7

Wellbeing policy and measurement in the UK

We must measure what matters – the key elements of national well-being.

Jil Matheson, UK National Statistician (2010)

There are developments in wellbeing policy and measurement in many countries, with the close involvement of international organisations such as Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (the OECD) and the United Nations (see Appendix). We take the United Kingdom as a case study in this chapter, looking in particular at the Measuring National Well-being programme of the United Kingdom Office for National Statistics (ONS). This is because, from our close involvement with the programme, we think that there are a number of features that are worth highlighting and which should be applicable more widely.

The Measuring National Well-being programme (which we will call MNW) builds on 40 years of social reporting by the ONS, especially through an annual volume Social Trends, aiming to present a wider picture of life in the United Kingdom than that gleaned from looking only at economic statistics. In setting up MNW, the ONS was able to draw on trail-blazing work, including through building a close working relationship with the Centre for Wellbeing at the New Economics Foundation. The centre had been established some 10 years ahead of the ONS programme and had consistently sought to understand, measure and influence wellbeing, both directly and by alerting policy makers to the issue.

ONS became increasingly aware during the first decade of the new millennium of calls for measures of wellbeing and progress to go ‘beyond GDP’. It was also apparent that meeting that interest should be without any reduction in ONS's commitment to publishing full and timely national accounts and to continue to develop those accounts in line with international developments and evolving user requirements, for example, on the treatment of the output of public services. ONS staff examined the Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi recommendations and quickly realised that these recommendations provided a good framework for how to proceed. The recommendations struck many chords with existing (albeit incomplete) statistical outputs that contribute to a fuller picture of national wellbeing and progress. For example, work on human capital, social capital, natural capital, the measurement of household wealth and analyses of the distribution of income and wealth could be brought into, and taken forward under, the MNW programme.

The United Kingdom already had a well-developed and regularly published set of sustainable development indicators (SDIs). These were not at the time the responsibility of ONS, though ONS indicators were included. This did raise the issue of the fit between measures of national wellbeing and SDIs.

There were three innovative aspects to MNW. First, it kicked off with a period of considerable public engagement and debate around the question ‘what matters?’ The second major development was that, for the first time, ONS included subjective wellbeing measures in its regular household surveys. The questions resulted from an intensive period of investigation, made possible by building on long-established academic research and survey work on subjective wellbeing. The questions were not just for ONS surveys, but the intention was to include them in other government surveys, to create a widespread picture of wellbeing in different policy areas. This reflects the third eye-catching aspect of MNW, that of working closely with policy makers prompted by government wanting to give greater attention to wellbeing in policy.

We will return to the MNW programme shortly. First, here is a timeline to illustrate a number of events, developments and reports across the United Kingdom that, with hindsight, we can see as the evolution of measures of national wellbeing and progress. It is a far from complete history. We have selected developments that we see as illustrative of the breadth of interest and which appear to have acted as milestones and have taken forward debate on measuring progress and wellbeing. The timeline should also be seen against a backdrop of much work on wellbeing measurement in academic centres and by researchers in nongovernmental organisations, producing many academic papers relevant to wellbeing and progress and increasing media coverage.

- 1941: Analysis of the Sources of War Finance and Estimate of the National Income and Expenditure can be read as prototype set of official national accounts, and provides foundation for UK National Accounts published from late 1940s onwards by the Central Statistical Office;

- 1960s: Central Statistical Office starts publishing income distributions, including annual analysis of the effect of taxes and benefits on household income;

- 1970: Central Statistical Office launches Social Trends as annual collection of economic, social and environmental statistics describing life in Britain;

- 1991: Alternative Economic Indicators by Victor Anderson;

- 1996: Questions about life satisfaction added to the British Household Panel Survey;

- 2000: The New Economics Foundation establishes Centre for Wellbeing, working collaboratively and producing many reports (e.g. National Accounts of Wellbeing, January 2009);

- 2000: Local Government Act gives local authorities the power (but not a statutory duty) to promote social, economic and environmental wellbeing in their area;

- 2001: Welsh Assembly Government's first national economic strategy notes that ‘increasing GDP does not automatically lead to a better quality of life’;

- 2002: ONS publishes first partial set of UK Environmental Accounts and experimental Household Satellite Account;

- 2002: Prime Minister's Strategy Unit publishes Life Satisfaction: The State of Knowledge and Implications for Government;

- 2005: Happiness: Lessons from a New Science by Richard Layard published;

- 2005: UK Sustainable Development Strategy Securing the Future commitment to exploring policy implications of wellbeing research. Sustainable Development Indicators published;

- 2005: ONS article about the measurement of social capital in the United Kingdom published;

- 2005: Audit Commission publishes list of local quality-of-life indicators;

- 2005: Review of the Measurement of Government Output and Productivity in the National Accounts. The Atkinson Review argued for a principled approach to the task of measuring the value of public services. ONS sets up a UK Centre for the Measurement of Government Activity;

- 2006: The Economist's Christmas edition leads with ‘Happiness (and how to measure it)’;

- 2007: Institute for Economic Affairs research monograph argues that happiness research cannot be used to justify government intervention;

- 2007: ONS Economic & Labour Market Review article on Measuring Societal Wellbeing published;

- 2007: Scottish government includes quality of life in its principles and priorities;

- 2007: Conservative Party Quality of Life Policy Group includes recommendation ‘for the UK to agree on a more reliable indicator of progress than GDP, and to use it as the basis for policy-making’;

- 2008: Young Foundation publishes ‘Local wellbeing: can we measure it?’ as part of Local Wellbeing Project with number of partners;

- 2008: Climate Change Act sets target to reduce UK's greenhouse gas emissions by at least 80% (from 1990 baseline) by 2050;

- 2009: Report of the Commission on Measuring Economic Performance and Social Progress (led by Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi, with three UK members);

- 2009: Royal Statistical Society Statistics Users' Forum conference on measures of progress;

- 2010: David Cameron, then leader of opposition (Prime Minister from May 2010), sets out his views on the importance of general wellbeing, in TED talk on the next age of government;

- 2010: Marmot Review on reducing health inequalities in England includes key message that ‘economic growth is not the most important measure of our country's success’;

- 2010: UK government Budget Report includes commitment to developing broader indicators of wellbeing and sustainability;

- 2010: ONS Measuring National Wellbeing programme launched, along with conference on wellbeing policy;

- 2010: Economic and Social Research Council/National Institute of Ageing Workshop on the Role of Wellbeing Measures in Public Policy, Washington DC;

