Chapter 2

Financial Statements and Accounting Standards

In This Chapter

![]() Fleshing out the three key financial statements

Fleshing out the three key financial statements

![]() Noting the difference between profit and cash flow

Noting the difference between profit and cash flow

![]() Finding answers in the financial statements

Finding answers in the financial statements

![]() Knowing the nature of accounting standards

Knowing the nature of accounting standards

Chapter 1 presents a brief introduction to the three primary business financial statements: the income statement, the balance sheet, and the statement of cash flows. In this chapter, you get more interesting tidbits about these three financials, as they’re sometimes called. Then, in Part II, you really get the goods. Remember when you were learning to ride a bicycle? Chapter 1 is like getting on the bike and learning to keep your balance. In this chapter, you put on your training wheels and start riding. Then, when you’re ready, the chapters in Part II explain all 21 gears of the financial statements bicycle, and then some.

In this chapter, I explain that net income, which is the bottom-line profit of a business reported in its income statement, does not produce cash flow of the same amount. Profit-making activities cause many changes in the financial condition of a business — not just in the cash account. Many people assume that making a profit increases a business’s cash balance by the same amount, and that’s the end of it. Making profit leaves many footprints on the financial condition of a business, which you learn in this chapter.

Also in this chapter, I briefly discuss financial accounting and reporting standards. Businesses should comply with established accounting standards that govern the recording of revenue, income, expenses, and losses; put values on assets and liabilities; and present and disclose information in financial reports. The basic idea is that all businesses should follow uniform methods for measuring and reporting profit performance, and reporting financial condition and cash flows. Consistency in accounting from business to business is the goal. I explain who makes the rules, and I discuss important recent developments: the internationalization of accounting standards, and the increasing divide between financial reporting by public and private companies.

Introducing the Basic Content of Financial Statements

This chapter focuses on the basic information components of each financial statement reported by a business. In this first step, I don’t address the grouping of these information packets within each financial statement. The first step is to get a good idea of the information content reported in financial statements. The second step is to become familiar with more details about the “architecture,” rules of classification, and other features of financial statements, which I explain in Part II of the book.

Realizing that form follows function in financial statements

You need realistic business examples to understand the three primary financial statements. The information content of a business’s financial statements depends on whether the business sells products or services. For example, the financial statements of a movie theater chain are different from those of a bank, which are different from those of an airline, which are different from an automobile manufacturer. Here, I use two examples that fit a wide variety of businesses.

The first example is a business that sells products. The second example is for a business that sells services. Note that the two financial statements differ to some degree — not entirely, but in some important respects. The point is that the form of its financial statements follows the function of the business and how it makes profit — whether the business sells products or services to bring in the needed revenue to cover expenses and to provide enough profit after expenses.

Here are the particulars about the product business example:

![]() It sells products to other businesses (not on the retail level).

It sells products to other businesses (not on the retail level).

![]() It sells on credit, and its customers take a month or so before they pay.

It sells on credit, and its customers take a month or so before they pay.

![]() It holds a fairly large stock of products awaiting sale (its inventory).

It holds a fairly large stock of products awaiting sale (its inventory).

![]() It owns a wide variety of long-term operating assets that have useful lives from 3 to 30 years or longer (building, machines, tools, computers, office furniture, and so on).

It owns a wide variety of long-term operating assets that have useful lives from 3 to 30 years or longer (building, machines, tools, computers, office furniture, and so on).

![]() It has been in business for many years and has made a consistent profit.

It has been in business for many years and has made a consistent profit.

![]() It borrows money for part of the total capital it needs.

It borrows money for part of the total capital it needs.

![]() It’s organized as a corporation and pays federal and state income taxes on its annual taxable income.

It’s organized as a corporation and pays federal and state income taxes on its annual taxable income.

![]() It has never been in bankruptcy and is not facing any immediate financial difficulties.

It has never been in bankruptcy and is not facing any immediate financial difficulties.

The product company’s annual income statement for the year just ended, its balance sheet at the end of the year, and its statement of cash flows for the year are presented in following the sections.

For comparison, financial statements are also presented for a service company. This company doesn’t sell products, and it makes no sales on credit; cash is collected at the time of making sales. These are the two main differences compared with the product company.

The financial statement examples for the product and service businesses are stepping-stone illustrations that are concerned mainly with the basic information components in each statement. Full-blown, classified financial statements are presented in Part II of the book. (I know you are anxious to get to those chapters.) The financial statements in this chapter do not include all the information you see in actual financial statements. Also, I use descriptive labels for each item rather than the terse and technical titles you see in actual financial statements. And I strip out most subtotals that you see in actual financial statements because they are not necessary at this point. So, with all these caveats in mind, let’s get going.

