CHAPTER 7

Cross-Cultural Communications and Virtual Teams

Today’s organizations require people at all levels who can comfortably interact with cultures other than their own. In our shrinking world, as people from various backgrounds and cultures increasingly work together, the need to communicate through a global lens becomes vital. Winning or losing competitive battles depends on operations that function productively abroad as well as at home, and that entails molding successful practices that work well across many cultures. In no area is this need for cross-cultural communication (CCC) more critical than with virtual teams. Team members bring invisible cultural roots that influence behavior around beliefs, values, perceptions, expectations, attitudes, and assumptions. Managers may find that these cultural differences pose special problems that they did not anticipate. The good news is that many virtual managers like you have developed capabilities to overcome these difficulties.

Whether team members work across the street, across the country, or across the world, issues related to CCC exist, even if they lurk in the background. Your virtual team may not be a global team, but chances are that it is a cross-cultural one, and so you have to figure out how to communicate in this world of diminished cues.

Pepper Pot Soup

When teams assemble people of diverse cultures, their differences can create misunderstandings, but commonalities can also be uncovered, as I learned. For many years I taught at New York University and ran an activity called Pepper Pot Soup. Grouped by ethnic backgrounds, students had to describe cultural traits that differentiated them from other cultures. Then I divided the class into random groups of mixed cultures; each group made a hypothetical “soup,” noting how their own cultural differences affected their soup recipe. Within the context of the workplace, for example, these differences might be around decision making, teamwork, or independence.

Every class concluded that despite our differences, we all share the most important human characteristic—the need for communication. These differences make the soup more flavorful and open up conversations. Just as ingredients add their special zest to a soup, complementary ingredients can create strong organizations.

Pepper Pot Soup got its name from a Caribbean student whose grandmother made a wonderful stew that filled the house with a peppery smell. She said this soup was not just a meal; it was also like a medicine. And then she made a perceptive remark that I have shared with every class since: Sometimes combining ingredients yields much more than the sum of their individual characteristics. The message was clear that a multicultural organization has a great deal to offer, and its members do not have to shed their differences.

Culture and Communication

At its most basic, culture refers to a group, or community, whose members share similar experiences, worldviews, and values. Up until a few generations ago, most managers worked solely with local counterparts who shared similar backgrounds. Now, in a typical workday, you probably communicate with colleagues, clients, and vendors from different parts of the globe. Language barriers and different worldviews and experiences can cause communication challenges, which can be costly if not overcome. As the pace of business transactions quickens, the ability to communicate with and manage people from other cultures becomes a requirement for success.

Culture is the way we do things. It’s how we behave as individuals and in teams. Culture is shaped by our experiences and influences the way we view and understand the world around us. It influences (1) our values and what we consider desirable/undesirable, (2) the behaviors we consider acceptable/unacceptable, (3) our morals around right/wrong, and (4) how we view and interpret the world.

Consider a group of people who share a similar background that consists of patterns of communication, viewpoints, expressions, and behaviors. Taken together, they form blueprints collectively known as cultural patterns; when people refer to other cultures, they generally refer to these cultural patterns. The danger with cultural patterns is that they can lead to stereotyping people, professions, and ethnic groups. Generalizations and stereotyping differ. Stereotypes tend to be negative statements emerging from perceptions about a few individuals that are then applied to an entire group. Generalizations are claims based on thoughtful analysis.

While stereotyping is undesirable, making generalizations about a cultural attribute can help you understand another culture, creating a foundation for a relationship. The materials and action steps presented in this chapter use these cultural generalizations as starting points to help you better understand other cultures and their stories. Please note that these generalizations are not intended to imply that everyone from a specific culture shares certain characteristics or acts the same way. No doubt, as opportunities to interact increase, we will gain greater knowledge about our cohabitants on this planet.

This chapter defines culture as including the shared mental programs that condition individuals’ responses to their environment: the collection of values, beliefs, symbols, and norms that members follow. It is based on common experiences that we share with a particular group. Furthermore, it is both learned and enduring—some aspects of culture are built into institutions, while others are passed down through generations. Last, culture is a filter that influences behavior, often in ways that elude our consciousness.

Since culture envelopes us, we adapt to it without realizing that we are doing so. When engaging cross-culturally, we know something is different, but we are often reluctant to discuss cultural characteristics, especially in business situations. And yet virtual managers need to recognize cultural characteristics and understand how they can be used productively to drive business success.

You don’t have to walk a mile (or kilometer) in someone else’s shoes—but you need to learn to communicate through a cultural lens. This chapter offers tools, tips, and techniques for effective CCC. I will also share another perspective around cultural interactions that I found particularly relevant to virtual teams.

The Intercultural Disconnect

Miscommunications can occur even when core values are shared. Imagine, then, how many more obstacles we face when communicating with parties from different cultural backgrounds. Before we dive into strategies to offset these potential issues, here’s an example of how misunderstanding cultural cues can lead to unwarranted conclusions.

Scenario: Will You Hire Him?

Bocci’s Tool and Die Company, located in San Diego, California, is hiring three production workers. The recruiter is ready to screen his next applicant. Suddenly the door opens and a dark-skinned young man walks in. Without a glance at the recruiter he finds the nearest chair and, without waiting to be invited, sits down. Making no eye contact with the recruiter, he stares at the floor. The recruiter (born and raised in the United States) is appalled at what he deems inappropriate behavior. Even though the job requires manual dexterity, and strong social skills are not needed, this young man has no chance to meet the production manager. He is cut from the applicant pool before he can step inside the factory door.

You can see how an individual’s cultural background affects behavior and perceptions. Most Americans would find this young man’s behavior strange or rude. However, he is Samoan, and in his culture it is not appropriate to speak to, or even make eye contact with, authority figures until they invite you to do so. You do not stand while they are sitting, because to do so would put you on a physically higher level than they are, implying serious disrespect. Viewed through his cultural lens, the young man behaved appropriately.

This example illustrates how a person’s cultural background (or “cultural lens,” as I refer to it) affects behavior and perceptions. Intercultural situations present many opportunities for us to misconstrue others’ intentions and in turn embarrass ourselves or our coworkers. This happens because we are often unaware of our own cultural biases. We can also feel threatened or uneasy when interacting with people from different cultures, especially if we are unfamiliar with behaviors that seem inappropriate in a given situation.

The Four Communication Challenges in the Virtual Environment

Let’s look more closely at some challenges presented by CCC and the potential for miscommunication.

1. Lack of Informal Communication. On-site coworkers have the advantage of communicating informally through the grapevine. Although grapevines may have a dark side, such as allowing rumors to circulate, they do serve a valuable social function. Grapevines give managers and staff a source to tap into information that may not be circulated upward and a channel to leak information downward. Virtual teams that communicate primarily by e-mail have fewer options for informal communication, which means fewer opportunities to correct wrong impressions.

2. Differences in Perception. Psychological noise occurs when the message receiver perceives a different meaning from what the sender intended. How different individuals perceive the same sensory information can vary tremendously, which may result in faulty communication. A further challenge in a virtual environment is the need to constantly double-check how well our message was understood.

