Chapter 8

Picking a Cryptocurrency to Mine

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Determining your goals

Determining your goals

![]() Examining the attributes of a good cryptocurrency

Examining the attributes of a good cryptocurrency

![]() Asking yourself the right questions

Asking yourself the right questions

![]() Picking the cryptocurrency that’s right for you

Picking the cryptocurrency that’s right for you

Chapter 7 talks about an easy way to get into mining: using a pool. In this chapter, we discuss preparing to mine for yourself directly, by picking an appropriate cryptocurrency to mine. Of course, getting started is much more complicated than merely picking a target, and, in fact, we recommend that you don’t actually begin mining until you finish this book, not just this chapter.

This chapter discusses the sort of factors that can help you find a good cryptocurrency to work with — one that is stable enough for you to be successful, for example. But we believe it’s a good idea to understand more before you actually get started. This chapter helps you pick an initial target cryptocurrency, but your target may change as you discover more, such as the kind of equipment you’ll need to use, for example (see Chapter 9) or more about the economics of mining (see Chapter 10). In fact, this decision-making process is a bit circular; the cryptocurrency you decide to mine determines the type of hardware you need, and the type of hardware you have (or can obtain) determines the cryptocurrency that makes sense for you to mine.

This chapter helps you to begin figuring out what cryptocurrency makes a good initial target.

Determining Your Goal

Whether you want to be a hobbyist miner or a serious commercial miner, or somewhere in between, you must ask yourself an important question before you go any further down the cryptocurrency mining path. Answering this question will enable you to properly determine which cryptocurrencies to mine, and will help you become the most successful crypto miner you can be:

What is your goal for mining cryptocurrency, and how will you reach it?

Let’s break down this question and drill deeper into its component parts, by focusing on the following questions:

- What do you want to get out of cryptocurrency mining? Maybe you’re looking to gain some insight into this whole cryptocurrency technology, or maybe you’re motivated by the possibility of windfall profits. Are you wanting to support your cryptocurrency’s ecosystem, or are you more concerned with it supporting you?

- How much capital do you plan on using? Are you planning on betting the farm, or only wanting to dip your toes in to test the water? It’s always a good idea to start small and ease into the ecosystem, but depending on your financial situation, starting small may mean something completely different for you than for another investor.

- How serious is cryptocurrency mining to you, and how much risk are you willing to take? Markets go up, markets go down, and in cryptocurrency systems, they fluctuate more frequently than traditional financial assets. It’s your savings on the line, so you should understand the risks. Consider the obligation and the stress to your life, and make sure you aren’t overcommitting before you have enough experience and a feel for the complex systems. It’s okay if you just want cryptocurrency mining to be a fun hobby experience, too!

- What is the minimum return on investment (ROI) you must meet and in what timeframe? In other words, what’s it worth to you to get involved? Are you wanting to get rich quickly, or are you trying to secure some of your value and wealth long term? You should be prepared to try something different if this ROI isn’t met, maybe even reduce the footprint of your operation. There’s no shame in scaling down or calling it quits, either. Depending on market conditions, simply purchasing a particular cryptocurrency is sometimes cheaper than mining it!

- Are you planning to measure your returns in your local fiat currency, or are you measuring your gains in the cryptocurrency asset you plan to mine? The latter option only makes sense if you have confidence in the future value of the cryptocurrency, of course. For example, many miners, during Bitcoin’s downturns, continue mining due to their strong belief that the price will increase again. As the value of the cryptocurrency drops, and some miners drop out of the business, the other miners’ incomes — measured in cryptocurrency — go up, because the block rewards are being shared among fewer miners. At such a time, the remaining miners are increasing their stock of the cryptocurrency, and even though they may be losing money if measured in terms of fiat currency, they’re okay with it because they view the cryptocurrency as an investment that will pay off in the future.

To help you answer these questions, we look at some hypothetical cryptocurrency mining stories.

First up is Kenny, an intelligent guy with a background in computers and IT. He knows his way around a datacenter, and to him, cryptocurrency mining is pretty similar to running a room full of servers. (Kenny is a tad overconfident, as running the mining equipment is only part of the battle when mining cryptocurrency.)

Kenny is looking to profit from cryptocurrency mining and views it as a challenge. With the savings from his tech job, he has set aside around $10,000 for his cryptomining venture, only a fraction of his overall savings. (We said he’s smart!) He is very serious about cryptocurrency mining, and he views the undertaking as a challenge of his intellect and skill. The minimum ROI he has decided on is 20 percent annually on every penny he puts into mining, and he plans to adjust his mining strategy every day if he’s not on track to meet this goal. Assuming moderate success on his ROI goals, he will do a full re-evaluation after one year to decide whether he continues mining.

Our second example is Cathy, a savvy investor who manages her retirement portfolio very successfully. For her, cryptocurrency mining is a way to experience and gain exposure to this new cryptocurrency technology; if it catches on, she doesn’t want to miss the boat. She wants to profit but knows that she doesn’t fully understand how cryptocurrency works, and she is excited to find out more. She is serious about doing the mining correctly and has initially set aside $500 to put toward cryptocurrency mining. She isn’t going to freak out if it ends up not working out, though. She would like to see a 10 percent ROI annually, and after six months, she will decide whether she wants to continue mining. She plans to re-evaluate her strategy every two months.

