Set Up Basic Security

Time to start improving your security! This chapter contains steps so fundamental to your security that you’d be doing yourself a huge disservice to avoid them. Just as you need to check that the appliance is plugged in before you call customer service, the steps in this chapter constitute a sort of minimum threshold for security awareness.

This chapters covers keeping macOS and third-party software up to date, configuring security and privacy settings in macOS (particularly regarding locking your Mac when you’re not in front of it),

Keep Your Software Up to Date

It’s a fact of life: software has bugs. And some of those bugs result in security vulnerabilities. Fortunately, most major software vendors, including Apple, have teams of programmers working constantly to identify and fix security-related bugs.

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve read breathless news reports about some newly discovered and seemingly disastrous Mac security issue, only to see a software update from Apple fix it a few days later before any damage occurs. This is Apple’s normal pattern, and it’s why you should never lose sleep about the Mac security crisis du jour.

However, Apple security updates don’t help unless you install them! If you have automatic software updates turned off and never bother to check for updates, you could be needlessly putting your Mac and your data at risk from problems that were solved months or years ago.

Software updates fall into several categories, all of which can fix security issues:

Major upgrades to macOS, such as from Monterey to Ventura

Minor updates to macOS, which can be small increments for big fixes (13.1.0 to 13.1.1), or larger ones when they include feature changes but not a full OS upgrade (such as 13.0.1 to 13.1)

Standalone security updates for macOS that fix specific pieces of system software, usually stuff deep beneath the surface

Updates to individual Apple apps (Safari, Music, Books, QuickTime Player, etc.)

Updates to third-party apps

Which of these should you keep up with? Ideally, all of them, but at a bare minimum, install the standalone security updates. After ensuring you haven’t heard of any problems other people have had, install minor updates. Major macOS updates require more planning and include quite a lot beyond security fixes.

In most cases, Apple releases security updates, for the current version of macOS and the previous two. An update in mid-2023 would include Ventura, Monterey, and Big Sur. If you aren’t at least on the third-most-recent version of macOS, you risk being vulnerable to known security problems that Apple won’t ever fix.

Meanwhile, each major new version of macOS contains entirely new security features, independent of bug fixes. Ventura offers certain intrinsic protections that Monterey did not, and Monterey had security features that Big Sur lacked. So if you really want all the latest security goodness, you should—if your hardware supports it—upgrade to the latest version of macOS and install all the pertinent macOS, security, and app updates.

Apple delivers minor and major macOS updates and security updates through Software Update:

Monterey or earlier: Go to System Preferences > Software Update.

Ventura or later: Go to System Settings > General > Software Update.

When I reference Software Update below and in later sections, use that navigation to navigate to the correct location.

App updates happen via App Store app. You can configure how updates are installed in both places, as I describe next.

Configure System Updates

Apple used to take the peculiar path of using the App Store to deliver system updates. For several releases, these have had their own, more sensible preference pane—which also, oddly enough, also has one preference related to the App Store.

To reduce complexity and confusion, Software Update is extremely stripped down, particularly compared to past versions. It also looks roughly the same from Catalina to Monterey. Even in Ventura, it’s only redesigned, not reinvented.

Software Update shows whether you’re up to date, and it notes if there are software updates available if you are not. If you’re a major system update behind (or further), it also shows an area at the top urging that installation a secondary area below, the pane may read “Another update is available” for Safari and security updates, and you have to click “More info” to discover which are and proceed to install them.

You can completely automate minor macOS, security, and other updates—in fact, that’s the default. (Major macOS updates require direct action.) However, in Monterey and earlier, you can click the Advanced button to see settings and make changes (Figure 1). In Ventura or later, click the info ![]() icon (Figure 2).

icon (Figure 2).

Here’s what macOS does without intervention:

Check for updates: Whenever you open Software Update, it checks for new updates; it also checks in the background, and puts a red badge on System Preferences or System Settings indicating how many there are.

Download new updates when available: This includes all the updates listed below. The advantage is that they are either installed automatically, or available for immediate installation if you install manually. Disable this if you’re bandwidth limited or pay for bandwidth, and want to plan downloads.

Install macOS updates: This includes all “dot” updates, like moving from 13.0.0 to 13.0.1 and from 13.0.1 to 13.1.0.

Install app updates from the App Store: Any app you purchased or acquired by the App Store is automatically updated. If disabled, launch the App Store as described below.