3. Differences in Status. People occupying different levels on the organizational hierarchy may have difficulty communicating with each other for various reasons. Managers may not adequately value the knowledge of lower-status employees, and these employees may resist sharing negative information with managers, especially if the manager is from another culture.

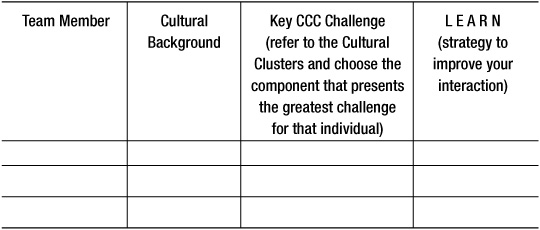

4. Differences in Interpreting Context. In some cultures the words alone convey an individual’s intention, while in other cultures the context of the message provides cues that are just as important as the expressed words. In high-context cultures, context plays a large part in how to interpret a message, while in low-context cultures the words themselves are most important in interpreting a message.

Individuals from low-context cultures typically lack skill in noticing and interpreting background cues. They tend to talk more and depend on verbal rather than nonverbal codes, and they are decidedly uncomfortable with silence. Emphasis is placed on being direct, and the person on the receiving end of the message is meant to respond accordingly. The task is more important than the relationship, so low-context speakers will use clear language, and lots of it, to get their point across.

Individuals from high-context cultures place emphasis on trust and rely on nonverbal communication, so they tend to be less verbal and more comfortable with silence and reading between the lines. Often the words are identical to those from low-context cultures, but another meaning is attached to them. For example, a Japanese businessman might say “yes” when asked if he agrees with a proposal, but in reality he is merely conveying his own understanding—he does not mean that a deal is imminent.

Figure 7-1 shows the world’s major cultures on a scale from high to low context.

Figure 7-1. Context scale of different cultures.

Language Is My Starting Point

All cross-cultural interactions occur through written or oral language. Therefore, when coaching managers of cross-cultural teams, language is my starting point, since it is the basis of communication. After team members identify their country of origin, we look at their cultural characteristics, paying close attention to commonalities and differences in language. We discuss how language can lead to misunderstandings and possibly to conflict. Together we create a plan that considers the types of misunderstandings that arise from these differences and some concrete ways to lessen their negative impact on the team’s performance.

Consider the following scenario of a client engagement with a major international telecom firm, where I was brought in to help with interpersonal issues that caused slippage in key target dates during the quality control (QC) stage of a new billing system.

CASE STUDY

“They’re So Nice, It’s Too Much”

Ted, the virtual team manager, coordinated weekly team meetings from his office in New York without having met any of his overseas team members in person except for a brief meeting in Bangalore with a team led by Kumar. “They’re so nice,” Ted told me, “that it’s too much. I told Kumar to let me know ASAP if he had a problem, since we have some pretty tough characters on our team. I had a sense early on that I wouldn’t know what was really going on there because some unpleasant e-mails were directed at [Kumar’s] team and he didn’t explain what happened or defend the developers or even ask for a more civil tone in future e-mails.”

Ted asked me to silently participate on a teleconference call held to brainstorm ways to connect this diverse team. Team members checked in from India, Israel, and other cities in the United States, across many time zones: There were developers from San Francisco, contractors from Bangalore and Haifa, and QC specialists from Atlanta. Here is a summary of what transpired during this call:

• Ted kicked off the meeting by welcoming everyone, and then he detailed the issues related to the software.

• One of the developers from California asserted: The bottom line is that we are the customer.

• Someone on the India team followed that comment with this one: Of course you are the customer. As the conversation continued, it was clear that India-based team members were very polite and subservient, almost too polite, constantly apologizing for any mistakes.

• Israeli team members found every opportunity to repeat: That was not our responsibility. California team members methodically asked for documentation for activities and specific time lines.

When the call ended, I debriefed the meeting with Ted. He summed up his team’s characteristics in this way:

American Team’s Cultural Characteristics

• They don’t think in terms of only black or only white; everything is a shade of gray.

• When a question is asked about an issue they don’t know about, team members will say, “Sorry, I don’t know, but give me some time to check.”

• Generally they don’t make a commitment until things are in place.

Indian Team’s Cultural Characteristics

• Everyone is extremely polite and subservient in how they talk to us.

• When I get off our weekly conference call, I never know what they really think.

• During our teleconferences, they come across as extremely status conscious.

• They apologize for any mistake, even if it’s a minor grammatical error.

Israeli Team’s Cultural Characteristics

• Everything is a negotiation with them, whereas with India it’s “Yes sir.”

• They come across to their peers in California as very rude, almost to the point that if the client wasn’t getting a good deal they’d consider dropping them as a vendor.

• They think in terms of black or white, not gray.

• They don’t know how not to answer. They will commit first and check later whether it’s possible.

Knowing that these cultural characteristics created problems around communication and accomplishing goals, I worked with the team (approximately a dozen members) to come up with a series of initiatives, some of which were easy to roll out immediately and some that would require extensive planning.

1. Each team member picked a partner from another region and committed to one phone call each week to discuss one difficult aspect of the project. The call was to last ten to fifteen minutes, and certain ground rules were to be observed: The conversations would take place within a zone of trust, meaning that no one could show impatience at any time. They would be mutually respectful of each other. Questions had to be specific, with concrete answers in response. And, finally, each call would end with an invitational phrase, such as: “What else would you like me to know about XYZ?”

2. Team members agreed to raise the level and frequency of communication about deliverables and due dates. They also committed to pointing out what wasn’t clear at the time the interaction occurred.

3. To help deal with cultural differences, the team would exchange members for temporary assignments of three to six months, whenever possible, with Haifa and Bangalore exchanging representatives with Atlanta and San Francisco, respectively.

4. Although travel throughout the division was kept to a minimum, each location would send one representative team member to New York for a two-day meeting every six months. Agenda and criteria for selection would be determined later.

Within the next few months things improved. The team created general guidelines for communicating across the diverse cultures represented on the team. Each week one team member was assigned, on a rotating basis, to summarize the call, noting in a group e-mail the issue, deadline, and responsible party. I was happily surprised when they came up with the idea of devoting the first five minutes of their calls to have one team member, again on a rotating basis, teach the others about one aspect of that person’s culture—a holiday, a tradition, or an important event.

CASE STUDY

Pay Close Attention …

Language differences entwined with cultural nuances create some interesting situations. Alex, an interviewee who manages a virtual team of data analysts, told me this story about a frustrating situation that he resolved with a workaround:

“I manage a team of five people, so there are usually six of us on any given call. Three of my guys are in Romania, another Romanian is in Florida, and I work in Sydney with the fifth member of my team. When I first managed the team I decided to start each week with a conference call, and that the time would vary to accommodate the different time zones.

