Chapter 4

Pursue Joy by Thwarting Injustice: Develop Teacher Agency Through Reflective Practice and Collaboration

As a newer teacher in the early 2000s, I wouldn't have predicted just how deeply I would dive into the ecosystem of school over the next 15 years, how much I would delight in collaborating with other teachers and families, and how career sustaining I would find curriculum‐making to be. Certainly a major ingredient in the movement toward student centeredness and teacher agency is the love educators like myself and so many others have put forth in reclaiming their intellectualism and curriculum‐making as part of our profession.

However, within that love, teacher intellectualism, and robust curriculum‐making lay major tensions in terms of how various leaders, families, and even educators themselves perceive the role of teacher in a school community.

In the first section of the book, we talked about how important it is for educators to engage in seeing and feeling the pressure of injustice to be an agent of joy and justice within their school community.

In this next section, we will practice unpacking some of those tensions that lay within the questions: What is the role of a teacher in terms of what they should teach and how students in their classrooms should learn? How can teachers reclaim their role through reflective practice? How does joy live within this pursuit?

2006

In the mid‐2000s, New York City, along with a few other major urban centers in the United States, had robust campaigns calling twenty‐somethings and other career‐changers into their chronically sparse teaching forces. These campaigns were everywhere: digital posters plastered AOL message boards, and analog posters slathered college campuses, beckoning folx from all facets of life with four‐year degrees to “fill a critical need” and to “share knowledge and experience with youth!” In turn for teaching in said urban centers, these alternate routes to teaching certification paid for your graduate tuition and helped you along the road to getting your teaching licensure through the state. The catch: schools were located in far‐out neighborhoods, special education and science were the only teaching licenses for your choosing, and you had to teach full time while earning your degree and license.

When I began my graduate studies in education to pursue teaching kids, the concentration in which my license was earned wasn't so important to me. I had just spent the last two years of my life living on the South Side of Chicago, witnessing the types of injustice that many white and other privileged people only read about. I had learned, or maybe more accurately put, I had become aware of the vast gaps in my brain and in my body re: knowing anything about urban education, and had begun to develop a keen understanding of how essential community and connection were in the realm of searching for hope and humanity within the context of schools that had been named “failing.”

The only thing I knew for sure was that I wanted to work with kids in schools, that it was absolutely necessary for me to learn how to be in community with their families and my future colleagues, and that I did not want be in debt over $50,000 for a career that was far, far away from that sort of financial return. It made perfect sense to me to accept whatever position in whatever school with whichever group of kids through the New York City Teaching Fellows (NYCTF).

I applied to, and was invited into, the NYCTF group‐to‐individual interview process a few weeks later. At the time, my salary, working in an educational nonprofit housed at the University of Chicago, was meager; in short, I was poor. My financial status served me rich self‐sustenance; two buses and a train? No problem, free sight‐seeing. A 20‐pound bag of groceries and a two‐mile walk? No problem, free gym time. Four weeks for the used textbook to come? Got it, I had been meaning to renew my library card anyway. So a trip from Chicago to New York City with less than $250 to my name was simply another string of logistical challenges to be worked out.

For $224, I flew to New York City from Chicago, headed straight to the Barnes and Noble located on 17th street in Union Square, practiced my teaching lesson, whispering to myself, near the YA books (I remember my lesson involving something about M&Ms and counting … it was very rudimentary), and did the four‐hour interview process at Washington Irving High School just a few blocks away. My “lodging” for the evening included a jaunt in the West Village for a post‐interview after party. Late into the night, I headed back to La Guardia Airport, slept for a few hours in the airport, and was back in Hyde Park for another day of work schlepping along the route of schools I worked with as a tutoring program supervisor.

Memories of my first six weeks preparing to be a teacher are very fuzzy. I was at Brooklyn College, there was a lot of chatter around learning disabilities, and most of my time was spent commuting between Penn Station and Flatbush, Brooklyn, and to Jamaica, Queens, and back, daily.

I used to think my first day of teaching in Brooklyn was in September 2006, but it was actually June 2006, during my summer school placement (counting as my first in‐service teaching hours) at a giant fortress of a school in Jamaica, Queens, which is no longer open. From my studio sublet in Chelsea, I had to get up at 4:00 a.m. to make it to this giant school in Queens by 7:45 a.m. Of the 36 children enrolled in class, about eight showed up regularly. It was some sort of social studies make up credit class. The teacher was animated, but she barely acknowledged my presence. I wasn't really sure what to do, so I mostly observed and took notes verbatim. This was my preparation, New York State told me, for teacherhood.

My undergrad credentials didn't reflect enough math and science credits to work toward teaching science in any official capacity, so I was earmarked for a teaching certification that no longer exists: Transitional B Certification for Middle Childhood Special Education Grades 5 through 9. Ironically, my very first “official” teaching placement, in Brooklyn, was in a … wait for it … 12:1:1 special education science class to a group of eleventh and twelfth graders, who ranged from age 16 to 21.

My first day of full‐time teaching in Brooklyn was illuminating for me, while completely predictable for my students. I was a 23‐year‐old white woman teaching a group of Latine kids and Afro‐Caribbean Black kids, two to three years my junior, who found me amusing at best, irrelevant at worst. At one point in time, I was compared to the chef in the film Ratatouille. Another time, a game of dice erupted in the corner of my classroom and dollar bills were most definitely exchanged. Had my first days of teaching inadvertently turned into a summer block party?

