CHAPTER 6

Principle Four: Plan to Model

AT A GLANCE

MODERN MANAGEMENT HAS A thing for putting life in boxes. We are obsessed with making neat, controllable plans broken into clear, manageable steps. Yet the companies mastering the Overfished Ocean Strategy seem to live in a different universe—one that is messy, iterative, and full of happy (and devastating) accidents. Every company that dared to venture into the unknown terrain from line to circle had to do so in the near dark, each step leading to the next, experimenting, taking action, and producing results long before a truly comprehensive strategy could be articulated. In other words, they had to learn their way into the Overfished Ocean Strategy. Welcome to the exciting world of continuous business modeling.

It happens to me with a surprising frequency. A short e-mail, a quick phone call, a Facebook post, and suddenly you feel like all is right with the world. Like there is true justice. Like good guys really do finish first.

This was one of those e-mails.

Brief and to the point, professional as ever, Iztok Seljak, president of the Management Board of Hidria, shared the happy news: beating more than 15,000 other companies, Hidria Corporation won the title of Europe’s most innovative company of 2013. That put a smile on my face!

Over the past decade, Seljak, a fearless leader, an inspiring colleague, and a frequent speaker at my executive MBA classes, has championed his team to invent its way out of disappearance. A company with a rich past, Hidria found itself in search of new history by the early 2000s.1 With its core competence in producing electric motors for cooling and heating systems, the question was: Is there anywhere else this skill might be useful? It turned out there was.

With the turn of the century, the pressure to reduce harmful emissions, coupled with rapid growth in the price of fuel and the development of battery technology and infrastructure, finally made an electric motor into a legitimate new business idea. Figure 5 shows one way to visualize this pressure.2

The left side of the graph represents the amount of emissions that European Union regulation allowed for passenger cars under the EU

I mandate. The right side of the graph represents the amount of emissions permitted under the EU VI mandate, including minuscule permissible levels of particulate matter (PM) hiding in the bottom-right corner. It is easy to notice that all permissible levels have gone down at a staggering rate, with the burden of innovation to meet the legal demands pressing heavy on the backs of car manufacturers. While fuel cell and other technologies are still far from mass commercialization, the introduction of electric motors for hybrid or pure electric vehicles was the easiest way to meet the demands of the new legislation. The problem was that very few automotive powerhouses in the world had a strong competence in building an electric motor, and even fewer automotive suppliers had been innovating in this domain.

Figure 5. Emissions of hydrocarbon, nitrogen oxide, and particulates allowable for diesel passenger cars under EU regulations between 1992 and 2014.

But a company producing electric motors for air conditioning and heating systems did. In 2004, Hidria turned its business on its head by adding “green” mobility to its mission, vision, and core strategy. In the first year of operations, 2005, the new automotive division brought in EUR 10 million (about $13 million US) in revenues. By 2012, amid the global economic recession, Hidria reached the profitable automotive revenues of EUR 150 million (nearly $200 million US). Today, the engine of every fifth new diesel-powered car globally is ignited by Hidria’s ignition solutions, every fifth new car in Europe is steered by Hidria’s electrical power-steering solutions, and every third new car in Europe is powered by Hidria’s hybrid and electrical power-train solutions, including esteemed top-of-the-line models produced by Audi, BMW, Mercedes-Benz, Porsche, Ford, Peugeot, Renault, and Volkswagen. It took a mere seven years. That’s all.

There is no question that everyone likes this kind of Cinderella story: from nothing to top of the world in a few easy steps. The most interesting question, of course, is: How did Hidria get there?

![]()

“Why did we enter electric mobility? We were young, full of new ideas, and hungry to go beyond following to leading. When we started, the entire automotive industry had already proclaimed this domain of innovation as a worthless, short-lived fad nondeserving of any significant attention. Thankfully, we did not know that at the time.” The entire Executive MBA classes chuckles as Seljak reflects back. But that is exactly where the secret of Hidria’s success lies: the ability to constantly look at their business anew. They call it “embedded business model innovation.”

