CHAPTER 1

Where Are the Fish?

The New Competitive Reality

AT A GLANCE

FOR MOST OF THE history of modern business, we have enjoyed falling prices on nearly all raw materials, which has made us dangerously oblivious to the shaky foundations of our global market economy But the tides are turning: the new era is upon us It is time to look into the facts—and to prepare a strategy for dealing with them.

Like his father and grandfather before him, Al Cattone has been living off the sea for all his life. For the Gloucester fisherman who spent over 30 years braving the Atlantic’s waters, fishing is “not so much a job as it is an identity.”1 But this legacy is coming to abrupt end. In light of extreme declines of cod stocks, the New England Fishery Management Council voted to slash cod catch rates by 77 percent in the area from Cape Cod to Nova Scotia. The destruction of fishing communities across the region is expected to follow, with a domino effect on seafood processors, wholesalers, distributors, and retailers—an entire industrial ecosystem. But the unpopular move is backed by the harsh reality that the cod stocks today are very far from healthy, with some communities netting a bare 7 percent of moderate targets set by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

In his struggle and sadness, Al is not alone. In the United Kingdom, the modern fishing fleet must work 17 times harder for the same catch as its sail-powered 1880s counterparts.2 In northern Japan, the entire fishing industry has been in “terminal decline,” with the 2011 tsunami only accelerating the collapse.3 Recently, the Financial Times has become one of the most prominent voices about the fish crisis, warning the world of the decline in fish stocks, which is more severe than predicted. “More than half of fisheries worldwide face shrinking stocks, with most of these in worse condition than previously thought, leading to yearly economic losses of $50bln.”4 And if the proven losses of the present are not enough, the projected losses of the future exceed anything that could be imagined. According to a Stanford University study, overfishing could take all wild seafood off our tables by 2048. “Unless we fundamentally change the way we manage all the oceans’ species together, as a working ecosystem, then this century is the last century of wild seafood,” warns marine biologist Stephen Palumbi.5

In its easy math and empty-plates impact, the story of fish serves as a perfect metaphor for the entire world of resources our economy is built on. Whether it is fish or oil, clean water or gold, vitamin C or helium, the ocean of resources is running dry, and this is creating havoc in the market worldwide. Not one, not two, but three oceans are getting overextended: the ocean of resources, the ocean of waste, and the ocean of ideas. Here is how.

The Ocean of Resources

The question of declining resources is not new. Long before current frameworks, such as the Natural Step,6 put declining resources at the center of attention, the issue of resource scarcity commanded the notice of theorists and practitioners alike. From Plato7 in the fourth century BC to Thomas Malthus8 in 1798 to the Club of Rome in 1972, a parade of esteemed thinkers drew our attention to the looming collapse—to no avail. Hardly any changes in the behavior of businesses, governments, and consumers alike were inspired by their powerful outcry—if anything, the global market grew tired and deaf to the calls for radically new business models. Why?

While the theory of resource decline seemed strong and sound, for nearly two centuries the market reality had been telling the opposite story. McKinsey’s 2011 report Resource Revolution puts it best:

Throughout the 20th century, resource prices declined in real terms or, in the case of energy, were flat overall despite periodic supply shocks and volatility. The real price of MGI’s index of the most important commodities fell by almost half. This decline is startling and impressive when we consider that, during this 100-year period, the global population quadrupled and global GDP increased by roughly 20 times. The result was strong increases in demand for resources of 600 to 2,000 percent, depending on the resource.9

In essence, what the declining prices of resources told us for so long was that we could have our cake and eat it too—grow our population, increase our consumption, and keep cutting prices, all at the same time.

But that was then.

![]()

The now looks drastically different—and the speed of waking up to this new reality will determine who will survive and who will vanish in the new era. Each year, I work with about 5,000 senior managers directly, and our conversations so far suggest that the majority have not yet fully awakened to this new world of a rapidly collapsing resource base. So here are a few alarm sirens for you—the general trends that are beyond striking:10

• Since the turn of the 21st century, real commodity prices increased 147 percent.

