Problem-based learning and collaborative information literacy in an educational digital video course

Information literacy is a central challenge for students, as multimedia information networks, especially the Internet, are being used more and more as information sources. Information literacy has traditionally been understood from an individualistic perspective as a set of generic skills, but recent research has highlighted the need to study the social construction of information literacy, as well as its context-and content-specific nature (Tuominen, Savolainen & Talja 2005). Different types of information literacy are being formed in different groups and cultures and at different times (Street 2003).

This chapter seeks to demonstrate the social construction of information literacy and its context-and situation-specific nature in an educational digital video course that uses problem-based learning as the pedagogical framework (see also Hakkarainen 2008). It is based on design-based research (Design-Based Research Collective 2003), carried out while the course was designed, implemented and evaluated with the viewpoint of refining the course. The research focused on finding out how the course supported students’ meaningful learning. Special attention was given to information literacy as part of learning (Hakkarainen 2007, 2008, 2009). The study was conducted at the University of Lapland’s Faculty of Education as part of the Web Searching, Information Literacy and Learning (Web-SeaL) project, funded by the Academy of Finland.

The research data was collected through two questionnaires completed by the course students, video recordings of the four problem-based learning tutorial sessions and the stimulated-recall interview organized at the end of the course for the students. The questionnaire data was analyzed quantitatively (mean values, standard deviations, percentages) and qualitatively into themes. The video data of the problem-based learning tutorials was analyzed both quantitatively and qualitatively into Bales-type function categories (Erickson 2006).

We will begin with a short introduction to problem-based learning and information literacy, as understood and defined in this case. We then present the research questions and the research process and consider, in the light of the research results, the relationship between problem-based learning and information literacy.

Problem-based learning and information literacy

The process of problem-solving may be structured in different ways. One of the most famous models was developed by Barrows at McMaster University, Ontario, Canada (Barrows 1985; Barrett 2005). The other well-known model is Schmidt’s (1983) ‘seven jump’ model from the University of Maastricht in the Netherlands, and its variations in many universities. The cyclical model developed at the University of Linköping, Sweden has been applied in many places too. For this reason, it is not possible to identify a single model of problem-based learning (Poikela 2003; Savin-Baden & Howell Major 2004; Barrett 2005). The idea of the cyclical model with eight phases (see Figure 4.1) is tested and further developed in the context of Finnish higher education in several organizations (Poikela 2003; Poikela & Poikela 2005b, 2006). This model is used as an operational procedure in the digital video course as well.

Figure 4.1 Problem-based learning cycle (adapted from Poikela & Poikela 2006, p. 78)

We emphasize, however, that problem-based learning should not be understood solely as a pedagogical approach or model, but rather as a general approach to teaching and learning and as a pedagogical and curricular innovation. In addition, problem-based learning is a unique educational philosophy with its own epistemological and ontological arguments. Carefully designed problems related to working life create a solid base for learning. The tutor facilitates the problem-solving process during tutorials that last two, three, or a maximum of four hours. A problem-based learning curriculum is organized around problems, rather than according to a particular topic or academic discipline. Student-centredness, small-group work, self-directed learning, experiential learning and the tutor’s role as a facilitator have been identified as core characteristics of problem-based learning. In Problem-based learning also emphasizes the crucial importance of critical and reflective thinking skills, contextual knowledge and the integration of disciplines (Barrows 1996; Hmelo-Silver 2004; Poikela & Poikela 2005b, 2006). The importance of assessment and evaluation systems, including students’ self-evaluation, is emphasized (Dochy et al. 2003; Poikela & Poikela 2005b).

A problem-based learning cycle (Figure 4.1) consists of collaborative learning achieved in two tutorial sessions that last approximately two hours each. The first session covers phases 1 to 5 and the second phases 7 to 8. Independent knowledge acquisition (phase 6) is situated between the two tutorial sessions. The tutor and from seven to nine students gather approximately once a week. During phase one, students have to reach a shared understanding of perspectives and conceptions of the problem. The purpose of the second phase is to elicit and elaborate on former knowledge about the problem phenomena. This is achieved by brainstorming ideas about possible ways of dealing with the problem. The third phase starts with connecting similar types of ideas together into separate categories and naming them. During the fourth phase, the most important and actual problem areas (named categories) are negotiated. The fifth phase culminates in the first tutorial session, the aim being that students form the learning task and the objects of study.

The sixth phase is a period of information seeking and self-study between tutorials. Students work both alone, and in small groups, depending on the learning tasks and aims. The second tutorial begins the seventh phase. It is a practical test to use new knowledge. Freshly acquired knowledge is used to tackle the learning task, and is then applied in constructing the problem in a new manner. New knowledge will be synthesized and integrated at a more advanced level, and provides a basis for learning to be continued. During the eighth phase, the whole process of problem-solving and the learning process is clarified and reflected in the light of the original problem.

Unlike several other tutorial scripts (for example, Hmelo-Silver 2004; Moust, Van Berkel & Schmidt 2005), assessment, placed in the middle of Figure 4.1 above, is not included as a separate phase; rather, it is part of each phase. Tutorial sessions close with a feedback and assessment discussion, during which students get information and feedback about their learning, group processes and problem-solving skills (Poikela & Poikela, 2006, p. 79).

Students’ information-seeking skills may require a great deal of improvement when starting with problem-based learning. It is not enough for tutors to simply ask students to go and find information from the library or the Internet. It is essential that tutorials include discussion about where the most relevant information could be sought and what the most important resources are. Acquiring information and becoming familiar with different kinds of information environments need practice and assistance. Librarians and informants are specialists whose help is needed too (Poikela & Portimojärvi 2004; Poikela & Poikela 2006).

The importance of virtual and web-based environments is increasing as forums for finding, sharing and evaluating information resources. For example, social media (Web 2.0), including the idea of collaborative knowledge building, are the most rapidly developing phenomena in the web. 1 am using social media here to refer to web services that receive most of their content from their users. The various web services of social media can be categorized into different genres, such as content creation and publishing (for example, blogs), content-sharing (for example, YouTube), social networking (for example, Facebook and MySpace), collaborative productions (for example, wikis) and virtual worlds (for example, Second Life and Habbo Hotel) (Lietsala & Sirkkunen 2008). These services are widely used by the younger generation and it is, therefore, only natural that the possibilities that social media offer should also be seriously considered by the educational sector (Poikela & Portimojärvi 2004; Manninen et al. 2007; Poikela, Vuoskoski & Kärnä 2009).

