Coping With Emerging and Advanced Market Risks

Overview

For the past six years or so, advanced economies have been exposing international investors to a lot of risk, from the U.S. economy trembling over its fiscal cliff and the EU struggling to control the eurozone crisis, to Japan seemingly sunk into permanent stagnation. Hence, it would be easy to conclude that the biggest global risks, as of now, would come from these advanced economies.

Yet, that’s not what Eurasia, a political risk consultancy group, argues. In its predictions for 2013,1 the group puts emerging markets at the top of their risk rankings. That’s because, they argued, the advanced economies have proved in recent years that they can manage crises. Conversely, there are several risks suggesting emerging markets will likely struggle to cope with the world’s growing political pressures. Eurasia argues that

But…with an absence of global leadership and geopolitics very much “in play,” everyone will face more volatility. That’s going to prove a much bigger problem for emerging markets than the developed world. In 2013, the first true post-financial crisis year, we’ll start to see that more clearly.*

People tend to think of emerging markets—including the so-called BRIC nations of Brazil, Russia, India, and China—as immature states in which political factors matter at least as much as economic fundamentals for the performance of markets.

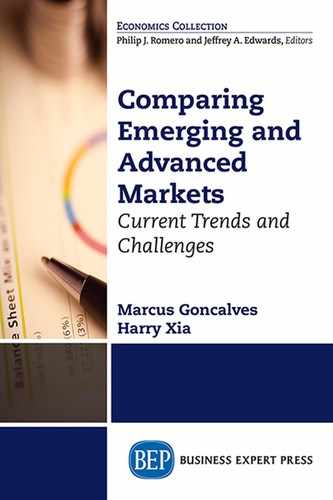

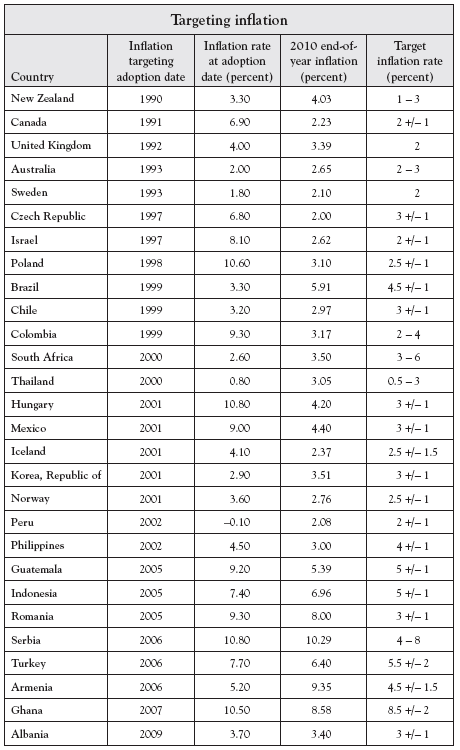

It was even before the recent global financial crisis that growth of emerging markets had shaken the foundations of faith in free markets, which appeared to have fully, and finally, established the dominance of the liberal economic model tested by the past success of advanced economies. The model’s fundamental components are private wealth, private investment, and private enterprise. Figure 4.1 illustrates the significant growth these regions have experienced in the past decade or so.

Figure 4.1 Emerging markets led by BRIC have demonstrated stronger growth than the advanced economies2

Source: IMF.

To combat the economic and social challenges surfaced from the global financial recession, both advanced and emerging economies have injected politics and political motivations, on a scale we haven’t seen in decades, into the performance of global markets. Massive state interventions, including currency rate manipulation, inflation targeting, state capitalism, and economic nationalism in certain areas, have been accelerated in markets as world-wide governments and central banks try to stimulate growth and rescue vulnerable domestic industries and companies.

However, such a shift doesn’t guarantee a panacea for all economic problems. Along with its own risks and intensified confrontation, emerging markets’ most tumultuous growth model seems to have more or less reached a turning point. Growth rates in all the BRICs have dropped while the United States and EU are facing possible secular stagnation; that calls for a more thorough search for better measures and solutions.

Currency Rate

Currency war, also known as competitive devaluation of currency, is a term raised as the alarm by Brazil’s Finance Minister Guido Mantega to describe the 2010 effort by the United States and China to have the lowest value of their currencies.3

The rationale behind a currency war is really quite simple. By devaluing one’s currency it makes exports more competitive, giving that individual country an edge in capturing a greater share of global trade, therefore, boosting its economy. Greater exports mean employing more workers and therefore helping improve economic growth rates, even at the eventual cost of inflation and unrest.

The United States allows its currency, the dollar, to devalue by expansionary fiscal and monetary policies. It’s doing this through increasing spending, thereby increasing the debt, and by keeping the federal funds rate at virtually zero, subsequently increasing credit and the money supply. More importantly, through “quantitative easing” (QE), it has been printing money to buy bonds, with its peak at $85 billion a month.

China tries to keep its currency low by pegging it to the dollar, along with a basket of other currencies. It keeps the peg by buying U.S. Treasuries, which limits the supply of dollars, thereby strengthening it. This keeps Chinese yuan low by comparison. More recently, the yuan has taken a violent turn toward devaluation against the dollar since February 2014. Obviously, both United States and China benefitted from currency rate manipulation to secure their leading positions in international trade.

According to the WTO International Trade Statistics 2013 and as depicted in Figure 4.2, the United States was the world’s biggest trader in merchandise by then†, with imports and exports totaling $3,881 billion in 2012. Its trade deficit amounts to $790 billion, or 4.9 percent of its GDP. China followed closely behind the United States, with merchandise trade totaling $3,867 billion in 2012. China’s trade surplus was $230 billion, or 2.8 percent of its GDP.

Figure 4.2 Leading export and import traders of 2012

Source: International Trade Statistics 2013 (WTO).

Through manipulation of currency rate, devaluation also is used to cut real debt levels by reducing the purchasing power of a nation’s debt held by foreign investors, which works especially well for the United States. But such currency rate manipulation has invited destructive retaliation in the form of a quid pro quo currency war among the world’s largest economies.