In this 12:1:1 self‐contained special education science class, the young people and I existed in one of the most restrictive classroom environments in a community school. I had never taught a day in my life, and yet here I was, given full jurisdiction over a group of people who were two to three years my junior. The school had yet to finish a round of painting and cleaning by the time the first day of school rolled around, so I spent the first two days of my teaching life in the auditorium, followed by an extended lunch and a really long recess in the school yard.

My roster was not official yet, but other special educators who had been working at the school had the students' backs. They made up a sort of schedule/agenda for us, and we mostly survived.

It was on the second day of school that I understood I would be a science teacher: for the eleventh/twelfth grade self‐contained bridge class, in addition to the ninth grade Integrated Co‐Teaching1 (ICT) life science class, and the tenth grade ICT Earth science class. Because I was working with ninth grade and tenth grade teachers who were actually certified in the teaching of science, I sailed along in those classes, finding spots of momentum in developing projects that were somewhat UDL‐2 esque and accommodating to the many, many kids who were otherwise disinterested. But for that eleventh/twelfth grade class … I was on my own.

I asked the special education department chair if there was a particular curriculum I should follow, or perhaps a textbook the students should have. I remember looking back at her, and understanding what her glance and her sigh communicated that her words couldn't, or didn't have the energy or heart to tell me: there was no curriculum to follow for an eleventh/twelfth grade group of students who weren't interested in reading, for a teacher to follow who had only high school science and a brief overview of chemistry and biology in her undergraduate days.

So then, I began to lean on a different sort of curriculum‐making journey: one that was messy, one that was riddled with mistakes; but also one that was student‐centered and communal. My curriculum‐making journey eventually found its way toward a sound research base, and it greatly impacted my growth and my students' growth, both academically and personally. In the following parts of this chapter, we'll unpack that journey starting with points of reflection not just in my teaching, but, more importantly, in yours!

Points of Reflection

When I work with fledgling teachers at the university level, one point of reflection I leave them with at the end of the semester is to write a letter to their future selves; the teacher they hope to become and the teacher they think they will be (Figure 4.1).

FIGURE 4.1 Letters to Your Future Self, featuring the work of undergraduate students in my integrated literacy methodologies class at Brooklyn College in the Department of Childhood, Bilingual, and Special Education: Adrianne Payne, Mandy Liang, Sarah Peter, Victoria Chen‐Fan, Shaima Elsayed, and Iris Ofray (2021).

In this reflective space, I find myself in conversation with my past self, almost as if I am in Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol, with the current version of myself taking up the role of the Ghost of Christmas Past, but replace Christmas with teaching and London with Brooklyn.

In the first scene, I envision my older, seasoned self encountering my younger self: twenty‐something, semi‐shell shocked new teacher Kass surrounded by students who were used to their teachers failing them. I'm ill‐equipped with useless tools like outdated textbooks with their matching prescribed curricula that were completely unsuitable for the teaching and learning experiences my students and I longed for.

My old self wants to hug and nourish young Kass, give an it's okay to slow down pep talk, and bring something life‐giving, like a gigantic sandwich and big bottle of water to compensate for the meager yogurt and donut lunches of yesteryear; and, more importantly, the exhaustion that surfaced from the trial and error and classroom chaos that threaded my first years of teaching together.

In the second scene, I go back to the vignette I started earlier in this chapter, the part where I began my curriculum‐making journey. Borne out of necessity, it started with listening to and observing the students I taught. I remember it was the young people in my classroom who were both my toughest critics and greatest teachers.

For example, my old ghost self‐ushers this young Kass toward the joy (and the jokes!) that came with resurrecting parts of Al Gore's An Inconvenient Truth and my attempt to create a “fun” text pairing with film shorts from Dr. Seuss's3 The Lorax. The students in my class erupted in laughter as soon as the ridiculous striped forest from The Lorax showed up on the TV screen! I suppose I thought showing 17‐year‐olds Dr. Seuss cartoons was a legit form of instruction in their environmental science class because of my fabulous teacher preparation during my six weeks spent “learning how to teach” during summer school. The students I taught never let me hear the end of those terrible curricular decisions.

But their laughter and their jokes helped me learn that more than anything, I needed to create meaningful learning activities that were linked to their lived experience, their learning needs, and the learning standards.

Later that same year, I remember extensive research on food deserts, field trips to the grocery store, significant meal planning, and even meal sharing with one another. Those curricular experiences were cocreated between me, the students I taught, and some of their families. In short, it was relevant, and it was also a curriculum that was connected to Living Science.

And finally, I visit the harder scenes with my young self. As I see this past, my whole body winces and my stomach turns. However, these are the moments that are especially important to share, because despite what the Educational Industrial Complex (see sidebar) tells you, nobody is infallible.

I remember all the times I just pushed through class so it would be over, ignoring students' needs and centering on my own instead. I remember all the times I called the dean because students refused to take their hats off. I remember attempting to create a reading intervention experience for a group of tenth graders without really planning or understanding the foundational literacy of what I was trying to do, and how ridiculous the group of students thought the whole ordeal was, how ridiculous they thought I was. I remember how I used to participate in a school‐wide mandate that sent students home because they weren't wearing their uniforms properly.

