“Caroline says, as she gets up from the floor, you can hit me all you want, but I don’t love you anymore”

—Lou Reed

As we mentioned before, the eurozone has some interesting similarities with Japan, and many differences, of course. The similarities are an aging population and a corporate structure that resembles a lot the Zaibatsu– Government ties.

That’s probably where the similarities end. But those two factors matter, as we will see later.

There is a third factor that reduces any expected positive impact of monetary policies, and that we mentioned before: overcapacity. See Figure 6.1.

Low capacity utilization is often regarded by mainstream economists as a problem of demand that needs to be “stimulated.” However, paying closer attention to the data shows the opposite.

Figure 6.1 Capacity utilization in the EU has not improved despite years of industrial plans and credit boom

Source: Eurostat, Trading Economics.

Stimulating demand is precisely what the EU has been doing since the project and creation of the common currency.

Credit soared, with loans to the private sector rising 225 percent between 1999 and 2008. Public investment to GDP averaged 3 percent every year during the period. In the same period, money supply more than doubled while government-spend-to-GDP never fell below 44 percent. Household debt rose from 45 percent of GDP to 63 percent. A problem of demand stimulus? Really?

A credit boom fueled by illusions of a high-growth union and low interest rates that the central bank almost halved while doubling its balance sheet.

The eurozone crisis was exactly like all the ones we had seen before, a massive credit bubble that exploded.

And when the bubble burst, everyone blamed anything except ... themselves.

Speculators were blamed for stocks falling and bond yields rising. No one seemed to worry about them when markets soared.

Governments and politicians blamed private debt.

Households blamed banks.

No one seemed to ask, “How will we repay this ever-rising debt if growth stops?”

And, finally, some countries blamed the currency. If they had not been in the euro they would have devalued and everything would be fine. Except none of those countries asked themselves if the level of spending, investment, and development achieved within the common currency would have been feasible with their domestic currencies. It seemed every-one liked being attached to Germany for the boom, but not for the sobering bust.

Trichet Was Right

Incredibly enough, in Europe many blamed the president of the ECB, Jean-Claude Trichet, for raising rates in 2011 when the credit excess was becoming not only evident, but dangerous.

The media and mainstream economists considered raising rates at that time a mistake, as it happened in the middle of a debt crisis. But raising rates to ... 1.5 percent? That was the “big mistake”? Seriously? See Figure 6.2.

Figure 6.2 European central bank benchmark rate

Source: ECB.

Interest rates were at 4.75 percent in 2000; they were lowered to 1 percent, raising rates twice a quarter of a point to a mere 1.5 percent after a massive credit boom and excess capacity, and after governments had increased debt in some cases by more than 100 percent.

Yes, there was a crisis. The decision to increase rates came at the same time as the eurozone was preparing bailouts for Greece and Portugal. But rates had been cut to historical lows and if anyone believed that 50 basis points would make a difference, they were simply fooling themselves.

Cheap Money Is Not the Answer

The eurozone crisis was not going to be solved with much lower rates.

Let us remember that, when the U.S. subprime crisis erupted, the UK financial system entered turmoil and the ripple effects were seen all over a world that had grown used to massive credit growth and low rates, the EU prided itself on being somewhat isolated from the whole financial tsunami.

Spanish banks, for example, were praised for having better regulation and thus escaping the financial crisis.1

To combat what the media called “a financial crisis that originated in the United States” and had nothing to do with the eurozone, interest rates were dropped massively and the balance sheet of the ECB increased by €1 trillion, supporting sovereign bonds.

Additionally, the EU embarked on a disastrous “stimulus plan” that further increased the risks without any discernible growth. On November 26, 2008, the “plan for employment and growth” was launched, an ambitious project to “relaunch the economy” and create “millions” of jobs from public investment.2

To combat the crisis, a stimulus of 1.5 percent of GDP, more than €200 billion, was implemented—unproductive investment in white elephants and “strategic” sectors as had been done during a decade of industrial plans. Stimulate demand. White elephants had to be replaced with ... white elephants.

-

Spain spent €90 billion on infrastructure and civil works projects with a negative impact on both GDP and employment, as well as a debt shock.

-

The EU set out to spend €200 billion and on the way destroyed 4.5 million jobs, increasing the deficit to 4.1 percent of GDP.

-

The only countries that reduced taxes as stimulus were the Netherlands and the UK. Not surprisingly, they were the ones that got out of recession earlier.

