Chapter 2

The Science and Art of Living Longer and Living Better

Everybody’s Doing It

ON BEING 100

INCREASING LONGEVITY

LIFESTYLE IMPROVEMENTS THROUGH TECHNOLOGY

USING COMPUTERS, TABLETS, AND SMARTPHONES

LIFESTYLE CHOICES

THE BIG THREE

HEALTHY DIET

THE BENEFITS OF EXERCISE

SOCIALIZATION AND QUALITY OF LIFE

THE IMPORTANCE OF FAMILY

INTERESTS AND AVOCATIONS

There is both a science and an art to longevity. The collective judgment of our centenarians is that living long and living well result from various combinations of genes, lifestyle, positive attitude, and luck.

Ongoing research into longevity seems to bear this out. Moreover, recent developments in technology and its use in genetic research and medicine shine a whole new light on increasing longevity—with the promise of making it available to everyone. Here, we take a look at some of the most exciting advances that will impact our well-being in the near future, that is, the “science” of longevity.

This chapter also illuminates the significance of lifestyle choices of diet, exercise, and socialization as contributing to successful aging. Through the examples, perspectives, and advice of our centenarians, we explore these factors that make up the “art” of longevity.

What we see in the lifestyles of centenarians in this book is that there is no one path to 100 and not one model centenarian. Each of us can learn from the myriad examples of those who have reached the century mark, and apply what we think would work for ourselves. And by taking advantage of new advances in technology and medicine, we have opportunities to enhance our longevity.

ON BEING 100

“Too much of a good thing is wonderful!”

Mae West

The vast majority of our centenarians say they are pleased they have lived to be 100 or more and are enjoying life. Most were surprised, though, that they had made it to the century mark. Apart from the obvious pleasure of just being alive, they responded to the question of how it feels to be 100 or more years old by making positive statements such as:

“It’s wonderful to still be able to enjoy so many things.”

Lucille Burkhart, 100

“You get to see so many new inventions, progress.”

Berte Weichmann, 100

“People take an interest in you because you’ve lived through so much.”

Margaret Stowe, 102

“I like surprising people when they learn my age.”

Mildred Fisher, 100

“I enjoy having good health and being with family and friends.”

Ethel Barnhardt, 100

“When you’re 100, you can say what you want.”

Eloise Wright, 100

“The best part is seeing your family grow.”

Robert Martin, 100

“Being medically and financially able to handle my life, and having family and friends who care.”

Virginia Babb, 100

“The joy of celebrating each day.”

Rena Lowry, 102

“Read all about it!”—Newsman Ron Gilbert, 100

Ron Gilbert

“At age 13, I was rejected for eighth-grade basketball because the family doctor said I had a defective heart valve. At 18, I was rejected for college physical education, because the examiner said I had leakage of the heart. At 30, I was rejected for military service; my slip said, ‘Systolic murmur at apex, accentuated by exercise.’

“I shrugged it off and lived a fairly normal life for the next 40-some years, but at age 77 a cardiologist told me that I had 99 percent blockage of a coronary artery and had to have angioplasty. I scheduled it, but the cardiovascular surgeon postponed it twice because of my travel schedule and then canceled.

“So why have I lived to be 100 years old? I don’t know. I have said jokingly that the only virtue I ever practiced was moderation. I smoked for 57 years, but mostly a pipe. I took a drink when I felt like it, but after a few youthful excesses I seldom took more than one or two. I ate all I wanted (when I could get it) and everything I wanted (when I could afford it). For 30 years I worked nights as a reporter in smoke-filled newsrooms.

“There were some positives. I had good genes. My parents were 92 and 94. My grandparents all lived into their 70s, and one great-grandmother lived to be 88. My mother and my wife persuaded me to eat some of the things that were good for me. My night work gave me daytime leisure that I spent working in my big garden and big yard.

“How much longer? Nobody knows. I still have my sense of humor, and I can still sing and play bridge and work crossword puzzles; I use a computer and e-mail. And I ride my motor scooter across the retirement village to visit a special lady. Life is good.”

INCREASING LONGEVITY

The twentieth century saw the greatest increase in longevity in history by approximately 30 years. Improved opportunities to achieve and maintain the good health that makes longevity possible and the development of lifesaving and life-extending medical, scientific, and technical advances explain this phenomenon.

Floyd Ellson, 100, says, “The extra years have allowed me to be around to welcome great grandchildren, and to see my dream come true: my four children and 10 grandchildren completing college. I enjoy being part of their lives; they make my life interesting. I’m glad to be here.”

Centenarians express gratitude for the extra years beyond the average lifespan. Dorothy Custer, 100, of Idaho, says, “Spreading joy and laughter is what I love to do.” Dorothy has had a gift for entertaining others since childhood and has participated over the years in local theatrical productions. She has written skits and made her costumes and performed in them. “I learned to play the harmonica when I was 12, and I still do. But my gift is for stand-up comedy,” she tells. In her later years she joined a group called the Good Sam Traveling Club. “We go all over performing at various functions—we’re in demand!” Dorothy has developed 13 characters for whom she continues to write skits and make costumes. The most popular is Granny Clampett from the Beverly Hillbillies.

Dorothy’s starring role came at 100, when she was named Pioneer of the Year. “It’s worth living long so that I get to do more of the things I love.”

Fortunately, there are new medical advances available and on the horizon to help others do the same. For example, anti-aging drugs are being researched that show promise of increasing longevity, according to genetics professor David Sinclair of Harvard University: “In effect, they would slow aging.”

Matters of the Heart

In 1977, Dr. Michael Heidelberger, then 89 and still working, became the oldest person ever to have a heart valve replacement. At the age of 98 he had a pacemaker implanted. These interventions not only saved his life, but also allowed him to continue to work. A pioneering researcher, he is considered the father of modern immunology. In 1989, at the age of 100, he was still in his laboratory every day at New York University Medical Center, where he continued his research until age 102.

“I’ve seen a lot of medical advances,” Garnett Beckman, 102, says. “Within my lifetime, I’ve seen the development of the Salk vaccine for polio, penicillin, and antibiotics, advances in X-rays and the development of the MRI and CT scans, to name a few, and heart repair, which I’ve had.”

In the late 1990s, Garnett, then approaching her 90s, began experiencing shortness of breath, which limited her activities such as hiking the Grand Canyon. “I’d made over 20 excursions there, starting in my mid-70s when I moved to Arizona, and I wasn’t ready to quit just yet. At my age (even 20 years after Dr. Heidelberger’s surgery) I had a heck of a time finding a doctor who would do the valve repair. But finally, I told him that if I was willing to take the risk he should be, too.” Garnett had the operation and continued her active lifestyle. She now walks a mile every day and teaches bridge to professional women who never had time to learn.

The techniques of heart valve replacement have significantly advanced since Garnett’s operation, and certainly since that of Dr. Heidelberger. It is now possible to perform this procedure in a minimally invasive manner, even on people in their 80s and 90s, giving them many more years of life. Such minimally invasive procedures increase the possibility of extending life, and the quality of life, to many more candidates of all ages.

Among other recent advances in the repair of age-related heart problems is new technology enabling the inside of the heart to be viewed in 3D. The use of this technology is helpful in resolving problems such as irregular or too rapid heartbeats or atrial fibrillation. Procedures can now be performed more quickly and safely by permitting a doctor to more clearly visualize the problem and be able to see exactly where he or she is working within the heart.

All surgeries and interventions at any age carry risks, as we know, and not everyone is a candidate for such interventions. And some are just lucky to go on without it, like Ron Gilbert.

Garnett Beckman

Like Garnett, many centenarians in our group have experienced a major medical problem in the decades leading up to 100, and often in their 90s. Yet they are reticent about discussing these challenges, and when asked will often say they don’t dwell on them once passed.

Lulu Johnson, 100, is a case in point. “I believe in being positive and I love being around people,” she begins. “She never complains,” her daughter says, “and she strives to be upbeat at all times.” But for Lulu, living to be 100 has been a series of challenges. “I’ve had to work at it,” she confides, when asked. Along with being a cancer survivor, she has had five stents in her heart in recent years, as well as a cornea transplant “so I could continue reading, which I’ve always loved to do.”

