Social media and social capital (with an emphasis on security)

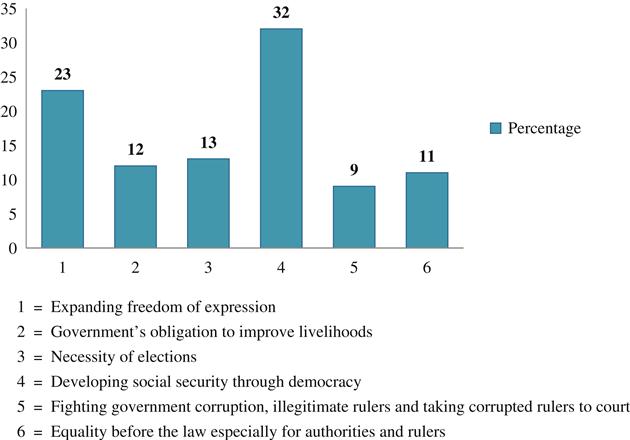

There are several works that highlight the role of the mass media when a unified message is broadcast. The same role for social media has not been proved yet, given the impossibility of propagating identical messages across the social media, as every participant might post a contrasting idea and jeopardise the chance of the main message getting through to every single addressee. Thus no such increase in social capital is expected from social media. On the other hand, this study is not intended to discuss the unilateral role of the media and social capital, but rather it is an attempt to discover what factor, among the sub-factors of social capital (e.g. participation and trust) may attract people to use social media. This chapter also delves into the concept of security and argues that people find social media more appealing when they feel less secure. Another notable finding of this chapter is that one of the top posts made in social media by the opposition in Arabic countries – almost one third of all posts – was ‘improving social security by democracy’.

Keywords

participation; social capital; social security; trust

Security and social capital

Some researchers maintain that social capital means ‘goodwill’ between people and within groups, and includes further sub-categories such as ‘social awareness, self-management, trust, and so on’ (McCallum and O’Connell, 2009). Suppose you live in a society in which you have no power over social life and the government. Such a way of life induces the feeling that a greater power is working to manipulate social life and is trying to strengthen its grip on every aspect. How secure might you feel living in such a society? There is a mutual relationship between the terms ‘security’ and ‘social capital’. A sense of trust grows in a society when the people feel healthy mentally, secure economically and free to make decisions. Moreover, a sense of trust improves security, which in this chapter is considered a prerequisite of social capital. A questionnaire designed by the author was used to evaluate the security of the society in the countries under study. Although other studies used economic factors as the main indicator of the security of a society, this study deals only with:

The role of political factors in social security

This section deals with the role fulfilled by the power of political parties, their freedom, their role in national development, and the intensity of control and supervision of the parties. Indeed, people perceive trust in strong parties as a mediator between themselves and the government. They find parties to be reliable tools through which they can supervise the political affairs of their society. Social security in this regard was evaluated in Egypt and the results showed people were strongly dependent on political parties and found them effective factors in planning their future. The recent revolution in Egypt and relative freedoms afterward resulted in the sudden emergence and multiplication of political parties. On the one hand this gave the people of the country a chance to join at least one party, and on the other seriously violated trust in the parties. In fact, Egyptians trusted only the three political parties from the former regime, rather than the many parties that had recently emerged, a phenomenon that has affected the solidarity of the nation.

