Long-term debt includes any financial obligations lasting more than 1 year. The two most common items are bonds, which are covered in this chapter, and leases, which are covered in Accounting for Fun and Profit: Understanding Advanced Topics in Accounting.

A bond represents a contract between two parties: the borrower (issuer) and the lender (purchaser). This chapter takes the perspective of the firm issuing the bond (i.e., borrowing the money), which makes the bond a liability on the Balance Sheet (increase cash and debt). A mirror image of the discussion applies if the firm purchases another firm’s bonds (and the bond would be an asset).

Corporate bonds are typically payable over long periods of time, normally ranging from 3 to 30 years.1 There have also been bonds with much longer lives. In 1993, the Walt Disney Company issued $300 million of bonds with 100-year lives (the firm had the right to buy back the bonds after 30 years). Wall Street promptly called them “Sleeping Beauty Bonds.”2

The terms of a bond, the amounts to be paid and the payment dates as well as any special features, are stated in a legal document called the bond indenture. The key to understanding bonds is to understand all the terms related to them as well as the concept of the time value of money discussed in Chapter 8.

Face value, par value, or maturity value. All three terms mean the same thing. This is the final payment at the end of a bond’s life, which means when the bond obligation is terminated.

The coupon rate, contract rate, or stated rate. All three terms mean the same thing. This is the interest paid as calculated by taking a percentage of the bond’s face value each year. The coupon is the actual interest payment.3 In the United States, interest on bonds is normally paid twice a year, whereas in Europe, interest on bonds is normally paid once a year (so in the United States, the actual coupon payment is one-half of the coupon rate, because coupon rates are listed in the terms as an annual rate). The actual payment, the amount and when it is paid, is contractually stated in the terms of the bond.

The price or market value. This is the value assigned to the bond at the present time by investors. It represents the present value (PV) of all future payments in the bond contract, discounted at what investors (the market) consider the appropriate discount rate (different from the coupon rate explained above). If the bond is issued at its face value (which is often the case today), the bond is said to be sold at par. If the bond is issued at a price above face value, the bond is said to be sold at a premium. If the bond is issued at a price less than its face value, it is said to be sold at a discount. Bond valuation is discussed in Chapter 8.

The yield (to maturity), effective rate, or market rate. All three terms mean the same thing. This is the discount rate mentioned above, which equates the price of the bond with all future payments (coupons and face value). Note that the coupon rate (or coupon) does not change over the life of the bond: It is a contractual rate set in the bond indenture. By contrast, the discount rate (i.e., yield, effective rate, or market rate) changes because of changes in the economy (e.g., as government interest rates rise or fall, so will the firm’s discount rate) as well as changes in the market’s perception of the firm’s risk level (e.g., the likelihood that all of the payments related to the bond will be made). As the discount rate changes, so will the price of the bond (as explained in the bond valuation section in Chapter 8).

Covenants are restrictions placed on the issuer/borrower that, if violated, allow the bondholder to demand immediate repayment of the bond. They can be set as actions the borrower is not allowed to undertake (e.g., paying dividends above a certain amount of earnings, limiting additional debt, prohibiting senior debt), actions the borrower must take (e.g., providing annual audited statements to the bondholders or their agent), or creating some prescribed standard the borrower must meet (e.g., maintaining a set ratio such as current assets to current liabilities of 1.5 or more).4

Security or collateral represents specific assets pledged to the bonds if the company cannot repay its obligation.5 That is, if a firm does not meet any of the terms of the bond (e.g., fails to make a coupon payment or violates a covenant), the bondholder can demand immediate payment of the bond’s face value. If the firm is unable to pay (which is likely if the firm missed a coupon payment), the bondholder can take possession of the security and sell it to obtain repayment. If the funds from the sale are greater than the amount owed, the balance is returned to the firm. If the funds from the sale are less than the amount owed, the bondholder has an unsecured claim (along with all other unsecured claimants) on all of the firm’s other assets. Note that bonds can be secured or unsecured. Bonds that are unsecured are also called debentures.6

Priority of claims or payments. Whether secured or unsecured, bonds can specify a priority of payment in the event of liquidation or bankruptcy. Senior debt (first priority) is paid before junior debt (second priority). Priority exists by default between secured and unsecured bonds, because secured bonds have collateral that is handed over to bondholders. But priority can be explicitly laid out within secured and unsecured bonds as well (e.g., senior and junior secured, senior and junior unsecured).

