4

Monitor Results and Revise

Things change; organizations change; the environment changes; leadership changes; the economy changes. Risks themselves change. As a result the organization must periodically evaluate the efficacy of the risk treatment techniques it is utilizing with critical risks. Are they still working or must they be revised? Secondly, new risks can become important and risks that were previously considered to be non-critical may be critical. Critical risks on the priority list may rise and fall in importance and impact over time. Assurance, audit, review of data, and periodic reassessment of the risks to strategy are steps that cannot be overlooked. The strategy itself must be reconsidered when necessary.

4.1 BUSINESS ETHICS AND RISK MANAGEMENT

Marc Ronez

Chief Risk Strategist and Master Coach, Asia Risk Management Institute

“It's only when the tide goes out that you learn who's been swimming naked.” (Warren Buffett, Berkshire Hathaway)

A string of economic crises (the Asian financial crisis, dot-com bubble and the subprime collapse) as well as major corporate collapses (Enron, WorldCom and many others) have put the issue of business ethics under the spotlight and made it top item on the “To Do” list of boards of directors all around the world. The reason for this increased scrutiny is simple: At the root cause of most corporate collapses and economic crises, you will find an ethical issue that had not been properly addressed.

For example, many corporate scandals of the 1990s and 2000s were the result of companies trying to evade regulatory rules to either hide problems (creative accounting to take losses out of the balance sheet, e.g. Barings (1995), Enron (2001)) or to do something they were not supposed to do (bribery, abuse of power, e.g. Marsh (2004), BAE systems (2010)).

And each time, regulators around the world reacted in a typical fashion by enacting new laws with the aim to prevent such behavior from repeating itself. Unfortunately more rules and controls like the ones enforced by Basel II or SOX have proven to be little help to resolve the problem. On the contrary, it appears that smart people in organizations found different even more creative unethical ways of dealing with regulatory constraints as in the case of the subprime market bubble and subsequent collapse.

Hence in today's global and uncertain world, where the collapse of major corporate players and/or the next financial bubble might lead to a systemic collapse of our financial system and world economy, the apparent lack of ethics in the business world is a crucial issue that needs to be addressed effectively.

4.1.1 Defining What Business Ethics Is

Ethics refers to the moral philosophy, values and norms of behavior that explain and guide an individual's behavior in society. Ethics as a system forms a moral code of conduct, a sort of compass that helps people in differentiating what is right or wrong, what is good or bad.

To be considered of good character, i.e. displaying good ethical behavior, it is generally understood that you need to take into account and live up to a set of moral principles such as:

- Dignity: refers to treating each individual with respect.

- Equity: is just being fair and even-handed in decisions.

- Prudence: think and prepare carefully before you do something.

- Honesty: is being straightforward and truthful.

- Transparency: is about not concealing that which should be revealed.

- Goodwill: concern for others, kindness and tolerance.

- Integrity: when we say we do something, we will do it.

- Spirit of excellence: always trying to do our best.

This list is by no mean exhaustive and just highlights some of the key moral principles that should be used as a guide when making decisions.

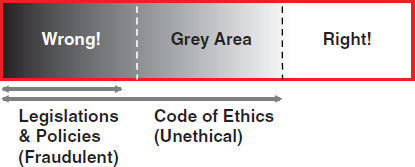

Business ethics refers specifically to those moral principles and rules of conduct that are governing the business world and activities. To support effective compliance, many of these principles and rules have over time been formalized into legal rules embedded in various regulatory frameworks. As a matter of fact the rule of the law is a key force unifying and controlling corporate behavior within society and the entire body of rules is based explicitly or implicitly on ethical principles. The purpose of the law when it comes to ethics is to enforce certain minimum standards of ethical business practices in the business world. This is also the limitation as, most of the time, regulatory rules merely specify the lowest common denominator of what can be accepted by all the parties involved, as illustrated by the intense negotiation and lobbying that surrounded the development of the Basel III accords. This means that typically, legal requirements will lag behind moral expectations of what would be considered as an unethical behavior as illustrated in Figure 4.1. For example, in many industries, it has been common advertising practice to make exaggerated claims about the quality and effectiveness of the products and services offered. While those practices may be unethical, as long as there are no laws against them, they are legal. Furthermore, it is a continuously evolving situation as new laws are enacted all the time and what is legal today may not be legal tomorrow.

Figure 4.1 Illegal vs. Unethical.

This time-lag problem cannot be resolved as the continuous development of new technologies and products as well as the ever-changing expectations of stakeholders will give rise to new ethical issues and questionable practices that will not have yet been addressed by the current body of legislation. It must also be noted that the same practices may be legal in one country but illegal in another where the laws have expanded faster to cover the issue. This adds another level of complexity in managing compliance and ethical risk issues.

Hence it is clear that ensuring ethics cannot be achieved by merely complying with the law. Organizations must look beyond and seek to understand how the ever-changing moral expectations of their stakeholders may affect an organization's ability to create value.

4.1.2 Business Ethics: “Good to Have” or Business Imperative?

In today's world, business leaders talk a lot about “ethics” and “values”. When speaking publicly about their organizations, they will usually stress the important role of corporate values in the success of their business. To be fair, a lot of visible efforts have been undertaken to develop “values statements” as well as embed moral principles and rules into codes of conduct supposed to guide the behavior of the employees in organizations. Hence it is extremely ironical to observe that despite all the talking and actions, we can generally observe that very few organizations have made any real improvements in their actual ethical practices. It actually seems that the more business leaders talk about ethics, the less they practice it. In other words, the business ethics efforts are more about form than substance. Abraham Lincoln, 16th USA President highlighted this gap when he famously declared:

“Character is like a tree and reputation like its shadow. The shadow is what we think of it, the tree is the real thing.”