This ubiquitous mistrust is evident even in the mass media, so that a surge of posts for or against specific political parties has taken place. This plurality of political parties cannot be found in Libya, Jordan, Yemen and Tunisia. The parties active in these countries are exactly those that would have been active in the pre-revolution era. The Egyptian people have experienced a loss of their sense of belonging, while inter-group trust has grown. This is a serious threat in Egypt, as well as in the other four countries mentioned above, to a lesser extent. In such a situation, people try to show off their own talents instead of emphasising the role of the group. This leads to individualism in society. We must remember that a party is a political unit comprised of a group of citizens, and aims to play a more profound role in the lives of the citizens by defeating other parties. Thus, by building intra-group trust, social capital results in more powerful parties. To be clearer, let’s draw an analogy between political parties and domestic businesses: just as a business with more customers than its competitors outperforms those competitors in term of profitability and social standing, so those parties with more members enjoy more power. Thus political parties adopt marketing approaches with an emphasis on concepts such as social responsibility, an idea known in the business world as corporate social responsibility (CSR). As found in the literature, the social responsibility of businesses is defined as a commitment to dedicate a portion of their income to non-profit and charity works (Lichtenstein, Drumwright, & Braig, 2004). In other words, the basic idea of CSR is to be responsive to the legitimate expectations of stakeholders (Nijhof, de Bruijn, & Honders, 2008). A wide range of customers, citizens, employees and so on constitutes the stakeholders. A notable point that is also of concern in the present text is that people from different cultures and different nationalities have different perceptions of the responsiveness of the multinationals (Endacott, 2003). Therefore, although it is rarely achieved, having an identical influence on all the members of the party (who might be from different countries) is very fruitful. One of the best ways to lure or even trick customers into visiting a firm’s web page is to emphasise popular social responsibility. That is, a better choice of social responsibility is not necessarily one that is of more benefit for the society, but rather the more popular the social responsibility the better. This leads less popular firms to copy the social responsibility strategy of competitors, a phenomenon known as social responsibility mimicry. Other authors believe that the Internet can be a means to collect information on and feedback from the stakeholders (Branco and Rodrigues, 2008). This highlights another aspect of companies’ social responsibility, which indicates that a specific social responsibility strategy can be designed for specific groups of people. To this end, the Internet and social networks are the best means. Following this strategy, political parties try to attract groups of people, who may join the party for reasons very different from those of other members. Suppose a party tries to convey the idea that it will pursue more social freedom for women and more effective child labour laws if the party wins an upcoming election. Clearly, propagating this message in social networks is highly effective in attracting more followers. But the question is whether there is any relationship between the extent of social responsibility and the support received from the social media. The first measure of social capital is ‘group characteristics’ which encompass issues such as the number of members and their participation in decision-making. Group characteristics have a two-sided effect: on the one hand the party tries to attract more members, while on the other hand people tend to join larger groups with more power to influence social matters. Furthermore, it is clear that the higher the number of members in a group, the less the influence held by a single member. However, effectiveness and participation in group decisions, within the realm of social media, are no longer a concern and people only want to be a member of the group, even if they play no role in that group. Social interactions are the fundamental elements of any society. From a network viewpoint, relations and ties are taken as social capital, through which people enjoy accessing the resources and support available in the network. As noted, however, as in physical society, the individual gradually loses their chance to have a say in group decision-making. The most notable issue regarding symbols of technology in Arabic countries is that the Internet, for example, is dealt with as a problem. Consequently, its development and expansion has been problematic and not surprisingly the main functions of the Internet and social media have been introduced into these countries only after a delay of some years. In the early days of the introduction of the Internet into a society, entertainment functions overshadow its other uses. This explains why the positive functions of the Internet, such as higher participation rates and civic engagement, lag behind, although these are per se subject to mediatory factors, such as trusting the websites, the development of communication infrastructures, political development and demographic variables.

Factors in individual decision-making at the national level

Among the different roles of social media as accelerators of revolution in Arabic countries, participation stands out absolutely. Our survey of the four Arabic countries revealed that an increase in public participation was the main factor in the expansion of the media in society and in this regard ‘participation training’ was most effective. Doubtless, social media have a profound effect on increasing/decreasing participation in social issues and social phenomena. They fulfil a leading role by motivating, supporting and informing groups of people and uncovering social matters. Thus social media can lead and organise public participation or grab public attention on a specific social issue – an invitation to participate in or boycott an election is one common example. For instance, the activists and users of social media in Iran were the same in the two presidential elections of 2009 and 2013; however, in the former case they played a destructive role, while in the latter they constructively spread hope nationwide. Although the activists in the social media in Iran played a different role by opposing the presidency of Dr Ahmadi Nejad in 2009 and supporting Dr Rouhani in 2013, they played a notable role in increasing participation and demonstrating the extent of social capital in Iran. Participation, per se, needs ‘knowledge’, which is transferred by training. Therefore, by providing that training, the social media play a notable role in the development of social capital. It is noticeable that such training is not provided as an integrated and organised programme, but instead happens through a wide variety of posts by the users. That is, there is no recognisable body that undertakes training in social media but rather all users play an active role in mutual learning; this learning is based on trust in the wisdom of the crowd. Training by the mass media can be misleading as it can be manipulated by the parties to meet their specific political wills, which is quite different from the general perception of training. Training is the fundamental and vital goal of social activities and development in different fields depends on it. Nowadays, political parties put emphasis on providing training opportunities for the users of social media from different social classes. Attention to and expectations from training are growing in parallel, so that where once it was enough to hold a training course and find enough participants, now parties also expect the training to facilitate their political goals. Thus parties’ training activity in the social media is concerned with both providing the training and ensuring the effectiveness of such training.