For Bernice Kelly, living to 100 has also been a challenge. “I enjoyed good health through my 60s,” she says. “I went to the doctor once a year for a checkup and was healthy until the age of 74, at which time I was diagnosed with breast cancer. I am a survivor. In 1988 I had gall bladder surgery, in 1992 colon cancer. I am a survivor. In 1995, I had my left hip replaced. In 1999 I had cataract surgery on both eyes. My right hip was replaced in 2001, and from 2005–2010, I had pneumonia and congestive heart failure; then came diabetes in 2007. In 2009, I began having mini-strokes (TIA). My family says I have been a trooper through all of this. I do not believe in complaining about my illnesses, I am just grateful to be alive. I am a survivor. I just celebrated my 100th on March 7th (2013).”

A minority of our group, however, say they have never had a serious medical problem, and the strongest medication they take is aspirin.

Looking for the Genie in the Genes

Irma Fisher Ferguson, 104, has special bragging rights: both she and her mother lived to be centenarians, her mother to age 102. “What is so unique, I think, is that I gave my mother, Rachel Fisher, a 100th, 101st, and 102nd birthday party with family and friends, beginning in 1968. Things were more subdued then, there wasn’t such a big occasion. But the whole town was impressed, of course, and happy for her. We had the party at home, with about 84 family—ranging from her children to great grandchildren—and friends, and served coffee and punch. But we did have a special cake; it was two tiers with 100 candles that was something to see. I never thought about living to be 100, but it’s wonderful. I feel fine.”

The Promise of Genetic Research

The potential results of genetic research are enormous and widespread. Currently, there are a number of research projects being conducted that are studying people 100 and over, looking at various aspects of centenarians’ lives and genetic makeup. In demand as research subjects, centenarians are playing an important role. As one remarked, “It seems like everyone wants a sample of my DNA. I hope they find something useful.”

In the very near future it is expected that definitive “longevity genes” will be identified, and that this knowledge will assist in developing new medicines and health methods to enhance longevity for us all.

Toward this end, a large research competition in 2013, the X-Prize, is being offered by the nonprofit foundation of the same name. The current prize in the Life Sciences category is $10 million for the team sequencing genomes of 100 centenarians with the most accuracy, shortest time, and lowest cost.

The Potential of Cancer Research

You would never know it to look at her, but like many of her centenarian peers, Lillian Cox, 106, is also a cancer survivor. “I was diagnosed with breast cancer in my early 90s,” Lillian tells. “At that time there weren’t many options and a lot of women still had mastectomies.” Today, there are much less drastic procedures, and cutting-edge research that aims to provide even less invasive and more effective treatment.

A “game changer” in cancer research has taken place in recent years, thanks to the development of high-speed computers and the further development of artificial intelligence, according to Dr. Ronald A. DePinho, president of MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. “We can now sequence genomes of the entire tumor profile in a few hours and analyze the data for a few hundred dollars thanks to advances in computing. This is allowing us to target treatment. Also, we are in the third generation of artificial intelligence, which is helping to not only analyze the data, but draw conclusions about treatment options. The development of medicines that will trigger the power of a person’s immune system is another recent advance in the treatment of cancer.”

Genomics and the ability to trigger the immune system seem to be working on parallel paths. “Through genomics, if they can figure out if there is a propensity to get cancer, they can trip the immune system to stop the cancer from growing,” Dr. DePinho explains. “This ability to trip the immune system may apply to other diseases that affect people in later years, such as Alzheimer’s, diabetes, and heart disease.”

The Fight for Sight

Deteriorating vision to the point of potential blindness is a risk as we age. Cataracts, glaucoma, macular degeneration, and other degenerative diseases challenge both the individual and medical experts alike.

Eleanor Harris

“Because of macular degeneration, I lost most of my eyesight when I was in my mid-90s,” Eleanor Harris, 100, begins. “It happened gradually; my eyesight got worse and worse. At first, I had a reading machine that I used to enlarge the print to project on a screen and that was wonderful. I would write letters, checks, and read the newspaper, but after four years, that no longer helped me. I could no longer see what was on the magnified screen. That was a blow. I gave my machine to the library in hopes that someone could use it, so I had to go at it alone. It has been stressful, but there’s one good thing: The doctors say with macular degeneration I will never be totally blind. I am taking comfort in that. Right now I can see forms and shapes, so I get around and I can see the white walls here at the retirement complex where I live in my own apartment. I take long walks every day and I can see people sitting or standing, but I can’t see their faces. Everyone knows when they come up to me to say their name and that’s how I know who they are.

“One of the hardest things in the morning is getting a shower and getting dressed. The walk-in shower here has bars to hold on to, so I feel safe. Getting clothes to match is a problem, getting the right pants and the right top. Sometimes I have problems distinguishing colors. I can see red, white, and yellow. That’s why they mark the curbs with yellow. That’s one color that’s easy to see. I have conquered the challenge of getting dressed. I put the entire outfit on one hanger—shirt, jacket, and pants. And every night when I get undressed I put it all back on the same hanger in the closet. There are always ways to get around your difficulties.

“Fortunately, I don’t need to see or read music to continue to play the piano, since I’ve been doing it for most of my life. My grandson says I play at nearly concert quality, but then, of course, he’s my grandson,” she says with a smile.

Continuing research looking to the development of gene therapy to combat degenerative eye diseases is being conducted at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary in Boston. The object of this research is to improve clinical genetic diagnosis and the identification of new “disease genes” and research directed toward state-of-the-art clinical care for patients with genetic vision disorders. The ultimate goal, of course, is to improve and possibly restore sight to those affected. A genomic laboratory to accomplish this work in ocular genomics, as the field is called, is being built (2012).

LIFESTYLE IMPROVEMENTS THROUGH TECHNOLOGY

Bill Gates, co-founder and chairman of Microsoft, has predicted that living conditions will dramatically improve over the next 20 years due to advances in technology. “The digital revolution is just at the beginning,” he said. “The pace of progress is more so than that in the 1980s when computer technology was in its infancy. Great work is being done in all the innovation sectors and at an amazing pace . . . in the lifestyle area, speech and visual recognition are improving, along with artificial intelligence.”

These predictions for what’s coming will make life easier as we age. What was once just imagined is becoming reality, for instance, the development of robots that can help around the house, bring objects to a person, and even do grocery shopping.

“I’d really like to have one of those robots,” said centenarian Art Fortier.

A new advance in computer technology for the average consumer uses eye movements to perform a number of functions on a personal computer. It combines eye gaze with other controls, such as touch, mouse, and keyboard. These products have the potential to make computers easier to use and may be especially helpful to older people. Early examples of this technology will be available in late 2013.

USING COMPUTERS, TABLETS, AND SMARTPHONES

When it comes to computers and other new technologies, such as smartphones, many centenarians are willing to learn but some find it difficult. Nonetheless, “most of those who are interested and persist will succeed,” Marvin Kneudson says confidently, obviously referring to himself as he answers a call on his cell phone during our interview.

“I use Skype to keep in touch with my grandsons, who live as far away as Alaska. It’s great—almost like being there because we can see each other. I think more seniors should get into it. It’s really easy once you get the hang of it—and it’s free!” says Marvin Kneudson, 100.

Marvin Kneudson

Centenarian Charles Kayhart agrees that older people can enjoy new technology, as he proudly displays his iPad. (See photo in Chapter 6.)

Bernice Kelly, 100, is being introduced to Skype by her family so she can keep in touch with family members who live out of state.

Still, not all centenarians are convinced that they need to have the latest “toys,” as some call them. Ruth Donaldson, who lives with her daughter near Marvin Kneudson, says, “I’d rather just pick up the phone, which I do often, and call my friends and relatives back East. I’m not into all these new electronics; they really blow my mind!”

