CHAPTER 3

Context Communication: Definitions and Challenges

Effective communication is the first of the four elements of successful virtual team performance. When interacting with others, the more we can communicate our context, the greater the connection and, therefore, the greater the chance of achieving the objectives that we set out to accomplish.

The virtual workplace has transformed the business landscape across the globe in many positive ways, but it has also altered the essence of the human connection. As you know firsthand, connections that occur during face-to-face exchanges become more elusive when we lose close proximity with others.

Why is it important to foster the human connection in the virtual world? It seems obvious that when team members share a bond they work more productively. In the long run, building good relationships enables more effective team performance and reduces situations that are dominated by conflict. These key benefits directly impact work product and the organization’s key deliverables.

The human connection also allows a richer path of information exchange through what I call Context Communication. This allows virtual team members to understand the setting that their teammates are working in and to find the best approach to collaboration. When context is missing, virtual teams are forced to make a greater effort to maintain the human connection, which in turn leads to new behaviors and ways of communicating.

Let’s look at two different scenarios to gain an understanding of how the multiple layers of Context Communication work and their important implications for teamwork.

Scenario A: On-Site Maria

Meet Maria, a Boston-based software consultant who works at Results Software Ltd., a firm specializing in enterprise media solutions. These days she spends much of her time running to and from meetings with her largest client, Xingo Media, an e-business publisher that develops databases for the industrial marketplace. A quick glance at her workspace shows a desk piled with paperwork (in spite of a laptop and second computer screen) and a phone that continually rings. Today is the final deadline for the deployment of Xingo’s e-collaboration website, a multistage project that Maria has worked the past year to complete. Unfortunately, technical issues arise at the last minute and Maria finds herself putting out fires, tracking down their causes, and locating knowledgeable experts to fix these last-minute problems.

You know Maria because both of you have worked at Results Software headquarters in Boston for almost five years, sometimes collaborating on the same projects because she is the point person on XLB Standards. Today, at 10:00 a.m. EST, you sent her an e-mail about the launch of XLB in several satellite offices of your client, Sea-Stars Media. You need her input for tomorrow’s meeting with Sea-Star’s senior executives about the rollout. As she runs past you in the hallway, Maria looks stressed out. She’s deep in conversation on her hands-free phone, with hot coffee in one hand, an overstuffed file in the other. Hopefully, she won’t spill the coffee as she goes about her business. There’s worry in her voice and you can’t help but feel concerned about her deadlines.

You know from hallway chats and from the general atmosphere in the office about the demands of the Xingo Media project. Although it does not directly affect you, almost every department at Results has been involved in it at some point. Maria’s promotion is dependent on the successful completion of Xingo, and you are excited that all her hard work will finally pay off. You want to find the best approach to getting Maria’s timely input without distracting her from an important deadline. She walks into her office at 4:45 p.m., and you know this is her last opportunity to catch up at her desk because she always leaves at 5:00 p.m. sharp to pick up her nine-year-old twin sons from the local after-school program that ends at 5:30 p.m. Displayed throughout her office are family photos of her sons at various ages; you have met the boys and are aware of her daily routine.

If you didn’t know Maria’s situation so well, you might be worried about the lack of response to your e-mail; instead, you know that Maria diligently logs in remotely from home to catch up on e-mail once her children are settled after 7:00 p.m., so you are not concerned. You know she is committed to Results Software, works hard, takes on a large workload, but can always be relied on to help her teammates. Therefore, her 7:15 p.m. e-mail stating that your request will be ready by 9:30 a.m. tomorrow is no surprise.

Result: Because of your observations and background knowledge, you are not surprised that you didn’t receive Maria’s status update to your 10:00 a.m. e-mail until 7:15 p.m. that day, despite its “urgent” status. In fact, you could have predicted this outcome when you sent your e-mail.

Now let’s look at this same situation from another vantage point—minus the visual cues, background information, personal history, shared lingo, and common understanding that you and Maria have.

Scenario B: Virtual Maria

You are a consultant with Results Software Ltd., working in the San Francisco office, so you have neither met nor spoken with Maria, who also has five years’ tenure with the company. You are working on the launch of XLB for Sea-Stars Media in several of its satellite offices and were told to contact Maria today by a colleague who recommended her as the company expert on XLB Standards. So, this morning, at 10:00 a.m. EST, you e-mailed her about the launch, stating that you need her response for tomorrow’s meeting with senior executives about the rollout. Because this simple request was urgent, you expected Maria to complete it within fifteen minutes. You sent your request by 7:00 a.m. PST, to make sure it was on Maria’s radar early that morning on the East Coast. By noon EST, you place a follow-up call about the e-mail. No answer. You leave a voice mail hoping that she will return the call today. By 4:00 p.m. EST, you question if Maria is still with Results Software. If she is, you wonder if perhaps an emergency arose that prevented her from responding to your request.

It is now 5:00 p.m. EST, the end of your business day, and she never answered your e-mail. Regrettably, you conclude that she will not do so today and decide on a backup plan. You do not assume that she will work beyond standard business hours.

Result: At 7:15 p.m. EST, Maria responds to your e-mail. However, by this time you dropped other work commitments and skipped a run-through of tomorrow’s meeting in order to spend two hours working on a backup plan. Now, you have to discard the extra work you did and are perplexed by Maria’s last-minute but welcome expertise.

The Difference?

What was the difference between scenario A and scenario B? Did Maria do anything differently? What do you know about Maria and her situation in scenario A that was not verbally communicated? Do you have the same information in scenario B? What happened because of this lack of information? What does XLB mean? Without context information you may not know what this acronym represents. If you were not familiar with Maria’s personal life, what assumptions might you make when she does not respond during the business day? Without knowing her circumstances you might attribute her silence to a poor work ethic. Did she stay home—and if so, why didn’t she check e-mails from there? Is she at her office? Is she even in this country or time zone? Is her phone working? Is she a responsible employee committed to the company? Is she competent, or simply overwhelmed? Who is Maria?

Scenario A presents a deep reservoir of background information about Maria, including her family, workload issues, schedule, work habits, personal characteristics, career goals, and hot spots in her current workday. You know her moods, concerns, caffeine levels, and more. That is a lot of information, and it helps you understand how to maintain a good working relationship. When you are aware of the other projects a team member juggles along with yours and can observe that person running to and from meetings, you are able to gauge the timing of a response. With background information it is easier to predict behavior, manage your own expectations, choose the best approach, and in general, maintain a good working relationship.