- 2010: Young Foundation report The State of Happiness: Can Public Policy Shape People's Wellbeing and Resilience?;

- 2010: The ESRC's first overview making the case for the social sciences is on wellbeing;

- 2011: UK participation in Eurostat Sponsorship Group and Task Forces on GDP and beyond;

- 2011: Liberal Democrats Policy Paper A New Purpose for Politics: Quality of Life;

- 2011: PWC and Demos report on economic wellbeing ‘Good growth’;

- 2011: House of Lords short debate on national wellbeing;

- 2012: Legislation enables public authorities to have regard to economic, social and environmental wellbeing in their procurements;

- 2012: UK participates in UN High Level meeting on wellbeing and happiness;

- 2012: Legatum Institute Commission on Wellbeing Policy launched, chaired by Lord Gus O'Donnell, former UK Cabinet Secretary;

- 2012: House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee reports on Sustainable Development Indicators;

- 2012: ONS publishes roadmap Accounting for the Value of Nature in the UK to incorporate natural capital into the UK Environmental Accounts, linked to Natural Environment White Paper commitment to developing natural capital resource accounting;

- 2013: Environmental Audit Committee launches enquiry on the ONS Measuring Wellbeing programme and how government policy is using wellbeing research and analysis;

- 2013: London School of Economics ‘Growth Commission’ aims to provide the authoritative contribution to the formulation and implementation of UK long-term growth strategy;

- 2013: UK National Statistician Jil Matheson, member of OECD High Level Expert Group, to continue work of Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi Commission;

- 2013: Prime Minister David Cameron co-chair of UN High Level Panel, reporting recommendations on eradicating poverty after the Millennium Development Goals expire in 2015.

On 25 October 2010, the British Prime Minister made a speech to the Confederation of British Industry, in which he set out a strategy for growth for the country and how ‘we can create a new economic dynamism in our country’ (Cameron, 2010b). Like many political leaders in the aftermath of the financial crisis and economic recession, David Cameron was concerned to answer the questions ‘where is the growth going to come from – where are the jobs going to come from?’ In a speech almost entirely devoted to growth, the Prime Minister also spoke about the wider role of government, touching on the issue of wellbeing that he had spoken several times about when he was the leader of the opposition, including the concept of general wellbeing (Cameron, 2010a). Mr Cameron said in his October 2010 speech, ‘In the weeks ahead, we will be setting out how we will bring a new emphasis on well-being in our national life, and how we will work with business to spread social and environmental responsibility across our society’.

Less than a month later, on 20 November 2010, the Prime Minister gave a speech on wellbeing during which he said, ‘today the government is asking the Office of National Statistics to devise a new way of measuring wellbeing in Britain. And so from April next year, we’ll start measuring our progress as a country, not just by how our economy is growing, but by how our lives are improving; not just by our standard of living, but by our quality of life' (Cameron, 2010c).

On that occasion, the Prime Minister was speaking at the launch of the UK Office for National Statistics (ONS) ‘Measuring National Well-being Programme’. ONS had established this (MNW) programme not only to meet the needs of government policy makers but generally to provide wider measures of the nation's progress beyond just focusing on Gross Domestic Product (GDP), to capture more fully economic performance, quality of life as well as environmental sustainability issues. The programme was greatly influenced by the report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress (the Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi report), published in 2009, which had concluded that ‘the time is ripe for our measurement system to shift emphasis from measuring economic production to measuring people's well-being’ (Stiglitz et al., 2010, p. 10).

The Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi report contained specific recommendations to national statistics offices. Other initiatives, such as the European Commission's GDP and Beyond project and the OECD's Global Project on Measuring the Progress of Societies, were adding to the impetus to look for new approaches to the measurement of quality of life (see Appendix for links). It is a fine point, but worth making, that the ONS programme was devised to respond to these international developments, reflecting interest in the United Kingdom in wider measures than GDP, as well as to the government's request. The ONS programme has been misreported in the media as being to produce Mr Cameron's Happiness Index, which is wrong on all three counts. It is not just for the Prime Minister and was not commissioned by him: ONS initiated the programme, including bidding for funding from the government's Spending Review in June 2010; it is not just about happiness, even broadly defined to sum up psychological wellbeing, but about national wellbeing more generally; and it is designed to produce a number of measures, not a single index.

It had been 40 years since the last time that a British Prime Minister had been involved in the launch of a statistical programme. That was a much lower-key event, when Edward Heath held a reception to mark the publication of Social Trends. However, the context was the same, because Social Trends was established in 1970 to provide an annual picture of social conditions and changes, to complement the more extensive and well-known economic statistics. This was part of an effort to develop social statistics, which ‘had long tended to drag behind economic statistics in priority and quality’ (Moser, 2000).

The approach with Social Trends was novel: it was to be ‘exciting, non-technical and accessible to the general public well beyond Westminster and Whitehall. It had to be authoritative with the statistical material beyond criticism. But above all it was to be written and produced by us statisticians without political interference. What we included in any issue was up to us to decide, even if the material touched sensitive political nerves, and even if our comments were not popular with our political masters’ (Moser, 2000), according to Claus Moser, who was the head of the UK Government Statistical Service at the time.

The first edition of Social Trends recognized ‘economic progress must be measured, in part at least, in terms of social benefits’ and the fact that ‘it is just as important to have good statistics on various aspects of social policy’ (CSO, 1970) than it is to have good economic statistics. This was in part a response by the UK National Statistical Office to the social indicators movement, which was stressing the need for a wider set of ‘objective’ measures to allow a better assessment of the quality of life of people in the nation. It illustrated the dissatisfaction with the idea that the quality of life and progress could be measured using economic data alone, as Robert Kennedy had so eloquently expressed a few years previously (see Chapter 2).

Annual Social Trends reports were published for 40 years (and a quarterly publication trialled in 1998 but not continued), moving latterly to Web-based publication and rolling update of dozen or so chapters covering different aspects of life. Since 2011, ONS has evolved this publication into online outputs of the MNW programme, including an annual report on life in the United Kingdom.

The aim of the MNW programme is ‘to produce accepted and trusted measures of the wellbeing of the nation’ (taken from website, see Appendix). This does not in itself define the wellbeing of the nation. The programme is designed to help answer the question, ‘how is the UK as a whole doing?’ The concept of national wellbeing is meant to embrace everything needed to be able to answer the question in a meaningful, accepted and trusted manner, so that action and decisions at all level, from the individual to the government, can be taken. In these terms, national wellbeing, or how the nation is doing, should then address the present state of the nation, whether progress is being made and if current progress is sustainable in the longer term: all of these dimensions (and more) are wrapped up in the idea of national wellbeing.

