4 Individual and Team Diagnostic

No one collaborates alone.

Self-evident? Maybe so. But let’s dig a little deeper into the implications of this seemingly simple statement.

If today’s most important business problems are indeed highly complex, then strong teams have to be brought together to work collaboratively on tackling them.

But how do these strong teams really operate? To answer this question, we need insights on two levels: the team and the individual. First, the team leader has to understand the talent on that team. We generally steer away from sports metaphors, but in this case it’s pretty hard to avoid one. Who wins the World Cup, the America’s Cup, the World Series, or the Tour de France? The answer: the team that most effectively combines a group of star contributors with different and complementary skills, and knows how to use each person’s strengths as part of that team.

Self-awareness is the starting point for individual insights. Team members, and their managers, need to understand how they tend to act at work. For example, is it more natural for them to take control of a project, or to delegate readily and easily? Are they better at launching a new initiative, or at refining one that’s already in progress? Some of those insights arise merely through reflection, but people tend to miss some critical “ah-ha” moments unless guided in their reflection.

And then comes the second tough challenge. Someone has to manage those stars, making sure that the team dynamics are pointing the team toward victory. Generally speaking, this means getting people to play to their strengths and to focus consciously on using those strengths to improve collaboration and capitalize on its advantages.

In the following pages, we explore how both individual attributes and team dynamics contribute to understanding and using collaborative strengths. We’ll begin with individual attributes, emphasizing a tool that can help people understand their own particular strengths.

On the Individual Level: The Seven Behavioral Dimensions of Smart Collaboration

Human motivation is complicated, and it’s sometimes tempting to interpret collaborative behavior as an undifferentiated blob of be-nice impulses. But our decade of research (see sidebar) shows otherwise. We can identify which behaviors really matter, and how to use them to foster collaboration.