The main difference between scenario A and scenario B is Context Communication. In the first scenario, you know the many reasons Maria has not responded. Context had been communicated not through words, but through visual cues and shared history. Without being explicitly told, you knew when to expect a response from Maria.

What Is Context Communication?

As you can see from Maria’s example, there are many different types of cues that provide information, and these layers of observable cues create context, or a sense of place. Context Communication is the framework within which we connect the dots so that they make sense. Working in the same office as our teammates allows us to observe behaviors, actions, and surroundings, creating background information from which we infer a heightened understanding of their situation. Simply put, a shared context for understanding is a given for on-site teams, and no effort is required to connect the dots because when you can see, hear, and sense cues, the dots connect themselves.

Context Communication means that team members working in close proximity can quickly assess the cues and therefore understand the context in which certain behaviors take place. Observations about another person’s verbal tone, body language, and other visual cues create the context that helps us understand each other, the task at hand, and the overall work situation. Informal hallway or watercooler chats that are common with on-site teams provide a natural way to conduct casual conversations, build personal relationships, and learn additional context, some of which you store in the back of your mind for future situations.

Context Communication is achieved in three ways:

1. Environmental Cues. Visual, audio, and physical cues provide information about your physical surroundings, your schedule, and your workload.

2. The Medium. The format used for communication, such as e-mail, voice, videoconferencing, or face-to-face interactions, determines the richness of information that is communicated.

3. Relationships. Knowledge of teammates’ personalities, career goals, friendships, alliances, and moods provides cues about work behaviors.

Let’s break down the rich, multilayered information about Maria that was available in scenario A into the three types of Context Communication.

Environmental Cues

The first type of Context Communication eroded in a virtual setting is environment. The most immediate cues lost are those we take for granted in a shared office environment, such as the physical condition of the workspace, as well as visual and audio cues we get from having people around us. Context Communication cues diminish with distance, and I refer to them as diminished cues of the virtual environment. Virtual coworkers don’t know if you are sitting at your desk, attending a meeting, or away for a particular reason. They can’t see Maria running between meetings. They can’t hear the phone ringing or overhear hallway chatter such as, “Did you hear about the Xingo deadline today?” When on the phone with a virtual teammate, it is not possible to know if she is doing something else, such as typing an e-mail or texting. Imagine if you couldn’t hear Maria’s phone continually ring (the implication being that there are many demands for her time). Imagine not knowing that a phone call might not be the best way to reach her. Unless Maria has communicated the context of her busy day, which is filled with meetings away from the office, and that she usually isn’t available by phone, you may be at a loss.

There are limits to the available information about team members in the virtual space. These limits point to the three challenges faced by virtual teams due to the constraints of environmental Context Communication.

Environmental Challenge 1: Team Members’ Awareness of Tasks and Availability

The on-site scenario provided evidence of Maria’s busy schedule. An empty office indicated that she was at a meeting and probably couldn’t call or e-mail immediately. You saw stacks of papers at her workstation, which implied a busy workday. You heard her on the phone and could see that she placed someone on hold. With so much going on you might conclude that calling might not be the best way to engage her. Next, she raced past you, indicating that she was pressed for time. Later, she returned to her office—but you knew that didn’t mean she was available. At that point, you already had enough information to assess the situation, but the cues kept adding to your understanding. Certainly you conclude that Maria is not slacking off.

In addition to visual cues, you knew from past conversations that Maria spent an entire year working on a large project that was due today. You may have overheard conversations about this key project in the hallway or chatted with coworkers at lunch. Lastly, the company’s intranet includes a calendar listing every current project by consultant and deadline, which is continually updated and accessed by everyone. As you can see, there are many sources of information in a nonvirtual workplace that provide rich information about Maria.

The shared calendar is more important virtually than in the on-site world because it becomes one of your few sources of context to learn about Maria’s availability. However, even this calendar does not indicate interruptions and unplanned situations. Unless virtual Maria explicitly tells you about the endless stream of interruptions, you would not infer it from her calendar. Nor would you know if virtual Maria had spilled her coffee on her expensive suit and had to go to the dry cleaners next door to avoid ruining it.

Here are some practical tips to help you communicate context around tasks and availability challenges:

![]() Use group discussions and shared documents to facilitate awareness of team members’ additional projects, tasks, and workload. You can add information about a team member while discussing a project. For example, you may add something like “Jason has been swamped with ABC project, so you might have to get your request in early.”

Use group discussions and shared documents to facilitate awareness of team members’ additional projects, tasks, and workload. You can add information about a team member while discussing a project. For example, you may add something like “Jason has been swamped with ABC project, so you might have to get your request in early.”

![]() Share meeting calendars with teammates and keep the calendar up-to-date, even with last-minute additions.

Share meeting calendars with teammates and keep the calendar up-to-date, even with last-minute additions.

![]() E-mail the team (and other stakeholders) if an unexpected situation makes you unavailable. You can also create standard procedures for planned situations, such as vacations, notifications, or extended trips, as well as for emergencies, to enable team members to communicate schedules and unforeseen interruptions (personal or work-related) within minutes.

E-mail the team (and other stakeholders) if an unexpected situation makes you unavailable. You can also create standard procedures for planned situations, such as vacations, notifications, or extended trips, as well as for emergencies, to enable team members to communicate schedules and unforeseen interruptions (personal or work-related) within minutes.

![]() Ensure everyone briefly comments on what is going on in their world via a round-robin at the beginning of meetings. Giving colleagues an opportunity to talk about their issues is one way to create a habit of communicating context.

Ensure everyone briefly comments on what is going on in their world via a round-robin at the beginning of meetings. Giving colleagues an opportunity to talk about their issues is one way to create a habit of communicating context.

![]() Model the behavior that you want to see in others. Share social and personal information, with a rich exchange about your context, and encourage others to do the same.

Model the behavior that you want to see in others. Share social and personal information, with a rich exchange about your context, and encourage others to do the same.

Environmental Challenge 2: Lost Riders

How can you tell if someone is really working? When a team member continually pushes back deadlines, how would you know if the reasons are valid? How long does it take to detect if someone is not fulfilling her responsibilities in a virtual environment? What do you do if someone stops responding to your e-mails and phone calls, and you cannot stop by her desk? Is this team member lost, missing, or just avoiding you?

