Chapter 4

Reporting Profit

In This Chapter

![]() Taking a look at typical income statements

Taking a look at typical income statements

![]() Getting inquisitive about the substance of profit

Getting inquisitive about the substance of profit

![]() Becoming more intimate with assets and liabilities

Becoming more intimate with assets and liabilities

![]() Handling unusual gains and losses in the income statement

Handling unusual gains and losses in the income statement

![]() Correcting misconceptions about profit

Correcting misconceptions about profit

In this chapter, I lift up the hood and explain how the profit engine runs. Making a profit is the main financial goal of a business. (Not-for-profit organizations and government entities don’t aim to make profit, but they should break even and avoid a deficit.) Accountants are the profit scorekeepers in the business world and are tasked with measuring the most important financial number of a business. I should warn you right here that measuring profit is a challenge. Determining the correct amounts for revenue and expenses to record is no walk in the park.

Managers have the demanding tasks of making sales and controlling expenses, and accountants have the tough job of measuring revenue and expenses and preparing financial reports that summarize the profit-making activities. Also, accountants are called on to help business managers analyze profit for decision-making, which I explain in Chapter 9. And accountants prepare profit budgets for managers, which I cover in Chapter 10.

This chapter explains how profit activities are reported in a business’s financial reports to its owners and lenders. Revenue and expenses change the financial condition of the business, a fact often overlooked when reading a profit report. I explain these asset and liability changes in the chapter. Business managers, creditors, and owners should understand the vital connections between revenue and expenses and their corresponding assets and liabilities. Recording revenue and expenses (as well as gains and losses) is governed by established accounting standards, which I discuss in Chapter 2. The accountant should follow the standards, of course, but there is a lot of wiggle room for interpretation.

Presenting Typical Income Statements

At the risk of oversimplification, I would say that businesses make profit three basic ways:

![]() Selling products (with allied services) and controlling the cost of the products sold and other operating costs

Selling products (with allied services) and controlling the cost of the products sold and other operating costs

![]() Selling services and controlling the cost of providing the services and other operating costs

Selling services and controlling the cost of providing the services and other operating costs

![]() Investing in assets that generate investment income and market value gains and controlling operating costs

Investing in assets that generate investment income and market value gains and controlling operating costs

Obviously, this list isn’t exhaustive, but it captures a large swath of business activity. In this chapter, I concentrate on the first and second ways of making profit: selling products and selling services. Products range from automobiles to computers to food to clothes to jewelry. Services range from transportation to entertainment to consulting. The customers of a business may be the final consumers in the economic chain, or a business may sell to other businesses.

Looking at a product business

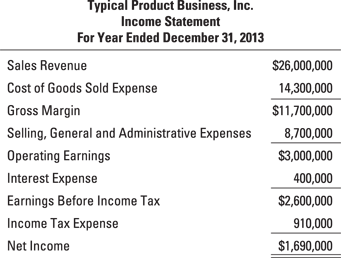

Figure 4-1 presents a typical profit report for a product-oriented business; this report, called the income statement, would be sent to its outside owners and lenders. The report could just as easily be called the net income statement because the bottom-line profit term preferred by accountants is net income, but the word net is dropped off the title and it’s most often called the income statement. Alternative titles for the external profit report include earnings statement, operating statement, statement of operating results, and statement of earnings. (Note: Profit reports distributed to managers inside a business are usually called P&L [profit and loss] statements, but this moniker is not used in external financial reporting.)

The heading of an income statement identifies the business (which in this example is incorporated — thus the term “Inc.” following the name), the financial statement title (“Income Statement”), and the time period summarized by the statement (“Year Ended December 31, 2013”). I explain the legal organization structures of businesses in Chapter 8.

You may be tempted to start reading an income statement at the bottom line. But this financial report is designed for you to read from the top line (sales revenue) and proceed down to the last — the bottom line (net income). Each step down the ladder in an income statement involves the deduction of an expense. In Figure 4-1, four expenses are deducted from the sales revenue amount, and four profit lines are given: gross margin; operating earnings; earnings before income tax; and, finally, net income.

Figure 4-1: Typical income statement for a business that sells products.

Looking at a service business

You find many variations in the reporting of expenses. A business — whether a product or service company — has fairly wide latitude regarding the number of expense lines to disclose in its external income statement. Accounting standards do not dictate that particular expenses must be disclosed. Public companies must disclose certain expenses in their publicly available fillings with the federal Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Filing reports to the SEC is one thing; in their reports to shareholders, most businesses are relatively stingy regarding how many expenses are revealed in their income statements.

Figure 4-2: Typical income statement for a business that sells services.

Taking care of some housekeeping details

![]() Minus signs are missing. Expenses are deductions from sales revenue, but hardly ever do you see minus signs in front of expense amounts to indicate that they are deductions. Forget about minus signs in income statements, and in other financial statements as well. Sometimes parentheses are put around a deduction to signal that it’s a negative number, but that’s the most you can expect to see.