• At a minimum, an additional $1 trillion annual investment in the resource system is necessary to meet future resource demands.

• Three billion more middle-class consumers are expected to be in the global economy by 2030, all putting new pressures on resource demand.

The particularities are no less alarming. Whatever key aspect of business—or life—we consider, declining resources are unraveling the very foundation on which we built our economy.

![]()

For decades, the energy debate has been struggling with the question of how much oil and other fossil fuel is left, with no agreement in sight. What we do have agreement on are the demand and the cost of energy. By 2030, world energy use is expected to exceed the 2011 baseline by 36 percent,11 and the past decade has seen a 100 percent increase in the average cost to bring a new oil well on line. The demand and the supply pressures together create a perfect storm for any business—not because we are running out of oil or any other resource but because the price of energy is becoming severely unpredictable.

THE STONE AGE didn’t end because we ran out of stones.

SHEIK AHMED ZAKI YAMANI

FORMER OIL MINISTER, SAUDI ARABIA

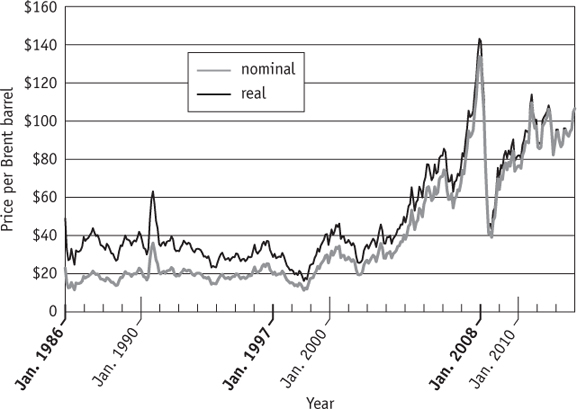

Figure 1 is a simple visualization of this volatility: using nominal data from the Energy Information Administration on spot prices of a Brent barrel of petroleum, converted to US dollars in August 2013 using the US Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPIU) to show a more realistic picture, I have plotted the price of oil from January 1986 to August 2013. It turned out to be a rather exciting roller-coaster ride!

Imagine that we run a company producing chairs—perhaps the very chair you are now sitting on. Much of the raw materials in the chair are petroleum derived or petroleum dependent. Now, imagine that we are trying to set a sound pricing policy for our beautiful chair—and naturally, we need a somewhat stable cost structure. How do you manage the up-and-down movement in the price of oil—and all dependent products—like what we have seen in the last five years?12

Figure 1. Volatility in Brent crude oil prices from January 1986 to August 2013.

If oil prices seem remote to you, the next group of resources cannot possibly leave you uninterested. Do you know anybody who doesn’t eat?

ASK NOT WHAT YOU can do for your country Ask what’s for lunch.

ORSON WELLES

ACTOR AND DIRECTOR

Whenever one talks about food, it is assumed that availability is an issue. Yet when 40 percent of food in the United States is never eaten—amounting to $165 billion a year in waste13—clearly, when it comes to the developed world, availability is not an issue. Instead, accessibility of food is becoming a strategic concern. Like a nice risotto or rice pudding? Of the top 10 rice-producing countries of the world, the first two—China and India—produce and control more than the other eight combined.14 If your company or your supplier depends on rice production, such dependency creates real strategic concern, as exemplified by the story of the 2008 global rice crisis. The crisis took place in early 2008, when the international trading price of rice jumped dramatically, increasing more than 300 percent, from $300 to $1,200 per ton, in just four months.15

Perhaps rice is not your food of choice, and access to India’s resources is far from your business challenges. Yet the global decline of food resources touches every person and every company, if we look at the level of the nutritional content of our most precious vegetable crops. A 2004 study shows an average decline of 20 percent of vita-min C, 6 percent of protein, 16 percent of calcium, 9 percent of phosphorus, 15 percent of iron, and 38 percent of riboflavin from 1950 to 1999 in 43 vegetable crops.16 We can already foresee a beautiful ripe tomato with absolutely no nutritional value.