Seljak explains: “They all think that it is all about technological innovation. That, of course, is important. But it is not what truly makes the difference. Time and again, our victories depend on the ability to imagine an entirely new way of adding value. That is what business model innovation is about—value creation, reimagined. Continuously.”

Hidria’s success has been built on this approach. When the company developed new technology suitable for a hybrid motorbike, the OEM decided to neglect the innovation as hardly appealing to the traditional rough-around-the-edges, testosterone-driven biker bunch. Refusing to take no for an answer, Hidria, which had no knowledge of business-to-consumer communications, developed a comprehensive marketing and communications package built around the idea of “One bike, two hearts” to combat the negative image of hybrid technology among lovers of motorsport. This ability to go beyond technology transformed a newcomer into a development supplier—and then into a predevelopment supplier, serving as a true thinking partner to car companies well before a particular model is developed.

But the embedded business-model innovation is not contained within a particular product line or division. All divisions of Hidria got on board with thinking differently—and imagining an entirely new set of solutions for a resource-deprived world. With three new research-and-development institutes (each stocked with a range of laboratories), the company is constantly pushing forward with development of comprehensive, financially viable mobility and indoor air services. Turning solar power into a cooling/air-conditioning system (instead of a heating and electricity system) is a technical innovation; figuring out how to make it work financially as a viable product is a business-model innovation. Often, Hidria alone cannot achieve such innovation, so the company uses a number of “coopetition” projects, collaborating with its competitors for whole-system (remember, horizontal, not vertical!) breakthroughs. In 2011, together with seven of its competitors and the Slovenian government, Hidria became a founding partner of a new for-profit private public partnership, SiEVA, focused on codevelopment of technological solutions for ecologically clean cars.3 In 2012, the company initiated a new sustainable-construction consortium, putting its climate-control solutions to good use. Uniting more than 40 companies across Europe, the Feniks consortium today brings together a workforce of 35,000 people with an annual revenue of EUR 4.5 billion (around $6 billion US). Building for the Sochi 2014 Olympics is among the first big victories for the consortium.

Now an award-winning initiative, Feniks justifies its existence in this way:

We live in the era of significant global changes, requiring an ever-increased sustainability of our overall future development. Along with the ongoing economic crisis, we are facing new challenges and numerous new opportunities also for sustainable construction. Today, we burn 40 percent of fossil fuels through buildings—i.e., to cover their demands. Sustainable construction, due to its overall importance, is becoming one of the most important segments in the focus of development of the European Union and wider. Concrete goals have been set, including a decrease in energy consumption, increase of available energy from renewable sources, minimization of harmful effects on the environment, and profound care for natural resources, while following the key guidelines of creativity and innovation.

In the coming years, construction is therefore set to go through considerable shifts and changes in overall concept, design, and execution. As a result, organizations that will be able to integrate and efficiently manage all of the required key building blocks for providing the sustainable buildings of the future will be gaining in importance. The new approaches in construction will include the ability to integrate the buildings in the natural environment in ways not known so far, and the ability to finance and/or manage the buildings’ vital functions longer term, providing the lowest life-cycle costs and offering the maximum of indoor well-being. As a consequence, the role of cooperation and partnerships, gathering the best global knowledge, will also be gaining in importance. In order to proactively, comprehensively address all of these core issues, we are gathering the most creative and innovative construction companies in southeastern Europe, with rich tradition and new creative ideas and required competences to realize them. Traditional presence and important references in and around the Russian Federation, the Near and Middle East, and Northern Africa, as well as new, innovative breakthrough solutions in proprietary digitalized tools for virtual construction, complete energy management systems, innovative systems of thermo-solar and photovoltaic solutions, and new materials and processes, are all ensuring the best integration of excellent individual niche competences of each of the Feniks members into an exclusive flexible and highly competitive set of turnkey capabilities for sustainable buildings of the future.4

That is what inventing a new business model looks like. United we stand!

Around the world, companies similar to Hidria are waking up to the disappearing linear throwaway economy—and discovering ways to embed a new thinking into their strategy, products, and operations. Their approach is anything but “normal.” In fact, normal—statistically speaking—looks entirely different.

