“You never give me your money, you only give me your funny paper”

—Lennon/McCartney

The great Nobel laureate Simon Kuznets once said: “There are four kinds of countries in the world: developed countries, undeveloped countries, Japan and Argentina.” Both Japan and Argentina share only one thing in common. The two countries commit the same mistakes repeatedly, and said mistakes are always in monetary policy.

There are numerous factors that differentiate both economies, of course. I would not dare to compare them in productivity, population, technology, or competitiveness. Argentina’s massive monetary imbalances erupt in monster inflation rates and devastating banking crises. Japan’s slow burn comes from ballooning debt and secular stagnation.

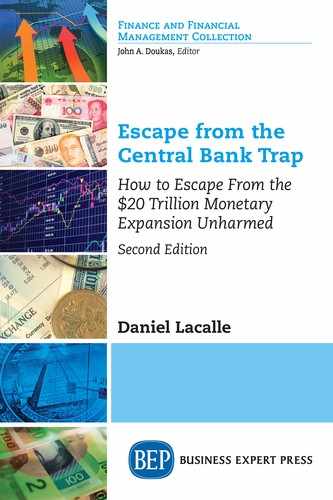

More than 20 years of zero interest rates. See Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1 Japan: interest rates vs. government debt to GDP

Source: BoJ.

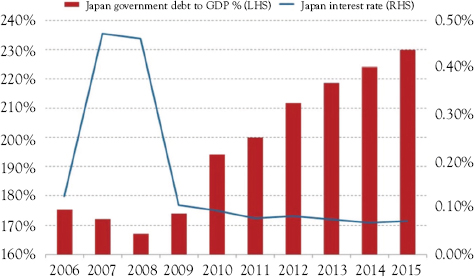

Figure 5.2 Abenomics is nothing new. Previous stimulus also failed

Source: Fulcrum, FT.

“Those who believe in Abenomics are suffering from amnesia. This is nothing new.”1 As can be seen in Figure 5.2.

Abenomics was named after prime minister Shinzō Abe. After nearly two decades of economic stagnation, the plan would launch Japan into a new era, and it was presented in December 2012 with big headlines of an ambitious and innovative policy that would change the country’s fortunes. Growth, jobs, and escape from deflation.

The plan was focused on three arrows,2 using the Japanese saying that one or two arrows can be easily broken with hands but breaking three is almost impossible.

The first arrow was an even looser monetary policy from the BoJ—nothing new. After nearly two decades and six stimulus plans, the central bank would purchase assets at a pace not seen in decades. By 2017 the central bank balance sheet was expected to exceed 90 percent of GDP.

The second arrow was nothing new either: a fiscal boost from increased spending on public works.

“From Meccano to Legoland, here they come with a brick in their hand, men with heads filled up with sand. It’s build.” The Housemartins

Yes, Japan spent between 1991 and 2008 a whopping $6.3 trillion in infrastructure projects to “boost growth,” with an inexistent impact on economic output—the country stagnated for two decades—or on real wages. Japan’s economy did not become more dynamic, but much less, after the bonanza in infrastructure.3

The third arrow was more ambitious: A sweeping structural reform to make the economy more productive and competitive, attacking “special interests”—corruption—and incentivizing high productivity, lower bureaucracy, and dynamism. Guess what? The third arrow was forgotten.

Shinzō Abe outlined measures such as setting up special economic zones but failed to address reforms surrounding the labor market and corporate taxes. No real reform of a bloated state, of vested interest and cronyism problems, rigid labor laws, poor margins, and inefficiencies of the system.

Some commentators mentioned that anyone expecting a broad overhaul of Japan’s economy that would remove barriers to competition would likely be disappointed, and they were right. By 2016, policies seemed to be focused more in perpetuating the status quo and betting any improvements on money printing.

Jesper Koll, head of Japanese equity research at JPMorgan Chase in Tokyo stated: “You are in a country that is obsessed with creating a Japanese-style capitalism rather than market fundamentalist, Anglo-American-style capitalism. It’s still Japan.”4

So, as the reader can imagine, growth did not happen, inflation did not improve, and real wages continued to be at decade-lows while debt rose to the highest level in the OECD.

