THE SPECIAL CHALLENGES OF SOVEREIGN FUNDS

Perhaps the most dramatic setting where governments have struggled with the challenges of being venture capitalists has been sovereign wealth funds. These funds, owned by a state that invests in various financial assets, represent in some sense the ultimate challenge in governmental support of entrepreneurship. In addition to the obstacles that all public efforts to boost entrepreneurship face, the size, demands for visibility, and complex mission of sovereign wealth funds are daunting.

This chapter will review the many issues these new investors encounter. After an overview of these complex institutions, we’ll discuss both the similarities to other public venture programs and the additional challenges sovereign funds face.

We will then consider how they can operate effectively. There appears to be no good answer to one critical question, how to cope with demands for transparency. Interests in many Western nations demand that sovereign funds provide detailed accountings of their activities. This request for openness can be readily understood, but such disclosures are likely to make it harder for sovereign funds to achieve their goals.

The available evidence offers more clear-cut advice when it comes to the challenges associated with the large size of sovereign funds. A number of approaches cultivated by effective institutional investors worldwide—from investing in the best people to pioneering new asset classes to compartmentalizing investment activities—seem readily applicable to these investors.

AN OVERVIEW OF SOVEREIGN WEALTH FUNDS

Depending on how one counts, there are between forty and seventy different sovereign funds, run by political entities as disparate as New Mexico and Kazakhstan. (Tables 8.1 and 8.2 illustrate the largest sovereign wealth funds and estimates of their holdings and growth.)1 Market estimates of their size are difficult to determine because they often lack transparency: disclosure regulations and practices differ widely from country to country. But in mid-2008, J.P. Morgan estimated that total fund assets were nearly $3.5 trillion.2 To place this figure in a broad investment context: the amount these funds currently manage exceeds the $1.4 trillion managed by hedge funds, but it is only 1.2 percent of global financial assets, which are about $190 trillion.

The wealth of sovereign funds has differing origins. In many of the most visible cases, such as Abu Dhabi, petroleum has been the source of abundant wealth. Other commodities, from diamonds to phosphates, have been the foundation of other funds. Still others have been primarily funded from the proceeds from privatizations, that is, the sale of state-owned properties or businesses. Many other funds, such as those of China and Singapore, have their origin in trade surpluses.

Table 8-1

Sovereign Funds with Over $100 Billion in Assets in Mid-2008

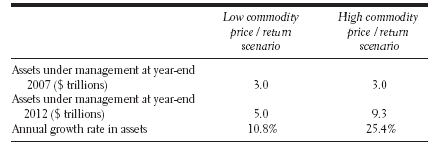

Table 8-2

Projected Sovereign Wealth Fund Growth

| Low commodity price / return scenario | High commodity price / return scenario | |

| Assets under management at year-end 2007 ($ trillions) | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Assets under management at year-end 2012 ($ trillions) | 5.0 | 9.3 |

| Annual growth rate in assets | 10.8% | 25.4% |

Most of their growth has occurred recently. In 1990, for example, fund assets were estimated at only $500 billion. Over the past three years, they have achieved a 24 percent annual growth rate and could grow to $12 trillion of assets—a growth rate of $1 trillion a year—over the next eight years.3 Much of this growth has been driven, not surprisingly, by the rising price of petroleum, and has been concentrated in producer nations such as Norway, the United Arab Emirates, and Kuwait. But other important players include nations such as China that pile up foreign currency because they run persistent, large trade surpluses. These countries less and less often put these reserves “under a mattress”—that is, holding safe but low-return Treasury bonds—and are instead seeking broader portfolios.

Sovereign funds frequently have multiple goals, which different organizations emphasize to varying extents. The most powerful motivation can be seen in the experience of Kiribati, a collection of islands in the Pacific Ocean formerly known as the Gilbert Islands, with a population of under 100,000 residents.4 For many decades, the dominant export from the country was guano, bird droppings used for fertilizer. The island’s leaders set up the Kiribati Revenue Equalization Reserve Fund in 1956, and imposed a tax on production by foreign firms. The last guano was extracted in 1979, but the fund remains a key economic contributor. At $600 million, it is ten times the size of the nation’s gross domestic product, and the interest generated by the fund represents 30 percent of the nation’s revenue.