“I’ll never forget my first call, when I wanted to welcome everyone. I asked George, one analyst in Romania, how he was doing and he said he was fine, so I next asked Aurel, who worked with [George], how he was. But Aurel didn’t answer, so I said something like, ‘Can you hear me? Are you there?’ Silence. ‘Are you there?’ I repeated. Still no answer. So I asked George [who was in the conference room with Aurel] why Aurel didn’t respond. He said, ‘Because he does not have a microphone.’ But I knew they were both at the same conference table, and I assumed they were sitting right next to each other, so I couldn’t understand why George just didn’t pass the microphone to him—it’s no big deal, but they were so literal in their thinking. I was talking to Aurel, so George didn’t think it was his place to help out. They lost the commonsense aspect to communicating because they were busy interpreting my exact words. I realized that it was better to use chat and any type of written communication with the Romanian team instead of the phone. If I write something that is unclear, they can look up the meaning in the dictionary and have a written record of it.

“I see this same issue in India and Russia, where they take things literally to a degree that someone more fluent in English doesn’t, but they do the specifics of their own jobs really well and with a great attention to detail. For example, if I were to say ‘Cut this tree down,’ they will do it well and precisely, but if I say, ‘Cut a circular driveway,’ they don’t get it. They’re great at zeroing in on the details but flounder when it comes to the big picture.

“It’s all about how information is interpreted. Part of it is cultural, part of it is not being in the same room, and part of it is language. My answer for this is to pay close attention to make sure they understand my intention, and to know where they are at any given point on an analysis, especially when a big deadline looms.”

Alex’s commonsense lessons are worth repeating for virtual managers:

• Pay close attention both to what is being said and to the cultural nuances that team members bring with them. Just as Alex came to understand that he had to hear his own words through the cultural lens of the colleagues with whom he spoke, you have to consider how your words are interpreted by each member of your team. Avoid colloquialisms and keep your instructions specific.

• Know which communication mode to use with each team member. As Alex discovered, written communication worked best with some team members.

• To this advice I would also add that when deadlines are close or situations are critical, you need to check in more frequently and ask appropriate questions to keep the workflow on track. You may be asking for A and getting B, and things can get lost in translation.

When Things Get Lost in Translation

In the virtual world, even when you and your cross-cultural partner speak the same language, it’s possible to get lost in translation. This occurs when (1) different meanings are attached to the same words, causing interpretations to vary, and (2) a common expression in one culture is a non sequitur in another. Without clarifying your intention, these misunderstandings can snowball.

I know firsthand how English words may have dual meanings, as an incident with a client that occurred during the planning stage of this book shows. My client was a retail company with several overseas locations. As part of a group e-mail, my office manager and I often requested information about customized materials. In response to a request she made about printing training guides locally, she received this e-mail: “As you demanded, I am sending information about the printing schedule.”

She quickly dashed off her own e-mail: “Just for the record, and for your own communication in English, saying ‘as you demanded’ is not PC! LOL. ‘As per your request’ would sound much better.”

She received this response: “What is PC? Are you referring to our computers?”

At that point she phoned our contact and clarified the difference between the words demand and request; in addition, she explained that PC in this instance meant politically correct, not a computer. Fortunately, we all had a good laugh and agreed to take extra care with future e-mails.

Virtual Teams Translate English to English

As we have seen, the mix of cultures can cause various obstacles to communication. According to my virtual teams study (see Figure 7-2), the most common difficulty pertains to differences in understanding the English language (as indicated by 47 percent of survey respondents). There are difficulties related to levels of competency, differences in interpretations, literal translation issues, lack of language skills (as happens when team members are hired for technical expertise), and accents. As you can see from the stories shared by my interviewees, even words such as yes or done can mean different things in certain cultures.

Figure 7-2. Global obstacles to communication.

You may have seen firsthand that differences in cultures lead to alternate interpretations of events as well as words. Expressions and idioms that are ingrained in one culture lose their meaning when translated and may cause misunderstandings, even if/when we speak the same language. The same holds true for jargon and humor, additional layers that add complexity in cross-cultural communication. Sometimes people from different cultures may not even realize that a difficulty exists, and that’s when things really get complicated. Here are some stories from my personal experience and from numerous interviews about situations when things got lost in translation. Perhaps you have experienced something similar on your virtual team.

Saying Yes. One of my clients who worked for a bookseller told of a particularly frustrating situation with a web design vendor. Diane was located in New Jersey while the vendor was in India. Prior to a big launch, Diane held weekly calls with the designers to review agenda items, projected due dates, and potential issues. Her questions were always met with a pleasant, earnest “Yes,” but deadlines continually slipped and calls and e-mails were not answered. She was forced to place multiple calls and send numerous e-mails to learn how the project was progressing. Finally, after many frustrating weeks she realized there was a cultural disconnect—yes means one thing for Americans and another for their Indian colleagues. For them, yes means “I heard you,” while it means “I’ll get it done” to an American.

Saying No. Barbara, a virtual leader at a global technology IPO, offered this story:

“Part of our due diligence was to create a marketing plan to support our business strategy for different cultures. When I did a combination of in-person and virtual interviews with folks in the Asia/Pacific region, I found out that in many oriental cultures there simply isn’t a word for no. The market research firm that designed a survey had yes/no answers, and we didn’t realize that the resulting data was skewed. Everyone answered ‘yes’ and it took us a while to realize that.”

Barbara continued with an interesting experience that she had in Tokyo:

“At a meeting with senior executives, my chair was placed in the middle of the room—there was no table—with all the other chairs set in a half-moon around me. I sat there with all eyes on me, feeling interrogated, but from their perspective I was given a place of honor. The translator answered my questions ‘yes,’ but I could see them shake their heads ‘no.’ Their body language also said ‘no.’ It hadn’t occurred to me that they were saying yes but not meaning it until I saw it with my own eyes. At that point we redid the survey using only multiple-choice questions. If I hadn’t gone to Singapore and Tokyo, I wouldn’t have noticed this cultural disconnect.

“I learned that on virtual teams you must be very explicit in your communications and constantly hold daily calls at certain times. If we don’t do that, productivity levels off. I pick a specific issue or question and then ask everyone to weigh in. I’m a big believer in using a 1 to 5 scale to pinpoint what I’m trying to find out. I keep it simple, with 5 [being] the best. I say, ‘How is [fill in the blank]? Is it more like a 4 or 5, or just a 1 or 2?’”

“Okay, We Got It.” Arlene, a client who works from a home office in Connecticut managing a virtual team for a pharmaceutical giant, told me the following story:

“My number-one issue when I communicate with my virtual team members is understanding their accents on the phone. I deal with people from China, South Africa, India, and Costa Rica, and I often can’t understand what they say, and sometimes it’s worse with tech teams. There are additional issues that come up with our developers in India. When they first joined my team I would lay out deadlines and describe specs, and no matter what I said they would say, ‘Okay, we got it,’ and ‘Yes, we’re okay,’ but things were not okay and they weren’t delivered on time. It didn’t take me long to realize that they said ‘okay’ instead of asking questions.

“So I kept very detailed notes of what I wanted to accomplish on each call, and for important points I asked them to repeat back what I said. It went like this: I would say, ‘I need to make sure you deliver [this expected result or product] by [date].’ After giving them a few seconds to think it over I would then say, ‘What did I just ask for?’ Someone would shoot back, ‘ABC,’ and I would then say, ‘No, it’s XYZ.’ We went back and forth until I was satisfied that what I conveyed was understood and would be acted on in a timely manner. But it didn’t stop there. I then followed up the phone call with an e-mail. All this took a lot longer than I was used to, but I got the results I wanted.”