LIFESTYLE CHOICES

When Elsa Hoffmann first learned that centenarians in other regions of the world were being studied, she said: “I don’t see why researchers have to go to isolated areas of the world to try and learn the lessons of living a long and good life when we have a much higher number of centenarians here in our country to learn from, and who are very good examples. To me, that would be more relevant.” (The exception is the Seventh-Day Adventist population, which is a group often studied, headquartered in Loma Linda, California. Elsa acknowledged that while it worked for them, it wasn’t for her.) Frustrated and in typical take-charge fashion, Elsa decided to write and publish her own book, with the help of her granddaughter, Sharon Textor-Black. On the cover is a picture of a smiling Elsa, dressed for a formal event and being carried in by a handsome young Chippendale. Elsa has a point: there are wonderful examples of living long and living well right here in America, and many are in this book.

Elsa holds firm on the examples of America’s centenarians as role models for the future of aging, adding, “You have to take into account a person’s circumstances. Not everyone is dealt the same hand in life. The trick is to do the best with what you have. Not everyone has the financial resources, and they do the best they can. Not everyone wants the limelight or to look outside their family for social activities; not everyone wants to make new friends or younger friends, and they are content to spend most of their time with family. Not everyone has family and, God bless them, they are making friends and making it on their own. There’s so much variety, but we all share one thing: we’ve made it to the century mark!”

THE BIG THREE

Along with the advances in medicine and scientific research leading to greater longevity, there is an increasing awareness of the importance that lifestyle choices play. Many centenarians are paying more attention to the role of diet, exercise, and socialization in making it to the century mark and often beyond.

Undoubtedly, there are some behaviors most of us can modify to help us live longer and healthier. We’re all aware of the importance of diet and exercise and have had it drummed into our popular culture since the 1970s. Perhaps we should revisit their importance in our lives as we look ahead to our later years.

In addition, the positive impact of socialization has been largely ignored until the past few years. Current studies confirm what every older person knows: it’s not healthy or happy to feel unwanted and marginalized in one’s later years. Being an integral part of our families, connecting with friends, and remaining involved and interested in our communities and the world around us contributes to longevity.

Thus, what we have learned from our centenarians is that over the decades leading up to the century mark, many began to pay more attention to the positive health styles that do seem to make a difference, intentionally doing all they could to improve their chances of living longer, and maintaining a good quality of life in their advanced years. They are no longer leaving it to “good genes” or “good luck.” It’s a reminder for those of us who wish to follow in our centenarians’ footsteps, to do the same.

HEALTHY DIET

What works for our centenarians seems to be moderation—an idea that has always been in fashion, for those who can do it. Our centenarians have had the discipline and wherewithal to live their lives accordingly. While some enjoy a glass of wine or a cocktail, they are quick to add that it is never in excess; while many say they do not follow a particular diet (such as vegetarianism), in general they are not big eaters and most are of average weight or less. Very few are obese, and none in our group.

Right-Sized, Not Super-Sized Meals

In 1960, when centenarians were in middle age, the average individual weighed 20 to 30 pounds less than those in their middle age today. While there are many different schools of thought on this increase, three factors seem to be most important. The introduction of high-sugar, high-fat fast foods and increased portion sizes—the more is better mentality—and less physical demand on an individual’s routine, as walking has been replaced by driving, housework has become easier, and the workplace has become more automated.

“The answer (to being overweight) to me is simple: downsize your supersize meals,” says Astrid Thoenig, 103.

“For those who recall the dinnerware and glasses of the 1950s and 60s, they were much smaller than their counterparts today. A dinner plate was closer in size to today’s salad plates, and wine glasses were a third of the size of those in use today. Take a look at your wedding china if you still have some; you’ll see what I mean. Instead of worrying about what diet to be on, why not just eat fewer calories. It works.”

Several studies are investigating the connection between calorie-restricted diets and longevity, with varied results. But this is not the extent to which our centenarians refer. In general, they will say: eat a balanced diet and eat sensibly. Besse Cooper, 116, the world’s oldest woman in 2012, advised, “Don’t eat junk food!” The majority of our centenarians share her view.

For Some, an Extreme Diet Is the Key

Some centenarians, like Bernando LaPallo, take a holistic approach to life. At 107, when we first met him, he looked and acted 30 years younger. “I believe in a raw food diet, much of the time; sometimes vegan, but nothing beyond vegetarian,” he reports. “I’ve been eating like this for most of my life.”

Bernando LaPallo

Bernando also believes in the importance of dietary supplements to help him remain healthy and vital. If anything, he seems more active two years later at 109 than ever. In the interim, he’s written a book, Age Less/Live More: Achieving Health and Vitality at 107 and Beyond, and is working on another. He gives talks on the benefits of a vegan/vegetarian diet, and has an active web site maintained to spread his message. His vitality is amazing.

Heart-Healthy Diet

For people who have heart disease, recent research shows that a heart-healthy diet can make a world of difference, even in later years.

Former President Bill Clinton, for one, has been outspoken about his change to a low-fat, primarily vegan diet. Proponents of a vegan or vegetarian diet say it helps with weight loss, is anti-inflammatory, and beneficial in lowering cholesterol and blood pressure.

A recent large-scale international study was conducted to assess the benefits of a heart healthy diet. There were 31,546 adults ages 55 and over in 14 countries, enrolled in two separate clinical trials of blood pressure–lowering medications. These subjects were considered high risk for heart attack, stroke, or other heart-related problems and were shown to have significantly benefitted from a heart healthy diet with an emphasis on eating fruits and vegetables, fish, and nuts. Mahshid Dehghan, PhD, a research associate at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, said, “Many people with heart disease may be under the mistaken impression that taking their medication is enough to reduce their risk.”

In early 2013, the New England Journal of Medicine reported on a large-scale study showing that a so-called Mediterranean diet, featuring the use of olive oil and nuts, along with fruits, vegetables, eggs, dark chocolate, whole-grain cereals, fish and white meat skinless chicken and turkey, reduced the incidence of heart disease.

Maurine Furney, 100, says, “My lifelong emphasis on good nutrition has contributed to excellent health and an active centenarian lifestyle.”

Maurine lives independently and recently attended a high school alumni get-together. “Of course, I was the oldest one there.”

The Seventh-day Adventist Diet

Dr. Frank Shearer

Dr. Frank Shearer, 105, points to the studies conducted on the lifestyle of Seventh-day Adventists by Loma Linda University in California, his alma mater. “It has been found that those who follow the Seventh-day Adventist lifestyle live several years longer than the average American.

“We eat only a vegetarian or a vegan diet, and are strict about taking our Sabbath (Saturday) as a day of rest and renewal, faith, and prayer. I think the day of rest and a break from everyday stresses is as important as the diet. We also believe in keeping physically active. However, younger members are not as strictly adhering to this regimented diet, so we’ll see if that makes a difference.”

Dr. Shearer practiced medicine as a country doctor for 50-plus years. During these years he found time for horseback riding, camping, fishing, flying (as a private pilot), and water skiing, a sport he took up in the 1930s and still enjoys on occasion.

THE BENEFITS OF EXERCISE

When it comes to exercise, despite what is now known about its importance in contributing to good health, there is no consistency among our centenarians. However, we have found they are trending toward the contemporary view that exercise is important to health and vitality. More centenarians are exercising, even if they began later in life. Of the late bloomers, around age 75 seems the mean, and they continue to do so. As Louise Calder, 100, says, “I don’t leave my bedroom each morning—not even for breakfast—until I’ve done my half-hour of stretches” (later she walks at least a half-mile). Centenarians are “hitting the gym,” too, and engaging in strength and resistance training, along with the stationary bike; many have them at home. The treadmill is the one exercise device they shy away from. An established and frequently referenced study at Tufts University in Boston has found that older people, even those 100 and over, can benefit from strength training.

The late Dr. Robert Butler, known as the father of geriatric medicine, said as far back as the 1980s: “If there were only one prescription I could give to my patients it would be to exercise.”

