Chapter 5. Design Defense

“If you can’t explain it to a six-year-old, you don’t understand it yourself.”

—Albert Einstein

The Design Defense is 75 minutes long and provides an opportunity to present and defend your submitted design to a panel of architects.

You must adhere to several procedures during the defense.

• Prepare a presentation for the panel that outlines key aspects of your design.

• When arriving at the session, personal items such as laptops, cell phones, and other items will be stored in a secured location.

• Bring a USB key or other media containing your presentation. Presentations are limited to Microsoft PowerPoint or SlideRocket format. Do not bring additional items or props for the defense.

Bringing printed copies of the design into the room is not permitted. Include design references as part of the presentation slide deck. Note that panelists, observers, and the moderator cannot accept gifts or promises of alcohol from the candidate. You wouldn’t bribe your test proctor, would you?

When the presentation is loaded and ready, the moderator reads several prepared remarks covering the guidelines of the defense. After the moderator activates the VCDX timer, the floor is yours. Do not be overwhelmed by the situation. Do not over think it. Be well organized and focus intently.

The time requirements are adhered to using a web-based timer. Figure 5.1 shows an example of this timer.

Figure 5.1. The rather expensive VCDX timer

Design Overview Presentation

The defense phase begins with a short presentation covering the submitted design. This presentation leads to several lines of questioning from the panelists. Your goal is to demonstrate your skills by answering the panelist questions about your design. The moderator will remind you how much time is remaining at specific intervals. Feel comfortable moving back and forth between different parts of your presentation to answer panelist questions.

The following is an example outline for the presentation.

• Introduction, with contextual information about the project (such as business drivers and challenges)

• Key design decisions for each blueprint area

• Additional information showing alternate design options

• Reference diagrams to support answers to panelist inquiries

No restriction covers the minimum or maximum number of slides to include. The only constraint is that you should be able to complete your presentation in 15 minutes if you are uninterrupted. Typically, panelists jump in during the presentation to inquire about specific decisions, this is to understand your approach and potential clarify misunderstandings within the design. Keep your answers succinct, to maximize the amount of time.

No specific right or wrong way exists for creating a presentation. Create a structure that is comfortable for you.

Presentation guidelines:

1. Cover key requirements and design decisions.

2. Include any relevant artifacts so that you can refer back to them.

3. Minimize chart junk or flashy transitions. Content is king.

4. Do not include superfluous information. Talking about your entire CV and qualifications just eats up valuable time.

5. This is not a license to cram the entire design document into slide format. The presentation serves as a reference and a starting point for questioning.

Example Presentation Slides

Your slides should reflect key aspects of the project, including these:

• Key requirements, constraints, assumptions, and risks

• Topology of the infrastructure

• Logical components (storage, networking, clusters, and workloads)

• Major obstacles, problems, and risks and resolutions

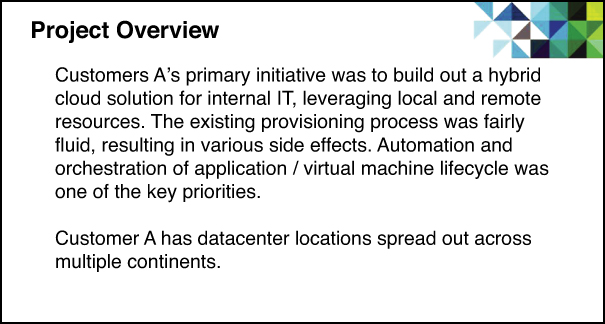

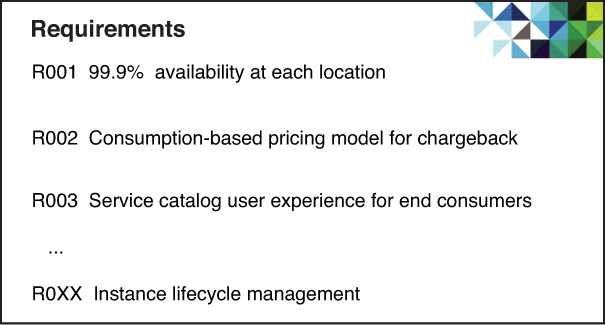

Figures 5.2 through 5.5 provide examples of a design overview presentation.