What Can You Take Away from These Situations?

As a virtual manager you may have faced similar issues and have put in place similar solutions, which are based on common sense and respect for others. Although the specifics of these three situations differ and the virtual managers come from different industries, they all shared the need to understand and to be understood by others. Keeping the communication clean so that things don’t get lost in translation is one of your key responsibilities, especially when business English is the “part-time” language of many team members. The three managers adapted to the cultural cues, and I am confident that by following their suggestions, you will have the same success with your team:

1. Keep detailed notes of what you need accomplished on calls so that you are clear at all times on how the virtual meeting is progressing.

2. Conduct frequent check-ins where everyone voices an opinion.

3. When you ask a question, use a Likert scale of 1 to 5 with specific, explicit choices (strongly disagree, disagree, neither agree nor disagree, agree, or strongly agree). Ask open-ended questions; don’t provide informative answers.

4. Ask team members to repeat what you said to ensure understanding.

5. Follow up with phone calls and e-mails, and be as explicit as possible.

What Do I Do if They Don’t Speak My Language?

Being foreign-born, I am always sensitive to how I speak, especially when interacting with people from other cultures. In these circumstances, I keep an open mind, sharpen my “people antenna” to get a better read of the situation, and ask questions. I am always willing to learn about other cultures, and I make an effort to understand what someone else’s language means.

Here are some suggestions for what to do when people don’t speak your language.

If You Are the Non-native Speaker

![]() Appreciate that your strong accent, for example, may make it difficult for others to understand you. You can say something like, “I know that I have a strong accent. Please do not hesitate to interrupt me whenever something is unclear to you, or ask me to repeat what I said more slowly.”

Appreciate that your strong accent, for example, may make it difficult for others to understand you. You can say something like, “I know that I have a strong accent. Please do not hesitate to interrupt me whenever something is unclear to you, or ask me to repeat what I said more slowly.”

If You Are the Native Speaker

![]() Be aware that you may slip into colloquialisms, talk very fast, mumble, or speak with a regional accent, all of which hinder a non-native speaker’s comprehension. Therefore, it is helpful to speak slowly and say up front, “If necessary, please stop me and ask me to repeat something or ask for a further explanation.”

Be aware that you may slip into colloquialisms, talk very fast, mumble, or speak with a regional accent, all of which hinder a non-native speaker’s comprehension. Therefore, it is helpful to speak slowly and say up front, “If necessary, please stop me and ask me to repeat something or ask for a further explanation.”

![]() Keep in mind the dangers of using slang, particularly with people whose English is their part-time language because they may not always understand the meaning behind the expression. For example, Americans often use the term slam dunk without realizing that even fluent speakers of English from other cultures are not aware of its meaning as a “sure thing.”

Keep in mind the dangers of using slang, particularly with people whose English is their part-time language because they may not always understand the meaning behind the expression. For example, Americans often use the term slam dunk without realizing that even fluent speakers of English from other cultures are not aware of its meaning as a “sure thing.”

Additional Tips

![]() Cue your verbal and nonverbal behaviors to your audience.

Cue your verbal and nonverbal behaviors to your audience.

![]() Repeat! Yes, repeat important ideas and explain the concept with different words.

Repeat! Yes, repeat important ideas and explain the concept with different words.

![]() Check comprehension by asking colleagues to repeat their understanding of the material back to you. Do not assume your audience understands what you say. Don’t just ask, “Do you understand what I mean?” Ask them to explain what they heard, in their own words.

Check comprehension by asking colleagues to repeat their understanding of the material back to you. Do not assume your audience understands what you say. Don’t just ask, “Do you understand what I mean?” Ask them to explain what they heard, in their own words.

![]() Pause more frequently.

Pause more frequently.

![]() When there is a silence, wait. Do not jump in to fill the silence. The other person is probably just translating your words.

When there is a silence, wait. Do not jump in to fill the silence. The other person is probably just translating your words.

![]() Do not equate poor grammar and mispronunciation with lack of intelligence; it is usually a sign of second-language use.

Do not equate poor grammar and mispronunciation with lack of intelligence; it is usually a sign of second-language use.

![]() On long conference calls, take more frequent breaks. Second-language comprehension can be exhausting.

On long conference calls, take more frequent breaks. Second-language comprehension can be exhausting.

![]() Divide your presentation into small modules with frequent checkpoints so that listeners don’t fall behind.

Divide your presentation into small modules with frequent checkpoints so that listeners don’t fall behind.

![]() E-mail team members summaries of your verbal presentation.

E-mail team members summaries of your verbal presentation.

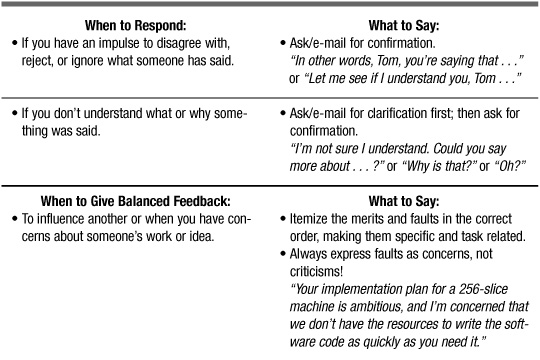

The Five Clusters That Comprise All Cross-Cultural Interactions

Given that people from different cultures view the world and events through their own cultural lens (just see how many different definitions of virtual team your team members would come up with if asked), understanding cultural nuances is an overriding consideration. Since virtual teams, by definition, comprise individuals from different locations, there is a good chance that your team will also have people from a variety of cultures. Although it is tempting to overlook these differences, by doing so you run the risk of causing needless friction that can impact team performance.

My consulting practice has spanned various industries and locales, and over the years engagements have taken me all over the world. I realized that regardless of how a team was organized or the nature of its mission, themes emerged around how team members interact. That is, within every culture certain factors consistently appear when people work together. For clarity and consistency, I have grouped these factors into what I call clusters (five in all) that comprise cross-cultural interactions. Team members are usually selected because of their technical skills, without considering how cultural backgrounds may affect team interactions. And yet, as you saw in Chapter 6, technical skills alone will not get deliverables out the door if miscommunications and perceived slights occur that can derail efforts. By examining these clusters, you will understand the specific aspects of culture that can lead to these difficulties.

The five clusters are:

1. Mindset

2. Persona

3. Orientation

4. Structure

5. Process

Within each cluster, think about the cultural styles represented on your team, and the preferences individuals show, which are derived from their culture of origin. Note that most behaviors fall along a continuum, and there is no right or wrong.

In my experience, managers produce high-performing teams when they consider the unique cultural perspectives of team members. Use this awareness of how culture impacts behavior across the five clusters to encourage appropriate team interactions. Ask yourself how you can build on differences to pull individuals together into a successful team. Or, as I like to say, how can you combine these wonderful ingredients to make a great Pepper Pot Soup?