Minus signs are missing. Expenses are deductions from sales revenue, but hardly ever do you see minus signs in front of expense amounts to indicate that they are deductions. Forget about minus signs in income statements, and in other financial statements as well. Sometimes parentheses are put around a deduction to signal that it’s a negative number, but that’s the most you can expect to see.

![]() Your eye is drawn to the bottom line. Putting a double underline under the final (bottom-line) profit number for emphasis is common practice but not universal. Instead, net income may be shown in bold type. You generally don’t see anything as garish as a fat arrow pointing to the profit number or a big smiley encircling the profit number — but again, tastes vary.

Your eye is drawn to the bottom line. Putting a double underline under the final (bottom-line) profit number for emphasis is common practice but not universal. Instead, net income may be shown in bold type. You generally don’t see anything as garish as a fat arrow pointing to the profit number or a big smiley encircling the profit number — but again, tastes vary.

![]() Profit isn’t usually called profit. As you see in Figures 4-1 and 4-2, bottom-line profit is called net income. Businesses use other terms as well, such as net earnings or just earnings. (Can’t accountants agree on anything?) In this book, I use the terms net income and profit interchangeably.

Profit isn’t usually called profit. As you see in Figures 4-1 and 4-2, bottom-line profit is called net income. Businesses use other terms as well, such as net earnings or just earnings. (Can’t accountants agree on anything?) In this book, I use the terms net income and profit interchangeably.

![]() You don’t get details about sales revenue. The sales revenue amount in an income statement is the combined total of all sales during the year; you can’t tell how many different sales were made, how many different customers the company sold products or services to, or how the sales were distributed over the 12 months of the year. (Public companies are required to release quarterly income statements during the year, and they include a special summary of quarter-by-quarter results in their annual financial reports; private businesses may or may not release quarterly sales data.) Sales revenue does not include sales and excise taxes that the business collects from its customers and remits to the government.

You don’t get details about sales revenue. The sales revenue amount in an income statement is the combined total of all sales during the year; you can’t tell how many different sales were made, how many different customers the company sold products or services to, or how the sales were distributed over the 12 months of the year. (Public companies are required to release quarterly income statements during the year, and they include a special summary of quarter-by-quarter results in their annual financial reports; private businesses may or may not release quarterly sales data.) Sales revenue does not include sales and excise taxes that the business collects from its customers and remits to the government.

Note: In addition to sales revenue from selling products and/or services, a business may have income from other sources. For instance, a business may have earnings from investments in marketable securities. In its income statement, investment income goes on a separate line and is not commingled with sales revenue. (The businesses featured in Figures 4-1 and 4-2 do not have investment income.)

![]() Gross margin matters. The cost of goods sold expense is the cost of products sold to customers, the sales revenue of which is reported on the sales revenue line. The idea is to match up the sales revenue of goods sold with the cost of goods sold and show the gross margin (also called gross profit), which is the profit before other expenses are deducted. The other expenses could in total be more than gross margin, in which case the business would have a net loss for the period. (A bottom-line loss usually has parentheses around it to emphasize that it’s a negative number.)

Gross margin matters. The cost of goods sold expense is the cost of products sold to customers, the sales revenue of which is reported on the sales revenue line. The idea is to match up the sales revenue of goods sold with the cost of goods sold and show the gross margin (also called gross profit), which is the profit before other expenses are deducted. The other expenses could in total be more than gross margin, in which case the business would have a net loss for the period. (A bottom-line loss usually has parentheses around it to emphasize that it’s a negative number.)

Note: Companies that sell services rather than products (such as airlines, movie theaters, and CPA firms) do not have a cost of goods sold expense line in their income statements, as I mention earlier. Nevertheless some service companies report a cost of sales expense, and these businesses may also report corresponding gross margin line of sorts. This is one more example of the variation in financial reporting from business to business.

![]() Operating costs are lumped together. The broad category selling, general, and administrative expenses (refer to Figure 4-1) consists of a wide variety of costs of operating the business and making sales. Some examples are:

Operating costs are lumped together. The broad category selling, general, and administrative expenses (refer to Figure 4-1) consists of a wide variety of costs of operating the business and making sales. Some examples are:

• Labor costs (employee wages and salaries, plus retirement benefits, health insurance, and payroll taxes paid by the business)

• Insurance premiums

• Property taxes on buildings and land

• Cost of gas and electric utilities

• Travel and entertainment costs

• Telephone and Internet charges

• Depreciation of operating assets that are used more than one year (including buildings, land improvements, cars and trucks, computers, office furniture, tools and machinery, and shelving)

• Advertising and sales promotion expenditures

• Legal and audit costs

As with sales revenue, you don’t get much detail about operating expenses in a typical income statement.

Your job: Asking questions!

The worst thing you can do when presented with an income statement is to be a passive reader. You should be inquisitive. An income statement is not fulfilling its purpose unless you grab it by its numbers and start asking questions.