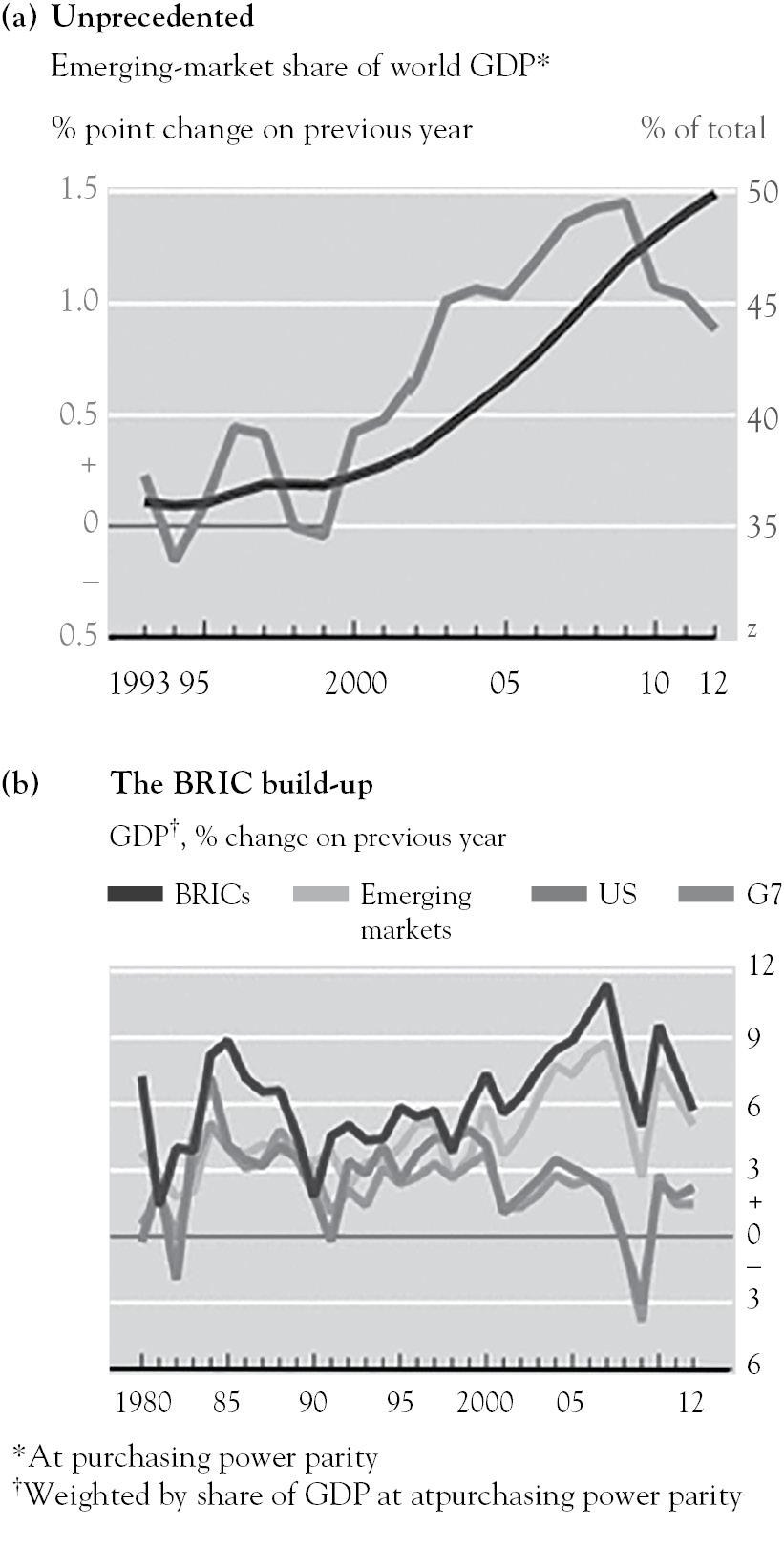

A joint statement issued by the government and the Bank of Japan (BOJ) in January 2013 stated that the central bank would adopt a two percent inflation target. Later, Haruhiko Kuroda, the BOJ’s governor announced the BOJ’s boldest attempt so far to stimulate Japan’s economy and end years of deflation. The bank intends to double the amount of money in circulation by buying about ¥13 trillion yens in financial assets, including some ¥2 trillion yens in government bonds, every month as long as necessary. BOJ’s effort together with the months of anticipation that preceded it has knocked the yen down sharply against the dollar and other major currencies (as shown in Figure 4.3) and sparked a rally in Japanese shares. It also has further reignited fears of currency tensions around the globe.

Figure 4.3 U.S. dollar exchange rates against currencies of selected countries, January 2005–March 2014. Indices of U.S. dollars per unit of national currency, 1 January 2005 = 100.

Sources: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

The EU made its move in 2013 to boost its exports and fight deflation. The ECB, after cutting its policy rate to 0.5 percent in May, lowered its rate further to 0.25 percent on November 7, 2013. This immediately drove down the euro-to-dollar conversion rate to $1.37 dollars.

Brazil and other emerging market countries are concerned because the currency wars are driving their currencies higher, by comparison. This raises the price of commodities, such as oil, copper, and iron, that is, their primary exports. This makes emerging market countries less competitive and slows their economic growth.

In fact, India’s new central bank governor, Raghuram Rajan, has criticized the United States and others involved in currency wars that they are exporting their inflation to the emerging market economies.

However, condemning the currency war and the United States, BRICS, except for China, had their currencies devaluated against the U.S. dollar after the financial crisis. (See Figure 4.3)

In currency wars, exchange rate manipulation can be accomplished in several ways:

• Direct intervention—Adopted by the PBOC and BOJ, in which a country can sell its own currency in order to buy foreign currencies, resulting in a direct devaluation of its currency on a relative basis.

• Quantitative easing—Taken by U.S. Federal Reserve, in which a country can use its own currency to buy its own sovereign debt, and ultimately depreciate its currency.

• Interest rates—Exercised by BOJ, Federal Reserve, and ECB in which a country can lower its interest rates and thereby create downward pressure on its currency, since it becomes cheaper to borrow against others.

• Threats of devaluation—Used by the United States toward China, in which a country can threaten to take any of the aforementioned actions along with other measures and occasionally achieve the desired devaluation in the open market.

An important episode of currency war occurred in the 1930s. As countries abandoned the Gold Standard during the Great Depression, they used currency devaluations to stimulate their economies. Since this effectively pushes unemployment overseas, trading partners quickly retaliated with their own devaluations. The period is considered to have been an adverse situation for all concerned as unpredictable changes in exchange rates reduced overall international trade.

Control the Currency Rate and Capital Flows

To avoid a repeat of such painful history and damage to international trade caused by ongoing currency wars, Pascal Lamy, former Director-General of the WTO, pointed out in the opening to the WTO Seminar on Exchange Rates and Trade in March 2012 that “the international community needs to make headway on the issue of reform of the international monetary system. Unilateral attempts to change or retain the status quo will not work.”

The key challenge to the rest of the world is the United States policy of renewed quantitative easing, which gives both potential benefits and increasing pressure to other countries. Among the benefits would be to help push back the risk of deflation that has been observed in much of the advanced world. Avoiding stagnation or renewed recession in advanced economies, in turn, would be a major benefit for emerging markets in world trade, whose economic cycles remain closely correlated with those in the developed world (Canuto 2010). Another major plus would be to greatly reduce the threat of protectionism, particularly in the United States. The most plausible scenario for advanced country protectionism would be a long period of deflation and economic stagnation, as seen in the 1930s (Canuto and Giugale 2010).

Based on our observations, the adjustment issue has been relatively easier in other advanced economies (especially countries within the EU) that also are experiencing high unemployment and are threatened by deflation. In this situation, there could be a rationale not so much for a currency war as for a coordinated monetary easing across developed countries to help fend off deflation while also reducing the risk of big exchange rate realignments among the major developed economies (Portes 2010).

In contrast, it is more complicated for most emerging markets, such as China, that experience relatively stronger growth and higher inflationary rather than deflationary pressures. In this situation, the U.S. easing poses more challenging policy choices by creating added stimulus for capital flows to emerging markets, flows that have already been surging since 2010, and attracted both by high short-term interest rate spreads and the stronger long-term growth prospects of emerging economies.

To put currency rate and capital flows under reasonable control with the increasing pressure from U.S. monetary easing, there are three approaches suggested by the World Bank experts (Brahmbhatt, Canuto, and Ghosh December, 2010).