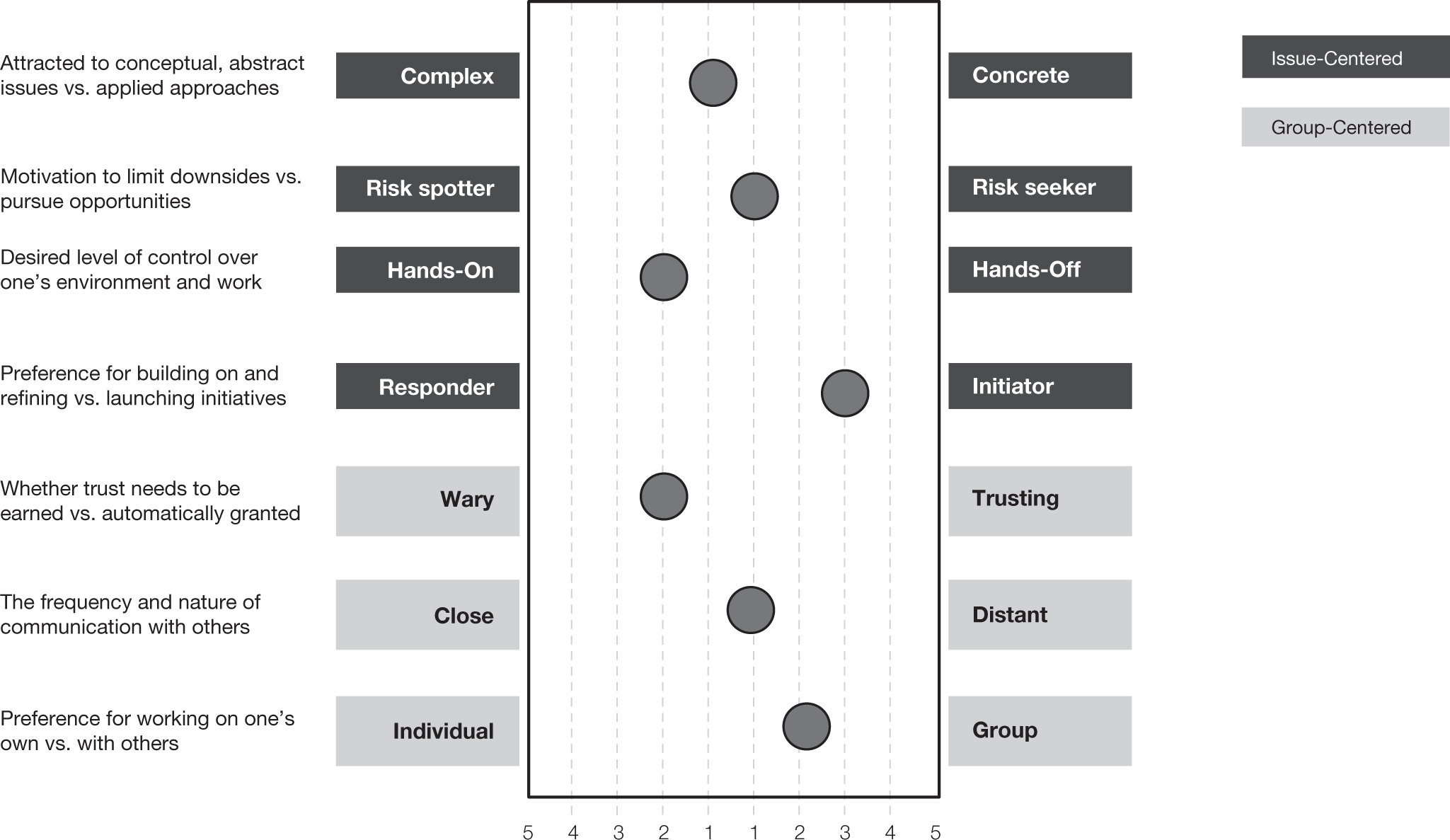

We have identified seven key behavioral dimensions, as summarized in Figure 4-1. The first four relate to the way a person tackles the issues on which the smart collaboration is focused. What kinds of problems is a given team member attracted to, and how is he or she inclined to tackle them? The next three relate to the group-centered behavioral components of smart collaboration—in other words, how the team member tends to interact with his or her peers in general.

Before we dig deeper into these seven dimensions, we should make it clear that when it comes to collaboration, none of these tendencies is inherently “good” or “bad.” They can all be strengths if used deliberately—that is, thoughtfully deployed to promote collaboration. But if your tendencies show up in the wrong way—for example, taken to the extreme when you’re under pressure—then they can block collaboration. As a rule, a winning team calls on a mix of these behaviors; conversely, the team that lacks such a mix may be headed for trouble.

FIGURE 4-1

The seven dimensions of smart collaboration

THE ORIGINS OF THE SEVEN DIMENSIONS

To understand the individual foundations of collaborative behavior, we pursued data on several fronts. First, we conducted a survey that involved respondents from more than fifty countries. This survey generated more than four thousand responses, which we assembled into a unique database—one that relies heavily on respondents’ answers to open-ended questions about their experiences of collaboration, including both actions that have helped them reap the benefits of collaboration and actions that have created barriers to collaboration.

At the same time, we spent two years digging deep into the reality of one specific workplace: a global organization with units across sixty-five countries. Through a series of diagnostics, interviews, observations, focus groups, and analysis of archival data, we identified a group of individual behaviors that help foster cross-silo collaboration, and a second group of behaviors that can impede collaboration. Whether done intentionally or not, acting in these anti-collaborative ways can encourage silos, reduce trust, and discourage people from working together.a

Bringing all the research efforts together, we developed a model of seven behavioral dimensions that are the foundation of the Smart Collaboration Accelerator psychometric tools, described later in the chapter.b

a. For more details on the surveys, interviews, and verification events we conducted to develop the seven-dimensional model, see “Part I, Quantitative and Qualitative Field Research: Core Behavioral Dimensions of Smart Collaboration,” in the technical report of the Smart Collaboration Accelerator, available on request through Gardner & Co. (https://

b. Details of the tool available through Gardner & Co. For early background research, see H. K. Gardner, “Teamwork and Collaboration in Professional Service Firms: Evolution, Challenges, and Opportunities,” in The Oxford Handbook of Professional Service Firms, ed. L. Empson et al. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 374–402; and H. K. Gardner, “Effective Teamwork and Collaboration,” in Managing Talent for Success: Talent Development in Law Firms, ed. R. Normand-Hochman (London: Globe Business, 2013), 145–159. Over time, we have revised and refined the model to crystallize the current seven dimensions and their relationships to specific aspects of smart collaboration.

For example, a consumer-products company we worked with had a strong bias toward recruiting Initiators and Complex thinkers. Why? The company’s leaders believed that the business needed people who were innovative and who could drive their teams to launch new products and solutions. As it turned out, their teams were indeed great at conceptualizing and jump-starting lots of projects, but without Responders and Concrete thinkers to move projects along, those products were slow to get to market. Those innovative teams were jumping ahead to the Next New Thing before the last good idea could be implemented. By using the framework, the manager was able to restructure the team with a stronger balance of skills.