In the product business example shown in Figure 4-1, expenses such as labor costs and advertising expenditures are buried in the all-inclusive selling, general, and administrative expenses line. (If the business manufactures the products it sells instead of buying them from another business, a good part of its annual labor cost is included in its cost of goods sold expense.) Some companies disclose specific expenses such as advertising and marketing costs, research and development costs, and other significant expenses. In short, income statement expense disclosure practices vary considerably from business to business.

Another set of questions you should ask in reading an income statement concern the profit performance of the business. Refer again to the product company’s profit performance report (refer to Figure 4-1). Profit-wise, how did the business do? Underneath this question is the implicit question: relative to what? Generally speaking, three sorts of benchmarks are used for evaluating profit performance:

![]() Broad, industry-wide performance averages

Broad, industry-wide performance averages

![]() Immediate competitors’ performances

Immediate competitors’ performances

![]() The business’s own performance in recent years

The business’s own performance in recent years

Finding Profit

As I say in the previous section, when reading an income statement your job is asking pertinent questions. Here’s an important question: What happened to the product company’s financial condition as the result of earning $1.69 million net income for the year (refer to Figure 4-1)? The financial condition of a business consists of its assets on the one side and its liabilities and owners’ equity on the other side. (The financial condition of a business at a point in time is reported in its balance sheet, which I discuss in detail in Chapter 5.)

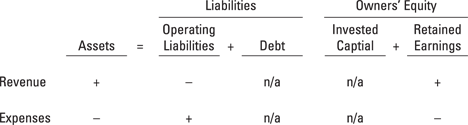

To phrase the question a little differently: How did the company’s assets, liabilities, and owners’ equity change during the year as the result of its revenue and expense transactions that yielded $1.69 million profit? Revenue and expenses are not ephemeral things, like smoke blowing in the wind. These two components of profit cause real changes in assets and liabilities. Figure 4-3 summarizes the effects of recording revenue on the one hand, and expenses on the opposite hand. A business may also record again, which has the same effect as revenue (that is, an increase in an asset or a decrease in a liability). And a business may record a loss in addition to its normal operating expenses. A loss has the same effect as an expense (that is, a decrease in an asset or an increase in a liability).

Figure 4-3: Financial effects of revenue and expenses.

In Figure 4-3 I expand the accounting equation (Assets = Liabilities + Owners’ Equity) by separating two distinct kinds of liabilities and two distinct sources of owners’ equity. Certain liabilities emanate naturally out of the normal operating activities of the business, from buying things on credit and delaying payment for expenses. These are called operating liabilities. Debt is from borrowing money. Interest is paid on debt; interest is not paid on operating liabilities. Debt can run for many months or years; operating liabilities are generally payable in 30 to 120 days.

Owners’ equity comes from two sources. The first source is capital invested in the business by its shareowners at the start of the business, and from time to time thereafter if the business needs more capital from its owners. The second source is profit earned by the business that is not distributed, or paid out to its owners. The retention of profit increases the owners’ equity of the business. The second source of owners’ equity is called retained earnings. (For more information on this term see the sidebar “So, why is it called retained earnings?”.)

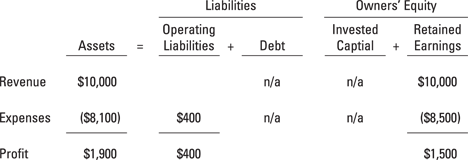

Expenses are the opposite of revenue, as Figure 4-3 shows. In recording an expense an asset is decreased or an operating liability is increased. Expenses also decrease retained earnings of course. Figure 4-4 shows an example where the business recorded $10,000 revenue (or $10,000,000 rounded off if you prefer). We assume that the business does not collect money in advance from its customers, so all the revenue for the period was recorded by increases in assets. If the business had no expenses its retained earnings would have increased $10,000 during the period (see the increase in this owners’ equity account Figure 4-4). But, of course, the business did have expenses.

The business recorded $8,500 in expenses during the period, so notice that retained earnings decreases this amount. The $8,500 in expenses had the impact of decreasing assets $8,100 and increasing operating liabilities $400. Don’t overlook the fact that expenses impact both assets and operating liabilities.

The bottom line, as we say in the business world, is that the business earned $1,500 profit. Check out the profit line in Figure 4-4. Retained earnings increased $1,500. What’s the makeup of this profit? Assets increased $1,900 (good) and operating liabilities increased $400 (bad), for a net positive effect of $1,500, the amount of profit for the period. Whew! Even this simple example takes several steps to understand. But that’s the nature of profit. You can’t get around the fact that assets and operating liabilities change in the process of making profit. The next section explores in more detail which particular assets and operating liabilities are involved in recording revenue and expenses. Later in the chapter I discuss gains and losses (in the section “Reporting Extraordinary Gains and Losses”).

Figure 4-4: Example of financial effects of making profit through end of year.

