12

Genre characterizations, both academic and not, conjure up a singular look and feel to the genre film. A Western has a moral main character and the antagonist has an immoral character. They settle their conflict violently against a backdrop of beautiful vast open spaces.

The gangster film has an urban setting that makes the gangster’s struggle modern. But the means of conflict resolution remain violent.

These characteristics are accurate but limiting. Genre has always been flexible, pliant to creative reinterpretation as well as the audience’s insatiable craving for novelty. Although we will use specific genres to illustrate genre flexibility, it might be useful to contextualize the range of flexibility, by looking at two particular storytellers who in their work not only capture the advantages of genre film, but also seek their own imprint on those films.

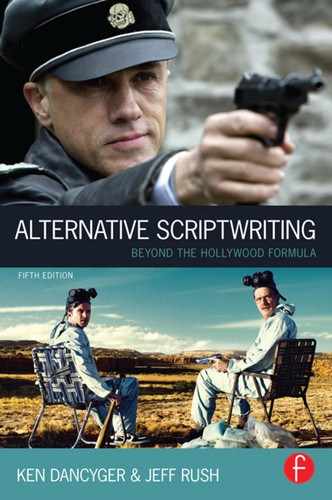

Quentin Tarantino, Genre Riffs

Quentin Tarantino has made a career by adapting a particular genre and playing with the form. Two striking examples make my point. Pulp Fiction (1994) is a gangster film, albeit an unusual one.

The gangster film tends to proceed in a straight line from the beginning of the gangster’s career to its bloody end. The gangster’s rise from obscurity to his precipitous fall is the plot of the gangster film. The characterization is equally particular. The gangster is a recent immigrant with strong roots in family. He wants the good life for his family and his career as a gangster is the means of access to the good life.

In Pulp Fiction, Tarantino abandons a linear structure and frames three episodes, short films rearranged to present out of a time chronology. He organizes the three episodes around a robbery that bookends the entire film. At the end, we realize the robbery takes place before the three short episodes occur. Neither the frame nor the three episodes bring logic and linearity to the overall screen story.

The first story introduces us to two hit men en route to their work, the killing of an outlier client and his team. The tone of the episode is garrulous, funny, and when the violence is unleashed, it’s shocking given the humorous exchange between the two hit men. Tonal variance from the classic gangster film masks the violence Pulp Fiction shares with Scarface and other classic gangster films.

Comedy and violence characterize the second and third episodes of Pulp Fiction. The third episode drifts away from the classic in its philosophical musings about remaining in the profession. Here the dialogue aims for something much deeper than its use in the first episode. Tarantino in both cases has used and overused dialogue to replace the action we expect in the gangster film.

In Inglorious Basterds (2009), Tarantino is using the war film as the basis for his riff. In the war film, a main character, usually a soldier, tries to survive. The plot may be a battle or an incident. Opinion about war and its influence on human behavior, articulates the voice of the writer and/or director on the issue of war. The tone tends to the realistic.

In Inglorious Basterds, the tone ranges from the realistic (Chapter 1) to the absurd (the killings of the Nazi hierarchy in the theater). What is at stake in war? Is it life itself? Is it adventure? Perhaps is it all about personal survival as opposed to belief? Perhaps. Tarantino is making a war film and at the same time deconstructing its motifs and satirizing them. As a result, there are no real heroes, villains are more interesting than heroes, and revenge trumps all other human values. This leaves us thinking about the war film just as Pulp Fiction left us thinking about the gangster film. It’s as if Tarantino wants us to believe that there is both more and less to genre than critics would have us believe. In any case, his films do illustrate the pliant characteristics of genre.

Billy Wilder and the Dramedy

Bill Wilder is best known for having made Some Like It Hot (1958), one of the greatest farcical Situation Comedies and Sunset Boulevard (1950), one of the most realistic film noirs. He also made hybrid genre films, too dark to be described as a melodrama. Recently, these hybrid films have come to be called dramedies. Dramedies in their nature are useful examples of how elasticity in the narrative events and tone push a genre in the direction of a different, opposite genre.

Billy Wilder’s most celebrated dramedy is The Apartment (1960). C.C. Baxter, an insurance company employee, wants to advance up the corporate ladder and so he lends his apartment out for trysts to his superiors. He is ambitious but lonely.