I'm taking deep breaths now … there were parts of those years that were terrible for me, yes, but even more so for those students who were the recipients of my errors.

So yes, there are a lot of gifts I wish I could grant to my new teacher self that would have made things less terrible, more joyful, more just. For example, I wish I had understood the power of community that comes with making time for enduring conversations with students while class is in session. I wish I had a better teacher preparation experiences to build more impactful foundational literacy and numeracy skills with my students. And more than anything, I wish I would have been more present, less focused on paying bills and finishing grad school assignments.

Had I been equipped with those gifts earlier in my career, I'm sure my school life, along with my students', would have been quite different. Perhaps I would have been more present, more slept … more prepared.

But this is the part of the Dickensian story where all the reflection pauses, and the characters are left with only their present: that's me, that's you, it's us, and it is our now.

It is in the collective journey where you find the answers. A fancy, more academic term for this work I'm suggesting is long‐term locally derived inquiry. That is the story of my teaching career, it is the path I've not veered far from, and it is the justice work I am suggesting now. Here is what I mean.

As is with all learning, the deepest kind is one that is curiosity‐based and human‐centered, where those seeking the information are the most instrumental parts of the knowledge‐making journey.

This is where individuals ask questions about the needs of the people they are in community with, note what they don't know and what they need to learn, and, together, they work to explore, find, and try various experiences, texts, and learning activities that fulfill the needs that were identified originally.

Needs evolve and time continues, and the community works together to evolve as such.

So, as much as I would have loved to enter years one and two and three in my classroom teaching life just knowing, I very much understand I wouldn't be who I am today had I not experienced the trials and errors along the way. However, I do know that both me and my students would have been much better off had I been granted more time to collaborate and think with my colleagues, or reflect on what I was learning in grad school to build curriculum with my school community more deeply and clearly in ways that were more deeply impactful for the student community.

Within those first years of teaching, I'm not sure having “known” would have been as well‐received had I not discovered them through my own questions along with students' experiences and my colleagues' care. I firmly believe one cannot enter into a community of people—whether they are very new or very experienced—and simply know what that community needs. Time spent with people you are put in a position to teach matters.

The Nature of a Curriculum‐Making Journey

Curricular path.

Herein lies the just nature of a curriculum‐making journey, a primary component of an educator's justice work:

- We do the inner work of understanding who we are, where we've been, and what it is we're trying to do. In other words, we develop a more powerfully reflective practice.

- We prepare ourselves by doing the study and practice piece of teacher preparation that helps us understand how to teach, developing a strong base of knowledge that underscores brain‐based learning, culturally responsive pedagogy, and developmentally appropriate foundational literacy and numeracy skills.

- We work to deeply understand the communities in which we work; that is who we are teaching and what we are teaching.

- We care for ourselves, and we care for our community.

First, let's continue our curriculum‐making journey by developing a more ritualized reflective practice.

This is the reflective component that is woven through the text. While it is absolutely a series of intentional exercises, reflection works most powerfully when it is practiced habitually. It is also essential that we consider the development of agency for individuals within the field of teaching. Many of the reflective exercises we've worked through thus far in the text have called us to dig through past school experiences, including:

- Journaling about our experiences as students in the early years of our schooling.

- Thinking about the beginning years of our teaching careers (like we did earlier in this chapter).

- Considering the legacy of different laws and policies on different groups of people throughout the history of schooling.

Daily reflective practice looks different. This is the ritualized reflection we build into our lived experiences each morning or afternoon or night. The time in which ritualized reflection happens is not so important. Whether you choose to reflect independently or within a group is not so important either.

What's important is that you make space in your mind to think about your decisions and actions in connection to the community you teach and learn with, both honestly and consistently. This ritualized reflection helps to ensure you are in alignment with your community's needs and that you are moving toward shared learning goals like state standards, tiered objectives, and/or IEP goals.

Collaborate: Build Your Reflective Practice, Together

The following practices and rituals demonstrate ways to do this work in collaboration with other stakeholders in your school community.

Create Consistent Spaces for Reflection: Schedule Time with Colleagues That You Look Forward to (Like Lunch!)

There were, and still are, quite a few reflection rituals that make a tremendous difference in my teaching and learning life. Some of the deepest connections I've made with other humans happened during shared lunches with other teachers on my grade team.

When I was teaching elementary school in my later years of classroom life, I came to know this space as the most authentic one for my development—both personally and professionally. Every Thursday, a teacher who had been teaching for 20‐plus years hosted lunch in the classroom she shared with her co‐teacher, a newer teacher who brought great energy, curiosity, and humor to our shared table.

In this space, members of our fourth grade team would rotate in and out each week of the open invitation, always with at least four to five people present. Here, in conjunction with sharing interesting snacks and trading recipes, we asked each other questions we didn't necessarily feel comfortable surfacing in front of the entire teaching staff (we were in a group of approximately 100 teachers serving nearly 1,000 students!). Together, we learned skills and strategies that were more emergent and directly connected to our student community.

For example, I remember working through a new math curriculum with lots of “rich tasks” that were new to many of us. For some of us, the lessons would go terribly. We reported to our colleagues about students rolling around on the rug, or the students who would show expressions that mirrored our confused teaching.

I remember telling my colleagues how the new lessons “went” in terms of what I thought students left understanding (not a whole lot … was it possible that they left the math lesson at a deeper state of confusion than in which they started??). I'd ask how their students responded to similar work, or how they worked through the same problem set or task.

