CHAPTER 13

Silicon Valley, Wall Street, and the Factory Floor

Our society faces an unprecedented degree of division. The first quarter of the twenty‐first century has seen industries turned upside down, the creation of new markets, new social and class structures, a dramatic shift in the day‐to‐day human experience, and increased economic imbalance.

It is surprising to remember or believe that in 1997, the domain “google.com” was registered, Netflix was founded, smartphones did not exist, and the percentage of personal computer ownership in the United States was only 35%.1

The Divide Within

If organizational functions were categorized into the most simplified buckets, they would be technology, business, and industry. Many individuals span more than one of these buckets, especially as they move into leadership positions, but it's important to draw this distinction because it provides a taxonomy for examining the divide within organizations that has taken place in the first quarter of the twenty‐first century.

One of the earliest social shifts has been the transition of technology professionals from the back office to the boardroom and into leadership positions throughout companies. The mandate for every business to become a digital business lest it go the way of Blockbuster has led to this shift in decision‐making power. This has been and remains a profound cultural shift. IT leaders have transitioned from supporting business functions, setting up intranets and maintaining computer hardware and software, to informing business decisions, advising which Internet hosting service should be purchased to create the organization's website and whether the organization's inventory can be converted to a database, to leading board‐level agenda items: organization‐wide digital transformation or new digital lines of services or products.

If we look back further than 1997, we observe a similar shift in the decision‐making power transitioning from industry leaders to business leaders in a repeated cycle on a micro level, and on a macro level in the twentieth century as business leadership rose to an elite profession due to the influence of the world wars and the Depression.

Artifacts of these dissenting factions can be found today, some of which are quite obvious. Shadow IT is a chief example, as it gives business and industry leaders control over their technology choices, spend, and implementations. Regrettably, it damages the broader system of the organization. Disagreements about building‐versus‐buying capability is another example of these misalignments. One firm I worked with was deep into the due diligence process of a proposed several‐hundred‐million‐dollar acquisition when the question was raised as to whether a “build” assessment had been run on the underlying technology. It had not been considered. The business leaders wanted the capability as soon as possible, and were willing to spend almost 100 times more (the analysis ended up revealing this cost differential) to buy the capability than to bring their internal technology organization into the discussion.

A further divide between these disciplines (business, technology, and industry) arose when some technologists realized they could speak the language of technology any time they wanted to skirt a business conversation or, worse, mislead business and industry leaders.