Cluster 1: Mindset (the “What”)

“The biggest difference between American and Asian cultures is collaboration. It wasn’t until I worked on a post-merger implementation with my Asian counterparts that I came up against their culture. They are very collaborative and they work to complete what the boss wants. I don’t like to assign tasks, I like my team to speak up and ask questions. I don’t care if we disagree—that energizes me. But I had to initiate discussions and challenge the process because they wouldn’t challenge someone more senior.”

—VT LEADER, INSURANCE COMPANY

Mindset refers to our underlying assumptions, beliefs, and attitudes about the world; it’s how we make sense of what our senses take in, and is heavily influenced by the culture around us. Mindset guides our thinking process and behavior, and becomes ingrained through repetition, which reinforces our initial responses.

Mindset encompasses the following factors:

![]() Global vs. Local Perspective. What lens do you use to view the world? Do you have a short-focus or a wide-angle lens? Some people look at their immediate surroundings, favoring close colleagues and focusing on what’s good for their immediate group. Others take a broader approach and look beyond their own comfort zone to include various perspectives.

Global vs. Local Perspective. What lens do you use to view the world? Do you have a short-focus or a wide-angle lens? Some people look at their immediate surroundings, favoring close colleagues and focusing on what’s good for their immediate group. Others take a broader approach and look beyond their own comfort zone to include various perspectives.

![]() Collaborative vs. Competitive. Think about your attitude and underlying assumptions when interacting with other people. Do you approach things in a more participative way, seeking input from others, or do you have “sharp elbows” when advocating strongly for your own point of view?

Collaborative vs. Competitive. Think about your attitude and underlying assumptions when interacting with other people. Do you approach things in a more participative way, seeking input from others, or do you have “sharp elbows” when advocating strongly for your own point of view?

![]() Consultative vs. Decisive. While a preference for collaborating or competing speaks to our attitudes, a decisive or consultative approach directly relates to the process of how we make decisions and go about solving problems. Do you consult others and strive for consensus, or do you “decide and announce” a plan, without input from others?

Consultative vs. Decisive. While a preference for collaborating or competing speaks to our attitudes, a decisive or consultative approach directly relates to the process of how we make decisions and go about solving problems. Do you consult others and strive for consensus, or do you “decide and announce” a plan, without input from others?

![]() Task-Oriented vs. Relationship-Oriented. Which comes first, the relationship or the task? Do you focus on developing the relationship before conducting business, or do you go straight to the issues at hand without building the relationships that make success possible?

Task-Oriented vs. Relationship-Oriented. Which comes first, the relationship or the task? Do you focus on developing the relationship before conducting business, or do you go straight to the issues at hand without building the relationships that make success possible?

Cluster 2: Persona (the “Who”)

“I often travel to Santo Domingo on business. On my first trip, I asked a question and I would get an answer that had no basis in reality. For example, if I asked, ‘How long does it take to get from A to B?’ I would be told ten minutes, but it was really an hour away. Everything was ten minutes because no one wanted any negativity; nothing was too hard to do, nothing was too far away. So I started asking questions in a more general way, like, ‘If you were going to [this place], how long would it take to get there?’ or ‘When would you leave here to get to [that place]?’ The trick was not to ask the question as if I was considering going there myself. Then I would get the truth.”

—BEVERAGE COMPANY EXECUTIVE

What face do you put forward when communicating? Persona is the way we present ourselves to the world and how we approach others. It is a set of behaviors that allows us to interact with someone in a culturally appropriate way. These behaviors are typically based on deeply rooted cultural norms that have shaped us from childhood. Every culture has an expected dynamic that people from that culture prefer when interacting.

Here are the key behaviors associated with Persona:

![]() Holding Opinions to Oneself vs. Voicing Opinions. Do individuals keep things to themselves or do they voice their thoughts and concerns? The answer to this question may reflect people’s personal styles as well as cultural biases. Either people have a willingness to share an opinion and hash out an issue, or they prefer to keep their thoughts private and not risk losing face.

Holding Opinions to Oneself vs. Voicing Opinions. Do individuals keep things to themselves or do they voice their thoughts and concerns? The answer to this question may reflect people’s personal styles as well as cultural biases. Either people have a willingness to share an opinion and hash out an issue, or they prefer to keep their thoughts private and not risk losing face.

![]() Agreeable vs. Willing to Disagree. During discussions, do you go along with what people say, even though you may not concur, or are you willing to openly disagree?

Agreeable vs. Willing to Disagree. During discussions, do you go along with what people say, even though you may not concur, or are you willing to openly disagree?

![]() Public or Private. Do individuals share details about their personal life or family, or are they more reticent?

Public or Private. Do individuals share details about their personal life or family, or are they more reticent?

![]() Question Authority or Acquiesce. How does one act when dealing with someone in a superior position? What face do you show? Are you willing to respectfully question authority or do you accept an authority figure’s word and think, “That’s the way it is”?

Question Authority or Acquiesce. How does one act when dealing with someone in a superior position? What face do you show? Are you willing to respectfully question authority or do you accept an authority figure’s word and think, “That’s the way it is”?

Cluster 3: Orientation (the “When”)

“I allotted thirty minutes for a gentleman from Pakistan to explain a pilot program during a conference. He spoke eloquently, but unfortunately he was extremely long-winded and spent a great deal of time thanking different people, which took time away from the core content. My boss told me to move his presentation along, so I had to ask him to wrap it up. I passed him a note which said, PLEASE—ONLY FIVE MORE MINUTES, I’M SORRY. [Afterward] I had to save face and apologize, saying that I didn’t schedule enough time for his presentation. It was an uncomfortable situation, with a lot of tension. The Canadians, Americans, and Brits felt he was wasting time and they were really annoyed. It’s still the ‘Western way is the better way’ sentiment.”

—HR EXECUTIVE, INTERNATIONAL RESCUE ORGANIZATION

Orientation is about the way that you view time and value its use. Cultural frameworks determine our view of the nature of time and, therefore, our choices around how we spend it.

Here are key components to evaluate within Orientation:

![]() Present or Future. Do you think about what’s happening right now or what’s happening in the future? In addition, is your focus on the short term or long term?

Present or Future. Do you think about what’s happening right now or what’s happening in the future? In addition, is your focus on the short term or long term?

![]() Limited or Plentiful. The issue here is related to time as a commodity. If we view each moment as unique and scarce, then time is considered to be a limited commodity that must be maximized (multitasking, anyone?). If time is renewable, like the cyclical processes of nature, then it will always be there in large quantities.

Limited or Plentiful. The issue here is related to time as a commodity. If we view each moment as unique and scarce, then time is considered to be a limited commodity that must be maximized (multitasking, anyone?). If time is renewable, like the cyclical processes of nature, then it will always be there in large quantities.

![]() Slow or Fast Pace. This issue deals with activity as it relates to time. If time is a limited commodity, then you’ll function at a faster pace, packing more activities and initiatives into your waking hours. However, cultures that take a long view of time typically function at a slower pace and are frequently characterized as patient; it is more important to participate in a process than to meet deadlines or to be punctual. Think of it as the difference between packing twenty-five hours of activities into a twenty-four-hour day and engaging in several hours’ worth of activities in the same twenty-four-hour period.