Now let’s look at the seven dimensions in turn, beginning with what we call the “issue-centered” individual behaviors. We’ll do so from the perspective of an individual team member. How do you approach working with a group?

Issue-Centered Behaviors

The four issue-centered behaviors relate to the way a person tackles the issues on which the smart collaboration is focused.

Complex/Concrete

This dimension explains how you approach problems. Do you enjoy exploring abstract ideas and digging into ambiguous issues that have multiple causes? Do you draw on conceptual models and your past experiences to make connections across a range of topics, sometimes to the extent that the people around admit that they feel a bit baffled, or even put off? If so, you are on the Complex end of this spectrum.

Or, during a theoretical discussion, does your mind move ahead to questions like, How would we put this into action? What resources would we need? Or maybe even, So what? If so, you’re more on the Concrete side.

People with these two very different approaches can really get on each other’s nerves in a discussion. (Maybe you’ve been involved in such a fracas!) The Complex thinkers look down on their Concrete colleagues—They’re so mundane! So predictable!—while the Concrete thinkers grumble that all these abstractions floating in the air are a big waste of time, or a shameless exercise in grandstanding, or both. The truth, however, is that both approaches are essential for innovation. Why? Because innovation is more than just mere creativity. Creativity doesn’t qualify as innovation until it gets applied successfully.

Risk Spotter/Risk Seeker

Risk Seekers are the ones who examine a problem and instantly look for ways to turn it into an advantage or opportunity. Risk Spotters, by contrast, look at the same situation and see mainly downsides or even threats. The fear of failing is one dividing line between these groups: Risk Seekers will risk failure in pursuit of a perceived great opportunity; Risk Spotters will circle the wagons to head off the possibility of failure.

If you are a Risk Spotter, you are likely to be the one responsible for reality-checking new ideas. Yours can be a very positive influence—for example, by helping the team avoid being overly optimistic and stay out of the trap of group-think. But it’s incumbent on you to be a constructive skeptic. Yes, point out the risks, but also be ready with solutions. To meet one CEO who learned to turn his Risk-Spotting tendencies into a strength by partnering with a complementary chief operating officer (COO), see the sidebar.

If you’re a Risk Seeker, you’re in a good position to help the team manage the inevitable setbacks, put those failures in a broader context, and keep the team focused on the goals. Encourage the discussion of challenge and risks—even if that’s not your default mode—and don’t react emotionally if people challenge your ideas. Remember: smart collaboration requires differing perspectives.

Hands-On/Hands-Off

Which is better for promoting collaboration: being Hands-On or Hands-Off?

It’s not a trick question, but neither does it lend itself to an easy answer. Hands-Off people give others lots of room to operate independently, but at the same time, they may fail to give sufficient guidance and feedback. In a remote-work context, moreover, the truly Hands-off team member runs the risk of simply … disappearing. Hands-on people, meanwhile, are likely to give clear direction and coaching, and are unlikely to drop out of sight. But when stressed, they tend to roll up their sleeves and get the job done themselves. Taken to an extreme, the result is micromanagement, or even the exclusion of other team members.

COMPLEX THINKER, RISK SPOTTER

Markus, a C-level executive with a global beverage company, had a rocky start in his position. Although he had strong ideas about solving production challenges in the early days of the pandemic, he had never reached the point of making a single recommendation to the company’s board. One stumbling block: Markus constantly obsessed about all the pieces that could go wrong, as he saw it.

His fortunes started to change when he got to know the company’s new COO, a natural Risk Seeker and a more Concrete thinker. With the COO as his sounding board, Markus realized how his efforts to mitigate all possible risks became a roadblock to his conceptually powerful solutions. The way the COO framed the same situation opened Markus’s eyes to the wide range of potential upsides, as well the risks. By embracing those different perspectives, Markus’s ideas were able to be captured in well-rounded, compelling proposals that were welcomed and valued by the board.

Many people locate themselves in the middle of the spectrum along this dimension. If you’re one of them, it’s worth reflecting on when you’re more likely to be Hands-on or Hands-off. For example, make sure you’re not instinctively jumping in to “help” the team member who happens to have a strong accent. Also be aware of the unintended (and maybe unwelcome) consequences of Hands-on behavior. If your colleagues come to anticipate that kind of behavior from you, they may be inclined to sit back and wait for you to set out the action plan on your own: the opposite of smart collaboration.