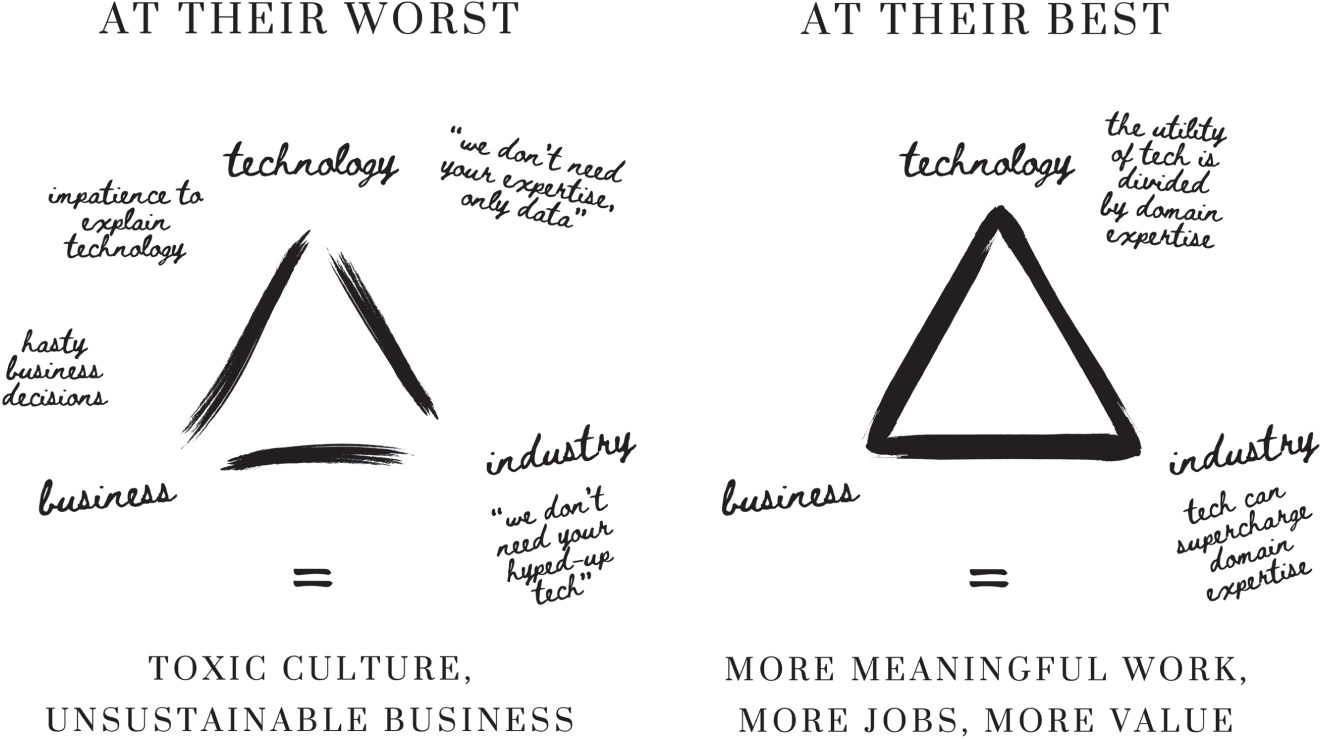

In Figure 13.1, you can see the juxtapositions of these factions at their best and at their worst. At their best, technologists understand that their technological capabilities are only as valuable as the business models and domain expertise with which they are paired.

The economic potential when leaders can balance this equation across organizations is exponential.

An imbalance in the equation is found when organizations are operating at their worst: disrespecting one another's expertise, making decisions in silos, and holding back the organization's ability to create value and make meaningful impact. This is unsustainable from both a profit and a culture perspective, tipping the organization into a nosedive.

Figure 13.1 The Division of Expertise

The Divide Across

The View from One Side of the Field

The technology consulting and technology industries are home to an immense amount of technological capability. These organizations face a different set of challenges than those outlined in the previous section as there is a natural alignment and orientation toward technology across technology, business, and industry leaders because the industry is also technology. The greatest challenge arises when these organizations approach other industries in attempts to partner or to sell software and/or services.

When a consultant or software professional approaches an organization outside their industry, the first two decisions they must make are at which altitude should they start the conversation, and whether to approach the technology, business, or industry organization within their target client. Both come with trade‐offs and are influenced by factors such as the applicability of the technology, existing relationships, and balance of trade.

Consultants and software professionals are often instructed by the chief information officer (CIO) or someone in the CIO's organization, for example, to never hold a discussion with business or industry leaders in the organization without members of the information technology organization present. From a balance of trade perspective, if the information technology organization is spending tens of millions of dollars on a managed service or software licensing, it may not matter how applicable the technology could be to another organization or where there may be existing relationships.

Alternatively, if a new relationship is budding between a software advisor and an industry leader, the software advisor may be advised not to connect with or consult with the information technology organization.

Both of these behaviors are harmful to the overarching organization and can be difficult for software and advisory leaders to navigate.

The View from the Other Side of the Field

Most business and industry leaders have a handful of technological advisors they trust internally and externally. When the technology, business, or industry evolves past the capabilities of those advisors, however, or in the case of attrition, how do you find the right next advisors?

The rift between the technology, business, and industry factions becomes even more apparent and problematic in this scenario, where the technology organization is external to the business and therefore does not share the same fiscal incentive to ensure success.

This is compounded by the misdeeds of some technology advisors, motivated by short‐term gain or attempting to overcome a lack of expertise. Any technology advisor attempting to build relationships with new potential clients must first undergo pressure testing to demonstrate both credibility and trustworthiness, and rightfully so. Technology's ability to create value is equal to its ability to create harm. Thankfully, the majority of failed projects stop at having wasted resources, tossed aside once it becomes clear that the solution will not solve the problem for which it was being developed or implemented. Regrettably, these instances further deepen the wedge between technology, business, and industry leaders.