Redeemable bonds contain a feature that provides the bondholder the option to exchange the bond for a preset value (often at a slight discount to the face value) prior to the final maturity of the bond. A single bond can have multiple dates at which bondholders are able to exchange their bonds and can have different values for each date. However, most bonds are nonredeemable.

Callable bonds contain a feature that provides the issuer the option to pay off the debt at a preset price (often at a slight premium over the face value) prior to the final maturity of the bond. As noted above, Disney’s 100-year “Sleeping Beauty” bonds have a 30-year call feature. Disney reserved the right to buy back the bonds (i.e., force the bondholders to sell them back to Disney) after 30 years.

Convertible bonds contain a feature that allows the bondholder to exchange the bond into shares of the firm’s equity at a set rate(s) on a specific date(s). For example, let us say a bond with a face value of $1,000 is exchangeable into 50 shares of common stock on July 1, 2018. Let us also say the market price of the 50 shares on July 1, 2018, is above the price of the bond (remember, the price of the bond is the PV of the future coupon payments and face value). The bondholder has an incentive to swap his convertible bond for the shares. There are numerous variants of this theme (i.e., the bonds can have a call feature where the firm can force the bondholders to convert to equity at a specific date). The conversion features allow the bondholder to gain if the firm’s stock price rises dramatically. In return for this option, the bond has a lower coupon rate. This can be attractive for high-risk firms, as they would otherwise have to offer high coupon rates. The majority of bonds issued are nonconvertible.

Bond Ratings

There are companies that provide their opinions on the likelihood that a firm’s debt will be repaid. These opinions are given in the form of a rating or score. In the United States, there are three major firms that do this. Standard and Poor’s (S&P) and Moody’s dominate the market, followed by Fitch Ratings (Fitch). Each firm has a slightly different rating system. For example, S&P (and Fitch) has its best rating as AAA followed by AA+, AA, AA−, A+, and so on. By contrast, Moody’s top rating is Aaa, followed by Aa1, Aa2, Aa3, A1, and so on. Exhibit 9.1 provides a description of various ratings for S&P. It is important to note that the issuing firm pays the rating agencies, which only issue an opinion (like the audit report) but, by government fiat, cannot be sued for issuing incorrect or misleading opinions (unlike the auditors). As such, and because rating agencies have proven unreliable in the past, your author suggests they are of dubious value to investors.7 The ratings become important because various financial institutions (e.g., banks, insurance companies, and pension plans) are required by law to hold only securities rated BBB (called “investment grade”) and above. Thus, the government has created a market for these ratings.

Accounting for Bonds

The accounting for bonds at the time of issue is straightforward. (Remember that we are looking at bonds from the issuer’s perspective.) The issuing firm receives cash and has a long-term liability (increase cash and debt). Over time, the firm records interest expense at the time of payment (and if payment is not at year-end then, at year-end, an adjustment is made for the partial period from the last payment to year-end). If the bond is paid off at the end of its life, the final payment reduces the debt to zero. If the bond is paid off prior to its maturity date, then a gain or loss is recorded if the payment is more (loss) or less (gain) than the outstanding debt.