Income statements

The income statement is the all-important financial statement that summarizes the profit-making activities of a business over a period of time. Figure 2-1 shows the basic information content of the external income statement for our product company example. External means that the financial statement is released outside the business to those entitled to receive it — primarily its shareowners and lenders. Internal financial statements stay within the business and are used mainly by its managers; they are not circulated outside the business because they contain competitive and confidential information.

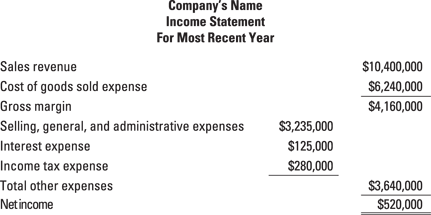

Figure 2-1: Income statement for a business that sells products.

Income statement for a product company

Figure 2-1 presents the major ingredients of the income statement for a product company. As you might expect, it starts with sales revenue on the top line. Then the cost of the products (goods) sold is deducted from sales revenue to report gross margin (also called gross profit), which is a preliminary, or “first” line, measure of profit before other expenses are taken into account. Next other types of expenses are listed, and their total is deducted from gross margin to reach the final bottomline, called net income. Virtually all income statements disclose at least these four expenses. (A business can report more types of expenses in its external income statement, and many do.)

Cost of goods sold expense and selling, general, and administrative expenses take the biggest bites out of sales revenue. The other two expenses (interest and income tax) are relatively small as a percent of annual sales revenue but important enough in their own right to be reported separately. And though you may not need this reminder, bottom-line profit (net income) is the amount of sales revenue in excess of its total expenses. If either sales revenue or any of the expense amounts are wrong, then profit is wrong. (I will harp on this point throughout the book.)

Income statement for a service company

Figure 2-2 presents the income statement for a company that sells services (instead of products). I keep this example the same dollar size as the product company. Notice that annual sales revenue is $10,400,000 for both companies. And, I keep total expenses the same at $9,880,000. (For the product company its $6,240,000 cost of goods sold expense plus its $3,640,000 of other expenses is $9,880,000.) Therefore, net income for both companies is $520,000.

Figure 2-2: Income statement for a business that sells services.

The service business does not sell a product; therefore, it does not have the cost of goods sold expense, and accordingly does not report a gross margin line in its income statement. In place of cost of goods sold it has other types of expenses. In Figure 2-2 operating expenses are $6,240,000 in place of cost of goods sold expense. Service companies differ on how they report their operating expenses. For example, United Airlines breaks out the cost of aircraft fuel, and landing fees. The largest expense of the insurance company State Farm is payments on claims. The movie chain AMC reports film exhibition costs separate from its other operating expenses.

Income statement pointers

Inside most businesses an income statement is called a P&L (profit and loss) report. These internal profit performance reports to the managers of a business include a good deal more detailed information about expenses and about sales revenue also. Reporting just four expenses to managers (as shown in Figures 2-1 and 2-2) would not do. Chapter 9 explains P&L reports to managers.

Sales revenue is from the sales of products or services to customers. You also see the term income, which generally refers to amounts earned by a business from sources other than sales; for example, a real estate rental business receives rental income from its tenants. (In the two examples for a product and a service company, the businesses have only sales revenue.)

Net income, being the bottom line of the income statement after deducting all expenses from sales revenue (and income, if any), is called, not surprisingly, the bottom line. It is also called net earnings. A few companies call it profit or net profit, but such terminology is not common.

The income statement gets the most attention from business managers, lenders, and investors (not that they ignore the other two financial statements). The much abbreviated versions of income statements that you see in the financial press, such as in TheWall Street Journal, report the top line (sales revenue and income) and the bottom line (net income) and not much more. Refer to Chapter 4 for more information on income statements.

Balance sheets

A more accurate name for a balance sheet is statement of financial condition, or statement of financial position. But the term balance sheet has caught on, and most people use this term. Keep in mind that the “balance” is not important, but rather the information reported in this financial statement. In brief, a balance sheet summarizes on the one hand the assets of the business and on the other hand the sources of the assets. The sources have claims, or entitlements against the assets of the business. Looking at assets is only half the picture. The other half consists of the liabilities and owner equity claims on the assets. Cash is listed first and other assets are listed in the order of their nearness to cash. Liabilities are listed in order of their due dates (the earliest first, and so on). Liabilities are listed ahead of owners’ equity.