Install system data files and security updates (Monterey and earlier): Apple has both standalone security updates, mentioned above, and certain data files that are used to block newly discovered malicious apps and for related security purposes. There’s really no reason to uncheck this.

Install Security Responses and System files (Ventura): Apple has added Rapid Security Response updates in Ventura—exploit fixes that can be installed automatically and don’t require a reboot—and relabeled this entry to be more inclusive of them.

In most cases, you can view a list of available updates, deselect or select items in the list, select items to view their contents, and click Install Now to proceed towards installation. Updates that require restarting your Mac are noted with “Restart Required” after their title in the detail section, and you’re warned when you click Install Now that you will need to let the updater restart your Mac to complete it.

Configure App Store Updates

The App Store is where you buy apps and acquire free apps, including those with in-app purchases, that have gone through additional layers of vetting from Apple. Among certain advantages are that you don’t need to use the app or go to a website to find out if the latest version is installed.

The App Store has an Updates link in its navigation bar at left. Click that and you can see available updates and recently installed ones. You can also use App Store’s Preferences to control automatic updates (Figure 3): select or deselect Automatic Updates, and that modifies the same setting as in System Preferences > Software Update > Advanced (Monterey and earlier) or System Settings > General > Software Update > info ![]() icon (Ventura).

icon (Ventura).

Update Other Apps

Software that didn’t come from the App Store must be updated separately. Fortunately, most apps include an automatic, configurable update check whenever you launch them, and also check for updates periodically. You can disable this in nearly all apps, though I recommend keeping the feature on, or enabling it if it’s turned off by default.

If you haven’t seen update notifications lately, or aren’t sure how your favorite apps have automatic updates configured, now is the time to check. Launch each app, select its option to check, and install updates.

I have found that some apps say they will post an alert about an update whenever one appears, and then do not. The Zoom app for macOS was particularly bad for over a year until the developers finally started to alert users properly to new versions.

Manage Basic Security and Privacy Settings

The Security & Privacy pane of System Preferences (Monterey and earlier) in Figure 4 or System Settings > Privacy & Security (Ventura) collects many kinds of controls and options. While I will cover some of them in other parts of the book, I want to draw your attention for now to a few especially important settings.

I’ll also mention settings in Users & Groups, Touch ID & Password (Ventura), and Lock Screen (Ventura), and in the Keychain Access utility, that deserve a quick look.

General Security Preferences

The General tab in Monterey and earlier offers two distinct sections that are effectively unrelated. At the top, you can set a number of password preferences. In Ventura, these preferences have been relocated into Settings > Touch ID & Password and Lock Screen.

Adjust Password Preferences

The top option in General (Monterey and earlier) and Touch ID & Password (Ventura) says “A login password has been set for this user” if one has been set. Click Change Password or Change to update it.

In the same area in Monterey or earlier or in Settings > Lock Screen in Ventura, check “Require password” to force your Mac to lock when it goes to sleep, or when the screen saver activates and a period of time passes. Select “immediately” and the Mac is locked the instant it goes to sleep or starts showing flying toasters. You can also set it to wait for durations from 5 seconds to 8 hours.

When you return, you can enter the password; on Macs with built-in or keyboard-based Touch ID enabled, unlock with, uh, Touch ID. See Enable Touch ID later in this chapter for more information.

Nearly everyone should enable “Require password” for the same reason noted above: unless you shut your Mac down every time you walk away from it, anyone with physical access can jiggle the mouse or touch the trackpad and access your stuff.

You can crank that up a notch if you’re at a higher risk of physical access or theft: click the Advanced button and select “Log out after…” (Monterey or earlier) or “Log out automatically after inactivity” (Ventura) and choose a duration in minutes. The Mac logs itself out of your account after that period passes, raising the bar for a physical break-in. While the lock screen should be sufficient, background apps and other settings are in effect that could make your machine slightly more at risk than if it’s in a logged-out state.

If you have an Apple Watch, an iPhone running iOS 10.13 or later, and a mid-2013 or later Mac model, and they’re all signed into the same iCloud account, you will have an additional option in System Settings > Touch ID & Password: “Use your Apple Watch to unlock apps and your Mac.” Select this if you want your Mac, when locked, to be automatically unlocked whenever you’re close by and wearing your Watch. If you own multiple Watches, you can select which one.