There are three distinct roles sovereign wealth funds can play:

• They can serve as a source of capital for future generations, who will no longer be able to rely on commodities for a steady stream of revenue. Such a use is similar to that of a university that receives a major bequest: typically, these funds are not spent immediately, but instead added to its endowment so it can benefit many cohorts of students.

• They can play the role of smoothing revenues. Countries that depend on commodities for the bulk of their exports can be whipsawed by shifts in prices, as, for instance, many oil exporters were in the mid-1980s and late 1990s.

• Finally, these funds can serve as holding companies, in which the government places its strategic investments. Public leaders may see fit to invest in domestic or foreign firms for strategic purposes, and the sovereign funds provide a way to hold and manage these stakes.

THE GRIM LEGACY

In attempting to save money for the future, nations are departing from a long legacy of failure in managing the wealth created by natural resources. Consider, for instance, the experience of Norway in the 1970s and 1980s.5 In the oil surge of those years, the government received a tremendous windfall of funds from its numerous rigs in the North Sea. While efforts were made to enact legislation that set aside money for the future, no savings were made. Instead, the money was largely spent immediately.

Some of the spending benefited physical and social infrastructure: Norway rebuilt its excellent system of roads and bridges and provided free health care and higher education to all residents. But other expenditures were less beneficial. Minimum wages were set extremely high, several times the level in the United States. While well intentioned, this step rendered a number of economic sectors uncompetitive. Much of the funding for industry was earmarked for dying sectors, such as shipbuilding. This support allowed facilities to remain open for a few years more, but could not reverse the industries’ inexorable decline. Much of the funding for new ventures went to friends or relatives of parliamentarians or of the bureaucrats responsible for allocating the funds.

Moreover, the policy of aggressively spending the government’s petroleum revenues introduced chaos into public and private finances when the oil price plunged in the mid-1980s. The government’s oil revenue dropped from about $11.2 billion in 1985—or about 20 percent of Norway’s gross domestic product—to $2.4 billion in 1988. The resulting retrenchment of public spending and tightening of credit led numerous banks to fail. The resulting downturn also led to an unprecedented wave of bankruptcies by private citizens.

Nor was Norway the first nation to struggle with the influx of wealth, or what the Economist has termed the “Dutch Disease” (named after the economic malaise that gripped the Netherlands when it experienced an influx of natural gas royalties during the 1960s). Turning much further back in time, the historian David Landes documents the corrosive effects that the tremendous wealth generated by Spain’s overseas conquests had on the nation’s economy. Consider a communication from the Moroccan ambassador to Spain in 1690:

The Spanish nation today possesses the greatest wealth and the largest income of all the Christians. But the love of luxury and the comforts of civilization have overcome them, and you will rarely find one of this nation who engages in trade or travels abroad for commerce as do the other Christian nations.… Most of those who practice [handi]crafts in Spain are Frenchmen [who] flock to Spain to look for work … [and] in a short time make great fortunes.6

The “curse of natural resources” is a well-established pattern. In his exercise to determine the impact of different variables on economic growth, titled “I Just Ran Two Million Regressions,” Xavier Sala-i-Martin seeks to explain growth rates across a large number of nations between 1960 and 1995.7 He finds that roughly ten sets of variables have consistent explanatory power, including geography (being farther away from the equator is better for growth), the economic system (capitalist societies grow more quickly), and religion (Buddhist, Confucian, and Muslim nations experienced faster growth than Catholic and Protestant ones). Among these consistent variables is the abundance of natural resources—measured using the share of exports from agricultural and extractive industries—which has a negative impact on growth. This finding has been echoed in many papers.

But where does this curse come from?8 One suggestion is that it may reflect a crowding-out effect. Nations that devote more of their resources—for instance, public spending and management talent—to exploiting oil and other commodities weaken their manufacturing and services sectors. For instance, manufacturers may struggle to find talented people at reasonable wages, and may find it hard to export because the nation’s currency is strong relative to others. And it may be that a healthy manufacturing and service sector is critical to long-run growth.