Katherine “Kit” Abrahamson—Dancing at 80 and Beyond

Katherine “Kit” Abrahamson took up dancing when she turned 80 and continued until six months before her 105th birthday. Her favorite dance is tap but the group she belongs to, The Cape Ann Seniorettes, specializes in line dancing. Kit believes the twice-weekly dance lessons for over two decades have kept her agile and healthy, and certainly happier.

A lifelong resident of Gloucester, Massachusetts, Kit is one of 14 children from a close-knit Irish family. “I’ve learned that family is very important, of course, but you also need to have outside friends, or you’ll be boring. My best friend is a member of our dance group in her 80s. She’s tall, I’m short; of course, they call us Mutt and Jeff, but we don’t mind—it’s all in good fun.” Kit admits to still getting stage fright even after 20-plus years of recitals. “Once a year we have a large recital and everyone’s family comes, of course, and so do lots of town folks. And every year I have butterflies in my stomach, afraid I’ll forget a step, but I never do. I guess it keeps me on my toes, so to speak. My great granddaughter Katie—my namesake—took up dancing when she was 10. She began taking dance lessons at the same studio I go to, and she learned the line dance steps. She looked so cute in her cowgirl boots and hat, and we danced together for several years at recitals. We were quite a team, just 90 years apart!

“Our dance group performs at events in the area and community events and at retirement homes. Most of the residents there are younger than I am.”

George Blevins—Kegling Champ

George Blevins is a bowling champion at age 100. He is a regular participant at the National Senior Games and the only 100-year-old bowler in the over 75 class. George has won two national bowling singles tournaments. He is one of two centenarians regularly participating in the games (the other is John Donnelly, the table tennis champ). George also competes in the Indiana State Senior Singles Tournament.

Attracted to bowling at the early age of seven, George continued to bowl while an industrial engineering student at Purdue University, as well as during his long career as a special assignment engineer for International Harvester. “One year I was the captain of five different teams,” he says proudly. “But some years I had trouble making it back home to stay active on any team, and I really missed it. I traveled a lot for my work, driving all over Indiana. When I retired, I took up bowling full time. I love it.

“In my early days we had natural wood lanes and pins. Oil patterns made it difficult to keep the ball on a line to the pocket. ‘Pin stickers’ labored for 10 cents a game, picking up the pins and resetting them for the next shot. It was hard work. Score keeping was done by hand using pencils on large sheets of paper. It was not like using the modern automatic score keepers of today. I learned to add the score in my head.

“I never thought about living to 100. No one in my family lived particularly long that I knew of. I thought of myself as just an average guy. Then, when I was in my 90s, I continued bowling, being active, and living on my own.

George Blevins

“I realized that I was doing more than most 90-year-olds do ordinarily, so I started to think of myself as something special, and then I hit 100—wow!”

“I still drive and bowl two to three times a week. I bowl in a league on Monday and practice on Wednesday and Thursday.” George credits “clean living and a steady diet of 10 pins” for at least part of his longevity and robust health. “The rest is a mystery,” he says. “But I’ll take it.”

Elmer Askwith

A few centenarians, Elmer Askwith for one, still grow their own vegetables and at the same time get vigorous exercise. Elmer is very proud of his large garden and says, “I’ve been duking it out with the clay soil of northern Michigan for over 60 years.” To do so, he has created his own composting system and nourishes his soil each year. “I’ve rigged a composter to do it.”

Elmer says he has always been industrious and inventive in a practical way. He lives alone in the house he built for himself and his wife many years ago, and until recently heated only by a wood stove, with wood he carried in himself. “I made a special backpack as I got older so I could carry it easier,” he tells. Elmer enjoys building and fixing things, and finding ways around everyday challenges. It’s a trait he developed long ago and it has served him well over the years.

“I was born on a farm in upper Michigan in 1911,” Elmer begins. “Like our neighbors, our family was long on love and short on cash. We didn’t have two pennies to rub together. When I was seven, I decided I wanted a violin. My father agreed, so long as I earned the $7 it would cost to order it from the Sears and Roebuck catalog, as most everyone did in those days. They carried everything from toys to clothes and washing machines—heck, you could even buy a house from the catalog and put it up yourself. I knew people who did that.

“Anyway, I found out that the township was paying 10 cents, a princely sum, each for a rat tail, as a means of holding down the rat population in the area. So I tried various methods of catching them, with little success.

“Then one day I decided to build a trap using the rain barrel—cut a hole in the top, put a few kernels of corn on the lid, and when the rat came for them, he fell into the barrel and drowned.

“Pretty soon I had my violin, and after torturous practice (my father said it almost killed him) became so good at it that by high school I started a band. We played school dances, at church functions, sometimes in people’s homes at parties. We played the fox trot, waltzes, and square dances; it’s how I met my wife. People would come from as far away as 20 miles to hear us play and dance to our music—we were that good!

“We married in 1932 during the Depression. It was awful. Men would do about anything to get work. I was lucky to get a job as a fire ranger and spent six summers, 10 hours a day, 7 days a week, sitting atop a 40-foot fire tower with binoculars, waiting to report a fire, which a lot of the time I did. But much of the time was just sitting. I would play my violin, but I also started designing my future home.

“Eventually, I got a job at the Sault Ste. Marie locks and worked there for 35 years, retiring as a lock master.

“When I could finally afford to build our home, I bought 10 acres from the township and dug the basement myself in the same hard clay. I dug it by hand, sometimes using a sledgehammer to break up the clay. There were many delays, and I had to try three times because the rain would keep washing in the hole. It wasn’t until after the cement was poured that I noticed that the hole wasn’t square—so I built a crooked house to fit it.

“The most frustrating point in my life came shortly after the house was finished. No sooner had we moved in when the town came to me and said they needed part of my land to build a schoolhouse. Unfortunately, the part they wanted was where I had just built the house! So I had to dig another basement down the road, and then rig up logs to move the house on. I did, and I’m still living here today.”

Elmer Askwith

Maintaining Independence

A surprising number of centenarians in our group live independently. About 35 percent live either in their own home or apartment or in an apartment in a retirement center. Most were rightfully pleased to be doing their own housework, which they count as exercise, and of taking care of themselves.

Mattie Bell Robinson, 100, says, “I continue to live independently in my own home and I still plant a garden and can food for the winter months.”

Mental Exercise

In addition to staying physically active, our centenarians are acutely aware of the importance of keeping their minds active. Ron Gilbert plays bridge, as do many others; Louise Brooks loves crossword puzzles, another popular mental exercise; and most read the newspaper daily. Others pursue hobbies, including artwork and crafts, like Bonnie Hernandez, who loves to crochet. And, of course, there are the techies who love using their computers, e-mail, smartphones, and iPads. Some are still taking classes at local colleges, community colleges, at their senior centers, retirement homes, and churches.

“My husband and I performed at the Metropolitan Opera as supernumeraries (extras) for over 50 years. I still live in New York and my current hobbies include 300-plus piece puzzles and working on my iPad,” says Kitty Slesinger, 100.

Stay Sharp, Stay Young

Dr. Herbert Bauer, 102, has been known to read an entire book almost every day. “He’s incredible,” a friend says. “He’s kept on learning throughout his life.” When asked what has been his key to success through a lot of different times and difficult circumstances, the resourceful centenarian credits persistence and a positive attitude.

A few days after completing his medical degree in Vienna, Austria, in 1936, Dr. Bauer abruptly left the country just after the Nazi invasion. “I escaped by jumping out a window just as the Nazis were pounding on the front door. That was the only way to get out alive, and I had the worst possible classification: Liberal!

“I spent a few years in England before coming to America in 1940,” he tells. While in London Dr. Bauer helped find jobs for people who escaped from German-occupied countries, and met his wife, Hanna, in the process. They settled in California, in the San Francisco area, where Dr. Bauer finished his medical internship while working as a nursing assistant. “You do what you have to do,” he says pragmatically. Dr. Bauer started a public health career about 70 years ago near Sacramento, and served as Yolo County’s public health director from 1952 to 1971. He is credited with having created the health department there. “I started it from the ground up—I knew I could make something of it.” The desire to help the underserved and underprivileged has been a central tenet of his life.