Slow or Fast Pace. This issue deals with activity as it relates to time. If time is a limited commodity, then you’ll function at a faster pace, packing more activities and initiatives into your waking hours. However, cultures that take a long view of time typically function at a slower pace and are frequently characterized as patient; it is more important to participate in a process than to meet deadlines or to be punctual. Think of it as the difference between packing twenty-five hours of activities into a twenty-four-hour day and engaging in several hours’ worth of activities in the same twenty-four-hour period.

Cluster 4: Structure (the “How to Organize”)

“When my company was bought by a world leader, I was put on a team that looked at new markets, and we had Koreans and Americans gathering data. One guy, an American from the Northeast, kept asking his Korean contact for some information, to no avail. Finally, he complained directly to a higher-level Korean manager and caused a major rift because he didn’t realize that Koreans operate in a hierarchy. The higher-level Korean manager and Korean team members were offended. We were from a small company where the only thing that mattered was getting things done. You have to learn to adjust, and I did.”

—VT MEMBER, ELECTRONICS GIANT

Structure is the approach to order and the degree of flexibility around that order. Cultures order their world according to expectations, norms, and roles. A society can be more tolerant or less tolerant of deviation, uncertainty, and disorder; its structure mirrors the extent of that tolerance.

Here are the key behavioral components to evaluate within Structure:

![]() Precise vs. Loose. Does your culture take a literal view of how order is approached? If so, there will be greater structure, with a precise order imposed from the top and highly detailed rules of behavior. At the other end of the continuum is loose structure, with fewer rules about social behavior.

Precise vs. Loose. Does your culture take a literal view of how order is approached? If so, there will be greater structure, with a precise order imposed from the top and highly detailed rules of behavior. At the other end of the continuum is loose structure, with fewer rules about social behavior.

![]() Hierarchical vs. Entrepreneurial. Is power centralized, hierarchical, and tightly defined, or is the environment more entrepreneurial and not as defined? Business organizations, among others, are structured around how centralized and hierarchical the power structure is, and how tightly defined and controlled responsibilities are within an organization. Entrepreneurial businesses or cultures, by comparison, operate in an environment where the power structure is not as defined. Here, individuals are empowered to some degree, and powersharing arrangements are common.

Hierarchical vs. Entrepreneurial. Is power centralized, hierarchical, and tightly defined, or is the environment more entrepreneurial and not as defined? Business organizations, among others, are structured around how centralized and hierarchical the power structure is, and how tightly defined and controlled responsibilities are within an organization. Entrepreneurial businesses or cultures, by comparison, operate in an environment where the power structure is not as defined. Here, individuals are empowered to some degree, and powersharing arrangements are common.

![]() Formal vs. Informal. Do people address each other formally or informally? Are titles very important or nonexistent? It is important to know answers to these questions when we do business with other cultures to avoid needless friction. Some cultures place a lot of emphasis on the formality of the interaction, while in other cultures title and status are not as important. A culture that values formality attaches significance to tradition, rules and rank, status and power, while informal cultures have a casual attitude and value more egalitarian organizations with smaller differences in status and power.

Formal vs. Informal. Do people address each other formally or informally? Are titles very important or nonexistent? It is important to know answers to these questions when we do business with other cultures to avoid needless friction. Some cultures place a lot of emphasis on the formality of the interaction, while in other cultures title and status are not as important. A culture that values formality attaches significance to tradition, rules and rank, status and power, while informal cultures have a casual attitude and value more egalitarian organizations with smaller differences in status and power.

Cluster 5: Process (the “How to Do It”)

“When I started this job we had fifty to sixty people: thirty-five in Beijing, the rest in Germany, U.K., Australia, Canada, and the U.S. I had a big task of getting them to collaborate, although I didn’t speak any other language but English. The group in Beijing was between [the ages of] 25 to 35. The rest of the people in the organization had been there longer and survived several downturns. They were in their fifties and felt that they knew it all. We had cultural clashes between the young Chinese, who were waiting for instructions, and experienced Americans/Europeans, who wanted to get the objectives and be left alone. So I hired a cultural expert and conducted cultural sensitivity training. It really helped, but the real coming together for the team was our sailing trip. One team member had a giant sailboat and took us all for a sail. Some Chinese teammates were never on a boat before, so they were happy to try something new. It was a great bonding experience—coming together as a team—and performance increased afterward. To this day, people still talk about this sailing experience. Maybe next time I’ll take them on a boat race.”

—VT LEADER, BIOCHEMICAL COMPANY

Process is how we get things done. There are multiple stages with people working together to transform ideas into actions to achieve specific goals. Process is the approach one takes in pursuit of these goals.

Here are key descriptors within Process:

![]() Planning Ahead vs. Just-in-Time. What is the value your culture places on planning, from an idea’s inception through execution to fruition? Is the culture considered methodical, where it is customary to plan ahead, with clearly defined steps of a process? Or is it a just-in-time culture, where things are usually dealt with as needed, when they come up, instead of planned for with what-if scenarios?

Planning Ahead vs. Just-in-Time. What is the value your culture places on planning, from an idea’s inception through execution to fruition? Is the culture considered methodical, where it is customary to plan ahead, with clearly defined steps of a process? Or is it a just-in-time culture, where things are usually dealt with as needed, when they come up, instead of planned for with what-if scenarios?

![]() Linear vs. Fluid Thinking. How are projects planned, problems solved, and critical components of a deliverable realized? Societies that place a heavy emphasis on tradition and order will follow the tried-and-true process, whereas societies that encourage the new will gravitate toward a more fluid approach that explores new ways of achieving results.

Linear vs. Fluid Thinking. How are projects planned, problems solved, and critical components of a deliverable realized? Societies that place a heavy emphasis on tradition and order will follow the tried-and-true process, whereas societies that encourage the new will gravitate toward a more fluid approach that explores new ways of achieving results.

![]() General vs. Detail. People with a general outlook bring a big-picture perspective to an entire process, while people with a detailed approach look at individual components and a situation’s specifics.

General vs. Detail. People with a general outlook bring a big-picture perspective to an entire process, while people with a detailed approach look at individual components and a situation’s specifics.

Figure 7-3. Five cultural clusters and their components.

Within each cluster (column 1), which component (column 2) is currently your team’s biggest challenge (column 3)? What actions or further steps can you take in this world of diminished cues (column 4)?

Five Effective Strategies for Cross-Cultural Interactions

You can L E A R N to improve your daily interactions by incorporating the strategies behind this acronym into your CCC.

Listen

Effectively Communicate

Avoid Ambiguity

Respect Differences

No Judgment

Strategy 1: Listen

Active listening is the single most useful way to overcome barriers to effective communication. We listen for meaning by checking back with the speaker to ensure that we have accurately heard and understood what was said. Communicating across cultures adds another layer to the “noise” that is present, which makes it critical to add that extra step of checking back. Active listening is the key to avoiding misinterpretations. For example, people from different cultures may use the same word in different ways (as we’ve already seen), so repeating what you think you heard and asking if that’s what the speaker intended confirms your understanding of the word’s meaning.