Balance sheet for a product company

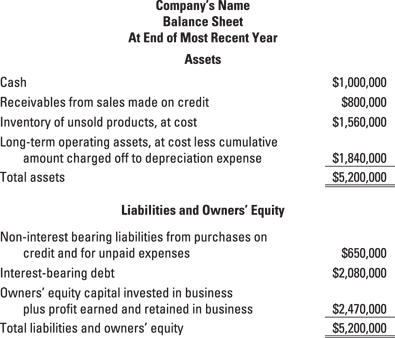

Figure 2-3 shows the building blocks (basic information components) of a typical balance sheet for a business that sells products on credit. One reason the balance sheet is called by this name is that its two sides balance, or are equal in total amounts. In the example, the $5.2 million total of assets equals the $5.2 million total of liabilities and owners’ equity. The balance or equality of total assets on the one side of the scale and the sum of liabilities plus owners’ equity on the other side of the scale is expressed in the accounting equation, which I discuss in Chapter 1. Note: the balance sheet example shown in Figure 2-3 concentrates on the essential elements in this financial statement. In a financial report the balance sheet includes additional features and frills, which I explain in Chapter 5.

Figure 2-3: Balance sheet for a company that sells products on credit.

Let’s take a quick walk through the balance sheet (Figure 2-3). For a company that sells products on credit, assets are reported in the following order: First is cash; then receivables; then cost of products held for sale; and finally the long-term operating assets of the business. Moving to the other side of the balance sheet, the liabilities section starts with the trade liabilities (from buying on credit) and liabilities for unpaid expenses. Following these operating liabilities is the interest-bearing debt of the business. Owners’ equity sources are then reported below liabilities. Each of these information packets is called an account — so a balance sheet has a composite of asset accounts, liability accounts, and owners’ equity accounts.

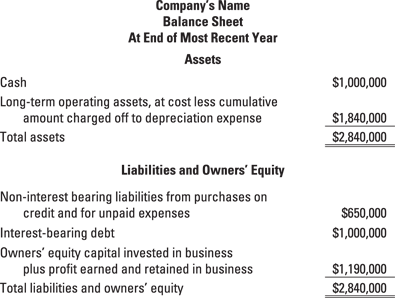

Balance sheet for a service company

Figure 2-4 presents the typical balance sheet components for a business that sells services (instead of products). Recall that the service company example does not sell on credit; it collects cash at the point of sale. Notice right away that this service business example does not have two sizable assets that the product company has — receivables from credit sales and inventory of products held for sale. Therefore, the total assets of our service company example are considerably smaller. The product company has $5,200,000 total assets (Figure 2-3), whereas the service company has only $2,840,000 total assets (Figure 2-4).

Figure 2-4: Balance sheet for a service company.

The smaller amount of total assets of the service business means that the other side of its balance sheet is correspondingly smaller as well. In plain terms, this means that the service company does not need to borrow as much money or raise as much capital from its equity owners compared with the product business. Notice, for example, that the interest-bearing debt of the service company is $1.0 million (Figure 2-4) compared with over $2.0 million for the product company (Figure 2-3). Likewise, the total amount of owners’ equity for the service business is much smaller than the product company.

Balance sheet pointers

Businesses need a variety of assets. You have cash, of course, which every business needs. When selling on credit, a business records a receivable that is collected later (typically 30 days or longer). Businesses that sell products carry an inventory of products awaiting sale to customers. Businesses need long-term resources that have the generic name property, plant, and equipment; this group includes buildings, vehicles, tools, machines, and other resources needed in their operations. All these, and more, go under the collective name “assets.”

As you might suspect, the particular assets reported in the balance sheet depend on which assets the business owns. I include just four basic types of assets in Figure 2-3. These are the hardcore assets that a business selling products on credit would have. It’s possible that such a business could lease (or rent) virtually all of its long-term operating assets instead of owning them, in which case the business would report no such assets. In this example, the business owns these so-called fixed assets. They are fixed because they are held for use in the operations of the business and are not for sale, and their usefulness lasts several years or longer.

So, where does a business get the money to buy its assets? Most businesses borrow money on the basis of interest-bearing notes or other credit instruments for part of the total capital they need for their assets. Also, businesses buy many things on credit and at the balance sheet date, owe money to their suppliers, which will be paid in the future. These operating liabilities are never grouped with interest-bearing debt in the balance sheet. The accountant would be tied to the stake for doing such a thing. Note that liabilities are not intermingled among assets — this is a definite no-no in financial reporting. You cannot subtract certain liabilities from certain assets and only report the net balance. You would be given 20 lashes for doing so.

Could a business’s total liabilities be greater than its total assets? Well, not likely — unless the business has been losing money hand over fist. In the vast majority of cases a business has more total assets than total liabilities. Why? For two reasons:

![]() Its owners have invested money in the business.

Its owners have invested money in the business.

![]() The business has earned profit over the years, and some (or all) of the profit has been retained in the business. Making profit increases assets; if not all the profit is distributed to owners, the company’s assets rise by the amount of profit retained.