The concept of information literacy is the focus of lively discussion and debate (Breen & Fallon 2005; Tuominen et al. 2005). The standards of information literacy and associated indicators put forward by the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL 2000) are among those most used and cited. According to these standards,

an information literate individual is able to:

• determine the extent of information needed

• access the needed information effectively and efficiently

• evaluate information and its sources critically

• incorporate selected information into one’s knowledge base

• use information effectively to accomplish a specific purpose

• understand the economic, legal, and social issues surrounding the use of information, and access and use information ethically and legally (ACRL 2000, pp. 2-3).

Information literacy is one of the expected learning outcomes, as well as one of the factors contributing to learning outcomes (Breen & Fallon 2005; Hakkarainen 2007, 2008, 2009). Information literacy pertains centrally to the qualifications required in working life: independent knowledge acquisition; knowledge application; multi-professional skills; ability to learn constantly; critical and creative thinking; and collaboration and problem-solving skills (Poikela & Nummenmaa 2004; Tynjälä 2001). Information literacy research seems to follow a similar trend to recent learning research. In both areas of research, the focus has shifted to the interaction of groups and communities and to the processes through which the knowledge and skills that the research focuses on are being collaboratively defined and developed.

In the light of both research (for example, Eskola 2005; Rankin 1996) and practical experience (for example, Breen & Fallon 2005), problem-based learning has been found to be a meaningful and successful learning environment for information literacy. Integrating information literacy teaching and guidance into the problem-based learning curriculum is considered a central strategy. In practice, this means increasing the collaboration between librarians and problem-based learning tutors, teachers and students in designing, implementing and evaluating curricula and individual courses (Breen & Fallon 2005; Poikela & Poikela, 2005a; Rankin 1996).

Course description

The research focused on a course called ‘Digital Video: Supporting Meaningful Learning through Using and Producing Digital Videos’. It is a new and optional course for a Master’s Degree in Media Education at the University of Lapland’s Faculty of Education. The students receive five European Credit Transfer System (ECTS) credits for completing the course, which is graded as pass/fail. The course is the first course in which problem-based learning is applied in the Media Education curriculum. The primary aim of the course is to make students able to use and produce digital videos in a way that supports meaningful learning. In addition, students should learn how to negotiate copyright issues related to digital video productions. A special feature of the course is that students will produce, in pairs or in small groups, educational digital videos as commissioned works for Faculty teachers. The students take care of the whole production process: developing ideas; writing the manuscript; shooting; editing; and negotiating copyright issues. As their written assignment, students write an analysis of the digital video they have produced. The first-named author of this chapter has conducted the research, designed the course and worked as both the teacher responsible and the problem-based learning tutor for the course.

Ten students (seven female and three male), aged between 20 and 36, enrolled in the first implementation of the course in September and October 2006. The students were second-to fifth-year pre-service teacher students and undergraduate students of Media Education. The course started with an introductory meeting, after which the students participated in three problem-based learning tutorial cycles (Figure 4.1) that were realized through weekly tutorial sessions (n=4). The problems to be solved by the students during the problem-based learning cycles were:

1. How can we support meaningful learning by using and producing digital videos?

2. How can we write a script for an educational digital video?

3. How can we avoid the most typical beginner’s mistakes in shooting a digital video?

Between the tutorial sessions, the students engaged in independent knowledge acquisition in workshops on scriptwriting, filming, editing with Microsoft MovieMaker software and copyright issues (twenty-eight hours altogether). In addition, the students used the Internet and the library, attended a lecture, and used their peers and social networks as information resources. The course was supplemented by a web site with links to suggested learning resources and to the digital videos produced by the students. However, the production of the digital videos was not the primary aim of the course; the digital video was, rather, one of the resources of independent knowledge acquisition and the primary aim was problem-solving and learning. At the end of the course, a final assessment meeting was organized.

Data collection and analysis

To promote the validity, reliability and applicability of the research, data of various kinds and from multiple sources was used (Cobb et al. 2003; DBRC 2003; Wang & Hannafin 2005). Because the study focused on a single course and did not seek statistical significance, quantitative analysis was applied as a tool for describing and interpreting the data and for making its internal generalization more explicit. In this chapter we describe the data that was collected and analyzed through the following procedures:

Questionnaire focusing on the learning process and outcomes. Nine of the ten students enrolled in the course completed the questionnaire, which included twenty-three statements concerning the meaningfulness of the learning process and thirteen statements concerning the learning resources and learning outcomes (workshops, problem-based learning tutorials, commissioned video assignment, lecture and the course web site). The students completed the questionnaire two weeks after the course had ended and they had received their grades. They were asked to evaluate the statements using a five-point Likert scale. The construction of the questionnaire and the analysis of the questionnaire data is reported elsewhere (Hakkarainen 2007, 2009; Hakkarainen, Saarelainen & Ruokamo 2007, 2009). The mean values, standard deviations and percentages of the students’ ratings were extracted.

Questionnaire focusing on the independent knowledge acquisition phase. The questionnaire included both closed and open-ended questions which were used to find out: (a) the information resources that students had used; and (b) students’ reasons for choosing these resources. The students completed the questionnaire after the independent knowledge acquisition phase in each of the problem-based learning cyclcs, a total of three times. Nine students completed the first questionnaire, whereas the second and the third questionnaires were completed by eight students. The questionnaire data was analyzed by calculating how many students had used certain resources. In addition, the reasons students gave for their choices of resources were analyzed into themes.