Learn to get beyond the distractions that may interfere with properly hearing your speaker, such as accents, limited vocabulary, and lack of nuance or thorough understanding of a language. Be attuned to the speaker’s cultural background and communication style.

Beyond active listening, you can tone down your language, avoiding harsh and/or difficult words as well as adjusting the timing and speed of your speech. Incorporate the following techniques into your everyday communication:

![]() Listen without considering what you will say next. Take the time to listen rather than try to guess what’s being said. Avoid thinking ahead.

Listen without considering what you will say next. Take the time to listen rather than try to guess what’s being said. Avoid thinking ahead.

![]() Ask questions to ensure that you accurately understand the message being conveyed.

Ask questions to ensure that you accurately understand the message being conveyed.

![]() Paraphrase back to the speaker to clarify understanding.

Paraphrase back to the speaker to clarify understanding.

![]() Avoid multitasking when listening to virtual team members.

Avoid multitasking when listening to virtual team members.

![]() Consider the speaker’s background when evaluating the message, and be aware of and suspend assumptions based on your own cultural interpretations.

Consider the speaker’s background when evaluating the message, and be aware of and suspend assumptions based on your own cultural interpretations.

![]() Use a headset if possible, to keep your hands free so that you can take notes to verify the important points of the conversation and the action items that need attention with your colleagues.

Use a headset if possible, to keep your hands free so that you can take notes to verify the important points of the conversation and the action items that need attention with your colleagues.

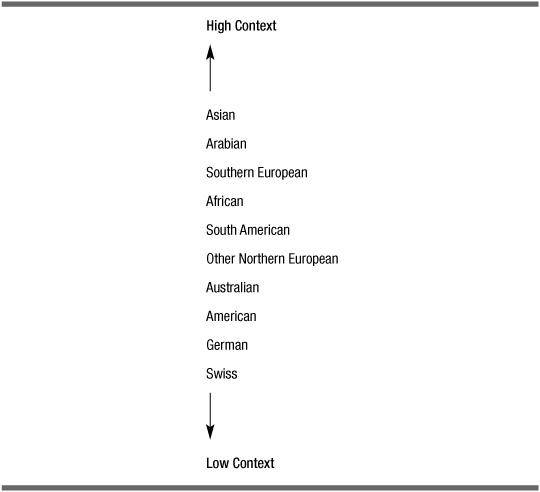

Strategy 2: Effectively Communicate

Aim to keep the communication lines open and transparent so that when conflicts arise—and they will—a resolution is found quickly. Here is a helpful four-step technique to keep the cultural communication lines open:

1. Respond with appropriate words that will not inflame a situation, when you sense difficulty.

2. Deliver balanced feedback.

3. Build on an idea.

4. Give credit/positive reinforcement.

For examples of situations when you might use each of the four techniques and what to say, see Figure 7-4.

Since virtual teams rely heavily on voice communications, they need to compensate for the lack of visual cues. Regarding teleconferences, here are some good practices to follow:

![]() If the conversation appears to be coming to a close, conclude with a transition or sum-up statement. For example, “So you are saying that …”

If the conversation appears to be coming to a close, conclude with a transition or sum-up statement. For example, “So you are saying that …”

![]() Allow the other person to complete his thoughts. Avoid dominating the conversation, even if you feel you have a lot to say.

Allow the other person to complete his thoughts. Avoid dominating the conversation, even if you feel you have a lot to say.

![]() If the other person sounds bored and uninterested, change the subject and/or direction of the conversation. Keep the other person involved by asking questions, and even asking where the person would like the conversation to go.

If the other person sounds bored and uninterested, change the subject and/or direction of the conversation. Keep the other person involved by asking questions, and even asking where the person would like the conversation to go.

Figure 7-4. CCC technique: respond, give feedback, improve ideas, give credit.

Strategy 3: Avoid Ambiguity

Awareness of culturally derived differences in behavior and communication decreases ambiguity. The ability to avoid ambiguity is directly tied to active listening skills. Avoiding or tolerating ambiguity doesn’t necessarily mean that you deliberately avoid these types of situations. You want to be able to react to new, different, and potentially unpredictable situations, but you also want to avoid the uneasiness in such situations that can lead to frustration and hinder your ability to communicate. The greater your knowledge about another culture the less ambiguous it becomes, and when someone behaves accordingly you won’t be surprised and uncertain.

These suggestions can help build a virtual environment that avoids ambiguity:

![]() Create a safe, friendly environment that encourages participation.

Create a safe, friendly environment that encourages participation.

![]() Share information about team members’ cultural backgrounds.

Share information about team members’ cultural backgrounds.

![]() Be careful with humor. It can be easily misunderstood, or even considered offensive in many cultures. In most cases, it is best to just avoid making jokes.

Be careful with humor. It can be easily misunderstood, or even considered offensive in many cultures. In most cases, it is best to just avoid making jokes.

![]() Recognize your own assumptions and prejudgments, which may be clouded by cultural backgrounds, past experiences, and a subconscious bias.

Recognize your own assumptions and prejudgments, which may be clouded by cultural backgrounds, past experiences, and a subconscious bias.

![]() Encourage participation in conference calls so that questions are brought up.

Encourage participation in conference calls so that questions are brought up.

![]() Build in feedback loops (e.g., asking questions, paraphrasing what someone says, asking someone to repeat a statement) to ensure clarity.

Build in feedback loops (e.g., asking questions, paraphrasing what someone says, asking someone to repeat a statement) to ensure clarity.

Strategy 4: Respect Differences

Effective CCC can be difficult if you have trouble showing respect for another person’s differences. Just as you want to be respected for different characteristics that you may bring to a group, others do as well. Attitude is everything, and you can encourage team members to think of their differences as the spice that lends interest to your Pepper Pot Soup.

While different cultures vary in how they show respect (e.g., the bow is customary in Japan), following these general rules should lead to positive results:

![]() Make it your business to learn at least one fact about every team member’s culture.

Make it your business to learn at least one fact about every team member’s culture.

![]() Acknowledge cultural differences and remind teammates to respect them.

Acknowledge cultural differences and remind teammates to respect them.

![]() Be professional; make it a point to assume a clear and welcoming tone when you communicate by phone.

Be professional; make it a point to assume a clear and welcoming tone when you communicate by phone.

![]() Be punctual when meeting someone new from an unfamiliar culture.

Be punctual when meeting someone new from an unfamiliar culture.

![]() Do not overgeneralize or attribute characteristics of a given culture to individuals; in other words, refrain from stereotyping, even when others around you do it.

Do not overgeneralize or attribute characteristics of a given culture to individuals; in other words, refrain from stereotyping, even when others around you do it.

![]() Use optimistic, positive terms in your written or oral communication.

Use optimistic, positive terms in your written or oral communication.

![]() Find every opportunity to acknowledge others.

Find every opportunity to acknowledge others.

![]() Demonstrate flexibility. Be open to discussing other options. If you find that you and the person with whom you are speaking want different things, try to find a middle ground and compromise. Being rigid and too tied to your way of doing things could set back your progress.

