Chapter 6

Managing to Care

Design and Implementation of Patient-Centered Care Management Teams

This study was funded in part by NSF grant 0719257, The Effect of Social Networks and Team Climate on Team Innovation and Consumer Outcomes in Health Care Teams.

Douglas R. Wholey, Xi Zhu, David Knoke, Pri Shah and Katie M. White

Learning Objectives

- Define care management teams, distinguishing them from care provider teams and clinics.

- Understand the role of care management teams in improving patient-centered and -coordinated care.

- Identify the general issues, principles, and features pertinent to the design and implementation of effective care management teams.

- Examine a conceptual model for care management team implementation based on key process factors, using a context-mechanism-outcome configuration approach to conceptualize care management team design, performance, and evaluation.

- Apply a network theory perspective to the consideration of care teams and team design.

The word team in health care is a catch-all term for many different types of care delivery units, such as surgical teams, primary care clinics, and patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs). These units often represent different conceptualizations of teams and organizing principles. As such, generic theories of teams may not apply equally well to each of the different entities categorized as teams in the medical setting. Thus, the goal of this chapter is to develop a theory of care management teams that explicates their functions in improving patient-centered and coordinated care. In pursuit of this goal, we examine the issues that need to be addressed to design and implement effective care management teams, especially those serving patients with chronic and complex conditions. Our central premise is that care management teams themselves are causal mechanisms whose functioning is influenced by their context and that an effective conceptualization of their context-mechanism-outcome configuration (CMOc) will improve the implementation of care management teams (Pawson, 2003; Pawson and Manzano-Santaella, 2012; Pawson and Tilley, 1997).

Care Team Conceptualizations

This chapter begins by contrasting care management teams with two other types of care teams: care provider teams and clinics (table 6.1). Defining these different types of care teams is important because it facilitates cumulative theory development and research. We then further distinguish each type of team and the organizational context within which each is embedded.

Table 6.1 Definitions and Key Characteristics of Care Teams

| Care Provider Team | Care Management Team | Clinic | |

| Definition | A virtual network of all the providers who deliver care and support during the patient's trajectory through the health care system | A transdisciplinary team organized to manage and coordinate care tailored to the patient's circumstance | A functional unit organized to provide similar services to multiple patients |

| Composition | Providers from different units, clinics, and organizations who provide care to the same patient | Providers, potentially from different units, clinics, and organizations, who provide care to the same set of patients | Providers within the same unit, clinic, and organization who provide care to a flux of patients |

| Boundary | Unclear boundary | Clear or potentially clear boundary | Clear boundary defined within an organizational unit |

| Interdependence and collective responsibility | Low interdependence, collective responsibility not assessable | High interdependence, collective responsibility potentially assessable | High interdependence |

| Stability | Naturally constructed around individual patients, virtual and unstable | Designed and organized to serve a set of individual patients; moderately stable to stable | Stable |

| Team identity | No team identity | Clear team identity | No team identity, clear professional and organizational identities |

| Focus | Patient focus, individual patient outcomes | Patient focus, individual patient outcomes | Functional focus, aggregate clinical outcomes |

| Coordination roles | Patients, caregivers, often primary care providers | Care management team | Unclear |

| Effectiveness in care coordination | Variable, depending on the complexity of care needs and the effectiveness of the care coordinator | High | Low |

Care provider teams consist of all the providers and caregivers who deliver care and support for a patient during his or her trajectory through the health care system (Strauss et al., 1985). As a result, members of a care provider team are unlikely to be colocated within the same organizational unit or even organization; rather, they form a virtual network spanning multiple organizations. For example, the care provider team for a patient with cancer may include an oncologist, a palliative care specialist, chemotherapy nurses, radiotherapists, a hospice specialist, a primary care provider, spiritual advisers, and social workers. Because they are based on the specific and changing needs of patients, care provider teams are idiosyncratic and dynamic, reflecting a patient's history, interests, and narrative. Furthermore, in care provider teams, the patients are the experts in their own biographies, social contexts, and needs, and they develop knowledge in medicine and health care as their trajectories unfold. As such, they focus on their own outcomes and see the care they receive from the perspective of how it assists them in reaching their goals.

In contrast, clinics are functional teams organized around a particular type of care (e.g., primary care, palliative care, oncology). In the case of primary or specialty care, the clinic's focus is on providing a set of similar services to multiple patients. Although the gains from organizing professionals by functional areas can be valuable, the losses involve the difficulty in coordinating and integrating actions across clinics. For example, clinics' functional focus may lead to subgoal optimization, a behavior that optimizes goals of individual clinics that conflict with those of the enterprise (March and Simon, 1958). It may also lead to clinics' developing distinctive cultures and languages that can become barriers for interacting with other clinics (Bechky, 2003; Tajfel, 1982). Subgoal optimization and cultural differences are barriers to the development of infrastructures and communication mechanisms among different clinics, resulting in clinics that are often organized as networks of providers connected within their own units but isolated from one another. In addition, clinics are experts in medical diagnostics and procedures, striving to provide their expert services at a high standard. Public reporting of clinics' quality outcomes has reinforced this aim by emphasizing aggregate clinical outcomes rather than patients' biographical outcomes (such as how well medical care assists patients in reaching individual health goals in their biographic contexts).

The Coordination Problem

For both care provider teams and clinics, the issue of coordinating care for patients is problematic. Clinics' focus on function and aggregate clinical outcomes impedes coordination efforts. Similarly, communication and coordination among care provider team members are likely to be minimal given the different roles of the team members. Furthermore, the differences in expertise and goals between care provider teams and clinics contribute to the difficulty in simultaneously achieving high performance for both. Thus, the organizing challenge is to coordinate activities among all providers to offer seamless care specifically tailored to the needs of each patient.

There are three broad solutions to the coordination problem. The first is for patients and caregivers to perform the coordination role. This occurs for patients who seek to control their health care, can assemble the information about their health conditions, are aware of their needs, and can adequately communicate such information with all providers. Although coordinating care may be burdensome, it can ensure that care matches the patient's preferences and biographies, and it can also be rewarding for caregivers. In this situation, the role of providers is to support the patient and caregiver in care coordination.

