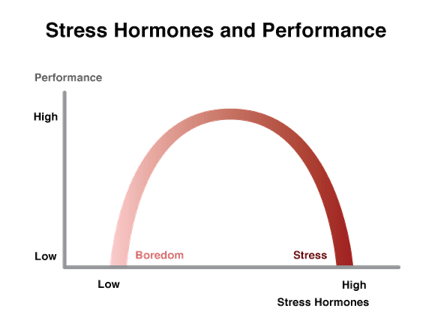

AN UPSIDE-DOWN U

Plotting the relationship between mental adeptness (and performance generally) and the spectrum of moods creates what looks like an upside-down U with its legs spread out a bit. Joy, cognitive efficiency, and outstanding performance occur at the peak of the inverted U. Along the downside of one leg lies boredom, along the other anxiety. The more apathy or angst we feel, the worse we do, whether on a term paper or an office memo.

We are lifted out of the daze of boredom as a challenge piques our interest, our motivation increases, and attention focuses. The height of cognitive performance occurs where motivation and focus peak, at the intersection of a task’s difficulty and our ability to match its demand. At a tipping point just past this peak of cognitive efficiency, challenges begin to exceed ability, and so the downside of the inverted U begins.

We taste panic as we realize, say, we’ve procrastinated disastrously long on that paper or memo. From there our increasing anxiety erodes our cognitive efficiency.55 As tasks multiply in difficulty and challenge melts into overwhelm, the low road becomes increasingly active. The executive center frazzles as the challenges engulf our abilities, and the brain hands the reins to the emotional centers. This neural shift of control accounts for the shape of the upside-down U.

An upside-down U graphs the relationship between levels of stress and mental performance such as learning or decision-making. Stress varies with challenge; at the low end, too little breeds disinterest and boredom, while as challenge increases it boosts interest, attention, and motivation – which at their optimal level produce maximum cognitive efficiency and achievement. As challenges continue to rise beyond our skill to handle them, stress intensifies; at its extreme, our performance and learning collapse.

The inverted U reflects the impact of two different neural systems on learning and performance. Both build as enhanced attention and motivation increase the activity of the glucocorticoid system; healthy levels of cortisol energize us for engagement.56 Positive moods elicit the mild-to-moderate range of cortisol associated with better learning.

But if stress continues to climb after that optimal point where people learn and perform at their best, a second neural system kicks in to secrete norepinephrine at the high levels found when we feel outright fear.57 From this point – the start of that downward slope toward panic – the more stress escalates, the worse our mental efficiency and performance become.

During high anxiety the brain secretes high levels of cortisol plus norepinephrine that interfere with the smooth operation of neural mechanisms for learning and memory. When these stress hormones reach a critical level, they enhance amygdala function but debilitate the prefrontal areas, which lose their ability to contain amygdala-driven impulses.

As any student knows who has suddenly found himself studying harder as a test approaches, a modicum of pressure enhances motivation and focuses attention. Up to a point, selective attention increases as levels of pressure ratchet upward, like looming deadlines, a teacher watching, or a challenging assignment. Paying fuller attention means that working memory operates with more cognitive efficiency, culminating in maximum mental ease. But at a tipping point just past the optimal state – where challenges begin to overmatch ability – increasing anxiety starts to erode cognitive efficiency. For example, in this zone of performance disaster, students with math anxiety have less attention available when they tackle a math problem. Their anxious worrying occupies the attentional space they need, impairing their ability to solve problems or grasp new concepts.

All of this directly affects how well we do in the classroom – or on the job. While we are distressed, we don’t think clearly, and we tend to lose interest in pursuing even goals that are important to us. Psychologists who have studied the effects of mood on learning conclude that when students are neither attentive nor happy in class, they absorb only a fraction of the information being presented.58

The drawbacks apply as well to leaders. Foul feelings weaken empathy and concern. For example, managers in bad moods give more negative performance appraisals, focusing only on the downside, and are more disapproving in their opinions.59

We do best at moderate to challenging levels of stress; while the mind frazzles under extreme pressure.