To illustrate, assume a 3-year bond with a 6 percent semiannual coupon is issued at par on January 1, 2015. The accounting entries for the bond would be as follows:

Using entries:

The last three entries are repeated in 2016 and 2017, with one final entry at the end of the bond’s 3-year life:

What if the bond is repurchased prior to its maturity date at a value different from its accounting (book) value? There will be a gain or loss on the repurchase. For example: What is the accounting entry if the bond was purchased on January 1, 2017, for $1,009,637?8 It is:

The bond payable is reduced to zero, cash is reduced by the amount the issuer paid to repurchase the bond, and there is a loss on the repurchase because the price paid is above the bond’s accounting value. Had the bond been purchased for $990,502,9 the firm would have recorded a gain of $9,498. Note that the gain or loss is determined by the difference in the market value of the bond and the bond’s accounting value at the time: The price the issuer paid to repurchase the bond minus value of bond on the books equals the gain or loss to be recorded.

Finally, to illustrate a bond payment made on a date other than year-end, assume the above bond was issued on February 1, 2015, with interest payments on July 31 and January 31 and a final maturity on January 31, 2018. The entries would be as follows:

As can be seen, when financial statements are prepared at the end of the year, $25,000 in interest is accrued for the 5 months from the prior payment on July 1. Then, when the $30,000 coupon payment is made on January 31, the payment amount reduces the $25,000 liability from the prior year and $5,000 of interest for the 1 month is recorded. For the payment on July 1, the full amount is recorded as a decrease in cash and an increase in interest expense. Then at year-end, the $25,000 accrual is made again.

Other Types of Bonds

The above description is for a regular, or ordinary, type of bond that has periodic interest payments and a lump sum payment at the end of its life. However, there are numerous other types of bonds (indeed almost any payment stream can be written into the indenture).

Let us consider a much simpler bond: a zero-coupon bond. This is a bond that makes no periodic interest payments (it has a coupon with a zero interest rate). All of the compounded interest is reflected in the final payment. Thus, the bond’s price must be lower than its face value (the final payment) because the final payment includes all of the interest earned. Staying close to our example above, assume a 3-year bond issued for $1 million on January 1, 2015, yielding 6 percent compounded semiannually but making no payments until it matures on December 31, 2017, for $1,194,052.10

Despite no cash being paid, the interest expense is still recorded and the bond payable increases over time until it is repaid in one lump sum. Also, note that retained earnings are changing at the end of the calendar year (December 31 of 2015 and 2016) because the firm closes its books and prepares its Income Statement at the end of each calendar year.

The accounting entries would be as follows:

A serial bond, or mortgage bond (or mortgage), is normally given with real estate as collateral and often has only periodic payments with no final lump sum (i.e., it is basically an annuity, which was described in Chapter 8). Staying close to our example above, assume a 3-year bond making payments twice a year (on June 30 and December 31) is issued for $1 million on January 1, 2015, yielding 6 percent compounded (paid) semiannually. What are the periodic interest payments? They are $184,598.11 The accounting for the bond would be as follows:

As shown in the amortization table that follows, each cash payment of $184,598 is part interest and part bond repayment. The interest portion is reduced over time from $30,000 ($1 million × 3%) to $5,377 ($179,218 × 3%) because the balance owed is declining. As the interest portion falls, the bond repayment portion (a decrease in debt, or accumulated bond repayment) increases from $154,598 ($184,598 − $30,000) to $179,219 ($184,598 − $5,379) because the amount that has been cumulatively paid increases with each payment.

Let us compare across the three different types of bonds. In the regular bond example, the interest expense stayed the same over time because the amount of debt borrowed stayed constant (as the interest was always being fully paid). In the zero-coupon bond example, the interest expense increased over time as the debt increased with the compounded interest. In the mortgage bond example, the interest expense falls over time because the debt is being reduced (at increasing amounts) with each payment.

Differences in interest expense across the three types of bonds:12

If, at the date of issue, the market rate (or yield) on a bond is less than its coupon rate, then the bond will be issued at a price above par value (called a premium). If, at the date of issue, the market rate (or yield) on a bond is more than its coupon rate, then the bond will be issued at a price below par value (called a discount).