Given the timing of the MNW programme, and its acknowledgement of the influence of the Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi report, it will be no surprise that MNW is also about looking at ‘GDP and beyond’. It is a statistical development programme that draws on a wide spectrum of statistical sources, so an early decision in the programme was that it should include headline indicators. The indicators are being formulated in the programme and are driven by covering the areas that matter to people. We will see that they relate to areas such as health, relationships, job satisfaction, economic security, education, environmental conditions and measures of personal wellbeing (individuals' assessment of their own wellbeing, or subjective wellbeing as we called it in earlier chapters). How these indicators were to be presented, the measurement framework, was still to be decided but it does look as if taking this approach to national wellbeing meant that the United Kingdom and the OECD would embark on somewhat different approaches, given that the OECD's How's Life? reports reflect a conceptual framework that distinguishes between current and future individual wellbeing. Drawing on the capabilities approach, the OECD measures current wellbeing ‘in terms of outcomes achieved in the two broad domains’ of material living conditions and quality of life. The OECD assesses future wellbeing by looking at the state of ‘some of the key resources that drive well-being over time and that are persistently affected by today's actions’ (OECD, 2013a, p. 21).

The intention of the MNW programme is to provide a framework for evaluating progress overall or identifying priorities. But it is not just aimed at policy makers, politicians and governments. The public, the media, nongovernmental organisations in civil society and businesses are all part of the intended audience for this and for all of the output of the ONS. Moreover, the MNW programme includes giving this wider public a voice. In doing so, the programme recognises that a national debate and ongoing consultations might help people in thinking about their own lives and choices. This is as well as more broadly seeking to raise awareness and influence ideas and debate about economic performance, social progress, the state of the environment and how all these interact.

One of the first phases of the MNW programme was, therefore, for ONS to host a wide-ranging national debate on measuring national wellbeing, with the strap line ‘What matters to you?’ The Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi Commission had encouraged – though this was not a formal recommendation – that roundtables be held in each country. Between November 2010 and April 2011, ONS's interpretation of a roundtable was to hold 175 events, attended by over 7000 people, around the United Kingdom, and to surround these events with extensive online activity. The debate generated more than 34 000 responses in total, mostly through online media including social media as well as website questionnaires.

In launching the programme with the Prime Minister, the UK National Statistician Jil Matheson spoke of statistics as the bedrock of democracy, in a country where we care about what is happening: ‘We must measure what matters – the key elements of national well-being. We want to develop measures based on what people tell us matters most’ (this quote is on the MNW programme website; see link in Appendix). The National Statistician published her reflections on the national debate, in July 2011 (these and supporting papers are published on the MNW website; see Appendix), including concluding that individual wellbeing is central to understanding national wellbeing, but not sufficient. There is a need for objective measures about the things that matter to people, such as health, education and access to public services, as well as subjective measures of personal wellbeing. National wellbeing must also take into account equity, sustainability and locality.

Working through the responses to the national debate enabled ONS to identify the key areas that matter most to people (ONS, 2011a) and to make initial proposals of domains and headline measures of national wellbeing. The initial proposals were then subject to further, but more targeted, public consultation, from October 2011 to January 2012. The aim of that consultation was to gather feedback on whether the domains and measures proposed reflected the broad scope of wellbeing, were easy to understand and whether users felt there should be any additions or changes. The ONS published a report summarising the 1800 responses, which showed that there was broad support for the proposed domains and measures (ONS 2012a).

To develop a framework for measuring national wellbeing, the ONS drew on an OECD working paper (Hall et al., 2010), as well as on other frameworks that had emerged in UK work and in the wellbeing literature. Note that the OECD now uses, in How's Life? (e.g. OECD, 2013a, p. 21), a different framework from that suggested by Hall et al. It is not that the United Kingdom has struck out in a different direction, but simply that there was need for a framework at that point in the UK programme. The challenge was to start structuring the measurement of national wellbeing with an eye to international developments while providing some common ground on which to engage nationally, including with ‘academics across the social sciences, life sciences and humanities’ (Spence et al., 2011, p. 2).

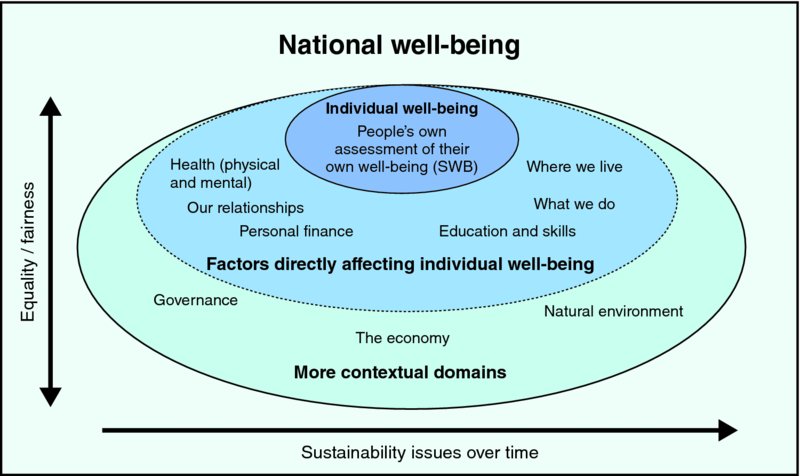

The framework for measuring national wellbeing published by the MNW programme in October 2011 is shown in Figure 7.1. It placed individual wellbeing at the heart of national wellbeing, identified six broad factors (such as health) directly affecting individual wellbeing and identified three more contextual domains (governance, the economy and the natural environment). Crucial in forming a full picture of national wellbeing are the distributions of each of the domains (suggested in the diagram by a ‘dimension’ of equity/fairness) and the sustainability over time of each domain (the bottom axis in the picture).

Figure 7.1 The Framework for Measuring National Well-being in the United Kingdom.

© Crown copyright 2011 – used under the terms of the Open Government Licence, http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/2/

Although the assessment of individual wellbeing through the measurement of subjective wellbeing sits at the core of the ONS framework, subjective wellbeing is only one component in the approach to measuring quality of life proposed by the Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi Commission (as we discussed in Chapter 4). However, ONS had not previously undertaken regular or extensive subjective wellbeing surveys and there was clearly an appetite for new measures of personal wellbeing, which is why this element of the MNW programme gained so much attention. (John Hall recalls that ONS published subjective wellbeing research and results from other sources in Social Trends in the 1970s, see his website listed in the Appendix.)