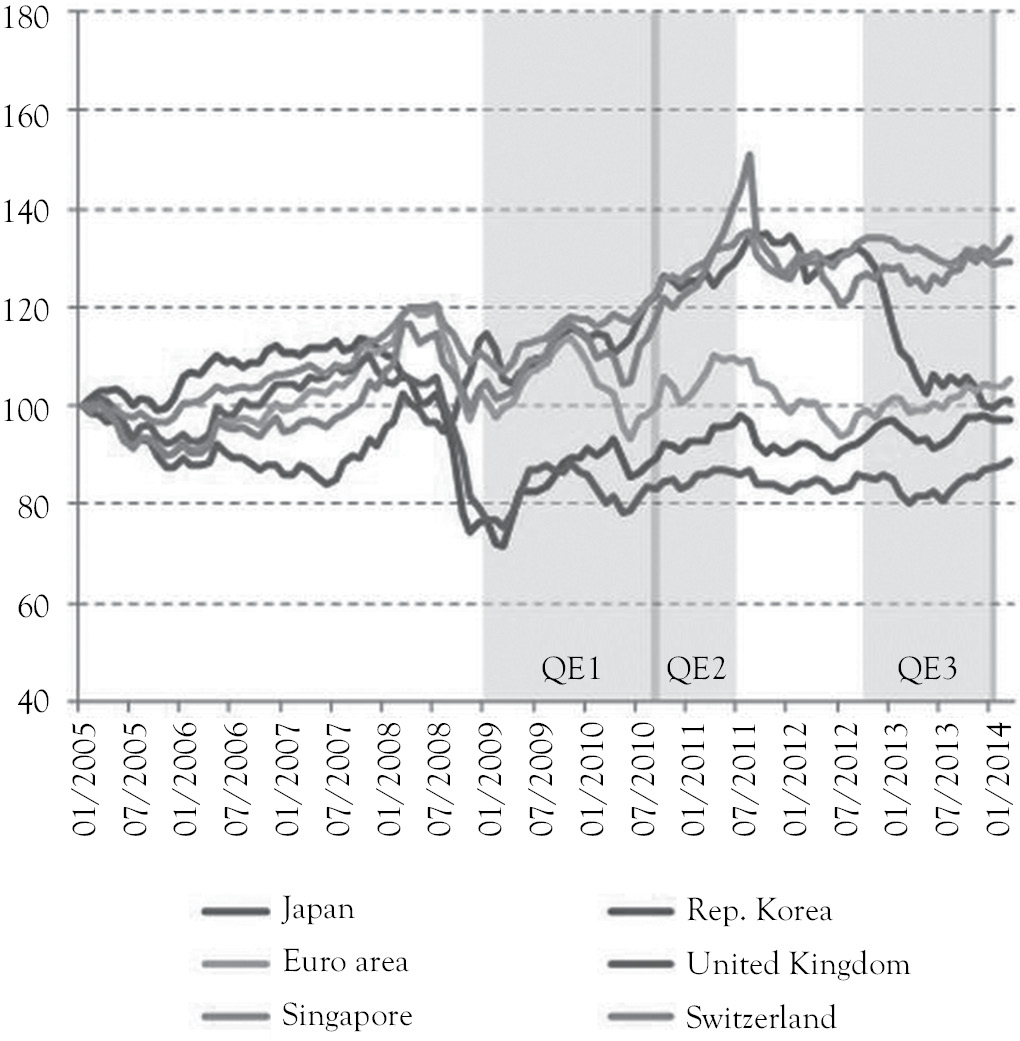

First is to maintain a fixed exchange rate peg and an open capital account while giving up control of monetary policy as an independent policy instrument. This approach tends to suit smaller economies such as Hong Kong that are highly integrated both economically and institutionally with the larger economy to whose exchange rate they are pegged. It is less appropriate for larger developing countries, such as China, whose domestic cycles may not be at the same pace as the economy (in this case the United States) to which they are pegged. Importing loose U.S. monetary policy will tend to stimulate excessive domestic money growth, inflation in the goods market, and speculative bubbles in asset markets. By taking this approach, China’s adjustment will occur through high inflation, the highest one among all major economies in Figure 4.4, and appreciation of the real exchange rate. Countries may attempt to avert some of these consequences by issuing domestic bonds to offset the balance of payments inflows. But this course also has disadvantages, for example, fiscal costs and a tendency to attract yet more capital inflows by pushing up local bond yields.

Figure 4.4 Relative consumer price indexes, 2010=100

Sources: OECD Main Economic Indicators (MEI) database.

Second is to pursue independent monetary policies that target their own inflation and activity levels, combined with relatively flexible exchange rates and open capital accounts, which a growing number of emerging economies have been moving toward in the aftermath of the financial crises of the late 1990s. Given rising inflation pressures, the appropriate monetary policy in many emerging markets at present would likely be to tighten, which will, however, attract even more capital inflows and further appreciate exchange rates. Sustained appreciation raises concerns about loss of export competitiveness and could lead to contentious structural adjustments in the real economy. So countries may also fear that large appreciations will undercut their long-term growth potential.4 A standard recommendation for countries in this position is to tighten fiscal policy (increasing the rate of taxation or cutting government spending) as a way of reducing upward pressure on local interest rates and the exchange rate.

Third is to combine an independent monetary policy with a fixed exchange rate by closing the capital account through capital controls. Such controls may sometimes be a useful temporary expedient, but they are not unproblematic, especially in the longer term.

Figure 4.5 lists some of the main types of capital controls and some evidence of their varying effectiveness. Foreign exchange taxes can be effective in reducing the volume of flows in the short term, and can alter the composition of flows toward longer-term maturities. Unremunerated reserve requirements also can be effective in lengthening the maturity structure of inflows, but their effectiveness diminishes over time. There is some evidence that prudential measures that include some form of capital control (such as a limit on bank external borrowing) may be effective in reducing the volume of capital inflows.

|

Types of capital controls |

Volume of inflows |

Composition of inflows |

|

Foreign exchange tax |

Can somewhat reduce the volume in the short term. |

Can alter the composition of inflows toward longer-term maturities. |

|

Unremunerated reserve requirements (URRs): Typically accompanied by other measures |

|

Have been effectively applied in reducing short-term inflows in overall inflows, but their effect diminishes overtime. |

|

Prudential measures with an element of capital control |

Some evidence that prudential type controls can be effective in reducing capital inflows. |

|

|

Administrative controls: These are sometimes used in conjunction with URRs |

Effectiveness depends largely on existence of other controls in the country. |

|

Figure 4.5 Effectiveness of capital control measures5

In practice, most emerging economies combine the three in varying proportions, achieving, for example, a certain degree of monetary autonomy combined with a “managed” flexible exchange rate.

It is interesting to observe two major emerging economies as points on this continuum. Brazil is an example of flexible exchange rates, independent monetary policy and high international financial integration, which is now experiencing a fluctuation in its exchange rate, and adding pressure to its competitiveness. In addition, a rising current account deficit is raising concerns about the risk of a future crisis. Under such circumstances, it is plausible for the policy makers to turn to a combination of exchange market intervention and capital flow controls to try to temper or smooth the pace of its currency appreciation. More importantly, Brazil may need to tighten fiscal policy to reduce incentives for capital inflows. Strengthening macroprudential and financial regulation as well as developing capital markets can help reduce the risk of a build-up in financial fragility and improve the efficiency of capital allocation, along with better safety nets to reduce the costs of transitional unemployment. Many of these reforms will take time to implement.