The business has earned profit over the years, and some (or all) of the profit has been retained in the business. Making profit increases assets; if not all the profit is distributed to owners, the company’s assets rise by the amount of profit retained.

The profit for the most recent period is found in the income statement; periodic profit is not reported in the balance sheet. The profit reported in the income statement is before any distributions from profit to owners. The cumulative amount of profit over the years that has not been distributed to its owners is reported in the owners’ equity section of the company’s balance sheet.

By the way, notice that the balance sheet in Figure 2-3 is presented in a top and bottom format, instead of a left and right side format. Either the vertical or horizontal mode of display is acceptable. You see both the portrait and the landscape layouts in financial reports.

Statement of cash flows

To survive and thrive, business managers confront three financial imperatives:

![]() Make an adequate profit

Make an adequate profit

![]() Keep financial condition out of trouble and in good shape

Keep financial condition out of trouble and in good shape

![]() Control cash flows

Control cash flows

The income statement reports whether the business made a profit. The balance sheet reports the financial condition of the business. The third imperative is reported on in the statement of cash flows, which presents a summary of the business’s sources and uses of cash during the income statement period.

Smart business managers hardly get the word net income (or profit) out of their mouths before mentioning cash flow. Successful business managers tell you that they have to manage both profit and cash flow; you can’t do one and ignore the other. Business managers have to deal with a two-headed dragon in this respect. Ignoring cash flow can pull the rug out from under a successful profit formula. My son, Tage, and I have coauthored Cash Flow For Dummies (John Wiley & Sons), which you may want to take a peek at.

In the statement of cash flows, the cash activity of the business during the period is grouped into the three basic types of transactions that I discuss in Chapter 1: profit-making transactions, investing transactions, and financing transactions. Figure 2-5 presents just the net cash effects of each of these three types of transactions for the product company example. These are the basic information components of the statement. The net increase or decrease in cash from the three types of cash activities during the period is added to or subtracted from the beginning cash balance to get the cash balance at the end of the year.

Figure 2-5: Statement of cash flows.

In the product company example, the business earned $520,000 profit (net income) during the year (see Figure 2-1). The result of its profit-making activities was to increase its cash $400,000, which you see in the first part of the statement of cash flows (see Figure 2-5). This still leaves $120,000 of profit to explain, which I get to in the next section. The actual cash inflows from revenues and outflows for expenses run on a different timetable than when the sales revenue and expenses are recorded for determining profit. I give a more comprehensive explanation of the differences between cash flows and sales revenue and expenses in Chapter 6.

The second part of the statement of cash flows sums up the long-term investments made by the business during the year, such as constructing a new production plant or replacing machinery and equipment. If the business sold any of its long-term assets, it reports the cash inflows from these divestments in this section of the statement of cash flows. The cash flows of other investment activities (if any) are reported in this part of the statement as well. As you can see in part of the statement of cash flows (see Figure 2-5), the business invested $450,000 in new long-term operating assets (trucks, equipment, tools, and computers).

The third part of the statement sums up the dealings between the business and its sources of capital during the period — borrowing money from lenders and raising new capital from its owners. Cash outflows to pay debt are reported in this section, as well as cash distributions from profit paid to the owners of the business. The third part of the statement reports that the result of these transactions was to increase cash $200,000 (see Figure 2-5). By the way, in this product company example, the business did not make cash distributions from profit to its owners. It probably could have, but it didn’t — which is an important point that I discuss later in the chapter (see the section “Why no cash distribution from profit?”).

I could tell you that the statement of cash flows is relatively straightforward and easy to understand, but that would be a lie. The statements of cash flows of most businesses are frustratingly difficult to read. (More about this issue in Chapter 6.) Actual cash flow statements have much more detail than the brief introduction to this financial statement in Figure 2-5.

I do not present the statement of cash flows for the service company example, mainly because it would look virtually the same as for the product company example, except that the cash effect for each type of cash activity would be different amounts. Two factors can cause the cash flow from profit-making (operating) activities of a product company to swing widely from its bottom-line profit: changes in receivables, and changes in inventory. A service company does not have these two assets, so its cash flow from profit holds on a steadier course with profit.

A note about the statement of changes in shareowners’ equity

Many financial reports of businesses include a fourth financial statement — or at least it’s called a “statement.” It’s really a summary of the changes in the constitute elements of owners’ equity (stockholders’ equity of a corporation). The corporation is one basic type of legal structure that businesses use. In Chapter 8 I explain the alternative legal structures available for conducting business operations. I don’t present a summary here, or statement of changes in owners’ equity. I show an example in Chapter 12, in which I explain the preparation of a financial report for release.

