CHAPTER 7

Organizing a Project Team

This chapter covers the following topics:

• Assessing internal skills

• Serving as a project coordinator

• Working with a project scheduler

• Managing team issues

• Defining agile roles and responsibilities

• Hosting agile project ceremonies

• Hiring a team

Think of your favorite caper movie. Remember how the heist team in the movie is assembled? Each member has a specialty and other necessary skills to get the job done. Notice how there’s never an extra character walking around slurping coffee, dodging work, and whining about how tough their job is? Unfortunately, in the world of IT project management, you’ll have to work with both types of characters—the specialists and the extras.

As a project manager, you will recruit the diehard dedicated workers who are genuinely interested in the success of the project. These team members are exciting to be around, because they love to learn, love technology, and work hard for the team and the success of the project. The other type of team members you’ll encounter are nothing less than a pain in the, er, neck. These folks couldn’t care less about the project, the success of the organization, or anyone else on the team. Their goal is to complete their required hours, draw a paycheck, and get on with their lives.

The reality is, however, most people want to do a good job. Most team members are generally interested in the success of the project. If you get stuck with one of the rotten apples, there are methods to work with them—and around them. This chapter will focus on how you, the project manager, can assemble a team that works well together. Your team may not be in any caper movies, but parts of the project can be just as exciting.

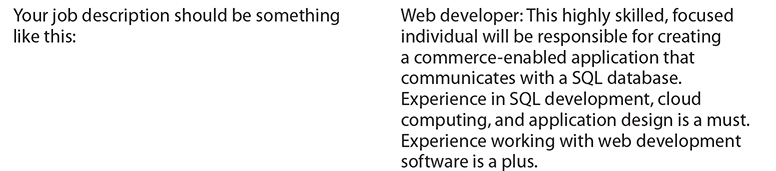

Assessing Internal Skills

Whether you get to handpick your project team or your team is assigned to you by management, you will still need to get a grasp on the experience levels of each team member. If you have an understanding of what your team members are capable of doing, the process of assigning tasks and creating the project plan will go much easier for you.

As a project manager, you must create a method to ascertain the skills of your team. It would, no doubt, be disastrous to your project if you assembled a team only to learn later that they were not qualified to do the work assigned to them. In some cases, this task will be easier to do than in others, especially if you’ve worked with the team members before, interviewed the team members, or completed a skills assessment worksheet.

Identifying Resource Requirements

Before you can start building your project team, you need to know what resources you’ll need for the project to be successful. Recall that resources are materials, facilities, tools, equipment, and, especially in this chapter, people. Projects are completed by people, and you’ll need the right people to do the right work to complete the project objectives. Depending on the nature of the project, you’ll probably have a good idea what the project needs in order to be successful. You can, and should, use the project’s scope baseline to help you and the project team identify the types of resources that you need on your project.

By referencing the scope baseline, and in particular the WBS or product backlog, you can identify the resources you’ll need to complete the work packages within the project. By mapping the resources to the WBS or product backlog, you can create a resource breakdown structure. A resource breakdown structure illustrates what resources are needed to create corresponding deliverables. This can also help when you assign resources to project activities—there may be only so many resources available, so you’ll need to create a project schedule that considers the availability of the project resources to create the identified project deliverables.

This examination of resource requirements can also help you discover a resource shortage. When reviewing the work, the interproject dependencies, and the calendars of the available resources, you may discover that you don’t have the needed resources to complete the work as planned. Now you’ll have to either reschedule the project work, acquire resources to alleviate the resource shortage, or even change your project plan based on the lack of resources available to complete the project.

Avoiding resource shortages, overallocation issues, and interproject contention is ideal, but it takes accurate mapping of who’s doing what in the organization, and actual reporting of time spent on assignments. When you consider all the moving pieces within a project and within an organization, it’s often a real challenge to avoid these issues and have the right resources you need when you need them. Communication, system-wide scheduling of resources, and reporting of issues or risks within projects that may affect resource scheduling are needed but not always easy to achieve or maintain.

Experience Is the Best Barometer

As you gain experience as a project manager, you will learn which people you’d like on your team—and which you wouldn’t. Your first requirement for team members is the competency of the individuals to complete the work, but a close second is their attitude, willingness to work, and how well they can get along and work with others. If you are a consultant brought into the mix to manage an IT implementation, you’ll have to learn about the team members, their goals, and their abilities.

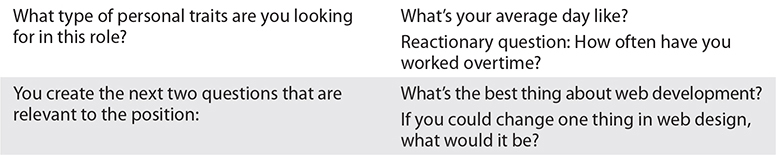

You must use strategies to recruit and woo knowledgeable and hard-working team members onto your team. This means, of course, you’ll have to do fact-finding missions to gain information on your recruits. As Figure 7-1 demonstrates, you have available to you many methods to assess internal skills—this is your resource pool.

Figure 7-1 Assessing the internal resource pool can help with resource identification.

Once you’ve started your fact-finding mission, rely on multiple methods to assess internal skills:

• Prior projects Obviously, if you’ve worked with your team members prior to this project, you’ll have a good idea who’s capable of what tasks. You’ll also have a record, through historical information, of who’s reliable, dependable, and thorough, and who has other traits of a good worker.

• Organizational knowledge You may not have worked directly with particular team members who have been assigned to your project, but you might have a good idea of their track record. Let’s face the facts: in your organization, it’s likely that there are people you haven’t worked with, but you know the type of workers they are by their reputation, their ability to accomplish tasks, and what others say about them. Gossip is one thing, but proven success (or failure) is another. The best way to learn about someone, of course, is not through hearsay, but to work with them or speak directly with their manager or other project managers.

• Recommendation of management You may not have the luxury of selecting your team members like you’re picking a kickball team at recess. You’ll probably be able to recruit some members of your team, but not all of them. Functional or senior management will have an inside track on the abilities of employees and can, and will, recommend members for your project. Management will also be able to select individuals who can commit time to the project.

• Recommendation of team members Most likely, you will have other IT professionals within your organization whom you trust and confide in. These folks can help you by recommending other winners for your team. These individuals are likely in the trenches working side-by-side with other IT pros. Use their “scouting” to find excellent members to work on your project.

Résumés and Skill Assessments

Another source, if you have access to the document, is the résumé for each team member. A résumé can quickly sum up the skill set of a team member. You may want the project team to create quick résumés for you in order to learn about the experiences of individual members. Use caution with this approach, however. Résumé submission has the connotation of getting, or keeping, a job, and your team members may panic. If you want to use this method but are uneasy using the word “résumé,” have the team members create a listing of the projects, their skills, and other past accomplishments. This will give you a way to quickly understand the collection of talent and then assign work to the team.

You might also rely on websites such as LinkedIn, where your colleagues have posted their résumés, skill sets, and credentials. Of course, use that approach with caution, because the individuals may have bloated their experience or not updated their credentials in some time. (And as I’m writing this, I’m assuming for future readers that LinkedIn still exists as I know it today.)

A collection of skills will also allow you to determine if you have the resources to complete the project. For example, if you’re about to create a database that will span 18 states with multiple servers that will provide real-time transactions for clients, it’ll be tough to do if none of your team members has worked with relational databases before.

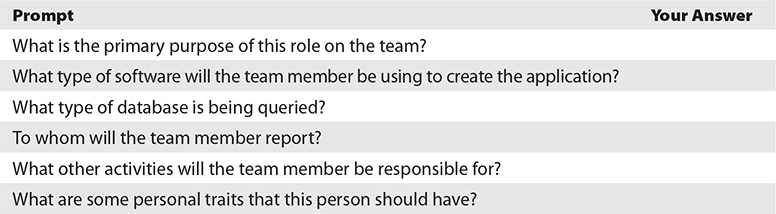

Create a Roles and Responsibilities Matrix

A roles and responsibilities matrix is a tool used to identify all of the roles within a project and the associated responsibilities to the project work. This matrix is an excellent way to identify the needed roles of the project participants, identify what actions they’ll need to take in the project, and ultimately determine if you have all of the roles to complete the identified responsibilities. Here’s a quick example of a matrix for a software rollout project.