It seems that business leaders care more about the “shadow” appearing to be good than about the “tree” to really be good. So while most people will pay lip service to the importance of ethical principles, the reality is that, unfortunately, ethics is often considered as a “good to have”, something of a “luxury” in the fast-paced turmoil of today's volatile business environment. Modern organizations are indeed operating in an environment characterized by multiple pressures: a constant pace of change, continuous pressures on both revenues and earnings, where the share price is “king” and where the average life expectancy of a CEO is continuously reducing. Hence it may not be so surprising that in some companies, the top management can lose sight of the right course of actions by focusing on short-term opportunities at the expense of longer-term impacts and needs. In this context, business ethics will be obviously perceived as an impediment to doing business. Of course, the subprime crisis and the many corporate collapses making headline news are strong reminders of the fundamental need for stronger ethics, risk management and regulatory compliance practices. As usual, after those events, regulators around the world have responded once again, with landmark legislation with the aim to raise the standards of business ethics in the industries considered.

Benefits of Business Ethics and Cost and the Lack of It

Ethics is not important merely because the law says so. It is not just a question of legal compliance and you do need to care about the rest. In fact, letting stakeholders develop the perception that ethical behavior is not important to an organization will be incredibly damaging to its reputation and business prospects. More than just a public relation talk, a breach of ethics when exposed will result in wide range of negative direct and indirect consequences for an organization such as negative media coverage, regulator investigation, customer boycotts, reduced share price, drop in revenue and profitability, loss of key staff, even possibly criminal investigation and imprisonment for the executives involved. This, of course, applies equally for individuals, and there are plenty of cases of highly talented and successful individuals who were castigated because they violated ethical and legal requirements.

Conversely, good ethics is also good business. Treating stakeholders ethically will have direct impact on organizational performance by providing the following benefits:

- Build a solid reputation providing a differentiator edge in competitive markets.

- Attract consumers and have them buy products/services at a premium price.

- Attract investors and secure capital at a lower cost.

- Recruit and retain high-quality employees.

- Be recommended as a good partner.

- Nurture a positive relationship with regulators and the media.

- Provide protection against crisis by receiving the benefit of the doubt from loyal customers.

Anita Roddick, the founder of Body Shop is often cited (The New York Times, 2007), as an example of how doing good things is good for business. She has built a business model around developing quality beauty products that did not involve testing on animals and was the first to introduce “Fair Trade” to the cosmetic industry. By this strong ethical stance, she won the support of a growing number of more ethically and socially conscious customers.

The Emergence of the CSR Agenda: A New Moral Code of Conduct for Doing Business?

This leads us to another reason why business ethics is essential for business: the emergence of corporate social responsibility (CSR). CSR is about seriously considering the impact of an organization's activities on society. It requires organizations and their staff to consider the impact of their actions in terms of a whole natural and social system, and holds them responsible for the effects of their actions anywhere in that system. It could also be the impact on the natural environment or the communities living there.

In recent years business has been viewed increasingly as a major cause of social, environmental and economic problems. Organizations, especially commercial companies, are widely perceived to seek short-term profits for themselves at the expense of the broader community and future generations. It seems that in their pursuit of short-term profits, too many companies overlook the well-being of their customers, the depletion of natural resources vital to their businesses, the viability of key suppliers, or the economic distress of the communities in which they produce and sell.

CSR proponents advocate that this narrow view of value creation prevailing in many companies seeking to optimize short-term financial performance while essentially ignoring the broader influences that determine their longer-term success is not sustainable. It will ultimately lead to the collapse of the companies following that model and tremendous cost to society as a whole.

Furthermore as the standards for ethical behavior continue to evolve and increase, your company's key stakeholders – shareholders, clients, employees and others, will increasingly expect you to meet or exceed those standards. This is true to various degrees in most industries today. While the value creation objective of organization is well understood and accepted, it cannot be achieved by ignoring basic ethical norms, values and standards of business practices. Companies get their “official” license to operate from the regulators, but also get an “unofficial” license to operate from their other stakeholders and the wider public. Therefore it is important for organizations to meet public expectations through proactive compliance with ethics codes, industry practices, and developing CSR-based business models.

4.1.3 ERM: A Rules or a Values-Based Approach?

Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) has emerged over the past 15 years as a “new paradigm” for managing holistically the portfolio of risks that organizations face in today's global and uncertain environment. Riding on the wake of numerous crises and corporate collapses, ERM concepts, tools and practices have gradually invaded both private and public organizations including governments all over the world. Evidence for this development can be found in the number of articles, books, and guidelines published on the subject (COSO, ISO 31000) as well as in policy and regulatory development over the past 10 years (Basel II, III, Sarbanes-Oxley, and many other regulations). The rise of risk management has been so spectacular, that Michael Power, in his book The Risk Management of Everything (2004) describes it as an “explosion of new risk control practices resulting from emerging social and political pressures aiming to manage everything” that could potentially go wrong. It is quite natural to understand that economic crises and corporate scandals have typically resulted in the creation of more rules in an attempt to prevent such behaviors repeating themselves in the future. It is to be expected that industry players and policy makers will continue to focus more and more on mechanisms to improve corporate governance, ethics and risk management.