It is not just public debt. Zero interest rate policies have also made private debt soar. At the end of 2016, Japan’s total debt stood above 450 percent of GDP.5

But the reader might think, how did they get there?

Japan’s All-Too-Familiar Bubble

In 1980, Japan’s budget was just 45 trillion yen. Most of it was public works, government transfers, and interest payments.

Japan entered a massive boom led by construction. The stock and property markets soared, and with them the growth illusion and extraordinary tax revenues created by the bubble. Not only did Japan become richer, but its companies entered an enormous process of international expansion. It seemed like Japan would take over the world. See Figure 5.3.

This sounds familiar to any U.S., Spanish, Swedish, or now Chinese citizen ... the illusion of magic revenues from housing booms. With the bubble, spending also increased, and borrowing expanded.

Then, bust ... Japan’s real estate bubble exploded, and the country, to reactivate the economy, did exactly what the reader has guessed—it created a massive infrastructure plan to boost growth. Expenses continued to soar, driven also by more welfare costs from aging population and accumulated interest payments from the debt incurred during the “this time it’s different” boom.

Obviously, that growth did not happen, but the debt stayed. After six stimulus plans and two lost decades of deflation and almost no growth, the country presented a new plan6 that was just the same, but bigger.

Japan’s crisis was simply the pricking of a bubble in very slow motion and the perverse negative effects of decades of stimulating low-productivity sectors. This policy bloated the economy and killed its dynamism, at the public and the corporate level.

Figure 5.3 Comparing the U.S. and Japan housing bubbles

Source: doctorhousingbubble.com

Why Japan Is Unlikely to Change

Japanese citizens do not suffer from amnesia. The population is aware of the unlikely effect of all these measures announced as “new.” And they save, a lot.

Fifty-six percent of the total wealth of Japanese citizens is accumulated in deposits and currency.7 The government feels the urge to stick its hand in their pocket ... devaluing.

But the Japanese, like the Europeans, do not spend more. The big problem is that the velocity of money—which reflects economic activity—continues to fall despite aggressive liquidity. The lack of consumer confidence does not dissipate by manipulating monetary variables because most fears come from the fear of further increase in taxes and cost of living.

After years of stimulus, Japan published its 2017 budget on its way to another year of pauper growth and high debt.

Japan should matter to all of us. Because it is an example of what countries in the rest of the world should not do after two decades of stagnation and repeating stimulus after stimulus.

The Economist places Japan again among the 20 economies with lowest growth for 2017 and estimates 0.5 percent GDP growth per year between 2017 and 2021.

The country’s budget is yet another example of Abenomics as a total failure. The plan launched by Shinzō Abe to boost growth and fight deflation delivered, as expected, the poorest results imaginable.

The first problem is the enormous debt. Tax revenues cover about 60 percent of the expenses in the budget. The rest is financed by issuing more debt, which already exceeds 229 percent of GDP.8

Neo-Keynesians who repeat that we should not care about accumulating debt “because interest rates are low” ignore that almost 20 percent of the budget goes to interest payments even though Japan’s cost of debt is very low (0.10 percent for a 10-year bond).

However, it is dangerous to ignore that the BoJ will “swallow” the vast majority of those bonds issued.

The closest thing to a Ponzi scheme?9

By the end of 2016 the central bank of Japan accumulated more than 35 percent of the bonds issued by the government as well as owned the largest share of ETFs10 in the country.

The central bank of Japan was on the path to become the largest share-holder of 55 companies in the Nikkei by end of 2017 and is already one of the top five shareholders in 81 of them.11 This is as close to a pyramid scheme as one can imagine.

Many problems affect the Japanese economy, but the largest one is that of a rapidly aging population, which is not solved by printing money. More than 40 percent of the budget goes to pensions and health care.

But above all, monetary policy and government stimulus do not guarantee pensions, which were cut again in FY 2017–18 due to the unsustainability of the system. This should be yet another warning sign to those who say pensions are guaranteed by raising taxes and implementing monetary policy. It does not even happen in Japan.