The differences to highlight here are namely the amounts invested and the expectations that both Kenny and Cathy have set for themselves. Cathy is risk-averse in her approach, but has taken a lot of pressure off herself if things don’t go as planned, by starting small with an amount she is willing to lose. She is also re-evaluating her strategy every two months, another way to reduce risk and exposure and to also make sure that she won’t be too stressed if it doesn’t work out.

Kenny has taken a riskier approach, but if he pulls it off, he will stand to profit much more than Cathy. It is important to note that Kenny has some prior experience with running networked computers, giving him a leg up and reducing some of his risk out of the gate. He is also taking a more hands-on approach with his two-week ROI evaluations, which is a good strategy because he’s putting more on the line. However, Cathy has also hedged against failure by using less of an initial investment.

Both of these miners went on to reach their goals by the end of their predetermined timelines and ended up happy that they got into cryptocurrency mining. The moral of these stories is that none of your answers to the most important question are inherently wrong, but asking these questions is critical to your success. The questions and answers will play a major role when it comes time to choose the cryptocurrencies you’ll mine and how you set up your mining rigs.

Mineable? PoW? PoS?

Many factors contribute to whether a cryptocurrency is a good choice for the aspiring miner. The first decision, of course, is whether it is possible to mine the cryptocurrency. Some cryptocurrencies cannot be mined. This is the case for some of the newest tokens and cryptocurrencies being created and promoted, especially centralized coin offerings and company-based tokens, as these are typically issued prior to release and work on systems more akin to a permissioned database than a decentralized cryptocurrency.

Furthermore, in general, we’re going to ignore proof-of-stake (PoS) cryptocurrencies (see Chapter 4). While it is possible to mine PoS cryptocurrencies, PoS mining has some inherent problems that make it less attractive to most miners. First, you need a stake; in other words, you must invest not only in your mining rig, but also in the cryptocurrency you are planning to mine. (Note, however, that the equipment needed for mining PoS cryptocurrencies is generally cheaper than for proof-of-work (PoW) cryptocurrencies. It can generally be done on regular computers, even an old piece of computer hardware you have lying around.) Before you can start, you’ll have to buy some of this cryptocurrency and store it in your wallet. Depending on the particular PoS cryptocurrency you’ve chosen, this could be a significant investment; the more you stake, the more often you will add a block to the blockchain and earn fees and perhaps block subsidies.

Secondly, the cards are already stacked against you. PoS systems have to have pre-mined currency; after all, if the system requires staking, it can’t work unless currency is already available to stake. The founders of the currency will have awarded themselves large amounts of cryptocurrency right from the get-go, so they have a head start and will dominate the process. (Again, the more you have to stake, the more often you will win the right to add a block to the blockchain.)

Thus, PoS mining has this inherent problem for newcomers: You have to invest in equipment, but the ROI will be lower for you than for the cryptocurrency’s founders, because they have a much larger stake and so will add more blocks. Hybridized proof-of-work / proof-of-state systems face many of these same issues, but with mining also involved, and so they tend to include many of the downsides of both PoW and PoS systems.

So, most mining is focused on PoW cryptocurrencies, and that’s what we focus on here. As far as cryptocurrencies that do in fact have mining implemented and proof of work embedded into their deployed systems, we walk through a few factors that would make some cryptocurrencies better to mine compared to others.

Researching Cryptocurrencies

If you want to go deep and find out more about a cryptocurrency, you’re going to need a few information sources. In this section, we look at a number of ways to uncover everything you need to know about a particular cryptocurrency.

Mining profitability comparison sites

So here’s the first type of information source, which provides a shortcut around the whole “Is it mineable?” question. Refer to the mining-comparison sites. A number of these sites gather a plethora of data about mineable cryptocurrencies. Here are a few, and more will probably appear over time, so if any of these links break, do a search engine query:

- 2CryptoCalc:

https://2cryptocalc.com/ - CoinWarz:

www.coinwarz.com - Crypto-CoinZ:

www.crypto-coinz.net - NiceHash:

www.nicehash.com/profitability-calculator - WhatToMine:

www.whattomine.com

The first thing these sites do for you is to provide a list of mineable cryptocurrencies; if it’s not on this list, it’s probably not mineable, or not practical to mine. Some of these sites will have more cryptocurrencies listed than others, but in combination, they will give you a great idea of what’s practical to mine right now. (What about the brand new coin that’s coming out tomorrow? Sure, it won’t be on those lists, but for a beginning miner, that probably doesn’t matter, and in any case, consider the Lindy Effect, explained later in this chapter, in the section, “Longevity of a cryptocurrency.”)

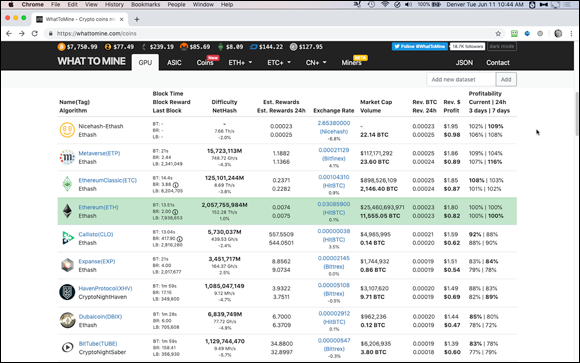

Take a look at Figure 8-1, a screenshot of WhatToMine.com. You can see that it’s listing a variety of cryptocurrencies and comparing them to mining ether on the Ethereum blockchain. There’s Metaverse, Callisto, Expanse, DubaiCoin, and so on. At the time of this writing, WhatToMine lists 62 cryptocurrencies that can be mined with graphics processing units (GPUs) and 59 that require application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs) to economically mine. (Look for the GPU and ASIC tabs near the top of the page.) In combination, these sites list around 150 different mineable cryptocurrencies.

