EMOTION IS YOUR ENEMY

What I Learned

BY FRED SLAUGHTER

UCLA VARSITY, 1962–64;

ONE NCAA NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIP

There were four or five games in my career when we started out way behind like, 18–2—just getting killed. I’d look over at Coach Wooden, and there he’d sit on the bench with his program rolled up in his hand—totally unaffected, almost like we were ahead. And I’d think to myself, “Hey, if he’s not worried, why should I be worried?”

Instead of panic, I settled down, and so did the team. We won each of those games except one.

John Wooden was cool when it counted; his confidence and strength and attitude became our confidence, strength, and attitude. In three years on the UCLA varsity, I never once saw him get rattled, and we had some nerve-rattling games, including a last-second loss in the Final Four to Cincinnati.

Coach was cool, and he taught us to be the same. Especially under pressure.

What It Means

BY STEVE JAMISON

Extreme intensity—controlled and correctly directed—is an essential ingredient for unswerving—consistent—productivity and competitiveness. Emotionalism—temperamental flareups and drop-offs—makes consistent high performance impossible.

A leader controlled by emotions will produce a team whose trademark is the roller coaster—ups and downs in performance; unpredictability in effort and concentration; one day good, the next day bad. John Wooden has deep disdain for the “roller-coaster” pattern in both effort and performance.

Thus, he never gave rah-rah speeches or contrived pep talks. For every artificial emotional peak attained, you and your team will be subjected to a valley, a letdown.

If you let your |

Coach Wooden demanded intense and steady effort with the goal of producing consistent ongoing learning and improvement. This, in his view, was preferable to getting individuals heated up for some arbitrary peak in performance, which would be followed inevitably by a drop-off in effort and execution.

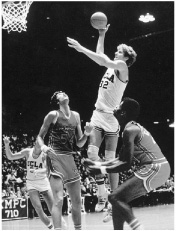

In all UCLA basketball practices and games, he demanded intensity that did not boil over into emotionalism and loss of self-control. Former UCLA center Bill Walton describes that intensity during a practice as equal to what he experienced in actual games—including games to decide a championship.

Ideally John Wooden wanted the team to improve during each practice and game—every day, each week—throughout the season until they were at their finest on the final day of the year.

Steady, constant, reliable, and complete effort that leads to improvement that was manifested in performance at an increasingly high standard was his goal. It is almost impossible to overstate the primacy of this goal in his leadership philosophy and methodology. To achieve it, Coach Wooden required emotional control both in himself and in those under his leadership. It took him many years before he mastered it, and even then not completely. He prized intensity and viewed emotionalism as a weakness.

Intensity makes |

S ome observers described me as being detached, almost stoic, on the bench during games. This could hardly be further from the truth, but it was a compliment nevertheless.

Emotionalism—ups and downs in moods, temperamental outbursts—is almost always counterproductive, at times ruinous.

I came to understand that if my own behavior was filled with outbursts, peaks and valleys of emotion and moods, I was sanctioning it for others. As the leader, my own behavior set the bounds of acceptability.

Subsequently, I became much more vigilant in controlling my feelings and behavior. My message to those I led was simple: “If you let your emotions take control, you have lost control. You are vulnerable.” For those under my supervision to learn the lesson, however, I had to control my own behavior and emotions.

Subsequently, I never second-guessed myself for decisions and actions that didn’t work out if they were made using my best judgment and all available information. It may have been a mistake, but it was not an error.

It becomes an error, however, when the choice was made because emotions spilled over and diminished the quality of my decision making. Early in my career the errors were common; there were fewer as my emotional control became more disciplined.

A leader defined by intensity is a stronger leader. A leader ruled by emotions is weak, the team vulnerable.