Many clients tell me that the virtual environment makes it easier for team members to hide. Some people may take advantage of the lack of daily oversight; they may get “lost” or go missing. The first clue is that deadlines are continually pushed back, and then deliverables aren’t produced for days, weeks, or months. The critical time to notice situations that could lead to potential issues is during the early phase of a new project or when a new member joins the team. Also, by keeping time lines for deliverables short in the early phases, it is easier to catch problems. In fact, some clients find that short time lines work best throughout the entire life cycle of the project.

Identifying Lost Riders

![]() The individual often pushes back on deadlines, and you lack the information to verify the validity of the push-back.

The individual often pushes back on deadlines, and you lack the information to verify the validity of the push-back.

![]() There’s a time lag in response to e-mails and phone calls.

There’s a time lag in response to e-mails and phone calls.

![]() The team member doesn’t contribute work product or update reports although claims to be in meetings or on the phone most of the day working on your project.

The team member doesn’t contribute work product or update reports although claims to be in meetings or on the phone most of the day working on your project.

![]() In extreme cases, a team member has seemingly stopped responding to requests.

In extreme cases, a team member has seemingly stopped responding to requests.

Tips for Handling Lost Riders

![]() Have short-term goals and deliverables so that you can identify issues early.

Have short-term goals and deliverables so that you can identify issues early.

![]() Bring issues to light as soon as you discover them. Discuss them with the team members involved.

Bring issues to light as soon as you discover them. Discuss them with the team members involved.

![]() Come up with techniques to deal with people who are not responding. You can prevent this behavior by creating team Rules of the Road during the Team Setup stage, as discussed in Chapter 2. If team rules are violated, colleagues can bring up these issues as soon as they occur.

Come up with techniques to deal with people who are not responding. You can prevent this behavior by creating team Rules of the Road during the Team Setup stage, as discussed in Chapter 2. If team rules are violated, colleagues can bring up these issues as soon as they occur.

![]() Develop availability standards. Have team members state their working hours and inform others how often they check their voice mail, e-mail, and interoffice mail. And establish a standard for how quickly to respond to each mode of communication. You can publish availability standards on the team’s website or in a shared system. An added advantage of availability standards is that they act as a foundation for establishing trust.

Develop availability standards. Have team members state their working hours and inform others how often they check their voice mail, e-mail, and interoffice mail. And establish a standard for how quickly to respond to each mode of communication. You can publish availability standards on the team’s website or in a shared system. An added advantage of availability standards is that they act as a foundation for establishing trust.

![]() Have a clear performance plan, including escalation measures, for the team. Follow through when someone becomes unresponsive or unproductive.

Have a clear performance plan, including escalation measures, for the team. Follow through when someone becomes unresponsive or unproductive.

Be careful in labeling someone a Lost Rider. Just because someone doesn’t speak up during conference calls doesn’t mean she is a Lost Rider. Keep in mind that personality, hidden conflict differences, expectations about the agenda or call procedures, or cross-cultural differences are all factors that may prevent a team member from speaking up.

Environmental Challenge 3: Multitasking

One of the biggest complaints I hear regularly involves people multitasking and not truly listening. In many ways, this is the new “normal” in the business world. People often work on more than one task while conducting business calls. I met one manager who told me, “When you are in a conference room, you can see what people are doing and know if they stay engaged. On a virtual team, everyone is doing several things at once. I was expecting communication to be smoother and better understood, but I now realize that not everyone was fully participating.”

Her comment made me consider the value of multitasking in the virtual environment. People appear to be listening during calls, but are they? Despite various data tools that capture caller activity during the virtual interaction, how can you tell if your virtual teammates are really listening?

Without physical (environmental) context, you can’t see if your teammates are concentrating. When team members are overworked and short on time, they may feel freer to perform other tasks, like responding to e-mails, while participating on a group call. Nowadays, some online tools enable managers to see if someone is clicking on other screens or staying with the screen under discussion. The level of engagement can now be measured, and I’ve talked to several managers who can determine the percentage of team members actively engaged during a call. Many interviews conducted for this book noted that (1) teammates often multitask and (2) virtual managers find this behavior frustrating.

Identifying Excessive Multitasking

![]() The team member sounds preoccupied or has a delayed response while on a conference call.

The team member sounds preoccupied or has a delayed response while on a conference call.

![]() Background sounds are audible, which may result from keystrokes, driving in a car, or running an errand while discussing a project.

Background sounds are audible, which may result from keystrokes, driving in a car, or running an errand while discussing a project.

![]() The team member seems distracted, lost in the flow of the conversation, or asks you to repeat yourself several times. This could mean that he “checked out” of the meeting or has a bad phone connection. It could also denote cross-cultural issues, with that individual having difficulty understanding your words.

The team member seems distracted, lost in the flow of the conversation, or asks you to repeat yourself several times. This could mean that he “checked out” of the meeting or has a bad phone connection. It could also denote cross-cultural issues, with that individual having difficulty understanding your words.

![]() You notice an e-mail sent from a fellow participant during a phone conference; however, that means that you too are multitasking!

You notice an e-mail sent from a fellow participant during a phone conference; however, that means that you too are multitasking!

Tips for Avoiding Excessive Multitasking

![]() Set priorities around your team objectives to help people focus on the two or three main ones.

Set priorities around your team objectives to help people focus on the two or three main ones.

![]() Write a Team Code that details acceptable behaviors associated with multitasking, such as:

Write a Team Code that details acceptable behaviors associated with multitasking, such as:

• Running errands during work hours.

• Turning off cell phone ringer/buzzer, e-mail notification, and MP3 players and tuning in during calls.

• Confronting or reminding team members who excessively multitask.

• Agreeing on when to use the “mute” button during phone conferences.

• Agreeing that certain multitasking behavior is acceptable, provided that it is done within reason. One virtual manager working for a semiconductor chip company agreed with her team that during long meetings people could work on their laptops while listening. They were not forced to participate unless something was relevant to their part of the project.

![]() Realize that multitasking is common in the virtual environment and help team members to prioritize and become fully present while on your calls by creating more urgency around deliverables.

Realize that multitasking is common in the virtual environment and help team members to prioritize and become fully present while on your calls by creating more urgency around deliverables.

![]() Ensure that a communication system exists to alert everyone when certain team members are participating in a scheduled conference call and therefore are unavailable to quickly respond to e-mails.

Ensure that a communication system exists to alert everyone when certain team members are participating in a scheduled conference call and therefore are unavailable to quickly respond to e-mails.