Another possibility is that an abundance of natural resources exacerbates the capture problems we discussed in chapter 4. The profits from natural resource projects are typically concentrated in a few, easily identified hands. The temptation for government officials to guide benefits to their friends (and sometimes themselves), rather than choose policies that would be best for the nation’s future growth, may become too large. Moreover, the easy profits from such shakedowns may lure the most talented people into unproductive—though very lucrative—jobs in the public sector, when society as a whole would be much better off if they pursued entrepreneurial efforts. These dynamics might lead natural-resource-dependent countries to have poorer governments, less innovation, and ultimately lower growth. Even if public corruption is not widespread, active public management of the natural resources can lead to an economy where the public and private sectors are intertwined. While there are exceptions, often these intermeshed economies are less flexible than their alternatives.

Sovereign funds can address these downsides of a wealth of natural resources—and potentially undo the negative relationship between growth and natural resources—in two ways. First, by not spending the gains from natural resources immediately, but rather preserving them for future generations, the distorting impact of the windfall is reduced. Had the Norwegian government kept public spending in check during the 1970s and 1980s, it is unlikely that the disruptions in subsequent years would have been as severe. Second, earmarking a percentage of natural resources revenues into an investment fund may reduce capture problems. Such a step reduces the likelihood that government officials will spend these revenues in an unwise or corrupt manner—assuming, that is, the sovereign fund is run in a professional manner.

THE FUTURE OF SOVEREIGN FUNDS

In some ways, then, these are the best of times for sovereign funds: they have experienced tremendous growth and are likely to continue to do so. In a number of cases, the size and sophistication of the investment teams employed have grown substantially. A number of these groups have abandoned overly conservative strategies and adopted allocations more consistent with “best practices”: for instance, Norway’s Government Pension Fund increased its allocation to emerging markets and real estate in May 2008.

But at the same time, sovereign wealth funds face a raft of challenges. Many of them are common to other government venture promotion schemes more generally: for instance, the temptation to invest too locally without considering broader options, a failure to assess performance, and pressures to invest in the “pet projects” of political leaders and their associates. But they also face two additional pressures, which make leading such an organization particularly challenging.

Challenge 1: Visibility

The first of these is the increased political scrutiny of these organizations in many nations. Although sovereign wealth funds have existed for more than five decades, they have attracted considerable attention recently because of their accelerating growth and because of highly public transactions that drew them into the global spotlight, such as the $7.5 billion investment in Citigroup in November 2007 by the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority. The controversies surrounding investments by sovereign funds are not new—witness the 1987 row over the Kuwait Investment Office’s purchase of a 20 percent stake in British Petroleum—yet the intensity of scrutiny in recent years has been unprecedented. Nor is it likely to subside, at least if the growth of these funds continues unabated.

What is behind this fear of sovereign funds? In part, it can be attributed to intense anxiety in many established economies about globalization and the changing global balance of power. It is far easier to blame an institution than vaguely understood economic forces.

Indeed, many of the fears about sovereign funds appear misplaced. Press accounts and political rhetoric have depicted these funds as focusing their investments on politically sensitive sectors in the most developed nations, and suggested that they pose a strategic risk to these nations. For instance, former U.S. Treasury secretary and Harvard president Larry Summers has stated,

The logic of the capitalist system depends on shareholders causing companies to act so as to maximize the value of their shares. It is far from obvious that this will over time be the only motivation of governments as shareholders. They may want to see their national companies compete effectively, or to extract technology or to achieve influence.9

Whatever the reasonableness of Summers’s critique on a theoretical level, it does not seem to describe real-world behaviors. A recent Monitor Group study showed that the bulk of investments focused on domestic and emerging markets, rather than the West. If anything, these investors have tended to shy away from high-profile sectors in developed nations: the investments in 2007 and 2008 in ailing financial services firms (particularly investment banks) were the exception rather than the rule.10 (Based on the miserable subsequent performance of many of these financial firms, many funds probably wish they had not taken this detour.) And it is hard to deny that these investments during the credit crunch were beneficial to the United States and other developed countries, as they introduced much-needed liquidity into the financial system at a critical time.

But at the same time, the sovereign funds have not helped themselves with the intense secrecy that surrounds some of their activities. Greater visibility—publicizing the size of the pools, investment strategies, and particular investments—could help dispel at least part of the worries over sovereign funds.

Valuable lessons may be drawn from the experiences of the private equity industry. Buyout funds have operated happily in the shadows for many decades. In recent years, however, they have been singled out for scrutiny in many Western nations. To cite just a few examples:

• Franz Müntefering, the head of the Social Democratic Party (and subsequently the vice-chancellor of Germany), attacked private equity groups and hedge funds, describing them as “swarms of locusts that fall on companies, stripping them bare before moving on.”11 A leaked party document listed a number of such “locusts,” including the Carlyle Group and Goldman Sachs.