In April 2011 – the date referred to by the Prime Minister for the start of a new way of measuring progress – four experimental subjective wellbeing questions were introduced in ONS's Annual Population Survey (APS) of UK households. This allowed the subjective wellbeing questions to be analysed using at least some of the key determinants of wellbeing, as well as by demographic and geographic attributes. ONS took the decision to use only a few questions within a large sample (165 000 adults are questioned over the course of a year in the APS). This is in contrast to many in-depth studies of subjective wellbeing, which tend to have many questions exploring wellbeing conducted with a relatively small sample: two different approaches to using a fixed amount of funding. Using only a short set of questions makes it easier for the managers of other government social surveys to include them, to build a richer data set and to extend subjective wellbeing measurement into specific areas of government. These subjective wellbeing data are not just meant for analysing personal wellbeing, they contribute to the fuller picture of national wellbeing and progress in the United Kingdom.

The four questions asked by ONS in the APS are as follows:

- ‘Overall, how satisfied are you with your life nowadays?’ (This comes from the evaluative approach to measuring subjective wellbeing.)

- ‘Overall, to what extent do you feel the things you do in your life are worthwhile?’ (This is from the eudemonic approach.)

- ‘Overall, how happy did you feel yesterday?’ (This is about experience, specifically positive affect.)

-

‘Overall, how anxious did you feel yesterday?’ (This is about experience, negative affect.)

(All asked using a 0 to 10 scale where 0 is ‘not at all’ and 10 is ‘completely’)

Source: Hicks (2011).

These are very similar to the core measures described in the OECD's Guidelines on Measuring Subjective Well-Being (OECD, 2013b).

Although there are only four subjective wellbeing questions in the APS, ONS decided to use them as a way of capturing different aspects of subjective wellbeing identified in the literature (Tinkler and Hicks, 2011), accepting the recommendations of Dolan et al. (2011) to do this as the best way of providing a broad overview of subjective wellbeing. As noted in parentheses against the first question above, one approach is about life evaluation or a cognitive assessment of how life is going. Positive affect is about the experience of positive emotions and negative affect about the experience of negative emotions. These three aspects of subjective wellbeing are also discussed and endorsed in the Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi report. The fourth approach included by ONS is taken from the eudemonic perspective, concerned with positive functioning, flourishing and having a sense of meaning and purpose in life (e.g. NEF, 2011, and Huppert and So, 2013).

Alongside the APS data collection, the ONS has continued to use its monthly Opinions Survey (OPN) to carry out testing and development of subjective wellbeing questions, and to cover aspects of subjective wellbeing in more detail. OPN collects data from 1000 respondents in each monthly sample, so it is markedly smaller than the APS. Initial estimates from several months of the OPN and the APS were published in December 2011 (ONS, 2011b) and in February 2012 (ONS, 2012b). They show that the two surveys generate broadly similar results of overall subjective wellbeing of adults in the United Kingdom.

Hicks et al. (2013, p. 79) summarise the testing and development of the ONS subjective wellbeing questions. The testing of the questions, and how to ask them, included through split trials on question order, question wording (see Chapter 4), the use of show-cards, preambles for the ‘yesterday’ questions and response variation over days of the week. Data from the APS survey were used to demonstrate how responses varied month by month when the same subjective wellbeing questions were asked throughout the year. ONS has also looked at how face-to-face interviews compare with self-completion interviews. Dolan and Kavetsos (2012) found that respondents interviewed by telephone in the APS gave consistently higher scores for their subjective wellbeing than those meeting face-to-face with an interviewer.

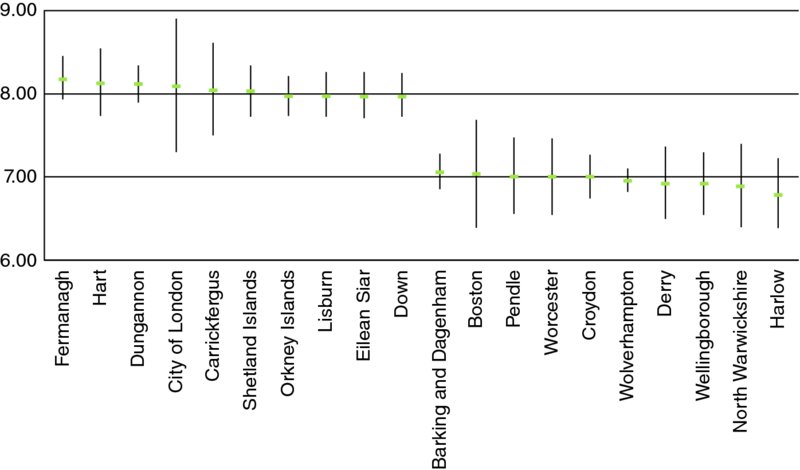

The APS data have already been analysed by ONS and others (e.g. Abdallah and Shah, 2012), including looking at subgroups of the population and making comparisons below the national level. As the sample grows, further detail will be available and will provide users with a large dataset to undertake further analysis. ONS publishes estimates at a more local level and for small subgroups of the population with more precision (e.g. ONS 2013). The latest data currently available are for 405 local areas across the United Kingdom. In Figure 7.2, we show the average life-satisfaction score, with confidence limits, in each of the 10 highest scoring and 10 lowest scoring areas for the 12 months April 2012 to March 2013. Some of the confidence limits are relatively wide, reflecting smaller numbers in the sample in those areas, and combining data from adjoining time periods will allow for greater precision. However, even data for 1 year allow for some clear discrimination between areas according to their average score on life satisfaction (though we would stress caution, and in particular that multiplicity be allowed for in any analysis).

Figure 7.2 Average life satisfaction 2012/13 (on 0–10 scale) in 10 highest- and 10 lowest-scoring local areas across the United Kingdom.

Date source: ONS, 2013.

One development triggered by the introduction of the ONS subjective wellbeing data has been for the Treasury, the UK Ministry of Finance, to update its ‘Green Book’ to include reference to using subjective wellbeing data in cost–benefit analyses (HM Treasury, 2011, p. 58). The Green Book is required reading for UK government officials assessing proposals for policies, programmes and projects, with the aim that ‘public funds are spent on activities that provide the greatest benefits to society, and that they are spent in the most efficient way’ (HM Treasury, 2011, page v). MNW staff are also working with government researchers to develop tools to evaluate the impact on subjective wellbeing that specific policies and publicly funded projects have made. However, the general ethos of the ONS is that it can only go so far in terms of linking their measurements to specific policies and programmes. The ONS data provide more of an overall picture and a backdrop against which policy officials are encouraged to build their evidence base. Policy officials are encouraged to add the same subjective wellbeing questions and more detailed ones to their own research surveys, and to draw on more policy-relevant indicators such as measures of poverty.