Here’s the legend for this matrix:

A = Approves

R = Reviews

P = Participant

C = Creator

The roles and responsibilities matrix can help the project manager identify the needed resources to complete the project work—and determine if the resources exist within the organization’s resource pool. Later in the project, the project manager will use an even more precise matrix, the responsibility assignment matrix (RAM), to identify which tasks are assigned to which individuals. Another form of a responsibility assignment matrix is a RACI chart. A RACI chart is similar to the previous example matrix, but it uses the legend of Responsible, Accountable, Consult, and Inform. And that’s why it’s called a RACI chart—the first letter of each responsibility spells RACI.

Learning Is Hard Work

Within the IT employment world, a requirement for certification has become practically mandatory. Certifications such as the PMP, PMI-ACP, PRINCE2, AWS Credentials, Microsoft Certified Systems Engineer, and Oracle DBA—even industry certifications like CompTIA’s Project+, A+, and Network+—are proof of your knowledge in a particular area of technology.

Individuals can earn these certifications based on training, experience, or a combination of both. Certifications are certainly a way to demonstrate that professionals have worked with the technology, understand the major concepts, and were able to pass the exam. Certifications do not, however, make the individual a master of all technologies.

Within your team, whether members have certifications or not, you’ll need to assess if they need additional training to complete the project. Training is always seen as one of two things: an expense or an investment. Training is an expense if the experience does not increase the ability of the team to implement tasks. Training is an investment if the experience greatly increases the ability of the team to complete the project.

When searching for a training provider, consider these questions:

• What is the experience of the trainer?

• Can the trainer customize the class to your project?

• Would hiring a mentor be a better solution than classroom training?

• What materials are included with the class?

• What is the cost of the course?

• Is there an in-house training department that can deliver the training, provide assistance in developing the curriculum in-house, or assist in contracting with an outside trainer?

• Would it be more cost effective to host the training session in-house?

• Are there viable online solutions that can save time and provide value?

These questions will help you determine if training is right for your project team. In some instances, standard introductory courses are fine. Typically, the more customized the project, the more customized the class should be as well. Don’t assume that just because a training center is the biggest, it’s also the best. No matter how luxurious a training room, how delicious the cookies provided, or how slick the brochures are, the success of the class rests on the shoulders of the trainer. And online education platforms, such as Udemy (https://www.udemy.com), are becoming a quick way to ramp up on new technologies and approaches for the project team.

Creating a Team

You can’t approach creating a team the way you would approach baking a cake or completing a paint-by-number picture. As you deal with multiple individuals, you’ll discover their personalities, their ambitions, and their motivations. Being a project manager is as much about being a leader as it is about managing tasks, deadlines, and resources.

You will, through experience, learn how to recognize the leaders within the team. You’ll have to look for the members who are willing to go the extra mile, who do what it takes to do a job right, and who are willing to help others excel. These attributes signal the type of members you want on your team. The easiest way to create teams with this type of worker? Set the example yourself.

Imagine yourself as a team member on your project. How would you like the project manager to act? Or call upon your own experience: What have previous project managers taught you by their actions? By setting the example of how your team should work, you’re following ageless advice: leading by doing.

Defining Project Manager Power

Project managers have responsibility. And with that responsibility comes power. When it comes to the project team, you are seen as someone with some degree of power. Get used to it, but don’t let it go to your head. While the project manager must have some degree of power to get the project work done, the level of degree is also likely relevant to the organizational structure you’re working in. For example, recall that a functional organization gives the power to the functional manager, and the project manager may be known as just a project coordinator.

A project manager does, however, wield a certain amount of power in most organizations. The project team can see this power, correctly or incorrectly, based on their relationship with you. Their perception of your power—and how you use your project management power—will influence the project team and how they accomplish their project work.

There are five types of project manager powers:

• Expert The authority of the project manager comes from experience with the technology the project focuses on.

• Reward/penalty The project manager has the authority to give or withhold something of value to team members.

• Formal The project manager has been assigned by senior management and is in charge of the project. This is also known as positional power.

• Coercive The project manager has the authority to discipline the project team members. This is also known as penalty power. When the team is afraid of the project manager, it’s coercive.

• Referent The project team personally knows the project manager. Referent can also mean the project manager refers to the person who assigned them to the position—for example, “The CEO assigned me to this position, so we’ll do it this way.” This power can also mean the project team wants to work on the project or with the project manager because of the high priority and impact of the project.

Hello! My Name Is…

If your team works together on a regular basis, then chances are the team has already established camaraderie. The spirit of teamwork is not something that can be born overnight—or even in a matter of days. Camaraderie is created from experiences of the teammates. A team’s successful installation of software, or even a failure, creates a sense of unity among the team.

It’s mandatory on just about any project that team members work together. Here’s where things get tricky. Among those team members, you’ve got ambition, jealousies, secret agendas, uncertainties, and anxiety pooling in and seeping through the workers on your project. One of your first goals will be to establish some order in the team and change the members’ focus to the end result of the project. Personal ambitions are fine, but when they take precedence over the good of the project, they can have a detrimental effect on the success of a project.

By motivating your team to focus on the project deliverables, you can, like a magician, misdirect their attention from their own agendas to the project’s success. You can spark the creation of a true team by demonstrating how the members are all in this together. How can you do this? How can you motivate your team and change the focus from self-centric to project-centric? Here are some methods:

• Show the team members what’s in it for them. Remember the WIIFM principle—“What’s In It For Me.” Show your team members what they personally have to reap from the project. You may do this by telling them about monetary bonuses they’ll receive. Maybe your team will get extra vacation days or promotions. At the very least, they’ll be rewarded with adding this project to their list of accomplishments. Who knows? You’ll have to find some way to make this project more personally important for each team member.

• Show the team what this project means to the organization. By demonstrating the impact that this implementation has for the entire organization, you can position the importance of the success (or failure) of the project squarely on the team’s shoulders. This method gives the team a sense of ownership and a sense of responsibility.

• Show the team why this is exciting. IT project managers sometimes lose the sense of excitement wrapped up in technology. Show your team why this project is cool, exciting, and fun, and the implementation will hardly be like work. Remember, IT pros typically love technology—so let them have some fun! It is okay to have a good time and enjoy your work.

• Show the team members their importance. Team members need to know that their work is valued and appreciated. You can’t fake this stuff. Develop a sense of caring, a sense of pride, and tell your team members when they do a good job. Let them own the technology, use the technology, and be proud of their work.

Where Do You Live?

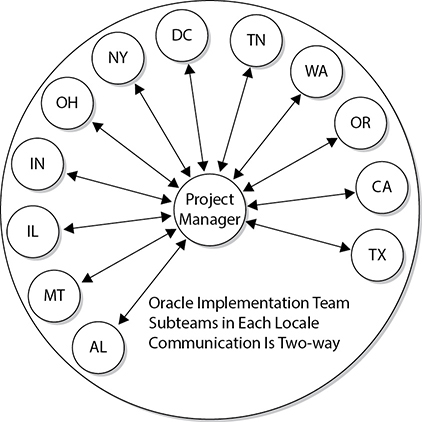

In today’s world, it’s typical of a single project to span the globe. No doubt it’s difficult for team members to feel like they are part of the same team when some team members are based in London and their counterparts are in Phoenix. Ideally, co-located teams communicate better, work together better, and have a stronger sense of ownership. Reality, however, proves that virtual teams exist in organizations, and the project manager must take extra measures to ensure that the project succeeds regardless of the geographical boundaries. When dealing with a virtual team, you will likely build your team around subteams. A subteam is simply a squadron of team members unique to one task within the project or within each geographical area.