The second solution is to use interorganizational networks to facilitate coordination, such as mental health networks (Provan and Milward, 1995) or palliative care networks (for example, Bainbridge et al., 2010). Coordinating through interorganizational networks can be accomplished by investing in tools that increase the ability of organizations to share information and by establishing boundary-spanning roles (Faraj and Yan, 2009) and objects such as care plans (Bechky, 2003; Nicolini, Mengis, and Swan, 2012). Interorganizational coordination can also be accomplished by standardizing provider roles and care pathways across organizations (Deneckere et al., 2012). Accomplishing coordination in interorganizational networks is likely to require significant investment in information technology as well as the willingness of providers and organizations to adapt their practices to network standards. Justifying this investment requires a high number of clients seen in common in order to achieve scale economies.

The third solution is to implement roles or teams that act as a patient's agent in coordinating care. As the need for both service provision and coordination increases, care management teams are favored, providing services and coordinating care tailored to patients' circumstances with teams of interprofessional members. Examples of care management teams include carve-out programs for specific conditions (Blumenthal and Buntin, 1998), assertive community treatment (ACT) teams for individuals with severe mental illness (Monroe-DeVita, Morse, and Bond, 2012; Stein and Santos, 1998), chronic care teams (Bodenheimer, Wagner, and Grumbach, 2002; Wagner, 2000), and PCMHs (Alexander and Bae, 2012; Stange et al., 2010) for individuals with multimorbidity (Valderas et al., 2009). A strength of coordinating with a care management team rather than an interorganizational network is that this team provides patients with a relational home and an expert adviser in navigating the care provider network. This is likely to be beneficial in situations where the effectiveness of delivery depends on a strong personal relationship such as in motivational interviewing (Hettema, Steele, and Miller, 2005; Miller and Rose, 2009).

Defining Care Management Teams

A theory of care management teams requires a definition that clearly distinguishes them from care provider teams and clinics. These teams are often imprecisely defined (Alexander and Bae, 2012; Vest et al., 2010). In fact, Wagner's (2000) definition of patient care teams can be interpreted as either a care provider team or a care management team. For example, the following segment of the definition suggests a care-management-team interpretation: “A patient care team is a group of diverse clinicians who communicate with each other regularly about the care of a defined group of patients and participate in that care” (Wagner, 2000, p. 569). However, this next segment of the definition suggests a care-provider-team interpretation:

Effective team care for chronic illness often involves professionals outside the group of individuals working in a single practice; it may involve multiple practices—for example, primary and specialist care—or it may involve multiple organisations, such as a general practice and a community agency. Teams that cross practice or organisational boundaries may create communication and administrative nightmares but are essential for optimizing care for many patients. (Wagner, 2000, p. 569)

We define care management teams as “real” teams designed to provide and coordinate patient-centered care. Wageman and colleagues (2005) identify three core features of real teams: clear membership boundaries, interdependence that fosters collective responsibility for assessable outcomes, and membership stability. Care management teams should be designed to have well-defined boundaries, be held collectively accountable for patient care and outcomes, be highly interdependent, and have stable membership (Monroe-DeVita et al., 2012; Monroe-DeVita, Teague, and Moser, 2011).

In contrast, care provider teams are not real teams because they are unlikely to have clear boundaries, high interdependence among all members of the network, collective responsibility, or membership stability. Care provider teams also differ from care management teams in terms of team identity coordination roles, and coordination effectiveness. Whereas care provider teams lack a team identity, exhibit variable effectiveness in care coordination, and assign coordination roles to patients, caregivers, and primary care providers, care management teams maintain a clear team identity, exhibit high effectiveness in care coordination, and assign coordination roles to the care management team.

In contrast to clinics, which have a functional focus, care management teams have a patient focus. Furthermore, these teams differ from clinics in their composition of providers, team identity, coordination roles, and coordination effectiveness. Clinics are composed of providers within the same unit, clinic, and organization; maintain professional and organizational identities rather than a team identity; exhibit low effectiveness in care coordination; and lack clear coordination roles. Care management teams are composed of providers from potentially different units, clinics, and organizations; maintain a clear team identity; are highly effective in coordinating care; and rely on the care management team as a whole to coordinate care (table 6.1).

The next section discusses care management teams as a mechanism affected by the context they operate in using a context-mechanism-outcome configuration (CMOc) approach (Pawson, 2003; Pawson and Manzano-Santaella, 2012; Pawson and Tilley, 1997). This section is followed by a discussion of key issues in designing care management teams and then by a conceptual model of care management team implementation examining determinants of implementation outcomes.

Care Management Team Context-Mechanism-Outcome Configurations

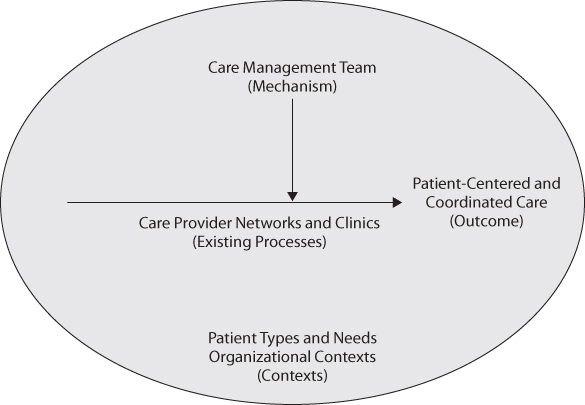

Care management teams are, in effect, interventions intended to bridge the gap between the reality of clinic-based care delivery systems and the need for team-based care coordination. Care management team design and evaluation can be articulated using the CMOc framework (Pawson and Tilley, 1997), in which “the action of a particular mechanism in a particular context will generate a particular outcome pattern” (Pawson and Manzano-Santaella, 2012, p. 184). These teams are mechanisms designed to produce patient-centered and coordinated care for patients with complex needs. The functioning of care management team mechanisms is influenced by its context. Figure 6.1 is a general CMOc for care management teams (Pawson, 2003; Pawson and Manzano-Santaella, 2012; Pawson and Tilley, 1997).

Figure 6.1 A Care Management Team CMOc Framework

The contexts of care management teams are complex. The first source of complexity is the complicated, evolving, and emergent medical conditions of patients. Teams have to be prepared to respond to new circumstances by providing services themselves or supporting and coordinating services provided outside the team. This complexity means that teams have to maintain high situational awareness, staying aware of the current situation and anticipating future changes in order to support patients effectively (Endsley, 2000). A second source of complexity comes from supporting providers and integrating care across many organizational settings. A third source is that care management teams are often embedded in sponsor organizations such as clinics, health systems, or county-level entities that create the immediate context for the care management team and provide its infrastructure.