![]() Check in with teammates regularly by asking questions; for example, “How is it going on project X?” Also, get them involved in the dialogue during the call.

Check in with teammates regularly by asking questions; for example, “How is it going on project X?” Also, get them involved in the dialogue during the call.

![]() Focus on adding value rather than adding volume. Identify activities that will truly add value to what is important and do them.

Focus on adding value rather than adding volume. Identify activities that will truly add value to what is important and do them.

![]() Pay attention to what you can get done now.

Pay attention to what you can get done now.

The Medium

Medium is the second type of Context Communication; it is the format used to communicate with virtual members. Medium determines the richness of information that is received, with e-mail, phone, and videoconference the most common means of communication. But there are other ways for virtual workers to communicate, too, including using instant messaging and chat programs, whiteboards, discussion boards, file sharing, web sharing, text messages on mobile devices, and social media websites. Should you type an e-mail or send an IM? Leave a voice mail or call back? Is a videoconference better for the topic at hand? Is it better to comment on your colleague’s social media site or on his blog? For a particular situation how you answer these questions will determine what you communicate and the type of response you might get.

Using Technology to Communicate

Today’s technology-based contact systems offer speed and convenience as well as the ability to instantaneously communicate to large numbers of people over large distances. However, technology-based communications will always be bound by our senses, which rely upon the traditional forms of communication.

Imagine that your request to Maria about the XLB launch for Sea-Stars Media was stated in several highly detailed paragraphs. Compare that with a short, targeted e-mail with details summarized in one paragraph. Which message would better achieve your results? Although you may decide on a brief e-mail, you do not know if Maria’s in-box is flooded with hundreds of messages, nor are you privy to her e-mail filters or know what keywords in the subject field would attract her immediate attention.

A variety of technological media is available to you: e-mail, text and voice messaging, electronic message boards, chat rooms, telephone conferencing, videoconferencing, and virtual file sharing. Technology is changing so rapidly that undoubtedly newer options will appear within a short time. Here, I want to review and provide practical tips for the three most popular forms of communication: written, voice, and “virtual in person.”

Written Communication (E-Mail)

Electronic messaging—which includes e-mail, short message service (SMS) text, and instant messaging (IM)—is the most common virtual communication tool, but it tends to be very linear (one way) and stripped of all but the most important details. I am often amazed at how many e-mails people receive on a daily basis. People send e-mails across the cubicle or across the hall instead of walking over and having a personal interaction with their coworkers. Messages are often misunderstood and “cc:” (carbon copy) messages, in particular, become part of e-mail wars that can be defused by a simple conversation. Sometimes cleaning your in-box becomes another time-consuming task.

With technology we can do more things at once, and faster, than before, but our expectations have also expanded to meet this increased capacity. When someone sends an e-mail or text message, the expectation is an immediate response. E-mail is a double-edged sword. Although it enables easy connection, it creates human disconnection. How often do you e-mail a coworker instead of walking over to his desk or picking up the phone?

E-mail is appropriate for certain types of short updates and information sharing, such as progress reports, logistical updates, and project planning. But linear modes cannot communicate the rich contextual information that is the hallmark of same-time/same-place team interactions, like those afforded by conversing in a coworker’s office or attending a live, in-person meeting.

Manage Your E-Mails or They Will Manage You! Despite potential issues with e-mail, it is universally recognized as an essential tool that is fast, efficient, and a major factor in driving the virtual workplace as a viable work arrangement. E-mail helps team members stay connected and informed, replacing snail mail for countless nuggets of information that used to be sent via letter. Information that not too long ago reached its destination in days can now be received in a fraction of a second, anytime, anyplace. However, the downside is that access to instantaneous information can cause data overload and frustration. Therefore, finding ways to manage e-mail is vital.

One option is having your team come up with e-mail filtering rules as part of your Team Code for handling messages. A sample protocol is shown in Figure 3-1.

Once the appropriate protocol is in place, consider what goes into writing an effective e-mail. The real secret is to put yourself in the place of the person receiving the message. Many writers strive to make their message as actionable as possible but fail to follow some basic principles. Based on my experience training teams to write business communications effectively, I firmly believe in the five Cs of writing: concise, complete, concrete, compact, and clear. When you construct your e-mails, keep them in mind.

Figure 3-1. Team Code sample: e-mail protocols.

Concise. Keep your e-mails short. Omit unnecessary words and avoid repetitive phrases. Especially when working with colleagues across cultures, simplify words or redundant expressions.

Complete. Your e-mails should answer essential questions: who, what, when, and if appropriate where, why, and how. By answering these questions, you can ensure that your documents satisfy the second criterion of good business writing: completeness. Complete business communications are also well organized.

Concrete. Make your writing specific, free of jargon or clichés, and use the active voice. In active voice, the person taking action appears first in the sentence and word order is more direct. For example, “I reviewed Arlene’s synopsis of the marketing plan,” rather than “The marketing plan that Arlene created a synopsis for was reviewed.”

Compact. Limit your e-mail to short paragraphs consisting of sentences related to a single topic; keep them brief and use common words that are easy to grasp. When presenting several ideas, list items in bullet points, leaving space between paragraphs so that readers can follow your ideas.

Clear. Unlike a phone or face-to-face conversation, where people send and receive verbal and nonverbal feedback, written communication can be more problematic. Consider the following: First, you don’t always receive feedback about how your e-mail is being interpreted. It is therefore possible for the reader to misinterpret what you have written and mistakenly believe that he has understood your intent. Second, once you hit “send” the message is gone and cannot be pulled back. To avoid these problems with sensitive information, write your e-mail and then wait a bit before rereading the message; put yourself in your reader’s shoes before clicking “send.”

Tips for Writing Effective E-Mails

![]() E-mail is subject based, so use a direct subject line that is simple, helps your reader prioritize the message, and is easy to retrieve. If the subject of your e-mail has changed, update the subject line to reflect that change.

E-mail is subject based, so use a direct subject line that is simple, helps your reader prioritize the message, and is easy to retrieve. If the subject of your e-mail has changed, update the subject line to reflect that change.

![]() Designate priority, such as “Response Requested” or “FYI no decision required.”

Designate priority, such as “Response Requested” or “FYI no decision required.”

![]() Keep your message short and use bullets, since people increasingly receive messages on the go, on their smartphones or other mobile devices.