For example, as depicted in Figure 7-2, a company is implementing Oracle servers throughout its enterprise. The company has 12 locations throughout the United States. Some of the same tasks that need to be accomplished in Ohio will also need to be performed in Texas.

Figure 7-2 Virtual teams and subteams demand more attention to communication than co-located teams.

Rather than having a six-member team fly around the globe to meet with other teams, the project manager implements 12 subteams, each with six members. Of the six members, one is the team leader for that location. The team members in each location report to their immediate team leader. All of the team leaders report to the project manager, the 73rd member of the team. Implementation of the Oracle servers at each location will follow a standard procedure for the installation and configuration. The path to success should be the same at each location regardless of geography.

Certainly, not all projects will map out this smoothly. Team members at some sites may not have the technical know-how of those at others, and travel will be required. In other instances, some sites will require more configuration than others, or an increase in security, or other variances. The lesson to be learned is that when teams are dispersed, a chain of command must be established to create uniformity and smooth implementation. Unfortunately, the phrase “out of sight, out of mind” often proves true when dealing with dispersed project teams.

Finally, when working with multiple subteams, communication is paramount. Team leaders and the project manager should have regularly scheduled meetings either in person or through teleconferences or videoconferences. In addition, team leaders should have the ability to contact other team members around the globe. You’ll need to plan for how to overcome communication challenges such as time zones, language barriers, and cultural differences.

In some instances, team members from different teams will need to work together as well. For example, if the communication between two servers has to be configured, the teammates responsible for this step of the configuration will need to coordinate their configurations and installation with the teammates who have identical responsibilities in other locations.

Building Relationships

When an individual joins your team, you and that individual have a relationship: project manager to team member. Immediately the team member knows their role in the project as a team member, and you know your role in relation to the team member as the project manager.

What may not be known, however, is the relationships between team members. You may need to introduce each team member and explain why that person is on the team and what responsibilities that person has. Don’t expect your team members to figure things out for themselves. In a large project, it would be ideal to have a directory of the team members, their contact information, and their arsenal of talents made available to the whole team.

On all projects, your team will have to work together very quickly. It’s not a bad idea to bring the team together in some type of activity away from the workplace. With virtual teams, it’s ideal to bring everyone into a central location for face-to-face meetings and team-building activities. The following are examples of team-building exercises:

• A bowling excursion

• A hike and overnight stay in the wilds, or some other outdoor activity

• A weekend resort meeting to learn about each other and discuss the project

• A trip to your local pool hall for an impromptu round of team pool

Serving as a Project Coordinator

If you’re fairly new to project management or you’re working in a functional organization, you may be given the role and title of project coordinator rather than project manager. The project coordinator is an individual who does just that: coordinates the project. This isn’t a demeaning role, and I think it sounds better than the cursed “junior project manager” some organizations assign. The point isn’t to get hung up on the title of project coordinator, but rather to embrace and complete the duties of the project coordinator effectively.

The project coordinator completes many of the project management duties, but with a bit more oversight from the project sponsor, an experienced project manager, or the functional manger. If you’re assigned the role of the project coordinator, do the job well as you work to advance in your organization or career—it’s a stepping stone to bigger and better things.

Exploring the Project Coordinator Roles and Responsibilities

The project coordinator, for the most part, does the same activities as the project manager, but with oversight from management. This oversight can come from a senior project manager, the project sponsor, or the functional manager. The project coordinator will work to identify the project requirements, write and decompose the project scope, and build out the activities with the project team. All of these activities, however, are usually done with more “check-ins” with the person overseeing the project management duties.

For example, the supervisor of the project coordinator would coach the project coordinator on the next activities to complete in their project management duties. The project coordinator would ask questions for clarity, listen to some advice, and then go on to complete the activities and report back to their supervisor. As the project coordinator becomes more and more confident and experienced, and the supervisor begins to trust and see the increasing competence of the project coordinator, there’ll be less and less coaching from the supervisor, and the project coordinator will complete more and more project management duties unsupervised.

If the project involves external customers, the project coordinator may not be working with customers directly and alone, but rather in the presence of the supervisor or project sponsor. This is not meant to be an insult to the project coordinator; instead, it ensures that the project coordinator is providing correct information, managing the relationship properly, and not affecting the business of the organization in a negative manner. Like all things, as the project coordinator gains experience and the supervisor learns to put more trust in the project coordinator, more responsibilities will shift directly to the project coordinator.

Supporting the Project Manager

While most of our conversation about the project coordinator so far has described the project coordinator working under the guidance of a supervisor role, you may encounter another function of the project coordinator. In some instances, the project coordinator may not be actually managing the project, but working with a project manager as more of an assistant. The project coordinator in this role will follow the leadership of the project manager and complete duties assigned by the project manager.

This type of project coordinator will help the project manager with day-to-day project management activities. This can include tedious and less-than-glamorous things such as keeping minutes in a meeting, replying to e-mails on behalf of the project manager, and completing errands and tasks that help the project move along. As the project coordinator gains more experience and the project manager learns to trust and lean on the project coordinator, there may be more assignments and duties that are project management–centric, such as scheduling, leading team-building activities, writing reports, and planning.

Just because a project coordinator is seen as a helper to the project manager doesn’t necessarily mean that this isn’t an important position. Some projects can be large in scope and unwieldy to manage alone. A detailed and organized project coordinator can be a boon for the project manager and the project’s success. Often the project coordinator and the project manager work as a team in the project, with the role of the project manager having a slightly senior role over that of the project coordinator. It’s important not to get hung up on who’s in charge, but to put the focus on getting the right things done to ensure that the project keeps moving toward its goal of completion.

Working with a Project Scheduler

A few years ago I was consulting as a project manager for a large insurance company. The organization assigned me 20–25 projects to manage at once. Of course, I was stunned, stupefied, and scratching my noggin. Twenty-five projects? How in the world can one project manager do that? Well, it turns out that these projects were all small-to-medium–scoped projects that each would take between one month and six months to complete. Second, the team assigned had done these types of projects over and over, so they knew what to expect in the workload—and, finally, I was assigned a project scheduler.

A project scheduler is the fabled, mythical creature of the project management landscape—managing a project with a full-time scheduler is like finding a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. It is fantastic! The project scheduler is an expert at helping the project manager schedule project tasks, build the schedule, and ensure that enough resources are available to complete the work. The project scheduler is a wonderful ally to have in any project: a good project scheduler can automate the scheduling, track resources, compile reports, and take a load off the project manager’s desk. A good scheduler with a great team is an absolute joy to work with.

Scheduling Project Activities

The project scheduler first needs something to schedule—that is, the project activities. This means you, the project manager, will first need to have worked through the scope definition, the WBS creation, and the activities list creation. The scheduler will then, with the project manager and project team, flesh out the project schedule based on the ordering of the events, constraints, and other details that affect the ordering of the activities. The project scheduler will most likely use advanced scheduling software (such as Primavera Professional Project Management or Microsoft Project) to schedule the work.

Using the scheduling software, the scheduler will follow some typical steps to build the schedule:

1. Define and enter the activities’ duration estimates.

2. Sequence the activities in the order in which they should happen.

3. Identify the resources who will work on different activities.

4. Arrange the paths to completion in a project network diagram.

5. Apply any constraints such as vacations, holidays, and company business cycles.

6. Discuss risks that may affect the schedule.

7. Gain consensus from the project manager and the project team on the schedule.

Your organization may have additional steps and requirements for creating the project schedule, but these are the most common steps when working with a project scheduler. These steps likely won’t be finalized in one meeting—in fact, the scheduler may collect information from the project team and project manager and then go off to work on the schedule. It takes concentration to build a comprehensive schedule, and there’ll likely be trade-offs and discussions with the project manager, the project team, and maybe even management, before the schedule is approved.