Responder/Initiator

Who goes first, and who goes second?

If you’re strong along the Initiator dimension, you’re always looking ahead to spot future problems or opportunities, then working proactively to shape them.

If you’re a Responder, by contrast, you’re comfortable with not being the first mover. “Going second” gives you the chance to build on others’ initiatives, perhaps helping to take them from being unworkable to viable. And if you’re an effective Responder, you can be counted on to carry the work through. Your willingness to pitch in and support new initiatives is a boon to teams. Along the way to the larger solution, you react to actual problems, rather than wasting time caught up in what-ifs.

A word of caution to the Responder: Make sure your contributions are recognized and valued. In many organizations, it’s the Initiators who get the glory (think about the “heroic” deal makers whose teams never get any credit for doing the hard work of executing). And while it’s fine for them to get their due, make sure to use ongoing group communications to build a suitably broad base of ownership for success—and share those comms as broadly as possible.

Now let’s look at the four group-centered behaviors.

The Group-Centered Behaviors

The three group-centered behaviors relate to how the team member tends to interact with his or her peers.

TWO RESPONDERS AND AN INITIATOR

The three presidents of an international mobility technology company are peers, with each leading a division. Despite the company’s siloed business approach, the three leaders have developed strong bonds through a combination of leadership meetings, calls, and offsites. During one of their conversations, President 3 proudly reported on her team’s favorable reputation: “When folks have an idea and want to get it done, they come to us. We are brilliant closers.” President 1 chuckled and said, “Ditto!” Both leaders had figured out how to leverage their strengths as Responders.

President 2 laughed too, but she was intrigued. She wanted to understand their “secret sauce” for finishing new projects. As a high-powered Initiator, she often found herself exploring forward-looking ideas, but far less often saw her team carry those idea across the finish line.

On the advice of her peers, P2 expanded her collaborative network to include more colleagues who could help shepherd her product development to completion—a group that included both P1 and P2.

Wary/Trusting

When you meet new colleagues, do you assume that they have a high degree of integrity and are fully capable of doing their jobs? Or do you take a “wait-and-see” approach, extending your trust only after your colleagues have proved themselves? If you are in the Trusting category—that is, if you’re the kind of person who assumes that your colleagues are often right and generally have good intentions—you may jump fairly quickly into collaboration. If you are more Wary—tending to rely on data and evidence to assess whether others are really up to the job and are in roles that play to their strengths—you may get to collaboration more slowly.

HIGH TRUST AND HANDS-OFF: WHAT COULD POSSIBLY GO WRONG?

We recently worked with the leader of a team handling the rollout of a new 5G-related technology for a major telecoms company. Here, we’ll call her Ann.

At a point when they were well along in that project, Ann had a major lightbulb moment: Based on her Smart Collaboration Accelerator results (a tool detailed later in this chapter) and discussions with a coach, she learned that she was both highly Trusting and highly Hands-off. Because she trusted in people’s competence, she instinctively believed her team members could handle the major stretch assignments they were taking on. But because she was also inclined to be Hands-off, she rarely gave those colleagues any effective direction or coaching. She was surprised and frustrated that they frequently were coming back with solutions that were different from what she had envisioned. Masking that frustration, she’d say, “Well, this isn’t quite right. But obviously you guys are great at what you do, so why don’t you give it another try?”

In other words, she was failing to provide concrete feedback on what she was looking for, or how to approach the problem differently. Instead of empowering the team members who were reporting to her—which was her natural inclination—she was actually putting them in a position of having to read her mind. Yes, the team appreciated her trust and their resulting autonomy, but on balance, it wasn’t working. She had taken her behaviors too far.

Ann realized that she needed to try a different approach—one more focused on ensuring that she and her teammates were aligned on the vision for projects, that they would all be open to thought-partnering as the work progressed, and that she was giving more frequent coaching and direct feedback.

For the innately Trusting, use your high trust level to welcome new viewpoints onto your teams and thereby increase the diversity of thought. This might involve welcoming someone in as a regular contributor—or even as a one-off—to share a new perspective and enrich the group’s thinking. Remember that those around you may be more Wary and you may need to moderate your enthusiasm to earn their trust.