This stimulus plan is still felt throughout Europe. Empty motorways next to each other, useless airports, deserted “technology centers,” enormous empty buildings, industrial areas without any business activity, and so forth.

Industrial overcapacity soared, as did debt, but not growth or revenues.

The eurozone sovereign crisis continued to explode because imbalances that had been widening for more than a decade were starting to become evident. The eurozone was built under the premise that public debt had no risk,3 and woke up to the harsh reality that risk is not decided by a committee of politicians. Credit Default Swaps (CDS), the instruments that cover the risk of default on bonds, exploded in price all over the eurozone as the massive bubble of corporate, banking, and sovereign debt pricked throughout the countries. On top of the evident risks, the concerns of a euro breakup—fueled by some reckless politicians and many unrealistic economists—made alarms ring all over Europe.

Figure 6.3 Total banking assets as a percentage of GDP

Source: Merrill Lynch; central banks.

European banks, which were supposed to be extremely regulated and adequately capitalized, showed that it was all a mirage and the amount of real nonperforming loans became more evident.4 Suddenly, the propaganda that it was all a U.S. problem of nonregulation presented a harsher reality.

Total banking assets in the eurozone exceeded 320 percent of GDP. See Figure 6.3. At the peak of the crisis, in the United States, these were 80 percent.

Furthermore, banks that were loaded with sovereign debt from their own country and from others, found it increasingly difficult to lend and borrow as well. The insurance to cover possible defaults (CDS) continued to rise as financial entities tried on one hand to reduce exposure to government bonds and at the same time maintain core capital.

As I mentioned before, risk appears suddenly, and abruptly, due to accumulation of exposure to an asset that seems very safe. Public debt, government infrastructure projects, and housing.

Banks were unable to contain the bloodbath in their portfolio of assets; stocks fell, while governments that had been increasing debt by deficit spending between 2008 and 2011 because they had fiscal space, found that their refinancing costs soared. The link of external risks can be seen in Figure 6.4.

As the banks lost capital with the collapse of the value of some of their assets, sovereign bonds, loans that were increasingly unlikely to be repaid by governments, municipalities (from the “stimulus”), corporates, and families, the risk of a bank run led to widespread bailouts to avoid a collapse of the deposits of clients and a financial collapse. See Figure 6.5.

Figure 6.4 Exposure to Eurozone sovereign debt, 2011

Source: BIS.

Figure 6.5 Europe bailout costs, 2016

Source: Elva Bova, IMF.

Many believed that devaluing would be the solution to years of excess, forgetting the devastating results of competitive devaluations of the decades before the common currency, which we mentioned in previous chapters.

The ECB’s Unjust Reputation

Media and politicians always blamed the ECB for not doing as much as the Federal Reserve because, historically, the EU had denied its imbalances and risks by covering them with more credit and the layer of monetary policy.

However, by 2013, at $3.5 trillion, the Fed’s balance sheet was very similar to that of the ECB. The ECB had increased its balance sheet by $1.5 trillion in four years, including €218 billion in sovereign bond purchases.

In 2013 BNP Paribas published a very revealing report titled Bigger than QE showing how the ECB’s policy had flooded the system with credit. The main beneficiaries of this policy were Italy and Spain, two of the countries that complained the most about ECB “inaction.”

Money supply (M3) reached a maximum of €9.7 trillion in January 2013 compared with an average of €0.33 trillion from 1980 to 2012, per data from the ECB. Nearly all of this increase in money supply went to one item: “Credit to General Government.”

Surprisingly, the ECB had been as aggressive as the Federal Reserve, just silent. And that was the problem for market participants: the lack of big announcements that would drive markets soaring again.

All that liquidity had been absorbed between hypertrophied governments and banks buying sovereign debt, but little went to businesses and families, as deleverage continued.

The transmission mechanism problem that prevented liquidity from reaching to the real economy came partially from an unintended perverse incentive in regulation, as sovereign debt was accounted as no-risk, while lending to corporates and families was penalized with higher capital requirements. Neither Germany nor the Bundesbank, which had two-thirds of its balance sheet exposed to the ECB, were to blame. It is hard to believe they had any interest in seeing things get worse.

But the ECB, Germany, or the Bundesbank could not just sit down and maintain unsustainable economies without reforms.