My colleagues' feedback was candid because after meeting every week for months (and, for some of us, years as we had been at the same school and grade team for quite some time), we trusted one another. This honesty came from the alchemy of teachers' genuine yearning to be better at their craft mixed with authentic sharing from people who worked toward similar goals.

We all wanted the student community to have better, more joyful, and more impactful learning experiences. We were all deeply interested in creating stronger pedagogy where students became more proficient in their foundational math, literacy, and critical thinking skills while staying true to their identities along the way.

Establish Routines and Rituals with Colleagues: Purposefully Work Toward Shared Vision and Illuminate Individual Strengths

Another powerful component of reflective practice I developed throughout my teacherhood was the ability to develop a shared vision with my co‐teachers. This manifested through a series of ritualistic daily check‐ins, weekly planning sessions, and even frequently attended happy hours! Throughout my teaching career, the relationships I've developed in the many classroom spaces is one of the most important markers of my pedagogy. The camaraderie and fellowship that my fellow teachers and I cultivated had a profound impact on the families and students we served. It also changed our ability to sustain and grow the kinds of goals we had for our teaching and learning lives.

This work does not happen automatically, and it is different than a teaching friendship. Cultivated camaraderie and shared vision grows from intentional and meaningful planning from teachers who share a school community. It doesn't happen overnight, nor does it just happen when teachers share a hallway together or sit next to each other at staff meetings.

This is where rituals and routines come in: they are a key element for developing a collaborative reflective practice. For example, in the teacher groups I have worked in, we used a variety of protocols to surface our personal needs, cultural orientation, and values. As we got to know each other and our students, we spent time cocreating shared visions for our classroom communities, including individual strengths and students' interests. Additionally, we took great interest in developing our place‐based pedagogy and how the world was positioned around us.

Our vision for our classroom was cocreated with our students and their families as well.

The rituals and routines we established allowed for us to not only work toward shared understanding, but also to name what wasn't going well, concerning practices, and/or parts of a lesson that triggered pain points for individuals or groups of people. Below are suggested steps that support building a more collaborative reflective practice and establishing routines and rituals.

- Determine in which context you'll be collaborating. This could be within a grade team, a subject‐area department team, or perhaps in a smaller context such as a partnership within a co‐teaching environment. Maybe it's just a friend who you enjoy working with who shares the same students, or students who are similar to those in your class/es. Whomever you choose to collaborate with, they should be a person or people who you are working with in a similar school or the same school community. You should also be able to schedule meetings with them regularly (preferably baked into your teaching schedule already!).

- Agree to document some reflective experiences beforehand. For example, before you begin spending any kind of significant time together, spend time doing inner work by developing an identity map and/or zooming in on a few moments within your personal school history timeline (see Historical Underpinnings section online). While it will not be necessary to share your reflective artifacts fully during your first few meetings, it will be important to have the foundational mindset of who you are in place. The inner work of identity mapping and timeline pedagogy in the context of personal history of school allows you to consider your identity markers and how they matter in your teaching and learning life.

- Schedule a first meeting during which you state your beliefs and values for the work you do. See the lesson plan in Chapter 3 for surfacing needs and values, which is the perfect protocol to do this work.

Another example of this work is featured below: documenting a team's Values‐Practice Connection by sharing anecdotes that demonstrate their foundational values. There, you will find examples of story snippets that match the values of a team during one of their initial collaborative reflective sessions.

The Values‐Practice Connection

This team began with the short, poignant question that defines an educator's everything in terms of how they operate in school communities: “What are your values?”. This team surfaced their values through story, strengthening their core collective belief system within their community. The Center for Nonviolent Communication has an excellent resource to support people in naming their values available on their website, called the “Needs Inventory”.

Later, each individual worked to clarify their values in alignment to their practice (as a verb!), especially when working toward the shared goals of the team's community. In Table 4.1, find the shared value set created during this period of time. We call this the Values‐Practice Connection.

TABLE 4.1 Values‐Practice Connection examples.

| Values | Practice |

|---|---|

| Sportsmanship |

|

| Love |

|

| Authenticity |

|

| Communication |

|

Move Away from Static Meeting Agendas: Complicating What We Mean When We Say “The Work”

Embracing multiliteracies like talk story is an important component of teaching and learning methodology, especially through the lens of engagement. In many classrooms, administrative meetings, and other professional learning experiences, the idea of “chit‐chatting” or passing along stories orally is seen as separate from “the real work,” the Work with a capital “W.” As I've grown my own pedagogy in partnership with many students, teachers, and families over the years, I've had lots of opportunities to witness how both low stakes (e.g., a description of what one ate for breakfast) and high stakes (e.g., a description of a conflict one personally experienced in school) oral storytelling takes a powerful role in shaping learners' growth.

As a teacher who has grappled with, explored, and taught through multiple forms of literacy experiences, I'd heard of and practiced oral history projects with students. We learned about folktales and griots. Even as a kid, when I sat around the campfire (literally) and listened to my family tell ghost stories, I walked away a changed person.

To this day, with each community of learners I have worked with as a classroom teacher, whether they were in my elementary school classroom, high school advisory, or graduate class sitting with me at Teachers College, we built community circle time together to share parts of our stories.