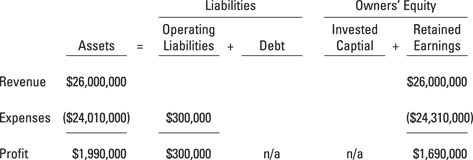

The product business in the Figure 4-1 example earned $1.69 million profit for the year. Therefore, its retained earnings increased this amount because the bottom-line amount of net income for the period is recorded in this owners’ equity account. We know this for sure, but what we can’t tell from the income statement is how the assets and operating liabilities of the business were affected by its sale and expense activities during the period.

To summarize, the product company’s $1.69 million net income resulted in some combination of changes in its assets and operating liabilities, such that its owners’ equity (specifically, retained earnings) increased $1.69 million. One such scenario is given in Figure 4-5, which reflects the company’s profit-making activities through the end of the year. By year end most of the operating liabilities that were initially recorded for expenses have been paid, which is reflected in the $24,010,000 decrease in assets. Still, operating liabilities did increase $300,000 during the year. Cash has not yet been used to pay these liabilities. I discuss these changes in more detail later in the chapter (see the section “Summing Up the Diverse Financial Effects of Making Profit”).

Figure 4-5: Financial changes from its profit-making activities through end of year for product company example.

Getting Particular about Assets and Operating Liabilities

The sales and expense activities of a business involve inflows and outflows of cash, as I’m sure you know. What you may not know, however, is that the profit-making process of a business that sells products on credit also involves four other basic assets and three basic types of operating liabilities. Each of the following sections explains one of these assets and operating liabilities. This gives you a better understanding of what’s involved in making profit and how profit-making activities change the financial make up of a business.

Making sales on credit → Accounts receivable asset

Many businesses allow their customers to buy their products or services on credit. They use an asset account called accounts receivable to record the total amount owed to the business by its customers who have made purchases “on the cuff” and haven’t paid yet. In most cases, a business doesn’t collect all its receivables by the end of the year, especially for credit sales that occur in the last weeks of the year. It records the sales revenue and the cost of goods sold expense for these sales as soon as a sale is completed and products are delivered to the customers. This is one feature of the accrual basis of accounting, which records revenue when sales are made and records expenses when these costs are incurred.

When sales are made on credit, the accounts receivable asset account is increased; later, when cash is received from the customer, cash is increased and the accounts receivable account is decreased. Collecting the cash is the follow-up transaction trailing along after the sale is recorded. So, there is a two-step process: Make the sale, and Collect cash from the customer. Through the end of the year the amount of cash collections may be less than the total recorded sales revenue, in which case the accounts receivable asset account increases from the start to the end of the period. The amount of the asset increase had not been collected in cash by the end of the year. Cash flow is lower by the amount of the asset increase.

Selling products → Inventory asset

The cost of goods sold is one of the primary expenses of businesses that sell products. (In Figure 4-1, notice that this expense is equal to more than half the sales revenue for the year.) This expense is just what its name implies: the cost that a business pays for the products it sells to customers. A business makes profit by setting its sales prices high enough to cover the costs of products sold, the costs of operating the business, interest on borrowed money, and income taxes (assuming that the business pays income tax), with something left over for profit.

When the business acquires a product, the cost of the product goes into an inventory asset account (and, of course, the cost is either deducted from the cash account or added to a liability account, depending on whether the business pays with cash or buys on credit). When a customer buys that product, the business transfers the cost of the product from the inventory asset account to the cost of goods sold expense account because the product is no longer in the business’s inventory; the product has been delivered to the customer.

The first layer in the income statement of a product company is deducting the cost of goods sold expense from the sales revenue for the goods sold. Almost all businesses that sell products report the cost of goods sold as a separate expense in their income statements, as you see in Figure 4-1. Most report this expense as shown in Figure 4-1 so that gross margin is reported. But some product companies simply report cost of goods sold as one expense among many and do not call attention to gross margin. For example, Ford Motor and General Mills (think Cheerios) do not report gross margin.

So, the cost of goods sold expense involves two steps: the products to be sold are purchased or manufactured; later, the products are sold at which time the expense is recorded. A business may acquire more products than it sells during the year. In this case the inventory asset account increases by the cost of the unsold products. The cost of goods sold expense would have an albatross around its neck, as it were — the increase in inventory of products not yet sold by the end of the period.

Prepaying operating costs → Prepaid expense asset

Prepaid expenses are the opposite of unpaid expenses. For example, a business buys fire insurance and general liability insurance (in case a customer who slips on a wet floor or is insulted by a careless salesperson sues the business). Insurance premiums must be paid ahead of time, before coverage starts. The premium cost is allocated to expense in the actual periods benefited. At the end of the year, the business may be only halfway through the insurance coverage period, so it charges off only half the premium cost as an expense. (For a six-month policy, you charge one-sixth of the premium cost to each of the six months covered.) So at the time the premium is paid, the entire amount is recorded in the prepaid expenses asset account, and for each month of coverage, the appropriate fraction of the cost is transferred to the insurance expense account.