When a business has a complex owner’s equity structure, a separate summary of changes in the several different components of owners’ equity during the period is useful for the owners, the board of directors, and the top-level managers. On the other hand, in some cases the only changes in owners’ equity during the period were earning profit and distributing part of the cash flow from profit to owners. In this situation there is not much need for a summary of changes in owners’ equity. The financial statements reader can easily find profit in the income statement and cash distributions from profit (if any) in the statement of cash flows. See the section “Why no cash distribution from profit?” later in this chapter for the product company example.

Contrasting Profit and Cash Flow from Profit

Look again at the income statement in Figure 2-1. The product company in our example earned $520,000 net income for the year. However, its statement of cash flows for the same year in Figure 2-5 reports that its profit-making, or operating, activities increased cash only $400,000 during the year. This gap between profit and cash flow from operating activities is not unusual. So, what happened to the other $120,000 of profit? Where is it? Is there some accounting sleight of hand going on? Did the business really earn $520,000 net income if cash increased only $400,000? These are good questions, and I will try to answer them as directly as I can without hitting you over the head with a lot of technical details at this point.

Here’s one scenario that explains the $120,000 difference between profit (net income) and cash flow from profit (operating activities):

![]() Suppose the business collected $50,000 less cash from customers during the year than the total sales revenue reported in its income statement. (Remember that the business sells on credit, and its customers take time before actually paying the business.) Therefore, there’s a cash inflow lag between booking sales and collecting cash from customers. As a result, the business’s cash inflow from customers was $50,000 less than the sales revenue amount used to calculate profit for the year.

Suppose the business collected $50,000 less cash from customers during the year than the total sales revenue reported in its income statement. (Remember that the business sells on credit, and its customers take time before actually paying the business.) Therefore, there’s a cash inflow lag between booking sales and collecting cash from customers. As a result, the business’s cash inflow from customers was $50,000 less than the sales revenue amount used to calculate profit for the year.

![]() Also suppose that during the year the business made cash payments connected with its expenses that were $70,000 higher than the total amount of expenses reported in the income statement. For example, a business that sells products buys or makes the products, and then holds the products in inventory for some time before it sells the items to customers. Cash is paid out before the cost of goods sold expense is recorded. This is one example of a difference between cash flow connected with an expense and the amount recorded in the income statement for the expense.

Also suppose that during the year the business made cash payments connected with its expenses that were $70,000 higher than the total amount of expenses reported in the income statement. For example, a business that sells products buys or makes the products, and then holds the products in inventory for some time before it sells the items to customers. Cash is paid out before the cost of goods sold expense is recorded. This is one example of a difference between cash flow connected with an expense and the amount recorded in the income statement for the expense.

In this scenario, the two factors cause cash flow from profit-making (operating) activities to be $120,000 less than the net income earned for the year. Cash collections from customers were $50,000 less than sales revenue, and cash payments for expenses were $70,000 more than the amount of expenses recorded to the year. In Chapter 6, I explain the several factors that cause cash flow and bottom-line profit to diverge.

Gleaning Key Information from Financial Statements

The whole point of reporting financial statements is to provide important information to people who have a financial interest in the business — mainly its outside investors and lenders. From that information, investors and lenders are able to answer key questions about the financial performance and condition of the business. I discuss a few of these key questions in this section. In Chapters 13 and 16 I discuss a longer list of questions and explain financial statement analysis.

How’s profit performance?

Investors use two important measures to judge a company’s annual profit performance. Here, I use the data from Figures 2-1 and 2-3 for the product company. Of course you can do the same ratio calculations for the service business example. For convenience the dollar amounts here are expressed in thousands:

![]() Return on sales = profit as a percent of annual sales revenue:

Return on sales = profit as a percent of annual sales revenue:

$520 bottom-line annual profit (net income) ÷ $10,400 annual sales revenue = 5.0%

![]() Return on equity = profit as a percent of owners’ equity:

Return on equity = profit as a percent of owners’ equity:

$520 bottom-line annual profit (net income) ÷ $2,470 owners’ equity = 21.1%

Profit looks pretty thin compared with annual sales revenue. The company earns only 5 percent return on sales. In other words, 95 cents out of every sales dollar goes for expenses, and the company keeps only 5 cents for profit. (Many businesses earn 10 percent or higher return on sales.) However, when profit is compared with owners’ equity, things look a lot better. The business earns more than 21 percent profit on its owners’ equity. I’d bet you don’t have many investments earning 21 percent per year.

Is there enough cash?