China, another member of BRIC, represents a different point with limited exchange rate flexibility, backed by heavy exchange market intervention, and some capital controls. China is experiencing the high inflation pressures in goods and asset markets predicted by the first approach offered by WTO. Chinese policy makers may understand and appreciate the potential macromanagement benefits of greater exchange rate flexibility and more monetary autonomy. But the macroeconomic management has become intertwined with deep structural imbalances—high investment relative to consumption, industry relative to services, and corporate profits relative to wages—each bolstered by vested interests and a complex political economy.

Authorities are concerned about the size and duration of transitional unemployment caused by a downsizing of the tradable goods and export sectors, which may become a threat to the social stability ranking high on their priority list. Thus the move toward macroeconomic policy reform and more exchange rate flexibility in China, though inevitable, is likely to be prolonged (Brahmbhatt, Canuto, and Ghosh December, 2010).

To echo what Lamy said at the WTO seminar, reform of the international monetary system to cease currency war and put capital flow under control takes time. Joint efforts, from advanced and from emerging economies, are needed in global platforms such as the G-20 and the World Bank to coordinate advanced countries macroprudential and financial sector regulatory reform that can help reduce the risk and improve the quality of capital flows to emerging markets. Such process would not necessarily lead to radical accomplishment, but rather incremental action, backed by sound commitment to momentous progress over the medium term.

Inflation Targeting

Inflation, a rise in the overall level of prices, erodes savings, lowers purchasing power, discourages investment, inhibits growth, fuels capital outflow, and, in extreme cases, provokes social and political unrest. People view it negatively and governments consequently have tried to battle inflation by adopting conservative and sustainable fiscal and monetary policies.

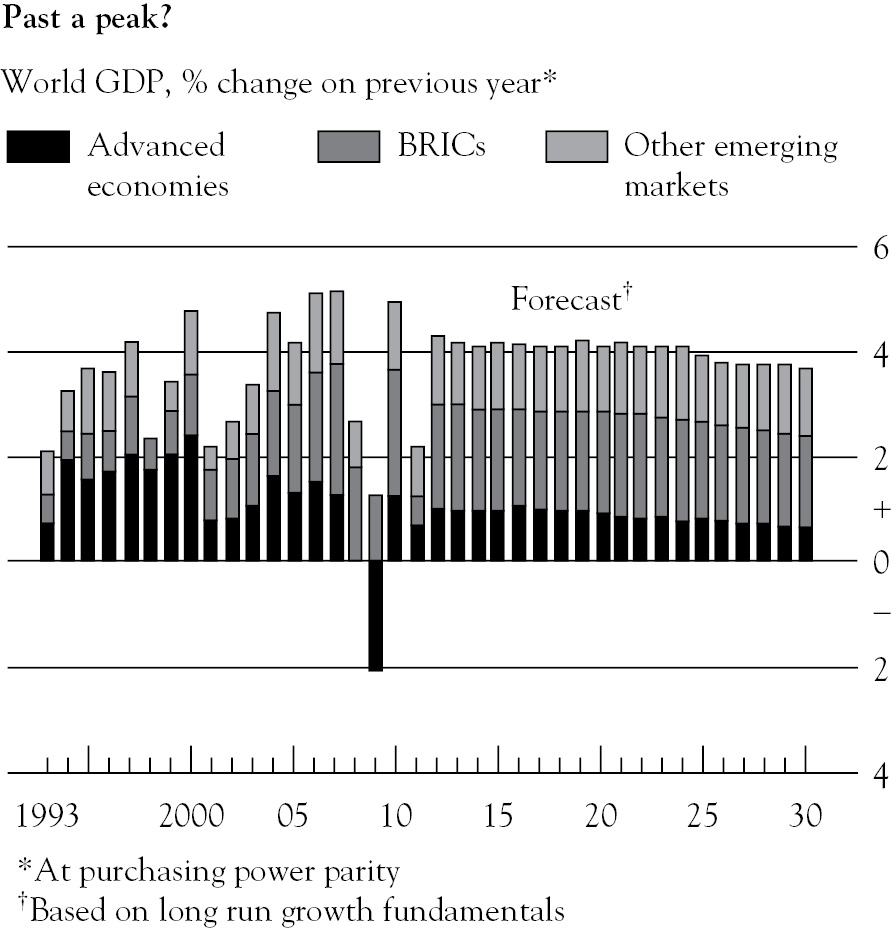

Because interest rates and inflation rates tend to move in opposite directions, central bankers have adopted inflation targeting to control the general rise in the price level based on such understanding of the links from the monetary policy instruments of interest rates to inflation. By applying inflation targeting a central bank estimates and makes public a projected or “target” inflation rate and then attempts to use interest rate changes to steer actual inflation toward that target. Through such “transmission mechanism,” the likely actions a central bank will take to rise or lower interest rates become more transparent, which leads to an increase in economic stability.

Inflation targeting, as a monetary-policy strategy, was introduced in New Zealand in 1990. It has been very successful in stabilizing both inflation and the real economy. As of 2010, as shown in Figure 4.6, it has been adopted by almost 30 advanced and emerging economies.6

Figure 4.6 Summary of Central Banks using inflation targeting to control inflation

Sources: Hammond 2011, Roger 2010, and IMF staff calculations.

Inflation targeting is characterized by (1) an announced numerical inflation target, (2) an implementation of monetary policy that gives a major role to an inflation forecast and has been called forecast targeting, and (3) a high degree of transparency and accountability.

A major advantage of inflation targeting is that it combines elements of both “rules” and “discretion” in monetary policy. This “constrained discretion” framework combines two distinct elements: a precise numerical target for inflation in the medium term and a response to economic shocks in the short term.7

Inflation Targeting With Advanced Economies

There are a number of central banks in more advanced economies—including the ECB, the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed), the BOJ, and the Swiss National Bank—that have adopted many of the main elements of inflation targeting. Several others are moving toward it. Although these central banks are committed to achieving low inflation, they do not announce explicit numerical targets or have other objectives, such as promoting maximum employment and moderate long-term interest rates, in addition to stablizing prices.

In popular perception, and in their own minds, central bankers were satisfied with inflation targeting as an effective tool to squeeze high inflation out of their economies. Their credibility is based on keeping inflation down and therefore they always must be on guard in case prices start to soar.

This view is dangerously outdated after the financial recession. The biggest challenge facing the advanced economies’ central banks today is that inflation is too low! After rebounding during the first two years of the recovery, due to United States quantitative easing and loosening monetary policy of other advanced economies, inflation in developed markets has drifted lower since mid-2011 and generally stands below central bank targets, as depicted in Figure 4.7. Given considerable slack in developed economies, however, inflation may drop further.

Figure 4.7 CPI Inflation of United States eurozone, and Japan from January 2000 to November 2013 (percent, year-on-year)

Sources: Bloomberg and QNB Group.