Key contextual attributes for care management teams include:

- A compelling direction; clear and measurable specification of what the team is accountable for in terms of outcomes, productivity, and staff's quality of work life and a statement of the team's purpose (Wageman et al., 2005). This purpose should describe the care management team's fundamental goal—the primary reason for the team's existence, such as maximizing the quality of later-life care or maximizing the recovery of individuals with mental illness (Sheedy and Whitter, 2009). The primary means to achieve the goal should also be specified (e.g., shared decision making, service integration). These goals and means are necessary to guide effective team design.

- Infrastructure and resources necessary to perform their tasks and responsibilities.

- Delegation of the responsibility and control over their self-organization (Ostrom, 1990). Put differently, this attribute entails guarding against micromanagement by health systems or sponsors and promoting team commitment to operational decisions. This delegation empowers the team to take control of its responsibilities and facilitates its ability to integrate the knowledge it has gathered effectively (Haas, 2006).

- Incentives that induce outcome interdependence, such as the degree that rewards are shared by the entire care management team (Pearsall, Christian, and Ellis, 2010; Town et al., 2004; Van der Vegt, Emans, and Van de Vliert, 1998; Wageman, 1995).

These contextual attributes are causal mechanisms that affect the functioning of care management teams because they moderate the effect of care management team design. For example, when a team's sponsor organization makes staffing, programmatic, and budget decisions with little input from the team, the team will likely become disengaged. The more these contextual attributes are in place, the more likely is the program embodied in the care management team to be effective in producing desired outcomes.

Designing Care Management Teams

Because the contexts for care management teams vary significantly across patient groups (e.g., chronic heart failure patients versus severe mental illness patients) and thus demand different clinical details in team design, we focus our discussion on general care management team design features such as structural and process features. These general principles need to be adapted to the specific situations and conditions of each team.

The Role of Fidelity

Fidelityfidelity is the assurance that the theory implicit in an intervention has been implemented as intended (Mowbray et al., 2003). The promise that a specific team design will result in desired outcomes is warranted only when the intervention is explicitly laid out in theory and is faithfully implemented in practice. In other words, designing care management teams involves developing explicit fidelity measures to assess how well those teams work as intended. Fidelity measures can be grouped into structural-process characteristics and clinical aspects (Bond et al., 2005). Using ACT teams as an example, structural-process fidelity measures include characteristics such as the mix of health professionals a team should have, workload defined by the number of patients per team member, information management such as regular care planning and having care plans on file, coordination mechanisms such as daily team meetings, and structures that support individualized care and quality improvement (Bond et al., 2009; Monroe-DeVita et al., 2011). Clinical fidelity measures include specifics about services and interventions that the teams should provide, such as motivational interviewing (Burke, Arkowitz, and Menchola, 2003; Madson and Campbell, 2006; Madson, Loignon, and Lane, 2009) and supported employment (Bond, Becker, and Drake, 2011).

Developing fidelity measures is beneficial for a number of reasons:

- It forces a clear statement of each of the care management team's design features, which increases the rigor of the design.

- It supports standardization and provides concrete guidance for implementation.

- It describes what should occur if the team is implemented correctly.

- It supports the assessment of how well each design feature is implemented.

- It supports the assessment of the relationship between the design features and team performance.

- It identifies gaps in implementation and suggests solutions to fix the gaps.

- It supports the long-term diffusion of the care management team.

The fidelity measures for a care management team need to be developed to fit its specific theoretical underpinnings (Schoenwald et al., 2011). The specification of fidelity measures should be based on a strong theoretical foundation so that it allows the examination of causal mechanisms as recommended by realistic evaluation, an approach that asks “what works for whom in what circumstances … and why” (Pawson and Manzano-Santaella, 2012, p. 178). Such a foundation reduces the chance of applying ad hoc definitions of an intervention in different studies and implementations and it supports cumulative research. A review of PCMHs, for example, found that “multiple organizations and individuals have notable variations in their definitions of the medical home” (Vest et al., 2010). This variation suggests that research on PCMHs may be difficult to accumulate because researchers are not studying the same intervention.

The fidelity specification for care management teams should start with the definition of a team as

(a) two or more individuals who (b) socially interact (face-to-face or, increasingly, virtually); (c) possess one or more common goals; (d) are brought together to perform organizationally relevant tasks; (e) exhibit interdependencies with respect to workflow, goals, and outcomes; (f) have different roles and responsibilities; and (g) are together embedded in an encompassing organizational system, with boundaries and linkages to the broader system context and task environment. (Kozlowski and Ilgen, 2006, p. 79)

The discussion below focuses on specifying fidelity measures for care management teams along with key team design features (Wageman et al., 2005).

A Real Team

As noted, a care management team should be a real team with clear boundaries, high interdependence, and membership stability (Wageman et al., 2005). The clear boundaries are necessary to identify who is jointly accountable for the team's outcome. Having clear boundaries does not mean that an individual cannot be a member of multiple teams. A primary physician may be a member of a dozen PCMHs. In ACT teams, a psychiatrist is usually a member of two teams. The important point is that a provider should see herself as a distinct member of a specific team and understand her role on that team despite multiple team membership. Furthermore, every team member should be able to identify who is and is not on the team. The risk of not making membership clear is that as multiple team membership increases, team members are less likely to share a common identification (O'Leary, Mortensen, and Woolley, 2011), which attenuates the effect of accountability.

Interdependence among team members means that they need to work closely together in performing tasks (Thompson, 1967; Van de Ven, Delbecq, and Koenig, 1976), which differentiates teams from individuals who are colocated in the same space performing independent tasks. Interdependence creates a sense of shared purpose, a motivational factor for information sharing (De Dreu, 2007). Interdependence facilitates coordination through both process mechanisms, such as team meetings, information sharing, and decision making, and cognitive mechanisms, such as the team mental model and transactive memory. Stability of membership implies that care management teams should be more than temporary ad hoc teams assembled for the duration of a specific activity, such as surgical teams or flight crews. Stability fosters the understanding of patients and their contexts over time that is necessary for situational awareness and patient-centered care. Stability also contributes to cognitive coordination mechanisms because such mechanisms usually take a long time to develop.