LEADERSHIP LESSON #5: IT TAKES 10 HANDS TO SCORE A BASKET

What I Learned

BY RAY REGAN

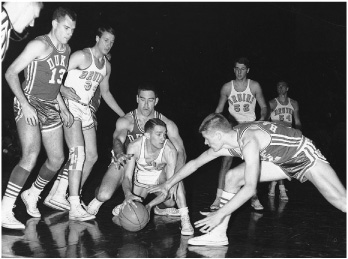

SOUTH BEND CENTRAL HIGH SCHOOL VARSITY, 1938–39

I remember we used to have a showboat on our team, a player who was always yelling for the ball, and then once he got it would keep it until he took a shot. Then he’d start yelling for the ball again. He was having trouble with Coach Wooden’s concept of teamwork and sharing.

One day Coach decided to teach this guy a lesson. He took us aside and said to pass the basketball to the showboat and then immediately run to the middle of the court—all four of his teammates—sit down, and let him face the other squad alone.

It was Coach’s way of showing that everybody helps everybody or nothing gets done. The showboat started passing the ball after that.

Be sure you acknowledge and give credit to

a teammate who hits you with a scoring pass

or for any fine play he may make.

What It Means

In basketball, a field goal is scored only after several hands have touched the ball. In business, the “ball” is knowledge, experience, ideas, and information. Whether on the court or off, that “ball” must be shared quickly and efficiently to achieve success.

A salesperson, or any other member of your organization who has the “ball,” must share it. A “me first” person puts the team second. That person is not a team player.

Getting those under your supervision to think “team first” starts when you teach every person in the organization that their role is important in some way to the welfare of the group.

All roles, every job, contribute in their own way to the success of the organization. Some individuals are more difficult to replace than others because of differences in ability, but every person you bring into your organization contributes—or should—to the overall success of the group.

Each must feel valued, from the secretary to the salesperson to the senior manager. When they understand that they are contributing members of the team and that their role has value, good things will occur.

Have one team, |

For this reason, Coach Wooden was the first in college basketball to insist on the “acknowledge your teammate” rule—namely, giving a nod or a wink to the player who gave an assist.

Coach Wooden wanted the player who scored a basket to understand that he was only as good as the team assisting him, that it takes 10 hands to score two points.

No matter how great your product, if one of your departments doesn’t produce, you won’t get the results you want. Everybody must do their job.

I told players that we, as a team, are like a powerful race car. Maybe a Bill Walton or Kareem Abdul-Jabbar is the big engine, but if one wheel is flat, we’re going no place. And if we have brand new tires but the lug nuts are missing, the wheels come off. What good is the powerful engine then, when the wheels come off? Every part, big or small, on that race car matters. Everything contributes to the running of the race. And, of course, a car needs a driver. I was the driver.

I don’t need scientific evidence to know that Rudyard Kipling was correct: “For the strength of the pack is the wolf; and the strength of the wolf is the pack.”

That describes the relationship between the individual and the organization—the player and the team.

Acquire peace of mind |

LEADERSHIP LESSON #6: LITTLE THINGS MAKE BIG THINGS HAPPEN

What I Learned

There was logic to every move. Details of socks, shoelaces, and hair length led to details of running plays, handling the ball, and scoring points—hundreds of small things done exactly as Coach Wooden wanted them done.

Everything was related to everything else; nothing was left to chance. Sloppiness was not allowed in anything, not in passing, shooting, or trimming your fingernails and tucking in your jersey.

Coach Wooden taught that great things can only be accomplished by doing the little things right. Doing things right became a habit with us. Habits stand up under pressure.

Big things are accomplished

only through the perfection

of minor details.

What It Means

Leadership often places such emphasis on reaching a distant and lofty goal (annual sales results in business; winning a championship in sports) that inadequate attention is paid to what it takes to get there—the day-by-day, minute-to-minute relevant details of how you do your job.

Sloppiness in tending to details is common—the norm—in sports and in most organizations. When it occurs, blame rests with you, the leader, not with those in the organization.

High performance is achieved only through the identification and perfection of the small but relevant details, little things done well.

Those under your leadership must be taught that little things make big things happen. First they must be taught that there are no big things, only a logical accumulation of little things done at a high standard of execution.