He does move up the corporate ladder and is heartened to pursue the elevator girl at work. He asks her for a date. She never shows up because she is having an affair in his apartment with his boss. On Christmas day, she attempts suicide in his apartment. All will work out for C.C. Baxter in the end but the journey is about how much is lost when ambition displaces humanity as a way of life. Serious theme! Serious film and yet everything works out, except for his boss.

In Avanti, (1972), a corporate executive flies to Italy to bring back his father’s body for proper burial in the United States. There on an island in the Mediterranean, he discovers that his father has been coming to a resort for 20 years, to carry on an affair with another woman. He meets the woman’s daughter who has come to Iscia to recover her mother’s body. It seems the lovers chose to die together. The narrative highlights how the uptight “moral” main character, initially horrified by his father’s behavior, falls for the daughter who is anything but uptight. In the end, the main character and his new lover decide to bury the dead couple on Iscia and to carry on annually in their parents’ tradition. The film ends with their vows to meet next year in Iscia.

In Avanti as in The Apartment serious, even tragic events, suicide, infidelity mix with true love and values that transcend social convention. The dramedy typically navigates the space between the comedic and the dramatic.

We turn now to specific classic genres to illustrate ongoing flexibility and the narrative purposes served by that flexibility.

The Heist Film

The heist film is a more specific subset of the gangster film. If the gangster film follows the rise and fall of the career of the gangster, the heist film focuses on that job, late in the gangster’s career, that precipitates the fall. The heist itself can be seen as the final attempt to secure the benefits of crime, money or fame, whether the main character-gangster has been a success or never been. The degree of desperation in the narrative relates to the former status of the main character. The narrative itself will focus on the gathering of a gang or team to carry out the heist, the heist itself and the consequences of the heist. Generally, the difficulty of the heist will illustrate the skills of the main character and his team, or the lack thereof. Just as in the case of the gangster film, relational dimensions—family, father–son, love— will elaborate the emotional stakes attached to the meaning of the heist.

The classic heist film is best represented by John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle (1950). Robert Siodmak’s Criss Cross (1948) and Robert Wise’s Odds Against Tomorrow (1958) are equally powerful although Criss Cross veers toward film noir, using the femme fatale as the source of the main character’s fall, whereas racism within the gang is the source of the main character’s fall in Odds Against Tomorrow .

In Asphalt Jungle, the release from prison of Doc Riedenschneider (Sam Jaffe) kicks off the plot, the plan to rob a jewelry store. This heist promises great reward. This will be his last job, but he needs a gang and he needs finance. He finds both but his financier is a desperate “respectable” man (Louis Calhern) and plans to rob Doc once he has successfully robbed the jewelry store. The main character is Dix Handley, a hooligan who is honorable and is looking to use his share to buy back the family farm in Kentucky. His problem is he’s a compulsive gambler and consequently is always in debt.

The robbery succeeds with one member shot and dying (the explosives expert). Dix is shot by the “respectable” man’s hooligan. Doc is captured by the police, having admired a teenager dance to the jukebox he has been supplying with coins. He simply was too admiring of the young girl and so delayed leaving. Dix dies having reached his family’s former farm in Kentucky. Although the heist has succeeded, all its participants have failed. This is the classic narrative structure for the heist film.

The heist film has lent itself to shifts in tone. At one extreme it has been the basis for numerous comedic treatments from The Lavender Hill Mob (1951) to the darker The Ladykillers (1955) to A Fish called Wanda (1988). It’s not that the thieves get away with the material benefits of the heist. They don’t. But in each of these cases, it’s the characters who undo themselves rather than the abilities of law enforcement.

More believable in tone but more upbeat in outcome are films such as Robbery (1967), The Italian Job (1969), and The Bank Job (2008). Here, the heist gangs are at a distinct advantage. They succeed, but not all the members of the gang survive.

Mixing the comic and realist impulse in the heist film, we have the enormously popular Oceans 11 series made by Steven Soderbergh. Gang members do survive and manage to overcome a powerful antagonist, the head of the casino to be robbed. The skills of all parties are foregrounded. The heist is as elaborate as the Jules Dassin heist films Riffifi (1955) and Topkapi (1963). Tonally, Topkapi is similar to Oceans 11. It’s a fun take on a genre that in its classic form tends to the dark side.