Behavioural learning theory (that the individual learns through personal experience) partly explains the learning mechanism; however, it fails to elaborate and justify the whole learning process in its more complicated and wider context. The social learning theory, therefore, states that in addition to direct experience, learning may occur by observing others’ actions and outcomes. In other words, as the theory implies, learning is the outcome of mutual and continuous interactions and influences between the individual and the social environment, and these influences are amplified by the social media. That is, behavioural changes (as a result of learning) depend on:

• whether what is taught is important for the learner;

The answer to all these questions is ‘yes’, given that there is great variety in the subjects of training and individuals can choose what they learn. However, the intention of political parties is not academic training, but rather the manipulation of political training to attract more people. The role of the social media in introducing parties and politicians to the countries studied in this book, which are characterised by social relations based mostly on oral culture, has been to document this oral culture and to improve public awareness, so that liberal thoughts are probably the outstanding feature of this awareness. Political training and the propagation of information by political parties, of course, are in line with the goals and plans of the parties. To gain public support and trust political parties always have to support national interests and goals, while at the same time following their own strategies, especially during elections. To be effective bodies in the political awareness of the public, parties have to acquire the trust of the people. Political parties need to gain public support and in order to do so elaborate and justify their ideologies and programmes.

Transforming public culture into political culture is another function of the social media in Arabic countries. There is a direct relationship between training in political culture and participation in civic society. Not surprisingly, a society which is poor in political culture is more eager to find access to training sources and join social media. A critical element of the political behaviour and actions of people in a society is their political culture, as it may influence people – political actors – by indirectly imposing values and models. On account of the variety of factors in the formation of political culture throughout the ages, including geographical region and political system, studying political culture is not straightforward. It is a function of public culture and this relationship between the two is evident in every society. The difference between political culture and public culture is the former’s focus on the structure and function of power and authority, whether practically or fundamentally. Indeed, the basic rules of implementing policies are determined by political culture, which also dictates the common beliefs and thoughts that constitute the foundations of political life. The different behaviours of nations in the political field can be explained by studying the political cultures of those nations. The functions of any state are based on a social ground making the political culture essential for retaining power and sovereignty; thus the state manipulates the political culture to guarantee its survival. This means that coordination between the political culture and the political system will lead to political stability. In general, political culture consists of political attitudes, knowledge and skills. In fact, by studying people’s attitudes toward the political system we can learn about the political culture of a society. Political culture is a measure of knowledge about power and politics within different social classes. For example, one feature of the political culture in underdeveloped societies – and even in some Arabic countries, such as Jordan and Yemen – is an indifference to political matters, while other countries, such as Egypt, are far more developed in this regard. Indeed, the development of the political culture aided by the social media played a notable role in the outbreak of the recent revolution in Egypt. In the light of this, the authorities in Iran and Saudi Arabia felt it necessary to implement Internet filtering programs to attenuate the role of social media in the public domain. Through such filtering, they tried to stop the development of the political culture, and it is illuminating that this was done under the pretext of religious concerns. Indeed, the authorities have never admitted to the political concerns behind the filtering programs. A notable point regarding the role of social media in the development of political culture is that the mass media in the majority of Middle Eastern countries are state-run. As a result, these media broadcast only pro-government messages, prompting people to turn toward social media to access real information. Government-imposed limitations have resulted in the building of trust in the social media and political parties have made the best use of such trust. The mass media mediate between the people and their environment and usually transfer concepts that have been manipulated, through multilateral interactions, by groups and individuals. On the other hand, instead of mediating, social media are part of the environment and their most outstanding feature is their continuous evolution. At the same time, the extent to which political culture is transferred changes so that the culture can be manipulated by a new power at any moment. The fact is that while powerful media alone are quite capable of triggering big changes in public opinion, their power lies in their ability to empower specific modes of thought so that they create public readiness for change, or they may even go further and steer that change. There are many factors in this readiness, a crisis that attacks public belief in the ruling system. When this happens, individuals with weaker group ties tend to be more open to hear what the opposition has to say. Thus it is not surprising to see a surge of desire for change when social stability and group solidarity (social capital) begin to decline. When this happens, the mass media have more power to trigger new ideas in the society, or at least a popular character can grab the opportunity and reach out to the public. Indeed, the infusion of information by the social media is so immense that people in contact with these media are inevitability informed about developments and share their findings with others. All these trends and factors, although ambiguous and intangible, influence our behaviour, although the trend is so slow and so shallow that it cannot be taken as direct suggestion. For instance, in some developing countries, including Iran and other Arabic countries, state TV and radio channels, intentionally or unintentionally, follow the Western style of propagating a culture of consumption and in general advertise a life of routine, stagnated social structure and underdevelopment. These policies, somehow, pave the way for a cultural invasion. In fact many policy-makers in third-world countries, whether intentionally or not, have adopted Western attitudes and propagate Western social institutions and values, regardless of their native cultures. In addition, as mentioned above, people in these countries are deeply influenced by this trend even though they do not trust the state media. Bearing this in mind, imagine how effective the social media can be in influencing the public culture, given the trust people have in these media. A comparison was conducted between the level of public trust in mass and social media (Figure 3.1).

