CHAPTER 3

Accountability for Results

IMAGINE YOURSELF AT a basketball game. There you are seated front-row center when the players take the court. The teams are composed of ten of the finest athletes in the world, and this is championship play. The buzzer sounds, the ball is in the air, and these million-dollar giants take over. The arena is packed, and ten thousand hearts beat as one as twenty thousand eyes follow the ball. Suddenly, a grunt, a flash, and a man is borne into the air. A ball is plunged through a hoop, a glass backboard shatters, and all hell breaks loose. Amidst the hoopla, you glance up to see the score.

But there is no scoreboard! There is nothing but thin air where a scoreboard should be. Suddenly all that was held so closely just seconds before is lost. Despite the wizardry of the athletes and the magic of the moment, the game is nothing without the score.

How many of us have, at one time or another, worked for a manager or project leader who did not keep score? Managers who: 1) could not communicate clear performance expectations; 2) routinely played favorites by holding some team members to one standard and other team members to a different one; 3) offered us no way of tracking or assessing our performance; and 4) evaluated our performance on the project in vague or inconsistent ways?

We suspect that practically every reader will answer “yes” to at least one of the above questions. Few things are more disgruntling in the organizational setting than managers who are incapable of effective accountability. One of the critical behaviors that all effective leaders seem to have in common is their ability to demand high performance expectations and clearly communicate those expectations, while holding all subordinates accountable to the same standards of behavior.

Part of effective leadership is rewarding superior efforts and sanctioning those who shirk. At the front end of many projects, leaders will spit bile and pound their chests as though they were silverback gorillas seeking a mate. Yet, come to assessment time and they morph into scampering, tittering rhesus monkeys. The effective leader is one who is adept in granting rewards and sanctions; neither should be excessive. Consistency and fairness in rewards and sanctions build trust and commitment. This is easier said than done; thus, it is helpful to review the process and components of effective versus ineffective accountability systems.

The concept of effective accountability is especially important in project management. Given the constraints of limited time and personnel, this is potentially a teambuster, especially so if the home functional units are still part of the accountability system. For team players who feel that they have been cheated, their reactions can be fatal. They may actively rebel, reduce their efforts, sabotage the project, or just take their ball and go home.

Accountability, a system of comparing the results achieved by the individual or team to some defined expectation, is not a human-resource function. Linking effort and results to consequences is an integral part, not an afterthought, of leadership. The result of this comparison provides a basis for initiating action to reward the superior performer, and sanctioning those who shirk their duties. This chapter provides a brief overview of project leadership processes used to create and, more importantly, ensure such accountability for results. These will be summarized in a generic process model of accountability. We believe that several essential features of any effective accountability system can be derived from an application of this generic model to specific project situations.

FUNCTIONAL ACCOUNTABILITY

Accountability can be harmful as well as helpful. Any level of accountability can be imposed by the leader, due to the leader's formal authority over the project, but not all levels are functional. A level that is too high will cause the team to withdraw from the project; motivation will fall, distrust will develop, and commitment will fall. This occurs because the team is being sanctioned for low performance, which is caused by factors beyond its control. Resentment will ultimately develop. Alternatively, high performers are being rewarded for performance, which, again, is caused by factors beyond the team's control. When this is observed by others, it will be viewed as favoritism, and the high performer may be ostracized. Again, resentment will ultimately develop.

If accountability is too low, motivation will fall as well; good performance is not being recognized, and poor performers are not being corrected. The high performers will observe that there is no penalty imposed on the poor performers, and this, combined with a lack of recognition for their good performance, will cause them to reduce their level of effort to maintain what they perceive to be equity between the work put into the project and the rewards received.

To help illustrate positive from negative accountability structures, we will define the level of accountability in a given situation as the accountability gap, then show how different variables produce levels of accountability that are dysfunctional.

ACCOUNTABILITY GAP

Accountability for performance can be described as the range of performance that goes unrewarded and unsanctioned. That is, accountability is defined by an upper and lower boundary: the closer together these target performance levels are, the higher the level of accountability.

For example, compensation based on commission sales would be considered a high-accountability performance structure: for every sale, the salesperson receives an additional reward (commission), and, for every sale lost, the paycheck is reduced. Since there is no range of performance that goes unrewarded, or sanctioned, accountability is high. Conversely, when there are no levels of performance that earn additional rewards or sanctions, the position has low accountability. For example, a person on salary receives a fixed amount regardless of the actual level of performance. Thus, the accountability gap is wide, and the level of accountability is low.