Although the central features of the heist film putting together the gang, the difficult challenge of the robbery itself, and the outcome of the robbery for the participants are all a presence in all the above mentioned, there are differences. Those differences are essentially tonal; they focus on the nature of the relationships within the gang (loyalty vs. rivalry), motivations for the robbery, and variations in the outcome—negative being the expected, positive being the exception.

In tonal terms, writers such as Ben Maddow and John Huston in Asphalt Jungle and Walter Hill and Jim Thompson in The Getaway (1972) have given their films an existential layer embedded in the desperation of their main characters. Charles Crichton had no such ambitions in A Fish called Wanda or in The Lavender Hill Mob. That very range within the heist film best illustrates its flexibility as a genre.

The Thriller

In the current chapter in this book entitled “Working with Genre II: The melodrama and the thriller,” I write about the thriller without focusing on its flexibility. It’s useful for this chapter to briefly illustrate how very flexible this popular genre is.

Within the thriller category, there are three subcategories—the personal thriller, the political thriller, and the psychological thriller. The Hand that Rocks the Cradle (1992) and Breakdown (1997) are personal thrillers. Air Force One (1997) and Arlington Road (1999) are political thrillers while Repulsion (1965) and The Vanishing (1988), Dutch version are psychological thrillers.

Both the personal thriller and the political thriller lend themselves to tonal variance while the psychological thriller much less so. Consequently, a lighter approach to the political thriller is exemplified by Air Force One. Serious events occur, people are killed, but the president prevails over his kidnappers, is heroic, and saves the world from the next calamity. If this sounds like an Action-Adventure approach, it’s because it is.

Arlington Road on the other hand proceeds as a cautionary tale about home-grown terrorists. The main character dies, the terrorists are victorious, unusual in the political thriller.

In the personal thriller films such as The Firm (1993) and The Pelican Brief (1993) exemplify the earnest but ultimately successful main character’s effort to thwart powerful antagonists. These films represent the classic approach to the personal thriller. North by Northwest (1950) on the other hand represents an altogether lighter approach. At no point do we feel the main character played by Cary Grant is under threat. And his being put out by being mistaken for a spy is played as pique rather than anxiety or fear. Nor are the antagonists all that menacing. They are very much in keeping with the tongue-in-cheek quality of the rest of the film.

Reindeer Games (2000), written by Ehren Krueger, the screenwriter of Arlington Road is a dark personal thriller. A prison parolee (Ben Affleck) takes on the identity of a fellow prisoner who is killed in prison. On the outside, his new identity makes him a “prisoner” again. He is expected to help a group of criminal types rob a casino. Danger, betrayal, death awaits all. He escapes with his life but the question is about how untrustworthy and dangerous a road life really is.

The Science Fiction Film

At its heart, the science fiction film is an optimistic take on the struggle of Humanity vs. Technology. The mad scientist of Forbidden Planet (1955) has been replaced by the products of technology who can be malevolent ( The Matrix, 1999), benevolent ( The Rise of the Planet of the Apes, 2010) or both ( Terminator 2, 1991). Nevertheless, the core struggle in the science fiction film remains constant. Differences reside in tonal choices that imply the range from optimistic to pessimistic about the future and it’s here that the greatest flexibility is exercised in the varied treatments of the theme that unites the genre. One complication to that thematic treatment is the presence of an inexplicable greater force, a reference to religion that is a presence in some but not all science fiction films. It is certainly central in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1967) and in The Matrix.

Turning to the tonal treatments of character and plot in the genre, it’s best to use a film such as Gattaca (1997) as a baseline, representing a more realistic or humanistic treatment of the central theme.

Vincent Freeman’s (Ethan Hawke) blood test at birth suggests imperfection. He is likely to die of heart disease by age thirty. His brother Anton, genetically altered, is perfect and consequently privileged just as Vincent is destined to scrape by in life. But Vincent has willpower and he decides to “reach for the stars”; to become an astronaut. With the help of the perfect Jerome’s (Jude Law) blood he will try to pass as perfect. Jerome, a paraplegic, has the blood but not the will for perfection. Vincent’s success in Gattaca is about the triumph of will over science. The narrative treatment embraces Vincent’s humanity as it triumphs over the human flaws in Jerome and Anton. Gattaca is realistic in its treatment of emotional complexity as the x factor that trumps the y factor in genetics.