FIGURE 8-1: The WhatToMine.com profitability comparison site.

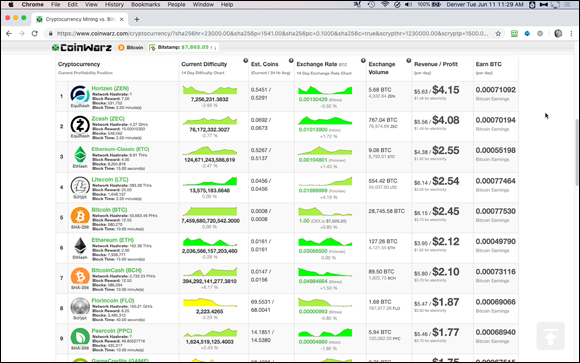

In Figure 8-2, you can see CoinWarz.com, another very popular site; CoinWarz compares the various cryptocurrencies to mining Bitcoin, rather than Ethereum. CoinWarz has a much clearer table, allowing you to easily see a few important metrics:

- Basic information related to the cryptocurrency, including the name, icon, ticker symbol (LTC, BTC, and so on), the overall network hash rate (the number of tera hashes per second; for more about hash rates, see Chapter 5), the block reward (though strictly speaking, what CoinWarz is showing is the block subsidy; the block reward is the subsidy plus the transaction fees), the number of blocks, and the time it takes on average to add a new block to the blockchain.

- A chart showing the block difficulty and how it’s changed over time.

- An estimate of how many coins you could mine each day based on your mining rig’s hash rate and the current block difficulty, and your hash rate and the average difficulty over the past 24 hours.

- The exchange rate between each cryptocurrency and Bitcoin, and how it’s changed over the last two weeks (the numbers are based on the best exchange for that cryptocurrency, which it names, so you can get the best rate when you sell your mined cryptocurrency).

- The exchange volume over the last 24 hours — that is, how much of the coin has been traded.

- The daily gross revenue, in U.S. dollars, that you would likely make (again, based on your hash rate), the cost for electricity, and the profit (or loss!) you would make each day.

- Your daily estimated earnings, denominated in Bitcoin.

FIGURE 8-2: CoinWarz.com, another very popular profitability comparison site.

Okay, so about your hash rate. As noted, some of these calculations are based on your computer equipment’s hash rate — that is, the number of PoW hashes it can carry out in a second (see Chapter 5). That’s the basic information these sites need to know to calculate how often you’re likely to win the game and add a block to the blockchain. Your hash rate is, essentially, the computational power of your computer.

These sites use default power settings, and the advantage of this approach is that you can at least get an idea of the relative profitability of the different cryptocurrencies, even if you don’t know the power of your equipment.

Now, if you do know how powerful your equipment is, you can enter that information. In CoinWarz, this information is entered into the top of the page, as shown in Figure 8-3. What are all these boxes? For each mining algorithm (SHA-256, Scrypt, X11, and so on), you see three text boxes. You enter your processor’s hash rate in the top box, in (depending on the algorithm) H/s (hashes per second), MH/s (mega hashes per second), or GH/s (giga hashes per second).

FIGURE 8-3: The top of the CoinWarz.com page, where you enter your hash rate information.

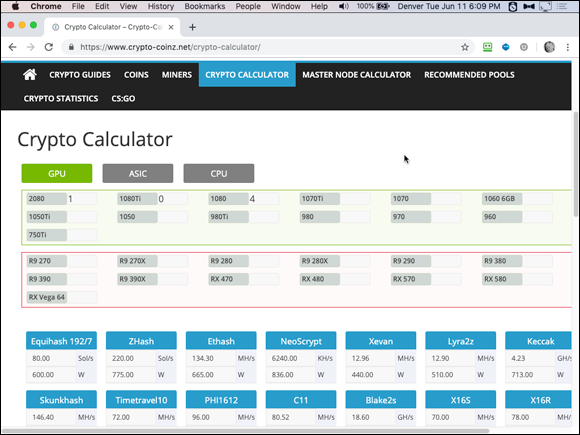

The second box is watts, the amount of electrical power your processor is going to use; and the last box is the cost of that electricity, in $/kWh, dollars per kilowatt-hour. Well, that’s a complicated subject, one that we get into in Chapter 10. Actually, some of these comparison sites provide data for common processors for you. For example, in Figure 8-4, you can see the calculator at Crypto-Coinz.net.

FIGURE 8-4: Crypto-Coinz.net actually provides hashing power information for some GPU, central processing unit (CPU), and ASIC processors.

You can see that the GPU tab has been selected, so this area is showing commonly used GPUs in the cryptocurrency mining arena. These are powerful processors, set up to manage the heat that comes from constant processing. The top box lists a bunch of NVIDIA GPU model numbers; the bottom model numbers are AMD products. Find the models you have and enter the quantity you’ll be using into the text boxes, and the site automatically enters the appropriate processing power into the boxes below.