Cash is the lubricant of business activity. Realistically a business can’t operate with a zero cash balance. It can’t wait to open the morning mail to see how much cash it will have for the day’s needs (although some businesses try to operate on a shoestring cash balance). A business should keep enough cash on hand to keep things running smoothly even when there are interruptions in the normal inflows of cash. A business has to meet its payroll on time, for example. Keeping an adequate balance in the checking account serves as a buffer against unforeseen disruptions in normal cash inflows.

At the end of the year, the product company in our example has $1 million cash on hand (refer to Figure 2-3). This cash balance is available for general business purposes. (If there are restrictions on how it can use its cash balance, the business is obligated to disclose the restrictions.) Is $1 million enough? Interestingly, businesses do not have to comment on their cash balance. I’ve never seen such a comment in a financial report.

The business has $650,000 in operating liabilities that will come due for payment over the next month or so (refer to Figure 2-3). So, it has enough cash to pay these liabilities. But it doesn’t have enough cash on hand to pay its operating liabilities and its $2.08 million interest-bearing debt (refer to Figure 2-2 again). Lenders don’t expect a business to keep a cash balance more than the amount of debt; this condition would defeat the very purpose of lending money to the business, which is to have the business put the money to good use and be able to pay interest on the debt.

Lenders are more interested in the ability of the business to control its cash flows, so that when the time comes to pay off loans it will be able to do so. They know that the other, non-cash assets of the business will be converted into cash flow. Receivables will be collected, and products held in inventory will be sold and the sales will generate cash flow. So, you shouldn’t focus just on cash; you should throw the net wider and look at the other assets as well.

Taking this broader approach, the business has $1 million cash, $800,000 receivables, and $1.56 million inventory, which adds up to $3.36 million of cash and cash potential. Relative to its $2.73 million total liabilities ($650,000 operating liabilities plus $2.08 million debt), the business looks in pretty good shape. On the other hand, if it turns out that the business is not able to collect its receivables and is not able to sell its products, it would end up in deep doo-doo.

$10,400,000 annual sales revenue ÷ 365 days = $28,493 sales per day

$1,000,000 cash balance ÷ $28,493 sales per day = 35 days

The business’s cash balance equals a little more than one month of sales activity, which most lenders and investors would consider adequate.

Can you trust financial statement numbers?

Whether the financial statements are correct or not depends on the answers to two basic questions:

![]() Does the business have a reliable accounting system in place and employ competent accountants?

Does the business have a reliable accounting system in place and employ competent accountants?

![]() Have its managers manipulated the business’s accounting methods or deliberately falsified the numbers?

Have its managers manipulated the business’s accounting methods or deliberately falsified the numbers?

I’d love to tell you that the answer to the first question is always yes, and the answer to the second question is always no. But you know better, don’t you?

What can I tell you? There are a lot of crooks and dishonest persons in the business world who think nothing of manipulating the accounting numbers and cooking the books. Also, organized crime is involved in many businesses. And I have to tell you that in my experience many businesses don’t put much effort into keeping their accounting systems up to speed, and they skimp on hiring competent accountants. In short, there is a risk that the financial statements of a business could be incorrect and seriously misleading.

To increase the credibility of their financial statements, many businesses hire independent CPA auditors to examine their accounting systems and records and to express opinions on whether the financial statements conform to established standards. In fact, some business lenders insist on an annual audit by an independent CPA firm as a condition of making the loan. The outside, non-management investors in a privately owned business could vote to have annual CPA audits of the financial statements. Public companies have no choice; under federal securities laws, a public company is required to have annual audits by an independent CPA firm.

Why no cash distribution from profit?

In this product company example the business did not distribute any of its profit for the year to its owners. Distributions from profit by a business corporation are called dividends. (The total amount distributed is divided up among the stockholders, hence the term “dividends.”) Cash distributions from profit to owners are included in the third section of the statement of cash flows (refer to Figure 2-5). But, in the example, the business did not make any cash distributions from profit — even though it earned $520,000 net income (refer to Figure 2-1). Why not?

The business realized $400,000 cash flow from its profit-making (operating) activities (refer to Figure 2-3). In most cases, this would be the upper limit on how much cash a business would distribute from profit to its owners. So you might very well ask whether the business should have distributed, say, at least half of its cash flow from profit, or $200,000, to its owners. If you owned 20 percent of the ownership shares of the business, you would have received 20 percent, or $40,000, of the distribution. But you got no cash return on your investment in the business. Your shares should be worth more because the profit for the year increased the company’s owners’ equity. But you did not see any of this increase in your wallet.

Keeping in Step with Accounting and Financial Reporting Standards

The unimpeded flow of capital is critical in a free market economic system and in the international flow of capital between countries. Investors and lenders put their capital to work where they think they can get the best returns on their investments consistent with the risks they’re willing to take. To make these decisions, they need the accounting information provided in financial statements of businesses.