Your New Modeling Career

What do we do when we want to launch something new? How do we turn a hunch, an idea, into a true, commercially successful innovation?

The “normal” decades-old path looks something like this: develop a solid, detailed plan (five years seems to be the assumption behind most business plans); get financial backing (budget approval in the existing corporation or investment/loan for a start-up); develop your product to perfection; and sell as much as you can.

The reality of the overfished ocean, however, throws a serious curveball into this well-known trajectory. In the face of the collapsing linear throwaway economy, resources and expectations are becoming increasingly volatile. Oil prices alone can bring the entire economy into shock. McKinsey estimates that a price of $125 to $150 a barrel, sustained for years, “would drive down global growth by 0.6 to 0.9 percentage points in the first year. Over time, as economies adjusted to the new higher prices (and shifted to different types of fuel, technologies, and production techniques), the impact would diminish. But the rate of global GDP growth would be affected for years. By 2020, the global economy would be between $1.1 trillion and $1.7 trillion smaller than the baseline outlook: the equivalent of losing Spain’s or Italy’s output for a year.”5 The price volatility of every other commodity is no walk in the park, either—plus, consumer, investor, and legislative pressures are equally unpredictable, intensified by radical transparency and easier-than-ever consumer and civil activism, all fueled by the advancements in social media technology.

In the world of overfished oceans, planning is overrated. In the face of extreme uncertainty, plans become obsolete in no time. The only way to make the new reality work is to find a way to constantly adapt your business to the new reality—treating it as a strategic priority rather than a short-lived sidekick to the core business. And for the companies mastering the Overfished Ocean Strategy, business modeling, rather than strategic planning, is the name of the game. Unlike cumbersome, static, and rigid plans, models are agile, evolving, and open to change. Modeling, rather than planning, is the key to turning line into circle—and making money in the process.

![]()

In contrast to business strategy, which is essentially about the best way to get from point A to point B, a business model is about the vehicle you use for traveling—the mechanism that allows you to create, deliver, and capture value. An essential element of strategy development, a business model is a design—a unique combination of driving forces that allow you to enact a commercial opportunity.

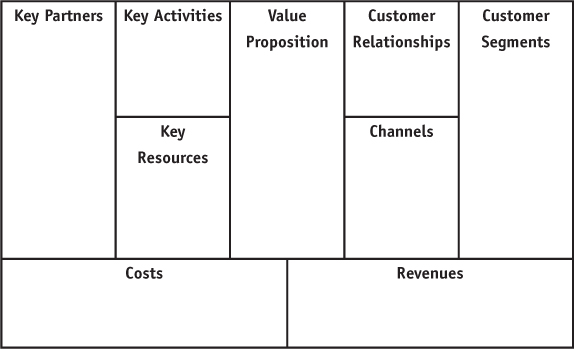

In 2010, a group of 470 practitioners led by Alexander Osterwalder and Yves Pigneur cocreated a common language for what a business model looks like when developed and communicated within and beyond the company.6 Known as a Business Model Canvas, the tool helps us grasp value creation in a clear and simple picture that looks something like Figure 6.

A simple and clean tool, the canvas helps us capture the essence of our business model—and figure out a new way to reinvent it. The process is so simple that it is almost ridiculous. To start, you take a product or a service and fill out the canvas with every bit of detail. You might be surprised to discover completely different ways to understand your customers and their needs—and then create real value delivered in the most meaningful way. Continuous business-model innovation is the systematic reimagining of the key driving forces within the model—and rethinking the way each driving force relates to the others.