Taking an emotionally lively but more optimistic take on “character” in humans and non-humans, Star Trek (2009) presents the young James Kirk, a cadet, immature and overshadowed by his father. Can he fulfill his potential and become the Captain Kirk and Admiral Kirk, of his later life? The answer is with the help of the non-human Spock struggling to deal with emotion, the overemotional Kirk, will succeed.

J. J. Abrams, the director uses an Action-Adventure plot that compliments the humanness of both Kirk and Spock. Relative to Andrew Niccols’ Gattaca, where plot is not an equal partner in the narrative, Star Trek over-flows with emotion as well as the excitement of plot. The lighter treatment makes Star Trek far more accessible to a wider audience than does the more realistic Gattaca .

A third tonal option, to go dark, is best illustrated by the Ridley Scott film Blade Runner (1982). Deckard (Harrison Ford) is a blade runner. He tracks down replicants (technologically created nonhuman workers). They run away because they begin to exhibit human traits. Deckard is cynical but effective. The replicants want to extend their fixed short-term lives (the human equivalent of hubris). If they can reach Dr. Tyrell, the head of the Tyrell Corporation that created them, they believe they can extend their lives. Deckard’s job is to recognize the replicants (they look human) and destroy them. In doing so, however, he is losing his own humanity.

The complication for Deckard in Blade Runner is that he falls in love with Rachael (Sean Young) the most advanced version of the replicant. She too is destined for a short life (5 years). Will Deckard accept her fate and the fate of their relationship or not?

Blade Runner is a darker vision of the technology vs. humanity struggle. It’s as if humanity is not enough to overcome the predictable mortality of the replicants, the most advanced products of technology.

The war film is a genre that also exhibits a wide tonal range. Essentially, this story form focuses on the struggle of a character, civilian or military, caught in war. Will the character survive? Conversely, there are war films that pose the question, is there a war event or another person caught up in war, worth dying for? war films, particularly those made during a war, may take a patriotic position or an anti-war stance. This too becomes a motif in the war film. Another dimension, part of the advocacy of the war vs. the antagonism toward the war, drills down on the horror factor involved in combat. The physical as well as the psychological aspects of that horror also become elements in the narrative content of the war film.

One tonal category of the genre hones very close to the Adventure film. Here the main character and his comrades are heroes and in a cartoon-like sense, the enemy is disposable but not very challenging villains. Within this group there are comedic treatments of the narrative ( Kelly’s Heroes, 1970) and there are straightforward treatments for the narrative ( Where Eagles Dare, 1968, and The Guns of Navarone, 1961). Although a writer such as Carl Foreman in The Guns of Navarone, injects speeches that are anti-war, what remains memorable in this film are the heroic characters and the exciting plot. As a group, these films are enjoyable enactments of the most positive qualities of men in war—bravery, camaraderie, decency. The dark exists elsewhere. The best modern representation of this kind of war film is David O. Russell’s Three Kings (1999), set in the first Gulf war.

At the opposite extreme, there is the war film that focuses upon the overwhelming horror of war. Whether the focus is on the physical horror ( Letters from Iwo Jima, 2006, Come and See, 1985, or Full Metal Jacket, 1987), the intensity of these film experiences is the opposite of the entertaining adventurous, enjoyable aspects of the former group of war films. Quite the contrary, this narrative style focuses on the waste, the destruction, the dehumanization of war. What should also be mentioned is that they take the critique of war to a level far beyond the literary anti-war message of All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) and La Grande Illusion (1937). These films have a more visceral quality, ill-making as an antidote to the condition.

These dark interpretations are marked by graphic representations of killing and dying as well as endless amounts of cruelty and violence. Every heroic idea the viewer ever had about war is attacked, liquidated. These films represent war showing its ugliest face.