Imagine the confusion that would result if every business were permitted to invent its own accounting methods for measuring profit and for putting values on assets and liabilities. What if every business adopted its own individual accounting terminology and followed its own style for presenting financial statements? Such a state of affairs would be a Tower of Babel.

Recognizing U.S. standards

The authoritative standards and rules that govern financial accounting and reporting by businesses in the United States are called generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). When you read the financial statements of a business, you’re entitled to assume that the business has fully complied with GAAP in reporting its cash flows, profit-making activities, and financial condition — unless the business makes very clear that it has prepared its financial statements using some other basis of accounting or has deviated from GAAP in one or more significant respects.

I won’t bore you with a lengthy historical discourse on the development of accounting and financial reporting standards in the United States. The general consensus (backed by law) is that businesses should use consistent accounting methods and terminology. General Motors and Microsoft should use the same accounting methods; so should Wells Fargo and Apple. Of course, businesses in different industries have different types of transactions, but the same types of transactions should be accounted for in the same way. That is the goal.

There are upwards of 10,000 public companies in the United States and easily more than a million private-owned businesses. Now, am I telling you that all these businesses should use the same accounting methods, terminology, and presentation styles for their financial statements? Putting it in such a stark manner makes me suck in my breath a little. The ideal answer is that all businesses should use the same rulebook of GAAP. However, the rulebook permits alternative accounting methods for some transactions. Furthermore, accountants have to interpret the rules as they apply GAAP in actual situations. The devil is in the details.

In the United States, GAAP constitute the gold standard for preparing financial statements of business entities. The presumption is that any deviations from GAAP would cause misleading financial statements. If a business honestly thinks it should deviate from GAAP — in order to better reflect the economic reality of its transactions or situation — it should make very clear that it has not complied with GAAP in one or more respects. If deviations from GAAP are not disclosed, the business may have legal exposure to those who relied on the information in its financial report and suffered a loss attributable to the misleading nature of the information.

I wish I could tell you at this point that financial reporting and accounting standards in the United States have settled down and that except for normal developments things are in a steady state. However, the mechanisms and processes of issuing and enforcing financial reporting and accounting standards are in a state of flux. The biggest changes in the works have to do with the push to internationalize the standards, and the movements toward setting different standards for private companies and for small and medium sized business entities.

Getting to know the U.S. standard setters

Okay, so everyone reading a financial report is entitled to assume that GAAP have been followed (unless the business clearly discloses that it is using another basis of accounting). The basic idea behind the development of GAAP is to measure profit and to value assets and liabilities consistently from business to business — to establish broad-scale uniformity in accounting methods for all businesses. The idea is to make sure that all accountants are singing the same tune from the same hymnal. The authoritative bodies write the tunes that accountants have to sing.

Who are these authoritative bodies? In the United States, the highest-ranking authority in the private (non-government) sector for making pronouncements on GAAP — and for keeping these accounting standards up-to-date — is the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). Also, the federal Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has broad powers over accounting and financial reporting standards for companies whose securities (stocks and bonds) are publicly traded. Actually, the SEC outranks the FASB because it derives its authority from federal securities laws that govern the public issuance and trading in securities. The SEC has on occasion overridden the FASB, but not very often.

GAAP also include minimum requirements for disclosure, which refers to how information is classified and presented in financial statements and to the types of information that have to be included with the financial statements, mainly in the form of footnotes. The SEC makes the disclosure rules for public companies. Disclosure rules for private companies are controlled by GAAP. Chapter 12 explains the disclosures that are required in addition to the three primary financial statements of a business (the income statement, balance sheet, and statement of cash flows).

Internationalization of accounting standards (maybe, maybe not)

Although it’s a bit of an overstatement, today the investment of capital knows no borders. U.S. capital is invested in European and other countries, and capital from other countries is invested in U.S. businesses. In short, the flow of capital has become international. U.S. GAAP does not bind accounting and financial reporting standards in other countries, and in fact there are significant differences that cause problems in comparing the financial statements of U.S. companies with those in Europe and other countries.

Outside the United States, the main authoritative accounting standards setter is the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB), which is based in London. The IASB was founded in 2001. Over 7,000 public companies have their securities listed on the several stock exchanges in the European Union (EU) countries. In many regards, the IASB operates in a manner similar to the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) in the United States, and the two have very similar missions. The IASB has already issued many standards, which are called International Financial Reporting Standards.