Video recordings of the four problem-based learning tutorial sessions. The video recordings comprised 7.5 hours of video data. The length of the problem-based learning sessions varied from 1.5 to 2 hours. In two of the sessions, five minutes were left unrecorded because the cassettes ran out before the end of the session. One fixed digital camera was positioned at the front of the room to capture the student group and the tutor. The tutor was, however, sometimes outside the camera’s range. First, the recordings were transcribed word for word and nonverbal communication (pauses, silences, laughter, humorous tones, and hand gestures) was also noted. Next, the data was analyzed according to the number of tutor comments and student comments. A comment was defined as a meaningful verbal comment ranging from a short ‘mmm…’ indicating agreement to comments that lasted several minutes. The student comments were then analyzed and coded into Bales-type function categories (Erickson 2006). A single comment could include units that belonged to two or three different coding categories. A total of 2.3% (n=61) of the comments were coded in the category ‘inaudible’, because more than one student was talking at once, or they were talking too quietly, or the technical quality of the recording was inadequate. NVivo qualitative data analysis software was used as a tool in analyzing and coding the data. To enhance the reliability of the coding procedures and categories, the entire collection of video data was first viewed several times and then coded in two rounds.

Video recordings of the stimulated-recall interview. A stimulated-recall interview (Erickson 2006; Marland 1984) was organized two weeks after the course had ended and the students had received their grades. The 1.5-hour interview was undertaken as a group interview in which nine of the ten students in the course participated in the interview. During the interview the tutor-researcher viewed seven video clips extracted from the video recordings of the problem-based learning sessions of the Digital Video course with the students. The students were asked to describe what was happening in the situations that the video clips portrayed and what they had thought and felt during those situations. The tutor-researcher selected the video clips because she thought that they served as a showcase for the collaborative nature of students’ information literacy. The selection was not a result of a systematic analysis. Moreover, the video clips viewed and discussed at the stimulated-recall interview served as possible examples of how the collaborative nature of information literacy can be seen in students’ talk during the tutorials. In this chapter, we describe one of the video clips that the tutor-researcher discussed with the course students.

Research results

What follows is a description of the relationship between problem-based learning and information literacy, especially its collaborative nature, in the digital video course that the research focused on. The structure of our description is based on the ACRL information literacy standards (2000). We discuss how the operational procedure of problem-based learning supports and demonstrates the collaborative construction of information literacy within its different content areas, that is, in determining the extent of information needed, accessing the needed information and evaluating and using information.

Determining the extent of information needed

According to the ACRL standards (2000, p. 2) ‘an information literate individual is able to determine the extent of information needed’. Students have the main responsibility in this; the teacher’s role is not to define the nature and quantity of knowledge that students should acquire or how much they should learn. In the core characteristics of problem-based learning—student-centredness, self-directed learning, and the tutor’s role as a facilitator (Barrows 1996; Hmelo-Silver 2004; Poikela & Poikela 2005b)—this responsibility is clearly apparent. The students’ responsibility is also apparent in the operational procedure of problem-based learning. During the first session, students work through setting the problem (phase 1), brainstorming (phase 2), structuring the ideas generated during the brainstorming (phase 3), selecting the problem area (phase 4) and setting the learning task (phase 5). It is the student group that defines the information that it needs to solve the problem at hand. After this, the student group sets its learning task for which it seeks answers during the independent knowledge acquisition stage (phase 6). In the problem-based learning cycle, determining the extent of information needed is most clearly realized in phases one to five. The student group defines the information needed with respect to what they already know about the problem at hand and its solutions. Constructive characteristics are therefore realized in the problem-based learning cycle, which could be seen in the high ratings (M=4.44–4.67, SD=0.5–1.73) that the students gave for the statements measuring the constructiveness of the learning process (Table 4.1).

In the questionnaire, the students stated that their role was to actively acquire, evaluate, and apply information (M=4.67, SD=0.5). Out of the characteristics of meaningful learning applied in the research, activeness also entails students’ attitude towards information and knowledge. An active attitude towards information and knowledge is central both in the ACRL standards, and in problem-based learning. According to Poikela and Poikela (2005, p. 33), in problem-based learning, ‘knowledge is not only an object for memorising, it is a subject and tool for observing, analysing, integrating and synthesising’.

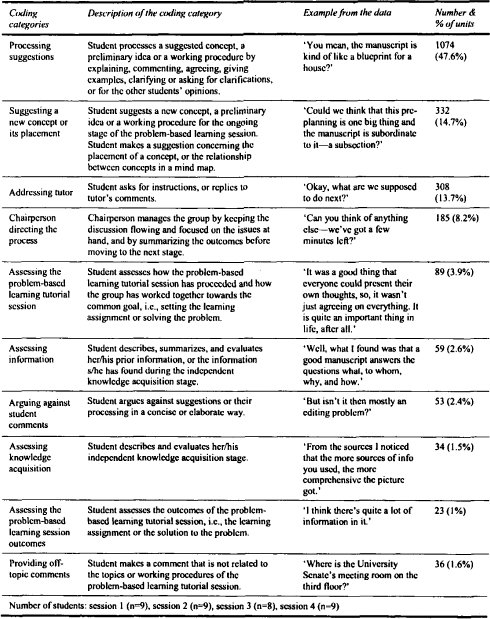

In the problem-based learning sessions, determining the extent of information needed is collaborative (Repo-Kaarento 2004); instead of the individual students, the student group is the subject of the process. In addition, collaborative characteristics were realized in the sense that, in defining the information needed (problem-based learning tutorial phases 1 to 5), the students were processing concepts, ideas or working procedures suggested by their fellow students or themselves by explaining, commenting, agreeing, giving examples, clarifying or asking for clarification. In the four problem-based learning tutorial sessions, the largest number of units (n=1074, 47.6%) was coded in the category ‘processing suggestions’, which clearly indicates that the students were engaged in collaborative and conversational knowledge construction by explaining or commenting on the suggested ideas, giving examples, or asking for clarification or for one another’s opinions.

The results indicate that the students were taking a responsible role in determining the extent of the information needed. Both the analysis of the questionnaire focusing on the learning process and the outcomes and analysis of the video recordings of the problem-based learning sessions support this argument. In the questionnaire, student experience concerning the self-directedness of the problem-based learning sessions was measured through the statement ‘The students directed their own studying process in the problem-based learning sessions’, which the students rated favourably (M=4.44, SD=0.53). The analysis of the video recordings showed that the tutor’s comment units accounted for only 19.2% (n=537) of all the coded comment units (n=2791) of the tutorial sessions. This indicates that the students played a central role. Students’ talk was in a more central role, contrary to a more teacher-centred teaching approach, in which approximately two-thirds of the talking has been shown to be done by the teacher (Ruberg, Moore & Taylor 1996).

All in all, the collaborative, co-operational and conversational characteristics of meaningful learning proved to be the core characteristics of the course, as is typically the case in problem-based learning. This can be argued on the basis of the analysis of the questionnaire data and the video recordings of the problem-based learning tutorial sessions. The students’ ratings on the questions focusing on these characteristics were very high (M=4.44–4.89, SD=0.33–1.01). In the four problem-based learning tutorial sessions, the largest number of units (n=1074,47.6%) was coded in the category ‘processing suggestions’, which indicates that the students were engaged in collaborative and conversational knowledge construction by explaining or commenting on the suggested ideas, giving examples, or asking for clarifications or for one another’s opinions. The second largest number of units (n=332, 14.7%) was coded in the category ‘Suggesting a new concept or its placement’. The percentage of students’ comment units in the coding categories remained approximately the same in all four tutorial sessions. We interpret these comment units as collaborative knowledge construction, which necessitates and, in the best cases, also promotes students’ skills in collaboratively assessing and applying information. As working life requires, among other things, the ability to learn constantly, as well as collaboration and problem-solving skills (Poikela & Nummenmaa 2004; Tynjälä 2001), that students are offered well-guided possibilities in developing these skills is justifiable.

Accessing the needed information

After defining the extent of the information needed (phases 1 to 5), the students moved into the independent knowledge acquisition phase, which lasted about a week in each of the four problem-based learning cycles.

According to the ACRL standards (2000, p. 2), ‘an information literate individual is able to use information effectively to accomplish a specific purpose’. What is meant by ‘effectively’? According to the standards (ACRL 2000, pp. 9-10), the information-literate student selects the most appropriate investigative methods or information retrieval systems for accessing the information that is needed, constructs and implements effectively designed search strategies and retrieves information online or in person using a variety of methods. The student is also able to refine the search strategy if necessary and to extract, record and manage the information and its sources. Out of these performance indicators, the versatility of the information retrieval methods and resources seems to have been realized during the course.

Versatile information retrieval methods and resources

During their independent knowledge acquisition phase, students used versatile material and social resources: workshops given by the teachers of different disciplines; a lecture; and accompanying literature in Finnish. Six out of the ten students had used the video clips that were available through the Internet and were linked into the course web site. In addition, five students had searched Google using Finnish search terms. All students had used the commissioners of their video, that is, the Faculty teachers, as an information resource. In addition, all students indicated that they had used their fellow students and social networks outside the university as information resources.

Previous studies on problem-based learning in medical education have shown that problem-based learning students spend more time in the library and use a greater variety of learning resources (Rankin 1996). An authentic and adequately complex and bewildering problem guides and motivates students to search for information from versatile resources (Valtanen 2005). This seems to have been the case in this course too, although this does not mean that the problems handled during the course do not need to be further developed. An additional challenge of the independent knowledge acquisition phase is to use more working-life experts outside the university as learning resources.

Transgressing one’s comfort zone and the boundaries of competencies

The analysis of the questionnaire focusing on students’ independent knowledge acquisition showed also that knowledge acquisition was limited with respect to scientific articles in English. Reading these articles is essential, since there is at present very little, if any, research literature in Finnish that focuses on the educational use of digital videos. Only three of the nine students who completed the questionnaire had used articles in English as learning resources. The course web site includes links to suggested articles, so it was not a question of the availability of articles. These limitations in knowledge acquisition resulted in students’ difficulties in integrating theoretical viewpoints into their written assignments. Moreover, according to the analysis of the research questionnaire focusing on the learning process and outcomes, the abstract characteristics of learning were not realized to the same extent as the other characteristics of meaningful learning. Students gave the lowest rating to the statement measuring the abstract characteristics of the learning process: ‘On the course practical examples were studied in a theoretical framework’ (M=3.44, SD=1.13).

Integrating theoretical and practical knowledge is central in problem-based learning, as noted by E Poikela (2001, p. 105): ‘Formulating theory requires practical experimenting and understanding practice requires conceptual knowledge’. One of the challenges of the Digital Video course is to increase the amount of guidance that focuses on understanding practice with the help of theoretical knowledge. It seems that there is a need to allocate more hours in lectures and workshops that focus on theoretical viewpoints related to the educational use of digital video.

In addition, students’ scant use of research articles in English spurs one on to consider integrating the teaching of this specific information literacy skill into the course. It seems that students were using resources they were familiar with and could easily access and use (Breen & Fallon 2005). Students should be supported in transgressing their comfort zone.

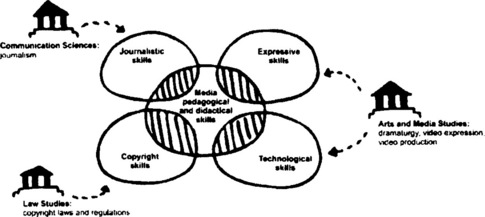

Problem-based learning seems to offer a good model to support students’ knowledge and skills in producing and using educational digital videos. It accentuates the importance of the integration of disciplines and shared knowledge construction for producing multi-professional competence (Poikela & Poikela 2005b). Educational digital video production is a challenging assignment for students from the perspective of knowledge acquisition. It requires that students develop knowledge and skills in multiple domains besides media pedagogy and media didactics, including dramaturgy, video expression, video production, copyright laws and regulations, and journalism (Figure 4.2).

Figure 4.2 Multiple skill domains needed in educational digital video production (cf. Poikela & Poikela 2005a, p. 39).

The core competencies that the course aims at are media pedagogical and didactical skills. In addition, students need to develop some expressive, technological, copyright and journalistic skills. Traditionally these skills have been taught mainly within different disciplines and programs at universities. The results of the pilot study, which focused on the design process of the Digital Video course, indicated that novice Media Education students can experience difficulties in acquiring, evaluating and using knowledge when transgressing the boundaries of their own discipline into arts and media studies, journalism, and law studies (Hakkarainen 2006). This can also be interpreted as transgressing one’s comfort zone. However, the analysis of the video recordings of the problem-based learning tutorials showed that, when transgressing the boundaries of their own discipline, the students experienced the workshops on filming and scriptwriting as more useful information and learning resources. In the workshops, students were practising shooting and preparing the manuscripts with the help of a teacher.

Did the Digital Video course support students’ skills in acquiring and evaluating knowledge? Despite the fact that the students stated in the questionnaire that their role was to actively acquire, evaluate and apply information (M=4.67, SD=0.5), they were less convinced that they had learned to acquire and evaluate information (M=3.56, SD=0.53) and to think critically (M=3.56, SD=1.24) during the course. Students’ role in problem-based learning is to actively acquire, evaluate and apply knowledge. The operational procedure of problem-based learning guides, motivates and even forces students into this role. A central finding of the research is, however, that for the development of students’ information literacy, more goal-oriented and integrated information literacy teaching and guidance is needed.

Evaluating and using information

According to the ACRL standards, an information-literate individual is able to ‘evaluate information and its sources critically, incorporate selected information into one’s knowledge base, and use information effectively to accomplish a specific purpose’ (ACRL 2000, p. 3). Assessment, including students’ self-assessment, is central in problem-based learning (Dochy et al. 2003; Poikela & Poikela 2005b). The assessment realized within the problem-based learning tutorials is both process assessment and product assessment, and it focuses on the different phases of the problem-solving process, learning and group processes.

Part of the students’ comment units in the problem-based learning sessions was clearly assessive in nature. These comment units were coded into four categories. Out of these four categories, two categories comprised comment units assessing the problem-based learning tutorial session (‘Assessing the problem-based learning tutorial session’ and ‘Assessing the problem-based learning session outcomes’) and two categories comprised comment units assessing information and knowledge acquisition (‘Assessing information’ and ‘Assessing knowledge acquisition’). The coding categories are described in more detail in Table 4.2.

Table 4.2

Division of students’ comment units into coding categories in the four problem-based learning sessions (Hakkarainen 2007, 2008, 2009).

All in all, comment units including assessment (n=205) accounted for 9.1% of all students’ comment units. These evaluative comment units centred clearly in the phases following students’ independent knowledge acquisition, that is, during phase seven (‘Constructing knowledge’) and phase eight (‘Clarifying the solution to the problem’). In other phases of the problem-based learning cycle, only sporadic instances of evaluative comments could be found.

Evaluative talk focusing on knowledge acquisition, information and sources

The relative amount of comment units coded into the categories ‘Assessing information’ (n=59, 2.6%) and ‘Assessing knowledge acquisition’ (n=34, 1.5%) was small. These comment units centred on the ‘Constructing knowledge’ phase that took place after students’ independent knowledge acquisition. In the problem-based learning tutorials, the students talked in turns about their independent knowledge acquisition and its results and assessed both of these aspects. Students were provided with a list of questions that they were expected to cover when telling the group about their independent knowledge acquisition:

• How did your independent knowledge acquisition succeed? Assess your own activeness.

• What were the most important things that you discovered during independent knowledge acquisition?

• Based on which criteria did you choose the particular information resources?

• Did the information resources offer you enough information? What information did you miss?

• Was the information you found reliable, accurate, current, suitable for your own purposes?

Although there were not many instances when students assessed information, they demonstrated, however, that students were evaluating information and its sources, as well as incorporating selected information into their knowledge base (ACRL 2000, pp. 2-3). The following excerpt illustrates this. In the excerpt, a student assesses the Citizen Kane movie script she has found on the Internet. The student assesses the script with respect to the value that it may provide for the group’s learning.

Student 7: The Internet part actually ended up with me finding the script of Citizen Kane. I started reading it, saw that in the ‘50s [laughs]. They were pretty thorough back then too—they were professionals when you think of it. The shooting scripts say exactly what angle the camera comes down at, exactly what path it follows coming down and where it goes through [shows with hands]. The directions are very detailed, so we have to be too, even though were just novices in this business.

During the stimulated-recall interview, students discussed difficulties that they had experienced when assessing their independent knowledge acquisition in turns during the problem-based learning tutorials. They reported having themselves experienced, and having seen other students experience, difficulties in summing up the results of their knowledge acquisition into a concise comment. The rounds of comments in the problem-based learning tutorials took a long time and, in the video recordings, it could be seen that students were at times getting tired of listening to each other’s lengthy comments. The questions for the assessment of independent knowledge acquisition were not provided for students until after the knowledge acquisition phase. In the future realizations of the course, they should be given to the students beforehand. More emphasis should also be put into guiding students to sum up the central findings of their knowledge acquisition into concise comments. In addition, a web-based environment, for example, a blog, could be used by the students to share and evaluate information found during their independent knowledge acquisition phase (see also Kämä & Kallioniemi 2006). This way, the students could get started at evaluating information during the knowledge acquisition phase, and not after it.

However, the students reported that the experience of listening to other students discussing and assessing their knowledge acquisition was useful for their own learning. Students’ comments during the problem-based learning tutorial were collaborative, in the sense that students focused their comments in relation to the comments of other students—they had to think what kind of knowledge had already been presented by others, and what new knowledge they could bring to the conversation.

Based on the results of this research, guiding students to critically assess information and its sources can be seen as one of the development needs of the Digital Video course. The analysis of the questionnaire focusing on the learning proccss and outcomes revealed that students gave the second lowest rating to the statement focusing on the critical aspects and characteristics of the learning process: ‘The studying developed my critical thinking skills’ (M=3.56, SD=1.24). In the ACRL standards, critical assessment of information is central.

How should we better guide students in critical thinking, including the critical assessment of information, in the Digital Video course? One way is to have students collaboratively perform a critical media analysis of the digital videos they have previously produced. Media presentations do not mirror reality, but instead are constructed representations, which need to be evaluated critically. Pupils’ and students’ own video productions have been shown to have a positive effect on the development of their media literacy (Adams & Hamm 2000; Reid, Burn & Parker 2002; Schuck & Kearney 2006; Shewbridge & Berge 2004). Media literacy and media proficiency are new challenges for education (Ruokamo 2005; Suoranta 2003; Telia et al. 2001; Vcsterinen et al. 2006). According to Telia, media proficiency refers to a more active and productive command of and greater ability to communicate using media and new technologies than the concept of media literacy denotes. Media proficiency entails ethical and aesthetic considerations, as well as a broader understanding than prevails at present of the significance of audiovisual communication (Telia et al. 2001, p. 30; see also Ruokamo & Telia 2005, p. 4).

The analysis of the video recordings of the problem-based learning tutorials suggests that the production of digital videos helped students to understand videos as constructed representations. In phase seven (‘Constructing knowledge’), students explained how writing the manuscripts, shooting and editing the videos had required selecting viewpoints and content.

Student 5: The [camera] angle and perspective the things are presented from. Is it brought…can it be seen clearly or is it ambiguous or…the clearer it is brought out, the more alternatives you have to get a clearer image.

Tutor Are you thinking of broader, sort of critical perspectives in addition to the visual expression? What perspectives for example?

Student 3: Yeah, for me it’s never just how something looks but in a way what content has been chosen for it…

Student 5: It’s those choices you have to make—there are many different situations and you just have to choose one.

According to Suoranta (2003, p. 60), one can ask any media presentation, for example, the following questions, which help to understand media content as constructed representations: What kind of a version about the incident is being told?, Who is the narrator?, From whose viewpoint is the story being told?, What is left untold?, and What kind of rhetoric means are being used? Integrating this kind of media literacy teaching into the Digital Video course seems justifiable and is one of the development needs of the course.

Example: Is an information source from the 1980s still usable?

The analysis of the video recordings of the problem-based learning tutorials showed that the teacher-researcher did not seize on each student comment or other cue, for example laughter, possibly demonstrating the collaborative aspects of students’ information literacy. In a sense, these fleeting moments for discussing and teaching information literacy were therefore ‘lost’. On the other hand, they demonstrate that the problem-based learning tutorials can make the collaborative nature of information literacy visible. They also hint at specific information literacy issues that could be discussed with students in the future and at issues that could be included in information literacy teaching.

Next, we will make a closer examination of one of these ‘lost moments’. This episode took place in phase seven (‘Constructing knowledge’), during which students reported and assessed their knowledge acquisition and its results. We interpret the episode as demonstrating the collaborative nature of students’ information literacy. In the following excerpt, a student is describing her knowledge acquisition and its results in the following way:

Student 8: Yeah. I found a really new [sarcastically] book that came out in ‘84. It’s in great shape. But you’d be surprised—it has pretty much everything. It’s Annamaria Ollikainen’s Koulutelevisiosta videoon [From school TV to video]. It talks about school TV in East Germany [some students laugh] but it has a pretty good—maybe rather old—but what I find to be a good list of the types of AV learning material according to teaching goals. It has…they have fancy names here based on the purposes the materials are used for and when I read through the book last night, there really were sensible things, things you can use even today. And for the most part I looked for material elsewhere than on the Internet, because I figured all the rest of you would be looking there.

Tutor. Could you tell us where you found it?

Student 8:I was pretty surprised, too.

What is interesting is how the student justifies the usability of this book, published in 1984, by saying ‘you’d be surprised—it has pretty much everything’. The book made some of the students and the tutor laugh. Viewing and discussing the video recording of the episode later in the stimulated-recall interview revealed that the students and the tutor shared an understanding about the age of the information source with respect to its usability. Students and the tutor had laughed because the book was ‘old’ and also because of the humorous way the student had justified using this particular information source. According to the students’ understanding, only books written in the 2000s are usable information in their community.

Student 8: The more recent the [book] better. A lot of students might be told to find newer material if they write something using such an old book.

Researcher: Where do they assume this?

Student 7: That’s what they demand.

Student 8: Right. We’re required to have new material.

Researcher: You mean in the Media Education curriculum or by the teachers in the program?

Student 2: No, I mean the lecturers tell us to.

Researcher: The lecturers? Really?

Student 8: It’s not written down anywhere.

Student 2: The bachelor’s thesis supervisors and others.

Researcher: Right, the bachelor’s thesis supervisors.

Student 1: And the master’s thesis supervisors.

Student 2: On the master’s thesis.

As the stimulated-recall interview proceeded, the students started evaluating information and its sources and age. It seems reasonable to integrate this kind of evaluative discussion into the problem-based learning tutorials. One student mentioned a 1980s book that one of his teachers uses persistently in his teaching. This example evoked a more general discussion about ‘old’ information sources.

Student 1: The things [covered in the ‘old’ books] are still relevant and useful.

Student 3: And somehow it seems like a lot of the older books are in fact more carefully written—better thought-out, with better structure and content.

Researcher. [Clearer] than today’s sort of project-type, quick…quickly produced [publications]?

Student 3: You have pictures all over the place and like…this looks great!…but this is not necessarily something that works in a book.

Conclusions

The research results suggest that problem-based learning supports the collaborative construction and development of information literacy, as defined in this research. The operational procedure of problem-based learning supports the realization of characteristics that are central to the learning of information literacy, that is, student-centredness, students’ active role, small-group work, self-directed learning, experiential learning and the tutor’s role as a facilitator (Barrows 1996; Hmelo-Silver 2004; Poikela & Poikela 2005b). The results indicate that Digital Video course students were in a self-directed and active role with relation to information, knowledge and learning. Determining the extent of information needed, acquiring knowledge and evaluating and using information were collaborative, co-operational and conversational processes. In addition, it seems that information literacy teaching can be integrated into problem-based learning procedures. Interestingly, the results indicate that problem-based learning functioned as a showcase for the collaborative nature of students’ information literacy. The research revealed that students shared conceptions of the age of information with respect to its usability.

On the basis of the results it can also be argued that, to better support students’ information literacy, more information literacy teaching should be integrated into the Digital Video course. The teaching should take place just in time with respect to students’ problem-solving process, and it should focus on issues relevant to the course goals and problems handled during the course. The results of this research confirm previous arguments about the need to integrate problem-based learning and information literacy teaching (Breen & Fallon 2005; Poikela & Poikela 2005a; Rankin 1996).

Evaluative talk focusing on knowledge acquisition, information and its sources was scarce during the course. One possibility for developing the course is to use a course blog during students’ independent knowledge acquisition to make sharing and evaluating of information and its sources possible. Furthermore, the research revealed the need to integrate in the Digital Video course guidance in searching and using research articles in the English language. The results indicate a need to integrate critical media literacy and media proficiency teaching in the course. In practice, this can mean integrating a media-critical analysis (Suoranta 2003) of the digital videos into the learning process.