“I even have a new building named after me. The Herbert Bauer M.D. Health and Alcohol, Drug & Mental Health Building, located in Woodland, California, the capital of Yolo, County.”

“The supervisors told me this is the second-largest building in Woodland,” Dr. Bauer said. “The biggest is the county jail. I’m No. 2.”

Later, he joined the faculty at the University of California, Davis Medical School, as a Clinical Professor and has continued lecturing there from time to time since retirement and even after becoming a centenarian.

Over the years, Dr. Bauer improved his academic credentials by adding a master’s degree in public health from the University of California at Berkeley, and, at the age of 61, a child psychiatry certification from UC Davis. (His wife was a clinical psychologist.)

He has enjoyed an active retirement. At age 99, Dr. Bauer traveled to Europe, including a river cruise on the Danube. “I stayed a short time in Vienna, where I visited the house in which I was born. It was still standing there and the window through which I escaped was open. The people I met in Austria were quite friendly but seemed unaware of their past history. For instance, they took me to the high school from which I graduated and asked me what I remembered. Wanting to be as kind to them as they were to me, I did not tell them that during the years prior to the German invasion, the Nazi party had been active in their country. Nor did I tell them that what I remembered from high school was the Nazis coming in and beating us out of the classroom. What I really enjoyed in Vienna, then and always, was their glorious music, their Alps, and their Apfelstrudel. Don’t tell me I am not fair!

“I have always stayed active in local health committees,” he said. At 99, “I took up dance, joining the dance theater in Davis. I also taught a course at a lifelong learning center, Sex and the Law.”

About growing older, Dr. Bauer advises maintaining an active social life. “It is important as we age. I don’t think there has to be a cutoff—at 65 you’re old. You’re not old. Continue doing things you enjoy and are interested in throughout your life, no matter what your age, both in your personal relationships and avocation. Keep trying new things that interest you. Life isn’t over; do something else that uses your talents after you retire from your main work, but plan ahead. Don’t just wake up one day and say, ‘What am I going to do now?’”

Dr. Bauer continues to live in his home, has a multitude of friends, and swims “most days” in his pool.

SOCIALIZATION AND QUALITY OF LIFE

“Social gatherings and a good sense of humor have helped me live to 100,” says Winnie Harmon, 100.

As mentioned earlier, socialization is one of the three components to a healthy lifestyle, along with diet and exercise, that contribute to a good quality of life in later years. As we are reminded by our centenarians, it’s not just how long we live that matters, but also how well. The examples of how they continue to interact with family, friends, and their communities show us that achieving a good quality of life in later years is possible. And it is never too late for romance.

Numerous studies have confirmed what our centenarian experts say: that socialization is as important to maintaining health and a good quality of life in advanced years as are diet and exercise. The feelings of loneliness and isolation are the culprits, it seems, that rob an elder of feeling well; not the physical act of living alone, as many family members and social workers fear. In fact, a Harvard study posits that an 80-year-old living alone might be stronger and healthier than someone of the same age who can’t manage on their own.

Clarence Weinandy, 100, who is known as Andy, can attest to this. “I live alone in a close-knit neighborhood in Florida,” he says, “but I’m never lonely. My neighbors are my friends. They look in on me, keep tabs on me; we go out together, they invite me to dinner . . . they’re terrific. I was born and raised in Ohio. My mother was very strict but loving. She had several basic rules that she pounded into me. One was: ‘A person who can’t amuse himself is poor company for others.’”

Social Networking

The era of the computer, cell phones, and now smartphones, Facebook, and Twitter allow older adults to keep pace with contemporary life and be involved with each other, staying up to date with current events, making new friends, and continuing contact with multiple generations in their families. These devices help overcome not only social barriers but physical impediments, distances, inclement weather, and not driving. They also help manage financial tasks for those who have learned to use them, in general making life easier.

At 100, Miriam Samson says she is “active on the computer to be current with the changes in technology.” She’s experimenting with making new friends using social media, but relies mostly on e-mail for writing to her friends. “I even send condolence letters now by e-mail,” she says.

Some centenarians who were users of computers in their 80s and 90s have chosen to help share their knowledge with their peers. Centenarian Bill Miller began using a computer at age 89, given to him by his sons. He was then left to his own devices to learn. “I found a new direction in life,” he says. “Once proficient, Bill volunteered at the local library and taught seniors how to use the computer and navigate the Internet. He has been recognized by the Baltimore County Public Library for his years of dedicated service.

At the age of 99, then a widower, he met a special friend, Jeanne, “who has given me a new spirit and meaning to my life,” he says. Valentine’s Day is their favorite celebration. Bill enjoys mathematical games and tricks, which he likes to play on his friends. What keeps him young at heart, he believes, is his interest in continuing to learn new things.

With his zest for life and contemporary view, Bill says “I am happy being a good example to my two sons, five grandchildren, and three great grandchildren.”

Not surprisingly, recent centenarians are more likely to be interested in learning and using technology. Walter Kistler, 100, says “I do everything on my computer including making greeting cards. My wife Sally, who is 98, also has her own computer and enjoys corresponding via email.”

Others, as with Bill Miller, have been using computers for several years leading up to the century mark. And for some centenarians, like Verla Morris, the burgeoning use of technology in their careers has made them more inclined to keep current with its use after they retired.

Love and Relationships

Some people find it surprising that in later years romance still blooms and may be amazed to see couples in their 70s and over on a romantic first date. What we’ve learned from centenarians is that people don’t outgrow their desire for love and companionship. There are numerous examples of second or even third marriages occurring later in life—70s, 80s, and 90s—such as John and Marian Donnelly, and Don and Kay Lyon. Yet some centenarians, such as Will and Lois Clark, and Jon and Ann Betar, are still married to their original spouses (for 75 years or more).

Bess Pettycrew and Paul Olson

For Bess Pettycrew, 101, meeting Paul Olson, 103, “is the best part of being a centenarian.”

Bess was living in a retirement center in the Midwest town near where she was born and raised. Paul had been living on his family farm, which he’d been running all his life. After losing his wife, he decided to move into town to an apartment at the active retirement community. “On the first day there, I was shown to a dining table and introduced to a few of the other residents. I was seated next to a woman by the name of Bess. We soon discovered we had gone to high schools in neighboring towns and that she had graduated just a couple of years after I did in 1925. We struck up a conversation and have been together every day since,” he says with a broad smile. “It’s nice when you find someone who grew up in similar circumstances and around your own age. We have a lot in common.”

Paul began playing the saxophone and played in the school band and in a dance band with some friends. Later, he also played sax in the town band and a few more local dance bands over the years. “I was never good enough to play professionally,” he says, candidly. “I don’t know why we never met earlier,” Bess muses. “I went to many of those functions.”

Paul has continued playing with a group of friends at the retirement center in what they call the Just for Fun Band. “Most of the other members are 20 years younger. We entertain regularly at nursing homes in the area and, of course, play for dances and functions at our retirement center. People really enjoy the old tunes, the ones they grew up with, and I remember them all.” But he is quick to add, “Our playlist also includes more current favorites, too.”

“I like his music,” Bess adds. “He makes things a lot of fun.”

Paul Olson

Betty Lucarelli

“After I was widowed in my late 70s, my cousin invited me to come to Florida to visit and escape the New Jersey winter. He lived in an apartment in a large retirement community that had guest rooms for visitors. On the first day, we went to play golf, and he had a friend with him from Ohio, who had also been invited to visit and was staying with him in his apartment, unbeknownst to me.

“We played nine holes and had a pleasant time, and I didn’t think anything more of it. Later that afternoon I was invited down to his apartment for cocktails, and there was Ernst again. We had more of a chance to talk and get to know each other. I learned that he had recently lost his wife. The more we talked, the more we found we had a lot in common—we were of the same Italian heritage, the same religion, and liked many of the same activities. And Ernst enjoyed good food—and I’m a good cook!

“The next day he asked me out for dinner and we talked some more—and kept on talking. By the end of my two-week visit, we had decided that he would come home with me to New Jersey. He met my kids and my friends; within a few months he sold his home and we married and lived in my home in New Jersey. The next year, we decided to move permanently to Florida.