But is it the right approach? There is a danger with continuously adding new layers of rules and controls. The problem is that it will drive to a defensive risk management approach in organization. To be controllable and manageable, risks must be made measurable, auditable and governable. Hence, many risks have been operationalized as organizational processes of control. Such systems translate primary or real risks into systems risks with focus on rules, compliance and warning mechanisms. Ironically, this approach will ultimately be detrimental to ethics and risk management as people will find a way to hide behind the system to avoid being responsible and accountable as was exemplified during the subprime crisis where the poor quality of the primary risks, i.e. the NINA (no income, no assets mortgage loans) were ignored because the risks had been repackaged and securitized, hiding their true nature behind clever packaging and the inherent human greed and blindness to risk. Solely adding controls does not deal the real issue, which is the importance of the human factor.

To make it short, the effectiveness of enterprise risk management cannot rise above the integrity and level of ethical values of the people who create, administer, and monitor an organization activity. Ethical values are by definition, essential elements of an organization's internal environment, affecting the design, administration, and monitoring of other enterprise risk management components. No matter how well designed and “strong” a risk management system may be, smart people will always find loopholes, a way to cut corners or go around it. It is just a question of time. Therefore to support good and effective risk management practices and achieve core objectives, an organization corporate culture must have integrated important key ethical values. If it has not done so, while the organization may appear in the short run to be successful, poor performance and ultimately failure is inevitable.

Beyond the diversity of values in organizational cultures, ERM is based on and promotes a values system that will require people to:

- Think in terms of shared value and sustainability.

- Act with integrity and discipline.

- Be responsible and accountable for what they do.

- Be honest and transparent about how they do things.

- Share information and knowledge proactively.

This is not an exhaustive list but the above values are some of the most important moral principles on which a strong and effective ERM system can be built. Reading the above list also explains why it is difficult to implement ERM effectively as those values are in contradiction with many management practices in today's modern organizations. Nevertheless, in the wake of the recent financial crisis and corporate collapses, ERM is a rapidly evolving discipline that places ethical values at the heart of good governance, risk management and compliance.

4.1.4 Building Ethical Risk Management in Organizations

To address the legal, ethical, social responsibility and environmental risks they face, organizations should design and implement business ethics risk management programs. This is not just about the system, it is actually primarily about the people and the culture of the organization considered. An organization's objectives, strategy and the way they are implemented are based on preferences, values, judgments and management styles. Management's integrity and commitment to ethical values influence these preferences and judgments, which are translated into standards of behavior. Leaders and managers of well-run organizations increasingly understand that ethical behavior is good business. If so why do unethical behaviors still seem to be so prevalent in many organizations? Organizations should create an environment both in terms of culture and system where ethical behavior is encouraged while unethical behavior is prevented and punished. To do so it is necessary to understand first what constitutes unethical behavior and how it can happen in organizations.

How Unethical Behavior Can Happen in Organizations

Every day, managers are confronted with risks in any activities they undertake. And every day, they may have to make decisions about what they are going to do about those risks. Some of those decisions are simple while others can be particularly difficult to make. In the pursuit of short-term profits to achieve their bonus targets or for many other reasons, managers can sometime lose sight of what is right or wrong. Business ethics problems can involve any of the following issues (this list is not exhaustive):

- Bribery in the private and public sector of contracting officer.

- Money laundering.

- Improper sales and marketing practices (misleading or exaggerated advertising).

- False financial accounting.

- Environmental irresponsibility.

- Breach of privacy.

- Insider trading.

- Use of child labor.

- Tax evasion.

- Improper competition practices.

- Unfair labor practices.

- Counterfeit goods.

- Breach of copyright.

- Industrial espionage.

Facing and Resolving Dilemmas

At the core of many difficult decisions about personal or business issues, there is some sort of dilemma. A dilemma can be defined as a difficult choice with no simple easy solution. For example you might have received two job offers. The first one is exactly the kind of senior marketing position you were vying for and comes with a great salary but it is with a tobacco company and selling a product that slowly kills people is against your principles. The second offer is from a small company and the job scope is fine but the compensation package is very unattractive for you. You have been looking for a job for more than a year now and those are the only two offers available and due to financial constraints, you cannot afford to wait any longer. You are in situation requiring you to make a choice between equally undesirable or unfavorable options. Which one will you take?

A dilemma will put managers in an exposed position, as whatever the decision they take there will be an unacceptable downside, a negative consequence for somebody. Hence it is difficult to determine what course of action to pursue. Another example, imagine that you are negotiating a large, very lucrative deal for your organization. The problem is that you are aware of a potential downside that had not been properly evaluated using the current company assessment process. On the plus side, closing this deal will guarantee a fat bonus for your entire team. And you know that other teams within your organization have closed similar types of deals with similar risk profiles. Will you close one eye and secure that deal? It means leaving your organization exposed to significant liabilities if the deal goes wrong.

The basis of dilemma is often a contradiction between good and bad. Doing the right thing might lead to bad results and vice versa. Imagine for example that in order to buy a large amount of product from your company, a potential client requires receiving an “under table” commission. If you do not close this deal, you will miss your quarterly revenue target for the third time and most likely get fired. Will you seal that deal? Moral dilemmas arise when the division between what is ethically right and wrong gets blurred.

Dilemmas make managers very stressed as there are no easy ways out and there will often be severe short-term and/or long-term, tangible and intangible costs associated with any decision taken. Dilemmas cause what psychologists call a cognitive dissonance. This is what happens when there is a conflict between values and when somebody acts in a way that is inconsistent with his or her prior belief. This dissonance is a very disturbing and unpleasant experience, usually leading to strong negative emotions such as fear, anger and frustration. The individual experiencing the dissonance will feel the intense need to restore harmony by reducing the dissonance. Managers engaging in unethical and even fraudulent behavior when facing dilemmas will usually be subjected to a strong cognitive dissonance. The factors that help explain why managers will engage in unethical and even fraudulent behavior and how they may be able to reduce the cognitive dissonance and resolve the dilemma can be categorized as follows:

- Ethical Relativism.