The most obvious danger of such low inflation is the risk of slipping into outright deflation, in which prices persistently fall. As Japan’s experience in the past two decades shows, deflation is both deeply damaging and hard to escape in weak economies with high debts. Since loans are fixed in nominal terms, falling wages and prices increase the burden of paying them. Once people expect prices to keep falling, they put off buying things, weakening the economy further.8

This is particularly severe in the eurozone, where growth averaged −0.7 percent in the first three quarters of 2013 and annual CPI inflation fell from 2.2 percent at the end of 2012 to 0.9 percent in the year to November 2013 (see Figure 4.7). At the same time the euro has appreciated 8.2 percent in 2013 against a weighted basket of currencies, which is likely to be holding back inflation and growth. The ECB already cut its main policy rate from 0.5 percent to 0.25 percent in November 2013, leaving little room for further interest rate cuts.

Meanwhile, inflation in the United States has fallen to around one percent, the lowest levels since 2009 when the global recession and collapsing commodity markets dragged down prices. These low inflation rates raise the risk that the United States together with the eurozone could be entering their own deflation trap with lost decades of low growth and deflation ahead.

Interestingly enough, Japan sets a deviant example in inflation targeting, in which its central bank wants to reversely boost inflation to a set target of two percent. Since the 1990s, the Japanese economy has languished in a weak state of feeble growth and deflation that has persisted into this century. From 2000 to May 2013, annual inflation of the CPI was negative (averaging −0.3 percent), while real GDP growth was less than one percent over the same period.

The Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who came to power at the end of 2012, introduced a raft of expansionary economic policies known as “Abenomics” (see Chapter 3), which included a two percent inflation target and buying about ¥13 trillion in financial assets (some ¥2 trillion in government bonds) every month as long as necessary. Together with heavy spending on public infrastructure and an active policy the Japanese yen was weakened.

Japan’s economy has turned. Growth has averaged 3.1 percent so far in 2013 and inflation rose from −0.3 percent in the year in May to 1.1 percent in the year in October. This puts it above inflation in both the United States and eurozone for the first time this century. Rising Japanese inflation is a direct consequence of expansionary economic policies introduced in 2013, which could help the country escape from the lost decades of low growth and deflation from the real estate crash of 1989 until today. Abenomics including a surge of inflation is likely to have contributed significantly to Japan’s improving economic performance.

The current situation in United States and eurozone calls for a continuation and possibly acceleration of unconventional monetary policy to offset the dangers that deflation could pose on an already weak recovery. The experience of Japan provides a useful historical precedent. It is likely that the ECB will engage in unconventional monetary policies to provide stimulus by extending its long-term refinancing operations (LTROs), which provide unlimited liquidity to EU banks in exchange for collateral at low interest rates. The ECB must also stress that its target is an inflation rate close to two percent for the eurozone as a whole, even if that means higher inflation in Germany.

The United States is still buying $55 billion worth of bonds a month after its recent cut of $10 billion per month in April 2014, and will maintain its current policy rate at essentially zero for “a considerable time after the asset purchase program ends.” If inflation continues to slow, QE tapering could take even longer to be implemented. Meanwhile, the Fed also can change its forward guidance as it just did to reduce the “threshold” below which unemployment must fall even further from 6.5 percent to 6 percent or below before interest rates are raised.9

Inflation Targeting With Emerging Economies

In emerging markets the inflation picture looks quite different. With unemployment rates hovering around long-term averages, these economies appear to be operating near their full potential. Correspondingly, emerging-markets consumer price inflation has been low since 2012 and has edged higher in recent months. In the aggregate, consumer price weighted emerging markets inflation ticked up to 4.2 percent year-over-year in September 2013, compared with 4.1 percent in August and 4 percent at the end of 2012 (see Figure 4.8). The sequential trend inflation rate (three months over three months, seasonally-adjusted annual rate) has risen more sharply since midyear, reaching 5.5 percent in September 2013.10

Figure 4.8 Emerging markets consumer price (percent)

Sources: J.P. Morgan Asset Management, data through September 2013.

The concern for emerging-market economies is high inflation together with potential slower growth. Inflation has started to pick-up in emerging markets during 2013, even as growth has fallen short of expectations. Growth looks particularly disappointing when compared with figures from before the 2008 financial crisis. A poorer growth-inflation trade-off suggests that economic potential in emerging markets has slowed considerably. This observation is a particular worry in the largest emerging markets, including China, India, and Brazil. All have been growing at poor rates compared with previous years, but inflation hasn’t fallen significantly during the past year.

Inflation targeting has been successfully practiced in a growing number of countries over the past 20 years, and many more countries are moving toward this framework. Although inflation targeting has proven to be a flexible framework that has been resilient in changing circumstances including during the recent global financial crisis, emerging markets must assess their economies to determine whether inflation targeting is appropriate for them or if it can be tailored to suit their needs. Facing the unique challenge of high inflation with slow growth, emerging economies may include currency rate and other alternatives, along with interest rates, to play a more pivotal role in stabilizing inflation.

State Capitalism

The spread of a new sort of state capitalism in the emerging world is causing increasing attention and problems. As a symbol of state owned enterprises (SOEs), over the past two decades, striking corporate headquarters have transformed the great cities of the emerging markets. China Central Television’s building resembles a giant alien marching across Beijing’s skyline; the gleaming office of VTB, a banking powerhouse, sits at the heart of Moscow’s new financial district; the 88-story PETRONAS Towers, home to Malaysia’s oil company, soars above Kuala Lumpur. These are all monuments to the rise of a new kind of Hybrid Corporation, backed by the state but behaving like a private-sector multinational.11

State capitalism is described usually as an economic system in which commercial and economic activity is undertaken by the state, with management and organization of the means of production in a capitalist manner including the system of wage labor, and centralized management.12

State capitalism also can refer to an economic system where the means of production are owned privately but the state has considerable control over the allocation of credit and investment, as in the case of France during the period of dirigisme. Alternatively, state capitalism may be used similar to state monopoly capitalism to describe a system where the state intervenes in the economy to protect and advance the interests of large-scale businesses. This practice is often claimed to be in contrast with the ideals of both socialism and laissez-faire capitalism.13 In 2008, the term was used by U.S. National Intelligence Council in “Global Trends 2025: A World Transformed” to describe the development of Russia, India, and China.

Marxist literature defines state capitalism as a social system combining capitalism, in which a wage system of producing and appropriating surplus value, with ownership or control by a state. Through such combination, a state capitalist country is one where the government controls the economy and essentially acts like a single huge corporation, extracting the surplus value from the workforce in order to invest it in further production.

State-directed capitalism is not a new idea. It’s remote roots can be traced back to the East India Company. After Russia’s October Revolution in 1917, using Vladimir Lenin’s idea that Czarism was taking a “Prussian path” to capitalism, Nikolai Bukharin identified a new stage in the development of capitalism, in which all sectors of national production and all important social institutions had become managed by the state. He officially named this new stage as “state capitalism.”14

Rising powers have always used the state to drive the initial growth, for example, Japan and South Korea in the 1950s, or Germany in the 1870s, or even the United States after the war of independence. But these countries have eventually found the limits of such a system and thus moved away from it.

Singapore’s economic model, under Lee Kuan Yew’s government, is another form of state capitalism, where the state lets in foreign firms and embraces Western management ideas while owning controlling shares in government-linked companies and directs investments through sovereign wealth funds, mainly Temasek.