“We bought a home and made new friends. (Ernst is five years younger.) We love to dance, go out, entertain, and we have traveled worldwide. On Sundays, I pick up a friend who doesn’t drive and we go to church in the morning; Ernst has some ‘quiet time’ to read the papers. When I come home, I prepare a big Italian meal (although I admit I do use jarred sauce now, but I doctor it up). Then friends and neighbors drop by for dinner—they don’t need special invitations. Anyone who wants to can come. We have a full house and a lot of fun.”

Ernst adds, “Betty does all the cooking. You don’t mess with Betty in the kitchen. That’s her domain.”

“We have a good life,” Betty concludes. “I never thought I’d be so happy again.”

Relationships with Friends

For Helen King, 100, belonging to the Red Hat Society and staying active in their many events and functions provides an active social life. “The Red Hat Society is one of the largest social organizations in the world, with chapters everywhere. Unlike some organizations for women, there are a lot of older women here and age is not a barrier. In fact, it’s encouraged,” she says.

For others, such as Lillian Cox, it’s belonging to the garden club and other traditional women’s organizations. Marion Rising, 101, says “I enjoy playing word and board games, being with friends, and doing my volunteer work.”

Teddy Schalow is a fixture at her local senior center, which she helped to found many years ago when she moved to Arizona from New York. “They needed a lot of things here; it was pretty quiet. So I thought I’d liven it up a bit. After we got the space and had the center up and running, I began organizing parties for every possible occasion—we had dances, buffets, brunches, movies, you name it.” She volunteered into her mid–90s. “Now I come and let them wait on me,” she says good-naturedly. “Everybody knows me here. They come up and give me hugs. It makes my day. Everybody should have a hug now and then.”

Teddy still drives her car to the center, smartly dressed and wearing her trademark heels. “You’ll never catch me in flat shoes,” she says as she opens her closet door to display at least 40 pairs of midsize heeled pumps. “Not even around the house.”

For Maynard White, 101, who lives with his daughter in her home, it’s the senior center and his church that provide outside socialization. “I don’t want to sit around the house all day,” he says. “I feel the church has, in particular, given me a desire to help people in times of need, and I try to contribute my time to them. It’s a good foundation for living a good life, and I enjoy the people there.”

Teddy Schalow

For Dick Morris, 102, fraternizing with friends at the retirement center where he lives in his own apartment has kept him socially engaged. “I go along on all the outings and help the activities director with the people in wheelchairs, getting them in the van, pushing them in restaurants, the mall, the movie theatre—we go a lot of places, and I want to make sure as many people can come along as possible. I help stow the wheelchairs in the hold if we are taking a bus excursion.”

Dick was born and raised in Emporia, Kansas, and spent his formative years on the family farm. As a teenager he longed for adventure and worked for a year painting houses and saving his money. “By 19, I wanted to see mountains and the ocean—something more than the flat plains of Kansas. I traveled with a friend. When we got to Colorado we decided to keep on going and made our way to San Francisco. I loved the beauty of the West. We looked for work all along the coast, down to Los Angeles. Finally, as luck would have it, we ended up in Seattle where I got a job at the Fisher Flour Mill on Harbor Island. I stayed there for over 20 years. I married the widow of one of my good friends at the mill; she had a son and a large extended family in the area. They became my family.

“In 1941, we bought our first house and later sold it and bought a four-unit apartment building. In 1950, I quit the mill and bought a 65-acre resort on the waterfront. My wife, Alice, was the greatest business partner a man could ask for. For us, the resort was nonstop work. After 10 years, we’d had enough. We sold it and bought a house, fixed it up, and sold it in three months. That was successful, so we kept on doing it—buying fixer-uppers and selling them. That started my new career in real estate, which lasted 17 years. At 65 I decided it was time to learn to play golf, and we bought a mobile home and became snowbirds in Arizona and Southern California. It was a good life; in summer months we continued in real estate.” Dick’s motto is: “Learn to be contented, but never satisfied. In other words, never settle—always strive for improvement.”

Volunteer Work and Community Service

With or without family members for companionship, staying active in a worthwhile cause can bring a sense of purpose and camaraderie. Centenarian Martha Harrison, for example, spends her time knitting caps for premature babies at a local hospital, although she’s never had children of her own. “So far, I’ve made 1,400, and the hospital gave me a plaque for my volunteer work. Whenever there is a new baby on the way in my family—my nieces’ and nephews’ children—I start knitting. It’s nice nowadays because you get to know if it’s a boy or girl in advance. I used to make a lot of yellow caps and bassinet blankets.”

Miriam Krotzner

Miriam Krotzner, 100, of Prescott, Arizona, begins by saying, “I’m alone in the world except for my church and my friends.” Miriam and her first husband did not have children, and he died many years ago. Miriam has been on her own, living in her home, driving her car, and taking care of herself for a long time. Originally from Phoenix, she and her husband married at the age of 22 and ran a gas station and a small general store on the western outskirts of Phoenix. “We were like what would now be thought of as a convenience store,” she says in her chipper, upbeat way. “We lived in a small house across the street. It was his family’s business, and he was supporting his widowed mother and nine younger siblings.” When her husband became ill and could no longer work, she took a job at a “dime store” and enrolled in classes at a local college, “mostly typing and bookkeeping,” Miriam says.

After a three-year illness, her husband succumbed to tuberculosis. Miriam took an office job in Phoenix, where she met her second husband. They moved to Seattle, where she worked for many years for Northwest Airlines as a reservationist. “I was using one of the earliest computers,” she recounts. “It really was a new field, as was the entire reservation industry. It was exciting. I loved living in Seattle.” However, after her husband retired, they moved back to Arizona, to Prescott, for his health, which had been compromised by injuries sustained during World War II. Miriam was again widowed in 1990.

Miriam began volunteering at the VA hospital in Prescott, where long after retirement age she remains active. She also became very involved in her church and attends weekly Bible studies. “This is important to me,” she says. “It’s important to make friends—especially younger friends—when you’re alone and older. My friends are all 20 or more years younger, but they treat me as their equal.” Miriam is friendly, witty, and thinks and speaks at lightning speed. She also has a wonderful recall of people she’s met.

“I have read the Bible entirely through three times,” she says. “You need to keep re-reading it and studying because you can’t remember all that’s there.” Miriam says she reads several passages and special prayers each day, saying that it grounds her. “Some days, I read more.”

At 96, she fell on New Year’s Eve. “I was getting out of my car at the VA to go in to help serve a special dinner to the residents, and I slipped on the ice. I was rushing. I broke my hip, and it’s bothered me ever since, so now I use a cane for support, but I keep going!”

Never one to dwell on the negative, she counters brightly. “Did you know that Genesis 6:3 tells us that God has intended us to live for 120 years? I believe it.”

Mr. D

For Fermin Montes de Oca, 105, doing for others brings him a sense of satisfaction. In his full life, he has always found time for volunteering, but nothing has meant more to him than the Country Store he opened and runs at the retirement center where he has lived for several years in Florida. His store provides some necessities and lots of treats for the residents, including his very popular Mr. D’s Popcorn. For years, he has risen each morning at 4:30 to make the fresh popcorn to sell during the day at his store, which is staffed with other volunteers. At the end of each day, he gives the proceeds of the store’s sales to the hospice workers to buy things to help people in need.

“The people depend on me,” he says of his rigorous schedule. It was even difficult to get him to take time off to celebrate his 105th birthday. When asked, he can’t explain his desire to help others. He says he’s always been this way.

Born in Tampa, Florida, he and his older brother went to work when he was 10, shining shoes outside a cigar factory. They charged a nickel for black shoes and a dime for brown. After shinning 12 to 15 pairs of shoes, young Fermin would race home and proudly give all of his earnings to his mother.

When he was 15, his father moved the family back to his native Cuba and Fermin went to work for a cigar factory. He met the love of his life at an early age, and they were married for 76 years. They moved to New York, where Fermin got a job as a barber at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel. Gary Cooper became one of his regular customers and they developed a rapport. Cooper nicknamed him “Shorty.”