Managing Resources with the Project Scheduler

Once the schedule has been created and approved, the scheduler doesn’t go away. In fact, you’ll probably see more and more of the scheduler as the project moves forward. In my consulting assignment, the scheduler came to our weekly team meetings, and we quickly buzzed through the status of each assignment, how many hours the team member had worked on the assignment, the percentage of the work completed, and how much longer the team may need on the task. This gave everyone a chance to report on their work, to anticipate any tasks that may be late, and to be held accountable to one another in the project reporting.

The scheduler can also help the project manager communicate the schedule to management and stakeholders. The scheduler can create reports that will help the project manager communicate several things to management:

• Work completed in ratio to work remaining Reports how many items or assignments have been completed, how many assignments remain to be completed, and, in some cases, how much money has been spent on labor to complete the work. This helps with predicting project completion.

• Resource allocation Reports how many hours of labor are being allocated to the project in a given time period, such as so far in the project or in the current week or month, and expectations for the remainder of the project.

• Resource over allocation Identifies any resources that are working more than a predetermined number of hours on the project in a given time period. For example, a team member can work no more than 40 hours per week in a project. If that person is schedule to work 47 hours this week in the project, they are overallocated 7 hours.

• Resource shortage Consider the activities that don’t have resources assigned or available on the project team. Keep an eye towards tasks that have a resource shortage and plan for how the resources will be acquired for the activities. If the project is running against a deadline, consider adding resources to activities that can be reduced with additional effort.

• Benched resources Identifies resources that aren’t being used in the project at any given time. This helps the project manager see opportunities, or risks, that need to be addressed.

• Inter-project resource management A scheduler can help identify who’s being used on what projects in the organization and identify conflicts or dependencies between projects. This helps with better planning and improved communications among the project managers and the project teams.

The role of the project scheduler is to help the project manager better create the schedule, identify risks and opportunities in the project, collect activity completion updates, and create a more cohesive environment in the project. If you’re lucky enough to have a scheduler on your project, don’t get in their way; let them do their jobs, rely on their expertise, and know that they are available to help you manage a better project.

Managing Team Issues

Without a doubt, people will have conflicts. Fortunately, in most offices, people are mature enough to bite their tongues, try to work peacefully, and, as a whole, strive to finish the project happily and effectively together. Conflict is natural and can be a healthy event to discover new ideas, better approaches, and solutions for the project, if the conflict is done with mutual respect.

Most disagreements in IT project management happen when two or more people feel very passionate about a particular IT topic. For example, one person believes a network should be built in a particular order, while another feels it should be constructed using a different approach. Or two developers on a project get upset with each other about the way an application is created. Generally, both parties in the argument are good people who just feel strongly about a certain work methodology.

There are, of course, a fair percentage of contrary and pessimistic people in the world. These people don’t play well with others and are obnoxious at times. They don’t care about other people’s feelings, and much of the time they don’t care about the success of your project.

Unfortunately, you will have to deal with disagreements, troublemakers, and obnoxious people to find a way to resolve differences and keep up the project’s momentum.

Dealing with Team Disagreements

There will be instances when the project team, management, and other stakeholders disagree on the progress, decisions, and proposed solutions within the project. It’s essential for the project manager to keep calm, lead, and direct the parties to a sensible solution that’s best for the project. Here are seven reasons for conflict in order of most common to least common:

1. Schedules

2. Priorities

3. Resources

4. Technical beliefs

5. Administrative policies and procedures

6. Project costs

7. Personalities

So what’s a project manager to do with all the potential for strife in a project? There are six different approaches to conflict resolution:

• Problem solving This approach confronts the problem head-on and is the preferred method of conflict resolution. You may see this approach as “confronting” rather than problem solving. Problem solving calls for additional research to find the best solution for the problem. Problem solving is a win-win solution that can be used if there is time to work through and resolve the issue. It works to build relationships and trust.

• Forcing The person with the power makes the decision. The decision made may not be the best decision for the project, but it’s fast. As expected, this autocratic approach does little for team development and is a win-lose solution. Use it when the stakes are high and time is of the essence, or if inter-team relationships are not important.

• Compromising This approach requires both parties to give up something. The decision made is a blend of both sides of the argument. Because neither party really wins, it is considered a lose-lose solution. The project manager can use this approach when the relationships are equal and you can’t “win.” This approach can also be used to avoid a fight.

• Avoiding The person who can make the decision in the disagreement, such as the project manager, simply avoids the decision. This approach avoids the conflict, but it can cause resentment on the project team as people wait for the project manager to make a decision. The project manager could be avoiding the issue because it seems trivial, it could disrupt progress, or they are hoping the project will finish with a needed solution.

• Smoothing The project manager smooths out the conflict by minimizing the perceived size of the problem. It is a temporary solution but can calm team relations and boisterous discussions. Smoothing may be acceptable when time is of the essence or when any of the proposed solutions would work. This is considered a lose-lose situation, because no one really wins in the long term. The project manager can use smoothing to emphasize areas of agreement between the stakeholders in contention and minimize areas of conflict. Use it to maintain relationships and when the issue is not critical.

• Withdrawing This is the worst conflict resolution approach, because one side of the argument walks away from the problem—usually in disgust. The conflict is not resolved, and it is considered a yield-lose solution. The approach can be used, however, to provide a cooling-off period or when the issue is not critical.

Phases of Team Development

Teams develop over time—not instantaneously. As a project team comes together, there are likely people on the team who have worked together previously, just as there may be people on the project team who have never met. Because projects are temporary, the relationships among project team members are also often viewed as temporary. The project manager can see—and sometimes guide—the natural process of team development.

The goal of team development is not for everyone to like each other, have a good time, and create lifelong friendships. All of that is nice, but the real goal is to develop a team that can accurately and effectively complete the project scope. Within team development, the project team will pass through five stages:

• Forming In this stage, the project team comes together and learns about one another. Project team members begin to understand each other and find out who’s who and what others are like.

• Storming This stage promises action. There’s a struggle for project team control and momentum of who’s going to lead the team. During this phase, people figure out the hierarchy of the team and the informal roles of team members.

• Norming Once control on the project team has been established, the project team’s focus shifts toward the project work. This is where people learn to work together.

• Performing Team members have settled into their roles and can focus on completing the project work as a team. During this stage, a synergy is developed; this is the stage at which high-performance teams come into play.

• Adjourning The project team, like the project, is not a permanent fixture in the organization. At some point, the members of the team disperse to work on other projects and join different project teams.

Project Management Is Not a Democracy

Despite what some feel-good books and inspiring stories would like to have you believe, project management is not a democracy. Someone has to be in charge, and that someone is you, the project manager. The success of the project rests on your shoulders, and it is your job to work with your team members to motivate them to finish the project on schedule.

This does not mean that you have permission to grump around and boss any member of your team. It also does not mean that you should step in and break up any disagreements between team members. In fact, you should allow some discussion and some disagreement among the team members.

This is what teams have to do: they have to work things out on their own. Team members have to learn to work together, to give and take, to compromise. Step back and let the team first try to work through disagreements before you step in and settle issues. If you step into the mix too early, your team members will run to you with every problem.

Ultimately, you are in charge. If your team members cannot, or will not, work out a solution among themselves, you’ll be forced to make a decision. When you find yourself in this situation, you can work through the problem using several recommended steps to conflict resolution:

1. Pay attention. Meet with both parties and explain the purpose of the meeting: to find a solution to the problem. If the parties are amicable, this meeting can happen with both parties present. If the team members detest each other, or the disagreement is a complaint against another team member, meet with each member in confidence to hear that person’s side of the story.

2. Listen. Ask the team members to describe the problem. Allow each to speak their case fully without interrupting, and then ask questions to clarify any of the facts.