Algorithms and cryptocurrencies

When you first start working with these sites, they may seem to be speaking a foreign language. (That’s why we suggest you spend a lot of time digging around in these sites, familiarizing yourself with the lingo, and fully understanding what’s going on.) It takes time to get used to an arena in which every other word is new to you.

Refer to Figure 8-3, for example, and you see SHA-256, Scrypt, X11, and so on. What are these? They are the particular PoW mining algorithms. For each algorithm, one or more (generally more) individual cryptocurrencies exist that use the algorithm. The following sections provide a partial list of mineable cryptocurrencies and the algorithms they use.

The lists in the following section aren’t everything; more algorithms, and more mineable cryptocurrencies, exist, but you can assume that if they’re not on at least one of the comparison sites, they’re not worth your attention. For example, at the time of this writing, a number of algorithms (X25, Keccak, SkunkHash, BLAKE2s, BLAKE256, X17, CNHeavy, and EnergiHash) are not being used by cryptocurrencies deemed worthy of these sites.

Notice another thing about the preceding list, something you may want to consider when picking a cryptocurrency that uses an algorithm that requires an ASIC. We have five ASIC algorithms listed, and below each algorithm, we have 7, 13, 8, 7, and 4 cryptocurrencies using each algorithm respectively. That is, the same ASIC — the same hardware — can be used to mine any of the cryptocurrencies using the algorithm for which the ASIC was designed.

So you could choose to mine, say, CannabisCoin, in which case you would need an X11 ASIC. If CannabisCoin went up in smoke (excuse the pun), you could switch to DASH, IDApay, or Startcoin. But if you bought an ASIC for the Scrypt algorithm, began mining one of the Scrypt cryptocurrencies, and then wanted to switch, you would have not 3 but 12 alternative choices.

Algorithms requiring a specialized ASIC

Following is a partial list of mineable cryptocurrencies and the algorithms they use. The first one, SHA-256, is the most popular algorithm — the one used by Bitcoin and all its derivatives.

- SHA-256:

- Bitcoin (BTC)

- Bitcoin Cash (BCH)

- eMark (DEM)

- Litecoin Cash (LCC)

- Namecoin (NMC)

- Peercoin (PPC)

- Unobtanium (UNO)

- Scrypt:

- Auroracoin (AUR)

- DigiByte (DGB)

- Dogecoin (DOGE)

- Einsteinium (EMC2)

- FlorinCoin (FLO)

- GAME Credits (GAME)

- Gulden (NLG)

- Held Coin (HDLC)

- Litecoin (LTC)

- Novacoin (NVC)

- Verge (XVG)

- Viacoin (VIA)

- Equihash:

- Aion (AION)

- Beam (BEAM)

- Bitcoin Private (BTCP)

- Commercium (CMM)

- Horizen (ZEN)

- Komodo (KMD)

- VoteCoin (VOT)

- Zcash (ZEC)

- Lyra2v2:

- Absolute Coin (ABS)

- Galactrum (ORE)

- Hanacoin (HANA)

- Methuselah (SAP)

- MonaCoin (MONA)

- Straks (STAK)

- Vertcoin (VTC)

- X11:

- CannabisCoin (CANN)

- DASH (DASH)

- IDApay (IDA)

- Petro (PTR)

- Startcoin (START)

Algorithms that may be mined without ASICs

The following algorithms may still effectively be mined without purpose-built, application-specific hardware, or ASICs.

- NeoScrypt:

- Cerberus (CBS)

- Coin2Fly (CTF)

- Desire (DSR)

- Dinero (DIN)

- Feathercoin (FTC)

- GoByte (GBX)

- Guncoin (GUN)

- Innova (INN)

- IQ.cash (IQ)

- LuckyBit (LUCKY)

- Mogwai (MOG)

- Phoenixcoin (PXC)

- Qbic (QBIC)

- Rapture (RAP)

- SecureTag (TAG)

- SimpleBank (SPLB)

- SunCoin (SUN)

- Traid (TRAID)

- TrezarCoin (TZC)

- UFO Coin (UFO)

- Vivo (VIVO)

- Zixx (XZX)

- Ethash:

- Akroma (AKA)

- Atheios (ATH)

- Callisto (CLO)

- DubaiCoin (DBIX)

- Ellaism (ELLA)

- Ether-1 (ETHO)

- Ethereum (ETH)

- Ethereum Classic (ETC)

- Expanse (EXP)

- Metaverse (ETP)

- Musicoin (MUSIC)

- Nilu (NILU)

- Pirl (PIRL)

- Ubiq (UBQ)

- Victorium (VIC)

- WhaleCoin (WHL)

- X16R:

- BitCash (BITC)

- CrowdCoin (CRC)

- GINcoin (GIN)

- GPUnion (GUT)

- Gravium (GRV)

- HelpTheHomeless (HTH)

- Hilux (HLX)

- Motion (XMN)

- Ravencoin (RVN)

- StoneCoin (STONE)

- Xchange (XCG)

- Lyra2z:

- CriptoReal (CRS)

- Gentarium (GTM)

- Glyno (GLYNO)

- Infinex (IFX)

- Mano (MANO)

- Pyro (PYRO)

- Stim (STM)

- Taler (TLR)

- ZCore (ZCR)

- X16S:

- Pigeoncoin (PGN)

- Rabbit (RABBIT)

- Reden (REDN)

- RESQ Chain (RESQ)

- Zhash:

- BitcoinZ (BTCZ)