• Korean authorities, angered at the profits that Carlyle, Newbridge Capital, and Lone Star have made from their investments there, have launched enforcement actions, including raids on the offices of private equity groups.

• In both Japan and China, the government has proposed new rules affecting the taxation and regulation of activities of foreign investment funds. At least in part, these actions have been triggered by anger over the success of groups such as Ripplewood.

• A number of European nations have changed the tax treatment of private equity, such as Denmark’s imposition of limitations on the deductibility of interest payments.

Many of the charges leveled against the private equity industry—such as claims that buyouts are typically associated with massive job losses or short-term horizons—do not stand up to scrutiny. For instance, while private equity investments in the United States do seem to be associated with slower job growth (or faster job losses) than at comparable firms, this effect is almost entirely offset by the greater level of job creation at new facilities by bought-out firms. Looking at one particular form of long-run investment, the pursuit of innovation, also paints a very different picture than that depicted by the critics. Rather than cutting back on innovation, the aggregate level stays roughly the same after a buyout. But the awards applied for by private equity-backed firms prove to be far more economically impactful than the ones sought earlier. In short, the firms seem to rearrange their research portfolios, substituting high-impact efforts for the more marginal activities pursued before the buyout.12 While there is certainly behavior by buyout firms to criticize—in particular, the periodic periods of overheating that characterize the industry, when too cheap debt leads to a flurry of excessive leverage and overpriced transactions—many of the claims by the industry’s critics seem overstated.

Despite the dubious foundation of many critiques, they have attracted attention from the media, politicians, and voters alike. As I discussed above, these charges have affected public policymaking in important ways. Leaders’ concerns about economic disruption and the secrecy of the industry seem to have exacerbated this reaction.

It is important for sovereign funds, like the private equity industry, to address these concerns proactively. Ensuring transparency about the story behind the funds, the way they operate, and the consequences of investments is important. Encouraging objective research by outsiders that can better document the funds’ roles and performance can also help alleviate doubts.

At the same time, two cautions should be noted. First, too much disclosure can have real costs. The costs can be seen most dramatically on American college campuses. In recent years, student activists at a number of elite universities have demanded greater disclosure of their endowment’s holdings. Yet, the endowment managers have vigorously resisted these cries.

Does the endowment chieftains’ reluctance to provide detailed information about their holdings mean they have something to hide? Why else would they be unwilling to reveal what they own? In truth, there are reasons to maintain some secrecy.

A crucial issue is that the strategies of the elite investors—whether endowments, pensions, or sovereign wealth funds—are being scrutinized and imitated as never before. In the past, there was often a substantial lag between the time endowments first began investing in an asset class and the time other institutions followed. For instance, many of the Ivy League schools began investing in venture capital in the early 1970s, but most corporate and public pensions did not follow until the 1980s and 1990s, respectively. But today, the lags are much shorter. Within a couple of years of Harvard’s initiating a program to invest in forestland, for instance, many other institutions had adopted similar initiatives. The same dynamics also play themselves out at the individual fund level: an investment by an elite endowment into a fund can trigger a rush of capital seeking to gain access to the same fund. Such an influx can make it much harder for the investor to continue its successful strategy. Thus, the greater disclosure demanded by campus protestors would likely intensify the problem of imitative investment, leading to lower returns and fewer resources for future generations of students. Detailed disclosures by sovereign funds could lead to the same problems.

Furthermore, even an aggressive policy of encouraging transparency will not solve all of the challenges that sovereign wealth funds face. Investment decisions that would seem unremarkable when made by an individual or institutional investor can become political hot potatoes when undertaken by a sovereign fund. Consider, for instance, the experience of Norway’s Government Pension Fund.13 When the fund trimmed its portfolio of firms using child labor, it sold $400 million of Wal-Mart stock. This decision triggered a diplomatic row with the American ambassador, who accused Norway of passing “essentially a national judgment on the ethics of the [company].” (The fund pointed out that when it had shared with Wal-Mart its draft report presenting evidence about the company’s labor practices, Wal-Mart ignored it.) Similarly, when the Norway’s fund, along with many hedge funds, presciently sold short the shares of Icelandic banks in 2006, it triggered a major diplomatic row with that nation.