Just tap the keyboard, keypad, or mouse, as if you were jostling it to get it to show you a password dialog or a Touch ID prompt, and the Watch and Mac have a conversation. Bluetooth and Wi-Fi must be enabled on the Mac for it to work.

Optionally, you can have a message appear on a lock screen:

Monterey and earlier: In System Preferences > Security & Privacy > General, unlock the pane, click “Show a message when the screen is locked,” click Set Lock Message, and enter the message.

Ventura: In Settings > Lock Screen, enable “Show message when locked,” click the Set button, enter a message, and click OK.

This message can be useful if other people use the same Mac and you want to alert them as to why it’s idle.

Control Which Apps Launch

Apple hides its powerful Gatekeeper technology behind a radio button selection. Gatekeeper prevents malicious software from easily taking root on a Mac, even on a naïve user’s computer (not you, to be sure). You can find the setting “Allows apps downloaded from” in System Preferences > Security & Privacy > General (Monterey or earlier) or System Settings > Privacy & Security (Ventura).

You have two options:

App Store

App Store and identified developers

I recommend the second option, unless you’re setting up a computer for someone who needs more handholding and protection. For a full explanation of how Gatekeeper works, see a couple chapters ahead in Apple Protects with Gatekeeper.

You can select a different option whenever you like, but it only affects apps launching after that point. Switch from “App Store and identified developers” to App Store, and you can still launch any third-party apps you had previously run, but macOS prevents new non-App Store apps from being validated.

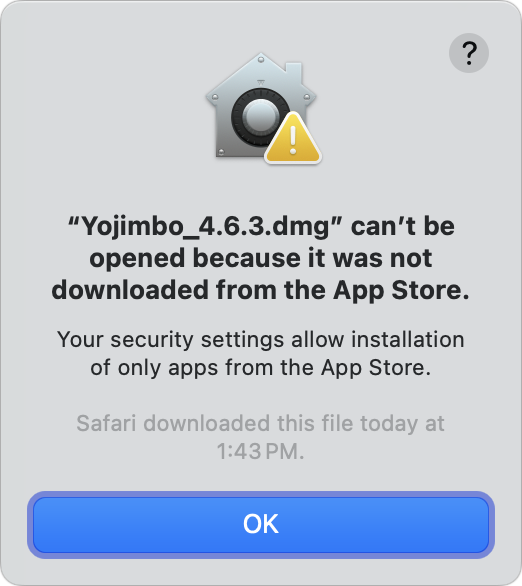

Apple added a helpful prompt in Big Sur: if you have the launch option set to App Store and attempt to open a third-party app, macOS first tells you why it can’t launch (Figure 5).

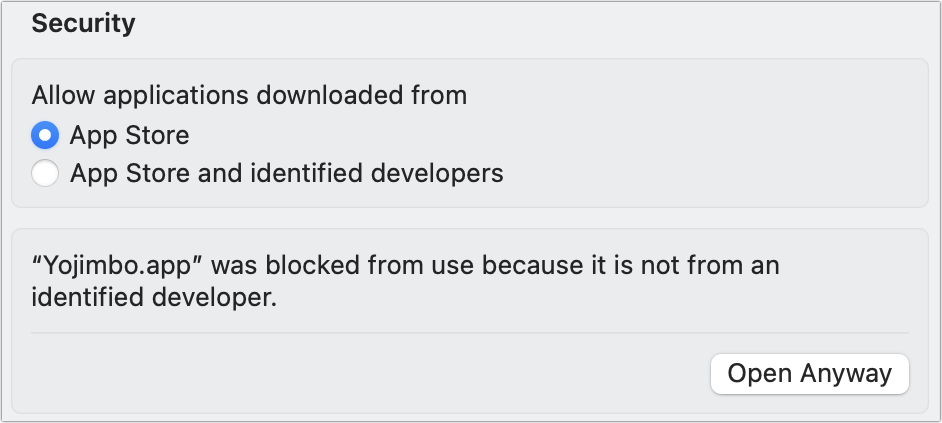

However, if you then return to the “Allow apps downloaded from” location in your version of macOS, you see a helpful Open Anyway button (Figure 6). That’s a little informal, but makes sense: you made this choice, so why not?

Manage System Extensions

If you’re a long-time Mac user like me, you remember “system extensions” from System 7 or Mac OS 9 or the like: these were files you put into a special folder that would get invoked at launch to modify basic system behavior, sometimes at a very low level.