There are four major features of an accountability system that determine the level of functional accountability: clearly communicating expectations, valid measurement of performance, local control over performance, and timely feedback for corrective action.

COMMUNICATING EXPECTATIONS

That leaders should be effective communicators is common knowledge, but the reasons why are typically less well known. One reason involves accountability. For accountability to be functional, the leader must clearly communicate expectations of performance and consequences of performance. This solves several problems. First, setting goals has been found to have positive motivating effects on subsequent performance. This is especially true when the goals are specific and difficult, yet achievable. When goals are specific, it provides clear direction for effort and increases the team's ability to monitor its progress and stay on track. When goals are difficult, there is a greater sense of pride and satisfaction in successful performance. When the goals are achievable, motivation is high because the team perceives that the accountability system will reward its performance.

Second, the leader must clearly identify the consequences of performance in order to create a sense of equity and motivation. If a reward is announced after successful performance, then two problems develop: 1) The leader has missed an opportunity to use the reward as a motivating mechanism, and, if the idea behind the surprise reward was to create motivation for future projects, then it is wasteful because individuals tend to downplay the desirability of rewards that are not carved in stone; and 2) If other teams are involved, which did not receive equal surprise rewards, then they will suspect favoritism by the leader, and resentment and distrust can develop.

Accountability, then, is limited by the extent to which the leader effectively communicates performance expectations and consequences. That is, functional accountability can only be high when expectations are clearly communicated and understood. This is best achieved when expectations are written. When expectations are in writing, the team has greater confidence that the expectations will not be changed during the project without its knowledge. Unfortunately, it is time consuming, expensive, and difficult to communicate well in writing, especially given that projects often entail many dynamics and unknowns, which are difficult to anticipate prior to the execution of the project. For these reasons, it is common for leaders to communicate expectations verbally and to keep the expectations general and vague, rather than specific. While this may be appropriate, given time and uncertainty factors, it means that high accountability should not be enforced. Thus, the effective leader accommodates this limitation in communicating expectations by widening the gap between performance, which is rewarded and sanctioned. In other words, when we are purposely vague in communicating our expectations, it is important not to be too critically evaluative in sanctioning someone for small differences between their performance and our expectations. Setting the accountability limits/boundaries should be a participative decision. (See the Vroom-Jago Model in Figure 4, for a means of optimizing participation given the situation.) By allowing the team to have input in the accountability process, members will have greater commitment to the project.

Further, it is important that the leader communicate the relevance of the expectations to the needs of the project and organization, as well as demonstrate an awareness of the needs and abilities of the team (as discussed in detail in Chapter 2). That is, the effective leader must do a great deal of homework to determine the needs and constraints of the project, the organization, and the team prior to communicating expectations. Thus, one basic building block of an effective system of accountability is the degree to which project and organizational objectives are explicitly translated into specific operational goals and then effectively communicated to the team.

MEASURING PERFORMANCE

Accountability is only as effective as the performance assessment is valid. When holding the project team accountable for its performance, the leader must take into consideration the accuracy of the performance assessment. If the performance measure is incorrect, the team will be rewarded, or sanctioned, inappropriately. If high accountability is imposed, using an invalid measure of the team's performance, the team will experience high levels of stress. Consequently, the quality of work-life is reduced, and the team's motivation to successfully complete the project is likely to suffer dramatically. To accommodate inaccuracies in the measurement system, the accountability gap is widened. Thus, it is important for the leader to understand the limitations of the performance measure. Measurement error is due to problems of reliability, bias, precision, and relevance.

Measurement Reliability

The problem of reliability involves the extent to which repeated measures of the same item (i.e., performance characteristic) produce exactly the same measurement values. For example, if you step on the bathroom scale, and it reads 185 pounds, and then you immediately step on the scale again, and it reads 188, the next time 184, and so on, the scale is unreliable. To overcome this problem, you could weigh yourself many times and calculate the average. This will closely approximate the true weight if the errors are distributed normally. Thus, the leader should assess the extent to which the performance measure to be adopted is reliable and, if it is not, consider taking repeated measurements in order to calculate the average to be able to approximate the true score.