There is a slight tension here, at least during the early years of the MNW programme. The MNW programme seeks to establish standardised questions for assessing personal wellbeing and to encourage their use in many different surveys, beyond those conducted by the ONS. However, the ONS questions were described at least initially as experimental and potentially open to amendment in subsequent years. In practice this has not led to significant changes, so the use of the questions in other surveys is enabling a richer picture of wellbeing to be built up. One of the surveys adopting the ONS questions is the Cabinet Office's Community Life Survey across England. This is also designed to be comparable with an earlier set of citizenship surveys conducted by government, so that time series of some key variables in the social and community domain can carry on. The key themes of the new survey are social action (giving, civic participation), social capital (trust, influence) and wellbeing.

Although the subjective wellbeing questions were the new element of MNW from April 2011, it will be seen from Figure 7.1 that the MNW programme is about much more than subjective wellbeing in assessing national wellbeing and progress. Similarly, the ONS programme is not about the end of using GDP. Rather, this is a pluralistic approach to measurement, to provide measures for people with different interests and to encourage the use of a set of wider measures of national wellbeing and progress overall. Those interested in economic growth and those focussing on subjective wellbeing will find each of these measures within the ONS set, but the intention is to shift attention to the full set of wider measures of national wellbeing.

The Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi commission was undoubtedly a significant influence on the ONS programme. Much of the content of the commission's report was not new. However, the timing and the authority with which it was delivered helped ONS draw together and build on many existing developments across the commission's recommendations, recognising the boost that the commission had given to finding and using measures to supplement GDP. In Table 7.1, we give a flavour of how the MNW programme reaches all parts of the agenda set by the Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi recommendations. This is not to say that everything is close to being sorted: even within a well-developed and funded national statistical system, it will still take time for some of these developments to come to fruition.

Table 7.1 Examples of how the UK Measuring National Well-Being (MNW) programme addresses the Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi recommendations.

| Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi recommendations cover the following: | UK Measuring National Well-Being (MNW) programme includes the following: |

| Classical GDP issues

Household perspective; income and consumption (rather than production) and wealth; distribution of income, consumption and wealth; income measures of nonmarket activities |

|

| Quality of life

Improved measures of people's objective conditions and capabilities; comprehensive assessment of inequalities; survey data on quality-of-life domains; information to aggregate across quality-of-life dimensions, allowing different indexes; subjective wellbeing data |

|

| Sustainable developmentand environment

Dashboard of indicators of stocks; indicators of physical aspects of environment, especially proximity to dangerous levels of environmental damage |

|

Sources: Stiglitz et al. (2010) and ONS MNW programme outputs at: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/guide-method/user-guidance/well-being/publications/index.html.

We suggested in Chapter 6 that looking at stocks and capital, though challenging, might be a way of understanding national wellbeing overall. Here is a small selection of results from the MNW programme and associated outputs that we find interesting and indicative of what can be learned by focussing on stocks and capital:

- The United Kingdom's human capital stock (an estimated £17.1 trillion in 2010) is worth more than two and a half times the value of UK tangible assets – buildings, vehicles, plant and machinery and so on – as estimated in the national accounts for the beginning of that year;

- The richest 10% of households own 44% of the combined net wealth of all private households within Great Britain (total estimated at £10.3 trillion for 2008–2010);

- Approaching 13% of the area of the United Kingdom is taken up with its stock of forest and other wooded area (woodland stock was almost 3.1 million hectares in 2012);

- The proportion of adults reporting high levels of life satisfaction varied from 34% down to 15% across some 160 districts for which reliable data were available for 2012/13 (for the United Kingdom as a whole, almost 26% of adults reported life satisfaction levels of 9 or 10, on a scale of 0–10).

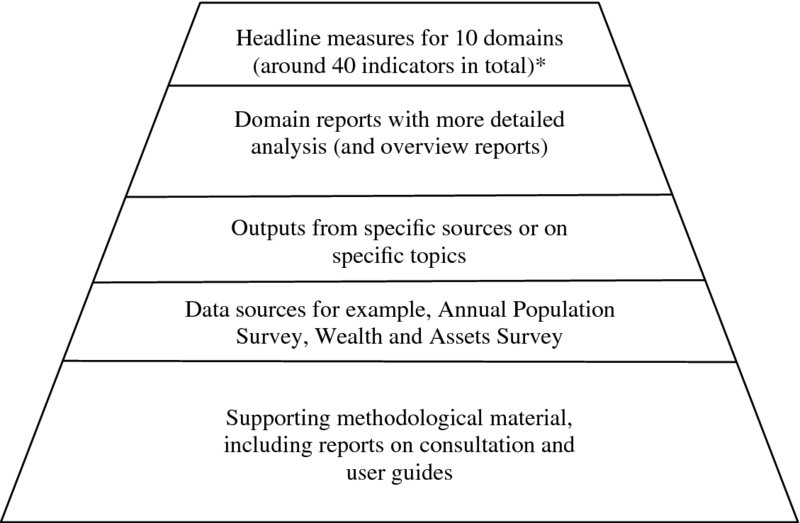

The ONS MNW programme is aimed at delivering information at different levels of detail, to meet user requirements for broader, headline measures as well as being able to drill down to more detail and to reach specific statistical source material, where users can undertake further analysis of the data. This is shown in Figure 7.3, which is not quite an ‘information pyramid’ because the ONS is not providing a single number to sit at the top of the pyramid.

Figure 7.3 The levels of information provided by the ONS MNW programme (this is not to scale!).

*With new ways of accessing statistics, for example, interactive wheel of measures, interactive graphs and maps.

The United Kingdom embarked on its MNW programme when, as is the case in several countries, there was already a set of sustainable development indicators (SDIs). The UK SDIs had been regularly published by official statisticians in the government department responsible for sustainable development policy (see Appendix for UK SDI website link and Section 15 in Chapter 2 for more on SDIs). Moreover, the SDIs had been developed nationally and internationally over the previous decade and had increasingly become presented as measures of national wellbeing and progress.