Sometimes, the sharing would be something basic, like what students were looking forward to in the week. Other times, it would be something more emotive, like an appreciation about a specific peer. There were also times when the sharing was more restorative, like when members of the class experienced a problem or crisis together.

It wasn't until I started working with two different groups in a professional context that I learned just how powerful and important talk story is to a group's ability to grow and learn from one another. First, my partner, Cornelius, and I have worked with a wide network of teachers in Kapolei, Hawai'i, to support them in building their literacy practices. Second, I worked with a group called Breaths Together for Change (mentioned in Chapter 1) with the goal of ending racism through white racial reckoning.

While I could go on for a very long time about the potency of my learning in each context, my goal here is to underscore what those two groups had in common that lent themselves to not necessarily just my own personal growth, but, more importantly, the connectivity within the group and a stronger version of collective purpose.

To talk story, or mo'olelo in Hawai'i, is to pass wisdom through the spoken word. It is a pidgin phrase that comes from the ‘Ōlelo language, a tradition that comes from an Indigenous knowledge‐base, and, to this day, is part of the daily life in Hawai'i and other Pacific Islands.

Rosa Say, author of Managing with Aloha, describes the concept of talk story:

Our Hawaiian ancestors did not pen a written history of our islands. Information was passed generation to generation orally, with the ‘Ōlelo (the language and spoken word) and in storytelling. Today there is much effort in our Hawaiian renaissance to record what we know about our past history before the kūpuna (our elders) forget and can no longer tell it to us. Still today, for us to communicate and dialogue is to “talk story.” There is so very much I personally have learned from the ‘Ōlelo form of teaching, perhaps most of all that anyone who speaks has the potential to be my teacher. I only need listen as well as I can, quieting the voices in my own head (Say and Fiske 2019).

My favorite part of Rosa Say's description of talk story is the part when she says that anyone who speaks has the potential to be her teacher, so long as she is able to listen. Talk story offers us an important frame to situate ourselves when we sit down to learn in the educational spaces we work within.

In Breaths Together for Change, each meeting was centered around participants' personal stories in connection to meditations we listened to. In the Hawai'i educator group Cornelius and I facilitated in partnership with educators from the community, we adopted a similar approach that was heavily influenced by mo‘olelo, or talk story, as modeled by our Hawai'i education partners.

In any group I have led or been a part of, the creation of space for the telling of stories served as impetus for not just change, but also for the hope of creating something better. Creating space for the telling of our stories is a proclamation of joy, and while storytelling might feel like a subversive thing to do in a professional learning experience (and maybe in some places or institutions it is), it as an important step toward learning that impacts communities on both personal and professional levels.

The Six‐Word Story

Not everybody will feel comfortable with sharing their stories. Some might even think it inappropriate in the workspace. If you aren't sure how storytelling will be received in the space you're creating for teaching and learning, the six‐word story is a great place to start.

The first time I experienced six‐word stories was with fifth grade students during a memoir‐writing unit. I had been gifted a small book of six‐word memoirs, which inspired an internal excavation of other six‐word story websites and generators. I shared several six‐word stories with the fifth graders, and then challenged the students to write a story about themselves using only six words. At first, they were delighted, especially the students who typically groaned after writing their third sentence. However, soon after the activity started, they grew pleasantly weary … encompassing yourself in so few words is hard!

That's the beauty of the six‐word story. Rather than bucketing energy in grammar, long sentences, and expressive language, the locus of energy is instead put on finding just a few words to describe an experience, event, or even oneself.

I smiled at that memory when I experienced six‐word stories in the Breaths Together for Change adult learning space. At the end of every single session, after we spent almost the entire time talking story, we were asked to document our learning experiences from the session through a photo, captioned with a six‐word story in an online archive.

Throughout the year, we met each month. During our last meeting, we had the opportunity to view the trajectory of our growth, as well as others in the group, by reading through a year's worth of six‐word stories matched with photos in the online archive we created. Some people captioned their photos to further illuminate the connectivity in their stories to their experience.

Typically, when learning is deep and emotional, human capacity for downloading new information decreases. Capturing the essence of learning in fewer words matched with visuals is a more practical and precise way to synthesize individual and group experiences as opposed to reading lengthy testimonials. It is also more practical from a time constraint and/or scheduling point of view.

To use the six‐word story as a storytelling device that promotes learning and growth individually and collectively, consider the following moments and goals to implement this practice:

- Opening up a meeting with students or other colleagues: Use a six‐word story to describe your morning/how you are feeling today/what you are looking forward to today/what's not going well today.

- Assessing a learning experience: Use a six‐word story to describe your learning today. Optional: use a photo that connects to or represents your six‐word story. For groups meeting consistently over time, consider including a six‐word story with a photo after each meeting. Some people may wish to expand their story, captioning their photo with a descriptive connection.

- Envisioning a more just and joyous space: Use a six‐word story to describe what a more just and joyful space would be like for you. Optional: include an image that represents your story. Also, consider weaving the six‐word stories together to create an amalgamation of stories that reflect a collective vision. Post this work somewhere public and visible to hold one another accountable for maintaining and building that shared vision throughout time.

Below, see six‐word story examples from educators in Kapolei, Hawai'i, that exemplify a year's worth of their learning in literacy professional development with my organization, The Minor Collective. This group was accustomed to talking story, and my partner, Cornelius, and I actually learned how to refine this teaching and learning craft from the participants in this group.