Keep your message short and use bullets, since people increasingly receive messages on the go, on their smartphones or other mobile devices.

![]() Consider a “no scrolling” rule; that is, only include as much information as the individual can see in one screen without having to scroll down. This will force you to keep your message clear and succinct.

Consider a “no scrolling” rule; that is, only include as much information as the individual can see in one screen without having to scroll down. This will force you to keep your message clear and succinct.

![]() Use headers and numbers, particularly when asking the recipient to respond to action items.

Use headers and numbers, particularly when asking the recipient to respond to action items.

![]() Avoid writing in all capital letters unless it is an acronym; some people may interpret capital letters as yelling.

Avoid writing in all capital letters unless it is an acronym; some people may interpret capital letters as yelling.

![]() Avoid making jokes or using sarcasm since this might be offensive or easily misunderstood.

Avoid making jokes or using sarcasm since this might be offensive or easily misunderstood.

![]() Update your group lists; when you receive an e-mail message as part of a group, be sure to consider whether your reply should be sent to all recipients.

Update your group lists; when you receive an e-mail message as part of a group, be sure to consider whether your reply should be sent to all recipients.

![]() Don’t waste people’s time by copying them on everything to cover your back. If it is important to copy the person, then do it. But be aware that people can read the wrong meaning into your words and are busy themselves. Ask yourself, “Who else needs to know about this? Is it really necessary to copy them?” The answer to this question will determine if a “cc:” is needed.

Don’t waste people’s time by copying them on everything to cover your back. If it is important to copy the person, then do it. But be aware that people can read the wrong meaning into your words and are busy themselves. Ask yourself, “Who else needs to know about this? Is it really necessary to copy them?” The answer to this question will determine if a “cc:” is needed.

![]() When forwarding an e-mail, briefly state the purpose and action required.

When forwarding an e-mail, briefly state the purpose and action required.

![]() Carefully review your message before you send it to check for and to correct potential misinterpretations.

Carefully review your message before you send it to check for and to correct potential misinterpretations.

![]() Start with “hello,” not “good morning” or “good afternoon”; you won’t know when the message will be read, especially for teams that follow the sun and communicate mostly by e-mail.

Start with “hello,” not “good morning” or “good afternoon”; you won’t know when the message will be read, especially for teams that follow the sun and communicate mostly by e-mail.

![]() Follow up complex e-mails with phone conversations to verify that your recipient understood the subtleties of your message. Or, have the conversation first, and then send an e-mail to confirm the conversation afterward.

Follow up complex e-mails with phone conversations to verify that your recipient understood the subtleties of your message. Or, have the conversation first, and then send an e-mail to confirm the conversation afterward.

Written communication requires extra care because virtual teams don’t have watercooler interactions to patch things over. Before interpreting something negatively or escalating it, give the person the benefit of the doubt, and refrain from sending an angry e-mail immediately.

As a general guide you want to be extra sensitive when sending e-mails to colleagues who work remotely. A good rule of thumb: When in doubt, pick up the phone. And, if you are on the receiving end of a puzzling or troubling e-mail, call your colleague. If you feel irritated, take a deep breath and then dial the number. A short call can save hours of wasted time in writing e-mails about issues that are better conveyed in telephone conversations.

Voice Communication (Telephone)

Your voice is a powerful communication tool, and the telephone is a tried-and-true medium for “keeping in touch.” On the phone, you can express your thoughts with urgency and emotion in a way that an e-mail cannot convey. The live voice remains an indispensable tool for rich and accurate communication.

Since the telephone has become such a common part of daily life, one would think that we have mastered this medium. However, that is not the case. We sometimes take for granted the ease of a phone conversation, or view its use as a necessary evil. Many virtual teams spend a good part of the workday calling each other, sometimes connecting, more often than not, leaving a message.

Voice Mail. Voice mail has an important place in virtual communication since it has the advantage of conveying the sender’s tone, which adds an important dimension to Context Communication. There are specific situations where voice mail is particularly useful, such as:

![]() For giving status updates (either one-on-one or a group broadcast)

For giving status updates (either one-on-one or a group broadcast)

![]() To convey information that does not require a real-time conversation

To convey information that does not require a real-time conversation

![]() When the message is logical and brief

When the message is logical and brief

![]() When action items can be clearly stated and easily understood

When action items can be clearly stated and easily understood

Tips for Leaving a Voice Mail Message

![]() Keep the message structured, logical, and concise. The clearer it is, the greater the odds that the receiver will understand and respond to your message.

Keep the message structured, logical, and concise. The clearer it is, the greater the odds that the receiver will understand and respond to your message.

![]() Update your voice mail greeting frequently. State when you are available for a live chat, when you will return calls, and what number to call to reach a “real” person, if necessary.

Update your voice mail greeting frequently. State when you are available for a live chat, when you will return calls, and what number to call to reach a “real” person, if necessary.

![]() Speak clearly and slowly, especially when your teammates are from other countries.

Speak clearly and slowly, especially when your teammates are from other countries.

Virtual teams can also develop a Team Code for voice mail. Some managers set these expectations and post them for the team. Figure 3-2 is an example.

Figure 3-2. Team Code for voice mail.

Conference Calls. When it is necessary for teammates to interact in real time, the conference call serves as a “live” audio channel for the virtual team. It is the quickest and easiest way to discuss strategy, review key deliverables, or brainstorm options.

“I want to be 100 percent accessible and help my team members grow closer, because they can easily hide behind computers and not establish relationships. I take it upon myself to reach out to everyone and bring them along, learn from them, and incorporate their ideas. Each day we have the end-of-day conference call to connect, refine ideas, and plan for the next day’s events.”

—VICE PRESIDENT OF SALES, RETAIL COMPANY

This VP understands two important concepts about conference calls: First, his leadership and initiative drive the connection; and second, without that “people” connection, the team would not work as cohesively and therefore not as productively.

Many teams have a weekly/daily morning call. Others have calls at the end of each week or each day. Some conduct calls on a certain day while others rotate them by time zone. Whatever your virtual team does, I am sure you are on numerous conference calls each day. But are they effective? Most people don’t feel very positive about these calls and characterize them as frustrating experiences. They have been described to me as a “nightmare,” “pointless,” and “tedious.”