Team Size and Workload

Ideally a care management team should have relatively few members, from four to twelve people. This limited range allows key skills and services to be included while avoiding scope diseconomies caused by larger teams fragmenting into subgroups. The limited team size facilitates high levels of overall team interdependence by limiting the number of possible work relationships in the team. It also makes it feasible to define clear team boundaries and assign accountability. In practice, larger teams, such as those incorporating entire clinics, often fragment into subgroups, which may impede team functioning by reducing interdependence and blurring team boundaries and responsibilities.

The workload of a care management team—the number of patients per team member—will be a function of the care demands posed by its target patients. For example, the workload for ACT teams is designed to be around ten clients per team member (Teague, Bond, and Drake, 1998). This workload reflects the high complexity and uncertainty of the clients (e.g., individuals with severe mental illness) and the nature of the services (e.g., services delivered in community or clients who are visited frequently). The workload for PCMH teams is likely to be larger because the patient population will be a mix of patients in both fairly stable condition and in crises. In Aetna's embedded case managers (ECM) program (Hostetter, 2010), a patient-centered primary care program, an ECM can support a population of around two thousand Medicare patients because relatively few patients, around seventy to eighty, are in a crisis mode that requires intensive attention at any given time. The number of patients a palliative care team can support will similarly be determined by the varying demands of the patients and caregivers in the population served.

Task Scope and Team Composition

Three steps determine the task scope for a care management team. First, all the tasks that need to be performed to create value for the target patients should be specified. Second, the task mix can be used to identify the occupations necessary to perform those tasks. Third, the team has to determine which services it should directly provide and which should be provided externally. Because tasks are the functions that a team must perform to achieve its goals, they are a logical starting point for team design. Once the tasks are determined, the skills required by the individuals to perform tasks and the occupations of those individuals can be determined. The last step is necessary to limit team size and focus the team on the most important tasks.

Initially focusing on tasks rather than occupations strengthens team design because it focuses on the functions that must be accomplished rather than the person performing the functions. Focusing on occupations—the types of skills that providers have—can result in designing the team in terms of provider skills rather than the types of services that patients need. In the case of PCMHs, framing the team as being led by a primary care physician may lead to an ineffective design. In contrast, focusing on tasks and patient needs can result in identifying the occupation best able to perform the tasks and meet patient needs. The design of a coordinated care clinic (CCC) by Hennepin County Medical Center (HCMC) reflects a task-driven team design (Johnson et al., 2012). HCMC is a safety-net hospital in Minnesota that serves a population of high-risk patients who are medically complex and have significant mental health and social issues, including unstable housing and lack of social support. The need to address mental health and social issues is reflected in the CCC team design, which includes a full-time nurse practitioner, a Registered Nurse care coordinator, a social worker, a half-time physician, a pharmacist, a chemical dependency counselor, and a one-tenth-time clinical psychologist. The team's occupational mix is designed to fit the complex set of tasks required for patients.

The decision about which services the team should supply versus those supplied by external providers will ultimately determine a care management team's composition. Choosing among occupations is difficult because patients with complex conditions often need a wide variety of services. Three factors may influence this decision: team size, task importance, and opportunity cost. An appropriate team size can help a care management team maintain a high level of interdependence among key occupations needed for patient care. It should not be excessively large because the size of the team is negatively related to the level of interdependence. It should not be too small either so as to exclude key occupations. Fidelity measures for ACT teams, for example, suggest that team size should be in the range of eight to twelve team members and include key occupations such as psychiatrist, nurse, substance abuse specialist, and vocational specialist. The importance of a task can be characterized in terms of the prevalence of it. In principle, occupations performing more important tasks should have priority for inclusion on the team. This principle, however, needs to be conjoined with the consideration of opportunity costs of not including other occupations. The accessibility of external services and the losses in coordination efficiency both contribute to the opportunity cost.

Division of Labor

Division of labor determines which team member, group of members, or entire team perform which task. The result is a matrix of the assignment of individuals to tasks. Tasks can be classified by the levels of skill required to perform them: generic, enhanced, and specialized (National End of Life Care Programme, 2012). Generic tasks are those that can be performed by any member of the care management team. In ACT teams, for example, a generic task is “eyes-on-meds,” where a team member observes and ensures that a client has taken the prescribed medications. Enhanced tasks are those that any team member can perform with appropriate cross-training from a team member with greater expertise. Specialized tasks are those that can be performed only by an expert. Care management teams usually have a mix of generic, enhanced, and specialized tasks. Although a task may be generic or enhanced, specific individuals still need to be assigned to the task. The assignment of individuals from different occupations to perform generic and enhanced tasks may strengthen a team by encouraging team members to communicate, learn from each other, and develop a team identity based on common tasks. Tasks can also be classified by their functionalities: clinical, team coordination, and team improvement. Clinical tasks are those with activities directly related to interacting with and caring for patients. Team coordination tasks are those performed to exchange information and synchronize actions among team members, such as team meetings, huddles, and setting schedules. Team improvement tasks include activities that are intended to improve task performance by measuring, monitoring, and reflecting on performance metrics and team structures and processes (Schippers, Homan, and van Knippenberg, 2013).

Table 6.2 presents a tool that can be used to determine the division of labor in a care management team. Using the nine cells in the table to guide the division of labor will ensure that:

- Specialized tasks, especially specialized clinical tasks, are assigned to team members with the appropriate expertise

- Generic tasks are rotated among team members if possible, which builds team identity by sharing tasks

- Enhanced tasks are assigned to facilitate cross-training

- Team coordination tasks are performed by team members with appropriate skills

- Team improvement tasks ideally involve the entire team

Table 6.2 Task Assignment Tool

| Functionality | ||||

| Clinical | Team Coordination | Team Improvement | ||

| Generic | ||||

| Skill level | Enhanced | |||

| Specialized | ||||

We recommend using vignettes or real situations, or both, to identify specific tasks, which will reduce the likelihood of framing the team design solely from a clinical perspective and will increase the likelihood of identifying team coordination and improvement tasks that are necessary to support clinical tasks. Describing tasks using specific terms such as “assess the housing needs for a client” rather than generic terms such as “conduct a needs assessment” is preferable because it allows the tasks to be illustrated with specific examples and ensures that what is meant to be done is clearly stated. Once the tasks have been identified and classified, the process of selecting care management team members can be addressed.