On our last meeting date of the year, we (Cornelius and I) first invited them to talk story in small groups. We used the prompts in Figure 4.2 to catalyze their story telling.

After the group of educators engaged in talking story in small groups using the prompts from Figure 4.2, we then invited them to document their stories using the six‐word story device with a representative photo and connective descriptions (option 2 from the earlier goals). In addition to the photo, we also asked them to write a small connective paragraph between their photo and their story to further expand on their thinking. We gave them approximately 15 minutes to work independently. Following are some of their six‐word stories. Find a template to create six‐word stories with your community at https://www.kassandcorn.com/teachingfiercely/.

FIGURE 4.2 Tell the story.

This relates to the conversation I had in breakout groups. Working with incoming Freshmen this year, students have missed out on that growth period within the middle school environment due to being out of school for nearly two years. So students have had to go from an elementary mindset to a high school mindset so quickly. My six‐word story relates to us teachers and students keeping up the fight. To keep going and persevere in such crazy times.

—Teacher, Sophia Carba, Hawai'i

Earlier this year, an elementary librarian sent me a book that she felt was inappropriate for an elementary library. The book Heartstopper Volume 2 is a YA graphic novel featuring queer characters that is being turned into a Netflix series. All 35 of my students in my Gender Sexuality Alliance Club borrowed and read that 1 book in only 2 weeks.

They all shared that our library doesn't have any books about LGBTQ+ folks, and they can't even check out books. Our community library isn't supportive of students spending time there either. Seeing how much the students loved the book, I wrote a DonorsChoose grant to get the full series, books 1–4 and they arrived yesterday. The kids were instantly in love and instead of a GSA meeting, they just wanted to read and share the books together.

I'm not an ELA teacher anymore, so to have kids all over my room sharing books, like they might have in pre‐COVID times, felt special. For an inclusive future that's better for everyone, kids need to see themselves in literacy. When they can't see themselves in books, it's our job as teachers to help them find access to diverse reading material.

I'm also acknowledging that these books are NOT welcome everywhere in our nation, so it's critical that kids know an inclusive future is possible. I've been scared for the mental health of my LGBTQ+ students, and I need them to know a better world is coming, because teachers like us will help build it.

—Sarah “Mili” Milianta‐Laffin, Teacher, Ilima Middle School, Kapolei, Hawai'i

Cocreating a Shared Vision

Sometimes when we collaborate, we are only working with one other person. They might be a “teacher bestie.” Or maybe they are the person you've been matched up with by your school administration, and you are teaching in the same classroom with the same group of kids every day. No matter if you are best friends or complete strangers, these shared reflective practices are important. The students you teach will be able to read your connection or lack thereof. Whether or not you are on the same page is very clear to the children you teach, and when there is dissonance between the grown‐ups they rely on for safety and community, they will absorb that dissonance, resulting in confusion, chaos, or worse.

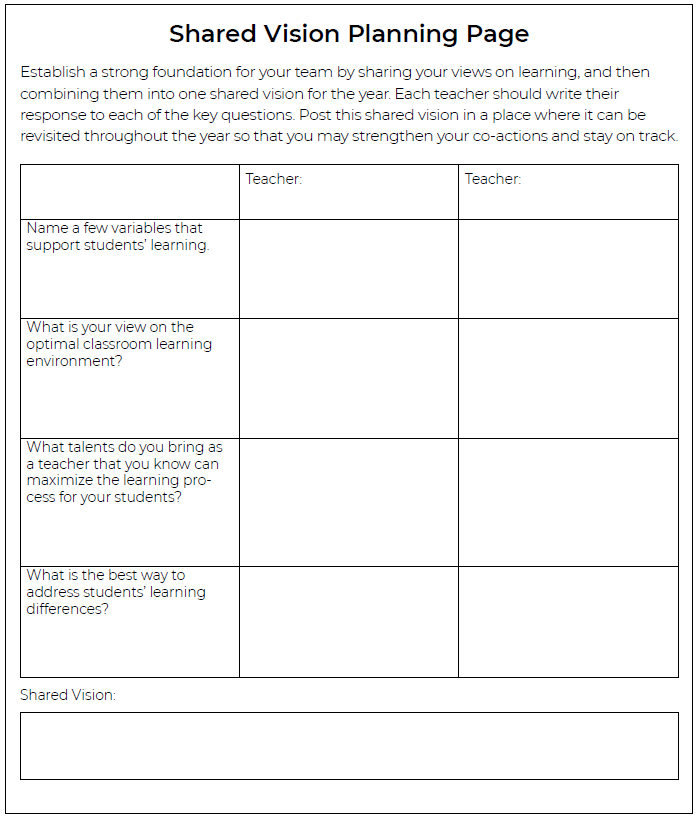

The Shared Vision exercise shown in Figure 4.3 is one way to initiate powerful collaboration, surfacing not just fundamental teaching philosophy beliefs, but also, what you imagine and hope to practice in your instruction, and in developing your classroom community.

FIGURE 4.3 Shared Vision planning template, adapted from Elevating Co‐teaching Through UDL, Elizabeth Stein.

Whether or not you are self‐initiating this collaborative reflection for your own teaching or facilitating it with others, it's a powerful exercise to frame an integrated source of strength that can evolve throughout the year, serving as a point of reference for who you are, what you believe in, and what you are working towards.