A discussion of food leads straight to another essential resource, used in every sphere of business across the global value chain: water.

![]()

Water is the new oil, says the conventional wisdom of the 21st century. So how much water did you use today?

If you skipped the shower, you might have guessed three to five gallons (or about 10 to 20 liters). A nice bath, and you are probably hitting around 40 gallons (around 150 liters). So what would be the total water count for the day? Fifty gallons, anybody? Or perhaps 100? Think again!

If you had a cup of coffee, some toast, and an egg this morning, you have already consumed about 120 gallons (about 450 liters) of water—enough for three typical baths! And if these words catch you after a nice steak, you might be surprised that a half-pounder would “cost” you a whopping 1,017 gallons (or 3,850 liters)! These calculations are based on the Global Water Footprint Standard,17 developed through the joint efforts of scientists to allow companies and consumers to deal with the growing water shortages. When it comes to disruption of corporate competitiveness and profitability, the shortages are no joke.

Already today, as the clean water supply is unable to keep up with demand, an estimated 1.1 billion people lack access to safe drinking water.18 No wonder that Paul Bulcke, CEO of one of the largest food corporations in the world, Nestlé, is calling water scarcity the greatest threat to food security in the future. “By 2030, the demand for water is forecast to be 50 percent higher than today; withdrawals could exceed natural renewal by over 60 percent, resulting in water scarcity for a third of the world’s population…. It is anticipated that there will be up to 30 percent shortfalls in global cereal production by 2030 due to water scarcity,” says Bulcke. “This is a loss equivalent to the entire grain crops of India and the United States combined…. Resource shortages lead to price increases and volatility.”19 What a world for us to navigate!

And global water scarcity is only the tip of another gloomy iceberg.

GREEN TECH MAY PROVIDE a way past peak oil There is no escape from peak water.

GUS LUBIN

JOURNALIST

The year 2012 was tough for the US insurance industry. “From Hurricane Sandy’s devastating blow to the Northeast to the protracted drought that hit the Midwest Corn Belt, natural catastrophes across the United States pounded insurers last year, generating $35 billion in privately insured property losses, $11 billion more than the average over the last decade,” the New York Times reported in May 2013.20 Much of that bill was covered by the reinsurers—companies that take on insurance policies from primary insurance companies eager to spread out their risk. And if you were an insurance company affected by Sandy, you’d better pray that you had a reinsurer behind you. What about the reinsurers themselves? One of the biggest companies in this business is Swiss Re. J. Eric Smith, CEO of Swiss Re Americas, says of these concerns, “What keeps us up at night is climate change. We see the long-term effect of climate change on society, and it really frightens us.”21

We might keep debating the science of climate change, going back and forth in politicized discussions of every kind. A stable climate, however, is a key resource for all countries and economies to manage in the years to come. And already today, for one crucial industry—which services much of the global market—the verdict is painfully clear: “For insurers, no doubts on climate change.”22

Just about now, it would be a good idea for me to stop this doom-and-gloom overview of the upcoming Armageddon. But my hope is that you can see past the challenges to the opportunities. When dealing with a heavy load of data, a wonderful friend and one of the best management professors in the world, J. B. Kassarjan, always offers his clients a magic phrase: “Facts are friendly.” Facts are friendly, indeed—and for all the companies pursuing the Overfished Ocean Strategy, they have become a source of competitive advantage. From one set of facts we go to another, traveling from the ocean of resources to the ocean that is getting intensely abused: waste.

WE BUY THINGS WE don’t need with money we don’t have to impress people we don’t like.

DAVE RAMSEY

FINANCE SPECIALIST AND AUTHOR

The Ocean of Waste

As I type these words, the room is filled with light and the smell of peonies. The desk is barely visible under the messy piles of papers and books. An old bag of chips smiles at me from behind the desktop. Always on the move, I have not touched my desktop computer for more than three months. Yet about 1.8 tons of raw materials were used to produce this single machine, which on its own weighs around 30 pounds (14 kg).23 With this level of utilization, my computer will soon come to the end of its life cycle—we will simply clear up the space, getting rid of the unused device. More than 47.4 million computers were thrown out in 2012 in the United States alone, and no more than 25 percent of those devices were recycled.24 If we apply that percentage to my 30-pound computer, with only 25 percent of its weight recycled, that means that barely 0.19 percent of all originally mined materials would go recycled.

Fully 99.81 percent would be wasted.

It would be wasted not because the materials mined and processed to build the computers have no value, but rather because we have not been designing products and processes with that value in mind. Our throwaway economy works on the assumption that it is easier to make a new product than to reuse resources already processed.

But as we enter the 21st century, “throwaway” is going away. The UK warned that it would run out of landfill space by 2018.25 Dubai already approached this limit in 2012, when one of its two key landfills reached capacity and was on the brink of overflow.26 The garbage crises in Naples and Bangalore became so famous that they reached the pages of most major media outlets, the New York Times among them.

With global landfills overextended to the very top of their capacity, no wonder that waste overspills in every direction. Most of us have heard of giant waste fields floating in our oceans. While no scientist has provided a definitive calculation of the size of any of the fields (Massachusetts? the Netherlands? the moon?), CNN refers to one such field as an “enormous, amorphous, nasty soup that stretches for hundreds of miles.”27 The title of the article is no less telling: “The Pacific toilet bowl that never flushes.” Ready for a swim?

Every time I hear these stories of waste, an impatient pragmatism in me demands: so what? For an environmentalist, the answer to this question might imply activism (and pessimism). But for an entrepreneur and manager, the implication is rather different. Architect and designer William McDonough and the rest of the Cradle to Cradle crowd made it into a simple formula: “Waste equals food.” In other words, hundreds of miles of plastic floating in the ocean is an environmental disaster indeed, but it is also a whole bunch of wasted petroleum that could, if approached with intelligence, be turned into a business opportunity. It all depends on the quality of your ideas.

The Ocean of Ideas

A self-made billionaire who starts the Spanx lingerie company from a folding table… a 17-year-old who sells his app to Yahoo for $30 million… organic baby food started at a UK kitchen sold to an American giant…. We have all heard those stories—and (well, I have to speak for myself here) dreamed of being part of them. Could it be that the ocean of business ideas is also running dry?

According to PWC, 2013 started with a 12 percent decline in dollars spent in venture capital investment in the United States and a 15 percent decline in the number of deals.28 Such a decline is projected or already manifested in a number of US states (such as Ohio) and European countries (France comes to mind first) and runs across many industries. What is the issue?

Sandi Cesko, a Slovenian entrepreneur who grew his company from $70 to $700 million in sales amid global crisis to become an entrepreneurial poster child for a Harvard Business Review story,29

put it this way: “We are going through a major transition. In the past, we sold products. Today, we are selling services. But the global overcapacity, coupled with resource crunch, means something new. We simply cannot possibly sell more and more stuff. Tomorrow, our capacity to sell will depend on our ability to stay relevant.” We will have to sell meaning.30

Sandi’s insights echo the work of business-trend watcher Daniel H. Pink. In his best-selling book A Whole New Mind, Dan speaks of the same patterns—or ages—that the global economy has been going through:

Think of the last 150 years as a three-act drama. In Act I, the Industrial Age, massive factories and efficient assembly lines powered the economy. The lead character in this act was the mass production worker, whose cardinal traits were physical strength and personal fortitude. In Act II, the Information Age, the United States and other nations began to evolve. Mass production faded into the background, while information and knowledge fueled the economies of the developing world. The central figure in this act was the knowledge worker. Now the curtain is rising on Act III. Call this act the Conceptual Age. The main characters now are the creator and the empathizer.31

If our ability to compete in the future depends on the ability to create new meaning, how are we to foster this kind of innovation?

The Disappearing Line

Swim through the overfished oceans, connect the dots, and you will get to a bigger picture. Think of the global economy in which we are living today as one long line. The line starts with all the companies that are mining, growing, or raising something—those are our only options when it comes to raw materials. The line finishes with all the companies managing a not-very-sexy but increasingly lucrative business: waste. All other businesses—large and small, products and services—are between these two poles. That is our entire global economy. One giant supply chain.

It is linear—there is only one straight line from the beginning to the end. It is throwaway—as, generally speaking, we use what we mine only once, throwing away most of the resources just the way you throw away a plastic fork after a onetime use. And it is collapsing—as we are running out of things to mine and places to trash.

We are in the midst of the transformation of a lifetime.

For most businesses, this transformation is invisible. For those bearing its crushing impacts, it is disastrous. Yet some see it as the greatest opportunity of the 21st century.

TerraCycle is one such business. Known as the company that produced the world’s first product made from 100 percent postconsumer garbage, TerraCycle has “outsmarted waste” by engaging more than 20 million people in collecting waste in over 20 countries and diverting billions of units of waste. Now a company that turns waste into over 1,500 different products, TerraCycle was once a laughingstock of the entrepreneurship competition. The first product of the company, founded by a barely 20-year-old Princeton dropout, Tom Szaky, was far from glamorous but made up for it with a great name: Worm Poop. An all-natural fertilizer, Worm Poop is packaged in recycled plastic bottles, which the company collects in part through a US-wide recycling program. The New York Times’ Rob Walker wrote:

You don’t hear much about worms, or their waste, from the various big-box retailers, globe-trotting pundits and good-looking guests of Oprah Winfrey who appear to be leading the conversation about environmental concern these days. But TerraCycle’s plant food is actually a mass-oriented variation on something that hard-core eco-people talk about all the time: the worm bin. Containers filled with shredded newspaper and worms, such bins are used for composting food scraps. Worms eat this waste and digest it, and “compost exits the worm through its tail end,” one online guide explains. These “castings”… happen to make good plant food.32

TerraCycle now sells at major retailers ranging from Walmart to Whole Foods Market. Look who is laughing now!

THE STATUS QUO IS a very powerful opiate, and when you have a system that seems to be working and producing profits by the conventional way of accounting for profits, it’s very hard to make yourself change. But we all know that change is an inevitable part of business. Once you have ridden a wave just so far, you have to get another. wave We all know that. For us, becoming restorative has been that new wave, and we have been riding it for 13 years now. It’s been incredibly good for business.

RAY ANDERSON

FOUNDER, INTERFACE INC

There is no question that turning the challenges of the overfished ocean into a vibrant business opportunity is much easier for a startup than it is for a corporation with a history. Don’t get me wrong: I have nothing against the sweethearts of disruptive innovation for a resource-deprived economy, the Body Shops and the Whole Foods Markets of our world, built from the very start on a solid foundation of Overfished Ocean Strategy principles. Yet with all due respect, I often feel that they almost have it easy, and it is the traditional companies striving to transform into a more competitive version of themselves that are up against a real challenge. Of course, it is an immense task to build the world’s best vacuum cleaner, but just imagine what it would take to transform that working vacuum cleaner into the world’s best TV set? That is the scale and complexity of transformation required here.

Bayerische Motoren Werke AG—also known as BMW—is one such company navigating the murky waters of the resource crunch. The company moved well beyond selling products to selling services—and from a car company transformed itself into a mobility company. Focusing on mobility—a service rather than a product—allows the company to power up radical innovation and open doors to a completely new business opportunity. Take, for example, the DriveNow car-sharing service, employing BMW i, MINI, and Sixt cars, which allows people in densely populated urban areas to enjoy the benefits of a personal car without owning one. The idea, as BMW explains, is simple: “The mobility concept is based on the motto ‘pick up anywhere, drop off anywhere.’ Billing is per-minute, fuel costs and parking charges in public car parks are included. Users can locate available cars using the app, website or just on the street. A chip in the driving license acts as an electronic key.”33 Now, that is a service I am ready to explore!