Consider, for example, the story of OneWorld Health, founded in 2000 as the first nonprofit pharmaceutical company in the United States. When Drs. Victoria Hale and Ahvie Herskowitz decided to start the company, the problem was simple: hundreds of millions of people around the world were suffering from what became known as orphan diseases—Third World malaises that no Western pharmaceutical company wanted to take on for the lack of a substantial profit prospect. The solution: develop a business model that would turn orphan diseases into a viable opportunity. Since much of the pharmaceutical investment goes into the research-and-development pipeline—searching for drug leads and then developing them via an expensive trial process—OneWorld Health realized early that they needed to find another process to fit their pocketbook. The company leaders also realized that many pharmaceutical businesses already had drug leads for orphan diseases—which they had discovered accidentally while researching other drugs—that were sitting idle on the shelves as wasted resources. OneWorld Health went to for-profit pharmaceutical companies and suggested that they donate drug leads that had little commercialization potential in the West, with the benefit of a tax deduction. Then the company worked on developing the leads into safe and effective medicines in partnership with scientists and manufacturers in the developing world, thus significantly reducing the costs and bringing the medicine to consumers at an affordable price.

Figure 6. The Business Model Canvas offers a great exercise for understanding and strengthening your value creation.

The success of OneWorld Health had little to do with technical innovation, as the company uses rather mainstream technologies that are well developed and far from new to make things happen. Instead, this pharmaceutical company thrived due to business-model innovation—connecting different stakeholders in a unique and inventive way to deliver new value. Business modeling is fast becoming the competence to master.

The American company Safechem, a subsidiary of Dow Chemical, changed its business model from selling products to selling services—providing customers with a complete cleaning service instead of selling chemical cleaning products. The service is based on a closed-loop line-to-circle system where solvents are delivered, used, and taken back. Customers are billed on the basis of product performance—for example, chemicals used per square foot instead of per product used. That way, Safechem’s revenue depends on the volume of cleaned surface instead of the volume of solvents sold, making its business model much more resource intelligent. It is estimated that Safechem’s chemical leasing service has the potential to reduce solvent usage by 63 percent—and mitigate many other environmental impacts.7 Again, the company’s performance—including cost savings on chemicals—was the result of business-model reinvention rather than any kind of technological breakthrough.

Norwegian company Allfarveg is an example of a business-model innovation based on the design-build-finance-operate (DBFO) model. DBFO business undertakes capital-intensive, long-term construction projects where private finance, construction, service, and/or maintenance are bundled into a long-term, multidecade contract. Such contracts provide the incentive to improve the quality of the construction, thus lowering the life-cycle costs of the projects. Allfarveg was created to design, build, finance, operate, and maintain the new road between Lyngdal and Flekkefjord in Norway. Having a 25-year contract with the Norwegian Public Roads Administration, Allfarveg gets paid based on the performance of the road. Such an incentive structure led Allfarveg to implement a number of not-so-usual techniques and solutions, such as using brighter stones in the asphalt, which require less light intensity to illuminate the road at night. This simple change resulted in a 30 percent reduction in electricity costs and a savings in resources used for electricity—all while the road-construction work was completed two years ahead of time.8

That is business-model innovation.

THE SAME PRODUCTS, SERVICES, or technologies can fail or succeed depending on the business model you choose. Exploring the possibilities is critical to finding a successful business model. Settling on first ideas risks the possibility of missing potential that can only be discovered by prototyping and testing different alternatives.

ALEXANDER OSTERWALDER

AUTHOR, BUSINESS MODEL GENERATION

Companies and managers mastering Overfished Ocean Strategy do something different. They take the collapse of the linear throwaway economy as an opportunity to rethink their entire strategy and use it as a source of business-model innovation. They abandon the heavy, static, flawed plans and develop the capacity for deliberate and continuous business-model innovation, increasing their own agility and adaptability in the process. And it happens to be one of the leanest, most efficient ways of running your organization.

Leaning up

In spring 2013, my husband and I decided to enter into a new business. As the negotiations with the potential partners started in March, among the first key documents for us to explore—and work on—was a business plan. Intense work by a whole team of solid thinkers produced a document of solid assumptions, clear goals, and extensive coordinated steps to achieve them. Since we took on the task of upgrading an existing business with an existing product, by the end of April, we were rolling. By late May, the prices of raw materials and transportation shifted while sales results suggested an entirely new opportunity. Our business plan became obsolete.