At UCLA John Wooden worked hard to ensure that standards—the norm—in the area of details were set extremely high. “Normal” was abnormally high.

Minor details, |

Outside observers and even some players thought the hundreds of specifics he selected for attention and perfection were foolish. Coach Wooden knew that those details—for example, putting on sweat socks correctly—were the foundation of future success and competitive greatness. Your ability to see this profound connection in your own work is essential to good leadership.

While Coach Wooden strove for perfection, “perfectionist” is not a description he would choose for himself. Perfection, he believes, is not attainable by mortal man. Striving for it with utmost effort, however, is attainable. Thus, he was relentless in looking for ways to improve performance. When he identified something that could move a team closer to perfection, he taught them how to do it.

No relevant detail is too small to be done correctly.

I consider each detail like a rivet in the wing of an airplane. Remove one rivet from the wing and it makes no difference. Remove enough of them, however, and the wing falls off.

I didn’t want anything to fall off when it came to the performance of the UCLA Bruins basketball team in practice or in games. Thus, every detail that was relevant was important and deserved to be done the right way.

Just as there is a correct way to put on sweat socks, there is a correct way of executing everything in basketball. There is a correct way of doing every job in every organization.

For me, there isn’t an “approximate” way to shoot a jump shot. There is an exact and precise method for doing it, one that affords the best chance for making the shot with allowances for the specific situation. And this is true for all other aspects of playing the game.

My fervor to see that relevant details were perfected in all areas was intended to set the tone, in style and in substance, for how the UCLA Bruins conducted business. Our standards were very high in the execution of relevant details. Most observers saw only the trophy. Few comprehended the magnitude of perfected details preceding the trophy.

I love to see little things done correctly. In my experience, that may be as close to anything that I can identify as being “the secret of success”: little things done right.

COACH WOODEN’S X’S AND O’S: |

LITTLE THINGS MAKE BIG THINGS HAPPEN |

• There are no big things; only an accumulation of little things that must be done well. |

• Details are like rivets in the wing of an airplane. Remove enough of them and the wing falls off. |

• Success starts from the ground up. Understand the relationship between “socks” and success. |

• Talent must be nourished in an environment of high performance standards. Sloppiness breeds sloppiness. When it comes to details, teach good habits. |

LEADERSHIP LESSON #7: MAKE EACH DAY YOUR MASTERPIECE

What I Learned

The South Bend Central team bus was scheduled to leave for our game against Mishawaka High School at exactly 6 p.m. All of us players were in our seats and ready to go except for two guys. They happened to be the co-captains of our team, the South Bend Central Bears. Probably our best players.

“Driver, what time do you have,” Coach Wooden asked when he stepped on board the bus. The driver looked at his watch and said, “It’s exactly 6 p.m., Coach.” Coach Wooden replied, “Well, that’s what time my watch says, too. I guess it must be 6 p.m.” He looked hard at those two empty seats and said to the driver, “Let’s go.” Coach left our two most valuable players behind. Nobody was late after that. The lesson was passed on from team to team each year. Time meant a lot to Coach Wooden.

Activity to produce real results must be organized and

executed meticulously. Otherwise, it’s no different from

children running around the playground at recess.

What It Means

There is not enough time. A leader must be very astute in using time productively and teaching those in the organization to do the same. John Wooden understood he had exactly 210 hours of practice time to accomplish his teaching goals (105 practices, each two hours in length). Or, as journalists and fans would say, Coach Wooden had 210 hours to win a national championship—12,600 minutes of actual practice time during the regular season.

Coach Wooden placed great value on every single one of those 12,600 minutes; each was a never-to-be-regained opportunity to teach the team what they needed to know to achieve Competitive Greatness, to outscore the competition.

Time, used correctly, is perhaps your most important asset. Take it away and you have nothing. Wasting a single moment became painful for him, like throwing a gold coin into the ocean never to be recovered.