In between the romantic and the grotesque tonal options, there is a realistic option. Early versions of this style include Attack (1956) and Too Late the Hero (1970), both from Robert Aldrich, Hell is for Heroes (1962) from Don Siegel and Saving Private Ryan (1998) from Steven Spielberg.

Here the focus is on neither glorifying nor criticizing war. These films portray human behavior under conditions of war. In each of these films camaraderie, cowardice, bravery is on full display. The best and the worst of human behavior pours out under the pressure of combat. None of these films flinch from the violence of war or from the horrible representations of maiming and dying in battle. These films chronicle rather than editorialize. In their ways they have great narrative power.

Key here is that in their tonal variations each group presents a very different experience for their audience. No genre better illustrates the flexibility and the results of that flexibility within a genre than the war film.

The Romantic Comedy

On its surface the romantic comedy would seem the most straightforward of genres, a genre where two opposites meet, repel each other, attract each other, concluding with their getting together. In the past, national differences, class differences were the sources of comedy. More recently the romantic comedy has been subject to considerable exploration to make these differences both more modern as well as more realistic.

As a result recent romantic comedies have explored the romance of two misfits, the romance between two men or two women as well as the romance between two characters whose psychological profiles make them more suitable for darker genre treatments. In short, the romantic comedy has become the epitome of flexibility.

The classic romantic comedy from the director whose career focus was the romantic comedy is Ninotchka (1939). Directed by Ernst Lubitsch, co-written by Billy Wilder, Ninotchka set in Paris, is the story of the romance between an austere Communist (Greta Garbo) and a hedonistic Capitalist (Melvyn Douglas). Not even their deeply held opposing beliefs can trump biology.

Judd Apatow’s Knocked Up (2007) is a long way from Lubitsch. Lubitsch explored complex behavioral questions in his romantic comedies—is non-conformity an opportunity or a barrier to romance? ( Design for Living, 1933). Is profession an opportunity or a barrier to romance? ( Trouble in Paradise, 1932). What is more important to romance—public ambitions or secret desires? ( Shop around the Corner, 1940). Apatow is more interested in making his romantic couple opposites and psychologically ill-suited. As a result in films such as Knocked Up (2007), the Apatow produced Forgetting Sarah Marshall (2008) and I Love You, Man (2009), he is exploring the less attractive features of men. In Knocked Up, an immature stoner, Ben (Seth Rogen) has a one-night stand with a drunken beauty, Allison (Katherine Heigl). Her consequent pregnancy poses the questions—what will she do? What will he do? And the larger question—Can such a refined beautiful young woman fall for a slob? He changes and so does she.

In Forgetting Sarah Marshall, it’s the vulnerability of the male that is the barrier. At the beginning of the narrative the main character, Peter (Jason Segel) is abandoned by his famous girlfriend, Sarah Marshall (Kristen Bell). He falls apart, follows her to Hawaii, and there finds Rachel (Mila Kunis). She too is vulnerable. Nevertheless, these two wounded people eventually get together.

In I Love You, Man the romantic story is between two men. Peter (Paul Rudd) is engaged but friendless. He has a “female” side. He likes to hang out with his fiancée and be one of the girls. Who will be his best man at the wedding? He sets out to find a friend and he does. Sydney (Jason Segel) is a man’s man. The rest of the narrative is their on–off relationship. The film ends with the two men embracing at Peter’s wedding.

All three of these Apatow productions focus on male behavior— immature, insecure, gender blurring. By doing so, Apatow has enlarged the palate for the romantic comedy, making it more modern and more psychologically complex.

Other examples of flexibility include 500 Days of Summer (2009), a film about the most romantic guy (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) falls for a young woman (Zooey Deschanel) who doesn’t believe in love. Needless to say the relationship fails based on ideological incompatibility. At the opposite extreme is Enchanted (2007) where a New York divorce lawyer (Patrick Dempsey) who no longer believes in love falls for a fairy princess (Amy Adams) who is banished from her fantasyland to New York. She of course believes in love. The results are as you would expect in a Disney production.

The Biography Film

The biography film focuses upon a famous person. Whether the person is a scientist or a soldier, the task of the writer is to humanize a revered or reviled figure. This means the plot will focus on what made them famous while the character layer, the relational story, will humanize and emotionalize our relationship with the character. The 1930s were the classic period for the biography film, with the Warner Brothers Studio as the creative home for these films. Emile Zola, Louis Pasteur, Dr. Ehrlich, Juarez, all were subjects. More recently Gandhi, T. E. Lawrence, Jackson Pollack have been the basis for biography films. Generally, these films have been admiring of their subjects.