- Bitcoin Gold (BTG)

- SnowGem (XSG)

- ZelCash (ZEL)

- CryptoNightR:

- Monero (XMR)

- Lethean (LTHN)

- Sumokoin (SUMO)

- Xevan:

- BitSend (BST)

- Elliotcoin (ELLI)

- Urals Coin (URALS)

- PHI2:

- Argoneium (AGM)

- Luxcoin (LUX)

- Spider (SPDR)

- Equihash 192/7:

- SafeCoin (SAFE)

- Zero (ZER)

- Tribus:

- BZL Coin (BZL)

- Scriv (SCRIV)

- Timetravel10: Bitcore (BTX)

- PHI1612: Folm (FLM)

- C11: Bithold (BHD)

- HEX: XDNA (XDNA)

- ProgPoW: Bitcoin Interest (BCI)

- LBK3: VERTICAL COIN (VTL)

- VerusHash: Verus (VRSC)

- Ubqhash: Ubiq (UBQ)

- MTP: Zcoin (XZC)

- Groestl: Groestlcoin (GRS)

- CrypoNightSaber: BitTube (TUBE)

- CryptoNightHaven: HavenProtocol (XHV)

- CNReverseWaltz: Graft (GRFT)

- CryptoNight Conceal: Conceal (CCX)

- CryptoNight FastV2: Masari (MSR)

- CryptoNight Fast: Electronero (ETNX)

- Cuckatoo31: Grin-CT31 (GRIN)

- Cuckatoo29: Grin-CR29 (GRI)

- Cuckatoo29s: Swap (XWP)

- Cuckoo Cycle: Aeternity (AE)

- BCD: Bitcoin Diamond (BCD)

- YescryptR16: Yenten (YTN)

- YesCrypt: Koto (KOTO)

The cryptocurrency’s details page

Another great place to find information about a particular cryptocurrency is on the currency’s details page at the comparison sites. The comparison sites we looked at earlier in this chapter generally link to that page. In fact, refer to the image in Figure 8-1; if you click on a cryptocurrency name, you’re taken to a details page that contains additional information about that cryptocurrency. For example, click Callisto (CLO), and you see the page shown in Figure 8-5.

FIGURE 8-5: A cryptocurrency detail page on WhatToMine.com.

This page contains stacks of information about the cryptocurrency, including statistics such as the block time (how often a block is added), the block reward, the difficulty level, and so on. It also lists mining pools that work with this particular currency (see Chapter 7).

Mining-profit calculators

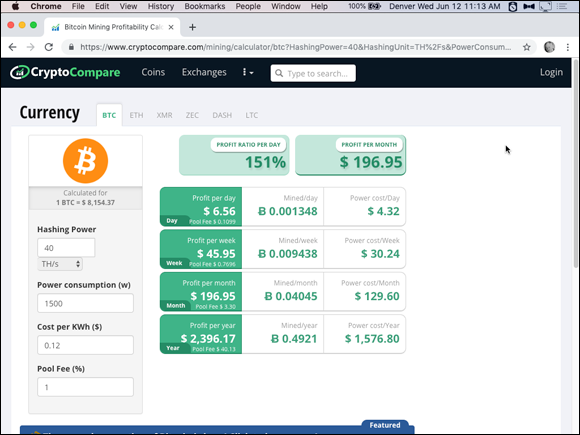

If you want to know what the profit potential is for a particular cryptocurrency, you need to work with a mining-profit calculator. The mining comparison sites generally contain these calculators, though other sites also provide individual calculators without an overall comparison tool. (www.cryptocompare.com/mining/calculator/, for example, provides calculators for Bitcoin, Ethereum, Monero, Zcash, DASH, and Litecoin.)

For example, refer to Figure 8-5. At the top of the page, you can enter your hardware’s hash rate, power consumption, and cost, along with the cost of your electricity, and the calculator will figure out how much you can make (or lose) over an hour, a day, a week, a month, or a year.

Figure 8-6 shows a simpler calculator, from www.cryptocompare.com/mining/calculator/btc, that displays potential revenue and profit from mining Bitcoin. This calculator even allows you to enter a pool fee, to include the costs of mining through a pool (see Chapter 7). This example, even though it shows you making a profit, is actually a losing proposition. (See the nearby sidebar, “Hash power envy? You’d better pool mine.”)

FIGURE 8-6: The Bitcoin calculator at CryptoCompare.com.

The cryptocurrency’s home page

Another great place to find information about a cryptocurrency in which you have some interest is, not surprisingly, the cryptocurrency’s home page (though, of course, the information you’ll find here will be biased toward optimism for the future of the currency). That’s easy enough to find. The comparison site’s cryptocurrency details pages (refer to Figure 8-5) generally have this information. You can also find this information at other sites, such as coinmarketcap.com.

GitHub

Most cryptocurrencies you’re likely to be mining have a GitHub page. GitHub is a software development platform and software repository, used by many open-source software projects. Although cryptocurrencies are not open source by definition, most of them are (in fact, any cryptocurrency you’re likely to mine is generally open source). You can see an example — the Bitcoin GitHub page — in Figure 8-7.

FIGURE 8-7: Bitcoin’s GitHub page.

How do you find the GitHub page? Again, the details page at one of the cryptocurrency sites may hold a link to the currency’s GitHub page, or it may not. You may be able to find a link to it in the currency’s home page, or you can also search for it within GitHub.com.