Here are ten practical suggestions to make your conference calls more productive:

1. Select a facilitator who can keep things moving. The conference call facilitator is not necessarily the leader, but could be. The key is to choose someone who is a skilled facilitator rather than a lecturer or manager. You want someone with skills in group dynamics and language, and who is able to construct relevant questions and remain sensitive to balancing work issues with participants’ time constraints. Consider having note-taker and timekeeper roles shared or rotated so that calls can be more efficient. And always start and end meetings on time so that people have fewer excuses to miss them.

2. Distribute the agenda beforehand. Treat the conference call as if it were a meeting. Prepare and distribute the agenda and any other documents pertinent to the meeting before the call takes place. Keep the group focused on the agenda and on the time.

3. Identify objectives up front. Ensure that participants are aware of the desired end results.

4. Have ground rules in place at the beginning. Set boundaries for everyone participating in the call by:

• Making sure that callers say hello and introduce themselves

• Saying your name each time you speak

• Using your mute button to eliminate background noise

• Focusing your comments and keeping them brief

5. Give feedback to participants. Tell them what they did well and where they need to shift focus. Do this halfway through if the call is not going well, or at the end if things ran smoothly.

6. Ensure that everyone is treated with respect. Your job as team leader and/or conference call facilitator is to protect the self-esteem of participants on the call. Facilitators should be objective, so don’t criticize anyone or allow anyone else to be attacked. In addition, do not let one person dominate or hog airtime. Keep track of who is actively participating, and engage silent individuals in the discussion.

7. Intervene if you believe discussions are running off-track. Nicely, but firmly, intervene if a participant is not following the ground rules. For example: “Thanks, Bart, for making that point. Let’s note it for later since it’s not part of today’s agenda.”

8. Maximize the entire group’s input. Be sure to get everyone involved. If you deem the call necessary and useful, make sure it is an interactive experience for everyone. Otherwise, ask yourself if the day’s business could just as easily be conducted in a series of e-mails.

9. Debrief at the end. Ask members whether they found the meeting valuable. Did it match your agenda and meet the intended outcomes? Conclude the call as you would any meeting, summarizing, confirming decisions, and reiterating future steps.

10. Evaluate before planning the next teleconference. Was every participant essential? Could the issues have been handled by e-mail? Was this precious time used to brainstorm, resolve differences, and make decisions? Make sure everyone’s time was well spent.

Conference Calls and Silent Riders. It is easy for team members to stay in the background and impassively witness a conversation in e-mail strings and conference calls. In the virtual workplace, a lack of contribution is less noticeable than at on-site meetings. Even motivated team members may be quiet during these times. I refer to colleagues who do not contribute during conference calls as Silent Riders. Silent Riders may fulfill their responsibilities but may need an extra push to join the discussion. To encourage quiet team members to speak up, you may need to try several approaches. Ask questions to keep the conversation alive. Or you can do a round-robin to hear from every attendee. Alternatively, you can occasionally ask a specific participant a question (“Alex, what do you think?”).

If you are dealing with global language barriers, Silent Riders may need an extra nudge. One of my clients, a virtual manager at an international insurance conglomerate, had to conduct regular conference calls with ten people from five different countries in Asia. During his first call, few team members spoke, and he found the added difficulties of language barriers and background noise made it even more difficult to communicate. Together we came up with these guidelines to draw out his Silent Riders.

1. Keep things simple (language, structure, process).

2. Send handouts ahead of time.

3. Conduct meetings with a high degree of facilitation.

4. Tightly structure the meeting, using one or more of the following techniques:

a. Set priority. Is the meeting high or low priority? Make sure you ask because participants may not speak up.

b. Ask people to talk about two things that are going well and two things that are not.

c. Practice “back briefing” by asking participants to paraphrase what they heard/understood.

d. Use a scale (like the Likert 1 to 5 scale) when framing questions to draw people out and get them to make decisions. For example, “Do you think XYZ is a 4 or 5?” That is, get people to say whether they agree or strongly agree with XYZ issue. Simple questions help Silent Riders speak up and stay involved in the discussion.

I like the saying “None of us is as smart as all of us.” Keep that saying in front of you as a reminder that the results of encouraging more reticent team members are worth the extra effort of engaging them. In addition, you cannot assume that every member on the call has all the relevant information, since the team is a fluid entity, with members leaving and arriving because of ongoing projects and commitments. Also, consider the kinds of questions that new team members participating in their first call might have. For instance:

![]() Were important points about the topic made on previous calls? (In other words, what is the history of an ongoing conversation?)

Were important points about the topic made on previous calls? (In other words, what is the history of an ongoing conversation?)

![]() What is this call supposed to accomplish?

What is this call supposed to accomplish?

![]() Who is responsible for specific agenda items and who is knowledgeable about key issues?

Who is responsible for specific agenda items and who is knowledgeable about key issues?

![]() Do I know what our team’s specific acronyms and shorthand mean?

Do I know what our team’s specific acronyms and shorthand mean?

Conference calls are indispensable for moving complex projects along. It is up to you, the manager, to create the context for meeting attendees to connect the dots to the bigger picture and drive your team success.

Virtual In-Person Communication (Video and Web Conferences)

It is commonly stated that when delivering a message, the impact on others is as follows: Voice accounts for 38 percent of the impact, and the actual message just 7 percent; however, visual impression delivers 55 percent of total impact. There is no substitute for eye contact. And of all mediums currently available in the virtual world, videoconferences most closely simulate live meetings. They enable participants to see one another, as if they are in the same room, which helps to foster relationships and mutual trust in the virtual space. Videoconferences can be used to introduce new team members. They are also highly useful when teams need to see a mechanical object in motion (e.g., how a prototype of a new product works), various package designs, or a sales presentation. Thanks to advances in technology, today’s video equipment produces high-quality images and is reliable and affordable. There are low-cost webcams that can easily be set up to record activity, as well as better-quality camera systems that integrate video, voice, data, and a web interface. By logging on to the same website, colleagues from several locations can participate in a videoconference. Once the meeting is under way, other “virtual in-person” tools are available, such as whiteboards, electronic walls, and interactive software.

Several large companies, like IBM, consider videoconferencing a vital tool in the virtual world. And, throughout the interviews conducted to research this book, most virtual managers expressed a positive view of videoconferencing capability and interest in using it more often to build human interactions, particularly in light of smaller travel budgets. By and large, the managers agreed that videoconferences afford their teams these benefits: a closer connection than conference calls, the ability to conduct unstructured conversations, and an economical way to simulate live conversation.