ParkatmyHouse—a strategic investment by BMW i Ventures—is another example of BMW’s remarkable resource intelligence and ingenuity. A simple online marketplace, powered by an app, allows people who own private parking places to connect with people who are searching for one. Imagine the savings of time, fuel, CO2 emissions, and more—and money made—on this simple solution. And for BMW itself, having a stronger parking infrastructure is essential for future sales: if we have good parking, we are ready to drive cars, right?

Mobility services are not the only radical innovation coming out of BMW. In an effort to protect and defend profits, the company decided to harness winds thrashing across eastern Germany to secure power as costs rise as a result of Germany’s EUR 550 billion ($740 billion US) shift away from nuclear energy. BMW’s transitions seem deceptively simple. Yet when the market forces inspire you to shift your focus from designing cars to designing mobility, disruptive innovation follows; any designer and engineer will tell you that most innovation happens on the verge of the impossible.

Similarly deceptive is the move toward control of the entire energy value chain—but the numbers and the endorsement of business analysts, such as those quoted in Bloomberg’s 2013 review, speak volumes.

At BMW’s Leipzig plant, the four 2.5-megawatt [wind] turbines from Nordex SE will eventually generate about 26 gigawatt-hours of electricity a year, or about 23 percent of the plant’s total consumption, said Jury Witschnig, head of sustainability strategy at the Munich-based manufacturer. The automaker seeks to eventually get all its power from renewables, compared with 28 percent in 2011—both to cut its carbon output and to benefit from falling prices for wind and solar energy. “There will definitely be more such projects” from renewable sources, Witschnig said. “Energy prices are part of the business case,” and in Leipzig, wind power was cheaper than other options.34

But that is not all. BMW’s rapid marriage with the energy business is a sign of remarkable foresight. As legislation continues to press for fewer and fewer emissions (Euro VI requirements being one such pressure), the movement away from combustion engines appears inevitable. Electric vehicles are one alternative—and judging by the fast pace of model launches in this domain, it seems to be a viable option. Yet when you manufacture combustion engines, the emissions are fully in your control, as your engineers are the ones designing an intelligent (or not so much) motor. When we move to electricity, however, that control disappears, as emissions are now dependent on the efficiencies of power plants. And that is exactly why BMW’s tango with energy production is so ingenious: it puts control back in the hands of the company—way ahead of the competition.

Swiss Re is another giant riding ahead of the wave and turning disappearing resources into a thriving business model. The primary product of Swiss Re, a 150-year-old reinsurer with over $33 billion in revenues as of 2012, is insurance for insurers, so the company can hardly be equated with coal-burning plants or methane-producing industries. A company rooted in Swiss rationality and conservatism, the reinsurer surprised the entire industry by taking on the increasing lack of climate stability as a business risk—and opportunity—as early as 1994. By 2007, Swiss Re had introduced a number of financial tools for dealing with the risks associated with climate change. As Nelson D. Schwartz of Fortune magazine explained,

Buyers can bet on future heat waves or cold snaps with puts and calls on specific periods of time and temperatures, much as conventional options have a preset strike price for a stock. So a farmer in India might be able to buy insurance from a local insurer in case the usual monsoon rains fail to arrive, or, conversely, his fields are flooded.35

In the following years, the company upgraded its entire portfolio and pricing to respond to the rising costs of climate change. Speaking to Bloomberg TV in 2009, Swiss Re’s senior climate advisor, Andreas Spiegel, took no prisoners, estimating weather-related losses at $40 billion annually:

Weather-related insured losses are rising, and the intensity of weather-related events such as hurricanes is going up as well. We are integrating these risks in our pricing, trying to quantify certain aspects of climate change and integrating them into our models. Climate- and weather-related risks are a part of our core business. More and more, we see this as a business opportunity, as adaptation to climate change is about managing risks in the long term. And that is our business.36

![]()

Whether red, blue, or rainbow colored, whether made of resources, waste, or ideas, our oceans are running dry. We can continue to ignore this trend, falling deeper into the coma of denial along with millions of other businesses. We can run and hide, pushing it to the bottom of the corporate agenda, waiting for a better time to make a move. Or we can turn the overfished ocean into the driving force for radical renewal. So what should business do?