John Wooden’s own appreciation for time may have begun with his father’s advice in the Seven-Point Creed: “Make each day your masterpiece.” It was Joshua Hugh Wooden’s way of reminding his son to use time wisely, not wastefully. Time is invisible. Its effects are not.

If you do not |

Only when you fully comprehend the significance of a single minute will you begin to treat the hour with respect. You will notice that successful leaders do not disrespect time.

Coach Wooden strove to make each meeting a masterpiece, each practice perfect. This came from his understanding that how you practice is how you play—in sports and elsewhere. He taught himself the mastery of using time to its greatest advantage.

One of the very few rules I enforced from my first day of coaching until my last was as follows: “Be on time.” Players—even assistant coaches—who broke this rule faced serious consequences.

Being late showed disrespect for time. I felt that one of the ways I could signal my own reverence for time was to insist on punctuality. And, to be punctual myself.

If a player appeared to be taking it easy during practice, not giving it everything he had, I told him sternly, “Don’t think you can make up for it by working twice as hard tomorrow. If you have it within your power to work twice as hard, I want you to do it right now.” This was another way of telling them not to waste time; to make this practice a masterpiece.

I believe effective organization of time—budgeting and managing time—was one of my assets as a coach. I understood how to use time to its most productive ends. Gradually, I had learned how to get the most out of a minute. In return, each minute gave back the most to our team.

I was never the greatest X’s and O’s coach around. Never. But I was among the best when it came to respecting and utilizing time. I valued it, gave it respect, and tried to make each minute a masterpiece.

It’s what you learn |

LEADERSHIP LESSON #8: THE CARROT IS MIGHTIER THAN A STICK

What I Learned

Coach Wooden expected you to be really good. Being really good was normal. He didn’t think we needed to be complimented for doing what was normal.

However, as players, we knew we were rising to a greater level when we’d see that little smile on his face. When four guys touched the ball in two seconds and the fifth guy hit a lay-up, man, what a feeling!

Punishment invokes fear. I wanted a team whose

members were filled with pride, not fear.

I’d look over and see a nod, a little wink of approval from my coach. I’m telling you a chill would run down my spine. He was saying in his own way, “You just went beyond really good to being great.” Then he would blow his whistle and say, “Now do it again. Faster.”

What It Means

A leader has a simple mission: to get those under his or her supervision to work at their highest level of ability in ways that best serve the team. Your skills as a leader who can motivate determine if and to what degree this occurs.

There are times when severe censure or penalty may be effective. Most often, however, a leader resorts to punishment because he lacks an understanding of its limitations as well as the skills necessary to create motivation based on pride, not fear.

John Wooden came to the conclusion that when choosing between the carrot and the stick as a motivational tool, the well-chosen carrot was almost always more powerful and long-lasting than the stick.

Give me 100 |

Common carrots in business include money, of course, advancement, awards, recognition, a corner office, a more prominent role on the team or in the organization. Carrots come in many forms.

However, Coach Wooden believes there is perhaps no stronger form of motivation—no better carrot—than approval from someone an individual truly respects, whose approval they seek.

He explains it like this: “I prefer to give a ‘pat on the back’ as a motivational tool, although sometimes the pat must be a little lower and a little harder.”

Sincere approval instills pride. Punishment invokes fear. He wanted a team whose members were filled with pride rather than fear.

Pride in the team and its effort is a fundamental component of Competitive Greatness in the philosophy of John Wooden. Wise use of the carrot can facilitate this, especially in combination with prudent use of the stick.

The fear and ill feelings that arise from intimidation, punishment, and cruel words—common practices with dictator-style leaders—have less power than sincere praise.

It is very hard to influence in a positive and long-lasting way when you antagonize someone.

Commendations and criticism exist, of course, within a framework of expectations—rules—regarding behavior from those in your organization.

When I was just starting out, I had lots of rules and very few suggestions. The rules were spelled out in black and white, and so were the penalties for breaking them.

When a player broke one of my rules, the punishment was automatic, enforced without discussion. And the punishment was often severe; in retrospect, often too severe.