- Pressures / Incentives.

- Opportunities / Risks.

Ethical Relativism

People do have principles they believe in but when they practice them, they will also have many exceptions to those principles. For example people may believe in honesty and the importance of always telling the truth. Yet in many cases the same people will not hesitate to lie and by doing so, go against the very principles they profess to follow. We could say that people are morally flexible. It means that practically what is good or bad depends on the context and consequences. To decide, it is necessary to analyze and carefully weigh the options when facing a dilemma. The goal is primarily to avoid negative consequences (especially the one that may affect personally the individual making the decision) by developing creative options.

Hence from that perspective, everything is relative and it is more and more commonly accepted that there are different ways to define truth and exhibit moral behavior. The rationale is that different people may hold different views and follow different principles or interpret those principles differently because of different cultural backgrounds, experiences or personalities. Who is right, who is wrong when everything is relative?

With that in mind it will not be too difficult for managers to rationalize their behavior and reduce the cognitive dissonance even if it violates important values and principles using the following types of arguments:

- “I have been unfairly treated.” The employee has been passed over for a promotion, given a very small bonus despite great results or has just been bullied by the boss. This might lead the employee to feel that taking home company assets is his or her right that he is just restoring the balance of what should have been done.

- “Everybody else is doing it.” Illusion of morality can set in when everybody in the same group is engaging in the unethical or fraudulent behavior. For example, using the corporate credit card for non-business related expenses. The fact that everybody is doing it may give each employee an incorrect sense that it is fine after all.

- “It is not me, it is my Boss.” In some cases, employees will engage in unethical or fraudulent behaviors because their boss told them to do it and they felt they cannot disobey their boss even if the order is unethical, or worse, fraudulent. It is a case of submission to authority, and the employee will rationalize himself as just a tool without free will and responsibility.

- “I'm not stealing, I'm just borrowing the money.” The employee sometimes does have the best of intentions to return the stolen funds. However, there's a snowball effect. The longer the employee gets away with the fraud, the more casual he becomes about the situation. The fraud usually escalates to the point where the employee is unable to pay back the stolen money.

- “I have no choice.” The employee believes he'll lose everything dear to him, including his job, home and family, unless he steals the money or commits the unethical act.

- “I will use it for doing good.” This “the end justifies the means” kind of justification is where the employee can rationalize his or her unethical and even fraudulent behavior because the end result is supposed to be good.

- “If I don't do it, somebody else will.” The inevitability justification: The idea that you cannot go against the flow because then you are missing opportunities or worse you could even get drowned. In 2007, Chuck Prince, former CEO of Citibank Group, to justify his blind pursuit of short-term profit during the subprime bubble, infamously said, “As long as the music is playing, we have to keep on dancing!” (Business Times, 2007).

Pressures / Incentives

It is about the pressure or “need” felt by the individual, which will lead him to commit the fraud. It might be real financial problems coming from personal problems such as unhealthy personal money-sucking addictions/vices (gambling, drugs, alcohol, mistress), or family needs (sick spouse, children), combined with insufficient capital, high debt level and credit difficulties. In most cases, the individual does not want his spouse, child, or parent to know about the problem. He will resort to self-help rather than risk being shamed by admitting that his debt is out of control. It could also come from work-related factors such as being overworked, underpaid and not promoted. There could be the case of too high a level of management pressure to achieve financial results coupled with inappropriate compensation systems that encourage excessive risk taking or a need to cover up someone's poor performance and hide losses. Finally, it could simply be pure greed, such as when a person has a strong desire for material gratifications and will stop at nothing to get what he or she wants. This includes the selfish pursuit of short-term financial gains generated at the expense of other key stakeholders, as Mr. Smith, a former vice president at Goldman Sachs puts it, referring to what he called the toxic culture of his organization in his resignation opinion published in the New York Times (2012, March 14), when he declared that “Not one single minute is spent asking questions about how we can help clients, it's purely about how we can make the most possible money off of them.”

Opportunities / Risks

Regardless of the strength of the pressure or incentive that an individual has, unethical acts can take place only if the opportunity is present. The opportunity for unethical acts or frauds can result from:

- Weak internal controls: Strong internal controls are a business's first line of defense.

- No separation of duties: This occurs when one employee handles many different related tasks. For example, the same employee opens the mail, logs in payments, and prepares and takes the deposit to the bank.

- Indifferent management: Sometimes management doesn't enforce the internal controls set in place.

- Ineffective monitoring of management: This takes place when the company is small and has few managers.

- Collusion among employees can circumvent even the strongest of internal controls.

As a French proverb states, “The opportunity makes the thief” – as soon as there are opportunities you will find people who will take advantage of them. The limitation is that the violator must feel that he/she can take advantage of the situation without getting caught and punished for it.

In conclusion, we need to be aware that when making decisions, pressures and rationalization from conflicts of interests and psychological biases are often underestimated, and will compromise our professional and moral judgment.

Establishing a System and a Culture of Risk Awareness and Ethics

For organizations to manage ethical risk issues effectively it is necessary to stop thinking like mechanics (hard controls) and to start acting like gardeners (soft controls). More and more, management control models emphasize the importance of soft controls and require the development of a pervasive ethical culture to support the control systems and processes in place. It is further recognized that effective compliance is an outcome of ethical behavior. Hence managing ethics and compliance risk holistically is key to fostering and sustaining a strong ethical corporate culture, to support ethical behavior in an organization. As the old adage says, “An organization is only as good as its people.” This is especially true in ethics and legal compliance, where successful management depends as much on how leadership and culture influences employee behavior as on the strength of controls and processes in place. From an understanding of the key factors that explain how unethical behavior can happen in organizations, we can define the key objectives of an effective ethical risk management system as follows:

- Reduce and monitor pressures/incentives factors on employees to engage in unethical acts or even commit fraud.