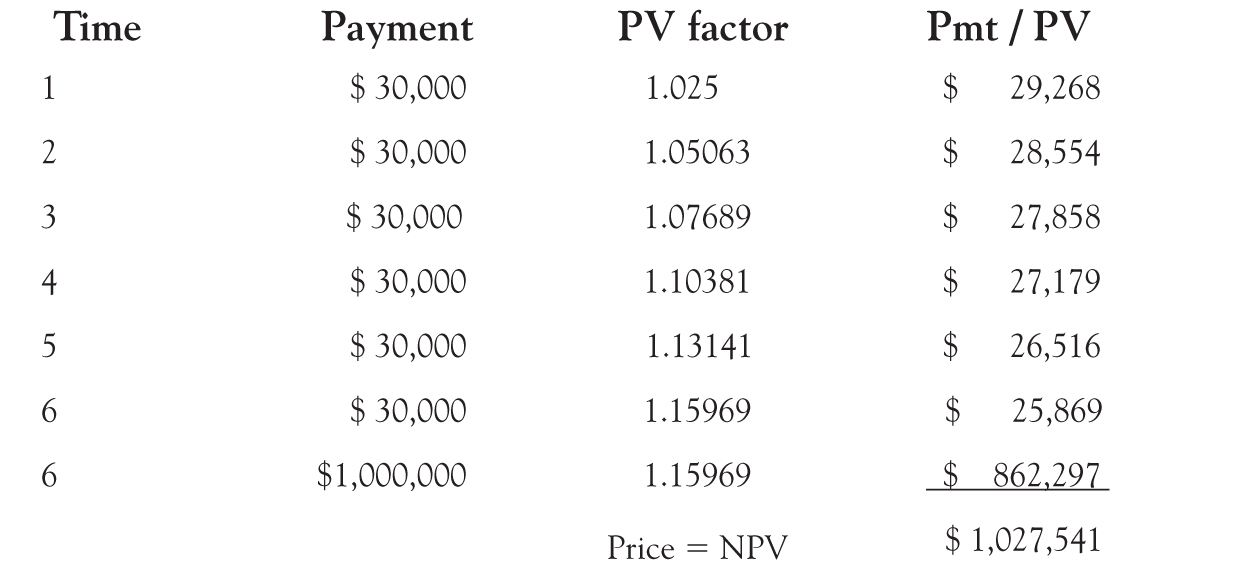

To illustrate, assume a 3-year bond with a face value of $1 million and a 6 percent semiannual coupon (or $30,000 every 6 months) is issued on January 1, 2015, with a yield of 5 percent compounded semiannually.13 Because the coupon of 3 percent (6 percent semiannual coupon divided by two) is more than the yield of 2.5 percent (the 5% / 2), the bond will be sold at a price above its face value (more than $1 million). Remember that the bond’s price equals the PV of all the coupon and face value payments. This means the price can be computed like any other PV computation:

Using a spreadsheet:

The accounting entry for the bond at the date of issue could be simply:

However, normally the accounting sets up the bond payable liability at the face value, which means a separate account is set up for the premium or discount (the latter being a contra account similar to allowance for doubtful accounts). Thus, the entry for the above example would be as follows:

Note that on the Balance Sheet, the liabilities would be the net bond payable (the bond payable plus the premium or less the discount).

The discount or premium is then amortized (reduced to zero) over the life of the bond. Many years ago, prior to personal computers, it was common to amortize using a “straight-line method” by dividing the discount or premium by the number of payments (in this case, it would have been the $27,541 premium divided by the six payments in the 3-year life of the bond = $4,590). Interest expense would have been the cash payment less the straight-line amortization amount in the case of a premium, or the cash payment plus the straight-line amount in the case of a discount. Thus, the periodic entry for each interest payment would have been as follows:

The interest expense would have been calculated as $25,410 ($30,000 − ($27,541 / 6)), and the amount would be the same each time an interest payment (cash down) were made and prompted an interest expense to be recorded.