Eventually I came to recognize that common sense is needed in deciding when and how penalties should be applied. Over the years I changed from having lots of rules and few suggestions to lots of suggestions and fewer rules.

To a large degree I replaced specific rules and penalties with strong suggestions and unspecified consequences. This gave me much greater discretion and allowed for more productive responses to misbehavior.

I came to believe as a coach and leader that if I conducted myself in a manner that earned the respect of those under my leadership, this same feeling would exist in them. When it did, I would gain one of the most powerful leadership tools available to a leader, namely, trust. Why? Because with respect comes trust by those on the team.

I tried hard to earn their respect and trust. Subsequently, when I gave my nod of approval, a wink, a pat on the back, it meant something. In fact, it meant a lot.

COACH WOODEN’S X’S AND O’S: |

THE CARROT IS MIGHTIER THAN A STICK |

• The most effective carrot is often a respected leader’s praise. It creates pride. |

• Don’t give praise if you don’t mean it. And even then don’t give it too often. |

• The purpose of criticism is to correct, improve, and change; rarely to humiliate or embarrass. |

• It is difficult to effect positive change when you antagonize. |

LEADERSHIP LESSON #9: MAKE GREATNESS AVAILABLE TO EVERYONE

What I Learned

BY DOUG MCINTOSH

UCLA VARSITY, 1964–66;

TWO NCAA NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS

“You can always do more than you think you can.” That’s the biggest thing I got from Coach Wooden’s teaching. There’s always more inside if you’re willing to work hard enough to bring it out.

Most of the time we don’t recognize we have great potential inside. Coach brought out the potential in people. He taught mental readiness: “Be ready and your chance may come. If you are not ready, it may not come again.”

Thus, he made me see there are no small opportunities. Every opportunity is big. If you only play for two minutes, make it the best two minutes possible.

Each member of |

That’s your opportunity, whether in basketball or in life. Be ready; make the most of it. It may not come again.

What It Means

John Wooden will not single out a “greatest UCLA player” or “greatest UCLA team.” Who’s #1? He will not say because it runs contrary to his concept of success; specifically, that personal greatness is measured against one’s own potential, not that of someone else. Likewise, a team’s greatness is measured against itself and no other.

He wanted the individuals under his supervision—players, assistant coaches, student managers, the trainer—to understand that the kind of greatness he sought and valued was available to each and every one of them: “Give me the best you’ve got. That’s all I ask.” Each member of the team understood they could achieve greatness by doing what he asked. It was attainable by doing their job, fulfilling their role, at the highest level of their effort and ability. Success—Competitive Greatness—was available to everyone on every team ever coached by John Wooden.

Coach Wooden asked a player such as Bill Walton to strive to achieve his own potential—his own greatness—just as he wanted head manager Les Friedman to seek his own personal best in doing the job assigned.

John Wooden recognized that Walton’s contribution to the team could be more valuable than that of the eighth man on the bench or the head manager, but his true belief, deeply felt, was that each individual under his supervision could achieve personal greatness. Bill Walton might be more valuable and difficult to replace, but his potential for Competitive Greatness as measured by Coach Wooden was exactly the same for every individual on the team. This was a concept that he worked ceaselessly to instill in the minds of everyone he coached.

“Make sure you |

When leaders instill the belief that the opportunity for personal greatness exists within every job, every role, and each person on the team, they will find themselves in charge of extraordinary achievers and motivated and most productive organizations.

For this reason, Mr. Wooden has always been strongly against retiring a player’s number because it, in effect, declares a particular individual as the greatest at that position. He feels this is dismissive of previous players who wore the number and achieved their own personal greatness.

Istated the following very clearly in my teaching: “In whatever role I assign you, execute your responsibilities to the very best of your ability.” Whether as a nonstarter or a star, I called on each to seek his own potential, his own greatness, not that of someone else.

For an organization to succeed, all members must achieve personal greatness; each in their own role that helps the team; each striving to give their job the best they have.