Future communication mediums are moving toward creating a workplace that, in spirit and feel, is as close as possible to live, inperson meetings. Here are some tips for getting the most out of your videoconference:

1. Test the working conditions of your equipment. Do it before any important conference.

2. Make sure you are in a quiet location. You want to minimize or eliminate disturbances. Don’t shuffle papers, scrape your chair, tap your pencil, hum, or do other distracting, noisy activities.

3. Have a set of simple guidelines in place for all videoconferences. For better or worse, team members can’t hide on camera. Since you don’t want anything to interfere with the purpose of the meeting itself, good manners and appropriate behavior are important. Keep your guidelines simple. They should be easy to follow and easy to remember. For example, look at the camera, don’t fidget, speak into the microphone clearly and slowly, and pause frequently.

4. Remind participants of these guidelines early in the session. The facilitator or moderator should advise participants of the basic rules of the videoconference before general interaction begins. This includes both general etiquette and any specific rules the moderator deems necessary.

5. Begin on time, stick to the agenda, and end on time, thereby allowing participants to keep other commitments. If you gain a reputation for running meetings efficiently, then fewer participants will be no-shows or drop out of the meeting prematurely. It is helpful for the conference’s host to arrive a few minutes early to greet each participant. That way you can head off any premature discussions participants may engage in before everyone is in place.

6. Have all participants say hello and introduce themselves. After all expected participants are in view, the moderator should introduce each person and briefly state the person’s responsibilities on the call. This is especially true if there are guests or newcomers on the call. Even though you may never meet in person, it’s a good relationship builder and gets the shyest of people to at least say their name.

Web Conferences. Today, web conferences are commonplace because of the ease of the technology. Attendees join a web conference by clicking on a link (invitation) in an e-mail or web page, or by downloading an application on their computers that gives them access to additional tools (e.g., whiteboard, chat, polling, and breakout rooms). These features allow you to get a pulse on who is contributing what.

What techniques can you use in a web conference to ensure that all attendees are engaged? From facilitating these types of conferences I have learned that the basis of a successful meeting is to set the expectation up front that all attendees are expected to participate. By signing on as separate users, everyone can engage in the features offered by web conferences.

If there are newcomers to your web conference, spend an extra minute helping these attendees feel comfortable. If the web conference is a large one, set up a brief preconference walk-through. You will find that those who take you up on this offer will appreciate this extra attention, and you will be rewarded with a fully present attendee.

During the meeting use all the tools at your disposal, and make sure that everyone knows how to use them. Brainstorming can occur using chat. Paired chat is another option, where team members are paired up in a short brainstorming assignment. Polls provide an easy electronic record of key discussions, and during a debrief, the top answers to your polls or surveys can become your action plan.

Guidelines for Maximizing Participation in a Video or Web Conference

![]() Ask all participants for agenda items and distribute the agenda before the meeting.

Ask all participants for agenda items and distribute the agenda before the meeting.

![]() Make sure all technical tools are set up before the meeting.

Make sure all technical tools are set up before the meeting.

![]() When the conference begins, identify yourself (as host or facilitator) and briefly mention the names of everyone who is present and introduce anyone who is new. Make sure to clearly note when anyone enters or departs from the conference session.

When the conference begins, identify yourself (as host or facilitator) and briefly mention the names of everyone who is present and introduce anyone who is new. Make sure to clearly note when anyone enters or departs from the conference session.

![]() Pause at regular intervals; ask for others’ views and/or questions.

Pause at regular intervals; ask for others’ views and/or questions.

![]() Refrain from behavior that could alienate participants, such as long monologues or extended conversations with people sitting next to you.

Refrain from behavior that could alienate participants, such as long monologues or extended conversations with people sitting next to you.

![]() Look into the camera when speaking, not at people sitting in the same room.

Look into the camera when speaking, not at people sitting in the same room.

![]() Be aware of lag time, and don’t jump to new points, which may confuse listeners.

Be aware of lag time, and don’t jump to new points, which may confuse listeners.

![]() Make sure that main points are summarized and action items are clearly stated and then distributed to each participant.

Make sure that main points are summarized and action items are clearly stated and then distributed to each participant.

Relationships

Relationships are the third type of Context Communication. They are the glue that holds team members together. To overcome the difficulties of working across physical distances, relationships need to be constructed using tools (e.g., telephone and/or computers) that were not designed to build relationships.

After the initial Team Setup phase, you still need to develop team relationships, as members continue to learn about their teammates’ personalities, work styles, moods, friendships, and career goals. Without the opportunity to lunch with colleagues, it’s up to you, as team leader, to build relationships by creating the missing social elements in different ways. Relationships create the social communication context from which you can infer information about your teammates.

How do virtual managers foster critical relationships? The overwhelming message sent by people who walk in your shoes is to find a way to build the relationship with your team. From a leader perspective, be accessible, reach out, and connect with your virtual team:

“You have to build relationships with people you don’t see, and you need them more than they need you. No one will do it for you. So force yourself to call everyone on your team; maintain relationships, because if you are out of sight you are out of mind for a lot of people. It’s not comfortable. But I make sure I do it.”

—MANAGER, CONSUMER ELECTRONICS COMPANY

“I make sure that I am 100 percent accessible and I help my employees along because in virtual teams, people tend to hide behind computers, and you are not going to establish relationships via e-mail. So I reach out to them and bring them along. I learn from them and incorporate their ideas. My biggest value-add is being 100 percent accessible.”

—GLOBAL MOBILITY MANAGER, CREDIT CARD COMPANY

Recall Maria’s situation, as set out earlier in this chapter. In scenario A, you worked in the same office as Maria and observed her personality, work ethic, moods, and personal commitments. In scenario B, you had to infer cues about virtual Maria. Let’s say virtual Maria wants to establish better connection with her teammates and develop better work relationships. She must overcome the three relationship context challenges: (1) isolation, (2) personality, and (3) history.

Relationships Challenge 1: Isolation

“I’m on my own island. I’m by myself,” a virtual leader at an information solutions company told me. Let’s call him the Islander. He said, “I need to figure things out by myself.” The Islander was unaware of what teammates were doing and felt like he worked in a vacuum. “I’m on conference calls,” he said, “and I don’t know what anyone looks like or who they are. I met my first manager, but not my second or third manager. The most information I can get about teammates is their online profile or résumé, but it doesn’t even have a picture. It doesn’t tell me very much about who they are.”