Eventually, he and his wife moved back to Florida, where “we had two sons, built a house, and lived happily,” he says. “I went to work for a cigar factory and stayed for 39 years, but I never smoked a cigar or cigarette.”

Joe Stonis

Joe Stonis, 100, is a man who was ahead of his time in Florida when he retired there over 30 years ago with his second wife, Doris. His chosen area, he recalls, “looked like a desert when I first saw it. I first noticed the ugly terrain from the plane, and by the time we landed I had decided that if this was going to be where I would spend the rest of my life, I had to do something to improve it!” Improve it he did, by becoming an advocate for green space and beautification. He turned the barren landscape into what is now a lush town on the Gulf Coast.

Born in Newark, New Jersey, with a career in the chemical industry, Joe had lived in several parts of the country, “wherever they sent me,” he says. “I had no experience in landscaping, but I began planting trees, so much so that I became known locally as the ‘tree man.’”

Joe began several civic initiatives to plant trees, to landscape the area, and eventually to advocate against the encroaching development in favor of a balance of green space. He has been spectacularly successful in his pursuit to bring green, beautiful open space to his corner of paradise. “If there’s a tree being planted here, I’ve likely had something to do with it,” he says proudly. Over the years, the trees Joe had planted initially have matured and it all looks natural now, “like it’s always been here,” he says. And that’s just the way he likes it. “But I don’t stop. I’m always coming up with something new to add to the beauty of this place.” Joe’s energy is amazing!

Others have recognized that these trees and greenery didn’t just happen by themselves, and Joe has received numerous honors from the community and the state. At age 91, he was the oldest recipient of the National Arbor Day Foundation award for his work at the community level. He adds this to his array of trophies won for his hobby: fishing, both fresh and saltwater. And along the way he’s written a book called Slices of American Pie, which he published at age 98. He’s now at work on another.

Joe is a wonderful example of the rich opportunities that can await a person in his or her retirement years. “Before I moved here, I never gave a thought to trees,” he says. “It just suddenly came to me that I have to do this. It’s really kept me going, interested and involved in the community and in other people.”

Joe Stonis

THE IMPORTANCE OF FAMILY

All centenarians who enjoy the closeness and attention of family rave about the difference it makes in their lives. They love being in touch with younger generations, watching them grow and have children of their own. As Pauline Copeland, 100, says, “We have five generations of Copelands now. It’s wonderful to watch them grow and to be surrounded by my children and their spouses, my grandchildren and their spouses, great grandchildren, and great great grandchildren. We often all get together and sing and just have a good time. Of course, I miss my husband Dewey and my beloved son Albert not being here to share in these joyous times.”

“I have made my family the most important thing in my life by showering all of them with love and respect and most of all the best homemade baked goodies and food!” says Esther Laufer, 100.

Centenarians who are considered the matriarchs or patriarchs in their families derive a sense of fulfillment and satisfaction from their role. They consider it an important responsibility to pass on their wisdom, knowledge, and family history to their descendants, either through written memoirs or stories and oral histories they share.

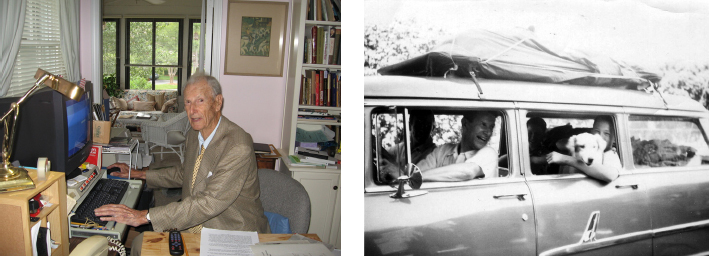

Karl Drew Hartzell

Karl Drew Hartzell, PhD, has had a long and distinguished career as a successful and respected professor, dean, and administrator in higher educational institutions. He also held a high-level administrative position at the prestigious Brookhaven National Laboratory. During WWII, he was appointed to the New York State War Council. Karl has lived the life of a brilliant intellectual, and continues to do so at age 102.

But it is not his impressive career or his many accomplishments—or even his current active lifestyle—that matters most to him. “Being a devoted father is my greatest role in life,” he says. “I credit my three sons for my longevity. Having children who are active and make it possible to think with them as they face their own evolving life concerns has been a factor in the quality of my life. My three boys and I have remained close. I travel (from his home in Florida) to visit them often (in the Northeast).

“I lost my father at the age of 10; he was a minister in the Methodist church. We moved to Massachusetts from California to live with my mother’s parents; she never remarried. Thus, my grandfather became the central father figure in my life. Were it not for him, I think I would have followed my father’s side of the family into the ministry. Both sides of my family were religious refugees to America: my mother’s family, the Drews, arrived in Plymouth, Massachusetts, in 1640; the Hartzells arrived in Pennsylvania near Philadelphia around 1730. I remain keenly interested in the study of religion to this day.

“My grandfather was a Boston lawyer, and he encouraged me in another direction. It was his view that to succeed in life I needed to excel at academics. I attended Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut, made Phi Beta Kappa (I was the only one with three athletic letters to do so—tennis was my best sport, and I was captain of the tennis team), and went on to Harvard graduate school for my PhD in history. It was his financial support, as well, that allowed me to do this. I finally graduated in 1934 and pursued a career in higher education. I met my wife while at Harvard. It was the height of the Great Depression, and she would only agree to marry me if I had a job. So I took the first one I could get. Summing up my life, I would say the best part is that I had a lovely family and an interesting career. I am at work now on my memoirs I want to leave for my sons: it’s titled The Laws of Living. So far it’s quite lengthy.”

Karl Hartzell, PhD

Louise Brooks—Matriarch

“As the firstborn of five children, I’ve been working every day since I was seven years old,” Louise, 101, often reminds her children, grandchildren, great grandchildren, and great great grandchildren. “My mother and father both worked and I had to stay home taking care of my sick grandmother and my younger brothers and sisters. I would put the dinner on and would have to stand on a box to reach the stove. I never had much of a childhood at all, so I enjoy watching all these kids get started.”

Known as a feisty, courageous, energetic woman, “I say what I mean and mean what I say. I’m not afraid to speak my mind if I feel someone is out of line.” Her granddaughter, Tonya, adds that she is both deeply loved and widely feared. “She’s quick-witted and can still tell you off six ways to Sunday in the blink of an eye.”

Louise says she has been blessed not only with long life, but also good health, having never been in a hospital until her mid-90s. “I get around just fine and enjoy reading and doing crossword and number puzzles,” she says, “and, of course, keeping an eye on all these kids. On occasion, I still bake biscuits—they all love ’em.”

Tonya adds, “Grandma is a matriarch who loves us all with a fierceness that only a mother can. We are proud of her and we love her because as the foundation of our family, the pillar upon which we stand, she has helped make us who we are today.”

Helen Haffner, aka “Aunt Honey”

Helen Wright Haffner was born August 12, 1912, in Lapidum, Maryland, where she has lived all her life. Her memory is “clear as a bell,” she asserts, and she remembers all the way back to her childhood. One of the stories she likes to tell is when she and her sister were “sky watchers” during WWII, as members of a civilian group called the Ground Observer Corps. They watched with binoculars for German submarines and ships from the Eastern Shore of Maryland. Describing herself as a “true Marylander,” she loves steamed crab and is a diehard fan of the Baltimore Orioles. “My favorite color is red.”

Most of her married years were spent as a housewife, but when widowed she worked in a vegetable packing house and in a local commercial laundry. A longtime partnership followed, but again, she was left alone. She enjoys playing bingo and cards and belongs to both the local VFW and American Legion.

Helen got her nickname “Aunt Honey” from one of her sister’s daughters who when young could not pronounce “Helen,” and instead said “Honey.” “The name stuck,” her niece Debbie says, “because it fit her so well.” Described as always a happy and positive person, although she had no children of her own, all of her nieces and nephews and their children are her children and grandchildren, the family tells. For many years, she has been the “reigning matriarch” of the family, all of whom live nearby and visit often, helping with household chores and grocery shopping, so she can maintain the independence she loves.