Another example of something initially put in the prepaid expenses asset account is when a business pays cash to stock up on office supplies that it may not use for several months. The cost is recorded in the prepaid expenses asset account at the time of purchase; when the supplies are used, the appropriate amount is subtracted from the prepaid expenses asset account and recorded in the office supplies expense account.

Using the prepaid expenses asset account is not so much for the purpose of reporting all the assets of a business, because the balance in the account compared with other assets and total assets is typically small. Rather, using this account is an example of allocating costs to expenses in the period benefited by the costs, which isn’t always the same period in which the business pays those costs. The prepayment of these expenses lays the groundwork for continuing operations seamlessly into the next year.

So, for some expenses there is a two-step process: the expenses paid for in advance and the cost of the advance payment is allocated to expense over time. As with inventory, a business may prepay more than is recorded as expense during the period, in which case the prepaid expenses asset account increases.

Fixed assets → Depreciation expense

Long-term operating assets that are not held for sale in the ordinary course of business are called generically fixed assets; these include buildings, machinery, office equipment, vehicles, computers and data-processing equipment, shelving and cabinets, and so on. Depreciation refers to spreading out the cost of a fixed asset over the years of its useful life to a business, instead of charging the entire cost to expense in the year of purchase. That way, each year of use bears a share of the total cost. For example, autos and light trucks are typically depreciated over five years; the idea is to charge a fraction of the total cost to depreciation expense during each of the five years. (The actual fraction each year depends on which method of depreciation used, which I explain in Chapter 7.)

Take a look back at the product company example in Figure 4-1. From the information supplied in its income statement, we don’t know how much depreciation expense the business recorded in 2013. However, the footnotes to its financial statements reveal this amount. In 2013, the business recorded $775,000 depreciation expense. Basically, this expense decreases the book value (the recorded value) of its depreciable assets. Chapter 5 goes into more detail regarding how depreciation expense is recorded.

Unpaid expenses → Accounts payable, accrued expenses payable, and income tax payable

A typical business pays many expenses after the period in which the expenses are recorded. Following are some common examples:

![]() A business hires a law firm that does a lot of legal work during the year, but the company doesn’t pay the bill until the following year.

A business hires a law firm that does a lot of legal work during the year, but the company doesn’t pay the bill until the following year.

![]() A business matches retirement contributions made by its employees but doesn’t pay its share until the following year.

A business matches retirement contributions made by its employees but doesn’t pay its share until the following year.

![]() A business has unpaid bills for telephone service, gas, electricity, and water that it used during the year.

A business has unpaid bills for telephone service, gas, electricity, and water that it used during the year.

Accountants use three different types of liability accounts to record a business’s unpaid expenses:

![]() Accounts payable: This account is used for items that the business buys on credit and for which it receives an invoice (a bill). For example, your business receives an invoice from its lawyers for legal work done. As soon as you receive the invoice, you record in the accounts payable liability account the amount that you owe. Later, when you pay the invoice, you subtract that amount from the accounts payable account, and your cash goes down by the same amount.

Accounts payable: This account is used for items that the business buys on credit and for which it receives an invoice (a bill). For example, your business receives an invoice from its lawyers for legal work done. As soon as you receive the invoice, you record in the accounts payable liability account the amount that you owe. Later, when you pay the invoice, you subtract that amount from the accounts payable account, and your cash goes down by the same amount.

![]() Accrued expenses payable: A business has to make estimates for several unpaid costs at the end of the year because it hasn’t received invoices or other types of bills for them. Examples of accrued expenses include the following:

Accrued expenses payable: A business has to make estimates for several unpaid costs at the end of the year because it hasn’t received invoices or other types of bills for them. Examples of accrued expenses include the following:

• Unused vacation and sick days that employees carry over to the following year, which the business has to pay for in the coming year

• Unpaid bonuses to salespeople

• The cost of future repairs and part replacements on products that customers have bought and haven’t yet returned for repair

• The daily accumulation of interest on borrowed money that won’t be paid until the end of the loan period

Without invoices to reference, you have to examine your business operations carefully to determine which liabilities of this sort to record.

![]() Income tax payable: This account is used for income taxes that a business still owes to the IRS at the end of the year. The income tax expense for the year is the total amount based on the taxable income for the entire year. Your business may not pay 100 percent of its income tax expense during the year; it may owe a small fraction to the IRS at year’s end. You record the unpaid amount in the income tax payable account.

Income tax payable: This account is used for income taxes that a business still owes to the IRS at the end of the year. The income tax expense for the year is the total amount based on the taxable income for the entire year. Your business may not pay 100 percent of its income tax expense during the year; it may owe a small fraction to the IRS at year’s end. You record the unpaid amount in the income tax payable account.