There had, for example, been a discussion meeting at the Royal Statistical Society in London in January 1998 billed as ‘Alternatives to economic statistics as indicators of national well-being’, where both of the papers (Levett, 1998, and Custance and Hillier, 1998) and all the discussion (Barnett et al., 1998) were about SDIs and the criteria for selecting indicators. The direction of travel was to move from economic statistics only to looking at economic, social and environmental indicators, but at least initially there appeared no conceptualisation of this as national wellbeing. Rather, the SDIs were presented as tools for developing sustainable development policy and for monitoring progress towards sustainable development: as Levett had noted at the 1998 meeting, ‘the development of sustainability indicators and policy are intimately intertwined’ (1998, p. 301).

This intertwining is inevitable as part of a policy process. When it works well, the statistics should be informed by an understanding of the policy they are meant to measure, and how they will be used. The role of official statisticians, whether in departments or a national statistics office, is to produce statistics for policy and for public use. However, it appears to us to be more complicated if statistics are needed primarily for policy, because there is a risk that policy needs might, even inadvertently, crowd out the use of the same statistics for public debate. The emphasis in the development of measures of national wellbeing and progress should be that they are meant for use as public statistics, including helping the electorate assess the performance of government, as well as in policy.

The need to protect and, better, to enhance the wellbeing of individuals has long been recognised as important in policy. Around 2007, the UK government department responsible for sustainable development worked with other government departments, the devolved administrations and other stakeholders to develop a common understanding of what wellbeing means in a policy context. It was intended to support those wishing to take a greater policy focus on wellbeing and to promote consistency. The common understanding is that:

‘Wellbeing is a positive physical, social and mental state; it is not just the absence of pain, discomfort and incapacity. It requires that basic needs are met, that individuals have a sense of purpose, that they feel able to achieve important personal goals and participate in society.

It is enhanced by conditions that include supportive personal relationships, strong and inclusive communities, good health, financial and personal security, rewarding employment, and a healthy and attractive environment.

Government's role is to enable people to have a fair access now and in the future to the social, economic and environmental resources needed to achieve wellbeing. An understanding of the effect of policies on the way people experience their lives is important for designing and prioritising them’. (Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs, 2007)

Alongside this, some measures of subjective wellbeing were included in the UK SDIs. The department responsible for sustainable development set about developing a new set of sustainable development indicators and consulted during 2012 on its proposals. The indicators were meant to complement the ONS measures of national wellbeing, an issue that had been spotted by, among others, a Parliamentary committee scrutinising work on environmental audit. Submitting evidence to that committee's inquiry into wellbeing, the Royal Statistical Society suggested that, while there may be some advantages in letting a number of flowers bloom, it might be more productive to bring the SDI and MNW developments together, ‘to work on a single measurement framework to meet a range of policy needs in a coherent and efficient way’ (Royal Statistical Society, 2013).

The Royal Statistical Society also noted that Scott (2012) had reviewed the potential conflict between improving wellbeing and sustainability as two central public policy goals of government. She pointed out that there is much common ground, especially through the focus each policy area has on broadly the same set of indicators. However, she is wary of ‘a simplistic win-win scenario of subjective wellbeing and sustainability’ (Scott, 2012, p. 168), arguing for a clearer, democratically derived, conceptual framework for policy makers regarding different wellbeing constructs. Nevertheless, it looks as if the two sets of United Kingdom measures, SDIs and MNW, will be brought together so that one overall measurement approach can be used for a variety of public policy needs.

The ONS held a conference in 2012 to mark the first 2 years of its MNW programme. Glenn Everett, the programme director, summarised how far the programme had progressed, with many outputs and the first new annual report on life in the United Kingdom. There was also much more to do. The domains and measures of national wellbeing were still under development and open for revision and further refinement. The subjective wellbeing questions were subject to further testing and possible development. There was also the issue of how to assess the progress of the United Kingdom from these measures: was it always clear whether, say, an increase in the value of a measure meant that the United Kingdom was making positive progress in that area? ONS promised to continue cooperation with international partners, including through the UN, OECD and EU, as well as further consultation and engagement within the United Kingdom.

Turning to the use of national wellbeing measures, the ONS remains keen to encourage more of this. It does look to us that more attention is being given to understanding the drivers of personal wellbeing than to those of national wellbeing. While not wanting to detract from analysis of personal wellbeing data, we are keen to see more use made of measures to determine national wellbeing and how, and why, that is changing. Policy linked to personal wellbeing is not new. We explored health and wellbeing, for example, in Chapter 2. There are opportunities for further policy areas to develop a national wellbeing focus, such as those being identified by the Legatum Institute Commission on Wellbeing Policy (see Appendix for website link). These could, for example, concern how major infrastructure projects, such as airports or high-speed rail networks, are considered against economic, social and environmental costs and benefits.

There continues to be a strong political narrative in the United Kingdom about the need for economic growth and deficit reduction. There is also some contesting of earlier ‘green’ agendas. It is in this political environment that ONS must remain strongly committed to producing wider measures of national wellbeing and progress, so that these are available to use alongside the regular data on economic growth and the public finances.

For a time, wellbeing had appeared in the stated purpose of UK government departments. For example, the 2008–2009 annual report and accounts of HM Treasury, the United Kingdom's Economics and Finance Ministry, recorded that one of its strategic objectives was ‘to ensure high and sustainable levels of economic growth, well-being and prosperity for all’ (HM Treasury, 2009, p. 11).

The new coalition government formed in the United Kingdom after the 2010 general election published a programme for government (HM Government, 2010) with three references to ‘well-being and quality of life’. Two of the references were about the importance of ‘a vibrant cultural, media and sporting sector’ (HM Government, 2010, p. 14) and of ‘a modern transport infrastructure’ (HM Government, 2010, p. 31). The third reference was to the ‘need to protect the environment for future generations, make our economy more environmentally sustainable, and improve our quality of life and well-being’ (HM Government, 2010, p. 17). This document did, therefore, recognise the broad agenda set by the Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi report and already taken up across the OECD and the EU. (At the time of writing, the United Kingdom is a member of both.)

However, the government also needed to set a number of priorities, largely shaped in the wake of the global financial crisis that began in 2007 and leaving the United Kingdom, and several more of the world's major economies, with structural deficits in their public finances. These priorities refer to economic growth rather than to wellbeing. By the time of a government report covering 2012–2013, the Treasury's objectives had been replaced by strategic priorities that include reference to ‘a growing economy that is more resilient’ and to reducing the structural deficit ‘in a fair and responsible way’ (HM Treasury, 2013, p. 9) but not explicitly to wellbeing. The only reference to wellbeing in the document is to the wellbeing of the staff of the Treasury (HM Treasury, 2013, p. 43).