Well, we may be 20 to 35 years past that earlier generation of Mac software, but they’re back, baby! For most of the lifetime of OS X and macOS, Apple let developers add low-level functions through kernel extensions, which have a lot of privileges and can cause huge problems if handled wrong. But some software, particularly anti-malware apps and drivers for input devices like Wacom graphics tablets, had no choice but to patch in at that low level.

In their ongoing battle of limiting user exposure to malicious or disruptive anything, Apple told developers in 2019 they would eventually not allow kernel extensions, replacing them with system extensions, which run with substantially fewer privileges, but actually give developers a lot more carefully controlled capabilities.

Apple mediates access to “legacy” kernel extensions and new system extensions through the General tab in Security & Privacy (Monterey and earlier) or System Settings > Privacy & Security in Ventura.

For instance, I have a Wacom tablet, and the way it used to capture input required a kernel-level shunt to route data to its drivers. When I installed the software back in Mojave, a message appeared in the Finder that explained “System Extension Blocked” with an OK button. macOS told me to go to System Preferences > Security & Privacy (while running Monterey).

On the General tab a note appeared that said, “System software from developer ‘Wacom’ was blocked from loading.” An Allow button let me install it. (This message disappears after 30 minutes if you take no action, and you have to run the installer again.) Some extensions require a restart and you’re given a button for that as in Figure 6.

However, once approved, if the extensions have trouble loading or need new permission—which can happen if you upgrade macOS—a Details button appears near the message (Figure 7). Click it and you can find extensions available to add (Figure 8).

Some extensions require a restart. If you select any box and click OK and a restart is required, macOS won’t let you exit System Preferences (Monterey and earlier) or System Settings (Ventura) without initiating a restart.

Automatic Login Option

When you set up a new Mac, one of the first things you are prompted to do is create a user account for yourself by picking a username and a password. (Your Mac can have many such accounts, but it must have at least one.) By default, macOS logs in that initial user account automatically when you turn on or restart your Mac. That means you can get right to work without entering a password, and it’s the most convenient arrangement for Macs with a single user—especially if the Mac is kept in a secure place.

However, if anyone else (including a thief!) can get to your Mac, that automatic login becomes a problem, because your Keychain unlocks automatically (see Keychain Security, next) and all the files on your Mac are readily available.

If there’s a risk of someone gaining access to your Mac, you should disable this option by selecting Off. It’s found in Monterey and earlier in System Preferences > Users & Groups > Login Options as the “Automatic login” menu, or in Ventura at System Settings > Users & Groups as a popup menu next to “Automatically log in as.”

Launch Items

Many apps have startup activities you can manage. This includes launching an app when you log in and components of apps launching to run in the background continuously. From a security perspective, you should know what’s launching and occasionally check to see whether anything new has appeared that you’re unaware of.

Login Items

Apps can add themselves to a list of items that open when you log in to your account. You can also add items manually. This Login Items list is unique to the current user logged in.

In Monterey and earlier, Apple located it with user settings in System Preferences > Users & Groups > Your User Entry > Login Items (Figure 9). In Ventura, it’s a bit more logically located in System Settings > General > Login Items (Figure 10).

Starting in Ventura, Apple steps up on the disclosure and security front. macOS alerts you when an app adds itself or a component to the Login Items list (Figure 11).

You can take several actions on the items in this list:

Hide (Monterey and earlier): Check the app’s box in the Hide column so its windows hide themselves after launch.

Remove: Select one or more apps and click the minus

icon to remove them. There’s no prompt—it just happens.

icon to remove them. There’s no prompt—it just happens.Add: Click the plus

icon and then select one or more apps, documents, or network servers to open or mount at launch.

icon and then select one or more apps, documents, or network servers to open or mount at launch.

If you want to prevent all login items from launching, you can do so temporarily in one of two ways:

At a login screen, hold down the Shift key when clicking the login

icon. Keep holding down shift until you see the Dock appear.

icon. Keep holding down shift until you see the Dock appear.Restart your Mac. Hold down the Shift key when the progress bar starts and release after you see the desktop appear.

Allow in the Background

Starting in Ventura, macOS also gives you insight and control over components of apps that are set to run in the background. First, you’re alerted when app installs them (Figure 12).

Then, you can find a list of these items in System Settings > General > Login Items under the Allow in the Background heading (Figure 13).