Measurement Bias

The problem of bias involves the extent to which repeated measures of the same item are incorrect by the same amount, in the same direction. For example, if your true weight is 186 pounds, yet repeated measurements on the scale indicate 188 pounds, then the scale is biased: the error is consistent at plus two pounds. Another example is discrimination, as when a project team leader consistently assesses the performance of men higher than that of women. Clearly then, this is a significant threat to effective accountability and project management. Fundamentally, this is a problem of calibration. To overcome this problem, the leader should measure performance, which can be independently verified. If the leader's measurement is consistently different from the independent measurement, and the error is in the same direction, the bias is readily determined. Unfortunately, this is a particularly difficult problem for project leaders, given that many performance measures have no basis for independent verification. The team is likely to comment on this problem when it is perceived. Thus, it is important for the leader to be sensitive to feedback from the team, which indicates that bias is present in the performance measure, and enlarge the accountability gap to accommodate the error while the source of the error is found and corrected.

Measurement Precision

The problem of precision involves the interpretation limits of the scale of measurement. For example, if the scale of measurement is simply good or poor, we should not rank-order three teams with a rating of good, because there is no measurement basis for distinguishing between relative performance within the category. If ranking performance is necessary, the precision of the measure must be increased. This is a problem of imprecision. Conversely, a measure can be overly precise. Consider, for example, measuring the average number of children in a household for a community; typically, the calculated value is something like 2.5743291. This is a very precise measure, but it cannot be correct for any given house since it would require the existence of a fraction of a child. A value of three would be less precise but more valid. Because higher precision is typically achieved at a greater cost to the project, the leader should adopt a scale of measurement with precision that is no greater than necessary for the circumstances. In general, however, the greater the precision of measurement, the higher the level of accountability that can be achieved.

Measurement Relevance

The problem of relevance involves the extent to which the measure captures the intended aspect of performance. Often, the area of performance to be measured is multidimensional and precludes the use of a single measure, or it is abstract and cannot be measured directly. For example, a team's performance expectation is to arrive at work by 8:00 A.M. and leave no later than 5:00 P.M. This expectation is clearly communicated and understood by the team. A time clock is used to measure actual performance, and this measure is valid: the clock is reliable (it keeps time properly), and it is not biased (it has been calibrated, set to the correct time). Further, the time clock records time to the nearest second, which is sufficient precision to determine whether or not a team member is in compliance with expectations. So far, the accountability system will justify a small accountability gap, and therefore a high level of accountability. However, this performance measure does not indicate the type or amount of work actually completed on the project. Thus, the leader and the team may experience dissatisfaction with this accountability system. This dissatisfaction is likely because the aspect of performance held accountable does not capture the quality of the work and offers little meaningful feedback with which to improve the project. Thus, it is important for the project leader to assess and clearly explain the relevance of performance measures to the team or structure team participation in the decision-making process of selection.

CONTROL OVER RESULTS

Accountability systems only work when the team has control over the results. Rewarding and sanctioning serve no purpose if the outcomes are beyond the control of the team. Quite the contrary, holding the team accountable for performance that is beyond its control will produce stress and withdrawal. Thus, the effective leader designs the project in a manner that maximizes the team's control over results. This is achieved by developing knowledge and skills though training, matching team members’ abilities to project tasks, and structuring the project to accommodate unforeseeable events.

Knowledge and Skill

The project leader should not expect performance from team members who lack the knowledge required to complete the task successfully. Even if the team member has the knowledge, there may exist a lack of experience, which makes the individual perform more slowly or inefficiently. Thus, it is important that the project leader adjust the accountability gap to account for the current level of knowledge and skill. This, of course, will change over time as both knowledge and skill are developed with training and experience. Therefore, the accountability gap should adjust over time, as well, to reflect the stage of development for each team member. That is, the accountability gap should be initially wide to accommodate the team members’ struggle to adjust to the new project task structure and environment. As the team members learn and adapt to the situation, the accountability gap should narrow. As mentioned previously, changes in the accountability gap should include the participation of the team members to ensure feelings of equity and to build commitment and trust. The type and extent of participation by the team in the decision process should depend on the situation (see the Vroom-Jago Model discussion in Chapter 2).

External Influences

Most projects involve significant uncertainties and dynamic complexities, which cannot be eliminated from the project completely; thus, the degree of control achieved by the team is seldom complete, nor is it zero. Accordingly, the project leader should not hold the team accountable for performance that results from unpredictable external events. To maximize accountability, the leader should structure the project to minimize the influence of the external events. This may be achieved through buffering, leveling, rationing, and delegating.