As Figure 3.1 shows, there is a notable difference between the levels of trust in the mass media and in the social media in Arabic countries, which is not comparable with that in the USA. The fact that many of the mass media in the USA are run by the private sector, whereas the government controls the mass media in Arabic countries, is one of the reasons for this difference. It is noticeable that extended control by the state of the mass media and censorship imposed on the news lead many to look for accurate and complete news items in the social media. The media relies on public trust for survival and thus it is not surprising that many mass media organisations in Arabic countries do not survive long. Therefore the rebuilding of public trust is one of the first priorities of state-run media in these countries.

Factors in participation in the security of society

Although the security of society is one of the tasks of government, it is not achievable without public participation. Such participation is crucial for establishing social security and specific methods must be adopted to internalise it. A key factor in participation is awareness, as nationalistic attitudes grow when people are informed about national issues. An individual cannot be expected to be interested in a matter of which they do not have any knowledge. Threats and risky situations, even if not based on solid facts, induce awareness. All living creatures naturally tend to react to threats. Lack of security in a society is an immense threat, which is sometimes neglected by the people owing to lack of awareness of the problem, which in turn presents another threat to the society. Awareness of threats and dangers can also be approached from a psychological point of view, addressing how to inform people about the lack of security. For instance, the social media in Iran have introduced a destructive phenomenon that threatens the security of the society. Now the question is: how can people accept the social media as a threat when they do not trust the source that propagates that idea? Thus the loss of trust in one type of media and the build-up of trust in another changes participation in social security, as people do not trust the media that call for public participation. Islam, in the countries under study, is a key player. The Islamic order ‘to enjoin good and prohibit evil’ resembles active public participation in the society, which is called by sociologists ‘social capital’. Reduction of social capital and public participation leave no other way for the government but to rely more on force. The mere utilisation of force makes many of those who are needed to actualise and implement the force leave the body of government, which in turn leads to the hard-line approach to security, putting more emphasis on threat. Moreover, as the government does not enjoy public support, approaches to security take over social dynamics and the main portion of expenditure.