Within the EU, state capitalism refers to a system where high coordination between the state, large companies and labor unions ensure economic growth and development in a quasicorporatist model. Vivien Schmidt cites France and, to a lesser extent, Italy as prime examples of modern European State capitalism.15

The leading practitioners of state capitalism nowadays are among emerging markets represented by China and Russia—after Boris Yeltsin’s reform. The tight connection between its government and business is so obvious, whether in major industries or major markets. The world’s ten biggest oil-and-gas firms, measured by reserves, are all state-owned. State-backed companies account for 80 percent of the value of China’s stock market and 62 percent of Russia’s. Meanwhile, Brazil has pioneered the use of the state as a minority shareholder together with indirect government ownership through the Brazilian National Development Bank (BNDES) and its investment subsidiary (BNDESPar).16

State capitalists like to use China’s recent successes against the United States and EU’s troubles in the financial crises. They argue that state owned enterprises have the best of both worlds: the ability to plan for the future, but also respond to fast-changing consumer tastes. State capitalism has been successful at producing national champions that can compete globally. Two-thirds of emerging-market companies that made it onto the Fortune 500 list are state-owned, and most of the rest enjoy state support of one sort or another. Chinese companies are building roads and railways in Africa, power plants and bridges in South-East Asia, and schools and bridges in the United States. In the most recent list of the world’s biggest global contractors, compiled by an industry newsletter, Chinese companies held four of the top five positions. China State Construction Engineering Corporation has undertaken more than 5,000 projects in about 100 different countries and earned $22.4 billion in revenues in 2009. China’s Sinohydro controls more than half the world’s market for building hydropower stations.17

In 2009, just two Chinese state-owned companies, namely China Mobile and China National Petroleum Corporation, made more profits ($33 billion) than China’s 500 most profitable private companies combined. In 2010, the top 129 Chinese SOEs made estimated net profits of $151 billion, 50 percent more than the year before (in many cases helped by near-monopolies). In the first six months of 2010, China’s four biggest state commercial banks made average profits of $211 million a day.

Under state capitalism, governments can provide SOEs and companies under their indirect control with the resources that they need to reach global markets. One way is by listing them on foreign exchanges, which introduces them to the world’s sharpest bankers and analysts. Meanwhile, they can also acquire foreign companies with rare expertise that produces global giants. Shanghai Electric Group enhanced its engineering knowledge by buying Goss International for $1.5 billion and forming joint ventures with Siemens and Mitsubishi. China’s Geely International gained access to some of the world’s most advanced car-making skills through its acquisition of Volvo for $1.8 billion.‡

Governments embrace state capitalism because it serves political as well as economic purposes. Especially, during the recent recession, it puts vast financial resources within the control of state officials, allowing them access to cash that helps safeguard their domestic political capital and, in many cases, increases their leverage on the international stage.

Risks Associate With State Capitalism

Dizzied by the strength of state capitalism demonstrated through the recent financial crisis, it is easy for outside investors to become blind to the risks posed by the excessive power of the state. Companies are ultimately responsible not to their private shareholders but to the government, which not only owns the majority of the shares but also controls the regulatory and legal system. Such inequality creates a lot of risks for investors.

There is striking evidence that state-owned companies are less productive than their private competitors. An OECD paper in 2005 noted that the total factor productivity of private companies is twice that of state companies. A study by the McKinsey Global Institute in the same year found that companies in which the state holds a minority stake are 70 percent more productive than wholly state-owned ones.

Studies also show that SOEs use capital less efficiently than private ones, and grow more slowly. The Beijing-based Unirule Institute of Economics argues that, allowing for all the hidden subsidies such as free land, the average real return on equity for state-owned companies between 2001 and 2009 was −1.47 percent.§ SOEs typically have poorer cost controls than regular companies. When the government favors SOEs, the others suffer. State giants soak up capital and talent that might have been used more efficiently by private companies.

SOEs also suffer from “principal-agent problem,” which indicates the tendency of managers, as agents who run companies, to put their own interests prior to the interests of the owners who are the principals. This problem is getting more severe under state capitalism. Politicians who can control or influence the nomination of SOE executives may have their own agenda while being too distracted by other things to exercise proper oversight. Boards are weak, disorganized, and full of insiders.

For example, the Chinese party state exercises power through two institutions: the State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) and the Communist Party’s Organization Department. They appoint all the senior managers in China Inc. Therefore, even the most prestigious top executives of China’s SOEs are cadres first and company men second, who naturally care more about pleasing their party bosses than about the market and customers. Ironically, China’s SOEs even have successfully attempted to make them pay more dividends to their major shareholder, that is, the state.

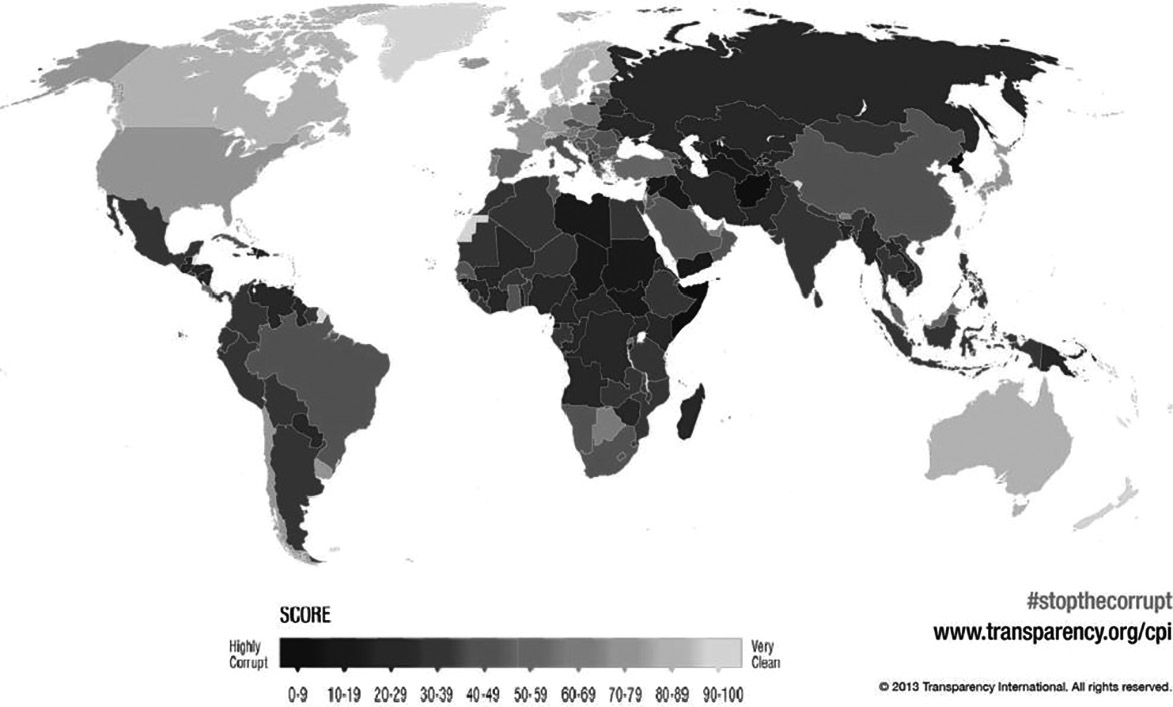

Politicians under state capitalism have far more power than they do under liberal capitalism, which creates opportunities for rent seeking and corruption on the part of the SOE elite. State capitalism suffers from the misfortune that it has taken root in countries with problematic states. It often reinforces corruption because it increases the size and range of prizes for the victors. The ruling parties of SOEs have not only the government apparatus but also huge corporate resources at their disposal.