When all members of an organization strive for personal greatness and derive pride from the knowledge that their effort and performance contribute to the good of the group, you will unleash most powerful and productive forces.

Let the ambitious individual know that before advancing, they first must do their assigned role to the best of their ability. Let the overlooked individual better understand how their job benefits the team.

Remind those under your leadership that patience is required, and if they continue to improve, their chance will come, often when least expected. I cautioned ambitious players, “Be ready when your opportunity arrives or it may not arrive again.”

COACH WOODEN’S X’S AND O’S: |

MAKE GREATNESS AVAILABLE TO EVERYONE |

• A leader’s greatness is found in bringing out greatness in others. |

• Personal greatness is measured—like success—against one’s own potential, not that of someone else. |

• Opportunity for advancement comes unexpectedly. Teach those you lead to be prepared for it when it happens. And be patient. |

• Before calculus comes arithmetic. Advancement comes only with mastery of the assigned role and responsibility within the organization. |

An effective leader is

very good at listening.

And it’s difficult to listen

when you are talking.

LEADERSHIP LESSON #10: SEEK SIGNIFICANT CHANGE

What I Learned

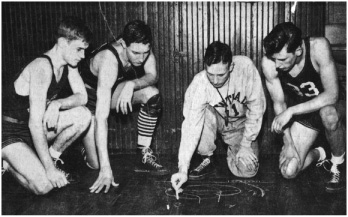

John Wooden did not want “yes-men” around him. We were encouraged to argue our points, knowing he’d come back at us strong with his own opinions. That was his way of testing how much we believed in what we were telling him and how much we knew about it.

For example, we’d debate the pivot—what was the best way to do it—for 45 minutes during a morning meeting. But he listened with an open mind, let us contribute—insisted on it. During those meetings, we didn’t just sit and take notes. He wanted interaction, ideas back and forth. What changes can we make to improve our performance?

What It Means

At the beginning of the 1961–62 season, John Wooden had been coaching basketball at UCLA for 12 years in conditions he describes as “harsh, perhaps as bad as any major university in the country.”

Never make |

The basketball facility at UCLA, the old Men’s Gym, was an environment that prevented good teaching: crowded with other sports activities during his practices, badly ventilated, without an area where he could instruct the team privately, and so small the team had to play “home games” at local junior colleges.

When it came to assessing the possibility of winning a national championship, he felt there was no chance that UCLA would be able to go all the way. Too much was working against the Bruins. First and foremost, the “near-hardship” conditions at UCLA’s gym diminished his potential for teaching.

How did this all affect his perspective as a coach? While circumspect in describing it, he suggests that perhaps it limited his thinking regarding the potential results available to his team in the national tournament. That is, winning a championship was not possible. However, events in the 1961–62 season changed his viewpoint completely, removed a subconscious barrier he may have imposed on himself, and set change in motion that would eventually produce 10 national championships and a basketball dynasty

What happened is a good lesson in how we can limit ourselves without even knowing it—how we can say “no” when we should be asking “how?”

In 1961–62 the UCLA Bruins advanced to the Final Four before losing in the final seconds to Cincinnati 72–70. A “phantom foul” for charging was called on the Bruins and Cincinnati gained possession of the ball and won the game.

Coach Wooden recognized that despite the primitive practice conditions at UCLA, the Bruins had come very close to winning a national championship.

This was a revelation. John Wooden recognized that it was time to seek significant change, to stop limiting his view of what the team might accomplish.

Once I realized that the Men’s Gym did not preclude winning a national championship, it seemed to open my mind, took the blinders off. I began an intense and comprehensive review of what I was doing and how I could do it better. I began searching for changes that would allow UCLA to consistently be more competitive in post-season play.

On the plane ride back from the tournament loss against Cincinnati in Louisville, assistant coach Jerry Norman began making his case as to why I should reconsider using a full court defense—the Press—in the upcoming season and beyond.