Indeed, although we have not searched the strategy documents and business plans of every UK government department, it appears that the purposes and objectives of UK government departments most closely associated with wellbeing do not explicitly refer to it. A recent guide to the role and purpose ‘post-April 2013’ of the Department of Health does include many references to ‘wellbeing’, understandable in light of much national and international interest in improving health and wellbeing, though the overall role and purpose of the department is now described as ‘helping people live better for longer’ (Department of Health, 2013, p. 7). The language of the UK government is now predominantly about sustainable growth and sustainable development, along with a fair and equal Britain, rather than wellbeing.

Within the United Kingdom, there are currently two countries in which many governmental functions are devolved by the UK government. In both countries, the main policy focus is on sustainable economic growth. There is a flavour of wellbeing in the aim of the devolved government for Wales, which is ‘working to help improve the lives of people in Wales and make our nation a better place in which to live and work’ (see Appendix for website link). The devolved government for Scotland is similarly responsible for most of the issues of day-to-day concern to the people of Scotland, including health, education, justice, rural affairs and transport. The declared purpose of the Scottish government is this: ‘To focus government and public services on creating a more successful country, with opportunities for all of Scotland to flourish, through increasing sustainable economic growth’ (see Appendix for link). The word ‘flourish’ resonates with the eudemonic perspective on personal psychological wellbeing that we discussed earlier. In both Wales and Scotland, there are developments to measure national wellbeing and progress (see Appendix for links). In Wales, this covers wellbeing and sustainable development. ‘Scotland Performs’ measures and reports on progress of government in Scotland.

In drawing on high-level government documents, we are aware that we are not necessarily presenting a comprehensive picture of wellbeing policy in the United Kingdom. This is for two main reasons. First, underneath the strategy statements much work goes on across government to deliver specific policies, programmes, projects and services. Here there may well be examples of wellbeing being taken into account. We also discussed in Chapter 2 that there is a legal basis for some public authorities to have regard to economic, social and environmental wellbeing when letting contracts for goods and services. There does not yet appear to be any monitoring of the extent and the effectiveness of this legislation, so this would be an interesting area of future research. It would be unusual if some form of interdepartmental committee was not starting to share good practice and help build a wellbeing policy community of interest. Allin (2014, p. 438) drew on informal discussions to form a view of the kinds of areas in which officials were looking at policy through a ‘wellbeing lens’. These were childhood obesity, community grants, offending reduction and personal budgets for public service users. The field of wellbeing at work appeared to be another policy area to focus on (Allin, 2014, p. 450).

We are confident that there will be considerable interest in the research community to review how wellbeing data are being applied to policymaking. This should be stimulated by the work of the Legatum Institute Commission on Wellbeing Policy mentioned earlier in this chapter, which is exploring how wellbeing analysis can be usefully applied to policy and will presumably be publicising exemplars of wellbeing policy. The commission is chaired by former Cabinet Secretary Lord O'Donnell and it promises that its reports will illustrate the strengths and limitations of wellbeing analysis and provide original and authoritative guidance on the implications for public policy.

The second reason we may have painted a less than complete picture of wellbeing policy is that we have not examined the extent to which policymakers are drawing on, or are at least aware of, the considerable volume of evidence and measurement tools provided by academic and other nongovernmental centres. There is a significant issue of knowledge transfer here, to facilitate the flow of information from policy makers on the policy areas needing development and the flow of knowledge from researchers with evidence and techniques that could usefully be brought into the policy world. The world has moved on since data about the state of Britain's economy, society and environment were summarised in the annual volume of Social Trends, which policymakers might (or might not) have consulted. One major way of encouraging knowledge transfer is to build a requirement for this into funding arrangement for academic research. The Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) has, for example, identified wellbeing as a priority area in making the case for the social sciences, and the ESRC website (see Appendix) contains many ‘evidence briefings’ and other reports relating to wellbeing. The publication by Brown et al. (2009) is one example of such knowledge transfer in action in the field of wellbeing and working life.

Allin (2014, p. 422) notes that ‘the United Kingdom enjoys a strong network of civil society organizations, universities, and think tanks with a real expertise in wellbeing and this has helped to enrich the political and policy debate considerably’. We have experienced this in action, especially through the meetings of the Technical Advisory Group for the ONS's MNW programme. Many UK centres play a strong role internationally, and have done so for many years. This brings challenges where, for example, methodologies have been developed but which are not fully consistent with later initiatives. However, the benefits of having a strong network to work with have proved to be considerable. We have included links to UK centres in the Appendix.

The machinery of government can move at what might seem at times a frustratingly slow pace. The announcement by the British Prime Minister in November 2010 signalled one immediate policy shift, to start measuring wellbeing. Some government policies were, of course, already engaged with wellbeing, particularly to link health with wellbeing, but in other areas progress is not so easy to spot. Although wellbeing is less in the headlines, there are a number of building blocks being put in place to support wellbeing in policy. We have mentioned the ‘Green Book’, public value in procurement and the Legatum Institute Commission, for example.

Bache and Reardon (2013, p. 14) have reviewed the emergence of wellbeing as a political concept in the UK government. They conclude that a paradigm shift in measurement may be taking place, especially through the ONS MNW programme, and that the wellbeing ‘remains on the government agenda’. However, they also conclude that more action is required by those who support and sponsor policy inside government if ‘more decisive [well-being] policy action is to follow. In short, a more effective coupling of the problem stream to policy and politics streams is needed for us to claim with confidence that well-being is “an idea whose time has come”’. As Bache also observes elsewhere that it is wellbeing measurement that is developing more than policy at the EU level (Bache, 2013, p. 35), we feel it is time for us to leave the United Kingdom as our case study and draw our thoughts to a conclusion in the following chapter.

References

- Abdallah S. and Shah S. (2012) Well-being Patterns Uncovered: An Analysis of UK Data. New Economics Foundation, London.

- Allin P. (2014) Measuring wellbeing in modern societies. In: P.Y. Chen and C.L. Cooper (eds) Work and Wellbeing: Wellbeing: A Complete Reference Guide, vol. III. John Wiley & Sons, New York, pp. 409–465.

- Bache I. (2013) Measuring quality of life for public policy: an idea whose time has come? Agenda-setting dynamics in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 20(1), 21–38.

- Bache I. and Reardon L. (2013) An idea whose time has come? Explaining the rise of well-being in British politics, Political Studies. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1467-9248.12001/abstract;jsessionid=80F08AF389E4380B8EB4429346B756B5.d03t02.