The genre has been stretched by the exploration of the weaknesses, flaws, and indeed the underside of characters that have captured the public imagination. It’s here within the darker interpretations that different tonal treatments, less romanticized, have yielded a very different style of biography film. They also demonstrate that tonal variation yields useful options for the biography film.

When the classic biography adopts the melodrama option positioning the main character as a powerless character seeking power (or acknowledgement) from the power structure, the plot is the vehicle or means to make the main character heroic. Where the main character is less admirable, he or she needs to be surrounded by a character population that is even less admirable. Irony, humor, and exaggerations can push such a group of characters away from heroism toward satire. In short, distance us or provide enough distance from the main character to judge him rather than feel sorry for him.

The Hoax (2007) directed by Lasse Hallstrom and written by William Wheeler, is about Clifford Irving, the writer who in the 1970s claimed to be the official biographer of Howard Hughes. After release from prison he wrote The Hoax, a biography of his literary hoax.

Clifford Irving (Richard Gere), a modestly successful writer, loses a promised contract from McGraw-Hill, the publisher, as the story opens. Simultaneously his furniture is being repossessed and his marriage is as shaky as his finances. He needs a home run to solve his situation and to solve his ambition. He comes up with the idea of a biography of one of the world’s richest men, Howard Hughes. The fact that Hughes is a recluse, in hiding from a damaging lawsuit, is an encouragement.

The narrative is a cliffhanger. Can this disreputable almost-been of a writer pull off this high wire hoax? He almost does. Wheeler, the writer creates a view of publishers and publishing that is far more greedy and manipulative than Clifford Irving. He also uses Clifford’s co-writer, Richard (Alfred Molina) for humor. The surrounding character population, even those who help Irving—his mistress Nina (Julie Delpy), his wife Edith (Marcia Gay Harden), and Noah Dietrich (Eli Wallach), an associate of Hughes—are callow and shallow. As a consequence, the tone of The Hoax is smart and ironic. Wheeler and Hallstrom push the narrative toward a comment on the seventies. This is not quite as powerful as the portrait of Irving as a grandiose scoundrel. By making the character population even more grandiose and nasty, The Hoax becomes the anti-heroic biography film.

Another narrative strategy used to make the reprehensible main character of the biography film accessible is to use an on-screen narrator, a much more sympathetic character, as a guide. Both The Last King of Scotland (2006) and The Devil’s Double (2011) use this strategy. In The Last King of Scotland, the subject is Idi Amin, the dictator of Uganda in the 1970s. His mass murder of his people scandalized the international community. The guide, Peter Morgan, the writer uses Amin’s personal physician, Dr. Nicholas Garragan (James McAvoy). In The Devil’s Double the subject is Uday Hussein, the murderous son of Saddam Hussein, the dictator of Iraq. The narrative guide is Latif, his double (Dominic Cooper). In both cases, there is considerable contrast between our guide and the biographical subject. Dr. Garragan is adventurous and engaged whereas Amin is primitive and given to impulsive action. Both characters have an appealing edge to them making each less than predictable. Uday Hussein and his double Latif are also opposites with Latif more conventionally good and Uday more conventionally evil. Uday is also impulsive, violent, and paranoid. He’s dangerous in the same way Amin is dangerous. But Amin as played by Forest Whitaker has a sense of power that is not a presence in the Uday character.

There are also tonal differences between the two films. Kevin McDonald, the director of The Last King of Scotland opts for a sensuality that energizes both Amin and his doctor. When this sensuality links up with power, the violence in the film seems dangerous and unstable.

Lee Tamahori and his writer Michael Thomas opt to emphasize Uday’s instability. He seems far more a comic character mired in unintelligence. The result is to trivialize Uday’s acts of violence. As a result the narrative in general seems to shrink. These narrative choices have clear consequences for the impact of the overall narrative.