3. Resolve. Often, if the meeting takes place with both conflicting team members, a resolution will quickly boil to the surface. Chances are you won’t even have to make a decision. People have a way of suddenly wanting to work together when a third party listens to their complaints. They both realize how foolish their actions have been, and one, or both, of the team members will cheer up and decide to work together.

4. Wait. If the resolution doesn’t happen in your meeting, don’t make an immediate decision. Tell the team members how important it is to you, and to the project, that they find a way to work together. Sometimes even this touch of direction will be enough for the team members to begin compromising. If they still won’t budge, tell them you’ll think it over and will make a decision within a day or two—if the decision can wait that long. By delaying an immediate decision, you allow the team members time to think about what has happened and give them another opportunity to resolve the problem.

5. Act. If the team members will not budge on their positions, then you will have to make a decision. And then stick to it. If necessary, gather any additional facts, research, and investigations. Drawing on your evidence, call the team members into a meeting again and acknowledge both of their positions on the problem. Then share with them, based on your findings, why you’ve made the decision that you have made. In your announcement, don’t embarrass the team member who has been put out by your decision. If the losing team member wants to argue their point again, stop them. Don’t be rude, but stop them. The team members have both been given the opportunity to plead their case, and once your decision has been made, your decision should be final.

Dealing with Personalities

In any organization, you’ll find many different personality types, so it’s likely that there are some people in your organization who just grate on your nerves like fingernails on a chalkboard. These individuals are always happy to share their discontent, their opinion, or their “unique point of view.” Unfortunately, you will have to find a way to work with, or around, these people.

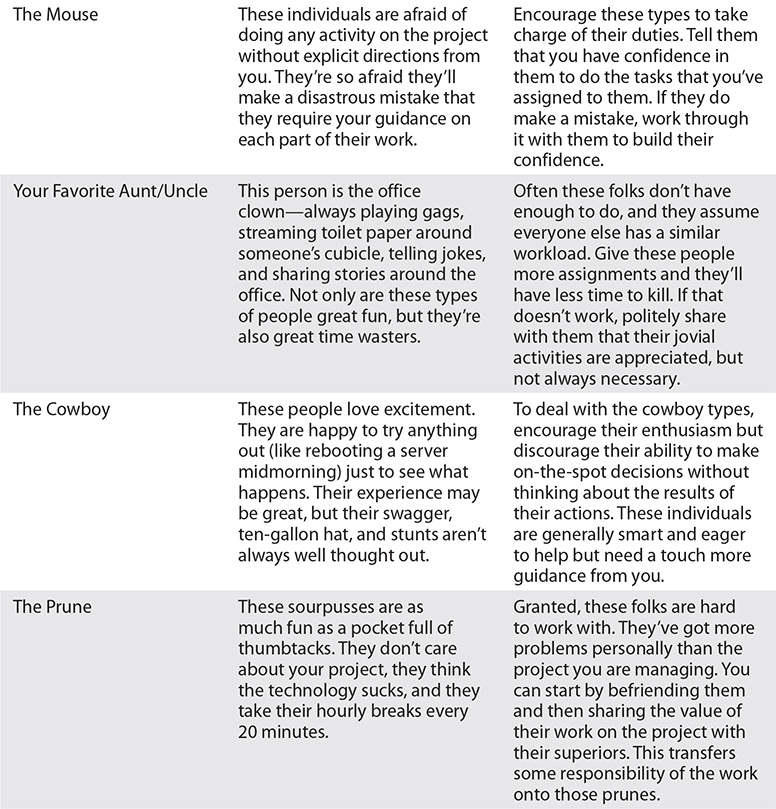

Here are some personality types you may encounter and how you can deal with them:

Leading People in Adaptive Projects

In an adaptive project you wouldn’t say that you’re managing people, but leading people. In adaptive projects, especially using the most-popular Scrum approach, project teams are self-led and self-managed. The team decides who’ll do what and who’s leading what portion of the project work, and they’ll work together to resolve differences and find good solutions. In Scrum, there are three primary roles to know:

• Scrum master This is analogous to the project manager, but the scrum master role is to coach, mentor, and ensure that everyone is following the rules of scrum. This role is different than a project manager’s role in a waterfall project, as the scrum master isn’t directing people what to do throughout the project, but coaching people on what to do. The scrum master is sometimes called the servant leader, as they’ll get the team what they need to get the work done.

• Product owner This role is the business liaison between the team and the business people. This role is responsible for gathering, organizing, and documenting the project requirements. You may recall that the product owner is responsible for prioritizing the requirements, called user stories, in the product backlog.

• Development team The development team describes the core workers of the agile project. The development team is self-led and self-organized. They’ll select chunks of work from the product backlog, determine who’ll do what specific tasks to create the work, and support one another to get the work done. The development team is protected from interruptions by the scrum master, and they’re free to innovate and experiment to get things done.

Ceremonies are events or meetings in an adaptive project, specifically a scrum project. Ceremonies are key events that are timeboxed and represent the iterative nature of adaptive projects. Each role has specific responsibilities in each ceremony.

• Sprint planning Sprint planning is the first ceremony of each sprint. During sprint planning the development team, product owner, and scrum master work together to select the most important items from the product backlog that the development team will create during the sprint. The development team will create a sprint backlog of tasks and they’ll decide who’ll do what tasks in the sprint.

• Daily scrum Every workday in the sprint the development team and the scrum master meet for 15 minutes to answer three questions of each person: What did you accomplish since our last meeting? What will you work on today? Are there any impediments or blockers preventing your progress? The daily scrum is sometimes called a stand-up meeting as the participants stand to keep conversations and the meeting to the 15-minute duration or less.

• Sprint review At the end of the sprint, the development team, product owner, scrum master, and key stakeholders meet for a demonstration by the development team. The sprint review is the development team demonstrating what they have accomplished during the last sprint. It’s an opportunity for the team to show their work and for the stakeholders to offer any feedback, ask for changes, or approve the work completed so far in the project.

• Sprint retrospective This final ceremony of the sprint allows the development team, product owner, and scrum master to review what has and has not worked well in the project. It is not an opportunity to blame and argue with one another, but to have open, transparent discussions about what needs improvement in the project. This ceremony is led by the scrum master and the focus is on how the team can improve the project during the next sprint.

After the sprint retrospective, the team moves back to sprint planning and the entire cycle begins again. It is an iterative approach to getting work done, and the ceremonies help define the roles and responsibilities of each team member. For new agile teams, the agile framework can be a little confusing, so the scrum master ensures that everyone follows the rules and guidelines, but after a few sprints of project work, the development and stakeholders will grasp the rules of agile and things will begin to run much more smoothly.

Use Experience

The final method for resolving disputes among team members may be the most effective: use experience. When team members approach you with a problem that they just can’t seem to work out between themselves, you have to listen to both sides of the situation.

If you have experience with the problem, then you can make a quick and accurate decision for the team members. But what if you don’t have experience with the technology and your team members have limited exposure to this portion of the work? How can you make a wise decision based on the information in front of you? You can’t!

You will need to invent some experience. As with any project, you should have a testing lab to test and retest your design and implementation. Encourage your team members to use the testing lab to try both sides of the equation to see which solution will be the best.

If a testing lab is not available, or the problem won’t fit into the scope of the testing lab, rely on someone else’s experience. Assign the team members the duty of researching the problem and preparing a solution. They can consult books, the Internet, or other professionals who may have encountered a similar problem.

Disciplining Team Members

No project manager likes the process of disciplining a team member—at least they shouldn’t. Unfortunately, despite your attempts at befriending, explaining the importance of the project, or keeping team members on track, some people just don’t, or won’t, care. In these instances, you’ll have little choice other than to resort to a method of discipline. The discipline should be based on the defined consequences of non-performance.