In China, where its long history combines with a culture of guanxi (relationships) and corruption, the PBOC, China’s central bank, estimates that between the mid-1990s and 2008, some 16,000 to 18,000 Chinese officials and SOE executives made off with a total of $123 billion. Russia has the nepotism and corruption among a group of “bureaugarchs,” often-former KGB officials, who dominate both the Kremlin and business. Other BRIC countries suffer from the similar problems. Transparency International, a campaigning group, ranks Brazil 72nd in its corruption index for 2013, with China 80th, India 94th, and Russia an appalling 127th. In contrast, as Figure 4.9 shows, advance economies favoring a free market model score much better than their emerging market counterparts under state capitalism.

Figure 4.9 Corruption Perceptions Index 2013

Source: Transparency International Transparency International¶

State capitalism also stems the rise of various degrees of globalization as it shackles the flow of money, goods, ideas, information, people, and services within countries and across international borders. Ensuring that trade is fair is harder when some companies enjoy the direct or indirect support from a national government. Western politicians are beginning to lose patience with state-capitalist powers that rig the system in favor of their own companies.

More worrying is the potential for capriciousness. State-capitalist governments can be unpredictable with scant regard for other shareholders. Politicians can suddenly step in and replace the senior management or order SOEs to pursue social rather than business goals. In 2004, China’s SASAC and the Communist Party’s Organization Department rotated the executives of the three biggest telecoms companies. In 2009, they reshuffled the bosses of the three leading airlines. In 2010, they did the same to the heads of the three largest state oil companies, each of which is a Fortune 500 company.

Response to State Capitalism

Will state capitalism completely reverse globalization’s progress? Ian Bremmer, the founder and president of the Eurasia Group, indicated that it is highly unlikely. Despite the relatively high growth of emerging markets after the global financial crisis, it has not proven that government engineered growth can outstrip the expansion of well-regulated free markets over the long run. States like China and Russia will face tremendous pressures as internal issues contradict their development. Recently, we witnessed the terrible environmental price China continues to pay for its growth. And Russia’s vulnerable reliance on Vladimir Putin, at the expense of credible governing institutions, put their economic resilience to the test. A free market does not depend on the wisdom of political officials for its dynamism; that’s the primary reason it will almost certainly withstand the state capitalist challenge.

However, the financial crisis and advanced countries’ apparent responsibility for it may ensure the growth of state capitalism over the next several years. The future of this path will depend on a range of factors, including any wavering of Western faith in the power of free markets, the U.S. administration’s capacity to kick-start its economy growth, the ability of Russian government’s dependence on oil exports to withstand the pain inflicted by prices drop, the Chinese Communist Party’s ability to create jobs and maintain tight control of its own people, and dozens of other variables. In the meantime, corporate leaders and investors must recognize that free market capitalism is no longer the unchallenged international economic paradigm and that politics will have a profound impact on the performance of markets for many years to come.

Increasingly, multinational companies and international traders are operating in an environment where they have to pay much more attention to politics, and they can’t invest purely on the basis of where the markets may be attractive.18

Economic Nationalism

In the good old days, growth in trade and cross-border investment brought prosperity and development. Globalization appeared to deliver rising living standards for all and there was no conflict. Leaders of nations could simultaneously support the architecture of globalization while taking the plaudits for prosperity at home. That’s all changed. As English statesman Lord Palmerston noted: “nations have no permanent friends or allies, they only have permanent interests.”

Nations led by politicians, who are primarily interested in strengthening their political capitals by serving and protecting their most powerful constituents (the local voters, political benefactors, or powerful industries and interest parties), naturally try to help boost their domestic economies rather than making choices with the global economy in mind. In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, these interests dictated a body of policies that emphasized domestic control of the economy, labor, and capital formation, even if this required the reversal of the trend to greater global integration and a return to economic nationalism.19

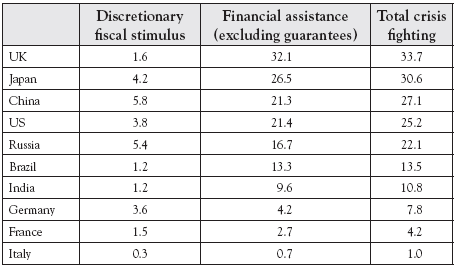

The financial crisis inevitably revealed that integration reduces the effectiveness of a nation’s economic policies, unless other nations take coordinated action. Governments’ initial reaction to the global financial crisis was to pour large amounts of government spending in a competitive rather than cooperative way to bailout its own economy first, as shown in Figure 4.10.

Figure 4.10 2009–2010 fiscal stimulus and financial bailouts, percentage GDP (Select G-20 countries)

Source: IMF, 2009b.

As it became clear that the recession would last longer than originally anticipated, governments started to throw up barriers to trade and investment meant to keep local workers employed through the next election. Economic nationalism leads to the imposition of tariffs and other restrictions on the movement of labor, goods, and capital. The United States tacked a 127 percent tariff on to Chinese paper clips; Japan put a 778 percent tariff on rice. Protection is worse in the emerging world, as shown in Figure 4.11. Brazil’s tariffs are, on average, four times higher than the United States, and China is three times higher.

Figure 4.11 2012 Year of MFN applied tariff

Source: © World Trade Organization 2013.

Besides tariffs, big emerging markets like Brazil, Russia, India, and China have displayed a more interventionist approach to globalization that relies on industrial policy and government-directed lending to give domestic sellers more advantages. Industrial policy enjoys more respectability than tariffs and quotas, but it raises costs for consumers and puts more efficient foreign firms at a disadvantage. The Peterson Institute estimates local-content requirements cost the world $93 billion in lost trade in 2010.20

For advanced economies, government procurement policies also favor national suppliers. “Buy American” campaigns as seen in the recent U.S. presidential election and preferential policies are used to direct demand. Safety and environmental standards are used to prevent foreign products penetrating national markets. According to Global Trade Alert, a monitoring service, at least 400 new protectionist measures have been put in place each year since 2009, and the trend is on the increase.

Another obvious move in economic nationalism is through capital markets. Nations facing financial difficulties with high levels of government debt seek to limit capital outflows. These would prevent depositors and investors withdrawing funds to avoid potential losses from sovereign defaults. In Europe, there was a tendency for a breakdown in the common currency and redenomination of investments into a domestic currency.

In Cyprus, explicit capital controls designed to prevent capital flight were implemented. On the other hand, low interest rates and weak currencies in developed economies have led to volatile and destabilizing capital inflows into emerging nations with higher rates and stronger growth prospects. Brazil, South Korea, and Switzerland have implemented controls on capital inflows.

As a result, global capital flows fell from $11 trillion in 2007 to a third of that in 2012. The decline happened partly for cyclical reasons, but also because regulators of nations who saw banks’ foreign adventures end in disaster have sought to gate their financial systems.