Figure 5.2. Project overview slide example.

Figure 5.3. Project requirements slide example.

Figure 5.4. Constraints slide example.

Figure 5.5. Project risks slide example.

Reference Material

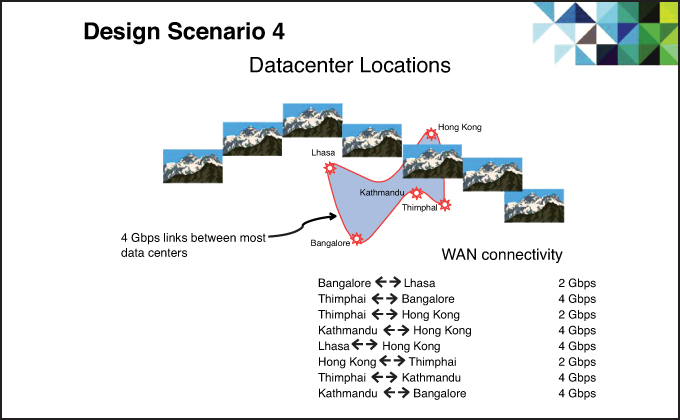

Include reference slides at the end of the presentation that depict topology, connectivity, hardware components, software components, and other artifacts that will assist in responding to questions. This allows you to refer to a diagram instead of needing to whiteboard it, as demonstrated in Figure 5.6.

Figure 5.6. Reference material slide example.

Know Your Design

Be intimately familiar with all aspects of your design. A fully prepared candidate can whiteboard an entire design, if called upon. Of course, we do not expect or want candidates to do this during the defense due to time constraints.

If the design was coauthored with others, you are still responsible for understanding all aspects of the design and supporting documentation.

Understand both sides to every design consideration. Being able to address conflicts or issues is a core trait of an architect. What issues were present, and how were they addressed? What was your recommendation to the customer? How would you address or mitigate these issues today?

Referring to “best practices” alone is not sufficient. Understanding the logic behind the best practice is what counts. Best practices are specific to certain customers and use cases.

Designs often include fictional components to map more closely to the VCDX blueprint. In this case, be sure to align the fictional components with the overall requirements of the project. Seek feedback from your peers to ensure that they understand the decision points, justification, impact, and associated risk.

Entirely fictitious designs run the risk of resulting in heavily over engineered designs due to the amount of freedom available. The most over engineered design is neither exciting nor interesting, and discerning skill is difficult. To avoid this trap, leverage your peers to keep the design grounded. Requirements and constraints help shape and focus problems, providing clear challenges that lead to innovative and creative solutions.

Defense Strategy

Your goal in the defense is to showcase your skills as an architect in each domain area. Every candidate has an individual style, developed over years of experience. Having a good design on paper is not enough. Being able to explain and rationalize the design decisions made is critical. Think of it as a final presentation of design to a customer. If you lack this experience, tailored practice and high-quality feedback can make a dramatic difference.

If certain sections are not covered in the defense, it is difficult for the panelist to make an assessment. Answer the panel in a manner that demonstrates understanding and conviction of your design choices. Attempt to be as clear as possible, to help the panel separate the signal from the noise.

Listen to the panel. When they ask you to explain how you came to the design, do that—don’t just explain the facts.—Yvo Wiskere, VCDX-025

When defending the design, do not rely on “just because” or “because it’s a best practice.” Be prepared to explain why you used a best practice. You must be able to respond interactively and expand on how it relates to your design. The panelists are not attempting to induce the maximum amount of stress, but they do have to validate your understanding. Arguments are judged on how well thought-out the position is, the supporting reasoning and evidence, and how consistently the topic is argued.

Be able to articulate every aspect of your design. This is the most common piece of advice past defendants have provided. If you are not familiar with any particular component, put in the work to strengthen that weakness and build up the knowledge to rationalize all key design decision.

Ask yourself, “Why did I make this decision?” to all your design considerations. If you cannot answer why you made it, it means you do not know your design. —Chris Colotti, VCDX-037

Successful candidates have shown several common traits. First, they put in the effort to think through the questions that a panel was likely to pose and how to respond. Second, they studied the rubric to identify deficient areas and spent time strengthening those areas. Third, they practiced placing themselves in a defense-type situation that prepared them for the actual experience. Seek out opportunities to conduct design-type workshops to condition your mind for the actual experience.