While you can’t remove them via this interface, you can enable and disable them. When you disable background items, you’re prompted to authenticate with Touch ID or your password.

Items that are installed without the full information required by Apple are shown with an info ![]() icon. Click it, and it opens the component in the system or user Library folder it lives in.

icon. Click it, and it opens the component in the system or user Library folder it lives in.

Keychain Security

Your Mac’s Keychain contains passwords for lots of different things that need to be both available on demand and secured against unwanted access. This includes passwords to log in to apps and Wi-Fi networks, passkeys for websites at which you’ve enrolled to use them, credentials for local network servers, encryption certificates, and other important information your Mac needs to function securely.

If you use iCloud Keychain and use the Safari browser, Keychain also contains credentials for websites where you have accounts, and may have your credit card details, too, separate from stored Apple Pay credit card information on Macs with Touch ID or an M-series Mac paired with a Magic Keyboard with Touch ID.

Because this information is valuable and potentially sensitive, macOS encrypts the contents of your Keychain. However, whenever your Keychain is unlocked, your credentials can be passed to apps, websites, and network services without any intervention on your part.

And how do you unlock your Keychain? That’s the crazy part: all you have to do is log in to your Mac’s user account. And—as we saw in Automatic Login Option—another default setting is to log you in to your account automatically.

In other words, unless you take steps to change the defaults, merely turning on your Mac might unlock your Keychain!

Anyone else who might have physical access to your Mac could then log in to all the web accounts (like your bank, Amazon, or PayPal), file servers, and other resources for which you’ve saved credentials (like Music or the App Store).

There are a few bright spots:

No one can see the actual Keychain entry’s secure text without knowing your macOS account login password.

Within Safari, an unwanted party can’t get a list of all the sites at which you have passwords stored from Safari, Keychain, or System Preferences/System Settings > Passwords (in Monterey or Ventura) without your password.

Even when a password is autofilled in Safari or in an app, there’s typically no way to copy the password to view it as text.

Macs with active Touch ID hardware and password autofill enabled will drop your password in only if you use a valid fingerprint or enter your password (System Preferences > Touch ID > Password AutoFill in Monterey and earlier or System Settings > Touch ID & Password > “Use Touch ID for autofilling passwords” in Ventura).

Yet the storm cloud lingers: someone can use all your passwords when the conditions above aren’t true. These actions will help prevent that:

Turn on FileVault: Because FileVault is a high-value way to prevent power-up access to your computer, many people should turn it on; see FileVault Protection. However, some people may find it more trouble than the potential of losing access to their files in certain cases; see Decide on Using FileVault.

Turn off automatic login, if you don’t have FileVault enabled: I explain just above, in Automatic Login Option, how to disable automatic login.

Enable Touch ID and AutoFill: This blocks access to autofilled passwords without your fingerprint or password.

Lock your Mac after a duration: As noted in Adjust Password Preferences.

Configure Accounts & Groups Securely

While macOS is a friendly operating system, it’s all Unix under the hood, which means it runs by partitioning access to files and apps by users and groups, selectively providing permission based on who you are and what groups you belong to.

Although I cover this topic from another angle later (see Keep Data Safe from Other Local Users), let’s cover several important principles about user accounts:

There are four main types of Mac user accounts: administrator, standard, guest user, and sharing-only. Of these, administrator and standard are by far the most common. The usual reason to have more than one account is so that each person who uses a particular Mac can have a separate space for files and settings. But accounts can also be used to restrict access to certain files or resources in order to improve your security.

Every Mac needs at least one administrator account. When you set up a new Mac or perform a clean installation of macOS, you’ll be prompted to create an administrator account before you can do anything else. That’s because only administrators can perform certain crucial tasks (see the next bullet point). You can have more than one administrator account, and in fact, it isn’t a bad idea to set up an extra one to use for testing and troubleshooting.

Administrator accounts are all-powerful. Administrators can create, modify, and delete other user accounts. They can unlock any pane of System Preferences (Monterey and earlier) or System Settings (Ventura), and authorize any type of software installation. They can (with a quick trip to the Terminal utility) open any file on the Mac, belonging to any user—and can change any file’s permissions; in Catalina or later, they’re restricted to changing user files. They can upgrade macOS to a new version. On an Intel-based Mac, they can set or remove a firmware password that prevents the Mac from booting from anything other than the default startup disk. The list goes on and on.