For some time the FASB and IASB have been working together toward developing global standards that all businesses would follow, regardless of which country a business is domiciled. Of course political issues and national pride come into play. The term harmonization is favored, which sidesteps difficult issues regarding the future roles of the FASB and IASB in the issuance of international accounting standards. However, the SEC recently put out a study that could delay if not kill the efforts toward one set of universal financial reporting and accounting standards. Also, the two rule-making bodies have had fundamental disagreements on certain accounting issues. I have my doubts whether a full-fledged universal set of standards will be agreed upon. Stay tuned; it’s hard to predict the final outcome.

Divorcing public and private companies

Traditionally, GAAP and financial reporting standards were viewed as equally applicable to public companies (generally large corporations) and private companies (generally smaller). Today, however, we are witnessing a growing distinction between accounting and financial reporting standards for public versus private companies. Although most accountants don’t like to admit it, there’s always been a de facto divergence in actual financial reporting practices by private companies compared with the more rigorously enforced standards for public companies. For example, a surprising number of private companies still do not include a statement of cash flows in their financial reports, even though this has been a GAAP requirement since 1975.

Private companies do not have many of the accounting problems of large, public companies. For example, many public companies deal in complex derivative instruments, issue stock options to managers, provide highly developed defined-benefit retirement and health benefit plans for their employees, enter into complicated inter-company investment and joint venture operations, have complex organizational structures, and so on. Most private companies do not have to deal with these issues.

Finally I should mention in passing that the AICPA, the national association of CPAs, has started a project to develop an Other Comprehensive Basis of Accounting for privately held small and medium sized entities. Oh boy! What a confusing time for accounting standards. The upshot seems to be that we are drifting towards separate accounting standards for larger public companies versus smaller private companies. Just how different the two sets of standards will be is open to speculation. As the Chinese proverb says: may you live in interesting times.

Following the rules and bending the rules

An often-repeated story concerns three persons interviewing for an important accounting position. They are asked one key question: “What’s 2 plus 2?” The first candidate answers, “It’s 4,” and is told, “Don’t call us, we’ll call you.” The second candidate answers, “Well, most of the time the answer is 4, but sometimes it’s 3 and sometimes it’s 5.” The third candidate answers: “What do you want the answer to be?” Guess who gets the job. This story exaggerates, of course, but it does have an element of truth.

The point is that interpreting GAAP is not cut-and-dried. Many accounting standards leave a lot of wiggle room for interpretation. Guidelines would be a better word to describe many accounting rules. Deciding how to account for certain transactions and situations requires seasoned judgment and careful analysis of the rules. Furthermore, many estimates have to be made. (See the sidebar “Depending on estimates and assumptions.”) Deciding on accounting methods requires, above all else, good faith.

Dollar amounts in financial statements are typically rounded off, either by not presenting the last three digits (when rounded off to the nearest thousand) or by not presenting the last six digits (when rounded to the nearest million by large companies). I strike a compromise on this issue — I show the last three digits for each item as 000, which means that I rounded off the amount but still show all digits. Many smaller businesses report their financial statement dollar amounts out to the last dollar, or even the last penny for that matter. Keep in mind that too many digits in a dollar amount are hard to comprehend.

Dollar amounts in financial statements are typically rounded off, either by not presenting the last three digits (when rounded off to the nearest thousand) or by not presenting the last six digits (when rounded to the nearest million by large companies). I strike a compromise on this issue — I show the last three digits for each item as 000, which means that I rounded off the amount but still show all digits. Many smaller businesses report their financial statement dollar amounts out to the last dollar, or even the last penny for that matter. Keep in mind that too many digits in a dollar amount are hard to comprehend. Oops, I forgot to mention a couple of things about financial statements. I should give you a quick heads-up on these points. Financial statements are rather stiff and formal. No slang or street language is allowed, and I’ve never seen a swear word in one. Financial statements would get a G in the movies rating system. Seldom do you see any graphics or artwork in a financial statement itself, although you do see a fair amount of photos and graphics on other pages in the financial reports of public companies. And, there’s virtually no humor in financial reports. Don’t look for cartoons like the ones by Rich Tennant in this book. (However, I might mention that in his annual letter to the stockholders of Berkshire Hathaway, Warren Buffett includes some wonderful humor to make his points.)

Oops, I forgot to mention a couple of things about financial statements. I should give you a quick heads-up on these points. Financial statements are rather stiff and formal. No slang or street language is allowed, and I’ve never seen a swear word in one. Financial statements would get a G in the movies rating system. Seldom do you see any graphics or artwork in a financial statement itself, although you do see a fair amount of photos and graphics on other pages in the financial reports of public companies. And, there’s virtually no humor in financial reports. Don’t look for cartoons like the ones by Rich Tennant in this book. (However, I might mention that in his annual letter to the stockholders of Berkshire Hathaway, Warren Buffett includes some wonderful humor to make his points.) In the product company example (refer to

In the product company example (refer to