Other recent biography films that deploy the idea of an innocent narrator or guide include The Last Station (2009), focusing on Leo Tolstoy’s last years; and My Week with Marilyn, a film about the making of The Princess and the Showgirl in England. In both films the narrator affords an easier entry into the complex subjects of these two biography films.

The Melodrama

Much attention will be given in a later chapter on melodrama. The focus here is on the classic treatment of melodrama. In this chapter; given our focus on the flexibility of genre, we will look to alternative treatments of the genre, treatments that change the mix of the narrative tools to yield a surprising experience that is no less true to the genre. To contextualize these “new” melodramas, an old melodrama will serve as a useful referent point.

A Place in the Sun (1951) directed by George Steven, written by Michael Wilson and Harry Brown, is based on the Theodore Dreiser 1920s novel, An American Tragedy. George Eastman (Montgomery Clift) travels east to take a job at his rich uncle’s factory. He is uneducated but wants to move ahead. At the factory, he falls for a co-worker, Alice Tripp (Shelley Winters). He gets her pregnant. At a party at his uncle’s house, a rich beauty, Angela Vickers (Elizabeth Taylor) falls in love with him.

He chooses to be with Angela. But to do so he chooses to get rid of Alice. He takes her out on a boat to drown her, but he can’t do it. Afraid, she stands up and falls from the boat. She drowns. He is brought to trial for the drowning. He is found guilty and at the end of the narrative he is executed.

Given that he only thought to kill Alice but didn’t actually kill her, he is executed for his intentions rather than his actions. Another interpretation is that by choosing Angel over Alice, he has expressed his desire to get ahead and he is punished in the end for that desire. A Place in the Sun is in every sense the classical melodrama—a struggle for power whose result in this case, is tragic.

Fatih Akin’s The Edge of Heaven (2008) alters the structure of the narrative, but it too at its heart is a struggle for power ending with tragic results.

Akin divides the narrative into three chapters, titled Yeter’s Death, Lotte’s Death, and The Edge of Heaven. Two stories focus on a relationship that ends in death. The third story focuses on the forgiveness/acceptance of one generation for the behavior of the elder in one case, and of the younger in another.

The character population divides into three families, two Turkish and one German. In each case, there is a single parent of the same gender. The three younger characters are the main characters. Each shares the premise— am I traditional or am I modern? If I am traditional, I am intolerant; if I am modern, I am tolerant. Tolerance means acceptance across religious, cultural, and gender lines.

Yeter’s Death focuses on the relationship of two Turks living in Germany. Yeter is a prostitute. Ali Aksu is retired. He has a son Najat, a professor of German. Nejat is one of the main characters. Ali asks Yeter to live with him, be his exclusively. Harrassed by two religious Muslims, Yeter sees Ali’s offer as an escape from them. But Ali becomes possessive. When he has a heart attack he fears his son has slept with Yeter. He hits Yeter. She dies. Ali is deported back to Turkey.

Lotte’s Death focuses on Yeter’s daughter, Ayten. A radical in Turkey, Ayten is jailed. Before imprisonment she hides a pistol. Intimidated, Ayten names names and is released. She goes to Germany as an illegal. There she can’t get on with the radical men who are her fellow radicals. She looks for her mother (who had said she worked selling shoes in Bremen). Not finding her, she meets Lotte at the university. They begin a relationship. Lotte, very liberal, invites Ayten to live with her. But Lotte’s mother, Susanne, doesn’t approve. They are picked up by the authorities who discover Ayten is an illegal. When Ayten is deported to Turkey, Lotte follows. At a prison visit in Turkey, Ayten alerts Lotte to the danger of the gun. She asks Lotte to retrieve the gun. She does, but her bag carrying the gun is stolen by street kids. One of them uses the gun, shooting Lotte. This ends with Lotte’s body being returned to Germany.

The Edge of Heaven focuses on Nejat who has never forgiven his father. He goes to Istanbul to find Ayten. He wants to pay for her schooling. He doesn’t find her. He buys a German bookshop and stays.

Suzanne, Lotte’s mother, remorseful, comes to Istanbul to try to secure Ayten’s freedom. She rents a room from Nejat. She visits Ayten. Her behavior moves Nejat. The film ends with his journey to reconcile with his father.