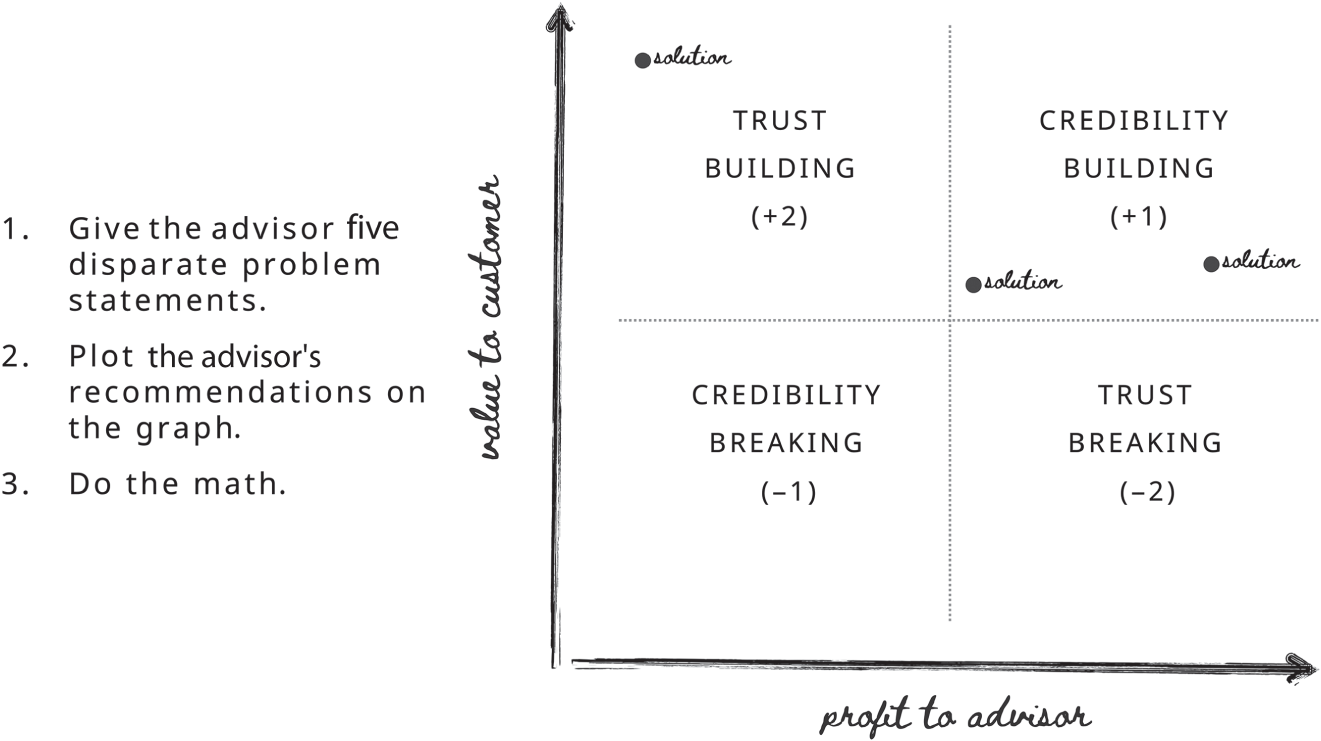

If you are a business or industry leader, you are likely inundated with messages from technology advisors asking for 10 minutes of your time to share a demonstration of their software, a discussion of their capabilities, or to discuss your needs. The painful truth for many in this position, beyond the lack of trust at the starting line, is the lack of time and resources to sufficiently vet each individual salesperson, technological capability, or solution. The test shown in Figure 13.2 can be leveraged to aid in navigating new relationships with technology advisors.

The Economic Incentive Test (Figure 13.2) can illuminate the trustworthiness of an advisor or salesperson before any meetings take place, and requires only three steps:

- Give the advisor five disparate problem statements.

- Plot the advisor's recommendations on the graph.

- Do the math.

Figure 13.2 The Economic Incentive Test

Creating five problem statements should be relatively simple for any business or industry leader. The key for this test to yield results is to make sure the statements are disparate or diversified enough that most technology solutions cannot and should not be able to solve them all. This provides an opportunity to see how the advisor or salesperson handles the problem statements for which their technology is not a fit. If, for example, they zero in on the single problem statement for which their technology is applicable, ignoring the rest, that is a different kind of approach than an advisor who acknowledges that they can only help you with one, but they have industry contacts or others within their company to whom they could introduce you to look into addressing the other four. The quality and applicability of those recommended additional contacts and their related products and/or services also speaks to the advisor's credibility. The difference highlighted in this example is approaching the relationship in a transactional capacity, where a salesperson is only listening for use cases for which there is a sales opportunity, as opposed to approaching the relationship in an advisory capacity, focused on adding value beyond individual sales opportunities. You will thank yourself down the road for making this distinction upfront.