Within your organization, you should already have a process for recording and dealing with disciplinary matter; this is an example of an enterprise environmental factor. The organizational procedures set by human resources, the PMO, or management should be followed before interjecting your own project team discipline approach. If there is no clear policy on team discipline, you need to discuss the matter with your project sponsor before the project begins. In the matter of disciplinary actions, take great caution—you are dealing with someone’s career. At the same time, discipline is required or your own career may be in jeopardy.

As you begin to nudge team members onto the project track, document it. Keep records of instances where they have fallen off schedule, failed to complete tasks, or have done tasks half-heartedly. This document of activity should have dates and details on each of the incidents, and it doesn’t have to be known to anyone but you. Hopefully, your problematic team members will turn from their wicked ways and accept your motivation to do their jobs properly. If not, when a threshold is finally crossed, then you must take action.

Following an Internal Process

Within your organization, there should be a set process for how an unruly employee is dealt with. For some organizations, there’s an escalation of a write-up, a second write-up, a suspension of work, and then ultimately a firing. In other organizations, the disciplinary process is less formal. Whatever the method, you should talk with your project sponsor about the process and involve them in any disciplinary action.

In all instances of disciplinary action, it would be best for you and the employee to have the project sponsor or the employee’s immediate manager in the meeting to verify what has occurred. Not only does this protect you from any accusations from the disgruntled team member, it also ensures that you, the project team member, and the manager all hear the same conversation about the performance at the same time.

Removal from a Project

Depending on the situation, you may discover that the team member cannot complete the tasks required on the project, and removal from the project may be the best solution. In other instances, the team member may refuse, for their own reasons, to complete the work assigned and be a detriment to the success of the project. Again, removal from the team may be the most appropriate action.

Removing someone from the project requires tact, care, and planning. A decision should be made between you and the project sponsor. If you feel strongly that this person is not able to complete the tasks assigned, rely on your documentation as your guide. Removal of a team member from a project may be harsh, but it’s often required if the project is to succeed.

Of course, when you remove someone from the project, you need to address the matter with the team. Again, use tact. A disruption in the team can cause internal rumblings that you may never hear about—especially if the project team member who was removed was everyone’s best friend. You will have created an instant us-against-them mentality. In other instances, the removal of a troublemaker may bring cheers and applause. Whatever the reaction, use tact and explain your reasons without embarrassing or slandering the team member who was removed.

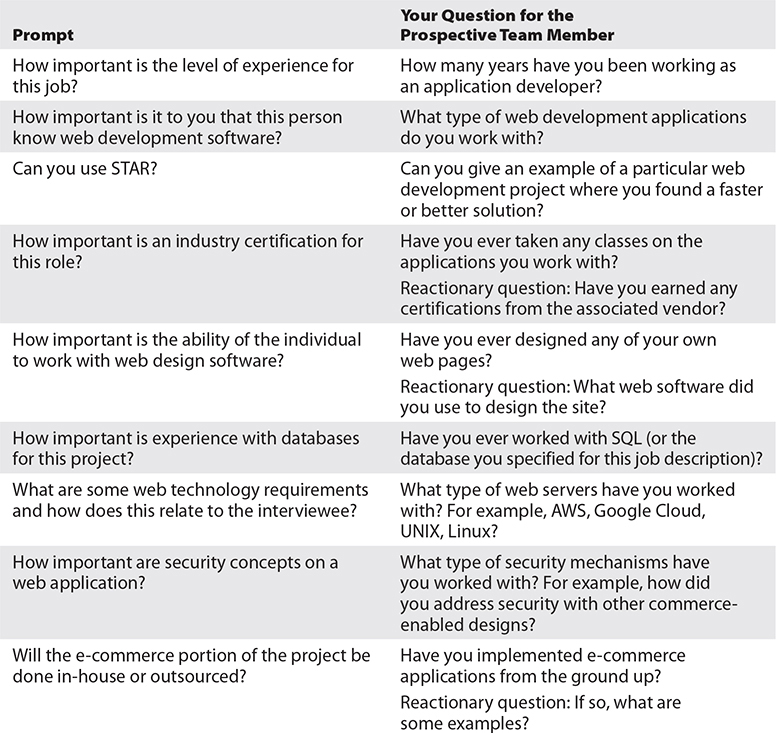

Using External Resources

There comes a time for every organization when a project is presented that is so huge, so complex, or so undesirable to complete that it makes perfect sense to outsource the project to someone else. In these instances, no matter the reason the project is being outsourced, it is of utmost importance to find the right team to do the job correctly.

Outsourcing has been the buzz of all industries over the last several years—and certainly many companies dealing with complicated IT implementations have chosen to “get someone else to do it.” There are plenty of qualified companies in the marketplace that have completed major transitions and implementations of technology—but there are also many incompetents that profess to know what they’re doing, only to botch an implementation. Don’t let that happen to you.

Finding an Excellent IT Vendor

Finding a good IT vendor isn’t a problem. Finding an excellent IT vendor is a problem. The tricky thing about finally finding excellent vendors is that, because they keep so busy (because of their talented crew), they are difficult to schedule time with. So what makes an excellent vendor? Here are some attributes:

• Ability to complete the project scope on schedule

• Vast experience with the technology to be implemented

• References that demonstrate customer care and satisfaction

• Proof of knowledge on the project team (experience and certifications)

• Adequate time to focus on your project

• A genuine interest in the success of your organization

• A genuine interest in the success of your project

• A fair price for completing the work

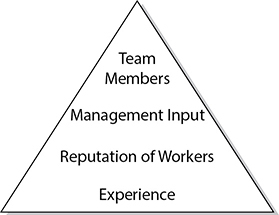

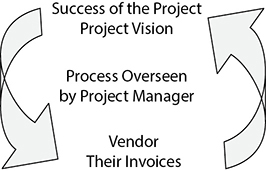

Finding an excellent vendor to serve as your project team, or to integrate into your project team, is no easy task. Remember, the success of a project is only as good as the people on the project team. It’s not just the name of the integrator, but the quality of the individuals on the integrator’s implementation team that make the integrator great (or not so great). Never forget that fact. Figure 7-3 demonstrates how a vendor can be integrated as your project team. Often, the success of the project is dependent on the vendor’s implementation. When the vendor has completed their work, the buyer needs to complete the contract and pay the vendor according to the terms of the contract. The project manager should oversee the process as a contract that is binding for both parties—vendor and buyer.

Figure 7-3 Vendors need to adhere to the terms of the contract and support the project vision.

Size doesn’t always matter. Those monstrous integrators and technical firms that have popped up in every city over the past few years don’t always have the best people. Some of the best integrators you can find are small, independent firms that have a tightly knit group of technical wizards. Do some research and consider these smaller, above-average tech shops. You may find a diamond in the rough.

To begin finding your integrator, you can use several different methods:

• References Word of mouth from other project teams within your organization, contacts within your industry, or even family and friends are often the best way to find a superb contractor. A reference does something most brochures and sales letters cannot: it comes from a personal contact and lends credibility.

• Internet If you know the technology you are to be implementing, hop on the Internet and see who the manufacturer of the technology recommends. Once you’ve found integrators within your community, peruse their websites. Use advanced searches to look for revealing information about them on other websites, in social media, or in newspapers and trade magazines. Know who you are considering working with before they know you. Google is your friend; look for reviews, articles, and testimonials.

• Phone and web interviews When all else fails, call and interview the prospective vendor over the phone or through web conferencing software. Prepare a list of specific questions that you’ll need answered. Pay attention to how the phone is answered, what noise is in the background, and how professional and organized the individual on the phone is. Was the person rude? Were they happy to help? Take notes and let the other person do much of the talking.

• Trade shows If you know your project is going to take place in a few months, attend some trade shows and get acquainted with some potential vendors. Watch how their salespeople act. Ask them brief questions on what their team has been doing. Collect their materials and file them away for future review.

• Previous experience Never ignore a proven track record with a vendor. Past performance is always a sure sign of how the vendor will perform with your project.