- Barnett V. et al. (1998) Discussion at the meeting on ‘Alternatives to economic statistics as indicators of national well-being’. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A, 161(3), 303–311.

- Beaumont J. (2011) Measuring National Well-being, Discussion Paper on Domains and Measures, UK Office for National Statistics, http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/wellbeing/measuring-national-well- being/discussion-paper-on-domains-and-measures/measuring-national-well-being—discussion-pap er-on-domains-and-measures.html.

- Brown A., Casey B., Charlwood A. et al. (2009) Well-being and Working Life: Towards an Evidence-Based Policy Agenda. ESRC Seminar Series, Mapping the public policy landscape, Economic and Social Research Council, Swindon.

- Cameron D. (2010a) The next age of government. http://www.ted.com/talks/david_cameron.html (accessed 17 October 2013).

- Cameron D. (2010b) PM's speech on creating a ‘new economic dynamism’ at https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pms-speech-on-creating-a-new-economic-dynamism (accessed 17 October 2013).

- Cameron D. (2010c) PM's speech on wellbeing at https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-speech-on-wellbeing (accessed 17 October 2013).

- CSO (1970) Social Trends 1, Central Statistical Office, Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London.

- Custance J. and Hillier H. (1998) Statistical issues in developing indicators of sustainable development. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A, 161(3), 281–290.

- Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs (2007) A Common Understanding of Wellbeing for Policy Makers at http://archive.defra.gov.uk/sustainable/government/what/priority/wellbeing/common-understanding.htm (accessed 24 October 2013).

- Department of Health (2013) Helping people live better for longer: A guide to the Department of Health's role and purpose post-April 2013. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/226838/DH_Brochure_WEB.pdf (accessed 24 October 2013).

- Dolan P. and Kavetsos G. (2012) Happy talk: mode of administration effects on subjective well-being. CEP discussion paper, no. 1159. London School of Economics and Political Science at http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/45273/.

- Dolan P., Layard R. and Metcalfe R. (2011) Measuring subjective wellbeing for public policy: recommendations on measures. Special Paper No. 23, March 2011, Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics.

- Hall J., Giovannini E., Morrone A. and Ranuzzi G. (2010) A Framework to Measure the Progress of Societies, OECD Statistics Directorate Working Paper No. 34, STD/DOC(2010)5, http://search.oecd.org/officialdocuments/displaydocumentpdf/?cote=std/doc(2010)5&docLanguage=En.

- Hicks S. (2011) Spotlight On: Subjective Well-being, Office for National Statistics. Available at http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/social-trends-rd/social-trends/spotlight-on-subjective-well-being/inde x.html.

- Hicks S., Tinkler L. and Allin P. (2013) Measuring subjective well-being and its potential role in policy: perspectives from the UK office for national statistics. Social Indicators Research, 114, 73–86, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0384-x.

- HM Government (2010) The Coalition: Our Programme for Government. Cabinet Office, London, available at https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/78977/coalition_programme_for_government.pdf (accessed 24 October 2013).

- HM Treasury (2009) Annual Report and Accounts 2008–09. The Stationery Office, London. Available at http://www.official-documents.gov.uk/document/hc0809/hc06/0611/0611.pdf (accessed 24 October 2013).

- HM Treasury (2011) The Green Book: Appraisal and Evaluation in Central Government. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-green-book-appraisal-and-evaluation-in-central-governent (accessed 23 October 2013).

- HM Treasury (2013) Annual Report and Accounts 2012–13. The Stationery Office, London. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/212752/hmtreasury_annual_report_and_accounts_201213.pdf (accessed 24 October 2013).

- Huppert F.A. and So T.T.C. (2013) Flourishing across Europe: application of a new conceptual framework for defining well-being. Social Indicators Research, 110, 837–861.

- Levett R. (1998) Sustainability indicators in integrating quality of life and environmental protection. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A, 161(3), 291–302.

- Moser Sir C. (2000) Foreword in Social Trends 30, Office for National Statistics, London.

- NEF (2011) Measuring Our Progress: The Power of Well-Being. http://dnwssx4l7gl7s.cloudfront.net/nefoundation/default/page/-/files/Measuring_our_Progress.pdf (accessed 2nd August 2013).

- OECD (2013a) How's Life? 2013: Measuring Well-being. OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264201392-en (accessed 2 December 2013).

- OECD (2013b) OECD Guidelines on Measuring Subjective Well-Being. OECD Publishing.

- ONS (2011a) Measuring What Matters: National Statistician's Reflections on the National Debate on Measuring National Well-being. UK Office for National Statistics. Available at http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/guide-method/user-guidance/well-being/publications/index.html (accessed 24 July 2013).

- ONS (2011b) Initial Investigation into Subjective Well-being Data from the ONS Opinions Survey. UK Office for National Statistics. Available at: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/guide-method/user-guidance/well-being/publications/index.html.

- ONS (2012a) Initial Findings from the Consultation on Proposed Domains and Measures of National Well-being, Office for National Statistics. Available at: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/guide-method/user-guidance/well-being/publications/index.html.

- ONS (2012b) Analysis of Experimental Subjective Well-being Data from the Annual Population Survey, April–September 2011. UK Office for National Statistics. Available at: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/guide-method/user-guidance/well-being/publications/index.html.

- ONS (2013) Personal Well-being across the UK, 2012/13. Office for National Statistics. Available at: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/wellbeing/measuring-national-well-being/personal-well-being-across-the-uk--2012-13/sb—personal-well-being-across-the-uk--2012-13.html.

- Royal Statistical Society (2013) Memorandum to the Environmental Audit Committee Inquiry on Well-being at http://data.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/WrittenEvidence.svc/EvidencePdf/1005 (accessed 24 October 2013).

- Scott K. (2012) Measuring Wellbeing: Towards Sustainability? Routledge, Abingdon.

- Spence A., Powell M. and Self A. (2011) Developing a Framework for Understanding and Measuring National Well-being, Office for National Statistics at http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/guide-method/user-guidance/well-being/publications/previous-publications/index.html (accessed 17 October 2013).

- Stiglitz J.E., Sen S. and Fitoussi J-P. (2010) Mismeasuring Our Lives: Why GDP Doesn't Add Up. The New Press, New York.

- Tinkler L. and Hicks S. (2011) Measuring Subjective Well-being. Supplementary paper to the National Statistician's Reflections on the National Debate on Measuring National Well-being, at http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/guide-method/user-guidance/well-being/publications/previous-publications/index.html (accessed 13 September 2013).