Political tension and national security can make existing economic nationalism more complicated and intensified. Mr. Snowden first revealed the existence of the clandestine data mining program of U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) in June 2013. The NSA involves U.S. firms in the IT and telecoms space. Basically, it ensures U.S. firms operate under certain kinds of rules in connection with the U.S. government and the military industrial complex. Snowden’s revelations provoked a storm in the Chinese media and added urgency to Beijing’s efforts to use its market power to create indigenous software and hardware.

As a consequence, U.S. technology companies including Cisco Systems immediately face new challenges in selling their goods and services in China as fallout from the U.S. spying scandal, which caused relations between Beijing and Washington to be strained by Mr. Snowden’s reports of American espionage, starts to take a toll. Cisco Systems warned its revenue would dive as much as 10 percent in the fourth quarter of 2013, and keep dipping until after the middle of 2014, in part due to a backlash in China after Snowden’s revelations about U.S. government surveillance programs. Beijing may be targeting Cisco in particular as retaliation for Washington’s refusal to buy goods from China’s Huawei Technologies Co, a telecommunications equipment maker that the United States claims is a threat to national security because of links to the Chinese military.

Response to Economic Nationalism

Economic nationalism may offer near-term pain relief but, as a political response to economic failure, it only risks locking in that economic failure for the long term. The world learned from the Great Depression that protectionism makes a bad situation worse.

Trade encourages specialization, which brings prosperity. Economic cooperation encourages confidence and enhances security. Global capital markets, for all their problems, allocate money more efficiently than local ones.

In December 2013, the WTO sealed its first global trade deal after almost 160 ministers gathered on the Indonesian island of Bali and agreed to reforms to boost world commerce. Tense negotiations followed 20 years of bitter disputes. At the heart of the agreement were measures to ease barriers to trade by reducing import duties, simplifying customs procedures, and making those procedures more transparent to end years of corruption at ports and border controls.

“For the first time in our history, the WTO has truly delivered,” WTO chief Roberto Azevedo told exhausted ministers after the long talks. “This time the entire membership came together. We have put the ‘world’ back in World Trade organization,” he said. “We’re back in business … Bali is just the beginning.”

China, a key member of BRICS, also started to respond to the challenge in the right way. On December 2nd of 2013, the PBOC issued a set of guidelines on how financial reform will proceed inside the new Shanghai Free Trade Zone (SFTZ). This 29 sq. km (about 18 sq. miles) enclave, created three months earlier, has been trumpeted by Li Keqiang, the country’s prime minister, as a driver of economic reform under his new administration.

To boost cross-border investment and trade, the PBOC wants to allow firms and individuals to open special accounts that will enable them to trade freely with foreign accounts in any currency. Selected foreign institutional investors may be allowed to invest directly in the Shanghai stock market. Interest rates may be liberalized for certain accounts at designated firms inside the SFTZ, which would open a new window of globalization and free capital market in China.

Conclusion

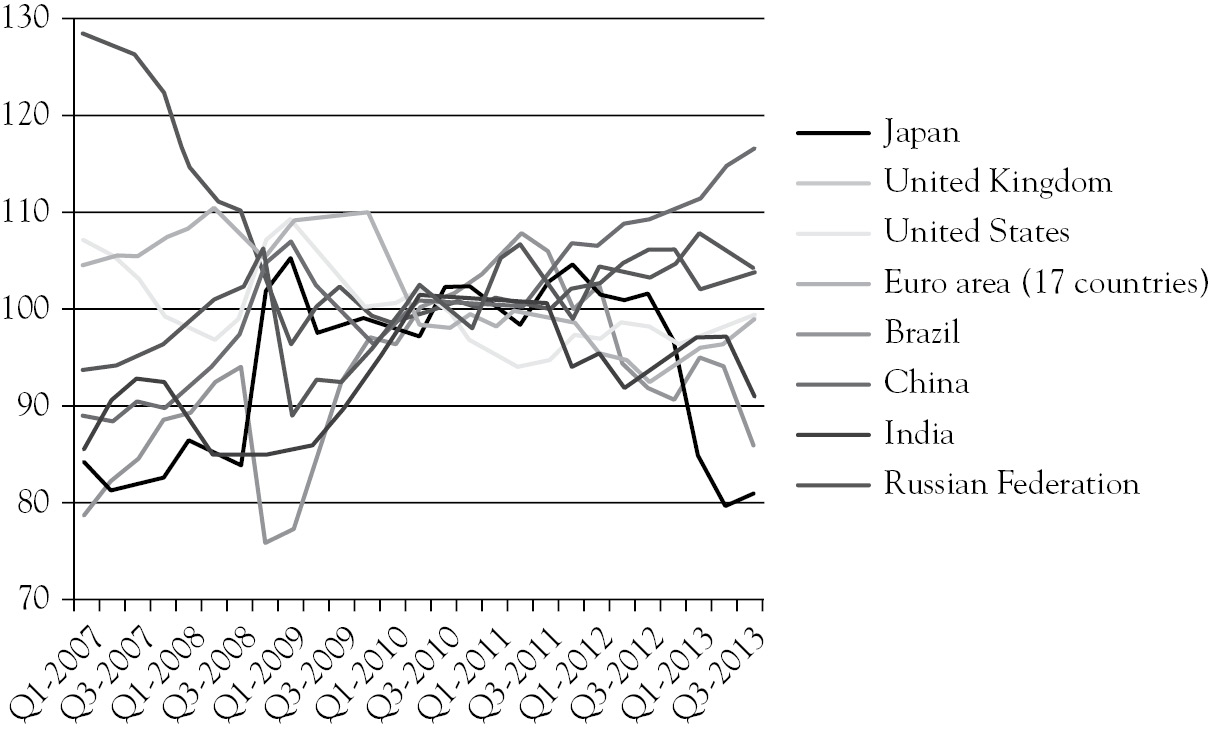

As mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, the BRIC economies are contributing less to global growth. In 2008 they accounted for two-thirds of world GDP growth. In 2011 they accounted for half of it, in 2012 a bit less than that. The IMF sees growth staying at about that level for the next five years. Goldman Sachs predicts that, based on an analysis of fundamentals, the BRICs share will decline further over the long term.

Other emerging markets will pick up some of the slack including the “Next 11” which includes Bangladesh, Indonesia, Mexico, Nigeria, and Turkey, to name a few. Although there are various reasons to think that this N-11 cannot have an impact on the same scale as that of the BRICs, emerging markets other than BRIC will play a vital role in the future. Advanced economies will continue to lose their share which will contribute to a general easing of the pace of world growth,21 as shown in Figure 4.12.

Figure 4.12 Emerging markets led by BRIC have demonstrated stronger growth than the advanced economies

Source: Goldman Sachs.

Internationally, lower growth could focus leaders on increased cooperation and a new push for liberalization, which will mitigate the risks, as discussed, of currency war, inflation targeting, state capitalism, and economic nationalism. A predicted slowdown could bring new consensus to global trade talks as witnessed in Bali in December 2013. More deals that address nontariff trade barriers, and especially those on trade in services, could yield bigger benefits down the road.

* Ibidem.

† China replaced the United States to become the world’s largest merchandise trader in 2013. Data from the U.S. Commerce Department showed on Feb 6, 2014 that the United States’ combined exports and imports stood at $3.91 trillion in 2013, about $250 billion less than China’s.

‡ Ibidem.

§ Ibidem.

¶ More detail information available at http://cpi.transparency.org/cpi2013/results/