At GitHub, you can review the actual source code of the cryptocurrency to see how it functions, if you have the skills to do so, but you can also get an idea of how active the community is, how many people are involved, how often changes are made to the code, and so on. For a deeper dive into the specific mechanisms and intricacies involved with GitHub, refer to GitHub For Dummies (John Wiley & Sons, Inc.) by Sarah Guthals and Phil Haack.

The cryptocurrency’s Wikipedia page

Many, perhaps most, cryptocurrencies, have Wikipedia pages. These can be useful places to find general background information about a cryptocurrency, often more quickly than using other sources. These pages often provide a little history about the currency, information about the founders and the technology, controversies related to it, and so on. You won’t find them for many of the smaller, more obscure cryptocurrencies, though, and the level of detail for the ones that are there ranges from sparse to exhaustive.

You can see an example in Figure 8-8, which shows Dogecoin’s Wikipedia page. Notice the info-block on the right side, which provides a quick rundown of important information.

FIGURE 8-8: The Dogecoin Wikipedia page.

Mining forums

Finally, don’t forget the cryptocurrency mining forums, of which perhaps the most significant are the Bitcoin (BitcoinTalk.org) forums. You can find forums on numerous subjects here, related to many different Bitcoin and cryptocurrency issues. There’s a Bitcoin Mining section, as well as an Alternative Cryptocurrencies section, and within that, a Mining subsection. The Altcoin mining section has more than 800,000 posts in more than 3,000 topic areas, and so a wealth of mining information is there to be digested.

Going Deep

After you know how to find the information on a variety of these cryptocurrency systems — if it’s available, that is, because in many cases the information may be hard to find — you may want to consider several other factors.

Longevity of a cryptocurrency

To choose a cryptocurrency that is right for you, it is important to have confidence that it will be around and functioning during the period you choose to mine it, as well as the period in which you plan for the cryptocurrency to store your mining rewards.

Cryptocurrency systems that have withstood the test of time are more likely to continue to do so. There’s a theory called the Lindy Effect that states that the life expectancy of certain things, such as technology, increases as they age. (The opposite is true for living things, of course; once they reach a certain age, life expectancy declines.)

The theory, by the way, is named after a deli in New York where comedians gather each night to discuss their work. Anyway, this theory suggests that the life expectancy of ideas or technologies (nonbiological systems) is related to their current age, and that each extra duration of existence makes it more likely that the idea or technology will continue to survive. Open-source systems such as Bitcoin or other similar cryptocurrencies are constantly being upgraded and improved ever so slightly by programmers and software enthusiasts. Each code bug, or error in the system, that is found and quickly patched (a software term for fixed) will leave the system tougher and less prone to error going forward. Software systems such as Bitcoin or similar open-source cryptocurrencies can be considered antifragile, with each flaw that is discovered and subsequently fixed leading to a stronger and less fragile technology.

Let us summarize with a question: Which cryptocurrency is likely to survive longer? Bitcoin, dating back to January 2009, or JustAnotherCoin, a (hypothetical) new cryptocurrency released to the world yesterday afternoon? Bitcoin be a better bet, if you’ll excuse the alliteration. There are a couple of thousand cryptocurrencies; most are garbage, and can’t possibly survive. A new one is likely just one more JunkCoin on the garbage heap.

On the other hand, sometimes apparently stable, long-lasting systems die. Who remembers DEC, WordPerfect, or VisiCalc, for example? (We bet that many readers have no idea what these words even mean!) And sometimes new systems appear in a flash and beat out well-established competitors. (Google, anyone? Facebook?)

But, to continue with the example of technology companies, most newcomers fail; most Internet startups in the 1990s Internet bubble went out of business, for example. Most obscure cryptocurrencies will fail, too. So, in general, a long-lasting cryptocurrency, such as Bitcoin, Litecoin, or ether, is a better bet than today’s new entry into the cryptocurrency market.

How do you figure out how long the cryptocurrency has been around? It shouldn’t be too hard to find. Check the currency’s own website, its Wikipedia entry if there is one, and GitHub’s history of software commits and releases.

Hash rate and cryptocurrency security

Another important factor involved with the choice of which cryptocurrency to mine is the security encompassing the blockchain being selected to mine. You wouldn’t want to put your eggs (mining resources) in a basket (blockchain) with holes in it that cannot support the weight of your precious cargo (value).

This same idea applies to cryptocurrency systems, and security in this sense is relative. A cryptocurrency that has a low level of hash-powered proof of work is less secure than other cryptocurrencies that run on a similar consensus mechanism, as it’s more easily hacked or manipulated. This puts the cryptocurrency’s chance of surviving at risk and also puts your funds in that blockchain at risk.

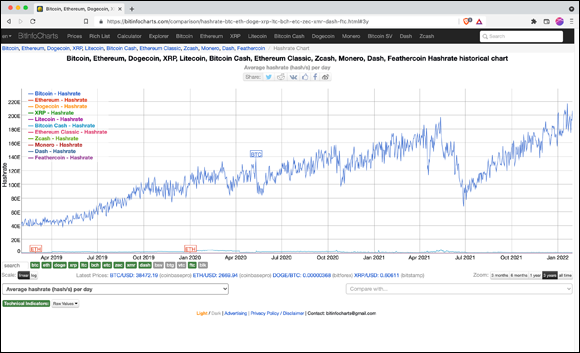

As shown in Figure 8-9, one thing you can do is select a bunch of cryptocurrencies and create a chart comparing their hash rates; see https://bitinfocharts.com/comparison/bitcoin-hashrate.html. You can also find individual hash rates from the comparison sites we look at earlier in this chapter (see the section, “Hash rate and cryptocurrency security”).