Choosing specialists is difficult because complex patients often require a wide variety of specialized skills. Criteria for choosing specialists include the importance of the skill for patient care, the importance of maintaining interdependence of the specialist with other team members, and opportunity cost. For opportunity cost, the number of patients associated with a team may not be able to support a particular specialist full time. For occupations where the opportunity cost is high, such as psychiatrists on ACT teams, primary care physicians in PCMHs, or palliative care physicians in later-life supportive care management teams, one solution is to employ a provider part time on the care management team. With this arrangement, it is important to make the part-time provider very clear about her membership and role on the team. Because certain providers may not be present full time on the team, it may be important to create a separate role for team lead. On ACT teams, for example, the team leader is a formal role often occupied by an individual with a social work background while the psychiatrist is a care management team member.

Coordination

In an extensive review of the coordination literature, Faraj and Xiao (2006, cited in Okhuysen and Bechky, 2009, p. 469) define coordination as the “temporally unfolding and contextualized process of input regulation and interaction articulation to realize a collective performance” (Faraj and Xiao, 2006, p. 1157). Okhuysen and Bechky (2009) classify coordination mechanisms in five categories:

- Plans and rules

- Objects and representations

- Roles

- Routines

- Proximity

Clearly describing the mechanisms that will be used by a care management team to coordinate care is an essential part of team design. Designing coordination mechanisms should achieve the following objectives: maximizing information sharing, minimizing process costs, and maximizing mechanism modality across different types of information. For example, electronic health records and registries are optimal for sharing codified information, whereas high levels of interdependence are needed for sharing tacit information. Specifying “boundary objects” (Nicolini et al., 2012) such as care plans or care pathways (Deneckere et al., 2012; Gittell, 2002) to support interprofessional coordination within the care management team will create a common, usable information platform that reduces ambiguity (Bechky, 2003; Gurses et al., 2008). This is true as well for specifying artifacts used in coordinating with external providers.

In implementing coordination mechanisms, one objective is implementing them in a standardized fashion (Spear and Bowen, 1999) in order to minimize errors and ambiguity (Gurses et al., 2008; Spear and Schmidhofer, 2005). In ACT, for example, team members are encouraged to record the outcome of every client encounter using the goal, intervention, result, and plan scheme, focusing on how the intervention reached its goal and developing a plan for the next encounter based on this evaluation. Another objective is implementing coordination mechanisms in a situationally aware or mindful manner (Endsley, 2000; Levinthal and Rerup, 2006). This means that coordination should flexibly adapt to a patient's emerging condition and context. For example, when ACT team members meet a client for “eyes-on-meds” and detect the presence of evidence of drug or alcohol use, this could alert the team to the reoccurrence of substance abuse. For an elderly patient, the cue could be a more disorderly living situation or unexpected symptoms. Situational awareness or mindfulness implies that team members are alert to the cues that a routine is not functioning as intended so that they can adjust the routine or reassess the care plan.

At its root, coordination is an information processing activity. Effective coordination ensures that the right individual knows the right information at the right time to perform a task effectively. For care management teams, the essence of coordination is managing like encoding, storing, and retrieving information about the patient's conditions, goals, and needs and about all the services that have been provided or are planned for the patient (Argote and Miron-Spektor, 2011; Haas, 2006).

Although the literature on coordination mechanisms is important for team design, it does not provide any tool that supports assessing the need for coordination. Table 6.3 presents a tool for assessing coordination needs by characterizing the relationship between patient information and the information acquired by the provider in terms of information availability. The need for coordination occurs only when the provider is unaware of information about the patient that he or she should reasonably know, as in the “unknown/available” cell in the table. Examples include providers not knowing a lab test result or a significant change in the patient's preference for treatment. In situations where the provider knows the patient's information and what needs to be done, as in the “known/available” cell, the patient outcome relies on the provider's performing the task at hand correctly. In situations where the provider knows that certain information about the patient is unavailable, as in the “known/unavailable” cell, an assessment is called for. An example is when a patient's care needs to shift from activities of daily living to spiritual issues as death approaches. An effective palliative care team will anticipate this shift and be watching for it. In situations where the provider does not know the patient's situation and the information is unavailable, as in the “unknown/unavailable” cell, reconsidering and reframing the patient's situation is necessary. The distinction among the cells is important because each represents a different type of cause of performance shortfalls and thus calls for a different solution. For instance, if the provider knows the patient's needs and preferences but could not do an adequate job in treating the patient, it is a task performance issue, not a coordination issue.

Table 6.3 Coordination Need Assessment Tool

| Patient Information | |||

| Available | Unavailable | ||

| Information acquired by the provider | Known | Task performance | Assessment |

| Unknown | Coordination | Reframing | |

Embedding: Care Management Team Networks

One of the defining characteristics of teams is that they “are together embedded in an encompassing organizational system, with boundaries and linkages to the broader system context and task environment” (Kozlowski and Ilgen, 2006). Care management teams are embedded in two types of networks that have to be managed to solve the care coordination problem: networks that involve relations with patients and caregivers and with other health care providers and community organizations.

Relationship with Patients and Caregivers

The relationship between care management teams and patients/caregivers can be characterized by three roles using the service provision and coordination dimension. In different contexts and with different team designs, care management teams may serve three roles in organizing care: the role of primary care provider that blends high levels of service provision and coordination, the role of specialist that focuses on service provision more than coordination, and the role of coordinator that focuses on coordination more than service provision.

In the primary care provider role, a care management team is the primary way a patient accesses health care. The care management team has a longitudinal relationship with the patient and is the first contact for a variety of health conditions (Starfield, 1992 2010; Starfield, Shi, and Macinko, 2005). As the primary care provider, the care management team helps the patient gain access to services that the team does not directly provide and coordinates such care. When we use a social network concept, the care management team in this role and the patient jointly occupy the center of the care provider network. Examples of these types of care management teams include PCMHs and ACT teams where a patient's primary contact with the health care system is through his or her partnership with the care management team.

By definition, a care team that focuses on specialty services more than care coordination does not qualify as a care management team. In certain contexts, however, a patient may need intensive specialty services, which makes the specialty team the logical locus of coordination. In this situation, the specialty team is in fact a care management team: it is responsible for providing specialty services and coordinating those services with the referring agent (often a primary care provider) and other specialists. Again, when we use a social network metaphor, a specialty team may serve as a care management team when it occupies the significant portion of the care provider network and thus shifts the center of the network from the duo of patient and primary care to that of patient and specialty care. For example, when a patient with Behçet's disease is referred to an immunology team, the team directly provides specialty services; given the patient's symptoms, the team may need to coordinate with other specialists, such as dermatologists, rheumatologists, and ophthalmologists, in treating the patient.