- Reduce an employee's ability to do the wrong thing and remain undetected for long periods.

- Promote a strong risk aware ethical culture to make rationalization difficult.

Reduce and Monitor Pressures / Incentives Level

It is possible to reduce the pressures created by the stress of work by setting challenging yet realistic performance targets, ensure that pay systems can be perceived as fair by the employees and linking performance reward to real KPIs, i.e. drivers of value not financial results indicators. It also necessary to monitor “red flags” that may indicate that an employee is subjected to personal problems creating financial strain.

Reduce Opportunities, Increase Risks

It is essential to design and implement a solid system of internal management controls combined with effective management oversight of what is going on at every level in the organization. Checks and monitoring employees must be an ongoing process. Finally it is also important to keep people moving through job rotation and promotion so that they cannot build their own “black box” in their department.

Deal with Ethical Relativism and Make Rationalization Difficult

It is important never to underestimate the ability of the human mind to rationalize anything. Thanks to ethical relativism, with little efforts, people can actually rationalize a crime as being a benefit to society. Then the question is how to prevent inappropriate rationalization. The answer can be found in the nurturing of a strong ethical culture supported by adequate control systems. To reiterate, a corporate culture to support good and effective ethical risk management practices must have integrated at least the following values/principles:

- Think in terms of shared value and sustainability.

- Act with integrity and discipline.

- Be responsible and accountable for what they do.

- Be open and transparent about how they do things.

- Share information and knowledge proactively.

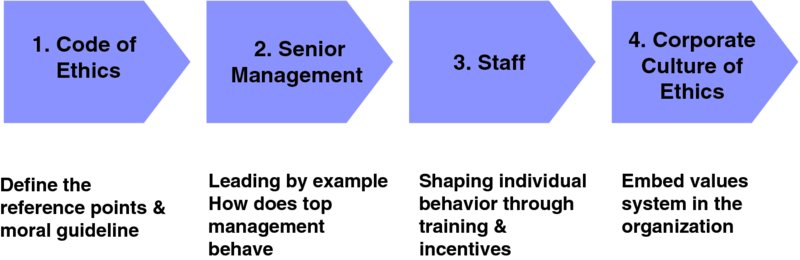

If it has not, unethical behaviors are inevitable and will ultimately lead to corporate failures. To create that kind of positive and ethical workplace environment and culture, it would be helpful the follow the steps highlighted in Figure 4.2.

Figure 4.2 The four steps to ethical behavior.

First, the organization should develop a written code of ethics. The purpose of the code is to deter wrongdoing and to promote honest and ethical conduct that supports the business model of the organization and ensures compliance with applicable governmental laws, rules and regulations. The code of ethics should highlight the key principles and values that are supposed to guide decision making and describe what would constitute unethical or fraudulent behavior. It should also include a process for internal or external reporting of violations of the code to an appropriate person or persons identified in the code. Finally, it should define the accountability for adherence to the code and the sanctions to be imposed on those who breach it.

Second, it is also essential that the board and the senior management team take the lead in establishing the “tone at the top” by “walking the talk” as employees will naturally tend to follow the behavior of their leaders. Hence it is critical for the leaders to lead by example in setting professional standards and corporate values that promote integrity for themselves and other employees throughout the organization.

Third, shaping of employees' behavior can be achieved through the leading example of the senior management team supported by appropriate communication and regular training about the code of conduct and other important ethical issues. It is essential to link performance reward and promotion to ethical behavior so that employees are encouraged to do the right thing for their organization. Similarly organizations must ensure that they are hiring the appropriate employees who display a value system congruent with that of the organization. Finally, there should be zero tolerance for unethical behavior and any violation should be very firmly dealt with whatever the level of the employee concerned. The effort should be maintained over time to, fourth, ensure that the necessary principles and values become embedded in the culture and systems of the organization.

In conclusion:

- Ethics is fundamental to enterprise risk management, and hence ethical culture objectives should be central to an effective ERM program.

- Leading standards and regulations have recognized the centrality of ethics and have explicitly integrated ethics into the elements of effective enterprise risk management.

- Organizations that are serious about implementing ethical principles and practices will not only protect their organization against damaging crises but also create tremendous benefits. A demonstrated corporate culture that supports and provides appropriate norms and incentives for professional and responsible behavior is an essential foundation of good governance, sustainable growth and profitability.

References and Bibliography

How Leeson broke the bank. (1999, June 22). BBC News Online http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/375259.stm

Enron scandal at-a-glance. (2002, August 22). BBC News Online http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/1780075.stm

Marsh & McLennan accused of price fixing, collusion. (2004, October 15). USA Today http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/money/industries/insurance/2004-10-15-spitzer-insurance_x.htm

Musgrove, M. (2010, February 06). BAE Systems pays $450 million to settle bribery scandal charges. The Washington Post http://articles.washingtonpost.com/2010-02-06/business/36873514_1_bae-systems-top-contractor-defense-contractor

Lyall, S. (2007, September 12). Anita Roddick, Body Shop Founder, Dies at 64. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/09/12/world/europe/12roddick.html?_r=0

COSO (2004), Enterprise Risk Management – Integrated Framework, Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission, AICPA, Jersey City, NJ.

ISO 31000, 2009, Guidelines on Risk Management Implementation, International Organization for Standardization.