Note: A business may be organized legally as a pass-through tax entity for income tax purposes, which means that it doesn’t pay income tax itself but instead passes its taxable income on to its owners. Chapter 8 explains these types of business entities. The example I offer here is for a business that is an ordinary corporation that pays income tax.

Summing Up the Diverse Financial Effects of Making Profit

The profit-making activities of a business include more than just recording revenue and expenses. Additional transactions are needed, which take place before or after revenue and expenses occur. These before-and-after transactions include the following:

![]() Collecting cash from customers for credit sales made to them, which takes place after recording the sales revenue

Collecting cash from customers for credit sales made to them, which takes place after recording the sales revenue

![]() Purchasing (or manufacturing) products that are put in inventory and held there until the products are sold sometime later, at which time the cost of products sold is charged to expense in order to match up with the revenue from the sale

Purchasing (or manufacturing) products that are put in inventory and held there until the products are sold sometime later, at which time the cost of products sold is charged to expense in order to match up with the revenue from the sale

![]() Paying certain costs in advance of when they are charged to expense

Paying certain costs in advance of when they are charged to expense

![]() Paying for products bought on credit and for other items that are not charged to expense until sometime after the purchase

Paying for products bought on credit and for other items that are not charged to expense until sometime after the purchase

![]() Paying for expenses that have been recorded sometime earlier

Paying for expenses that have been recorded sometime earlier

![]() Making payments to the government for income tax expense that has already been recorded

Making payments to the government for income tax expense that has already been recorded

To sum up, the profit-making activities of a business include both making sales and incurring expenses as well as the various transactions that take place before and after the occurrence of revenue and expenses. Only revenue and expenses are reported in the income statement; however, the other transactions change assets and liabilities, and they definitely affect cash flow. I explain how the changes in assets and liabilities caused by the allied transactions affect cash flow in Chapter 6.

Figure 4-6 is a summary of the changes in assets and operating liabilities through the end of the year caused by the product company’s profit-making activities. Keep in mind that these changes include the sales and expense transactions and the preparatory and follow-through transactions. This sort of summary can be prepared for business managers, but is not presented in external financial reports.

Figure 4-6: Here’s an example of changes in assets and operating liabilities from profit-making activities through end of year for product company (dollar amounts in thousands).

Notice the differences in Figure 4-6 compared with the earlier accounting equation-based figures. The columns for debt and owners’ equity-invested capital are not included because these two are not affected by the profit-making activities of the business. In other words, making profit affects only assets, operating liabilities, and retained earnings. The bottom line in Figure 4-6 shows that the $1,990,000 total increase in assets minus the $300,000 total increase in operating liabilities equals the $1,690,000 profit for the year.

With the summary in Figure 4-6 you can find profit. The summary reveals what profit consists of, or the substance of profit based on the profit-making activities of the business. The $1,515,000 increase in cash is the largest component of profit for the year, and the other changes in assets and operating liabilities fill out the rest of the picture. The business is $1,690,000 better off from earning that much profit. This better offness is distributed over five assets and three liabilities. You can’t look only to cash. You have to look at the other changes as well.

Reporting Extraordinary Gains and Losses

I have a small confession to make: The income statement examples shown in Figures 4-1 and 4-2 are sanitized versions when compared with actual income statements in external financial reports. Suppose you took the trouble to read 100 income statements. You’d be surprised at the wide range of things you’d find in these statements. But I do know one thing for certain you would discover.

Many businesses report unusual, extraordinary gains and losses in addition to their usual revenue, income, and expenses. Remember that recording a gain increases an asset or decreases a liability. And, recording a loss decreases an asset or increases a liability. When a business has recorded an extraordinary gain or loss during the period, its income statement is divided into two sections:

![]() The first section presents the ordinary, continuing sales, income, and expense operations of the business for the year.

The first section presents the ordinary, continuing sales, income, and expense operations of the business for the year.

![]() The second section presents any unusual, extraordinary, and nonrecurring gains and losses that the business recorded in the year.

The second section presents any unusual, extraordinary, and nonrecurring gains and losses that the business recorded in the year.

The road to profit is anything but smooth and straight. Every business experiences an occasional discontinuity — a serious disruption that comes out of the blue, doesn’t happen regularly or often, and can dramatically affect its bottom-line profit. In other words, a discontinuity is something that disturbs the basic continuity of its operations or the regular flow of profit-making activities.

Here are some examples of discontinuities or out of left field types of impacts:

![]() Downsizing and restructuring the business: Layoffs require severance pay or trigger early retirement costs; major segments of the business may be disposed of, causing large losses.

Downsizing and restructuring the business: Layoffs require severance pay or trigger early retirement costs; major segments of the business may be disposed of, causing large losses.

![]() Abandoning product lines: When you decide to discontinue selling a line of products, you lose at least some of the money that you paid for obtaining or manufacturing the products, either because you sell the products for less than you paid or because you just dump the products you can’t sell.