Challenge 2: Maintaining Returns

The second challenge sovereign wealth funds must address is that of ensuring attractive investment returns. Strategies that work for a modest-sized institution—for instance, a university endowment with a few billion dollars under management—may be difficult to scale up into a larger organization. For instance, it may be possible for a billion-dollar endowment to generate attractive returns from investments of $10 million apiece in equities in second-tier exchanges and in developing markets. If a sovereign fund with 100 times the capital were to pursue a similar strategy, it would probably (a) be unable to identify enough attractive investments to have a return that significantly boosts that of the overall fund; or (b) find that purchases of larger blocks of stock so affected the market price that the strategy was far less profitable. Indeed, many endowments have struggled to maintain their success as they have become larger. Thus, for the larger sovereign funds, generating attractive returns is by no means simple.

This problem is particularly acute as sovereign funds put more emphasis on alternative investments, such as private equity and real estate. These sectors have been critical to the extraordinary success university endowments have enjoyed. For instance, when one examines the investment performance of Ivy League schools between 2002 and 2005, the only word that can characterize it is “spectacular”: funds earned almost 12 percent annually in a period when most market indexes did far worse. This result is inexorably linked to the funds’ use of alternative investments: when one compares the funds’ earnings during these years to benchmarks, fully 94 percent of the excess performance can be attributed to hedge funds, private equity, real estate, and venture capital.14

But academic research suggests that these sectors are particularly vulnerable to influxes of new capital. Because there are often limited opportunities in a given sector, additional capital tends to be associated with unfortunate events, as we saw during the “venture bubble” of the late 1990s and the “buyout bubble” of 2005–7. These periods typically see the entry of many new funds, which tend to perform much more poorly than established groups. Groups already in the market raise larger funds: rapid growth, while it leads to more fees for the fund managers, is also associated with a decline in returns. Even groups that remain disciplined and resist the temptation to grow may find their returns suffering in a more competitive market. In many instances, the phenomenon of “money chasing deals” leads all firms to pay higher prices to acquire firms than in normal times. In venture capital, for instance, a doubling of flows of funds into the sector is associated with funds paying between 7 and 21 percent more for an otherwise identical transaction.15 All these factors—the entry of inexperienced investors, too rapid growth among established players, and the purchase of securities at higher prices—lead to lower returns. Because some sovereign funds are so large, there is a good probability that their moves into alternatives will coincide with periods of overinvestment.

Moreover, the various goals that motivate sovereign funds may be in conflict. Given the relative youth of most sovereign funds, this conflict is difficult to illustrate, but we can look at the experiences of other long-term investors. A stark example is the University of Rochester, which in the early 1970s had the third largest endowment in the country (after Harvard and the University of Texas).16 The administrators responsible for it made the fateful choice to heavily allocate investments to local companies such as Kodak and Xerox, which suffered substantial reverses during the 1970s and 1980s. As a result of this miscue and others, Rochester suffered poor returns in these decades. By 1995, its endowment was only the twenty-fifth largest in the nation. As a result of financial troubles largely brought about by its underperforming endowment, it was forced to dramatically downsize its faculty and programs in the mid-1990s. In this case, the goal of supporting local businesses ran counter to the goal of buffering the university against financial shortfalls.

Thus, sovereign funds have to figure out how to grow rapidly while generating attractive investment returns. The task is not an easy one. But three approaches across the world of institutional investors stand out as models, which are well worth serious consideration.

Be independent minded. First, it does not make sense to emulate exactly the allocations and approaches that have been successful for others in the past. Markets that generated extraordinary returns in earlier years are unlikely to continue to do so. For instance, endowments such as Harvard’s and Yale’s have benefited tremendously from Silicon Valley–based venture capital funds over the past three-and-a-half decades.

But for a sovereign wealth fund beginning an alternative investment program today, this route is unlikely to be lucrative. It is virtually impossible for a new investor to get access to the top-tier U.S.-based venture groups, who have generated most of the outsized returns in the sector. Moreover, because the sector has matured, returns will likely be far more modest than in the 1980s and 1990s.