A fictional example illustrates this test in action:

Wei is a leader at a large manufacturing company. She is approached by Anders, who works for a consulting firm. Anders reaches out to Wei, requesting time to make introductions and to learn more about what challenges Wei's organization may be facing. Wei replies that she appreciates Anders’ reaching out, that she does not have a lot of time to meet, but she would be interested in Anders’ perspective on five challenges her organization is looking at solving in the near future, the details of which she shares in an attachment. Anders replies after two business days and shares a document containing proposed solutions, with documented assumptions and questions that need validation, to three of the problem statements. In his note, he calls out that his practice does not focus on the other two problem areas, but that he has a colleague who he believes could be helpful in addressing them, if Wei does not mind his making an introduction and sharing details with them.

In the presentation, Anders shares details on how his practice would approach the three applicable problem statements, but that he believes they should start with the solution (pictured in the “Trust Building” square of Figure 13.3) where Wei's organization will realize the most value with the lowest initial cost. According to the grid shown in the figure, this is a trust‐building proposition. Anders could have skipped that problem statement or reordered it behind a problem statement that would have secured him a higher initial deal size. His choice is a signal of trustworthiness. Whether the solution is correct or the technology is sound must still be vetted, but at this stage, the recommended starting point and the fact that all three proposed solutions score positively in the test (with a total score of 4), Wei can trust that the advisor is choosing a trustworthy sales and partnership approach.

Figure 13.3 The Economic Incentive Test (Plotted)

If you begin using this test, you will see thresholds begin to emerge and, as you take risks on new technology and/or consulting partners, tracking their long‐term credibility and trustworthiness back to how they initially scored on this graph will inform whether you should consider raising or lowering your threshold.

If you are a technology sales director or managing partner at a consulting firm, you can use this test in interviewing and training new hires, as well as reviewing proposals of team members to measure and improve their projected credibility and trustworthiness over time.

This test is a starting point in taking extra steps to carefully examine our own credibility and the credibility of those approaching us with solutions to begin closing the divide across organizations.

The Divide Without

Our world is faced with social tensions between classes and geographies. These have been exacerbated by the economic imbalance created by the past several decades of technology growth. The underlying issues range from unequal access to opportunity to bias in the application of technology, the creation of an entire market focused on extending screen time, the shifting of classes in favor of those working in the technology industry, and outright unethical practices (to name a few).

Resolving these societal, systemic issues is a moral obligation on an individual level. Unfortunately, individual moral obligation has often been demonstrated to be insufficient to drive change through a system, much less a network of systems. Demonstrating positive influence on the business, however, can be and has been leveraged to generate organizational and societal momentum.

The digital divide, first revealed by the United States Department of Commerce in 1995, has a direct correlation to organizations now and in the future. The system in which an organization physically exists contains talent pools and long‐term talent pipelines. Addressing the digital divide in the local communities in which an organization operates benefits the long‐term continuity of the organization due to the development of local talent. It also has implications on attracting and retaining talent, and positively influencing the organizational culture with meaning and belonging.

Seattle is a great example of this. Known as the cloud capital of the world, the “system” of Seattle currently includes Amazon, Boeing, Microsoft, Nordstrom, SAP Concur, Expedia, multiple offices for Google, Meta, SalesForce, Tableau, and a host of other businesses.

A child growing up in Seattle today is highly likely to meet someone who works at one of these companies, go to school with children of employees of these companies, have access to a computer or tablet at a young age (provisioned by the school), have STEM options before, during, or after school, and have a clear understanding of what it would be like to have a job in the technology industry.

In contrast, a child growing up in a town with less organizational presence will need intervention to experience the benefits of the virtuous cycles that exist in cities like Seattle. Some of these interventions (the provisioning of devices and STEAM educational opportunities) can be funded by governmental education systems, but organizations that exist within the system have a symbiotic opportunity to lend their resources to contribute to the social good and to ensuring there is a steady flow of local talent development for the future.

Note

- 1 U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Computer Ownership Up Sharply in the 1990s,” Issues in Labor Statistics 99‐4 (1999).