“In the evening, I enjoy a nip of blackberry brandy, and sometimes a Rolling Rock beer. My grandnephews will stop by and we’ll crack one open and have a chat and a good laugh.”

Juanita Redpath

“When my husband and I divorced several years ago, I lost him but kept his mother,” Nancy begins. “My mother-in-law, Juanita, 101, and I have always been close. Now we live together, travel together, and have a good time. She’s an amazing woman. Lately, we’ve been traveling around the country by car, visiting some of her surviving family members, especially her younger cousins. She enjoys getting together with them and sharing family memories. It’s amazing, though, the different perceptions people can have in the same family. Sometimes we’ll get in the car to leave and she’ll say to me, ‘He has that all wrong. That’s not what happened.’ It’s cute,” Nancy says. “As the oldest in the family, she’s convinced she knows best.”

One of Juanita’s happiest memories was when she and her five siblings and parents, with all of their belongings, drove in a Model T Ford from Springfield, Illinois, to live in Southern California, camping along the way. “Sometimes we would be lucky and make 100 miles a day,” she recalls. “At night we would set up a big canvas tent and cookstove. We kids—the oldest was 14, I was nine—thought it was great fun, but I’m not sure my parents did. When we got to California, relatives who had moved there before us would take one of us in. We were parceled out for a time; sometimes we would live in the tent. It was a few years until my father could build us a home.”

“Nita,” as she’s called, only finished the eighth grade, but says she has never lost her interest in learning. “I was always a reader and loved the library. I like bird books and bird watching, flower books to help with my garden, which I still maintain, and tour guides to read about places I’d like to see. I met my first husband at an open-air dance hall when I was just 16. We married that same year, and our first son was born when I was 17. We had two more children and then divorced. I married my second husband right after the war and we had a son together, the one Nancy was married to. I’ve seen a lot in my life, from ice deliveries by wagon to the age of electronics, from cod liver oil treatments to heart transplants. It’s been a wonderful life.”

INTERESTS AND AVOCATIONS

Trudi Fletcher

“Art is my life. I’ve been involved in art all my life. It is who I am and what I am. I’ve always tried to be me,” Trudi says. “In my case, I have always known what I wanted to do, and I am still doing it. Over the course of my career I have done watercolors, oils, silk screens, and batiks. But I think of myself primarily as an artist of watercolors.”

True to form, Trudi celebrated approaching her centenary with an art exhibit at the Tubac Center of the Arts, a nonprofit organization in Tubac, Arizona, south of Tucson. It was clear that she was more interested in her lifelong passion of painting than she was in becoming a centenarian, which she dismisses as if to say, ”What’s age got to do with it?”

“I feel 65,” she says. “People have always accepted me as a younger person; why should I tell them my age when I don’t feel it? I’ve always had friends who were younger, sometimes much younger, than I. But now, others think it’s a reason to celebrate living 100 years—so I’ll be a young 100!

“In fact, my 100th celebration was the first birthday party I’ve ever had. I was born on Christmas Day, so that is what was always celebrated. But this year my family came from out of state and we went to a nice restaurant for a real birthday party—not a Christmas celebration.”

Trudi is a native of Glendale, California, and a graduate of the California College of the Arts and Crafts. She was a high school art teacher during the 1930s, working her way up to department head. “Unlike many of my peers, I was not forced to retire when I married, but I chose to do so when my daughter was on the way in 1941. We moved to New York in 1942 because my husband had a good job offer—he was in finance. Eventually we settled in Ridgewood, New Jersey.

“Robert died in 1958 while my daughter was in college and my son in high school; I remarried four years later. We stayed in New Jersey for a couple of years and then moved to Tucson, Arizona. I enjoyed our frequent trips to Nogales, Arizona, and Mexico. Each time we went, we would drive past the tiny town—an artist’s colony, actually—of Tubac, population 200. In 1967 we moved there and I opened an art gallery with my sister, the Dos Hermanas Gallery (the two-sister gallery). I continued to run the gallery until I was 85. While I painted for the joy of it, I liked selling my works, too, and those of others, of course. My gallery was an extension of my interests.”

Trudi has found a way to blend her other interest into her art. “I have traveled extensively, studying with great teachers such as Dan Kingman and Millard Sheets, and I studied with The Art Workshop from 1962–2000. I kept on learning. I have taken two around-the-world trips when doing so was a big deal and still unusual. I’ve also returned to a lot of interesting places several times and have written 50 journals of my trips. It was especially wonderful traveling in the 1960s and 70s when everyone loved Americans, and before everything became westernized. You could go to Bali (I’ve been twice) and the locals were wearing their native costumes; that’s where I learned about Batik; and to Thailand with all its rich raw silk and beautiful colors; and before people in India were wearing jeans. They all look like they’re from New York now. I’ve been to China four times. I loved learning different ways of living and eating and dressing. I loved the native qualities of other cultures. I’ve been to Africa three times, Nepal twice, India three times.

“Bangkok was a beautiful place; I still have my spirit house in the living room. I’ve been to the Middle East—to Saudi Arabia and Dubai and Kuwait with my daughter. That was a university trip. I was in Burma when I was 85. That was my last big trip.

“More than anything, my art has been influenced by my travels, by the different cultures, textures, colors of foreign lands. There is always something new to learn. I always felt expanded as a person with each trip. I feel I was directed by my subconscious; everything I have done has been for a reason. This was my way of expressing myself and learning about the world. It is all reflected in my paintings.”

Trudi has no intention of putting away her paints and brushes. “I’m working in watercolors again,” she says. “My creative spirit remains strong. I’m still evolving. I developed a new style a couple of years ago. I tired of painting landscapes and still life—I began painting people, animals, and birds in a more abstract style—it’s been fun. I call my new works The 98s, after the age at which I began painting them.” It was these Trudi exhibited at her centennial show at the Tubac gallery. The colorful, cheerful works of art are very much a reflection of the bright, attractive artist herself.

Eleanor Harris

Although vision impaired, Eleanor Harris, 100, was determined to write her stories, as she calls her memoirs, for her sons and family. She began recording what turned out to be 14 tapes with the recorder one of her sons provided. The finished product was a bound book comprising 118 pages including photos of her life over the years.

“I was born in the small town of McCook, Nebraska, on April 4, 1912, at home, as most babies were then. I took up the violin at age 11 and music became my fascination, with music education my major when I attended McCook College. At that time it was only a two-year school. I then went to New York City for two years with a friend who was studying piano. She was 19 and I was 18. We went to the Institute of Musical Art, which was the undergraduate part of the Juilliard School of Music. Then I went back to the University of Nebraska to get my BA. I played in the symphony at the university. I then got a job as a music supervisor in Bayard, Nebraska. My contract stated that if I got married, I was fired. It was the Depression, so we would go along with just about anything.

Trudi Fletcher

“Anyway, I saved every cent I could and after two years had enough to move back to New York, where I wanted my life to be. I loved New York, the excitement, the pace, the places to go—the theatre, museums, and concerts—all of it! I went to Columbia and earned a master’s degree in music education. I had a grand life planned. I had two cousins who were there also, and we all graduated on the same day. Meanwhile, I had met a young man named John T. Harris, who had recently moved to New York from Alabama. He was really handsome. You can fill in the rest.

“After I graduated, we were married. When John T., Jr. was on the way, my husband said he didn’t want to raise a child in New York City, so we moved to Florida and then to Atlanta, where we had a lot of fun as a young married couple with a baby. We traveled a lot for John T.’s job, and the baby slept in a dresser drawer. We were all very happy. Intermittently, we would make trips back to John T.’s family home in Alabama.

“We moved back to my family home in McCook in 1945, where John T. managed our family department store and cattle ranch and feedlot. By now we had four sons. I had my sixth and last son in 1955 when I was 43, which was old for that time, but everything went well.