Today the premium or discount must be amortized using what is called the “effective rate method.” Here, the yield at the date of issue is applied on the net Balance Sheet amount (which means bond payable less the discount or plus the premium) to obtain the interest expense. Then the difference between the interest expense and cash is the amortization on the discount or premium. Following today’s practices, the first entry in our example would be as follows:

The interest expense will thus decrease over time with a premium or increase over time with a discount. As the premium (discount) is reduced to zero, the interest expense declines (increases) because the rate times the face value plus (minus) the declining premium (declining discount). The amortization table that follows shows how the amounts change for the example:

Note that, in the example, the interest expense is always 2.5 percent times the net amount owed. After the final payment, the discount or premium on the bond has been reduced to zero. On the last day, the face value ($1 million) is paid and the debt is removed.

When long-term debt matures in the coming year, the amount is reclassified to current liabilities under the caption “current portion of long-term debt.” However, normally the entire amount is still also shown as long term, less the current portion, for a net amount.

The Bottom Line

This chapter covered the terminology and accounting for long-term debt. The next chapter completes our walk down the Balance Sheet by looking at owners’ equity.

_________________

1US government bonds have durations from 90 days (for a U.S. Treasury bill), to 10 years (for a U.S. Treasury note), to 30 years (for a U.S. Treasury bond).

2Other organizations issuing 100-year bonds such as Coca-Cola, Federal Express, Ford Motor, and several universities, including Tufts University and MIT. There have also been 1,000-year bonds issued, and the UK government issued bonds with no maturity date called Consuls, which basically make interest payments forever (and are thus called perpetuals). Almost anything can be included into a bond contract. For example, the All England Tennis Club, where the Grand Slam Wimbledon tennis matches are played, has issued bonds which give the bondholders tickets to Wimbledon tennis matches.

3Many years ago, bonds had detachable coupons: Parts of the bond would be literally cut from the actual hard copy of the bond, with an amount and a date written on it. The coupon would be submitted to the issuing firm on or after the date on the coupon, and the firm would then pay the amount of the coupon. Modern bonds no longer have coupons that literally detach and funds are nowadays normally transferred electronically to the registered owner of the bond; however, the term “detachable coupon” or “coupon” remains to describe the periodic interest payments.

4Almost anything can be written into the bond contract. For example, bonds may contain a provision saying that the bondholder can demand repayment if there is a hostile, or any, takeover of the firm. If a bond has few or no covenants it is referred to as “covenant light.”

5The security or collateral does not have to be a physical asset. In 1997, the singer David Bowie issued $55 million of 10-year bonds where the collateral was the royalties from certain songs of his. The bonds were dubbed Bowie Bonds by Wall Street.

6Although the term debenture means an unsecured bond, whether the bond actually has security or not depends on the indenture. Your author has seen “secured debentures,” which indicates the lawyer drafting the indenture wanted to use a more grandiose term than bond and apparently did not know that the word debenture means unsecured bond.

7Prior to the financial crisis of 2009, these agencies were rating numerous securities as AAA, which proved to be next to worthless (in fact, at the time, even without hindsight, any reasonable examination should have led to ratings well below BBB).

8As explained in Chapter 8, this would be the bond price if the yield fell to 5 percent compounded semiannually ($30,000 / 1.025 + $1,030,000 / 1.0252).

9This would be the bond price if the yield increased to 7 percent compounded semiannually ($30,000 / 1.035 + $1,030,000 / 1.0352).

10As explained in Chapter 8, this is simply $1 million × 1.036 = $1,194,052. Also, note that coupon payments do not compound (do not pay interest on interest). The coupon is a payment that would have to be reinvested. By contrast, the interest on a zero-coupon bond does compound as it is not paid until the end of the bond’s life.

11As explained in Chapter 8, it would be $1,000,000 / (1/1.03 + 1/1.032 + . . . +1/1.036).

12Remember, the interest expense and the payment do not have to be the same.

13The 5 percent semiannual yield is on the issue date and will change over time.