FIGURE 8-9: BitInfoCharts.com’s hash-rate comparison page.

In fact, hash rate is something you’ll find on various sites. For example, you can find the hash rate for Bitcoin, Ethereum, and Bitcoin Cash at www.blockchain.com/explorer. The pool-mining services provide hash rate statistics for the cryptocurrencies they mine, and statistics sites such as Coin Dance provide some, too (see https://coin.dance/blocks/hashrate).

Community support

Another factor to consider and weigh when selecting which cryptocurrency is right for you is community support. Network effects of cryptocurrency systems are important, and wide adoption and utilization are key metrics to look at when choosing which blockchain to mine. Are many people involved in managing and developing the cryptocurrency? (A cryptocurrency with very few people involved is likely to be unstable.) And are many people using the cryptocurrency — that is, is there much trading going on, or are people using it to make purchases?

There’s a concept known as Metcalfe’s Law that explains network effects. The idea, proposed by Robert Metcalfe, one of the inventors of Ethernet, is that a communication system creates value proportional to the square of the number of users of that particular system. Essentially, the more users on a system, the more useful — and more valuable — the network becomes.

Community support is also important in other ways. It can be measured in the form of open-source developers actively contributing to the cryptocurrency’s code repository. A healthy and robust cryptocurrency will have a diverse set of many individuals and entities reviewing and auditing the code that fortifies it.

How do you measure community support? The cryptocurrency’s GitHub page is a great start; you’ll be able to see exactly how active the development process is, and how many people are involved. The currency’s web page may give you an idea of activity, too, especially if the site has discussion groups. Another helpful tool to compare support across different networks can be found at www.coindesk.com/data, which shows a variety of rankings comparing top cryptocurrencies such as social, market, and developer benchmarks.

Knowing That Decentralization Is a Good Thing

In general, more decentralized cryptocurrencies are likely to be more stable and likelier to survive (long enough for you to profit from mining) than more centralized and less distributed cryptocurrencies.

In the cryptocurrency arena, the term decentralization is thrown around as an absolute: The system is either decentralized or it is not. This, however, isn’t exactly the case. Decentralization, in fact, can be thought of as a spectrum (see Figure 8-10), and many aspects of a cryptocurrency system fall on different parts of the decentralization spectrum.

FIGURE 8-10: The spectrum of decentralization.

A major aspect of decentralized peer-to-peer blockchain-based systems is the fact that any user can spin up a node and be an equal participant in the network. Here are a few other factors that can also be used to rank cryptocurrencies on the decentralization spectrum.

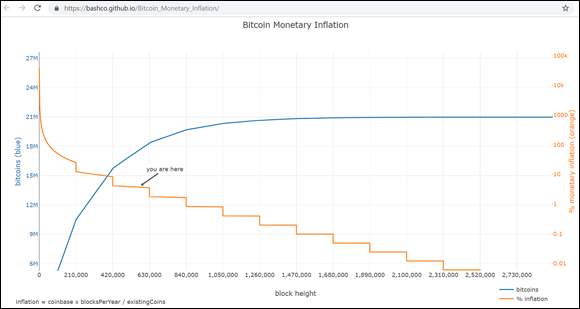

- Initial coin distribution and coin issuance: For a proof-of-work cryptocurrency with a predetermined issuance schedule, the distribution of coins can be considered fairer than a system in which a high percentage of the coin issuance was pre-mined and distributed to a select few insiders. This would place pre-mined cryptocurrencies further toward the centralized spectrum than fairer and more decentralized coin-distribution models. To view a detailed breakdown of the Bitcoin network’s coin issuance schedule, see Figure 8-11, which shows the interactive chart being dynamically created at

https://bashco.github.io/Bitcoin_Monetary_Inflation/. (Go to the website and run your mouse pointer along the lines to see the exact numbers at any time.) The stepping line shows the block subsidy halving every 210,000 blocks, or roughly every four years. The upward curve line shows the amount of Bitcoin in circulation at any time. As for researching other cryptocurrencies, the comparison sites will show how often the currency’s coins are issued. - Node count: The nodes are the gate keepers of valid transaction data and block information for blockchain systems. The more active nodes there are running on the system, the more decentralized the cryptocurrency. Unfortunately, this is a tricky one; it’s probably pretty difficult to find this precise information for most cryptocurrencies.

- Network hash rate: The level of the cryptocurrency’s hash rate distribution among peers is also an important decentralization measurement for PoW cryptocurrencies. If only a few companies, individuals, or organizations (such as mining pools) are hashing a blockchain to create blocks, the cryptocurrency is relatively centralized. See the earlier section, “Hash rate and cryptocurrency security.”