For the Wary among you: listen to those Wary tendencies! Your skeptical eye—whether it is focused on people, organizational politics, or commercial situations—can help spot small issues before they become more substantial ones. Early detection and correction can enhance trust by letting people know that it’s safe to admit errors and that their colleagues will support them. Meanwhile, be careful not to appear overly negative, argumentative, or unsupportive of others.

Close/Distant Communicator

This dimension focuses on communication style. Let’s imagine one colleague of yours who always gets right down to business, with no preliminaries. One result of this approach is that you may not know anything about this colleague’s personal life, despite the fact that you’ve worked together for years. People like this are what we call Distant. They engage when they need to push work forward but not for socializing. They tend to be hard to read. You frequently feel like you don’t know where you stand with them.

Now let’s conjure up a Close colleague. He or she is the person who injects energy into a meeting, frequently drops by your office, shares a photo of the kids, discusses plans for the weekend, and seems quite comfortable with being “easy to read.”

Both Distant and Close communicators can be powerful collaboration boosters. If you are more Distant, you can use that as a strength to let others have more visibility and more of the limelight. (Generally, though, you do need to open up enough to ensure that colleagues can figure out what’s on your mind.) If you are a Close communicator, you most likely have a relatively large network of active relationships. This means that you can be a powerful connector—helping others build their own networks and welcoming those kinds of people (such as new arrivals or members of formerly underrepresented minority groups) who might otherwise find it hard to get tied into the organization.

Individual/Group

Where do you fall on the spectrum of preferring to work as part of a group as opposed to working independently?

HIGHLY CLOSE

Jeffrey, the new president of a large, public university, was hired to design and implement a top-to-bottom turnaround effort. Part of the problem, he was told, was its uncollaborative culture. Tensions ran high, and key performance indicators kept sinking.

Given the seriousness of the issues, Jeffrey—hired in part because he had a reputation for being collegial, “super friendly,” and personable—adopted a task-oriented, rigorous, Distant leadership style that he felt was better suited to the task at hand, reinforcing the notion that he meant business.

It didn’t work. While his plan was acknowledged by most to be spot-on, he struggled to get people engaged and progress was minimal. Jeffrey’s increasing challenges led to a series of deep, reflective talks with a few trusted advisers. Based on these talks, Jeffrey realized he had abandoned his strengths and tried to lead in a way that was not authentic. Once he embraced his natural, warm self, the organization responded swiftly, and the turnaround began.

A highly Individual person prefers to work on their own and be self-reliant. Drawing on our own experience, we have a seriously Individualistic colleague who sees collaboration as inefficient, even describing it as a “tax”—something that occasionally may be necessary but is generally unwelcome and expensive. Other colleagues, conversely, gravitate toward team meetings. They love the energy of being with others and solving problems by sharing and debating ideas. They are what we call Group oriented.

The challenge for the highly Individual person is to make a conscious, and fair, assessment of when group work is worth it and when independent work is likely to be more effective. In our experience, even the most hardboiled Individual eventually admits that certain complex projects benefit from the wisdom of others—just as die-hard collaborators admit that some relatively uncomplicated tasks are best performed as solo efforts.

INDIVIDUAL

Sujin, the CEO of a global software giant, was surprised to learn that her reputation across her team and the larger executive branch was that she “just doesn’t care” and “doesn’t participate.” As a deeply passionate leader who wakes up in the morning determined to make every day count, Sujin couldn’t understand where these assessments were coming from. She thoroughly prepared for each of her meetings and always arrived at them with at least one well-thought-through plan that the team could use as a springboard. She felt she was a valuable contributor to the team’s work—so where were these negative perceptions coming from?

Sujin’s blind spot was not understanding how colleagues interpreted her frequent “disappearances.” For example, while others extended kick-off meeting debates throughout lunch “just to keep thinking aloud together,” Sujin retreated to her office to organize her thoughts and push her own thinking. Why? She felt that until she had put in enough solo thinking time, group discussions were time poorly spent, for her.

The change began when Sujin started openly disclosing why she “disappeared”—it was not to be anti-collaborative but rather to think deeply. This transparency helped the team understand her natural way of getting started, especially when it came to topics that really mattered to her and her department.

In contrast to the individual, the highly Group-oriented person can be a visible role model for collaborative behavior. Actions like sharing speaking time, actively listening, encouraging colleagues to contribute (especially the Distant communicators), soliciting input from experts around the organization, and focusing on execution help develop a positive group climate.