There are perverse incentives in providing endless liquidity to countries that play the game of reaching the limit without reforms, wait to be systemic, get a bailout, and continue without changing bloated state structures, using the checkbook of others.

The EU was built on the premise of solidarity. But solidarity is one thing; donation is another. Especially when debt in northern countries was not low, with debt-to-GDP ratio of 80 percent and their own banking problems, doubling the bet on the periphery spending would have been suicidal after seeing the disastrous results of the previous “stimulus” of 2007 to 2011.

Greece. The Example of What Not to Do

The Greek drama unfolded and put pressure on European markets all throughout the years 2008 to 2016.

The real drama is that none of the measures announced by different parties solved Greece’s real issues.

No, it was not the euro or austerity plans that crippled the Greek economy, neither was it the cost or maturity of debt. Greece pays less than 2.6 percent of GDP in interest and has 16.5 years of average maturity in its bonds.5 In fact, Greece already enjoys much better debt terms than any sovereign restructuring seen in recent history.

Greece’s problem is not one of solidarity either. Greece received the equivalent of 214 percent of its GDP in aid from the eurozone, ten times more, relative to GDP, than Germany did after the Second World War.6

Greece’s challenge is and has always been one of competitiveness and bureaucratic impediments to creating businesses and jobs.

Greece ranks 81 in the Global Competitiveness Index 2015, much higher than Spain (35), Portugal (36), or Italy (49). In fact, it has the levels of competitiveness of Algeria or Iran, not of an OECD country. On top of that, Greece has one of the worst fiscal systems and limits job creation with a combination of high bureaucracy and aggressive taxation on SMEs. Greece ranks among the poorest countries of the OECD in ease of doing business7 at 61, well below Spain, Italy, or Portugal.

Greece’s average annual deficit in the decade before it entered the euro was already higher than 6 percent, and in the period, it still grew significantly below the average of the EU countries and peripheral Europe.

Between 1976 and 2012 the number of civil servants multiplied by three while the private-sector workforce grew just 25 percent. This, added to more than 70 loss-making public companies and a government-spend-to-GDP figure that has averaged 49 percent since 2004, is the real Greek drama, and one that will not be solved easily.

The Greek crisis will not finish by increasing taxes to businesses, or by making small adjustments to a pension system that remains outdated and miles away from those of other European countries. A 12 percent “one-off” tax on companies generating profits of more than €500,000 crippled job creation and incentivized tax fraud.

The inefficacy of subsequent Greek governments and Troika proposals is that they never tackle competitiveness and help job creation, they simply dig the hole deeper by raising taxes and allowing wasteful spend to go on.

From a market perspective the risk was undeniably contained with the ECB’s support, but not inexistent. Less than 15 percent of Greek debt in 2016 was in the hands of private investors. Most of the country’s debt was held by the IMF, the ECB, and EU countries. The most impacted by a Greek default would be Germany, which held bonds of the Hellenic Republic equivalent to 2.4 percent of its GDP, and Spain, at 2.8 percent of GDP.

The main risk for the eurozone comes from a prolonged period of no solutions. Not Greece leaving the eurozone, but a “Greek Drag,” dragging on for months with half-baked attempts to sort the liquidity crisis.

Spain. An Example of Reforms That Work

On the other hand, the Spanish recovery from the worst crisis in decades was impressive. In five years, from 2011 to 2016, Spain could recover more than half of the jobs lost during a crisis that was initially denied, and deepened afterward, by misguided policies.

Since then, Spain slashed its fiscal deficit by half and cut a dangerously high trade deficit to almost a balance. Exports rose to 33 percent of GDP despite its largest trade partners being stagnant or in recession in the period.

Support from the ECB, low interest rates, and cheap oil prices helped the economy, but those factors have also helped European neighbors like Italy, Portugal, or Greece, with similar sensitivities to energy and interest rates—and none showed the growth and recovery seen in Spain.

The reason for the difference in performance of Spain relative to other neighboring countries was a very ambitious set of structural reforms that were praised as an example for others by Mario Draghi: a financial reform that helped change the perception of risk of the Spanish financial system, a labor market reform that turned around a seemingly unstoppable trend of unemployment and recovered jobs and salaries, a moderation in government spending without reducing social expenditures, and a fiscal reform in 2015 that reduced corporate and income taxes.