Of course, Japan has low unemployment, but that has been the case for decades. The combination of an aging population and cultural challenges for immigration keeps the workforce tight.

However, social security contributions fail to cover even a portion of the expenditure in public pensions. Additionally, at 36 percent, Japan has one of the lowest replacement rates in the world (the percentage of the last salary paid as public pension).

And that is the big lesson. Countries try to solve with monetary measures the impact of much more relevant trends, such as demographics. Increasing taxes and disguising the problem and introducing massive useless stimulus plans only postpones the inevitable crisis.

Some might say “who cares” because there is no inflation. However, real wages in Japan are at a two-decade low and disposable income continues to erode.

The only real beneficiary of Japan’s monetary mirage—which is a slow robbery of the saver under the false pretense of the “social contract”12—is the government, which keeps increasing debt without addressing structural reforms, the challenges of productivity, and “special interests.”

The Justification

There is a small, but relevant, group of economists that justify this policy on various grounds.

The first is the social contract. Debt does not matter because if it preserves low unemployment and high welfares spending it is a success, and the cost is very low because it is almost fully monetized.

The second is the magic of making debt disappear through monetization. On one side, debt in private hands is falling rapidly. On the other, the government never has to repay this debt.

There would be a merit to this if the reality of stagnation did not come back to bite.

The argument is that the effective public borrowing burden is plunging by as much as the equivalent of 15 percentage points of GDP a year. The government debt is shifting from private hands to the central bank. As such, the “debt excluding the QE stock” would be falling. Magic.

It just does not work.

First, even with this argument and ultralow rates, the government spends an extraordinary amount of funds from the budget—almost a quarter—and more than 40 percent of tax revenue on interest payments. And this with a policy of almost zero interest rates for two decades.

Even if we assume low inflation and no other distortions, this extraordinary expense means more taxes in the future and weaker growth.

But it does not work either as a “hide risk under the carpet” argument. It makes the BoJ’s role as a massive hedge fund, self-perpetuating. If the BoJ stopped or even reduced the pace of asset purchases, the marginal buyer is more than questionable. See Figure 5.4.

Who would buy Japanese 10-year bonds at close-to-zero coupon if the BoJ would not be a guarantee of buyer of last resort? But, more importantly, which investor would buy Japanese equities with weak earnings, poor return on invested capital, and low growth if the central bank stopped buying? Of course, there would be a marginal buyer, but at significantly lower valuations than today. It is not a counterfactual assumption. It is a proven historical fact that the stock market plunges when stimulus fades. See Figure 5.5.

Figure 5.4 Nikkei Index vs. Bank of Japan balance sheet

Source: BoJ, Bloomberg.

Figure 5.5 Correlation of the Nikkei index with public-sector spending in the stimulus before Abenomics

Source: Trading economics.

There is no “hiding under the carpet” such an imbalance. The same argument was used about hedge funds and the housing bubble, when commentators believed that syndication and spreading the risk made it less evident. This massive problem will explode. It is just being artificially postponed.

The Demographic Time Bomb

Japan’s nominal GDP growth has been virtually zero in the last 25 years, while public debt has tripled to 230 percent of GDP.

Although Japan pays very little, circa 0.1 percent, for its 10-year bonds, interest payments take almost 22 percent of the budget.

We mentioned the demographic time bomb. Japan has been losing inhabitants for years, and in 2016 had the lowest population since 2000. Not only does it lose inhabitants, but it ages very fast. The segment between 15 and 65 years has fallen by four million people since 2008, while inhabitants older than 65 have increased by the same number. That is why the country spends almost 30 percent of the budget in social security and pensions.

But there is another relevant factor in the corporate structure.

The Corporate Status Quo

Japan’s corporate landscape is comprised of a few large industrial conglomerates, many created in the prewar period with strong ties to the emperor and the government, and 90 percent SMEs, which employ around 70 percent of the private labor force.