The role of coordinator means that a care management team focuses on coordination more than on providing services. For patients with cancer who have a strong primary care provider and oncologist relationship, for example, a palliative care team may assist these patients in linking to the other services and resources they need. The palliative care team could assist a patient with developing advanced directives and could link the patient to lawyers and spiritual advisers who could assist with legacy planning and spiritual needs, respectively. The team could support the primary care physician and oncologist in organizing later-life care for the patient. In this scenario, the care management team seeks to support, rather than supplant, the patient's existing primary care or specialist relationships.

Identifying the relationship between patients and caregivers is important in helping the care management team define its scope of practice. If the team is designed to fit its role to the patient's situation, such as taking the role of primary care provider for patients with such a provider, fidelity measures should identify or include specific processes for identifying the role the team plays in order to minimize ambiguity for both the care management team and the patient.

Relationship with Other Health Care Providers and Community Organizations

The relationship of the care management team to other health care providers and community organizations is a function of its relationship to the patient and of the institutional environment provided by the health and community system (King and Meyer, 2006). The more that the team focuses on coordination, the more that it must engage in boundary-spanning activities (Marrone, 2010) and multiteam coordination (Davison et al., 2012; Marks et al., 2005). It is likely that a fit between the institutional environment and care management team activities will influence the team's performance (Davison et al., 2012). For example, clinics that are rewarded on a pure productivity basis for the number of patients they see may have few incentives to collaborate with care management teams. In this nonsupportive contextual situation, the teams might perform poorly.

For purposes of quality improvement, monitoring the overlap of care provider networks of patients is beneficial. Monitoring these networks will identify patterns of shared patients. The larger this number is, the greater the incentive and returns are to developing coordination mechanisms among these organizations. Monitoring the care provider networks will also help the team to identify organizations that their patients most commonly see. The greater the number of shared patients between the care management team and the other organizations, the greater the incentive and returns to strengthening coordination mechanisms between them.

Implementing Care Management Teams

Care providers on care management teams apply a designed team model in specific contexts. Depending on the context, the team implementing the design, and the patients' circumstances, an identical team design may produce varying outcomes for patients and for team members. This section presents a conceptual model for care management team implementation, examining the key process factors affecting how team designs are applied to produce team outcomes. We then discuss the selected process factors that pertain to the relationships among team members, among tasks, and among team members and tasks. We focus on these factors because together they account for how care management teams can achieve care coordination through organic and interpersonal mechanisms—mechanisms that are required to coordinate under complex and uncertain circumstances and across organizational and occupational boundaries. For other factors affecting team implementation, readers should refer to other comprehensive reviews of the team literature (see Cohen and Bailey, 1997; Guzzo and Dickson, 1996; Hackman and Morris, 1975; Kozlowski and Ilgen, 2006; Lemieux-Charles and McGuire, 2006; Mathieu et al., 2008).

A Conceptual Model

Figure 6.2 shows the conceptual model for care management team implementation. It builds on current research on care coordination and team effectiveness. Research on system improvement indicates that three key principles for designing high-performance teams are clearly specified tasks and roles, unambiguous communication, and simple and direct work flows (Ghosh and Sobek, 2006; Gurses et al., 2008; Spear and Bowen, 1999). Research on team effectiveness reveals that the relationship between team design and team outcomes is moderated (Kenny, 2011b) and mediated (Kenny, 2011a) by team processes and emergent states (Cohen and Bailey, 1997; Ilgen et al., 2005; Kozlowski and Ilgen, 2006). Team processes are interactions among team members, while emergent states describe cognitive, motivational, and affective states of teams (Marks, Mathieu, and Zaccaro, 2001). We see care coordination as a dynamic, emergent, and adaptive process operating in specific clinical contexts (Allred, Burns, and Phillips, 2005; Lemieux-Charles and McGuire, 2006) with the relationship between team design and team effectiveness (i.e., achieving desired patient and staff outcomes) being moderated and mediated by team processes. Consistent with research showing that well-designed teams perform better than poorly designed teams (Cohen and Bailey, 1997) and that leadership and quality improvement activities work better in well-designed teams (Wageman, 2001), research on ACT teams shows that fidelity to team design can improve client outcomes, but important variation exists across teams and contexts (Burns et al., 2007). Such variation can be attributed to team processes occurring during team implementation. Leadership, for example, facilitates team learning to identify problems of wasted effort; develop, implement, and test interventions to fix the problems; and adopt effective interventions. Leadership similarly facilitates the implementation of evidence-based practices (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2013).

Figure 6.2 A Conceptual Framework for Care Management Team Implementation

For care management teams, we list the key moderating and mediating team processes in figure 6.2 and discuss their roles in translating team design into team outcomes (Kenny, 2011a 2011b). First, research suggests that a constructive context moderates the relationship between team design and team performance by promoting growth, development, and the performance capabilities of team members (Wholey et al., 2013). A constructive context is a safe environment where information and ideas can be freely exchanged and task processes refined and includes team processes such as team learning—training and quality improvement activities (Levitt and March, 1988; Tucker, Nembhard, and Edmondson, 2007); constructive controversy—team processes with which team members express their opinions directly and explore opposing positions open-mindedly when resolving conflicts (Shah, Dirks, and Chervany, 2006); and (lack of) conflict—perceived incompatibilities, opposing interests, or discrepant views among team members (Jehn, 1995). The constructive context also includes emergent states such as psychological safety (a shared perception that the team is a safe place for admitting errors, asking for assistance, or discussing difficult issues without the fear of negative consequences to individuals; Edmondson, 1999), and goal agreement (a shared perception of a team's priorities and objectives; Zohar, 2000). A constructive context is likely to be particularly important for teams focusing on information management, such as care management teams. It is worth noting that while the moderating processes and states appearing in figure 6.2 are distinctive constructs, they are interrelated. Psychological safety, for example, is a moderating state for care management teams because it improves the implementation of evidenced-based practices (Tucker, Nembhard, and Edmondson, 2007), and it is likely associated with constructive controversy.