Demonstrate flexibility. Be open to discussing other options. If you find that you and the person with whom you are speaking want different things, try to find a middle ground and compromise. Being rigid and too tied to your way of doing things could set back your progress.

![]() Learn to use the words for “please” and “thank you” in the individual’s native tongue. Although no one expects you to master a slew of foreign languages, this simple gesture is appreciated.

Learn to use the words for “please” and “thank you” in the individual’s native tongue. Although no one expects you to master a slew of foreign languages, this simple gesture is appreciated.

![]() Watch or read the news from your team members’ countries of origin. Discuss cultural topics to better understand different viewpoints (although it may be best to avoid political issues).

Watch or read the news from your team members’ countries of origin. Discuss cultural topics to better understand different viewpoints (although it may be best to avoid political issues).

![]() Become aware of the traditional festivals of your virtual team members’ countries. They may genuinely appreciate an e-mail or IM greeting on those days.

Become aware of the traditional festivals of your virtual team members’ countries. They may genuinely appreciate an e-mail or IM greeting on those days.

![]() Use social networks to learn more about your virtual coworkers.

Use social networks to learn more about your virtual coworkers.

![]() Respect different time zones when scheduling virtual meetings. Work toward sharing this responsibility so that everyone’s availability and time preferences are honored equally.

Respect different time zones when scheduling virtual meetings. Work toward sharing this responsibility so that everyone’s availability and time preferences are honored equally.

Strategy 5: No Judgment

Respecting others means suspending judgment. Try this simple technique: Instead of jumping to conclusions consider that your cultural lens may distort the truth. Consider several alternative possibilities and use this three-part evaluation approach:

1. Describe (e.g., “Nat joins the call late every Monday”).

2. Interpret (e.g., “Nat doesn’t care about the job”).

3. Evaluate (e.g., “I’ll give Nat the less desirable projects”).

Now, consider the same evaluation approach with the addition of one more step in which you consider several options. This step is the one that many people skip, leading them to erroneous and often biased conclusions.

Describe. The situation that is causing concern is that “Nat joins the call late every Monday.” This time, before you make an assumption, consider several reasons for his tardy behavior. For example:

![]() He has familial obligations every Monday morning.

He has familial obligations every Monday morning.

![]() His start-of-week meeting with his boss always runs late.

His start-of-week meeting with his boss always runs late.

![]() He oversleeps after the weekend.

He oversleeps after the weekend.

![]() He doesn’t care about the job.

He doesn’t care about the job.

Interpret. Once you’ve formulated several hypotheses for Nat’s behavior, you are ready to make your interpretation. “Nat’s tardiness could be due to a factor that may be out of his control.”

Evaluate. “I will talk to Nat about his tardiness and learn more about why it’s happening.”

Additional Tips for Working Across Cultures

![]() Don’t assume that other people think/behave the way you do.

Don’t assume that other people think/behave the way you do.

![]() Accept the possibility that whatever occurred could be an anomaly caused by any number of circumstances (e.g., someone having a bad day or dealing with personal issues).

Accept the possibility that whatever occurred could be an anomaly caused by any number of circumstances (e.g., someone having a bad day or dealing with personal issues).

![]() Be aware of your personal biases (i.e., increase your self-awareness). Treat people as individuals and not as generalized stereotypes.

Be aware of your personal biases (i.e., increase your self-awareness). Treat people as individuals and not as generalized stereotypes.

![]() Remain positive. Don’t always assume the worst/negative outcome.

Remain positive. Don’t always assume the worst/negative outcome.

![]() Avoid blaming others.

Avoid blaming others.

![]() Take the time to reflect before saying/doing something that you may regret.

Take the time to reflect before saying/doing something that you may regret.

![]() Avoid making comments such as, “You don’t understand” or “What’s your problem?” These kinds of remarks may cause the other party to respond defensively.

Avoid making comments such as, “You don’t understand” or “What’s your problem?” These kinds of remarks may cause the other party to respond defensively.

![]() Use descriptive and nonevaluative language when communicating with others.

Use descriptive and nonevaluative language when communicating with others.

![]() Refrain from seeing things at the extremes (e.g., black/white, right/wrong) since there are many shades of gray.

Refrain from seeing things at the extremes (e.g., black/white, right/wrong) since there are many shades of gray.

![]() Be mindful of terms people use to explain themselves and the world around them, because certain terms have different meanings across cultures.

Be mindful of terms people use to explain themselves and the world around them, because certain terms have different meanings across cultures.

CASE STUDY

They Moved Me to … a Storage Room

As we near the end of this chapter I would like to share one last client story. Brigit was a British national (transferred to Japan) who managed a joint U.K.–Japanese project. The team was charged with building an interface for a large customer database. Brigit’s boss appreciated her probing style, which usually got right to the heart of an issue. When deadlines started to slip she made him, as well as her Japanese team members, aware of the situation and shared key points with all. Although her boss appreciated this honest assessment her Japanese colleagues did not share his point of view. They were embarrassed because she violated their norms for 1) showing respect to someone at a more senior level and 2) uncovering and discussing problems.

“They moved me to an office that was in reality a storage room,” she told me. “There I was, far removed from the people and information that I needed to keep tabs on how the project was going. My colleagues only spoke to me when I was absolutely needed. It was clear to me that in Japan coworkers keep their opinions to themselves. They don’t question authority, they just want to work in a harmonious place. They probably would have responded better if I had pointed out the problems indirectly. I should have said, ‘What would happen if shipping charges would not calculate properly?’ even though this was exactly what was happening and I knew that it was.”

When I was hired to coach Brigit she told me flat out that “perception is reality” and said that she understood that only she could repair her reputation. Thoughtful and highly motivated to develop better work relationships, she used the L E A R N strategies with her team. When the project ended, several Japanese colleagues surprised her with a lavish good-bye banquet before she returned to London—a true testament to what anyone can achieve by focusing on these commonsense tools.

Driving Along the Cross-Cultural Highway

In this chapter, you read comments by virtual managers who have earned their global driver’s license. Today, even if you manage locally, you deal with multicultural elements and work across diverse CCC styles. To work effectively in this environment you need to understand people if you hope to influence and motivate them to achieve business results. You need to become a manager of cultures.

Whether local or global, look at the landscape beyond the horizon, recognizing that events at one location impact another. I call this type of visionary leadership Vista-Leadership (more about this concept in Chapter 8). It requires advanced understanding, visioning, and extreme openness to how people interact in different cultures. As so beautifully put by a client who led a global team at a health care solutions company, “When it comes to becoming a manager of cultures, you need to know that you don’t know. There are so many unknowns and you have to manage and look for them; people don’t speak exactly what they mean. They maintain distance, and when you are a global manager who is not from their [location], you need to understand them.”

To gain clarity on your team’s cross-cultural interactions, reflect once again on the five Cultural Clusters. Use them to assess your team members, and then complete the Virtual Roadmap exercise at the end of the chapter. It is designed to help you integrate the L E A R N strategies that will best address the specific challenges within your team, as well as further expand your team’s thinking about cross-cultural communication, adaptation, and integration.