This chapter presents a fairly optimistic picture of the relationship between problem-based learning and information literacy. We want, therefore, to emphasize some possible limitations that applying problem-based learning may have with respect to students’ information literacy learning. First, we want to emphasize that, although the research results of three decades of problem-based learning have demonstrated that problem-based learning students team to apply their knowledge better, more research on the moderating factors is needed because there a lack of homogeneity across studies (Strobel & van Barneveld 2009; Walker & Leary 2009). Second, in this research problem-based learning was applied to a single course, not at the curriculum level. This can be problematic with respect to pedagogy (Poikela & Poikela 2005a) and with respect to the practical organization of teaching, and it can have a negative effect on students’ learning motivation (Hmelo-Silver 2004). Despite the limitations, this research encouraged students to reflect on their knowledge and information literacy. In addition, the research has, in a positive way, forced the authors to reflect on how problem-based learning can be utilized to promote students’ information literacy.

References

Adams, D., Hamm, M. Media and literacy: Learning in an electronic age: issues, ideas, and teaching strategies. Springfield, Ill: Charles C Thomas; 2000.

Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL), Information literacy competency standards for higher education, 2000. Chicago, III., viewed 5 October 2009,. http://www.ala.org/ala/mgrps/divs/acrl/standards/informationliteracycompetency.cfm

Barrett, T., Understanding problem-based learningBarrett T., Mac Labhrainn I., Fallon I.I., eds. Handbook of enquiry and problem-based learning: Irish case studies and international perspectives. All Ireland Society of Higher Education (AISIIE) & National University of Ireland: Galway, 2005:13–25 viewed 21 May 2009,. http://www.aishe.org/readings/2005-2/chapter2.pdf

Barrows, l.l. How to design a problem-based curriculum for the preclinical years. New York: Springer; 1985.

Barrows, H.S. Problem-based learning in medicine and beyond: A brief overview. In: Wilkerson L., Gijselaers W.H., eds. New directions for teaching and learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1996:3–11.

Breen, E., Fallon, H., Developing student information literacy to support project and problem-based learningBarrett T., Mac Labhrainn I., Fallon H., Barrett T., Mac Labhrainn I., Fallon H., eds. Handbook of enquiry and problem-based learning: Irish case studies and international perspectives. All Ireland Society of Higher Education (AISHE) & National University of Ireland: Galway, 2005:179–188 viewed 21 May 2009,. http://www.aishe.org/readings/2005-2/chapterl7.pdf

Bruce, C. Information literacy research: Dimensions of an emerging collective consciousness. Australian Academic and Research Libraries. 2000; 31(2):91–109.

Cobb, P., Confey, J., diSessa, A., Lehrer, R., Schauble, L. Design experiments in educational research. Educational Researcher. 2003; 32(1):9–13.

Design-Based Research Collective (DBRC). Design-based research: An emerging paradigm for educational inquiry. Educational Researcher. 2003; vol. 32(no. 1):5–8.

Dochy, F., Segers, M., Van den Bossche, P., Gijbeis, D. Effects of problem-based learning: A meta-analysis. Learning and Instruction. 2003; 13(5):533–538.

Erickson, F. Definition and analysis of data from videotape: Some research procedures and their rationales. In: Green J.L., ed. Handbook of complementary methods in education research. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2006:177–191.

Eskola, E.L., Information literacy of medical students studying in the problem-based and traditional curriculum. Information Research. 2005;vol. 10(no. 2). paper 221, viewed 21 May 2009,. http://InformationR.net/ir/10-2/paper221.html

Hakkarainen, P. Designing and implementing a PBL course on educational digital video production: Lessons learned from a design-based research. Educational Technology Research & Development. 2009; 57(2):211–228.

Hakkarainen, P. PBL informaatiolukutaidon yhteisöllisenä tukena ja näkyväksi tekijänä’. In: Sormunen E., Poikela E., eds. Informaatio, informaatiolukutaito ja oppiminen. Tampere: Tampere University Press; 2008:130–160.

Hakkarainen, P., Promoting meaningful learning through the integrated use of digital videosDoctoral dissertation, Acta Universitatis Lapponiensis 121. Rovaniemi, Finland: University of Lapland, Faculty of Education, 2007.

Hakkarainen, P., Designing and producing digital videos as a problem-based learning cycle to support meaningful learningMultisilta J., Haaparanta H., eds. Proceedings of the Workshop on Human Centered Technology HCT06. Tampere University of Technology: Pori, Finland, 2006:4–13 viewed 21 May 2009,. http://amc.pori.tut.fi/hct06/hct06proceedings.pdf

Hakkarainen, P., Saarelainen, T., Ruokamo, H. Assessing teaching and students’ meaningful learning processes in an E-learning course. In: Spratt C., Lajbcygier P., eds. E-learning technologies and evidence-based assessment approaches. New York: IGI Global; 2009:20–37.

Hakkarainen, P., Saarelainen, T., Ruokamo, H., Towards meaningful learning through digital video supported case based teaching. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology. 2007;vol. 23(no. 1):87–109 viewed 21 May 2009. http://www.ascilite.org.au/ajet/ajet23/hakkarainen.html

Hmelo-Silver, C.E. Problem-based learning: What and how do students learn? Educational Psychology Review. 2004; 16(3):235–266.

Kämä, M., Kallioniemi, M. Verkkotyöskentelyn osuus yhteisen tietoperustan rakentamisessa. In: Portimojärvi T., ed. Ongelmaperustaisen oppimisen verkko. Tampere: Tampere University Press; 2006:47–68.

Lietsala, K., Sirkkunen, E., Social media: Introduction to the tools and processes of participatory economy (Hypermedia Laboratory Net Series 17). Tampere University Press, Tampere, 2008. viewed 21 May 2009. http://tampub.uta.fi/haekokoversio.php?id=231

Manninen, J., Burman, A., Koivunen, A., Kuittinen, E., Luukannel, S., Passi, S., Särkkä, H. Environments that support learning: An introduction to the learning environments approach. Vammala: Finnish National Board of Education; 2008.

Marland, P. Stimulated recall from video: Its use in research on the thought processes of classroom participants. In: Zuber-Skcrritt O., ed. Video in higher education. London: Kogan Page; 1984:156–165.