Abandoning product lines: When you decide to discontinue selling a line of products, you lose at least some of the money that you paid for obtaining or manufacturing the products, either because you sell the products for less than you paid or because you just dump the products you can’t sell.

![]() Settling lawsuits and other legal actions: Damages and fines that you pay — as well as awards that you receive in a favorable ruling — are obviously nonrecurring extraordinary losses or gains (unless you’re in the habit of being taken to court every year).

Settling lawsuits and other legal actions: Damages and fines that you pay — as well as awards that you receive in a favorable ruling — are obviously nonrecurring extraordinary losses or gains (unless you’re in the habit of being taken to court every year).

![]() Writing down (also called writing off) damaged and impaired assets: If products become damaged and unsellable, or fixed assets need to be replaced unexpectedly, you need to remove these items from the assets accounts. Even when certain assets are in good physical condition, if they lose their ability to generate future sales or other benefits to the business, accounting rules say that the assets have to be taken off the books or at least written down to lower book values.

Writing down (also called writing off) damaged and impaired assets: If products become damaged and unsellable, or fixed assets need to be replaced unexpectedly, you need to remove these items from the assets accounts. Even when certain assets are in good physical condition, if they lose their ability to generate future sales or other benefits to the business, accounting rules say that the assets have to be taken off the books or at least written down to lower book values.

![]() Changing accounting methods: A business may decide to use a different method for recording revenue and expenses than it did in the past, in some cases because the accounting rules (set by the authoritative accounting governing bodies — see Chapter 2) have changed. Often, the new method requires a business to record a one-time cumulative effect caused by the switch in accounting method. These special items can be huge.

Changing accounting methods: A business may decide to use a different method for recording revenue and expenses than it did in the past, in some cases because the accounting rules (set by the authoritative accounting governing bodies — see Chapter 2) have changed. Often, the new method requires a business to record a one-time cumulative effect caused by the switch in accounting method. These special items can be huge.

![]() Correcting errors from previous financial reports: If you or your accountant discovers that a past financial report had an accounting error, you make a catch-up correction entry, which means that you record a loss or gain that had nothing to do with your performance this year.

Correcting errors from previous financial reports: If you or your accountant discovers that a past financial report had an accounting error, you make a catch-up correction entry, which means that you record a loss or gain that had nothing to do with your performance this year.

According to financial reporting standards, a business must make these one-time losses and gains very visible in its income statement. So in addition to the main part of the income statement that reports normal profit activities, a business with unusual, extraordinary losses or gains must add a second layer to the income statement to disclose these out-of-the-ordinary happenings.

If a business has no unusual gains or losses in the year, its income statement ends with one bottom line, usually called net income (which is the situation shown in Figures 4-1 and 4-2). When an income statement includes a second layer, that line becomes net income from continuing operations before unusual gains and losses. Below this line, each significant, nonrecurring gain or loss appears.

Say that a business suffered a relatively minor loss from quitting a product line and a very large loss from a major lawsuit whose final verdict went against the business. The second layer of the business’s income statement would look something like the following (in thousands of dollars):

|

Net income from continuing operations |

$267,000 |

|

Discontinued operations, net of income taxes |

($20,000) |

|

Earnings before effect of legal verdict |

$247,000 |

|

Loss due to legal verdict, net of income taxes |

($456,000) |

|

Net earnings (loss) |

($209,000) |

![]() Were the annual profits reported in prior years overstated?

Were the annual profits reported in prior years overstated?

![]() Why wasn’t the loss or gain recorded on a more piecemeal and gradual year-by-year basis instead of as a one-time charge?

Why wasn’t the loss or gain recorded on a more piecemeal and gradual year-by-year basis instead of as a one-time charge?

![]() Was the loss or gain really a surprising and sudden event that could not have been anticipated?

Was the loss or gain really a surprising and sudden event that could not have been anticipated?

![]() Will such a loss or gain occur again in the future?

Will such a loss or gain occur again in the future?

![]() Discontinuities become continuities: This business makes an extraordinary loss or gain a regular feature on its income statement. Every year or so, the business loses a major lawsuit, abandons product lines, or restructures itself. It reports “nonrecurring” gains or losses from the same source on a recurring basis.

Discontinuities become continuities: This business makes an extraordinary loss or gain a regular feature on its income statement. Every year or so, the business loses a major lawsuit, abandons product lines, or restructures itself. It reports “nonrecurring” gains or losses from the same source on a recurring basis.

![]() A discontinuity is used as an opportunity to record all sorts of write-downs and losses: When recording an unusual loss (such as settling a lawsuit), the business opts to record other losses at the same time, and everything but the kitchen sink (and sometimes that, too) gets written off. This so-called big-bath strategy says that you may as well take a big bath now in order to avoid taking little showers in the future.

A discontinuity is used as an opportunity to record all sorts of write-downs and losses: When recording an unusual loss (such as settling a lawsuit), the business opts to record other losses at the same time, and everything but the kitchen sink (and sometimes that, too) gets written off. This so-called big-bath strategy says that you may as well take a big bath now in order to avoid taking little showers in the future.