Instead, relatively undiscovered investment classes seem like a far more rewarding strategy. Whether African stocks or infrastructure projects in central Asia, these new classes of investments are similar to the pioneering Silicon Valley venture funds in the early 1970s. To be sure, there are enormous risks, and even the range of possible outcomes is not fully understood. But if the apparent opportunities in these sectors materialize, and the sovereign funds can find the right teams to work with, these new areas are likely to yield attractive returns to the funds for many years to come.

Invest in the best people. Second, building a successful program is a major investment. Without a long-run investment strategy and a process of careful evaluation and strategic fine-tuning, returns are likely to be poor. Both of these factors depend critically on the recruitment and retention of top-notch managers and advisors. Far too many financial institutions have tried to build programs on the cheap, not understanding the benefits that a stable, experienced core of investment professionals can bring. Sovereign funds that have not been willing or able to bring in a successful investment team would have been far better off had they simply put their capital into index funds that track the market.

Consider, for instance, a number of state pension funds in the United States. Not only are salary levels far below comparable rewards in the private sector, but there are too few efforts to make the work rewarding. Rather than emphasize the broad mission of the investment office, administrators often limit the discretion of investment professionals. Recommendations of the staff are all too often overturned by a second-guessing investment committee. It is thus not surprising that many of these institutions are characterized by a revolving door, with employees lingering just long enough to become attractive to employers in the private sector.

Adequately compensating personnel is, of course, easier said than done. A tremendous distaste surrounds the payment of “excessive” compensation to those in the public trust. But if sovereign wealth funds are going to ask their staffs to play roles akin to those of private equity investors—and expect to recruit and retain skilled professionals—adjusting compensation schedules to more clearly mirror those in the private sector is essential.

This mission can be particularly difficult in democracies, where the media may misrepresent compensation arrangements. Consider, for instance, In-Q-Tel, which, while not a sovereign fund, dramatically illustrates this problem.

In-Q-Tel was established in 1999 to give the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency greater access to cutting-edge technologies.17 At the time of its establishment, the U.S. intelligence community realized it was being overwhelmed: not only had the volume of Internet and telephone communication exploded to the point where it was impossible to monitor, but the nation had to worry about many more enemies than in the Cold War days. The agency’s scientific leaders also realized that the most sophisticated technologies were being developed not within government laboratories, but rather in Silicon Valley startups. Brilliant engineers that in earlier days might have been lured to work in advanced government facilities were instead streaming to young firms in the hopes of hitting it rich.

In-Q-Tel was designed to address this problem by allowing the government to access some of the key innovations in these firms. Using a variety of venture-like tools, the organization invested modest stakes in emerging companies, often in conjunction with independent venture firms. It also served as a bridge, introducing firms in its portfolio to the intelligence community and highlighting the government as an important new customer for their products. For many of the start-ups, which had targeted corporate customers, the challenges of breaking into government procurement were daunting. For instance, Las Vegas–based Systems Research and Development employed “Non-Obvious Relationship Analysis” to allow casinos to identify card counters and cheaters. Jeff Jonas, the firm’s chief executive officer, considered selling the technology to the government for national security applications, but noted, “It was very hard to be a West Coast company that’s never done anything in Washington, with no visibility or awareness into sensitive federal agencies. You can’t just show up from Vegas and say ‘So you want to buy a watch?’”18

The CIA realized it needed a special kind of team to run In-Q-Tel: individuals who were at once conversant with the world of high-technology start-ups and with a ponderous, security-conscious government bureaucracy. To maximize the chance of getting the right people, the CIA set up In-Q-Tel as an independent, not-for-profit entity, which shielded it from civil service rules that might discourage many recruits. While the agency believed the primary lure for working at In-Q-Tel would be the opportunity to fund cutting-edge technologies and to help the nation, there was also a need for a diverse array of people at the fund. For every gray-haired executive who had already struck it rich in high technology, there should be several younger associates. In order to attract these staff members—and to avoid a revolving door through which people left as soon as they had the requisite experience—the CIA designed a compensation scheme quite different from that in typical government jobs. The package included a flat salary, a bonus based on how well In-Q-Tel met government needs, and an employee investment program, which took a prespecified portion of each employee’s salary and invested alongside In-Q-Tel in the young firms in its portfolio. With this arrangement, In-Q-Tel was able to attract a strong team, including, as CEO, Gilman Louie, a twenty-year veteran of Silicon Valley and head of a number of successful game companies.