Interviewing the Vendor

Once you’ve narrowed your search to two or three vendors, it’s time to interview each one to determine to whom the project will be awarded. In the interview process, which the vendor will probably consider a sales call, remind yourself that this is a chance to find out more information about the vendor.

Document all parts of the meeting: How difficult was it to arrange a meeting time? How polite was the salesperson? Did the salesperson bring a technical consultant to the meeting? All of these little details will help you make an informed decision. Again, as mentioned in Chapter 6, in such meetings, pay attention to the following regarding vendors’ representatives:

• Do they pay attention to details? Are they on time? Dressed professionally and appropriately for your business? Are their shoes shined and professional? How vendors pay attention to the details in their appearance and presentation to win your business will be an indicator of how they will treat you once they’ve won your business.

• How organized are their materials? When a salesperson opens their briefcase, can they quickly locate sales materials? Are the brochures and materials well prepared and neat, and not wrinkled or dog-eared? Again, this shows attention to detail, something every project requires from the start.

• What is their body language saying? Pay attention to how they are seated, where their hands are, and how animated their answers become. A salesperson should show genuine interest in your project and be excited to chat with you. If they seem bored now, they will likely be bored when you call them to discuss concerns down the road.

• What does your gut say? Gut instinct is not used enough. The meeting with the salesperson should leave you with a confident, informed feeling. If your gut tells you something is wrong, then chances are something is. If you’re not 100 percent certain (and you probably shouldn’t be certain after only one meeting), do more research or ask for another meeting with the project integrators.

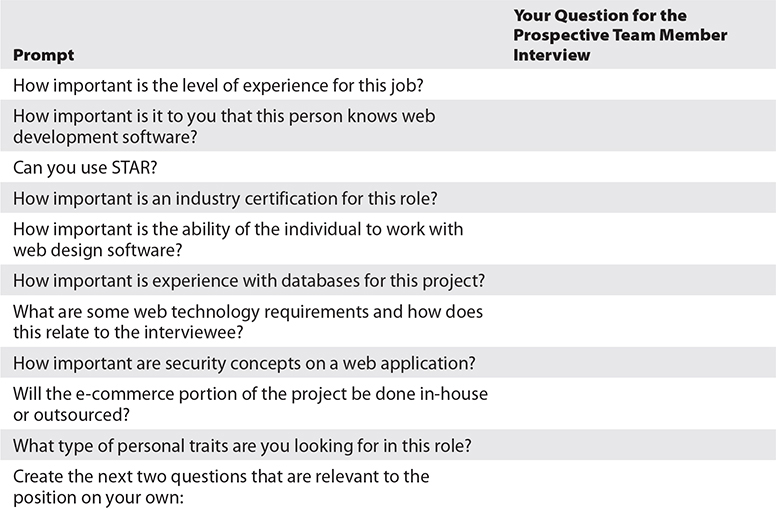

Looking for a STAR

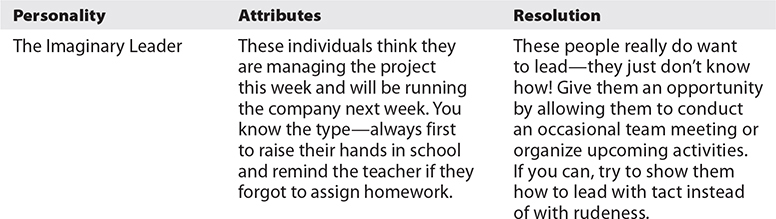

When you are interviewing the potential vendors, you need to ask direct, hard-hitting questions to slice through their sales spiels and get to the heart of the project. One of the best interview techniques, especially when dealing with potential integrators, is the STAR methodology. Figure 7-4 shows STAR, an acronym for situation, task, action, result.

Figure 7-4 STAR is an interview methodology to gauge experience.

When you use the STAR method, you ask a situational question, such as, “Can you tell me about a situation where you were implementing a technology for a customer and you went above and beyond the call of duty?”

The vendor should answer with a specific situation, followed by the task of the situation, the action the vendor took to complete the task, and then the result. If the potential vendor doesn’t complete the STAR, add follow-up questions, such as, “How did the situation end?” to allow the vendor to finish the STAR question.

This interview process is excellent, as it allows the project manager to discern fact from fiction based on the vendor’s response. Try it!

After Hiring the Consultant

Consultants know what they know—and what they do not know can hurt them and your project. In other words, consultants need to learn about your environment, how your standard operating procedures work, whom they should talk to, and so on. Consultants need to know how to get things done within your organization. You cannot throw a consultant into your organization and expect them to have the same level of detail, same level of expertise, and same organizational knowledge that you have. It takes some time and some guidance.

For this reason alone, you should demand and require that the consultant attend project meetings, be involved with the project team, and take an active role in meeting the project team members and stakeholders. With the availability of web collaboration software, it’s easier than ever to remove the locale constraint to hiring great consultants. Consultants need to get involved in order to be successful and productive. Most consultants and experts, if they are worth their salt, will be eager to follow these rules and requirements. Often it’s the project manager who wants the consultant to feel comfortable and not get into the mix of things so quickly. But this limits the consultant’s ability to contribute.

CompTIA Project+ Exam Highlight: Project Team Management

You’ll be faced with several questions on managing and developing a project team for your CompTIA Project+ exam. Each organization is different—the approach you use in your work environment may be entirely different from one that works for that neat company down the street. The enterprise environmental factors, policies, and human resource procedures all affect how the project manager is allowed to manage the project team. On that note, you can expect the CompTIA Project+ exam to consider how every organization may have a different approach to human resources and how they’ll stick to the core, generally accepted principles of project management and human resource management.

1.2 Compare and contrast Agile vs. Waterfall concepts Project teams in a waterfall, or predictive, project work differently than teams in an agile project. Predictive project teams report to the project manager and the team follows orders and the project plan. An agile project is decentralized and the project manager role is really split across three roles: the product owner, the scrum master or coach, and the development team members. The team members in an agile project are self-led and self-organizing, meaning they don’t need a project manager to tell them what to work on next. The coach or scrum master isn’t there to delegate work, but to ensure that everyone is following the rules of the agile project management approach.

1.10 Given a scenario, perform basic activities related to team and resource management This was the primary objective covered in this chapter. Forming and leading a project team affects the entire project, as the people on your team are doing the work that can directly affect the quality, acceptance, and long-term support of the project deliverables. The scope baseline, and in particular the WBS, can help you identify the human resources you’ll need on your project team. By examining the deliverables of the WBS and the related activity list, you can assess the types of skills the project team members will need to complete the project work. A resource breakdown structure allows you to map needed resources to the WBS components for planning, cost, and schedule duration estimating. You can also use the WBS to plan for resource availability; if a resource is already assigned to one project activity, that person can’t complete another activity at the same time.

Resource management includes understanding the allocation of resources in the project. Recall that the project scheduler can help you identify overallocation, benched resources, shortages, and inter-project dependencies that you’ll need to address in the project. You’ll also need to work with management and other project managers for resources that are shared on other projects and operational activities.

Managing the project team starts with developing the project team and allowing the team to develop itself through the natural phases of team development. Team development moves through forming, storming, norming, performing, and adjourning during the project life cycle. Team development activities can help facilitate the team development process. Sometimes project team members may be in disagreement with one another over assignments, approaches to the project work, and even their availability among multiple projects and operations. Based on the scenario, the project manager can use one of six conflict resolution methods: problem solving, forcing, compromising, avoiding, smoothing, and withdrawing.

Virtual teams are project teams that are not co-located but work together through subteams, web collaboration software, teleconferences, and videoconferences. When managing a virtual team, the project manager must address challenges such as time zones, language differences, and cultural differences that can affect the project execution. For your CompTIA Project+ exam, you can expect questions about overcoming technical barriers and assumptions that can affect your ability to communicate with the project team and the team’s ability to communicate with one another.

1.11 Explain important project procurement and vendor selection concepts It’s not unusual for a project to have contractors serve as part of the project team. When hiring a contractor, you’ll follow the procurement processes and procedures within your organization, just like you were purchasing physical resources. You’ll often begin with a statement of work describing what the person will do in the project, and a request for quote, invitation to bid, or a request for a proposal for the vendor. Quotes and bids are price-only documents, while the proposal details possible solutions and price.

2.4 Given a scenario, perform activities during the project execution phase The project team executes the project plan and the tasks required to create the product. If the team doesn’t have the skills necessary, you’ll need to train the team. Training helps the team members gain the knowledge and competence needed to do the project work, but also enhances the organization’s ability to do future work. This exam objective also touches base on managing conflicts among the project team members. Recall that you can use problem solving, forcing, compromising, avoiding, smoothing and withdrawingdepending on the significance of the conflict and the urgency of the project.

Chapter Review

Teamwork is the key to project management success. As a project manager, you must have a team that you can rely on, while at the same time, the team must be able to turn to you for guidance, leadership, and tenacity. When creating a team, evaluate the skills required to complete the project and then determine which individuals have those attributes to offer. Interviewing potential team members allows you to get a sense of their goals, their work ethics, and what skills they may have to offer.

Subteams are a fantastic way to assign particular areas of an IT project to a group of specialists or to a geographically based team for implementation. When creating subteams, communication between the project manager and the team leaders is essential. Subteams require responsible leaders on each team and a reliable, confident project manager.

You may be serving as a project coordinator rather than a project manager. This role often performs the same duties as the project manager, but with more oversight from management, the project sponsor, the PMO, or even a senior project manager. In some instances, the project coordinator role may actually be an assistant to the project manager. In this capacity, the project coordinator will help the project manager with many project duties to keep the project moving toward completion.

Project schedulers are a resource for the project manager. A project scheduler helps the project manager develop and manage the project schedule—a boon to any busy project manager. A project scheduler works with the project team to identify activity duration, sequencing, management, risk, and opportunities. The project scheduler will also meet with the team on a regular basis to record progress, hours worked, and hours remaining and to make predictions about the project completion date.

Disagreements can flair up among team members, and you must have a plan in place before disagreement happens. Document problems with troublesome team members in the event that a team member needs to be reprimanded or removed from the team. The project sponsor should be kept abreast of the situation as the project continues.

Should the scope of the project be beyond the abilities of the internal team, the project can be outsourced. When outsourcing the project, you need to use careful consideration in your selection of an integrator. Project managers should rely on references of vendors, their ability to work with the technology, gut feelings, and word of mouth to make a decision.

Building a project team is hard work, but it is also an investment in the success of the project. Once again, the success of any project is only as good as the members on the project team.

Exercises

These exercises allow you to apply the knowledge you have learned in this chapter and are followed by possible solutions.

Exercise Solutions

The following offer possible solutions for the chapter exercises.

Questions

1. When the project manager is creating a project team, why must they be aware of the skills of each of the prospective team members?

A. It helps the project manager determine the budget of the project.

B. It helps the project manager determine how long the project will take.

C. It helps the project manager determine whether they want to lead the project.

D. It helps the project manager assign tasks.

2. You are the project manager for your organization and you’re creating the project team. Of the following, which two are methods the project manager can use to assess internal skills?

A. Prior projects

B. Reports from other project teams

C. Recommendation of management

D. Projects the project manager has worked on

3. When requesting an internal résumé to recruit team members, why must the project manager use extreme caution?

A. Résumés have the connotation of getting, or keeping, a job.

B. Résumés have the connotation of pay raises.

C. Résumés have the connotation of relocating users.

D. It is illegal within the United States to ask for a résumé after the individual has been hired.

4. Esperanza is the project manager for her organization, and management has instructed her to create some team development exercises. Of the following, which one is not an example of team development?

A. Training for the project work

B. Industry certifications

C. Team events such as rafting

D. Forming, storming, norming, performing, and adjourning

5. Marty is the project manager for his company, and he believes that he’ll need to train the project team. Management is concerned about the cost of the training. Marty tells management that this training isn’t really an expense for the project. When is training considered an expense?

A. When the cost of training is beyond the budget of an organization

B. When the time it takes to complete the training increases the length of the project beyond a reasonable deadline

C. When the training experience does not increase the ability of the team to implement the technology

D. When the training experience does not increase the individual’s salary

6. The project team is in disagreement over which OS to use on a new server. The project manager tables the issue and says the decision can wait until next week. This is an example of which project management negotiating technique?

A. Confrontational

B. Yielding

C. Coercive

D. Withdrawal

7. As a project manager, you need to manage your project team, but you also need to lead your project team to finish the project. You need reliable, dedicated workers on your project team. What is the best way to create reliable, hard-working teams?

A. Fire the team members who do not perform.

B. Set an example by being reliable and hard working.

C. Promise raises to the hardest-working team members.

D. Promise vacation days for all who are hard working.

8. A project scheduler can help the project manager identify resource overallocation. What is the best example of resource overallocation?

A. Too many project team members on one task

B. Too many project team members on the project

C. An individual with too much work in the project timeline

D. An individual assigned more than 40 hours in a week

9. Why is the WIIFM principle a good theory to implement with project management?

A. It shows the team how the success of the project is good for the whole company.

B. It shows the team how the success of the project is good for management.

C. It shows the team how the success of the project will make the company more profitable.

D. It shows the team how the success of the project will impact each team member personally.

10. You are the project manager for your organization and will manage 23 people as part of your project team. Management has encouraged you to create subteams for this implementation project. What is a subteam?

A. A specialized team that is assigned to one area of a large project or to a geographical area.

B. A specialized team that will be brought into the project as needed.

C. A collection of individuals that can serve as backup to the main project team.

D. A specialized team responsible for any of the manual labor within a project.

11. What is the key to working with multiple subteams?

A. A team leader on each subteam

B. Multiple project managers

C. Communication between team leaders and the project manager

D. Communication between team leaders, the project manager, and the project sponsor

12. Of the following, which is a good team-building exercise?

A. Introductions at the kick-off meeting

B. A weekly lunch meeting

C. A team event outside of the office

D. Team implementation of a new technology over a weekend

13. Why should a project manager conduct interviews for prospective team members?

A. To determine if a person should be on the team or not

B. To learn what skills each team member has

C. To determine if the project should be initiated

D. To determine the skills required to complete the project

14. What is the purpose of conducting interviews of existing team members?

A. To determine if the project should be outsourced

B. To determine the length of the project

C. To determine the tasks each team member should be responsible for

D. To determine if additional project roles are needed

15. When a project manager sends a vendor an RFP, what are they asking for?

A. A proposal so that a decision can be made based on price

B. A proposal so that a decision can be made based on the proposed solution to the WBS

C. A proposal so that a decision can be made based on the proposed solution for the statement of work

D. A proposal so that a decision can be made based on the proposed schedule

Answers

1. D. The project manager should know in advance of the WBS creation the skills of the team members so that they can assign tasks fairly. A skills assessment also helps the project manager determine what skills are lacking to complete the project.

2. A, C. Experience is always one of the best barometers for skills assessment. If the prospective team member has worked on similar projects, that person should be vital for the current implementation. Recommendations from management on team members can aid a project manager in assigning tasks and recruiting new team members.

3. A. Résumés can show the skill sets of prospective team members, but asking for a résumé can imply that the employee is getting, or keeping, a job. In lieu of résumés, project managers can ask employees for a list of accomplishments and skills to determine the talents of recruits.

4. B. Industry certifications are a valuable source for proving that individuals are skilled and able to implement the technology. Certifications, on their own, however, do not provide team development.

5. C. Training is an expense rather than an investment when the result of the training does not increase the team’s ability to complete the project. A factor in determining whether training should be implemented or not is the amount of time required for the training and its impact on a project’s deadline.