A business may just have bad (or good) luck regarding extraordinary events that its managers could not have predicted. If a business is facing a major, unavoidable expense this year, cleaning out all its expenses in the same year so it can start off fresh next year can be a clever, legitimate accounting tactic. But where do you draw the line between these accounting manipulations and fraud? All I can advise you to do is stay alert to these potential problems.

Correcting Common Misconceptions About Profit

Many people (perhaps the majority) think that the amount of the bottom-line profit increases cash by the same amount. This is not true, as I show in Figure 4-6 and as I explain in Chapter 6. In almost all situations the assets and operating liabilities used in recording profit had changes during the period that inflate or deflate cash flow from profit. This is not an easy lesson to learn. Sure, it would be simpler if profit equals cash flow, but it doesn’t. Sorry, but that’s the way it is.

Another broad misconception about profit is that the numbers reported in the income statement are precise and accurate and can be relied on down to the last dollar. Call this the exactitude misconception. Virtually every dollar amount you see in an income statement probably would have been different if a different accountant had been in charge. I don’t mean that some accountants are dishonest and deceitful. It’s just that business transactions can get very complex and require forecasts and estimates. Different accountants would arrive at different interpretations of the “facts” and, therefore, record different amounts of revenue and expenses. Hopefully the accountant keeps consistent over time, so that year-to-year comparisons are valid.

Another serious misconception is that if profit is good, the financial condition of the business is good. At the time of writing this sentence the profit of Apple is very good. But I didn’t automatically assume that its financial condition was equally good. I looked in Apple’s balance sheet and found that its financial condition is very good indeed. (It had more cash and marketable investments on hand than the economy of many countries.) But, the point is that its bottom line doesn’t tell you anything about the financial condition of the business. You find this in the balance sheet.

Closing Comments

The income statement occupies center stage; the bright spotlight is on this financial statement because it reports profit or loss for the period. But remember that a business reports three primary financial statements — the other two being the balance sheet and the statement of cash flows, which I discuss in the next two chapters. The three statements are like a three-ring circus. The income statement may draw the most attention, but you have to watch what’s going on in all three places. As important as profit is to the financial success of a business, the income statement is not an island unto itself.

I don’t like closing this chapter on a sour note, but I must point out that an income statement you read and rely on — as a business manager, investor, or lender — may not be true and accurate. In most cases (I’ll even say in the large majority of cases), businesses prepare their financial statements in good faith, and their profit accounting is honest. They may bend the rules a little, but basically their accounting methods are within the boundaries of GAAP even though the business puts a favorable spin on its profit number.

By the way, look at Figure 4-6 again. This summary provides a road map of sorts for understanding accounting fraud. The fraudster knows that he has to cover up and conceal his accounting fraud. Suppose the fraudster wants to make reported profit higher. But how? The fraudster has to overstate revenue or understate expenses. And, he has to overstate one of the assets or understate one of the operating liabilities you see in Figure 4-6. The crook cannot simply jack up revenue or downsize an expense. To keep things in order the fraudster has to balance the error in the income statement with an error in an asset or operating liability. If revenue is overstated, for example, most likely the ending balance of receivables is overstated the same amount.

I wish I could say that financial reporting fraud doesn’t happen very often, but the number of high-profile accounting fraud cases over the recent decade (and longer in fact) has been truly alarming. The CPA auditors of these companies did not catch the accounting fraud, even though this is one purpose of an audit. Investors who relied on the fraudulent income statements ended up suffering large losses.

Anytime I read a financial report, I keep in mind the risk that the financial statements may be “stage managed” to some extent — to make year-to-year reported profit look a little smoother and less erratic, and to make the financial condition of the business appear a little better. Regretfully, financial statements don’t always tell it as it is. Rather, the chief executive and chief accountant of the business fiddle with the financial statements to some extent. I say much more about this tweaking of a business’s financial statements in later chapters.

For comparison

For comparison  I want to point out a few things about income statements that accountants assume everyone knows but, in fact, are not obvious to many people. (Accountants do this a lot: They assume that the people using financial statements know a good deal about the customs and conventions of financial reporting, so they don’t make things as clear as they could.) For an accountant, the following facts are second nature:

I want to point out a few things about income statements that accountants assume everyone knows but, in fact, are not obvious to many people. (Accountants do this a lot: They assume that the people using financial statements know a good deal about the customs and conventions of financial reporting, so they don’t make things as clear as they could.) For an accountant, the following facts are second nature: So why is it called retained earnings?

So why is it called retained earnings? Every company that stays in business for more than a couple of years experiences a discontinuity of one sort or another. But beware of a business that takes advantage of discontinuities in the following ways:

Every company that stays in business for more than a couple of years experiences a discontinuity of one sort or another. But beware of a business that takes advantage of discontinuities in the following ways: