BUILDING TRUST IN EXTRAORDINARY TIMES

Consider three people:

Rachel is a vice president of sales and marketing for a Fortune 50 company. The company recruited her a year ago in large part because of her impressive track record with its top competitor. Her move was the result of years of hard work and patience, and from Rachel’s perspective it was a well-deserved reward. She had finally earned a senior-level job at a powerful company, had creative and talented management teams to lead, and was eager to enjoy all the perks of hitting the corporate big time.

But all is not well. Rachel is struggling to meet sales and revenue goals, a major initiative to reorganize the global sales force has run aground, the new advertising campaign has garnered lukewarm response, and employee turnover has accelerated in recent months. Rachel is angry, confused, and frustrated at what she perceives to be a lack of commitment from the people in her marketing department, who in her words “won’t get with the program,” and from salespeople who are resisting the changes she is implementing.

Antonio is the top administrator in a state office of health and human services. Trained in social work, he spent just two years as a caseworker before moving into an administrative role. Antonio has become a skilled manager and effective politician, able to maneuver effectively through local, state, and federal bureaucracies. He’s well liked, and he has considered running for public office. But his political ambitions are on hold because he currently faces the toughest challenge of his career. Because of budget shortfalls and pressure for smaller, leaner government operations, Antonio is orchestrating a massive reorganization of his agency that involves a major reduction of employees. As a savvy administrator, Antonio knows what needs to be done, and he’s working hard to figure out the best way to do it.

Even though he’s the architect of most of the change, Antonio is increasingly anxious about his ability to make it happen. He feels it’s important, as he puts it, to “put a good face on the change” and to demonstrate “100 percent commitment to the direction we’re headed.” Usually very social and engaging, Antonio has kept to himself lately. Uncharacteristically, he’s been lashing out when anyone questions his tactics. He feels burned out and is considering leaving public service after the reorganization.

Mitchell was the director of R & D for a small, highly successful biotech firm that was recently purchased by a major pharmaceutical company. A key driver behind the purchase was the perceived value of the smaller firm’s work. Mitchell and his colleagues were relieved to learn that they would remain as an intact unit in the larger organization and that no one would be laid off. Even so, the transition has not gone as well as expected. After a three-month honeymoon, company headquarters and the company’s main R & D unit started to make noises about how Mitchell’s group needs to change its focus.

Mitchell finds himself as the go-between, supporting and speaking for “his” people while negotiating the new environment. He and his R & D team sometimes miss the days when they could just “do the work and not worry about politics,” as he describes it. Mitchell is eager to make the transition successful. He’s willing to explore the implications and benefits of changing course, but he’s also comfortable pushing back and speaking openly to the powers that be in the parent company. He thinks the situation will get better when his colleagues stop comparing the present circumstances to the past. He also realizes that his team needs more time to find its legs so that it can stand up to outside influences and have a more powerful voice in the debate.

Leadership in Extraordinary Times

The leadership pressures that managers like Rachel, Antonio, and Mitchell face are characteristic of current organizational life. Certainly, a crisis or a difficult situation creates extraordinary pressure on organizations and their leaders. But those special circumstances are not required for the emotional pitch of a leadership situation to be shifted. Rachel’s new high-profile role, Antonio’s restructuring initiative, the acquisition of Mitchell’s company—these kinds of events take leaders out of their emotional comfort zone. Leaders face intense pressure to achieve results, putting new expectations and tough demands on themselves and their organizations. In addition, countless sources strain the overall working environment: the economy, unemployment, pressure to do more with less, new challenges of working globally, post-9/11 domestic and international concerns, rapid technological advances, and so on. The reality is that the nature of leadership today is, by and large, bound up in the lurch and sway of change and transition—what we call extraordinary times.

Paradoxically, the dynamic of extraordinary times in organizations is becoming commonplace. Most organizations are experiencing waves of change, one upon another upon another. And their people must make the transition from one organizational reality to the next, over and over again. Managers are so steeped in change as the norm that often when we ask them, “How are you handling the change?” they reply, “Which one? What change are you talking about? There are so many.” Rapid, repeated change and constant transition create an emotional dynamic in organizations. Individuals and organizations are running at a higher emotional pitch than they have in decades past.

So what is the impact of extraordinary times on leaders and leadership?

The primary impact is that leading is categorically different when people’s emotions are stretched and stressed. Extraordinary times make it both more critical and more difficult for executives to focus simultaneously on managing the business and providing effective leadership. More often than not, it is the focus on the people side of leadership that loses out.

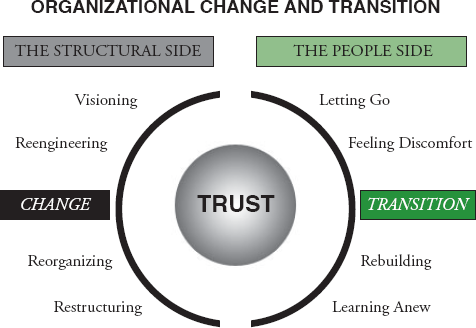

Many managers have mastered the structural side of leading change: creating a vision, reorganizing, setting strategy, restructuring, and so on. They are educated, evaluated, and rewarded on the basis of their dealing with structural challenges and so have more experience with that aspect of organizational change. But they commonly overlook the human side of change—what people need to let go, to build hope, and to learn. That’s not to say that these managers are not aware of the human side of change, but too often they don’t lead their people in a way that reflects their understanding. Unlike structural changes, which can be handled in an abstract and detached way, the human side of change has to be addressed from the inside out. It is precisely because of the extraordinary changes, stresses, and pressures generated by structural or operational changes that people’s needs for leadership are greater. The real challenge to leaders in this position lies in managing the long-term aspects of recovery, revitalization, and recommitment.

Leaders often tell us they would like to pay greater attention to the emotional or human elements of leading change, but they see those as secondary when compared to the more tangible, bottom-line business practices and demands that also require their attention and leadership. But in fact, leaders who minimize or ignore the powerful emotional undercurrents that accompany change and transition risk the bottom line. Perfectly good strategies and change initiatives stall or fail when employees are not committed and engaged. Leaders who fail to gain sufficient buy-in from employees by connecting with their emotional dynamic slow and undermine their progress toward new goals. They may also destabilize the organizational culture by eroding the trust and values that establish and maintain employee dedication. Instead of a loyal, productive, and enthusiastic workforce, executives and managers must lead employees who are insecure, fearful, and skeptical. Their employees are compliant but not committed. And commitment is necessary to make a successful transition.

Valuing Authenticity

We’ve disappointed managers who have turned to us for a simple diagnosis and five-step program for effective leadership in extraordinary times. We’ve frustrated HR professionals seeking the big tool or the research-proven quick fix for organizational malaise. We’ve let down executive teams looking to jump-start a change initiative that has stalled. All of them and many others come to us looking for best practices, saying, “Just tell us what to do.” And we tell them that there is a better way to approach both the structural and people sides of an organization in transition. It’s potentially more powerful, more far-reaching, and more hopeful than any prepackaged kit of best practices. We also tell them that it is challenging, it is ongoing, and it begins with a focus on leadership not as a way of practice, but as a way of being authentic and straightforward amid the emotional sway of change. Authenticity in a leader generates trust from others. Trust is an elusive quality, but in its absence almost nothing is possible. From a position of trust, a leader can more effectively guide others through change and transition.

Building authenticity into your leadership requires that you see both yourself and others as the complex, whole people you are—emotions included. This perspective takes into account that, during times of change, you and everyone else in the organization are collectively steering a course through the events that surround you, but all of you are navigating individually and in the context of your own lives.

Who you are and what you bring to a situation make a big difference in how you deal with that situation. When different people are faced with the exact same set of circumstances, they are likely to respond in different ways. As a leader, your ability to appreciate that and to lead people with that in mind is an important part of leading effectively in extraordinary times.

Self-awareness and a focus on learning underlie authenticity. Certainly, managers and executives should recognize their strengths and weaknesses. But authenticity calls for a deeper recognition and a closer attention to your emotions, expectations, struggles, motivations, preferences, frustrations—even the contradictions they may hold. Leading with authenticity flows from this foundation of self-knowledge and embraces a commitment to learning. Those who lead with authenticity recognize that what they need to learn about themselves, their organizations, and others is continual, and they find ways to learn and grow through feedback, action, experience, and reflection. In times of change, people look for leaders who can appreciate their vulnerability and inspire them, understand them, support them, and guide them through the valley of chaos. Leaders can meet those needs by being genuine and vulnerable, traits that are themselves powerful learning triggers.

Change and transition are not the same thing. Transition represents the psychological and emotional adaptation to change. In our work situations, as well as other areas of our lives, adaptation is essentially a process of letting go of the old way and accepting the new way. Leaders need to recognize that when change initiatives are not going well, it is probably because people are stuck in some part of the transition. They may not be ready to let go because what they have to leave behind was comfortable and it worked. They may not be ready to accept because learning is never pain free—there is a drop in competency and comfort at the initial stage of the learning curve. People resist when they feel at risk. They are grieving because they are letting go of something they value and are trying to adapt to something that is unknown. When people feel this way, they aren’t able to fully appreciate and to actively commit to a change initiative. Trying to solve the problem by focusing only on the structural side of leadership—reiterating your plans and rationale, pushing the data or measurements—doesn’t help resolve the troubles that are connected to people’s difficulty with transition. Instead, your leadership task is to connect to the personal and the emotional fallout of change so that you can help individuals in the organization let go, deal with the discomfort, rebuild, and learn.

Leading Change

Here’s what frequently happens in an organization when a change initiative is put into play: Accustomed to the structural side of leadership—visioning, reengineering, reorganizing, and restructuring—senior leaders see problems and opportunities, and come up with ways for the organization to deal with them. Skilled managers look at direction, structure, operations, and other factors, and then develop a plan of action. Goals are set, processes are revamped, jobs are redesigned or eliminated, and new metrics are established—all under the umbrella of “change initiative.” All the while, leaders often mask their own emotional response to the change in an effort to maintain an image of strength.

Then, with some recognition of the importance of commitment and communication, the organization’s leaders roll out the new plan/process/structure/strategy. For a large-scale change, announcements, meetings, newsletters, and other communication channels become part of the process. When the situation involves more modest or narrowly focused changes, the organization’s leaders often make them with little or no notice and with little or no awareness of unintended consequences. When communication occurs, it is driven by or tuned to legal ramifications.

Having introduced the new way of work, the leaders who are responsible for the plan or for catalyzing the change are usually ready to move on—or they feel compelled to act as if they are ready to move on. They have a plan, they know what to measure, and they know how to proceed. Most managers are focused on leading the structural side of change, represented by the left side of the diagram on the preceding page. That’s how leadership has been defined for them, and what they’ve been rewarded for.

Unfortunately, the best-laid plans for organizational change are frequently diluted or damaged by a failure to exert strong leadership around the people issues. Sooner or later, leaders see that the change isn’t working according to plan. Individuals are not performing as needed and are even resistant. In response, leaders naturally turn to their strengths and habitual ways of behaving. They reiterate the logic of the change and push people harder. They try to motivate people by cheerleading, getting angry, threatening. They get impatient when employees won’t get with the program. Frustration grows as leaders wonder why employees can’t just do what needs to be done. Usually, the organization sheds the more resistant employees, which raises the pressure on and anxiety in the people who remain.

Over the years, we’ve observed this scenario repeat itself time and time again. Senior leaders from multinational corporations, government agencies, small and midsize businesses, and nonprofit organizations have come to us for help when they hit this point and did not realize the benefits they had expected to see. Our diagnosis of the symptoms is often the same: change initiatives break down because people stall somewhere during the transition.

Leading Transition

Organizational events—restructuring, mergers and acquisitions, and financial difficulty—as well as overall uncertainty trigger all kinds of behavioral and emotional reactions. Confronted by change, people go through a time of transition. This adaptive process occurs at a different pace and in various ways for each individual, depending upon the circumstances. In an organization undergoing change, the leader’s responsibility is to live through this process of transition with others in a genuine and authentic way, and to lead in a way that helps bring people through transition so that they can adapt and contribute in the long term.

Leaders who are best able to cope with transition are in touch with their personal reactions to change. They are comfortable sharing those emotions. But such leaders are not the norm. Most leaders have focused little attention on understanding and learning from their own emotional transitions and therefore are not well prepared to foster such efforts in others. When leaders have reservations, a sense of loss, fear, or some other emotion tied to change and their role in it, they need to pay attention to that emotion. Otherwise, they limit their ability to lead with authenticity and to help others cope and adapt.

Building Trust

Even managers who do recognize the emotional power that transition exerts over both them and those they lead rarely have a framework or starting point for coping with the transition. Leaders are most effective in times of transition when they incorporate both structure- and people-related behaviors into their roles and responsibilities. By striking the right balance between the two, leaders build and reinforce trust—a core ingredient for effective leadership.

Without trust from others, leaders can get, at best, a degree of compliance. But only with trust can they elicit genuine commitment from people, particularly during stressful, uncertain times. The challenge of creating an environment of trust is rooted in how difficult it is to earn that trust and how easy it is to damage it.

Leading with authenticity in times of transition isn’t a process of checking off a list of steps or tasks, or of saying the right words. It’s about looking inward and seeing honestly how your personality, behaviors, and emotions play out as you take on a leadership role. It’s about valuing and building trust, understanding the dynamics of change and transition, and discovering openness and vulnerability. Next, we turn to specific leadership competencies that help leaders make these concepts real.

Authenticity: A Foundation of Leadership

Authenticity in a leader generates trust from others. And from a position of trust, a leader can more effectively guide others through change and transition. We’ve identified three steps you can take to begin to grow as an authentic leader in extraordinary times.

1. Examine your mental models. In The Fifth Discipline (1990), Peter Senge writes, “Mental models are deeply ingrained assumptions, generalizations, or even pictures or images that influence how we understand the world and how we take action.” We all have mental models of leadership that have become part of our habitual patterns of thinking, perceiving, and behaving. By becoming aware of your assumptions about leadership, you can make conscious choices about how you want to operate as a leader. If these assumptions are left unexamined, however, you repeat patterns that may or may not be serving you well, especially during challenging times.

2. Understand that change is not transition. In The Way of Transition (2001), William Bridges describes change as a new way of doing something, transition as the psychological adaptation to the change. Bridges explains that transition starts with an ending. Rather than immediately getting on with the new circumstances, people face a period of adaptation. Leaders need to realize that the transition process involves a time of difficulty, often fraught with self-doubt, ambiguity, and uncertainty. People may be reluctant to accept the reality that something is ending, refusing to let go of the familiar and learn about the new. When you or someone in the organization is struggling with change, take time to acknowledge transition by exploring what has been lost and what is getting in the way of adapting.

3. Improve your ability to learn. Most of what you need to know about leading through transition you will learn from experience. If you can learn and adapt (and help others to do so), not only will you recover from change and loss, but you can actually thrive. By becoming a more versatile learner, you increase your capacity to cope with change, adapt through transition, and move on to what’s next.

Keeping True: Leadership Competencies for Extraordinary Times

We often use the image of a bicycle wheel to describe the leadership competencies that are important during times of transition. On a bicycle wheel, each spoke needs to be tightened or loosened to the right tension. Otherwise, there will be strain on the other spokes, pulling the wheel out of alignment and making the bike much more difficult to ride. Avid cyclists keep their bikes rolling at top performance by “truing” their wheels—adjusting the tension of the spokes—as part of their routine bicycle maintenance.

Imagine, now, a wheel that has trust as its hub. Radiating out from that hub are the spokes, which represent twelve competencies that support authentic, effective leadership in times of transition. Six spokes represent structural competencies; the other six represent people-related competencies. Any of the twelve competencies can be overdone, underdone, or held in a positive, dynamic balance (as the spokes on a bicycle wheel are set in a balanced tension). If a leader neglects or devotes an overabundance of energy to any one element, he or she runs the risk of skewing the opposite, pushing the wheel out of true and creating undue strain on the trust needed to lead effectively during extraordinary times.

It’s easy to get out of true—in both cycling and leadership. But while a cyclist can stop riding to fix a wheel, leaders have no choice but to make adjustments as changes swirl around them—in the middle of the ride, so to speak. Adding to their difficulty is the fact that experience and its lessons are coupled with personal preferences to exaggerate or downplay various leadership practices. This often pushes leaders toward emphasizing just three or four leadership competencies—usually the ones that they have been schooled in, the ones organizations reinforce and reward. As a rule, those competencies fall on the structural side of change management. When leaders pay less attention to the people side of change, the tension between the two sides of the wheel can slip out of balance and negatively impact their effectiveness, how they are perceived, and the trust they require to guide people through the phases of transition.

Oftentimes, people are hypersensitive during times of stress and threat. Using our metaphor of the bicycle wheel, people won’t likely say, “You have a few spokes that need attention and tuning,” when they experience a ride on your bicycle. They are more likely to generalize and say, “Your bike stinks.” In the same way, people can make sweeping judgments about authenticity and genuineness based on small cues and data. To lead with authenticity, effective managers develop new behaviors and find appropriate ways to work with the structural and the people sides of change. They don’t swing wildly from one end to the other. By learning about the twelve change-related leadership competencies described in the following chapters and how they relate to each other, managers and executives can tease out adjustments to maintain or improve their level of trust and effectiveness as situations change.