Power, M. (2004). The Risk Management of Everything: Rethinking the Politics of Uncertainty. UK: Demos.

Citigroup's Chuck Prince wants to keep dancing, and can you really blame him? (2007, July 10). The Business Times http://business.time.com/2007/07/10/citigroups_chuck_prince_wants

Smith, G. (2012, March 14). Why I Am Leaving Goldman Sachs. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/14/opinion/why-i-am-leaving-goldman-sachs.html

4.2 GOVERNANCE, RISK, COMPLIANCE: THE NEW PARADIGM OF RISK MANAGEMENT

Jean-Paul Louisot

Formerly Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, Directeur pédagogique du CARM Institute, Paris, France

No one can deny the depth of the financial and economic crisis the world continues to experience in 2013 after the near collapse of the finance industry in 2008. The combined efforts of twenty heads of state and changes made to financial regulation and the identification of systemic risks created by large institutions may not be adequate to restore the value that was lost. It remains to be seen who will suffer most and, unfortunately, once again the poor populations in emerging countries may be the first human victims, even if Africa did not suffer as badly as was feared at the beginning thanks to its new economic link with the BRICS1 countries.

This economic crisis has profoundly and permanently changed the context in which most organizations operate and strategy, tactics and operations must especially take into account the increased scrutiny of all stakeholders, which has been enhanced through the explosion of social media.

However, at the level of institutions and organizations, the main victim might well prove to be the deregulation that took place at the end of the twentieth century, even in spite of its latest attempt at surviving through the Sarbanes-Oxley Act in the USA and the “tick the box” model named COSO 2, invented by the auditors to offer a quick fix to frightened executives. Obviously, it is still tempting for governments to appease their citizens' fears through the enactment of layers upon layers of regulation to corset the economic actors. Could there be a miracle remedy, a panacea? Most certainly it will prove to be just another temporary fix, unless it starts at the root of the problem – not only the greed of too many, but more deeply the systemic failure of the current “accounting standards” to reconcile the “real” economy with the “virtual” economy. What we experience currently is literally a choking of the former by the latter, covered by a thick foam of non-productive financial assets.

The rating agencies who at best did not see the debacle coming and at worst encouraged it by inappropriately rating some of the so called “toxic assets”, had to reinvent themselves and now operate under a much closer scrutiny by government and industry. It seems that the rating agencies that were at the heart of the trust issue as they gave a “pass”, including triple A rating, to the financial products that failed so abysmally, seem to have discovered ERM as a way to regain the public trust and confidence. To be totally fair, they had started to grasp the importance of a global and integrated approach to risk management and in May 2008, Standard & Poor's announced that it would incorporate an “evaluation of ERM” in its ratings for non-financial companies beginning in late 2008.

However, in times of high volatility, symbols are important and the investment community and the public at large must be reassured and new tightened regulations will probably change their perception of risk, especially as some encompass the interdiction of golden parachutes, a limitation of compensation packages for executives and a consolidation of the real estate market. Access to decent housing for all may be a right, but it is high time that governments realize that it may not mean that all citizens should own their house. But let us not delude ourselves, regulations will not be enough, the cure will require a change of mind, a return to basics and fundamental values; solidarity should remind us that we will either succeed together or sink. And this is true at the level of the organization, at the level of local authorities, the nation and even the world.

Indeed, only governments could curb the excesses of a liberal economy, and the financial crisis has opened a window of opportunity. This, of course is an opportunity, if and only if leaders have the courage to transcend national egoisms to build a “new international order” through which the short-term interests of everyone are aligned with the long-term interest of society. But is this not the true “sustainable development”? It remains to be seen if the agreement signed at the G20 meeting in Washington in 2011 (see box) will be transformed into working documents to offer an international framework for controlling financial activities.

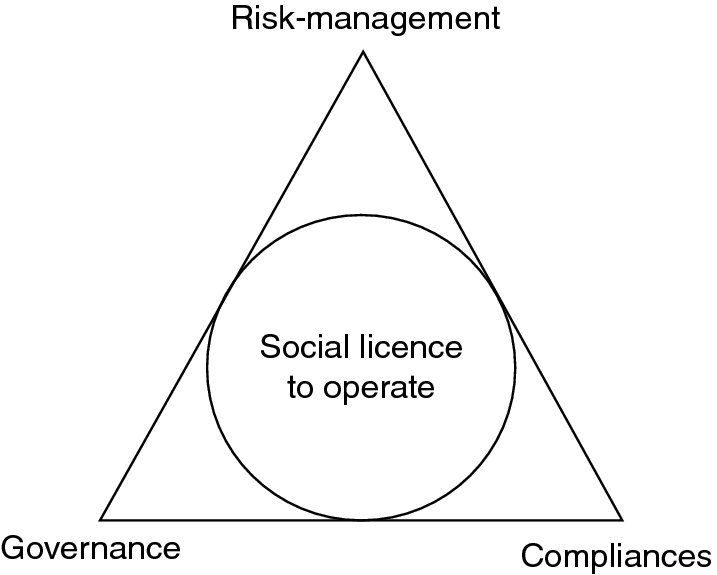

Under these circumstances, the “golden triangle” developed by risk management professionals could prove to be the cornerstone for this reconstruction. In truth, the new risk managers' mantra is GRC, which stands for Governance-Risk-Compliance. In fact, woven in these three words lies what most of the professionals of the world have come to call ERM, from the American acronym for a global and integrated approach to managing risks.

The challenge is the same, whatever the acronym, GRC or ERM, and it could be summarized in this illustration: “In a compliance culture, if you come to a pedestrian traffic light flashing red you would stop and not cross the road. In a risk management culture, you would look at the light, check the road to see if any cars are coming, and if not, you cross it.”2

As a matter of fact, some regulators went one step further in coining the expression “Risk Governance”3 and envisioning risk mitigation and transparency lies at the heart of any governance exercise. However, it remains true that the traditional GRC process promoted by auditors still is a “ticking boxes” exercise.

In contrast, the GRC approach that will be advocated in this article is rooted in the management system of the organization and in complete congruence with the ISO 31000 principles, framework and process. At the heart of the proposed understanding of the GRC triangle is its weaving into the culture, mission, values, and strategy of the organization. In other words, following the GRC model will not in itself ensure ethical behavior. It is essential to understand that compliance is limited and even compromised if it is not ethics driven. Therefore, each point of the triangle contributes to the proper management of any organization: whereas governance ensures that a transparent and objective decision process is in place, compliance is necessary to guarantee the legality of all actions, and risk management provides long-term vision to ensure resiliency and sustainable development.

The triangle developed by some risk management professionals could become the cornerstone for modern risk management reconstruction. In truth, the risk managers' new mantra must be GRC, Governance-Risk-Compliance, and their goal to achieve measureable GRC performance goals. ERM is woven into the central position of these three words, and GRC success requires a global and integrated approach to managing risks.

In November 2007, before the deteriorating financial sector became a crisis, at the RMIA4 conference in Australia, Marianne Robinson5 gave a clear explanation on why the three GRC concepts are fundamentally intertwined:

“Regulatory reform around the world the last 5 years has resulted in enormous changes to public and private sector entities as they attempt to manage the risks associated with overlapping regulation and reform on an unprecedented level.”

The reforms have already driven changes to the concept of corporate governance and the profile of risk management as organizations struggle to accommodate the new legal compliance and corporate governance frameworks imposed by codes of conduct, prudential standards, government and regulators within and outside Australia.

Risk management has been elevated within organizations but often under the guise of compliance and governance. Governance, and legal and regulatory risk, issues have created awareness at director level that was often lacking in the past. Boards are playing a greater role in the monitoring of risk-related issues but there is a price paid for this new level of awareness. Many directors are so concerned with how the business deals with legal risk and their own personal liability that they have become risk adverse. Too many enterprises are still bogged down in time consuming but often ineffective “tick the box” compliance programs. Too many directors and managers are diverted from business decisions that involve innovation, and strategic policy and opportunities.

Another challenge facing both private and public sector organizations is how to manage legal risk and how to implement effective compliance and governance programs without creating a risk adverse environment where the core business comes to a standstill. Many organizations have yet to determine their level of risk appetite while others worry that district attorneys worldwide might be lurking in the background threatening organizations with legal exposures for conduct that was once acceptable but suddenly no longer meets community expectations of what is acceptable.

GRC must become the new mantra for public and private sector entities as they look for an integrated solution and a common enterprise-wide philosophy to underpin three quite different but at the same time similar frameworks (see Figure 4.3), thus they maintain their “social license to operate”. This is why it is essential to consider the enterprise information relationships between governance, compliance and risk management. Senior management must examine how legal risk varies from other forms of risk and look at the relationships between the risk management teams and the compliance teams where training and background are often very different. The open question is whether there is a new type of hybrid risk professional emerging – someone who combines traditional risk expertise with a legal compliance and governance background and what boards need from GRC reporting.

Figure 4.3 The GRC triangle.

The understandable failure of traditional risk management to prevent the global economic meltdown of 2008 makes the comment above even more important for the development of ERM. However, not all practitioners share that vision on GRC and Michael Moody wrote:

“A recent organizational trend has been to integrate risk management with compliance and governance. This fusion is frequently called ‘governance, risk, and compliance (GRC)’, but it often leads to companies relying too heavily on the ‘checklist mentality’.6

This fusion has led boards to raise objections related to compliance-related challenges. Many directors are worried that the executives in their organizations are devoting too many resources to compliance issues and not enough efforts to competitive business initiatives. Some analysts have implied that a GRC approach that includes risk management in a wider framework is not sustainable over the long term. Therefore, the question remains open to envision risk management as an exercise separate from compliance and oversight.

Although the potential pitfall stressed by Michael Moody and his followers cannot be underestimated, there remain major drivers for an integrated approach to the three sides of the GRC triangle and they explain while this trend seems to be prevailing today:

1 The Intrinsic Relationship Between Governance and Risk

An organization's exposure space comprises all the types of risks; a number of them may potentially affect the achievement of its objectives. Some of those risks stem directly from the governance. The governance philosophy of the company (as embodied in the organization's governance framework, policies, practices and the implementation of these policies) may not support the organization in the pursuit of its goals.

But conversely, the governance framework of an organization is also a risk management tool adopted by the board, as it is clearly the board's responsibility if they agree on its empowerment by the stakeholders.

2 The Elements of a Typical Governance Framework

There are many governance frameworks that can apply to an organization's compliance mandates. Each organization must develop its own hybrid framework to fit its purposes. The governance framework will reflect regulatory oversight and market performance expectations. An effective governance model should be based on the premise that corporate governance:

- Is not just about regulation and legislation, it is about doing what is right for the stakeholders.

- Is broader than boards and committees; it extends throughout the organization, and includes internal controls and compliance functions such as risk management and internal audit and external audit.

- Requires transparency of disclosure, effective communication, and proper measurement and accountability as essential elements for good governance.

The foundation of an effective governance model is the corporate structure that includes the owners of the business in the form of the shareholders, who appoint a number of trustees, in the form of a board of directors, to oversee their interests in the business and who in turn hire a chief executive to develop business strategies, employ resources, build and operate processes, generate profits, and increase the value for the shareholders.