As we said earlier, none of these three behaviors is necessarily hostile to, or at odds with, collaboration. By extension, no single type of person is best at collaboration. Perhaps this seems counterintuitive. Wouldn’t the best collaborator be the charismatic networker who lights up a room? Not necessarily: research shows that people who are more private have an advantage at intellectual problem-solving. Susan Cain, author of Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking, found that introverts sit still more, reflect more, and are more reserved, making them knowledgeable about many subjects and appropriately slow to process decisions.1 Because collaboration requires genuine listening (not just waiting for your turn to make a point!), a person with a strong individual tendency can be a great collaborator.

Conversely, isn’t a highly Wary person going to be uncollaborative? Again, not necessarily. Imagine a team that’s stacked with highly Trusting people. They assume that everyone is trustworthy and competent. But what if that’s not uniformly true? A Wary person asks questions like, Does our negotiating partner truly have a win-win mindset? If not, does that argue for us taking a new approach to these negotiations? Does our team have the skills required to negotiate in some new way?

The consumer-products company mentioned earlier ultimately addressed its execution issues by restaffing its teams with a mix of Responders, Initiators, and Complex and Concrete thinkers. It then took steps to ensure that the members of the teams understood their colleagues’ strengths, and to encourage those people to be their authentic selves, even in the face of conformity pressure.

A final thought to close this section: everyone has natural tendencies, as just outlined, but not everyone is extreme, or even fixed, in those tendencies. Suppose that you show up in the middle of one of the spectrums we’ve just described. That doesn’t necessarily mean that you are “average” in your outlook and instincts. Instead, it may mean that you’re more likely to flex in response to a given pressure-filled situation: sometimes you’re this, and sometimes you’re not this.

This sort of flexing can be a good thing—and even critically important in a team context. The key is to flex intentionally. What’s the pressure we’re under? What do I know about the strengths of the people around me, as they come under pressure? How can I complement their strengths by playing up one of my own?

To answer these kinds of questions—and to locate yourself along the seven dimensions we have described—you may find the tool we describe in the next section to be helpful.

Accurately Identifying Your Own Behavioral Tendencies

How do you figure out what your strengths really are, and how do you tap into them? We emphasize “really” because it’s not a question of how you’d like to be seen. (We all have an idealized self-image that we’d like to live up to, but often don’t.) Instead, it’s a question of how you are likely to behave, especially under the pressures of a work environment. What are your natural tendencies—and how can you use them intentionally, so they can serve you as strengths?

The best way to learn about your behavioral tendencies is to use a psychometric test.2 Through this kind of assessment, people discover their underlying, natural behavioral styles. These research-based insights can be essential, because so many of us have blind spots about how we actually operate at work. Removing the blind spots sets us up to be more effective collaborators.

We’ve developed a psychometric tool that focuses specifically on the seven dimensions described here, and which we call the Smart Collaboration Accelerator.3 Based on research with thousands of participants in organizations around the globe, the Accelerator psychometric helps people use their strengths for smarter collaboration. The test itself is simple enough: an online self-assessment, requiring only about ten minutes to complete, at the end of which you receive a report showing your profile. For teams, multiple individual profiles can be compiled into a team profile providing insights into the behavioral dynamics of the group.

Then what? The online report not only reveals your profile but also provides personalized recommendations about ways to turn your natural tendencies into concrete behaviors that can foster collaboration—and ways to avoid having your strengths hinder collaboration. In our work with people ranging from senior executives of global corporations to junior lawyers and software engineers, we have found the data generated by these tools to be powerful—especially for those kinds of people who think of themselves as rigorous and data driven.

Let’s assume that you have your test results, including some recommended strategies, in hand. What’s next? Your overall goal here is to turn your potential strengths into actual strengths, which will allow you to be a better collaborator and also help bring out the best in the people around you. To some extent, you can undertake this challenge on your own. You might set interim goals for yourself, and also set target dates for peer feedback on your progress—for example, a 360 feedback exercise a year from now.

But as we noted at the opening of this chapter, nobody collaborates alone. Much of the necessary work is likely to take place in the team context: the subject of our next section.

Understanding and Using Collaborative Strengths on the Team Level

Differences are powerful.

All too often, discussions of diversity trivialize or diminish that power. When we advocate for smart collaboration on teams, it’s not because we believe that people should be tolerant of those who are different from themselves—although certainly we do believe that. Instead, it’s because the right diverse team, managed adeptly, can get things done that neither the solo contributor nor the homogeneous team can accomplish.