Understanding the Competencies

Each of the following chapters addresses a pair of competencies, showing what each competency looks like when it is overdone and underdone, and what the right balance between the two looks like. Each chapter also provides some guidelines that managers can use to develop each competency, and a simple way to gauge which competencies they need to emphasize during extraordinary times. We begin with an overview of the twelve competencies:

Catalyzing change is championing an initiative or significant change. A leader who is skilled at catalyzing change consistently promotes the cause, encourages others to get on board, and reinforces those who already are. Such leaders are highly driven and eager to get others engaged in new initiatives.

Coping with transition involves recognizing and addressing the personal and emotional elements of change. Leaders who are able to cope with transition are in touch with their personal reactions to change and transition and make use of that emotional information. They lead by example.

Sense of urgency involves taking action quickly when necessary to keep things rolling. Leaders who have a strong sense of urgency move fast on issues and accelerate the pace for everyone. They value action and know how to get things done.

Realistic patience involves knowing when and how to slow the pace to allow time and space for people to cope and adapt. Leaders who display realistic patience appreciate the fact that people learn and deal with change differently and do not judge them based on their own styles, preferences, or capabilities.

Being tough denotes the ability to make difficult decisions about issues and people with little hesitation or second-guessing. Leaders who are comfortable and secure with themselves can display toughness; they’re not afraid to take a stand in the face of public opinion or strong resistance.

Being empathetic requires taking others’ perspectives into account when making decisions and taking action. Empathetic leaders try to put themselves in other people’s shoes; they’re able to enhance their own perspectives by considering the views of others.

Optimism is the ability to see the positive potential of any challenge. Leaders who exude optimism can communicate and convey that optimism to others.

The combination of realism and openness denotes a grounded perspective and a willingness to be candid. Leaders who practice this competency are clear and honest about assessing a situation and the prospects for the future. They are candid in communicating what is known and not known. When managers exhibit realism and openness, they speak the truth, don’t sugarcoat the facts, and are willing to admit personal mistakes and foibles.

Self-reliance involves a willingness to take a lead role and even to do something yourself when necessary. Self-reliant leaders have a great deal of confidence in their skills and abilities and are willing to step up and tackle new challenges.

Trusting others means being comfortable with allowing others to do their part of a task or project. A leader who trusts others is open to input and support from colleagues and friends. Such leaders respect others and demonstrate trust through a willingness to be vulnerable with them.

Capitalizing on strengths entails knowing your strengths and attributes, and confidently applying them to tackle new situations and circumstances. A leader who knows how to capitalize on strengths trusts the abilities that have generated success, rewards, recognition, compliments, and promotions in the past and uses them in new situations.

Going against the grain entails a willingness to learn and try new things, even when the process is hard or painful. Leaders who can go against the grain are willing to get out of their comfort zones. They are willing to tolerate discomfort if it leads to learning.

You may have noticed in reading these brief descriptions that each of these capabilities is important; at the same time there are some inherent conflicts between and paradoxes among them. That’s because in the face of change and turmoil, people look for leaders who are simultaneously strong and vulnerable, heroic and open, demanding and compassionate. Managing well amid those opposing demands can feel like an impossible balancing act. Finding the right behaviors, tone, and style to lead effectively during times of change is largely about blending characteristics that appear paradoxical, but that coexist as a measure of a leader’s authenticity.

Managing the dynamic tension between opposing competencies—using more of one than the other, or some of both, and being able to move between them with some flexibility and grace—is not easy. The point of stability can be different for different situations and at different points in time (describing all the possibilities is well beyond the scope of this book). Appropriately balancing these twelve competencies is a subtle and fragile process, and it becomes even more so during times of stress. If you develop your facility for a range of behaviors and learn to spot signs that your leadership is out of true, you will be better prepared to lead in times of upheaval and transition. Over time, leaders and their organizations do better if leaders develop an agile resilience, know when it’s necessary to move between opposing competencies, and are able to do so.

Let’s return to the stories of our managers—Rachel, Antonio, and Mitchell—and examine their patterns of leadership behavior to better understand the dynamics of the twelve competencies.