The remaining imbalances of the Spanish economy—an elevated public debt, deficit that is still large, and unemployment—will not be solved with monetary policies, but by learning from the economies that emerged from the crisis stronger, such as the UK, Ireland, and Germany, and with higher job creation. The measures that would strengthen the economy further should include supply-side reforms, attracting foreign investment, putting more money in companies and in citizens’ pockets, and improving public sector efficiency while retaining a strong but sustainable welfare system.

ECB Launches QE

On November 1, 2011, Mario Draghi began his term as president of the ECB.

His position as president has always been supportive of expansionary policies but warning of risks and reminding of the need to conduct structural reforms and cut taxes.

Since 2015, the ECB has carried out a massive monetary stimulus—asset purchases of more than €60 million a month and zero interest rates—with more than disappointing results. However, like Trichet before him, Draghi cannot be criticized for his work, which has been exemplary in avoiding risks, calming the periods of panic, and reminding politicians and media with fastidious insistence that “monetary policy does not work without reforms.”

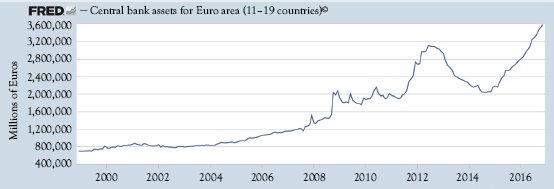

The ECB stimulus plan has led to the balance sheet of the central bank to surpass that of the Federal Reserve, as shown in Figure 6.6.

Before that, the ECB had carried out the most logical policy of all OECD central banks. It had taken advantage of a period of excess liquidity to reduce its balance sheet, which had inflated disproportionately between 2005 and 2011, while maintaining the total credit to the system. The surplus liquidity showed that the problem was not of stimuli but of excess of indebtedness and overcapacity.

Mario Draghi has been prudent enough to warn of the mistakes of governments that rely only on monetary policy while at the same time putting the necessary tools available so that no one accused him of not supporting the economy.

Figure 6.6 ECB balance sheet, all assets (2016, FRED)

The ECB started buying up €60 billion of assets per month, in many cases reaching more than 100 percent of demand for some bond issuances; it then increased the program to €80 billion per month. Excess liquidity increased from €75 billion to more than €1 trillion.

No one can accuse Draghi of not applying the extraordinary policies that mainstream economists and media demanded. He showed month after month that growth problems are not solved with more liquidly, that inflation is not created by a committee’s decision, and that the central bank does not print growth.

By the end of 2016, the EU showed that, since 2011, it needed two additional units of debt to create a unit of GDP.

Draghi’s challenge was to show that the monetary policy transfer mechanism worked and that the central bank was not to blame for poor credit and GDP growth. The improvement in the spreads between the cost of debt for states and companies, especially SMEs, was unquestionable, yet credit flow was still subdued. Because there was no real demand.

In addition, the crowding-out effect that made governments absorb almost all available credit between 2011 and 2013 moderated, with credit growth to private nonfinancial sectors growing close to 3 percent in Draghi’s mandate.

The Perverse Incentives

But Draghi’s biggest challenge will be how to get out of an expansive policy.

It is easy to start and buy billions of bonds, but if the Federal Reserve, with the dollar as the global reserve currency, found it hard to raise rates from 0 to 0.25 percent, imagine how complicated it is going to be to stop an expansive policy in a Europe where governments refuse to recognize the problem of excess spending and poor growth. Even worse, in a Europe where three out of four political parties think that the solution to a problem of excessive debt and spending is to spend more, the work of the ECB is going to be very hard.

That is why Mario Draghi always repeated the same words: “the ECB’s policy will remain accommodative as long as necessary, but it cannot replace government inaction or undercapitalized banks.” And he was right. Monetary policy is not a substitute for inefficiencies.

The construction of the EU cannot come from the same mistakes of the past, because the domino effect of systemic risk makes Europe weaker and more indebted.

Despite the messages from the ECB president, perverse incentives remain. Banks’ refinancing endlessly their more troubled loans due to low rates and high liquidity means that the figure of nonperforming loans does not fall, leading to new banking crises seen in Portugal and Italy, after Cyprus and Greece.

Governments getting used to extremely favorable, but artificial, conditions means that politicians demand more expenditure, and deficits, although falling, remain elevated, with refinancing needs exceeding €1 trillion per annum for 2017 and 2018.8

Countries that have not seen clear improvements in their financial situation, and have increased their debt, are otherwise issuing debt at the lowest rates in the historical series. This policy of ignoring risk and increasing imbalances when rates are low and credit is available leads to chronic sovereign debt crises.9

Countries must be aware of the risk of a shock as the central bank is purchasing between 50 and 70 percent of all the debt that they are issuing, and it is more than unclear if any private marginal buyer would step in to purchase debt at such low rates if the central bank finishes its easing program.