Second, interpersonal processes such as team members helping each other to perform tasks and states such as transactive memory and social capital—knowing who has what expertise and knowing who would help if requested—moderate the relationship between team design and team performance by cultivating a highly interdependent work system and facilitating information sharing. A key function of care management teams is information management. Not only do care management teams need to assess and manage information about patients' circumstances, they also need to monitor and coordinate services provided by providers outside the team. Because less expensive coordination mechanisms are available for patients with less complex conditions, care management teams usually focus on patients with greater complexity and uncertainty. For complex, dynamic, evolving, and emergent patient circumstances, information management requires a significant amount of patient-specific knowledge that has to be interpreted and integrated by multiple professionals. Teams can invoke two types of information management and coordination mechanisms. First, rules, protocols, standardized roles, and information media (traditional media like paper forms, or electronic ones such as electronic health records) can be used to coordinate actions for routine issues and manage codified information (Okhuysen and Bechky, 2009). Second, more organic mechanisms and a highly interdependent work system are required to coordinate actions and manage information for complex and uncertain circumstances. In this situation, a large amount of information, often tacit or not codifiable, has to be gathered during task performance to complete the task effectively (Galbraith, 1974).

Interpersonal processes and states can be characterized and studied from a social network perspective. Social networks within care management teams are a key determinant of information management and performance (Balkundi and Harrison, 2006; Flap, Bulder, and Völker, 1998). High levels of interdependence, for example, facilitate the exchange of tacit information and promote cohesion and helping behavior among team members (Lawler, Thye, and Yoon, 2009). Explaining the role of social networks in care management teams promises significant improvement in our understanding of the variation in outcomes across superficially similar teams. Even in teams of ten to twelve individuals, organizational processes are likely to create subteams (Simon, 1962; Thompson, 1967), hierarchy, and peripheral actors. These varying relational structures affect teams' cohesion, effectiveness in information management, and performance. Incorporating social networks in team research and implementation is important because social networks are manageable. Team leaders can change networks relatively simply by managerial actions, such as by assigning different individuals to work together or through arranging new interaction opportunities.

Third, the mediating team processes and states in care management team implementation include information accessibility, encounter preparedness, and patient-centered care. In care management teams, team design, constructive context, and interpersonal processes all contribute to ensure that the right information is available to the right individual at the right time. Information accessibility characterizes the process by which team members acquire task-relevant information efficiently, with minimal waste (Spear and Bowen, 1999; Shah and Ward, 2007). The consequence of having information available is that team members can be more attentive to or improve situational awareness of patients' circumstances (Endsley, 2000). Situational awareness has two components: encounter preparedness and patient-centered care. Encounter preparedness entails being sufficiently prepared for patient encounters by having knowledge of a patient's current conditions, needs, and goals and knowing the schedule and specific tasks. Patient-centered care entails observing elements of an encounter that requires adapting care to a patient's diagnosis, needs, and goals. Encounter preparedness is a necessary condition for patient-centered care because it enables care management team members to recognize when and how an encounter differs from expectations and to adapt responses to the emergent situations. We anticipate that encounter preparedness will reduce team member stress because it clarifies the situation and expectations and will improve patient-centered care by making departures from plans that result in more appropriate adjustments. Patient-centered care will ultimately improve patient outcomes. Encounter preparedness and patient-centered care are reasonable end points for the analysis of care management team implementation because the linkage between patient-centered care and patients' medical or social outcomes is likely to be attenuated by a wide variety of exogenous factors.

Relational Aspects of Team Implementation

This section provides some hypotheses for relational aspects of care management teams based on the emergent states that affect their functioning. These states reflect four types of relationships:

- The effect of interdependence on team climate and encounter preparedness, having the necessary information for providing effective patient care at patient encounters

- Social capital, that is, being able to turn to other team members for help

- Transactive memory, that is, knowing the knowledge, skills, and abilities of other team members

- The effect of interdependence and sharing common tasks on the development of team identity, based on the argument that individuals from differing occupations performing generic tasks facilitate the adoption of a team identity while specialists performing specialized task facilitate professional identification

Interdependence and Standard Work

Social networks, particularly work interdependence within care management teams, are likely to play an important role in creating an environment with desirable team processes (e.g., constructive controversy and psychological safety), which influences the team's ability to perform its tasks. While there are many types of network ties among care management team members, we focus on work relationships because they are critical in these teams. Care management teams consist of highly interdependent professionals with complementary skills. Their success is contingent on members' abilities to integrate their activities. Work interdependence characterizes how closely team members work with one another. Interdependence is likely to affect constructive controversy and psychological safety, which in turn affect encounter preparedness.

Constructive controversy is the critical and open discussion of divergent perspectives, including task-related facts, data, and opposing ideas, using a respectful tone (Tjosvold, 1985). Conflict of this nature is a critical component to group performance (Jehn and Shah, 1997; Shah and Jehn, 1993). Research findings point to differences in both how conflict is manifested and the norms for managing conflict in groups based on preexisting relationships (Jehn and Shah, 1997; Shah et al., 2006; Shah and Jehn, 1993). Specifically, researchers investigating friendship find that friends deal with conflict more effectively and have a greater focus on conflict resolution than nonfriends do (Aboud, 1989; Gottman and Parkhurst, 1980; Nelson and Aboud, 1985). While much of the previous work on conflict in teams focused on friendship, network researchers find a strong overlap between affective and work tie networks (Shah, 1998 2000). Thus, we hypothesize:

- Hypothesis: Interdependence will positively influence constructive controversy in care management teams.

Psychological safety describes a supportive environment where employees can take interpersonal risks such as admitting mistakes, asking for assistance, exposing the mistakes of others, or making controversial suggestions without fear of negative consequences to their self-images, statuses, or careers (Edmondson, 1999). It is also related to team performance by resulting in greater team learning, job involvement, work effort, and smoother problem solving (Edmondson, 1999). When teams engage in constructive controversy, a respectful tone is used to discuss differences of opinion, which may foster psychological safety. Thus, we hypothesize:

- Hypothesis: Constructive controversy will positively influence psychological safety.

Psychological safety creates a collaborative work environment where individuals freely share ideas and information. Information sharing is critical in care management teams. Easy information access ensures that team members will be prepared for client encounters. Thus, we hypothesize:

- Hypothesis: Psychological safety will positively influence ease of access to information, which in turn will lead to greater encounter preparedness.

Social Capital

Social capital derives from social network perspectives developed by sociologists (Burt, 1992; Coleman, 1988; Lin, 2001) that emphasize an individual's access to important resources controlled by others to whom they are connected. Our conceptualization of social capital is based on a theoretical refinement of the concept by Johnson and Knoke (2004), which states that social capital is also contingent upon team members making those resources available to the individual.