It turns out we were not alone. Increasingly, companies big and small, new and existing, are figuring out that the traditional model of planning, product development, and execution generates wasted resources and marginal returns—resources that our resource-deprived economy can no longer afford. A new movement has emerged that makes this process less wasteful and less risky. And it borrows its key principles from a concept central to resource intelligence: lean manufacturing.

![]()

In 1937, a small company manufacturing automatic looms for the textile industry produced an unusual spinoff—a newborn daughter business focused on the needs of the automotive industry. By July 2012, this little child had grown to become the 11th-largest company in the world by revenue and produced its 200 millionth vehicle. It had also created one of the best-known operations and manufacturing philosophies in the world—the Toyota Production System.

Built on the idea that nothing should go to waste, and every resource used in business should directly contribute to value, Toyota’s approach was expanded and enhanced to become lean manufacturing9—the term coined by John Krafcik in his 1988 article “Triumph of the Lean Production System,” published in the Sloan Management Review.10 The idea of lean is simple: everything we do should be useful; nothing we do should be wasteful. A simple waste of time—such as employees’ waiting for supplies to be delivered to the manufacturing line from the central warehouse—decreases our productivity, but that is not the only waste. When we sit and wait, we are also using the real estate inefficiently: we waste energy, water, and other raw materials used to run an idle plant, and all of that is multiplied by waste generated at every other step of production, sucked into our bottleneck. An alternative? Develop a lean mind-set—a way of looking at your business from a waste-less prospective.

Traditionally, the idea of lean has been focused on the operations process itself, rather than business strategy. But the movement born in the past few years took the concept of lean to an entirely new level—applying it to starting up new businesses, new divisions and products, new strategies. Welcome to the lean start-up.

Here is how new things get started in business (most of the time). First, the company starts with a product or service idea, which immediately gets backed by a business plan. After a few months, in the most painful way, the entrepreneurs discover that the plan has failed. In a 2013 Harvard Business Review article, Steve Blank explained the reasons:

Business plans rarely survive the first contact with customers. As the boxer Mike Tyson once said about his opponents’ prefight strategies, “Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.” No one besides venture capitalists and the late Soviet Union requires five-year plans to forecast complete unknowns. These plans are generally fiction, and dreaming them up is almost always a waste of time…. The founders of lean start-ups don’t begin with a business plan; they begin with the search for a business model. Only after quick rounds of experimentation and feedback reveal a model that works do lean founders focus on execution.11

The lean start-up model, while developed for new enterprises, offers a wonderful framework for companies interested in conquering the overfished ocean. While the traditional business focuses on business plans, lean start-ups concentrate on business models. While the majority build their products after full specification and launch them with the help of a linear, step-by-step plan, lean enterprises get out of the office and test their hypotheses, building their products iteratively and incrementally with a lot of customer input. And while most of us treat failure as a rare, unexpected abnormality, lean companies expect failures as the right and necessary element of business-model innovation—and fix them by iterating the ideas away from the features that did not work.

The model championed by the lean start-up movement is exactly what the Overfished Ocean Strategy companies have been doing for years, if not decades. The secret of making this strategy work is to move from business plan to business model—and experiment relentlessly with products, services, and processes for continuous radical innovation. As you develop your plan-to-model skills, a few tools might come handy.

FAMOUS PIVOT STORIES ARE often failures, but you don’t need to fail before you pivot All a pivot is is a change [in] strategy without a change in vision. Whenever entrepreneurs see a new way to achieve their vision—a way to be more successful—they have to remain nimble enough to take it.

ERIC RIES

AUTHOR, THE LEAN STARTUP: HOW TODAY’S

ENTREPRENEURS USE CONTINUOUS INNOVATION TO

CREATE RADICALLY SUCCESSFUL BUSINESSES

Building Your Tool Kit

Starting with the first homework in kindergarten, we are trained to conquer our world with a solid plan. As we grow, the plans get bigger, becoming their own art form once the level of business planning is reached. But in the world of disappearing resources, collapsing landfills, and increasing expectations from customers and every other stakeholder, planning is a futile activity doomed from the get-go. Business modeling, in contrast, offers a solid pathway to creating, delivering, and capturing value that is much more nimble, real-time, and appropriate for the reality of the overfished ocean. A good set of tools has been developed and polished by hundreds of business practitioners—and might just offer the perfect plan-to-model pathway. Here are a few you might consider for your own Overfished Ocean Strategy tool kit:

• The community behind the Business Model Canvas has been growing by the minute, with countless resources available online. The IDEO innovation and design agency offers great tools for business-model visualization; you can find their videos on YouTube, as well as resources and cases from their Business Design division on their website at http://www.ideo.com/expertise/business-design/.