In Figures 4.4 and 4.5, see examples of similar work that was facilitated during a co‐teaching institute by myself and my former colleague, Dr. Katie Ledwell, with the Teachers College Inclusive Classrooms Project.

FIGURE 4.4 Chart displaying teacher's shared co‐constructed vision on their shared classroom community.

FIGURE 4.5 Chart displaying teacher's shared co‐constructed vision on their shared classroom community.

- Determine a weekly time you will meet. This is really important. At the beginning of the school year, a lot of excitement is generated with fresh starts and new people, but as the year moves on, people tend to disconnect and meet less frequently. Choosing a weekly time that you and your partner/s will commit to is integral for a routine to become ritualized, that is, marks of your collaboration that you and your partner/s begin to embody.

- Mark the times on your calendars during the meeting. I personally love a shared Google calendar because it allows all people involved to see the event, share attachments and links easily, and also notify meeting participants of any changes in meeting time, place, or structure.

- Hot tip: Google has an excellent “Workspace Learning Center!” Whenever I can't figure out how to do something on Google, I go to support.google.com, and explore the very user‐friendly interface. In Google calendaring, they have helpful tutorials like “What can you do with Calendar?” and “Share your calendar with someone.”

- Other popular web calendars like Apple's Ical are also great, but they tend to be less accessible, especially for those who aren't using an Apple device. Google calendar is available and free on all devices.

- Establish a planning routine. When I wasn't able to stay at school past 3:30 p.m. due to grad school classes in the evening or having to pick up my kids from daycare by 4:00 p.m., my planning routines with my colleagues got really real. If I didn't use my time wisely during the school day, it meant I would be staying up after hours, way past my bedtime, to finish planning and/or preparing for the next day. After one too many late nights, I began to get a lot more intentional about how I spent my teacher prep periods.

- These habits have been long‐lasting, even as my discretionary time evolves.

- At the beginning of each meeting with my collaboration partners, I began to ask what we wanted to accomplish during our time together. After we named those components, we then prioritized what was most important to work on together, and what could be done individually if we ran out of time.

- After that, we did the important work of discussing parts of our shared vision; we weren't just pontificating about our hopes and dreams or hashing out our frustrations because we could talk a good game, or because venting felt pleasant.

- Rather, our conversations were rooted in the daily lived experience of classroom life, including noticings and wonderings we had based on kids' contributions within class, or their worrisome silence. We'd surface current events in light of the curricular themes we had planned on building, and change course if we needed to. We'd take stock of various strategies we were trying, and determine what was working and what wasn't by looking at artifacts and evidence like student work, or family and caregiver's feedback.

- In Figure 4.6, find an example of a co‐planning routine I developed that helped me and my teaching partners organize our thinking, prioritize tasks, and build ideas intentionally while considering the needs of our classroom community. I created this routine when I was working in several co‐teaching relationships, that is, every day I taught with these teachers at the same time in the same classroom.

Embracing Teacher Intellect: Changing the Narrative About Teachers

Next, and perhaps the part of teachers' curriculum‐making journey that is most widely understood as “important work,” is the study and practice piece of how to teach re: how learning works between teachers and students. This is where teachers learn how to teach students foundational skills and strategies like reading, critical thinking, and numeracy. This is also where they learn to develop content knowledge on things like scientific processes and parts of history that are underscored in state curricular standards.

Throughout a teacher's career, they will be tasked with threading those knowledges together in conjunction with the students they teach and the standards and curricula their state/district/school uses. To facilitate this work through the lens of justice and joy, the goal must be to weave a curricular experience that serves their community of young humans in their classrooms from year to year along a continuum of change.

FIGURE 4.6 Co‐planning routine for teacher partnerships.

However, student‐centered curriculum is somewhat of a rarity in schools for a variety of reasons.

It's not easy, this complex fabric of curricular experiences teachers are tasked with weaving. Too often, the young humans are left out of the fabric construction when curricula is packaged and mandated to be delivered in very specific ways. Additionally, those aforementioned important knowledges essential to the foundations of learning are skirted over in university‐based teacher preparation programs, and/or are scarcely revisited during the time in which teachers are connected to young people in schools. Think about the scant teacher preparation I described in the beginning of this section—after a mere six weeks I was granted full jurisdiction of teaching several groups of students by myself.

The Educational Industrial Complex also poses a threat to the ways in which teachers are positioned to creatively adapt the curriculum they are given to implement. State legislation, local policies, and the oversight of classroom‐based decision‐making from various school boards and other parent /caregiver groups challenges teachers' work even further.

I put important work in quotation marks earlier because prescribed and packaged curriculum is an affront to holding teacher knowledge valuable or something worth investing in. When we strip vital decision‐making processes away from the people who spend the most time with and are in closest proximity to young learners in school, it is an injustice to both teachers' and students' humanity.

(I want to reiterate here: this is not teachers' fault. This is another example of how deeply rooted and multifaceted injustices have spread throughout our schools.)