Each of the main characters is forced to deal with their anger with their parents. It’s the parents who seem to be imprisoned by the values of tradition. It’s the older generation—Yeter, Ali, and Susanne who suffer the tragedies that emanate from their rigid beliefs.

The question for Charlotte, Ayten, and Nejat is whether they wish to replicate their parents’ rigidity. Each is angry and yet in the end each must find a way to forgive. Nejat must forgive his father, Ayten must forgive Susanne, and by doing so, forgive her own mother. Lotte and Yeter are the casualties of the violence that is at the center of traditional male values. They have consequences for women. They also have consequences for the men. Nejat chooses to be a modern man and to forgive his traditional father.

By using multiple main characters and a structure that is essentially three short films each with its own dramatic arc, Akin has deepened the narrative map of his melodrama. Rather than making it about a young person in a “parental” power structure, or a Turk in a German world, Akin has created a layered melodrama. Because there is no clear antagonist and because the main characters don’t necessarily struggle deeply as their own antagonists, Akin has allowed the more general notion that it’s the world they live in that is antagonistic to its young.

Asghar Farhadi in his film A Separation (2011) seems equally capable of creating a large palate for his intimate story of two families in contemporary Teheran. As in The Edge of Heaven, the traditional vs. modern, the young vs. the old, the secular vs. the religious, the female vs. the male; allow for an enormous amount of conflict in A Separation .

The middle class family in A Separation has one child, a girl. Simin, the wife, wants to leave Iran for the sake of their daughter and her future. The husband, Nader, does not. He must stay to care for his elderly father, already beset by Alzheimer’s disease. She files for divorce but is disallowed from taking their daughter abroad without Nader’s permission. Stalemate.

The working class family enters the story. Razieh, the wife, a religious woman, has a young daughter and an unemployed husband. She takes a job to mind Nader’s father. Its a very uncomfortable job as Razieh must wash and touch the old man in a manner forbidden to a religious woman.

A complication is Razieh’s pregnancy. Should she have a child or an abortion given her economic situation? One day she goes to the doctor, leaving Nader’s father tied to the bed. Nader finds his father in this state, argues, and shoves Razieh on her return. She is rushed to the hospital. She loses the baby. Her unemployed husband sues Nader for manslaughter. A judge will decide Nader’s fate.

A negotiation between the two families around blood money results in a settlement that would bankrupt Nader but keep him from jail. At the last moment, the religious Razieh confesses the child didn’t die from Nader’s actions. He is relieved. Now the danger is that Razieh’s husband in his desperation will kill her or himself. The narrative ends with Nader and Simin awaiting a judge’s decision about which of them will have custody of their daughter, a decision the judge leaves to the daughter.

A Separation begins at a critical moment in the life of one family and ends at a crisis point in the lives of two families. Although each of the six members of each family is trying to act in the interest of their family, they can’t seem to help the members of their family. Although the two men seem rigid or harsh in their personal actions, Farhadi does not position them as antagonists. The members of each family suffer, not from the same causes, they suffer from being unable to find a way out of their suffering.

Each action, keeping a sick parent at home, trying to find financial solvency for the family, trying to secure a future for one’s child, is simply a goal. The fact that there is no resolution emanating from trying to secure that goal, seems to go to the core of what this melodrama is about. Farhadi could have called his film No Way Out, and it would seem appropriate.

These characters attempt as do all main characters in the melodrama to secure power to improve their lives. In doing so they fail. So far these characters share the fate of their fellow main characters in classic melodramas.

What is different about A Separation is that the power these characters seek seems beyond the family. None of these characters seem to be able to help one another. The family unit, generally presented as the power grid in films such as Once Were Warriors or The Heiress is not the power grid in A Separation. Power seems to reside in a judge, a policeman, an official beyond the family. The result in A Separation is no resolution for these characters. They are caught in a system where family members are powerless. For all their efforts, the character population in A Separation are left suspended in conflict. This unbearable situation, the idea that there is no resolution for these characters, leaves the audience of A Separation to ponder whether life for these two families is sustainable and if it is, at what cost. Farhadi has fashioned a melodrama without resolution and in doing so he has taken his audience into the hell that is life for these two families. But he has done so without losing his empathy for the members of these two families, a remarkable achievement.