Standard accounts can do most ordinary things. Standard users can run apps, work with files, and perform most ordinary day-to-day tasks. When a user with a standard account tries to do something that only an administrator is allowed to do, simply entering an administrator’s username and password (or having an administrator do so) does the trick—there’s no need to log out or switch accounts first.

Apps get their privileges from the user who opens them. If someone with a standard account launches an app, that app can access only the files and folders available to that user. If someone with an administrator account launches an app, that app has more expansive access to files on the Mac, although sandboxing limits that scope somewhat; see Deter Invasion via Sandboxing. A malicious or compromised app launched by someone with an administrator account might be able to do serious damage across the Mac.

You can create as many user accounts as you need, and switch between them easily. To keep your Mac secure, you should make sure you have the right number and types of accounts, as I discuss ahead.

Set Up a Standard Account for Others

A standard account has permission mostly to affect files and applications installed within the Home > Username folder. It’s the right kind of account to set up for people using a Mac who aren’t sophisticated users, don’t need system-level access or the ability to install apps for all users, or shouldn’t be given the same level of trust on a shared computer as its owner or administrator.

If your main account is currently an administrator account but you want to make it a standard account, you can create a new administrator account (for occasional use only) and then remove the administrative privileges from your main account. To do so, start with these steps in Monterey or earlier:

Go to System Preferences > Users & Groups.

Unlock the pane with your current administrator password.

Click the plus

icon to add a new account.

icon to add a new account.

Start with these steps in Ventura:

Go to System Settings > Users & Groups.

Click the Add Account button.

Enter your password if prompted.

Now in all versions of macOS:

Choose Administrator from the New Account pop-up menu.

Fill in the fields for Full Name and Account Name (that is, a short username, such as your initials).

Create a strong password and enter it in the Password and Verify fields; optionally enter a password hint.

Click Create User. If you had automatic login enabled, an alert appears, asking if you want to keep it on or turn it off. Click Turn Off Automatic Login. (This won’t appear with FileVault enabled.)

Choose Apple > Log Out Username to log out of your old administrator account.

Select or enter the name of the new administrator account you just created, enter its password, and click the arrow button or press Return.

At this point, you may be prompted to enter the Apple ID for the new account. Since this administrator account will be for occasional use only, I suggest selecting the Don’t Sign In radio button, clicking Continue, and then confirming by clicking Skip again. If it turns out you need iCloud services with your new administrator account, you can always set them up later.

Once again, go to System Preferences > Users & Groups (Monterey and earlier) or System Settings > Users & Groups (Ventura).

Next, either:

In Monterey or earlier, click the lock

icon, and authenticate, this time with your new administrator credentials. In the list on the left, select your old administrator account.

icon, and authenticate, this time with your new administrator credentials. In the list on the left, select your old administrator account.In Ventura, click the info

icon next to the old administrator account, then use the credentials for your new administrator account to authenticate (Figure 15).

icon next to the old administrator account, then use the credentials for your new administrator account to authenticate (Figure 15).

Figure 15: Use the account modification view to remove administrator permissions in Ventura. Deselect or disable “Allow user to administer this computer”; this turns your erstwhile administrator account into a standard account. An alert appears, claiming that you must restart for the changes to take effect. That’s not entirely true (you need only log out), but click OK anyway.

Choose Apple > Log Out username to log out of your new administrator account.

Select or enter the name of your old (previously administrator, now standard) account, enter your password, and click Log In.

Having done all this, you’ll find that almost everything about using your Mac is exactly as it was before. But there’s one exception: when a dialog prompts you for an administrator’s credentials, you won’t enter the username and password for your everyday account but instead enter the credentials for your new administrator account.

Set Up a Guest User Account

As long as you’re making changes in Users & Groups, you should think about whether you want to have a guest user account. It’s enabled by default starting way back in Yosemite. That’s usually a good idea, but if it doesn’t suit your needs, you can disable it.

With a guest user account enabled, you have a spare—and, importantly, non-administrator—account that anyone can log in to without a password. When logged in, they can run apps installed for all users, browse the web, or perform any other task that doesn’t require saving private information to disk permanently. (Guest users can, however, save data to publicly shared locations.)

As soon as the guest logs out, macOS deletes the guest’s temporary home folder, leaving everything just as it was beforehand. If you ever need to give someone temporary access to your computer, using the guest account is simpler than having to set up and later delete a conventional account for that person, and more secure than letting them use your account.