3 The Impact of Culture on Governance and Risk Management; and the New Ethics Frontier

In the past few years, organizations have focused much energy on developing robust governance and risk management infrastructure. Despite this focus on getting the cultural design right, many organizations still find that the governance and risk management balance is not working properly. In a recent survey of the world's leading global mining companies,7 the majority of respondents nominated the embedding of risk management into their culture as the key future challenge for their organizations.

So it would appear that for many organizations struggling with embedding governance and risk management in their culture, the answer may lie in aligning enterprise risk management goals and assessment practices at the top of their organization.

Defining the enterprise risk management culture of an organization rests on developing the necessary competencies of all staff and should provide insight on why things are the way they are. For example, is it acceptable to circumvent a particular policy or control without clear accountability for decision making? For the “risk management culture” defining the tone at the top is vital as top management can influence that culture through measureable policies linked to management reporting practices. Culture may be an intangible but we can introduce tangible measures to impact it, like recruitment processes, whistle blowers provisions, etc. This is what is required to influence behavior and confirm governance alignment with risk management performance goals. However, it is important to remember that truly changing culture is usually a slow process; it is not typically a quick fix.

Among the spheres of activity defined in the Cindynics8 approach (see Brief overview of the Cindynics) combining several of the five dimensions of the description of an individual perception of risks, the three-dimensional space regrouping objectives, norms and values is the sphere of ethics “in action”. If one is to judge only by the volume of academic publications, professional articles and conferences, ethics plays a growing role in development on organizations' management at any level, private and public entities, NGOs and healthcare institutions, as well as governments. Managers, as well as elected officials, cannot limit themselves to an “efficient stewardship of the means”, but need to question the ends; in other words they must revisit the goals and missions, redefine the norms and analyze the values that guide their leadership. This emergence of ethics as a management topic has become embedded in the culture of many organizations but there is still a long way to go. Could it be that reviving ethics was made necessary when the free economy model lost its counter-model, communism, and thus lost its counterbalance and mirror?9

Whatever the origin of this trend, it becomes clearer every day that standards and best practices cannot be limited to the pursuit of profit and the creation of value only for the shareholders. The allocation of colossal heaps of resources, often more than the GDP of “middle-sized nations”, by private economic operators puts on the shoulders of those making these decisions the responsibility to question the ends which these means are serving. This is precisely why not only the executives of global companies, but also the leaders of local entities, the mayors, the county chairs, the state officials as well as healthcare managers must revise their objectives and missions, redefine their norms and establish their values, taking into account all the components of the society and the expectations and fears of all their stakeholders to ensure that there is value creation for all.

Under this new paradigm every leader must rethink his/her strategy in the context of the society's mission to its members, now and tomorrow. Ensuring that all behave “ethically” supposes that values are clearly defined, obeyed by all and that the “ethical frontier” is understood by all, and never to be transgressed without consequences.

If all issues were black or white, choosing the “right” solution would be easy. However, most ethical issues are grey and the level of grey may depend on the set of values for any given individual or any given organization. Therefore, whereas there is a minefield beyond the “ethical boundary” for everyone, the boundary differs from one entity to another, one period to the next. The ethical boundary, or set of values, is an integral part of what is often referred to as “corporate culture”. It results from the “living and growing together”, and the role of top management is essential in attracting and retaining employees that will fit into the culture and feel the bond to work together: the “affectio societatis”.

As a matter of fact, as the recent developments on the financial institutions illustrate too clearly, the question that each member of staff must ponder with each decision is not so much “Could I?” that is the compliance question, but rather “Should I?” that is, is it in accordance with my own principles and values, with the values of my organization? Put in blunt terms: If the media published the consequences of my decision, if my children knew it, my spouse, my friends …could I still look at myself in a mirror without shame, even with pride?

To summarize, the ethics dilemma could be summarized in a simple question that the G20 leaders should ask themselves: “Is it not time simply to refocus the economic system on the essential, make it its core mission to ensure humanity's well-being, rather than the accumulation of wealth?”

Beyond compliance, it is ethics that is at the core of reputation creation, with risk management and governance, i.e. the patient building of trust in all stakeholders, the strategic ingredient of resilience in the time of trials and ruptures; trust is undoubtedly the ultimate survival kit in a society so geared towards image, and reputation.

Too often, good intentions do not transform into good actions. The code emanating from the Orange Book issued by Her Majesty's Treasury stipulates that local authorities in the UK must conform to six principles of good governance that could serve as a model precisely at the time when the world leaders are searching for a new fuel to jumpstart the world economy engine:

- The efforts and means of the organizations must be allocated solely to the fulfilment of users' and citizens' needs.

- Each member of staff must work efficiently within clearly defined missions and roles.

- The good governance values defined by the organization must be publicly disclosed and adhered to by all involved in the organization's operations.

- All decisions must be informed and transparent, taking into account all the risks involved.

- Leaders (appointed as well as elected) must be trained to possess the competencies and skills needed for the efficient performance of their missions.

- Communication and consultation must be established with all stakeholders, and all must be accountable for the results obtained.

These principles are rooted in a key element, trust – the trust essential in any economic system short of bartering. Will the leaders of all countries, developed, the BRIC10 countries, or BRICS if South Africa is included, and emerging countries finally find the courage to develop a vision, beyond egoistic interests, to redress or rebuild the global economic structure on firm principles? Time is of the essence. And risk management professionals should be called to play a key role; however, the GRC triangle, the golden triangle for the profession, seems to have become a Bermuda triangle for industry if risk managers hesitate too long to deploy it.