The general disregard of teacher intellect in the United States has been generated by public rhetoric, multiple news outlets, and social media. For example, Time magazine featured a series on teachers in America in September 2018. It showed multiple magazine covers with exhausted looking teachers sitting in empty classrooms, forlorn expressions on their faces, looking into the distance. One photo's tagline read: “I have a master's degree, 16 years of experience, work two extra jobs, and donate plasma to pay the bills. I'm a teacher in America” (Reilly 2018). Also published in Fall 2018 was a New York Times Magazine issue featuring multiple articles on teaching and education, with its cover plastered in bold, protest‐style font: “TEACHERS JUST WANT TO TEACH, BUT THE CLASSROOM HAS BECOME A BATTLEGROUND.”

While it is absolutely true that teachers are underpaid, overworked, and, most of all, underappreciated, this narrative constructed by American media and the general public paints a bleak, underwritten, depressing, and incomplete picture of what being a teacher is like and who teachers are.

This is where multiple truths are important to hold.

It is also true that schools, government, and families have dangerous tensions brewing over myriad issues regarding what's best for kids, what's best for teachers, and what is and what is not in the realm of administrative responsibilities.

What's more is that the teacher shortage, a long‐time issue in rural and urban centers, has been exacerbated by the COVID‐19 global pandemic and within the coming years is projected to grow even larger. In Fall 2022, there were reportedly 570,000 fewer educators working in public schools, with roughly 40,000 teaching vacancies (Lowrey 2022). Current trends show that by 2025, schools in the United States will be understaffed—with up to 200,000 teacher positions unfulfilled (Jacques 2022).

And … there is so much more to the story of teachers, what it means to teach, to learn, to the full, whole, beautiful, brilliant people, who, for most of us with children, thank our blessings they are in their care for six hours every day.

Where is the part that tells the story about teachers who are present, or those who are serving the children in their communities outside of the classroom or beyond? How despite all the challenges teachers are faced with, and the minimal love American culture pushes their way, more than 3 million teachers across the United States (National Center for Educational Statistics Data n.d.) still remain committed to the work. And some of those who have left their school communities remain committed to kids' learning in different ways.

“Committed to the work” is a phrase I would use to describe many teachers I know, and many of whom I don't know personally, but have read or heard about and appreciate from afar. While teaching in primary and secondary schools, there were times I used to feel unstoppable in the classroom, like “The Force”4 lived within me. There was nothing a student brought to me that I didn't try to figure out. I learned each one of them. I integrated a group of fourth and fifth graders with the thickest IEPs in the whole school into the greater school community; they participated on field trips, they created spoken word performances, they created beautiful works of art, they studied the world that surrounded them. They left our classroom space with stronger literacy and numeracy skills, they developed more powerful emotional literacy, they were proud of themselves, and their peers and parents were in awe of them. And I know I didn't do this alone. I had a whole team of people working in community for the young humans who attended our school to get the kind of education they deserved.

But I left the classroom space because I felt like it started to restrict my growth. The hierarchies embedded with in the school system—such as the idea that teachers should ask permission to try something differently, or professional learning should be facilitated so specifically—to me felt suffocating. There were times I felt like my creativity was getting me in “trouble.” I felt like the teacher agency developed from the learning communities I was a part of wasn't always appreciated and, perhaps worse, may have even felt threatening to some people in my community.

Whether or not that weight I felt was real or in my head, nonetheless, it pushed me out of classroom teaching and into a different role, that of coach and documentarian for TCICP at the time. Even though my creativity felt subdued, my ambition and commitment to building the bedrock of just schooling and joyful curiosity remained. Leaving the classroom wasn't an easy decision. Six years out, it is the one space I continue to long for no matter where my educational journey takes me. It is also the space that informs my current work along my educational journey.

My role now is to support teachers like my former self in the classroom, and also those educators who are far away from feeling any sort of agency. It's important to not feel as though leaving the classroom into a coaching role is “moving up.” I want to flatten hierarchies that school communities uphold, and I want to create lateral circles of leadership for teachers and students and families to participate in and be proud of.

In my post‐classroom teaching days, I often ask myself as a coach: Who did I need, what did I need, and what did my coworkers and students need? What knowledge and experiences were we missing? The thought sanctuary I described in Chapter 3 is paramount. Countless experiences as teacher and as coach have continuously shown the need for teachers to sit alone, sit together, and be provided with ample time for soaking in the days’ experiences in order to plan for tomorrow's learning.

Historical Underpinings: Gauging “Smart”

As we consider the injustice and justices regarding the narrative on teachers, here, we pause to venture back in time to see the linkage between how we value our own intelligence, as well as our students', and standardized testing: https://www.kassandcorn.com/teachingfiercely/.

Notes

- 1 In New York State, Integrated Co‐Teaching, widely known as ICT, is a component of the spectrum of special education services wherein two teachers—one general educator and one special educator—teach in a class to provide accommodations and specially designed instruction within a general education classroom. Up to 12 students, or 40% of students in the classroom community, may have IEPs.

- 2 Acronym for Universal Design for Learning.

- 3 Given what I now know about Dr. Suess's racist and harmful imagery displayed in texts he authored and illustrated such as If I Ran a Zoo, where Black characters are portrayed as monkeys as Asian characters march with armed white men behind them (just one example of several of his publications that dehumanize Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color (Gatluak 2021), I would definitely choose a different text to match with a film about climate change. In the later years of my teacherhood, I built curricular units on climate change with young people, and we chose to use Spike Lee's documentary on Hurricane Katrina, When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts.

- 4 Yes, “The Force“ as described in Star Wars! The one that runs through you and gives you energy to move boldly with your instinct, your mind, and your heart!