Buffering. Buffering project performance from external events typically involves structuring slack resources into the project. For example, if a task requires eight days to complete, the schedule might be structured to allow ten days. Accordingly, a higher level of accountability can be imposed on performance.

Leveling. Unforeseen events can result in greater demands on a team than anticipated in the project plan. If this causes the team to rush its work to keep up, a low-quality output is expected. Thus, it is the job of the leader to structure flexibility into the schedule, to smooth out or level the demands placed on the team, so that it can perform efficiently and effectively. By leveling the demands on the team, a higher level of accountability can be successfully achieved.

Rationing. External events can cause the requirements of the project to increase. When this change overwhelms the buffering and leveling options available, the project leader must make the difficult decision of how to scale back the size or scope of the project to meet the resources and capabilities of the team. If this is not possible, the leader must ration the team's efforts on the various aspects of the project. This rationing will change the performance expected of the team, and the leader should adjust the accountability gap to accommodate the new requirements on the team. Thus, rationing should be avoided and used only when buffering and leveling are insufficient to accommodate the external impacts on the team's performance.

Delegating. Often, external changes can be accommodated immediately by the team members if they have the authority to adjust the structure of their tasks. This authority must be clearly delegated by the project leader in order to instill confidence and trust. This is a delicate problem because if too much control over the tasks is delegated, then coordination of effort between team members is destroyed. Thus, the leader should delegate as much control over the work as possible, up to the point when changes made by one team member will materially affect the performance of another. Thus, when delegating, the project leader must establish clear boundaries, or set fences, around the domain within which the team members may freely make changes. In general, the greater the authority delegated to the team, the greater the control the team has over its performance, the greater the environmental events that can be accommodated, and, thus, the greater the level of accountability that can be achieved.

Output versus Behavior Control

When external events have a large effect on the team's level of control over project outcomes, or when the outcomes are abstract and difficult to measure with satisfactory validity, the project leader has the option of switching from outcome-based performance to behavior-based performance. In this case, the accountability system is based on expectations and measures of team behaviors, which cause the outcomes. The idea is that the team has more control over its behavior than it has over the consequences of that behavior. This is the better option when there exists a proven, optimal way of conducting the work. The disadvantage of behavior-based accountability systems is the lack of flexibility and discretion available to the team members in conducting their work. This lack of autonomy can reduce the internal satisfaction that the team members experience on the project, resulting in a lower level of motivation. Further, since outcomes are not part of the accountability system, it is more difficult to keep the project on the timeline. Overall, then, the project leader may consider using a combination of outcome-based and behavior-based performance measures to exploit the benefits of each.

Identifiability

A final issue concerns identifiability and shared responsibility. Accountability systems are only appropriate when the team, or team member, is clearly identified with the performance. When individual contribution to performance is clearly identifiable, then accountability at the individual level is appropriate and effective. However, tasks may require the interdependent contributions of several individuals. In this case, individual contribution is difficult to distinguish from the group's performance. In such a case, accountability at the individual level is destructive since rewards and sanctions are driven by performance of other team members, which is beyond the control of the individual member. Accountability can be achieved, however, by measuring the performance of the group, or team, rather than of the individual. That is, as a group, the team has control over its performance, so accountability at that level is functional. In general, as identifiability with performance increases, higher accountability can be achieved.

FEEDBACK AND REACTION TO RESULTS

Having established and communicated expectations to the team, having structured the work to maximize the team's control over its performance, and having established and taken measures of team performance, accountability then becomes a function of comparing actual results to the expectations. The result of this comparison process is the determination of whether the team's performance meets or exceeds the expectations. This is the basis of feedback to the project leader and the team. While it is important that the leader conduct the comparison process to invoke the accountability system, it is also helpful to provide the team with the capability to measure its own performance so that it can conduct the comparison and generate the feedback for itself. This self-management allows the team to make adjustments without the intervention of the leader in order to meet and exceed expectations. (This assumes that the project leader has delegated authority to make changes). This reduces the demands on the project leader, and the autonomy afforded the team can increase members’ intrinsic satisfaction from the work, resulting in increased motivation and improved performance. The tradeoff is the lack of accountability; the leader is not rewarding or sanctioning. Thus, it is always necessary for the project leader to periodically compare actual performance to expectations and provide feedback to the team.

The frequency of the feedback process has a large impact on the effectiveness of the accountability system. In general, the higher the frequency of the comparison process, the better the feedback to the team. That is, the leader and the team can only make informed decisions on how to proceed when feedback is available. The higher the frequency, the greater the number of opportunities to make changes and check the results of previous changes. It is also true, however, that the higher the frequency, the higher the cost of the accountability system. Each comparison process consumes time and resources.