- Node client implementations: Multiple versions of client, or node, software exist for many of the major cryptocurrencies. For example, Bitcoin has Bitcoin Core, BitCore, BCOIN, Bitcoin Knots, BTCD, Libbitcoin, and many other implementations. Ethereum has geth, parity, pyethapp, ewasm, exthereum, and many more. Cryptocurrencies with fewer client versions may be considered more centralized than those with more versions. You can probably find this information at the cryptocurrency’s GitHub page and on its website. For an interesting view of the Bitcoin network client versions for nodes on the network, navigate to the following site:

https://luke.dashjr.org/programs/bitcoin/files/charts/branches.html. - Social consensus: Social networks of users and the people participating in these cryptocurrencies are also very important in regard to the cryptocurrency decentralization spectrum. The larger the user base and the more diverse technical opinions on the system, the more robust the software and physical hardware are to changes being pushed by major players in the system. If the social consensus of a cryptocurrency is closely following a small set of super users or a foundation, then the cryptocurrency is, in effect, more centralized. More control is in the hands of fewer people, and the system is more likely to experience drastic changes in its rules. An analogy can be seen in sporting events; the rules (consensus mechanisms) are not changed by the referees (users and nodes) halfway through the competition. The number of active addresses in the cryptocurrency’s blockchain provides a good metric indicating social consensus and the network effect. This shows the number of different blockchain addresses with associated balances. This metric isn’t perfect, as individual users can have multiple addresses, and sometimes many users have coins associated with a single address (when utilizing an exchange or custodial service that stores all its clients’ currency in one address). However, the active addresses metric can still be a helpful gauge to compare cryptocurrencies — more addresses means, in general, more activity and more people involved. A helpful tool to find cryptocurrency active address numbers can be found at

https://coinmetrics.io/charts/; choose Active Addresses in the drop-down list box on the left, and select the cryptocurrencies to compare using the option buttons at the bottom of the chart (see Figure 8-12). For smaller cryptocurrencies, this information may be hard to find, but the data would be accessible via a cryptocurrency’s auditable blockchain. - Physical node distribution: With cryptocurrencies, node count is important, but it is also important that those nodes not be physically located in the same geographical area or on the same hosted servers. Some cryptocurrencies have the majority of their nodes hosted on third-party cloud services that provide blockchain infrastructure, such as Amazon Web Services, Infura (which itself uses Amazon Web Services), DigitalOcean, Microsoft Azure, or Alibaba Cloud. Systems with this type of node centralization may be at risk of being attacked by these trusted third parties. Such systems are more centralized than purer peer-to-peer networks with large node counts that are also widely geographically distributed. A view of the Bitcoin network node geographical distribution can be found at

https://bitnodes.earn.com/. For the smaller cryptocurrencies, this information may be harder to find. - Software code contributors: A broad range of code contributors to the client software implementations — and code reviewers — is important for the decentralization of a cryptocurrency; the larger the number of coders, the more distributed and decentralized the cryptocurrency can be considered. With fewer contributors and reviewers, errors in the code can be more prevalent and intentional manipulation more possible. With larger numbers of reviewers and coders, mistakes and malfeasance are more easily caught. The developer count and activity on various cryptocurrency code repositories can be gleaned by exploring their GitHub pages. For Bitcoin’s core repository, the link to find out more details is found at

https://github.com/bitcoin/bitcoin/graphs/contributors. As an example, Ethereum averages just over 200 active repository developers per month, while the Bitcoin network averages just under 100. For most other cryptocurrency networks, that number is much lower. On average, at the time of this writing, about 8,000 developers are currently working on thousands of different cryptocurrency projects each month.

FIGURE 8-11: Chart from GitHub depicting the coin issuance schedule and inflation rate for Bitcoin. It has served as a model for most proof-of-work distribution schedules.

FIGURE 8-12: Coinmetrics.io compares active-address quantities between different cryptocurrencies (and provides many more statistics).

Finding Out It’s an Iterative Process

Choosing a cryptocurrency to mine is an iterative process; it’s a combination of all the factors we cover in this chapter, the hardware you’re able to obtain (see Chapter 9), and the economics of the mining (Chapter 10). The economics will affect which mining hardware you can afford to buy, and what you can afford to buy will affect which cryptocurrency you choose. If you haven’t already, we suggest that you read Chapters 8 and 9 to find out how all these factors fit together, and put off the final decision until you do.

All these sites work differently. We strongly recommend that you try a few, pick one or two that you really like, and then spend an hour or two digging around and figuring out how they function. They provide a huge amount of information, in many different formats, so play a while and really get a handle on them.

All these sites work differently. We strongly recommend that you try a few, pick one or two that you really like, and then spend an hour or two digging around and figuring out how they function. They provide a huge amount of information, in many different formats, so play a while and really get a handle on them. Many of these cryptocurrency systems are distributed with the aim of decentralization. This means that for most of these systems, no single party controls them, so many sites may claim to be the home page for that particular peer-to-peer cryptocurrency, with some having more validity to that claim than others. Always do plenty of research and tread lightly.

Many of these cryptocurrency systems are distributed with the aim of decentralization. This means that for most of these systems, no single party controls them, so many sites may claim to be the home page for that particular peer-to-peer cryptocurrency, with some having more validity to that claim than others. Always do plenty of research and tread lightly. Developer support is critical to the longevity and robustness of a cryptocurrency system. Note that many cryptocurrency systems created and issued by companies or consortiums are not open source, not mineable, and do not have a wide range of code auditors outside of the company reviewing and revising their walled-garden systems.

Developer support is critical to the longevity and robustness of a cryptocurrency system. Note that many cryptocurrency systems created and issued by companies or consortiums are not open source, not mineable, and do not have a wide range of code auditors outside of the company reviewing and revising their walled-garden systems.