To turn guest access on or off in Monterey or earlier:

Go to System Preferences > Users & Groups.

Enter your administrator password if prompted.

Select Guest User in the list on the left. Then select or deselect “Allow guests to log in to this computer.”

To turn guest access on or off in Ventura:

Go to System Settings > Users & Groups.

Click the info

icon to the right of the Guest User entry.

icon to the right of the Guest User entry.Enter your administrator password if prompted.

Enable or disable “Allow guests to log in to this computer.”

With guest access enabled in any version of macOS, you can optionally select either or both of the following checkboxes in the Guest User settings:

Limit Adult Websites: Apple used to offer more expansive limitations, but now just blacklists risqué-and-beyond sites.

Allow guest users to connect to shared folders: This doesn’t affect the way someone logged in as a guest can access shared folders on this Mac, as you might expect. Rather, when selected, people on other devices on the network can connect to this Mac’s shared folders without supplying a username and password.

Make Sure Regular Users Have Accounts

If you’re the only person who uses your Mac, you can skip this topic. But if you share your Mac with family members, coworkers, or friends, do yourself—and them—a favor and create a separate (standard) account for each person. And then, insist that everyone log in to their user-specific accounts when using the Mac. That way, any damage (accidentally deleted files, changed preferences, and so on) will be restricted to that user’s space and not affect the entire Mac.

To enable switching from one user to another without having to log out (and thus quit all your apps):

In Monterey or earlier: Go to System Preferences > Users & Groups > Login Options and select “Show fast user switching menu As,” choosing from the pop-up menu Full Name, Account Name, or Icon. A menu appears on the system menu bar.

In Ventura: Go to System Settings > Users & Groups > Control Center. In the Fast User Switching section, choose Don’t Show, Full Name, Account Name or Icon from the Show in Menu Bar pop-up menu. You can also opt to have an icon appear in Control Center by enabling that option.

To switch users, choose the name of the user you want to log in as from that menu, which appears near the right side of your menu bar, and enter that user’s password. With the Control Center option turned on in Ventura, you can click the account ![]() icon to reveal the same menu.

icon to reveal the same menu.

That menu (and Control Center item) also lets you drop into the Login Window screen by selecting that item.

Control Adding USB and Thunderbolt Devices

Apple extended a feature in macOS 13 Ventura that they brought earlier to iOS/iPadOS that blocks connecting peripherals without explicit access. On a Mac, that includes USB and Thunderbolt devices.

The feature is a line item in System Settings > Privacy & Security labeled “Allow accessories to connect.”

You have four options:

Ask every time

Ask for new accessories

Automatically when unlocked

Always

In any case in which you have to grant permission, you must enter your administrator permission—Touch ID, even when available, isn’t considered a high-enough bar.

Enable Touch ID

Touch ID is a terrific safeguard to layer on top of other basic protections. By letting you use a fingerprint to unlock your Mac, it increases security on your Mac while also making it easier for you (or someone else with an authorized fingerprint) to log in.

Touch ID is such a great idea that Apple extended its availability from iPhones and then iPads to Macs starting with the 2016 Touch Bar model of the MacBook Pro. It was later added to all new MacBook Pro models and the MacBook Air starting in 2018, including those that use an M-series processor.

In May 2021, Apple released the Magic Keyboard with Touch ID (in both standard and extended versions) along with their new M1 iMac. This brought Touch ID to a desktop Mac for the first time. Apple later began selling this version of the Magic Keyboard separately, and while the keyboard part works with any Mac, the Touch ID sensor requires an M-series processor.

You can enroll your Mac to use Touch ID via System Preferences > Touch ID (Monterey and earlier) or System Settings > Touch ID & Password (Ventura):

Click Add Fingerprint.

Follow the prompts to fill in the fingerprint’s main portion, and then the edges.

Click Done.

Name the fingerprint descriptively (Figure 16).

I like to enroll several of my fingertips, because it’s a one-time process and it lets me not have to remember which finger is the right one. You can have a total of three. This can include someone else in your household or you know if you want them to have the ability to unlock your Mac or other features.

Apple lets you choose to enable Touch ID to unlock your Mac, use Apple Pay, pay for items in Apple’s various stores, validate that you want to automatically fill in a password field in Safari and some other locations, and switch between user accounts when fast user switching is turned on.

Some third-party Mac apps offer Touch ID as a verification option, just as many do in iOS and iPadOS.