To optimize the tradeoff between the benefits and costs of generating feedback, the project leader should assess the dynamics of the project environment in terms of how quickly the team's performance can break the accountability boundaries. Highly dynamic environments justify the costs of frequent feedback because the team has a greater number of opportunities to make changes. Conversely, frequent feedback in stable environments can be considered an annoyance by the team, as the comparison process will not provide information that is substantial enough to justify taking time to absorb it. This is sometimes referred to as micro-management. This can be avoided by reducing the frequency and by providing the means of self-management feedback, as discussed above, which allows the team to absorb feedback at its own pace.

If the results consistently fail to meet expectations, some form of corrective action needs to be considered. Before taking action, however, the organization must first consider whether the expectations should be changed because they are unrealistically high, or whether there are environmental constraints on the entity that preclude the team from being able to achieve the current expectations. If neither of these is responsible for the lack of results, then corrective action must be implemented.

Corrective Action

A corrective action is any event that produces a change in performance. The resulting change in results is limited by the degree to which the project leader and the team have control over performance. Further, because tradeoffs exist, changes may improve some aspects of performance and reduce others. To document the success of the change, the results should be remeasured in a subsequent period. The frequency of measurement should temporarily increase until an appropriate corrective action is found and performance is determined to meet expectations.

Corrective action is initiated by the detection of a discrepancy between the desired and actual state of performance, as discussed above, but this discrepancy is driven fundamentally by a lack of knowledge or lack of motivation. The accountability boundaries address the latter; the accountability gap accommodates the former.

When performance falls short of expectations, it may be the result of a lack of knowledge of the internal processes (abilities, resources required, and so on) or external events or both. That is, projects are seldom conducted under conditions of complete certainty. As such, progress on these projects is made via conjectures and refutations or trial and error: the team tries an approach and absorbs the feedback as either a rejection of that approach or a confirmation. Indeed, the success of one of America's most famous and formidable projects, The Manhattan Project (the building of the atomic bomb), was attributed to trial and error by physicist John Wheeler, who stated: “The whole idea was to make mistakes as fast as possible.”

The accountability system is not intended to react to feedback generated as a means of acquiring knowledge. This is why the accountability gap exists. A certain range of performance variation is functional in that it allows the team to learn and take risks without fear of reprisal. However, past a certain point, it becomes clear that poor performance is due to a lack of effort, or shirking, and accountability must be invoked. Failure to hold such performance accountable will produce feelings of inequity in the team members who are not shirking. Correspondingly, superior performance should be acknowledged, as well, to maintain feelings of equity in that superior effort will be rewarded.

A PROCESS MODEL OF ACCOUNTABILITY

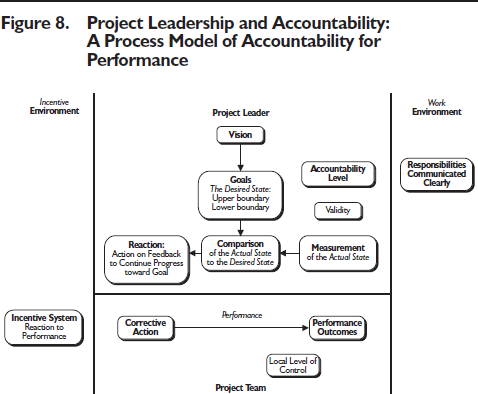

The model presented in Figure 8 summarizes and illustrates the relationships that have been highlighted in this overview. As summarized in the model, the project leader's ability to enhance desired results can be facilitated by:

- explicitly defining and communicating expectations

- increasing the validity of the measures used to evaluate performance

- increasing the team's control over its performance

- providing meaningful incentives for motivating high performance

- adjusting the frequency of measuring and evaluating results to fit the dynamics of the situation

- providing timely and specific feedback to the team about its results

- initiating corrective action based on the feedback.

As each of these factors is improved, the accountability gap may be narrowed, increasing the level of accountability for that aspect of performance, which maximizes both performance and the satisfaction experienced by the team. When these accountability factors can no longer be improved, it is the task of the leader to assess the situation and adjust the accountability gap to accommodate lack of control, measurement problems, unclear expectations, and infrequent or poor quality feedback. Structuring participation and self-management into the accountability system will help to optimize its effectiveness.