I listened carefully to what he said, even though I had heard and ignored it in previous years. This time, for reasons related to our near-win against Cincinnati—having the blinders removed from my eyes—I was really listening, and instead of saying “no” I said “yes.” It was a significant change, and I made it.

The Press ultimately became a trademark of UCLA basketball and contributed to our run of championships.

It took UCLA’s surprising appearance in the Final Four and a near-victory against Cincinnati for me to quit making excuses, to stop blaming the Men’s Gym for our results. I’m pleased that it happened. I am not pleased that it was necessary.

Make each day |

LEADERSHIP LESSON #11: DON’T LOOK AT THE SCOREBOARD

What I Learned

As a pro with the Milwaukee Bucks, absolutely nothing else mattered but winning. If you missed a shot or made a mistake, you were made to feel so terrible about it because all eyes were on the scoreboard.

On the other hand, Coach Wooden didn’t talk about winning—never. His message was to give the practice the best you’ve got; give the game the best you’ve got. “That’s the goal,” he would tell us. “Do that and you are a success. If enough of you do it, our team will be a success.” He teaches this, he believes it, and he taught me to believe it.

Winning was not mentioned—never—only the effort, the preparation, doing what it takes to bring out your best in practice and games. Let winning take care of itself. And it did.

What It Means

John Wooden kept a sealed envelope in his UCLA office that contained a slip of paper with predictions for game results on it for the upcoming season. Those predictions, filled in before the start of the season and filed away in a drawer, were as close as he came to worrying about what the scoreboard would show in future games; whether UCLA would beat some other team.

He wanted players to do likewise: to forget about the scoreboard and focus on doing their job at the highest possible level in practice and in competition. The score will take of itself. Focus on the present effort, not the future result.

An effective leader determines what occupies the organization’s attention, what those individuals work on and worry about. This process begins with what you, the leader, are preoccupied with.

The scoreboard? Championships? A sales quota? The bottom line? As a day-to-day preoccupation, they’re a waste of time because they steal attention and effort from the present and squander it on the future. You control the former, not the latter.

You can’t do |

An organization—a team—that’s always looking up at the scoreboard will find that a worthy opponent will steal the “ball” out from under you.

Coach Wooden’s basic philosophy was to prepare for each opponent in the same way; respect all, fear none, and concentrate on teaching the Bruins to execute his system at their highest level. Teaching, learning, and execution are all done in the present moment. He says, “I didn’t think that talking about winning all the time would increase our chances of doing so.”

Thus, he never scouted other teams because he believed the Bruins were better off letting the opponent do the scouting and constant changing. He felt the players under his supervision would be stronger doing the same thing over and over—his system executed at the highest possible standard—than trying to change each week depending on who the opponent might be. There were exceptions to this, of course, but very few.

John Wooden focused almost entirely on improvement in the present moment. He let the score—winning—take care of itself.

Don’t let yesterday take up too much of today.

If you want to extend a winning streak, forget about it. If you want to break a losing streak, forget about it. Forget about everything except concentrating on the very hard work and intelligent planning necessary for never-ending improvement. Don’t keep looking at the “scoreboard,” the won-lost record, or the ongoing results in whatever form they may take. It removes your mind from the most important task, namely, figuring out how to improve the performance of your organization. Whether you are ahead or behind, on a winning streak or a losing streak, what matters most is your focus on improvement. The “scoreboard” in all its various forms is a siren that beckons, but only distracts and diminishes our attention to incessantly seeking ways to improve.

As the leader, my job was to help each player accomplish this, in part, by getting them to block out the future, the standings, or whatever they hoped the scoreboard might show at the end of a game.

It was a goal I never sealed in an envelope and filed away in my desk.

COACH WOODEN’S X’S AND O’S: |

DON’T LOOK AT THE SCOREBOARD |

• Worry about today’s effort, not tomorrow’s results. |

• Watching the “scoreboard” is habit-forming. Break the habit. |

• Define your dreams, hopes, and aspirations. Then file them away. |

• Focus on running the race rather than winning it. |

LEADERSHIP LESSON #12: ADVERSITY IS YOUR ASSET

What I Learned

The great lesson I take from Coach Wooden is this: the best thing you can do in life is your best. You’re a winner when you do that even if you’re on the short end of the score.