After a few years of operations, however, the New York Post—a newspaper better known for covering the barroom and bedroom escapades of actresses, politicians, and ballplayers—decided to turn its attention to In-Q-Tel.19 Describing it as “an astonishing tale of taxpayer-financed intrigue on capitalism’s street of dreams,” journalists homed in on the compensation scheme: one article charged that In-Q-Tel employees were “speculat[ing] with taxpayer money for their own personal benefit.” Needless to say, there was no discussion of the challenges of recruiting investment staff conversant with Silicon Valley, or the likelihood that many In-Q-Tel professionals could make far more in the private sector. This arrangement, the Post intoned, was “almost identical to the so-called ‘Raptor’ partnerships through which top officials at Enron Corp were able to cash in personally on investment activities of the very company that employed them.” (Never mind that such arrangements have also been used by many of the best corporate venture partnerships …)

While In-Q-Tel continues, Gilman Louie himself in early 2006 began his own venture capital fund with seasoned investor Stewart Alsopp. His colleague Mark Frantz, a managing general partner at In-Q-Tel, left about the same time to become general partner with Reston, Virginia’s Redshift Ventures, formerly known as SpaceVest. Whether it was compensation levels—which while attractive by government standards, were far below those of independent venture capitalists—the distractions associated with frequent congressional investigations, or the media scrutiny, In-Q-Tel has struggled to hold onto its investment staff, despite a creative attempt to create attractive incentives.

These problems are not unique to democracies, though. A number of sovereign funds in other nations have suffered from a brain drain as the most experienced operatives have left to begin their own firms or join independent groups. In these cases, the crucial limitation has been not the fear of a crusading press, but rather reluctance by government leaders to offer pay that might be perceived as unfair or disruptive.

In short, the need to view the development of a sovereign wealth fund as an investment is critical. Just as with a public building project, these offices require careful planning and the recruitment and retention of top-tier staff. In this area, enduring success comes not to the lucky, but rather to those who take a thoughtful approach!

Go small. A final point is to emulate smaller institutions. In extreme cases, the size of sovereign funds can be so great that a kind of paralysis sets in. To have the probability of contributing meaningfully to returns, each investment needs to be so large that smaller investments don’t get made, even if collectively they would have a substantial impact. And it may be that the very large investments the fund does get offered are not the best ones.

One way around this constriction is to build an organizational structure in which a number of subsidiaries are managed separately. In this way, managers can make smaller investments, secure in the knowledge that if successful, they will affect their own performance. Such separate funds can also serve as “laboratories”: successful approaches can be emulated by the other funds, while mistakes can be less costly since they affect only one subsidiary. (This approach resembles the “skunk works” and corporate venturing programs that major technology firms have employed in their research laboratories.)

Several illustrations of such an approach can be pointed to. For instance, since 1960, Sweden has operated a number of independent pension funds.20 Now numbering seven in total, the funds were envisioned as operating independently, on mutually competitive terms. Each fund, in theory, is allowed to formulate its own investment approaches, corporate governance policies, and risk management strategies. While the Swedish regulators have not allowed as much competition as might be desired—the funds have had to keep a chunk of their assets in bonds, and been strictly limited in the amount of alternative investments they can hold—the idea of fostering competition between funds is a laudable one. In a somewhat similar spirit, the Government of Singapore Investment Corporation has established separate subsidiaries for asset management (liquid investments), real estate, and special investments, each with its own chairman, board, and president.21

FINAL THOUGHTS

In many respects, the challenges associated with managing sovereign wealth funds are similar to those facing other public venture initiatives. Because they often operate in the public spotlight, decisions must be made with a complex set of goals in mind and in the face of external pressures.

But in two key respects, the management of sovereign funds poses unique issues. First, the quantity of capital these groups invest is in many instances massive, which limits their flexibility in pursuing new opportunities. Second, the intense interest in—and in some cases, fear of—sovereign wealth funds in many Western nations increases the difficulty of fulfilling their already challenging missions.

In this chapter, we have explored the complex world of sovereign wealth funds. We have acknowledged that demands for visibility pose a problem for which we have no good solution. Such disclosures—while perhaps necessary from a political perspective—are likely to make the funds’ goals harder to achieve. But the process of managing increasingly large amounts of capital can be addressed. The best practices of endowments and other seasoned institutions illustrate how to manage substantial assets while maintaining a clear focus.