The corporate structure is still predominantly divided between the Zaibatsu—large industrial conglomerates—and the Keiretsu—subcontractors—which jointly, and according to many commentators, create a powerful force of intertwined interests with the government, aimed at providing stability and a joint country strategy and helping one another in different matters through time. The “special interests”—kept and supported because, at the same time, all of them have a commitment to labor stability and social welfare.

According to professor Michihiro13 these Zaibatsu remain interlinked horizontally. Before the Second World War, many had strong ties to the military industry, and were dismantled by the U.S. Army, reviving as oligopolies after the war. There were four of these: Mitsui, Mitsubishi, Sumitomo, and Yasuda.

As a side note, the common perception that in some ways the war and the military industry were main contributors to innovation is simply exaggeration. Yes, for example, the Internet and Silicon Valley were a direct result of World War II and the Cold War, but then so were the atom bomb and nuclear weapons. Motor companies thrived during wars and after. Examples of this questionable link exist in Thyssen and Georg von Siemens in Germany; in Henry Ford, Alfred Sloan, and the two Thomas J. Watsons in the United States; and, in Sakichi Toyoda, Masatoshi Ito, and Toshifumi Suzuki in Japan.14

This old-school approach to sociopolitical capitalism worked for a time. It has not done so for more than two decades now. While stability exists, it can easily be confused with obsolescence, and social welfare commitments remain at odds with impoverishment in real wages and a very hard working environment.

This formula of large conglomerates with subcontracting vertical ties to other groups gave the Japanese capitalism strength, a single purpose, and extreme loyalty from workers. But such a model cannot last when the priorities shift from growth and productivity to fighting to keep the system at any cost.

In the book The Fable of the Keiretsu15 we can see that the corporate model is not too different from the French economie dirigée or the Spanish and Italian conglomerates with large banking shareholders.

This model of creating large conglomerates from semistate-owned companies and with blocking minority shareholders, which works as the “poison pill,”16 is also typical in Europe. Since 2001 these models have proven to provide neither growth nor stability.

These structural problems are not covered by printing money. In fact, it makes them worse. When real wages sink, the ability of young generations to spend, have children, and improve economic activity also collapses.

Japan’s solution is easy and at the same time impossible: Completely halt the corporate-financial-government chain of perverse incentives and the unproductive stimulus, concentrate on supply-side policies, lower taxes, cut red tape, and facilitate SME growth as SMEs represent 90 percent of the companies and 70 percent of jobs; such measures attract foreign investment and external workforce. But cultural and historical disincentives weigh too much.

We should see Japan as a warning sign, because the EU is copying the same mistakes but without Japan’s labor discipline and technology.

1 Yasunari Ueno (Mizuho).

2 Japan’s three arrows of Abenomics continue to miss their targets. www.the-guardian.com/business/economics-blog/2015/nov/16/japan-three-arrows-abenomics-recession-economy-targets-shinzo-abe

3 If You Build It ... Myths and realities about America’s infrastructure spending. Edward L. Glaeser, 2016.

4 CNBC comment.

5 Bloomberg.

6 How Japan’s national debt grew so large http://ritholtz.com/2013/10/how-japan%C2%92s-national-debt-grew-so-large/

7 Credit Suisse, 2013, Japan Implications.

8 Bank of Japan, Treasury Budget 2017.

9 A Ponzi scheme is a scam by which investors are promised a strong return which is paid by the inflow of capital from new investors, not by higher profits.

10 Exchange-Traded Funds.

11 Filings, Bloomberg, Reuters.

12 The social contract is supposed to be the guarantee that future generations will continue to support the costs of welfare and repay the debt.

13 Sindo Michihiro: Japanese management in capitalist Japan (1994).

14 Creating Modern Capitalism, How Entrepreneurs, Companies, and Countries Triumphed in Three Industrial Revolutions. Thomas K. McCraw. Harvard University Press, 1998.

15 The Fable of the Keiretsu: Urban Legends of the Japanese Economy, Yoshiro Miwa, J. Mark Ramseyer.

16 Poison pill: Corporate structure in which the Company is impossible to be taken over not because of its strength, but because of a blocking minority of shareholders with same interests.