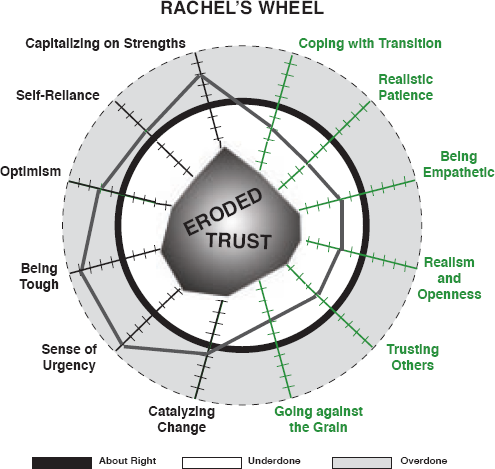

Rachel, the Fortune 50 division vice president, does not have the trust of her employees, and the board of directors is beginning to lose confidence in her. What has happened?

If you look at Rachel’s leadership style as it’s plotted on the wheel on the next page, you’ll see that she significantly emphasizes the structural elements of leadership. The people side of her wheel suffers from her neglect. Convinced she is in the right, Rachel may not realize that her personal frustration and desire to make the change happen are playing out in perceptions that she is condescending, insensitive, and aggressive. Her direct reports say, “She just won’t listen.” She seems oblivious to the depth of her group’s concerns and becomes defensive when someone tries to bring them to her attention. With such a focus on structural issues, it’s clear to others—but not so clear to Rachel—why she hasn’t been able to harness the support, energy, and talent of the people around her. Her direct reports have become conditioned not to speak honestly to her. In their words, “It’s just not safe.”

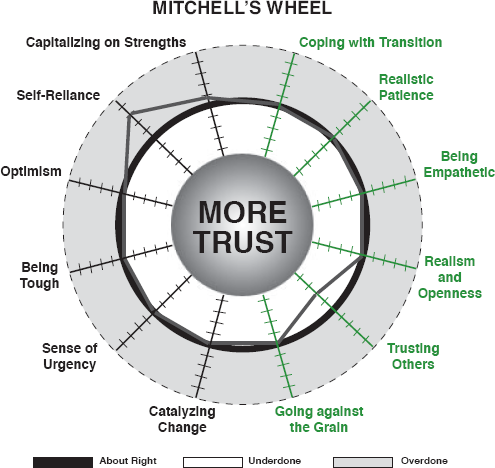

Antonio is struggling with his transition because of a different combination of overdoing and underdoing. When his leadership style is plotted on the wheel below, it’s clear that Antonio’s experience with the people side of leadership is certainly better developed than Rachel’s. However, he tries to shoulder the burden of change by himself, determined to stick with the plan and champion change. Under stress, his behavior becomes more extreme on several of the dimensions, creating confusion among the people with whom he works. He thinks he is protecting his people, but in reality they feel unsupported and frustrated. The organization feels that Antonio is losing his edge. He isn’t implementing his changes and appears not to be holding others accountable. The plan is in danger of falling apart.

Mitchell, in contrast to Rachel and Antonio, is leading himself and others through transition in a balanced, effective way. His wheel, below, is not a perfect circle, but neither is leadership really a bicycle wheel. Maintaining the right balance among the twelve competencies doesn’t mean that Mitchell gives every dimension equal emphasis or that he calculates every word and action. Rather, it indicates that Mitchell has accurately assessed both the business climate and the emotional climate in which he works. He is astute in his political and relational roles and has a good handle on his own emotional reality. Mitchell is able to blend his skills and adapt his approach. Even though his work situation is stressful, he feels authentic, true to himself. His direct reports and others react to his authenticity and see him as an effective leader.

Perhaps the biggest challenge you will face in practicing an authentic brand of leadership is finding the right point of dynamic balance in those areas where your own assumptions about leadership lead you to emphasize one set of competencies over another, particularly in times of stress. These tendencies have their origins in your personality traits, your education, your training, and your lifelong learning experiences. Reaching the right point of balance doesn’t require emphasizing each competency to the same degree. You may find, for example, that a slight increase in your empathy or your openness toward others goes a long way toward resolving the concerns people have over a new process or system. Or you may find that your being more direct and more willing to make hard decisions can provide the clarity and confidence people seek in an ambiguous situation.

Generally, the key to leading with authenticity in extraordinary times is to neither exaggerate nor downplay any of the twelve competencies. However, highly effective leaders can and do intentionally overplay one or two elements to great effect. This tactic works when two things hold true: First, the leader chooses a behavior and is not reacting defensively. Second, the leader astutely pulls closer to true over time. This attention to the situation at hand and the agility required to shift emphasis from one competency to its opposite are hallmarks of a leader whom people trust to lead change.