A 2010 book that made this movement explode is titled Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers, by Alexander Osterwalder and Yves Pigneur, developers of the Business Model Canvas described earlier in the chapter, and it has a very strong, vibrant presence, online and via face-to-face gatherings. Here, you can find a free 70-page preview of the book, a list of events you can join in your country, tools, videos, and much more. There is also an app that allows you to create your own business-model canvases in a blink of the eye, as well as an app called Strategizer that allows you to collaborate with your team, perform all essential calculations, learn essentials through minicourses, and manage the entire project with clear tools. Learn more about business-model generation at http://www.businessmodelgeneration.com/.

• The lean start-up movement is another excellent resource for the rationale and practice of the transition from plan to model. The poster child for the movement is the 2011 book by Eric Ries titled The Lean Startup: How Today’s Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses (New York: Crown Business), and you can learn more about the movement, including a few great cases, at http://theleanstartup.com/.

Many other articles, books, and tools have been developed based on this idea. Tim O’Reilly, CEO of O’Reilly Media, described the benefit of this approach in the following way: “The Lean Startup isn’t just about how to create a more successful entrepreneurial business… it’s about what we can learn from those businesses to improve virtually everything we do. I imagine Lean Startup principles applied to government programs, to healthcare, and to solving the world’s great problems. It’s ultimately an answer to the question ‘How can we learn more quickly what works, and discard what doesn’t?’”12 If this level of efficiency and resourcefulness sounds right for you, you might start exploring the lean-start-up model with Steve Blank’s article “Why the Lean Start-Up Changes Everything,” which appeared in the May 2013 issue of Harvard Business Review: http://hbr.org/2013/05/why-the-lean-start-up-changes-everything.

• While both of these movements have been around for just a few years, the idea of holistic, adaptive, emergent strategic thinking is by no means new. Henry Mintzberg, one of the best strategy and learning thinkers of our time, made the case for a more emergent approach to strategy in his 1994 book appropriately titled The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall). He spoke of the rise of strategic planning, which in the mid-1960s was hailed as “the one best way” to develop and implement strategies for achieving a competitive advantage for every business unit. It was then, following the suit of scientific management pioneered by Frederick Taylor, that companies decided to separate thinking from doing, giving birth to a new corporate function—strategic planning. Fifty years after that fateful decision, and 20 years after his book on planning came out, Mintzberg’s words are as powerful as ever: “Planning systems were expected to produce the best strategies as well as step-by-step instructions for carrying out those strategies so that the doers, the managers of business, could not get them wrong. As we now know, planning has not exactly worked out that way. While certainly not dead, business planning has fallen from its pedestal. But even now, few people fully understand the reason: strategic planning is not strategic thinking. Indeed, strategic planning often spoils strategic thinking, causing managers to confuse real vision with manipulation of numbers. And this confusion lies at the heart of the issue: the most successful strategies are visions, not plans.”

Business modeling is the process of describing and organizing the vision in a compelling and clear way, thus making you able to inspire and mobilize everyone involved. In your transition from plan to model, Henry Mintzberg’s work might be very helpful. You can start by exploring his January–February 1994 Harvard Business Review article, whose title humorously turned the name of his book upside down: “The Fall and Rise of Strategic Planning”; http://staff.neu.edu.tr/~msagsan/files/fall-rise-of-strategic-planning_72538.pdf.

![]()

Transitioning from planning to modeling—like any other principle of the Overfished Ocean Strategy—is one solid way to power up innovation for a resource-deprived world. Yet to make this strategy work, one more crucial transition must take place. Often, this one is the most difficult of all.