Too many factors can affect the final results; the fickle finger of fate can suddenly take over. The best talent doesn’t always win, but the individual or team that goes out and does their best is a winner. That’s his philosophy. It’s what he teaches.

We had a perfect season and won the national championship in 1964. We repeated as national champions in 1965. There was no question in my mind that in 1966 we could become the first team in college basketball history to win three championships in a row. Then the fickle finger of fate pointed at us.

Injuries, sickness, and all kinds of stuff were hitting us. We didn’t even win our conference title in 1966—we had a 10–4 record and weren’t even eligible to play in the NCAA tournament and defend our title.

Be a competitor. |

Through all of the misfortune, I never heard a single complaint or excuse from Coach Wooden. He fought hard and kept telling us to keep working, never give up, do our best. And we did in spite of the fickle finger of fate.

We were a success in 1966 because of that.

What It Means

Welcome adversity. It can make you stronger, better, tougher. Your competition will be tested too. The prize goes to the competitor who best deals with adversity. This starts by not blaming your troubles on bad luck. Blaming fate—bad luck—makes you weaker. Good things come only through adversity. Good leaders understand this.

Fate plays a role in leadership. Circumstances we neither foresee, understand, nor desire can be imposed without warning on us and our organizations in what seems to be a random fashion.

In trying times it is easy to feel the fates are working directly against you—to find an excuse to let up, lose heart, then quit.

You do not control the unwelcome twists and turns that are part of life and leadership. At those difficult moments, Coach Wooden drew strength from his father’s strong example as well as his suggestion to worry only about those things over which you have control. We can’t control fate, only our response to it.

Time and time again, fate intervened in his career. He believes the following: “Things turn out best for those who make the best of the way things turn out.” He did this in 1947 when a freak snowstorm prevented officials at the University of Minnesota from calling him to offer the head coaching job of the Minnesota Gophers. This was a job he wanted very much.

Things turn out |

Instead, he went to UCLA and under “near-hardship conditions” won two national championships at the old Men’s Gym, which led to eight more titles at Pauly Pavilion. Similarly, when the rules were changed, making the dunk illegal in college basketball and thus taking away a major offensive weapon available to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Coach Wooden counseled him with this advice: “It can make you better, a more complete player.” Result? Abdul-Jabbar’s legendary sky-hook.

When knocked down by fate, a strong leader stands, takes a deep breath, and looks to make the best of the situation. They develop the ability to see adversity as usually offering a well-hidden blessing, an opportunity in disguise.

Early on I had come to believe that events in life usually work out as they should, for a reason, even if that reason is not apparent. Perhaps it was because of my faith or the example of my parents. Perhaps because of my own experiences along the way. I don’t know exactly why, but I began to better accept what fate seemed to offer and tried to make the very best of the situation, to move forward with optimism and the determination to make the most of the situation.

Those who prevail in a competitive environment look fate in the eye and say, “Welcome.” Then they move ahead without complaint, excuse, or whining.

It is inevitable in leadership and in life that events occur that seem utterly incomprehensible and unfair. While we can’t control fate, we can control how we react to the hand we’re dealt.

In leadership, your reaction is crucial because the team will follow your example.

Be a realistic optimist and remind yourself that things turn out best for those who make the best of how things turn out.

COACH WOODEN’S X’S AND O’S: |

ADVERSITY IS YOUR ASSET |

• All leaders and their organizations are visited by misfortune and bad luck. You will not be the exception to the rule. |

• “Woe is me” is not the theme song of an effective leader. |

• Adversity makes us stronger, but only if we resist the temptation to blame fate for our troubles. |

• How often have you not recognized an opportunity because it wore the disguise of bad luck? |

Goals achieved with little effort

are seldom worthwhile or long-lasting.

COMPASS CHECK

COMPASS CHECK