Full Monetization of the Debt Is Suicidal

Debt monetization has a domino effect. It spurs foreign investors to sell domestic currencies, as money supply exceeds real GDP by many multiples, to cover ever-growing public-sector expenses, leading to a disproportionate burst in inflation.

Out-of-control inflation harms the ability of businesses to sell their goods and services because margins fall and they cannot increase prices at the pace of inflation, because citizens’ real salaries do not grow in line with said inflation and purchasing power collapses.

Inputs in the economy become more expensive and, in many cases, sellers will not accept the local currency because of its volatility and constant devaluation, leading to a loss of foreign reserves from the central bank, which, in turn, leads to a larger devaluation as the new currency issued is unable to cover the needs of the country in real terms.

There is a very fine line between the central bank’s credibility and the use of a currency as a credible means of transaction. The euro is used in less than 20 percent of global transactions, and its position as a reserve currency, its value to the world, is not decided by a committee.

Those who defend full monetization know that it is devastating for families and the private sector, but—like the socialist monetarists of Argentina and Venezuela—are willing to accept those damages to the economy because, in exchange, the power of the public sector soars, albeit in a much smaller and less productive economy.

That is why the central banks that conduct expansionary policies and at the same time remain solid economies are always keeping in mind the importance of a secondary market and put inflow of capital into their economies as a key driver.

A central bank that issues a currency that no one accepts as means of payment is as effective as a business that creates a product that is not demanded. A recipe for bankruptcy.

Challenges Ahead

The most dangerous policy is to increase deficits in a low-rate environment. Neither the expected growth is generated nor is one prepared for future rate increases. And the problem is that the mismatch in liabilities and revenues is covered with either higher taxes or a financial crisis, or with an inflation that destroys the purchasing power of citizens, and alongside, the potential for growth.

When we look at debt risk we must analyze two variables. Stock and flow. If confidence is maintained in our solvency and structural improvements are introduced that make the economy more solid and competitive, the stock—the total amount of debt issued—is not at risk; if prices of goods and services rise due to better consumption and productivity, neither is at risk. If markets question the ability to repay the debt maturities, and prices rise only due to monetary intervention, creating stagflation, the risk in a sell-off in the stock of debt is important.

But the flow of new issuances is very important. EU countries have done a great job improving the average life of their debt while reducing their net financing needs, but it is not enough given the large imbalances. If countries once again accelerate annual financing needs by increasing deficits, they put at risk not only their capacity for financing but also the cost—even if they have the ECB’s support. A clear case is Portugal, which has the same support from the ECB as other countries, and its risk premium is over three times higher than that of Spain.10

Countries need to pay attention to the risk of accumulation of debt. Entering a deficit spiral would generate many more cuts when the rates rise. If we meet in 2017, we will be far from that risk. If we go back to the policies of 2010, we launch into a crisis.

Many risks persist from an aggressive monetary policy, but the ECB must be praised at least for constantly monitoring the risk of bubbles and repeating the need for structural reforms to boost growth.

The ECB shows how a central bank can learn from its mistakes and help in unforeseen risk circumstances. But it also needs to advance rapidly in improving credibility through more conservative and realistic forecasting while paying less attention to financial markets.

1 Spanish Boom and Bust and Macroprudential policy. ángel Estrada and Jesús Saurina, Banco de España (BdE), 2016.

2 http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/articles/eu_economic_situation/article13502_en.htm

3 Explicitly men.

4 More than 200 billion euro in 2010–12, ECB figures.

5 2016.

6 Germany, Greece, and the Marshall Plan, a riposte, Jun 21st 2012, Hans Werner Sinn | IFO Institute.

7 Doing Business, World Bank, 2015.

8 Total refinancing needs, not net financial requirements. Source Bloomberg.

9 Chronic Sovereign Debt Crises in the Eurozone, 2010–2012, TJ. Kehoe, C. Arellano, J. C. Conesa, Federal Reserve of Minneapolis, May 29, 2012.

10 Risk Premium is the differential between the German bond yield, considered the lowest risk, and the bond yield of the country.