He goes on to describe his communication challenges: “It’s easy to be in your own world since you don’t have quick sidebar conversations as you would in the office. All communication is behind e-mails, and I have no idea how things work. E-mails can be misread, and it’s hard to know if something cool is happening in the company because there is no visibility.”

When asked about relationships with his immediate team, he describes his interactions as follows: “If you are not there, people don’t know you. In an office people can see you and know what you’re doing. There’s something about going into someone’s office and talking about what’s going on—have a conversation, agree and shake hands. I miss that. When you are out there alone, people have no clue what’s going on and they can forget you.”

The Islander’s situation summarizes two main problems regarding the isolation that can occur in virtual teams: the need for managers to build working relationships with their team, and the need to engage team members with each other when a sense of team is lacking.

Most of the time, isolation is associated with feeling disconnected from teammates because of the lack of personal interaction or social connection after work hours. Many people hope to attend an occasional in-person meeting, budgets permitting; they believe that interacting face-to-face every few months helps build relationships. Despite the cost factor, many people point out that face time is critical.

If face time is eliminated, or drastically reduced, what can you do to bring together your Islanders and assemble your castaways? How can you facilitate the human connection in this virtual world? What tools are at your disposal to pull your team together and build relationships so that people feel connected?

Your greatest contribution as a virtual leader is to find that connection with people and keep it alive, because the human factor is still the most powerful element in our virtual world. Shortly, we will explore ways to do that.

Relationships Challenge 2: Personality

“I wish that when I started, somebody did an overview with me of the personalities involved, because it takes so long to know the people. If you want this person to do something, you have to do X. For another person, you need a totally different approach. So-and-so only wants a one-sentence summary to approve budgets. Personality differences take a long time to learn because there’s so much disparity in how people like to do things. Everybody has their own preference. I have to figure out what’s going to work with each person.”

—MANAGER, INTERNATIONAL NONPROFIT ORGANIZATION

Let’s return to Maria, that hardworking consultant. She’s a diligent, responsible project manager whom you have counted on in the past. Knowing her personality, work patterns, and preferences helps you determine the best approach in terms of how (communication medium) and when (time of day) it is best to reach her. You do not have to waste time wondering where Maria is, if and when she will contact you, since you know she checks e-mails during the evening. If your request isn’t clear, Maria will call to discuss her questions. There would be no need to plan a backup scenario.

Now, let’s return to your virtual world. Although it is important to be sensitive to others’ styles in all work situations, for virtual teams it often means the difference between a frustrating and a rewarding relationship. How can you learn about your teammates’ work style, preferences, and personality when you don’t have opportunities to observe them in person? Let’s say you work with Walter, who has communicated several times that he prefers all the information up front, even if the e-mail is long. When you inadvertently omitted some details about your request he was clearly annoyed, although he did not call you for clarification (Walter claims to be allergic to the phone!). If you work on projects for Maria and him, how can you adapt to their different behavioral cues? Besides handling the Team Setup phase well, what can you do? As the manager, an important part of your role is to create social knowledge so that team members learn each other’s preferences.

Relationships Challenge 3: History

Virtual teams regularly share data files, information, and updates, but do they share history? With team members often joining and departing midway through projects, history becomes difficult to capture. It is hard enough to learn the team’s lingo, norms, and communication styles. Now there are past experiences to be aware of and remember. Think about a good childhood friend of yours, someone you grew up with, or with whom you shared something meaningful. A bond was formed, and when your friend calls, you often smile to yourself. No question you would go the extra distance for this person if asked. That type of connection doesn’t exist with virtual teammates. Nevertheless, creating shared experiences can open communication lines to increase understanding. Your shared history will motivate your colleagues to help you and to let them know that you can be counted on as well.

As a manager, one of your jobs is to create the conditions for contact to deepen into history—and that requires regular contact between people so they can make and grow work-related connections. The secret sauce to overcoming isolation in the virtual world is to create what I call a virtual watercooler.

Find Your Rhythm

All teams, virtual or not, fall into routines. These routines can lead to a comfortable operating rhythm, which forms the pulse of a high-functioning unit. You can help develop this rhythm by pushing for regular communications. Think of yourself as a concert conductor who leads the orchestra, making sure that the music flows at just the right tempo or rhythm. That means helping those who feel isolated find the connection, working to build their social knowledge, and creating the conditions for isolated events to become shared history.

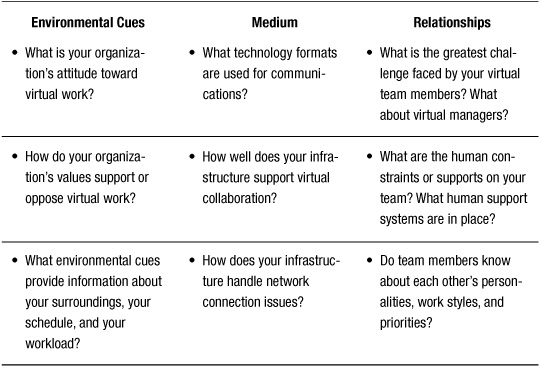

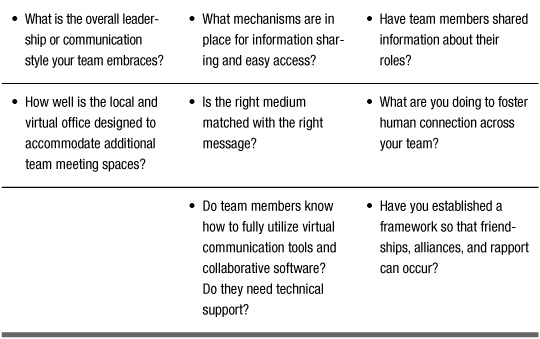

The Link Between Context Communication and Accountability

Good communication unites your team. And creating the context for shared understanding is one of your key tasks. Complete the Virtual Roadmap exercise at the end of this chapter, which is written as a series of questions, to once again reflect on the multiple layers of Context Communication. Think about your own team as you consider the questions in the Virtual Roadmap and use them to frame appropriate communication mechanisms to enhance your virtual context.

A virtual team is like any community in that its culture is a product of common norms and ongoing interactions that lead to shared experiences. Team members may not verbalize it, but they look to you to provide opportunities that make this happen. When context is communicated well, it builds accountability and trust, without which teams fail to achieve superior performance. As you will see in the next chapter, trust is based on experience, reputation, and reliability.

YOUR VIRTUAL ROADMAP TO CONTEXT COMMUNICATION