In this section, let’s take the team leader’s perspective. As indicated earlier, a useful first step is to do your own homework. What does your personal profile tell you about your leadership style and its impact on collaboration? The earlier sidebar describes a telecoms company team leader, Ann, who learned some important lessons about herself and adjusted her team-leadership style accordingly.

Let’s assume that you’ve received not only your own profile but also an aggregate psychometric profile of your team, with individual but anonymous profiles sketched out and quantified. (In other words, you know that you have a certain number of Responders and a certain number of Initiators, but you don’t know who they are, based on the assessment results.) What now?

First, focus on the distribution of strengths, rather than averages. (Averages wash out the diversity that you’re trying to draw on.) Next, hypothesize about how any imbalances in that distribution might be hindering the team’s work. Then look for evidence that this may actually be happening. We worked with one global renewable energy company in which the thirty-five most senior executives were massively skewed toward Risk Seekers. This revelation, in turn, helped surface an uncomfortable truth: the team was regularly steam-rolling its five members who were trying to inject doses of realism into their group discussions. What was most interesting about this sequence of events was that most participants knew the problem was real and important—but most were engineers, who needed to see the supporting data.

Some of the most powerful changes happen in a group when the team members can see how their own profiles fit in with those of their colleagues. When team members understand their overall composition, they are far more likely to seek out the strengths of others—for example, calling on a Complex thinker to help break down and explain a vexingly ambiguous issue. That’s the end goal. So what practical steps can you as a team leader take to get there? Here are some suggestions:

- In the context of a facilitated workshop, kick off a candid discussion of strengths. What is the profile of the team? Do we have gaps in our profile? Is there a dominant profile along one dimension and an individual outlier whose voice we need to hear? How can we use the strengths of each individual to drive forward on our goals? Note that this is important not only for new teams but also for stable teams, on which assumptions about skills and experience can be seriously out of date.4 How much do we know about our colleagues’ past experience, whether in prior roles, companies, outside work, education, or even a relevant hobby? How might that experience come to bear?

- Also in the group setting, encourage people to reflect on their preferred ways of working—both in routine interludes and at times of crisis.5 Note that we’ve called for a “facilitated” workshop. If you’re not confident that you have the skills to run such a workshop on your own, get help. There are skilled coaches out there who can take the pressure off you and thereby increase your chances of success.

- Either independently or in consultation with other team leaders and your superiors in the organization, assess your team’s gaps. Are additional experiences and perspectives needed? If the answer is clearly yes, how and when will those resources be acquired?

- Meanwhile, allocate tasks to strengths—and consider deliberately defining “stretch” responsibilities for people who appear to have the potential to rise to new collaborative challenges. If you are a Hands-off leader, make sure someone is there to help the stretched individuals—for example, the coach or a Hands-on colleague.

- Throughout this change process, maintain an environment of transparent feedback and constructive challenge. This should happen through both one-on-one huddles (“Are you leveraging your strengths?”) and team meetings (“Are we leveraging our strengths?”).

Getting and Keeping the Great People

Once again: addressing truly complex problems requires integrating the collective wisdom of individuals with diverse expertise and experiences and allowing them to play to their own strengths—or in slightly different terms, to engage with their work as their “authentic selves.” Research confirms that when people believe that they can put their own strengths to work, both they and their company wind up performing better. This is true across a wide range of dimensions, including customer satisfaction and employee retention.

The converse is also true. When people are expected to fit into the prevailing work culture, rather than acting authentically, performance declines. They’re unhappy, and unhappy people tend to leave organizations at higher rates. The pattern is particularly clear among people of color and other underrepresented groups, whom in many cases companies are trying very hard to recruit and retain.6 But it also comes to bear on “diversity” more broadly defined—and here’s another place where understanding and using collaborative strengths can help. We recently sat in on a company’s LGBTQ training, during which a team member who had recently gone through two smart collaboration workshops said, “I honestly can’t understand the lifestyle, but I do understand that getting different perspectives is valuable and we will be better when everyone in the team can contribute their perspectives.” The Smart Collaboration Accelerator training helps people understand the importance of leveraging behavioral differences and allows them to reapply that way of thinking to other kinds of differences as well.

Our next chapter explores the challenges of integrating talent—both those new joiners whom you hire on their own and those who join as part of an acquisition—and how a focus on smart collaboration can help.