Teams with greater fidelity to care management team design standards likely have greater team social capital. The greater the interdependence among care management team members, the more social capital the team has. Because team social capital provides access to information about patients and tasks, higher levels of social capital should be associated with greater encounter preparedness:

- Hypothesis: Social capital will positively influence ease of access to information, which will lead to greater encounter preparedness.

Transactive Memory System

A transactive memory system (TMS) is a collective cognitive mechanism for encoding, storing, and retrieving knowledge and information in teams. Such a system is likely to develop in care management teams when team members closely interact with one another and collaborate on task performance. Over time, team members develop a shared cognition of who knows what and a division of cognitive labor that they depend on one another for specialized knowledge and information in different task areas. Research shows that transactive memory has a positive effect on team performance. Teams that have developed such a cognitive mechanism can coordinate team members more effectively, possess deeper knowledge in each specialized area, and perform better (Liang, Moreland, and Argote, 1995; Moreland and Myaskovsky, 2000). Research also shows that transactive memory facilitates team learning and knowledge transfer (Lewis, Lange, and Gillis, 2005). Given the interprofessional nature of care management teams, transactive memory is a crucial team cognitive state that underpins their effective implementation.

We expect care management teams with better-developed transactive memory systems to have better patient outcomes. We also expect transactive memory will improve a care management team's ability to adopt new EBPs. Teams that have a clear specialization structure are particularly likely to absorb new knowledge and cope with the complexity of implementing new EBPs more effectively. Previous research suggests that group training, work interdependence, and team stability have positive impacts on transactive memory, and turnover and acute stress (as a result of a sudden disruptive event) have negative impacts (Akgün et al., 2005; Ellis, 2006; Lewis et al., 2007; Liang et al., 1995):

- Hypothesis: TMS will positively influence ease of access to information, which will lead to greater encounter preparedness.

Identity

While social networks, interdependence, and transactive memory help to define care management teams and how they perform tasks, identity processes help to maintain the expanded social order within which these teams are embedded.

Identity refers to perceptions of who or what one is, which is based on the set of meanings individuals attach to themselves and others and on the reflexive interpretation of others' behavior toward them as providing meaning to their identity (Gecas and Burke, 1995). In interacting with others, identities define self-other classifications such as that of an individual's role of parent, caregiver, husband, or teacher. Identities also arise as self-group or social category such as that of one's gender, race, professional society member, Chicago Tribune employee, palliative care team member, or University of North Carolina alumnus. These identity processes provide norms for behavior that are local in nature but also grounded in the larger social structure and cultural beliefs (Lawler, Thye, and Yoon, 2009).

Identity theory is grounded in structural symbolic interactionism (SSI; Stryker, 1980) and traditional symbolic interactionism (TSI; Blumer, 1969), which both emphasize understanding human social behavior “by focusing on individuals' definitions and interpretations of themselves, others, and their situation” (Burke and Stets, 2009, p. 33). According to SSI, individuals ascribe meaning to their positions within the social structure, and the roles they assume shape how they perceive themselves and how they behave. TSI places less emphasis on social structure in examining human behavior, seeing structure as temporary social order in which participants, having interpreted and defined meaning and actions, actively assemble and disassemble social structure (Burke and Stets, 2009). This latter view simplifies identity to mere categorization and comparison with references, promoting shared group social identities through which arise expectations for behavior, including understanding the in-group versus the out-group (Lawler et al., 2009).

Teams in health care, whether care provider teams, clinics, care management teams, or other types, involve repeated interactions of members in interdependent tasks and actions. Over time these interactions strengthen the commitments within person-group ties through identity processes. These group identities shape the way people interact and how they treat one another, even if they lack interpersonal ties (Lawler et al., 2009):

- Hypothesis: Interdependence will produce higher levels of identity, which will be associated with higher levels of helping others.

Conclusion

We have described care management teams in detail, contrasting them to both care provider teams and clinics. We then presented a theoretical model for care management teams—a CMOc model—and methods for developing fidelity standards for care management teams, followed by examples demonstrating applications for studying care management team performance. We argue that care management teams are the preferred way to assess what is and is not a “team”; are the most useful way to organize care, especially chronic and primary care; and are genuinely patient centered and able to provide a spectrum of comprehensive and integrated care. Our theoretical model of care management teams treats these teams as causal entities leading to various outcomes contingent on their context, and we suggest that their CMOc enhances the implementation of care management teams.

We close this chapter by suggesting the high relevance of network theory or analysis (as outlined in chapter 10, this volume) to our discussion of teams and team design. A key conceptual idea is the ego network, defined as all the direct contacts between a particular node or person (patient) and other nodes or persons (providers). Understanding the network structure of each patient's ego network that is the basis of a care team is likely to pay large dividends, in part because it helps avoid wasting effort on inappropriate solutions to the care coordination problem. Arguments that focus on developing interorganizational linkages to solve the care coordination problem, for example, implicitly assume that care team ego networks overlap strongly enough to justify the expense of investing in interorganizational coordination mechanisms among clinics. While research examining the overlap in the network structure across care teams is needed to directly address this issue, these team networks will probably be quite dissimilar across patients with severe and complex conditions. In palliative and end-of-life care, for example, the care team is likely to consist of a patient's family members, other caregivers, and a diversity of health care providers who have accumulated over time. In ACT, each client's mental illness has likely generated substantially different ego networks across patients. Given the complexity of each individual's conditions, few patients will share the same care team and have the same organizations in their ego network. The implication is that before investing in solutions such as interorganizational coordination mechanisms, it may be useful to determine whether such solutions will actually be beneficial. Care management teams are more likely a solution to the care coordination problem because they can be customized in a patient-centered manner.

Similarly, the network structure in care management teams might affect their functioning in a number of ways. Interdependence within the team, the network structure of working closely together, could affect coordination, trust, cohesion, transactive memory systems, social capital, and identity among team members. Team leaders can manage interdependence by using policies to assign people to tasks and integrate tasks through developing care pathways, which are networks of tasks. In sum, understanding the ego networks associated with care teams and the work and helping networks involved can potentially pay large dividends in moving teams beyond fidelity—the implementation of care programs faithful to a clear conceptual interventional framework—to structures and processes for achieving the next level of performance.

Key Terms

- Care management teams

- Care provider teams

- Clinics

- Constructive controversy

- Context-mechanism-outcome configuration

- Fidelity

- Interdependence

- Patient-centered care

- Psychological safety

- Social capital

- Social networks

- Team identity

- Transactive memory