Practice Leads to Success

Recruit peers to review your design and application package. If you are lucky enough to find more than one person to assist, it is good to get perspective from individuals with different backgrounds and specialties. Accurate feedback is the single most powerful way to prepare yourself, improve your skills, and increase your chances of succeeding. Try to take any suggestion positively.

The biggest draw for the VCDX boot camps is the opportunity to participate in a defense simulation. This is a great chance to get feedback from actual VCDX panelists. The group environment is also useful for fostering discussion and ideas, especially when peers are throwing rocks at your design. Engage in deep conversations with your peers on design considerations. If you encounter a problem, force yourself to come up with a suitable explanation. You do not learn from experience itself; you learn from reflecting on experience.

Plan to do a dry run several months before the defense date. This gives you time to make adjustments and improvements to your design and to redo the practice defense. As with most academic pursuits, gaining deep understanding often requires time. Candidates are often too close to the design and are not mindful of other perspectives. Do not rush the process—this could negatively impact your confidence at the actual defense attempt.

Preparation Checklists

The following checklists provide practical reminders of important steps in the process.

Checklist: Preparation for the Defense

• Review all aspects of your design.

• Get peer review and/or feedback (mock defense, VCDX boot camp).

• Recognize your weaknesses, and strengthen them.

• Rest before the session.

• Arrive around 10 to 20 minutes early.

• If you experience anxiety, use relaxation techniques (such as deep breathing).

Checklist: Defense Overview Presentation

• Cover the project and important points such as requirements, constraints, assumptions, and design considerations. Include key decision points and components representing the areas identified in the blueprint:

[•] Requirements

[•] Constraints

[•] Assumptions

[•] Risks

[•] Availability

[•] Manageability

[•] Performance

[•] Recoverability

[•] Security

[•] Conceptual model

[•] Logical design

• Create a reference section that includes material to support your defense. This can include diagrams, tables, and other material that you plan to refer to during the defense.

• Rehearse your presentation, preferably in front of peers.

• Do not include extraneous information.

Checklist: Design Defense

• Preparation

[•] Know all areas of your design.

[•] Anticipate questions from the panelists.

[•] Identify design strengths.

[•] Identify design weaknesses.

• Execution

[•] Answer questions with concise responses.

[•] Refer to your presentation supporting materials section (diagrams and tables).

[•] Allow panelists to complete their questions before you respond.

[•] If you do not understand a question, ask for clarification.

[•] Remember that you can increase or decrease your score based on your interactions with the panelists and your responses to questions.

[•] Remain professional throughout (the panel is your customer).

Review

The first phase of the VCDX defense begins with the presentation and defense of the submitted panel. During 75 minutes, panelists ask questions to discern whether you can demonstrate expert-level architecture design skills. The goal is not to make your life miserable. The goal is to validate architects who can proliferate expert-level design technique worldwide.

Candidate success relies on the following factors:

1. Consulting experience

2. Technical experience

3. Performance the day of the test

All this is attainable by anyone with the proper experience, motivation, and preparation. Conducting mock defenses and peer review is the best approach to take. The point of going through the motions of a mock defense is to make the situation feel more natural. Ensure that your peers include individuals who can challenge you and throw curveballs at your design. Leverage the provided checklists to improve your level of preparedness.

Know your design. You might have seen this stated earlier in this chapter. Many candidates fail because they simply did not consider all the options and decisions that went into their design. In most cases, this is due to a lack of preparation time. That is not to say that merely memorizing and understanding your design is sufficient enough to pass—you must be able to think on your feet, synthesize problems quickly, and embody other qualities of an architect. However, not knowing your design is such a common theme among those who fail that we must point it out.

Remember that you should always be demonstrating your knowledge and understanding. Every question you answer is a chance to show what you know and understand. But keep your answers relevant and concise. Answer briefly enough that you get through everything, but do not answer so briefly that the panelists cannot gauge understanding. If the full answer escapes you, demonstrate what you know and how you can think about the question.