Trends in Fixed Income: Investing in Bonds*

Tom Lydon

*Chip Norton, who contributed substantially to this, is the managing director of Fixed Income Strategies at the Naples, Florida–based Wasmer, Schroeder & Company. Chip has specialized in the fixed income markets for more than 25 years and is author of Investing for Income (1999, McGraw Hill).

It can be easy to forget about bonds, especially during the good times in the market. Often, this is a segment of the market that investors might tend to dismiss as something for “conservative” investors who are nearing retirement. But recently, the bond market has been getting far more attention as allocations shift from equities and from alternative investments. Indeed, from a risk/return basis, many parts of the bond market look very appealing compared to almost any asset class.

Whether that’s true or not, bonds do have one thing in common with the rest of the market: They have their own trends. Bonds also range on a scale from “very safe” to “very aggressive” (and risky). Risk in bonds comes in a few different flavors, including traditional return volatility as measured by standard deviation. However, bonds also have interest rate risk, which is their sensitivity to changing rates. Longer maturity bonds will be more sensitive to interest rate changes while short-term funds will have less sensitivity. Knowing this, an investor can determine the risk parameters they might want to accept in a fund and position it appropriately in an asset allocation.

The different types of bonds, from safest to most risky, are as follows:

• U.S. Treasury bonds—These bonds are considered among the safest because the government of any stable country rarely defaults on its debt. In exchange for safety, yields (the interest or dividends received) are generally low. The yields on Treasury bonds hit 50-year lows in 2008 as investors sought safety from the markets. In fact, at one point, yields went negative—meaning people were paying the government to hold their money.

• Municipal bonds—These bonds are issued by states and localities. Although they’re not as safe as Treasuries, they do offer a measure of safety. It’s unusual for cities and states to go bankrupt because they can usually raise revenue through taxes—but bankruptcies do happen. A bonus of these bonds is that they’re free from federal taxes.

• Corporate bonds—These bonds reside on the higher end of the risk spectrum, because corporations can—and do—default on their debt. Because of their higher risk, they come with high yields.

• Junk bonds—These bonds, sometimes known as high-yield, are the riskiest of all, rated below investment grade at the time of purchase. These types of bonds are also frequently known as high-yield debt. Of course, because of their extreme risk, they tend to pay the most handsome yields.

• Foreign bonds—You don’t have to limit yourself to the United States when it comes to bonds. Foreign governments, municipalities, and corporations also issue debt, denominated in their own currencies. There are different levels of risk in these bonds, just as there are in the U.S. bond market. The principal risk with these is currency risk, which is the potential for loss because of exchange rate fluctuations.

Factors to Consider

Bonds are tricky instruments, subject to a number of factors. There are several points investors should understand:

• As bonds increase in price, their yield tends to go down. In periods of high demand (such as market turmoil, when investors are seeking safety), the price of a Treasury bond tends to rise while the yields fall (see Figure 1). Prices of corporate bonds in down markets, however, tend to fall while yields increase—after all, would you be so keen to invest in a corporation’s bonds in a recessionary climate?

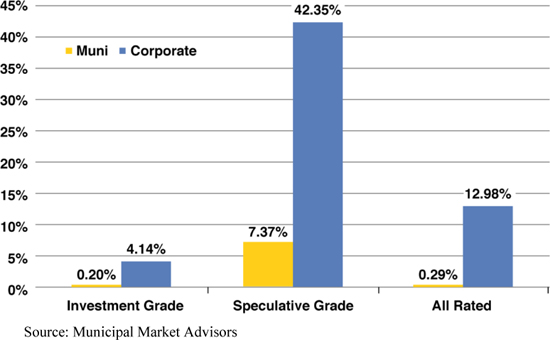

• Credit quality is one of the main criteria when it comes to judging the investment quality of a bond. The rating clues investors in to a bond’s “credit worthiness” or default risk. The rating is a grade given by a private, independent ratings service (such as Standard & Poor’s or Moody’s), which indicates their credit quality. These ratings are given to illustrate the bond issuer’s strength or, in other words, their ability to pay a bond’s principal plus interest in a timely manner. Credit quality does change over time and often deteriorates during recessionary periods. Indeed, prior to the market crash in 2007 and 2008, the default rates on high bonds were as low as 1.5%. The expectation today is that default rates could exceed 15% on this type of bond. Conversely, municipal credit quality has been historically low and is expected to continue to show low defaults (see Figure 2).

Figure 1 10-year U.S. Treasury bond, 1970–2008

Figure 2 Municipal market versus corporate market default credit summary, 1986–2008

The ratings services use their own letter grades, but as an example, Standard & Poor’s uses the following scale:

• AAA and AA—High credit quality

• AA and BBB—Medium credit quality

• BB, B, CCC, CC, and C—Low credit quality (also known as junk bonds)

• D—Bonds in default

• Yield refers to the income return on an investment and is expressed annually as a percentage. Bonds have four yields:

• Coupon—The bond interest rate fixed at issuance.

• Current yield—The annual return earned on the price paid for a bond.

• Yield to maturity—The total return an investor receives by holding the bond to maturity. The yield reflects all the interest payments from the time of purchase to maturity, including interest on interest. It also includes any appreciation or depreciation in the bond’s price.

• Tax equivalent—Nontaxable municipal bonds will have a tax equivalent yield, which is determined by an investor’s tax bracket.

One of the biggest risks with bonds is interest rate risk. Interest rates and bonds share an inverse relationship: As interest rates fall, prices increase, and vice versa. Why does this happen? Typically, it’s because investors are trying to lock in the highest rates possible, for as long as possible. To do so, they’ll get existing bonds that pay a higher rate than the prevailing market rate. This leads to an increase in demand, which means the price increases and the interest rate falls. A good rule of thumb is that bonds with shorter maturities will suffer less from an increase in interest rates. But if you’re holding bonds in a period of low inflation and low yields (2008 is a perfect example), long-term bonds tend to deliver the biggest gains.