Moust, J.H.C., Van Berkel, H.J.M., Schmidt, H.G. Signs of erosion: Reflections on three decades of problem-based learning at Maastricht University. Higher Education. 2005; 50(4):665–683.

Poikela, E. Ongelmaperustainen oppiminen yliopistossa. In: Poikela E., Öystilä S., eds. Tutkiminen on oppimista: ja oppiminen tutkimista. Tampere: Tampere University Press; 2001:101–117.

Poikela, E. Knowledge, knowing and problem-based learning: Some epistemological and ontological remarks. In: Poikela E., Nummenmaa A.R., eds. Understanding problem-based learning. Tampere: Tampere University Press; 2006:15–31.

Poikela, E., Nummenmaa, R. Ongelmaperustainen oppiminen tiedon ja osaamisen tuottamiscn strategiana. In: Poikela E., ed. Ongelmaperustainen pedagogiikka. Tampere: Tampere University Press; 2004:33–52.

Poikela, E., Poikela, S. Ongelmaperustainen opetussuunnitclma: Teoria, kehittäminen, suunnittelu. In: Poikela E., Poikela S., eds. Ongelmista oppimisen iloa. Ongelmaperustaisen pedagogiikan kokeiluja ja kehittämistä. Tampere: Tampere University Press; 2005:27–52.

Poikela, E., Poikela, S. The strategic points of problem-based learning: Organising curricula and assessment. In: Poikela E., Poikela S., eds. PBL in context: Bridging work and education. Tampere: Tampere University Press; 2005:7–22.

Poikela, E., Poikela, S. Problem-based curriculum: Theory, development and design. In: Poikela E., Nummenmaa A.R., eds. Understanding problem-based learning. Tampere: Tampere University Press; 2006:71–90.

Poikela, S. Ongelmaperustainen pedagogiikka ja tutorin osaaminen. Tampere: Tampere University Press; 2003.

Poikela, S., Portimojärvi, T. Opcttajana vcrkossa. Ongelmaperustainen pedagogiikka verkko-oppimisympäristöjcn toimijoiden haastecna. In: Korhonen V., ed. Verkko-oppiminen ja yliopistopedagogiikka. Tampere: Tampere University Press; 2004:93–112.

Poikela, S., Vuoskoski, P., Kärnä, M. Developing creative learning environments in problem-based learning. In: Oon-Seng Tan, ed. Problem-based learning and creativity. Singapore: Cengage Learning; 2009:67–85.

Rankin, J.A. Problem-based learning and libraries: A survey of the literature. Health Libraries Review. 1996; 13(1):33–42.

Reid, M., Burn, A., Parker, D. Evaluation report of the Becta digital video pilot project. British Film Institute; 2002.

Repo-Kaarento, S. Yhteisöllistä ja yhteistoiminnallista oppimista yliopistoon–käsitteiden tarkastelua ja sovellutustcn kchittelyä. Kasvatus. 2004; 35(5):499–515.

Ruberg, L.F., Moore, D.M., Taylor, C.D. Student participation, interaction, and regulation in a computer-mediated communication environment: A qualitative study. Journal of Educational Computing Research. 1996; 14(3):243–268.

Ruokamo, H. Näkökulmia mediakasvatuksen opetukseen ja tutkimukseen. In: Niikko A., Julkuncn M.-L., Kentz M.-B., eds. Osaamisen jakaminen kasvatustieteessä. Professori Jorma Enkenbergin 60-vuotisjuhlakirja. Jocnsuu: Joensuun yliopisto, kasvatustieteiden tiedekunta; 2005:131–153.

Ruokamo, H., Telia, S. An M+I+T++ research approach to network-based mobile education (NBME) and teaching–studying–learning processes: Towards a global metamodel. Transactions on Advanced Research. 2005; 1(2):3–12.

Savin-Baden, M., Howell Major, C. Foundations of problem-based learning. London: Open University Press; 2004.

Schmidt, H.G. Problem-based learning: Rationale and description. Medical Education. 1983; 17(1):11–16.

Schuck, S., Kearney, M. Capturing learning through student-generated digital video. Australian Educational Computing. 2006; 21(1):15–20.

Shewbridge, W., Berge, Z.L. The role of theory and technology in learning video production: The challenge of change. International Journal on E-learning. 2004; 3(1):31–39.

Street, B., What’s “new” in new literacy studies? Critical approaches to literacy in theory and practice. Current Issues in Comparative Education. 2003;vol. 5(no. 2). viewed 21 May 2009. http://www.tc.columbia.cdu/cice/archives/5.2/52strcct.pdf

Strobel, J., van Barncveld, A. When is PBL more effective: A meta-synthesis of meta-analyses comparing PBL to conventional classrooms. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-based Learning. 2009; 3(1):44–58.

Suoranta, J. Kasvatus mediakulttuurissa. Jyväskylä: Vastapaino; 2003.

Telia, S., Vahtivuori, S., Wager, P., Vuorento, A., Oksanen, U. Opettaja verkossa–verkko opetuksessa. Helsinki: Edita; 2001.

Tuominen, K., Savolainen, R., Talja, S. Information literacy as a sociotechnical practice. Library Quarterly. 2005; 75(3):329–345.

Tynjälä, P. Writing, learning and the development of expertise in higher education. In: Tynjälä P., Mason L., Lonka K., eds. Writing as a learning too: Integrating theory and practice. Dordrecht: Kluwer; 2001:37–56.

Valtanen, J. Ongelma ongelmaperustaisessa oppimisessa. In: Poikela E., Poikela S., eds. Ongelmista oppimisen iloa. Ongelmaperustaisen pedagogiikan kokeiluja ja kehittämistä. Tampere: Tampere University Press; 2005:211–239.

Vesterinen, O., Vahtivuori-Hänninen, S., Oksanen, U., Uusitalo, A., Kynäslahti, H. Mediakasvatus median ja kasvatuksen alueena – deskriptiivisen mediakasvatuksen ja didaktiikan näkökulmia. Kasvatus. 2006; 37(2):148–161.

Walker, A., Leary, H. A problem-based learning meta analysis: Differences across problem types, implementation types, disciplines, and assessment levels. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-based Learning. 2009; 3(1):12–43.

Wang, F., Hannafin, M.J. Design-based research and technology-enhanced learning environments. Educational Technology Research and Development. 2005; 53(4):5–23.