The most basic pro-participation belief is an acknowledgement of the equality of citizens. The purpose is to improve cooperation, sharing and sympathy among individuals, which leads to a qualitative and quantitative improvement in life in economic, social and political fields. Participation is a process that people use to initiate change in their environment and themselves. These changes are frequently emphasised by Islam. Social participation necessarily needs the proper ground in which to evolve. Development of such proper ground depends on the empowerment of civic society, institutions and pertinent processes. In principle, the development of civic society entails the institutionalisation of common bodies and real public participation, in turn, leads to the empowerment of civic society. Features such as volunteerism, awareness and the desire to participate connect participation to civic society. Volunteer associations prepare individuals for social participation. Civic institutes include guild unions, political parties, private business groups, cooperatives, art associations, newspapers, charity organisations and even neighbourhood gatherings. Social media highlight the voluntary bases of these activities as no one can prohibit or dictate membership of a virtual association.

Therefore, as frequently emphasised by Islam, trust and participation are two key elements of social capital and, in this regard, the social media amplify participation. It is notable that God and fate are two undeniable factors in people’s lives in the Arab countries of the Middle East and Iran and overshadow the notion of the individual will. While social media do not tackle this belief, they induce the idea that people can play a determining role in their lives. The social media do this by introducing man’s will as a part of God’s will in determining the fate of society and the people. In this way, improving self-belief is the smallest role played by social media in Arabic countries.

Actual extent of the rule of law

As the survey results revealed, there is a correlation between the actual extent of the rule of law and the two variables of social capital, trust and volunteerism. The greater the rule of law, the more interested people are in helping others, which in turn results in the growth of trust. Our results showed that for Arab people the actual rule of law is measured by two key factors:

• total number of people in society who are treated equally by the law;

• participation of people in legislation through free elections.

There is a wide gap between the gravity of these factors for the people and the actual status of society regarding these factors in the Arab countries. The interesting point is that the surveys were carried out after the revolutions and people were still dissatisfied regarding these two factors. The widest gap was observed in Egypt, with many Egyptians believing that the new constitution would actually increase injustice in society and grant more power to Mohammad Morsi. The fact that, under the new law, the authorities were granted immunity of jurisdiction was interpreted as an expansion of injustice in society. In the absence of social media, lack of social power leads to a sort of political strangulation in society, which gradually limits the power of the rule of law over the government. The social power of the people in Arabic countries re-emerged within the frame of virtual media after the introduction of social media, which enabled the flow of transparent information and criticism of the government’s actions. The inequality of people before the law is not limited to discrimination against or in favour of some officials and authorities, but can be traced even to relatively small issues such as prohibiting women from driving cars in Saudi Arabia. Discrimination against women in Saudi Arabia has inspired several anti-government campaigns on Facebook which, like any critic of the government, has triggered worries among the leaders of the country. As mentioned in Chapter 1, along with the increasing participation in the elections of 2009 in Iran, social media have played a notable role in spreading the idea that election results could be manipulated. In this case, people found their right to decide their own future was in jeopardy. Participation in the legislative process is the dominant demonstration of people’s sovereignty and right to determine their own political and social fate. People, nowadays, implement this right indirectly and through their representatives in parliament. However, the role that people can play in social media, i.e. supervision, is more crucial. Figure 3.1 demonstrates that lack of trust in the mass media is more evident than trust in the social media. Another way to approach this is to ask if there are any differences between participants in the social media and non-participants with regard to the level of social trust. In view of the problems in studying non-members in Arab countries, the first part of the study was limited to Iran. Interestingly, the results showed that no significant differences can be supported regarding these two groups. However, the participants in the two groups agreed on the fact that lack of trust in society, lack of knowledge of people’s rights and social problems at the macro level, such as poverty, can be considerably effective in attracting more people to social media as a way to claim their legitimate rights.

In conclusion, the results of a study based on a theme analysis of 1,434 randomly selected tweets from five countries in 2013 are presented in Figure 3.2 (note that private messages, images and irrelevant tweets were removed from the analyses). Evidently cases ‘4’ and ‘6’ are highly pertinent to social security and social capital, topics covered in this chapter. Tweets (i.e. participation) in these two fields comprised 43 per cent of the tweets analysed in the study.