3

Forging Strategic Identity

If the best and the brightest of one generation—in any generation, in any country—get together into one company . . . then there’s a feeling that, gee, we can do something really good.

—Jorma Ollila, Nokia

LIKE ALL GENERAL MANAGERS, higher-ambition CEOs face the challenge of creating sustained competitive advantage. However, we found that these leaders are distinctive in their realization that they cannot divorce a firm’s strategy from the sensibilities and passions of its people. The story of Nokia illustrates how one of the higher-ambition leaders in our study, Jorma Ollila, helped that company return from the brink of extinction by forging a new, more powerful understanding of its distinctive character and unique capabilities to create economic and social value, what we think of as its fundamental strategic identity.

In the fall of 1991, Nokia was in tough shape. “This was not a company that was supposed to survive,” said Ollila, Nokia’s former CEO, during a conversation with Flemming Norrgren and Tobias Fredberg at the company’s offices in Espoo, outside Helsinki. Finland, where Nokia is based, wasn’t in much better condition at the time. “Finland, as an economy, was a basket case,” Ollila told us, speaking in English in his deliberate, thoughtful way. “Everybody was thinking, ‘This is soon going to be a forgotten hinterland.’”

But Ollila had no intention of letting that happen to his company or, if he could help it, to his country. In Finland, company and country are tightly associated. Finland has had a long struggle to establish its national identity. Little Finnish literature of note was published before the nineteenth century, and the country was long a part of Sweden, before becoming a grand duchy under Russian rule. It declared independence in 1917 and bitterly resisted invasion by the Soviet Union during World War II, but had to cede substantial territory. In this context, Nokia, in particular, has played the role of a Finnish national champion. Founded and led by families considered to be of true Finnish provenance, Nokia has been a perennial export leader. Ollila himself hails from an old, prominent Finnish family.

While others viewed Nokia as a failed company in a troubled economy, Ollila saw potential and unbounded opportunity instead. In our conversation with Ollila, he explained how he and his team set out on a journey of transformation that, at its core, involved crafting and then capitalizing on a new strategic identity. His reflections bear remarkable similarities to the stories we heard from the other CEOs in our sample. To a degree that struck us as genuinely distinctive, these leaders:

- Craft a strategic identity that connects head, hands, and heart.Through an intuitive, iterative, broadly engaging process, higher-ambition leaders define their firm’s sense of strategic identity in a way that harnesses a distinctive core of people and capabilities (hands) to a meaningful purpose and core values (heart), and underpins a sustainable economic model (head). The extent of engagement involved in crafting a strategic identity strengthens the courage needed to follow through on the difficult decisions that the execution of the strategy may require.

- See organizational capability as strategy.Strategy and organization, for these leaders, are not separate domains. Rather, these leaders view superior organizational capability as a cornerstone of their strategy, and choices about organizing models as among their most strategic decisions.

- Commit, yet adapt.Higher-ambition leaders follow through, year after year, continuing to make investments that bring additional advantages or that leverage those advantages into new markets. Yet while emphasizing strategic consistency, they are highly attuned to the need to adapt and innovate continually. Many confronted difficult portfolio choices and spoke of the challenges of maintaining the social fabric and continuing to create a sense of shared identity and direction in the face of wrenching decisions.

Craft a Strategic Identity That Connects Head, Hands, and Heart

Until the early 1980s, if someone asked you to identify the core of the Nokia enterprise, you would probably have concluded that it was paper products or even rubber boots. Nokia is a conglomerate formed in 1967 through the merger of three venerable Finnish companies: Nokia Ab, a paper company, founded in 1865; Finnish Rubber Works, established in 1898; and Finnish Cable Works, founded in 1912. The conglomerate eventually comprised five main businesses—rubber, paper and forestry, wire cables, power generation, and electronics. The company’s name comes from the nokia, a minklike animal that dwells in the environs of the Nokianvirta River where the paper company established one of its early mills.

The late 1970s and early 1980s were exciting times for Nokia. The company’s then CEO, Kari Kairamo, decided to push the company away from rubber boots and paper and toward the electronics and high-technology businesses that were taking off at the time. He used the profits from the company’s legacy offerings, including the high-top Kontio rubber boots (a big seller), to make a series of acquisitions and investments, the largest ones in color television manufacturing and data systems. In 1982, most of the company’s sales came from products like rubber boots and tissue paper. By 1988, electronics accounted for 60 percent of its sales, and Nokia had become Europe’s third-largest producer of color televisions, with around 14 percent of the market.

The strategy was bold and high risk. Many of the acquired businesses had been struggling before Nokia purchased them, and Nokia had gambled that it could turn them around. In December 1988, Kairamo committed suicide, and in March 1989, Nokia reported that it had suffered a steep decline in profits relative to the previous year, almost entirely due to poor performance in the electronics division.

Turmoil in the business environment deepened Nokia’s predicament. The Finnish economy was already struggling when the Soviet Union, which purchased as much as 20 percent of Finland’s exports each year, collapsed. This, combined with weakening demand for television and video products in key European markets, dealt a body blow to Nokia and to the economy of Finland.

The new CEO, Simo Vuorilehto, was forced to undertake a substantial restructuring. Nokia sold its footwear operations to a management group and in November 1990 exited the tissue paper business. In early 1991, Nokia was in such disarray and uncertainty that the board sought help from an outside adviser. It commissioned a study of the company’s strategic options by the European technology practice of a leading global management consultancy. The consultants spent several months studying Nokia’s operations and opportunities and prepared a report they presented to the board in the fall of 1991.

A central issue that the consultants addressed was the future potential of Nokia’s cell-phone business. As part of Kairamo’s electronics push, in 1979, Nokia had entered a joint venture with Salora, a television maker, to develop radio telephones. In 1981, the Nordic Mobile Telephone (NMT), the first international mobile phone network, was established. Nokia introduced a car phone for the network in 1982 and brought its first portable phone to market in 1986. Meanwhile, in 1982, the European Conference of Postal and Telecommunications Administrations (CEPT) established a group to develop an international standard for mobile telephones, to be called GSM, the standard today. These moves and developments gave Nokia an early jump into the new and potentially exciting cell-phone industry. In 1988, it expanded its cordless phone operations by paying £2.5 million for a 25 percent stake in Shaye Communications, based in the United Kingdom. In February 1991, despite its financial and cash difficulties, Nokia bought Technophone, a British company. Suddenly, Nokia was the world’s second-largest cell-phone company, after Motorola.

The consultants’ report was not optimistic about Nokia’s prospects. It said that Nokia was, in effect, a “hopeless” case and singled out the cell-phone business as a particularly “dubious” option. The consultants believed that Nokia did not have the basis for sustainable competitive advantage in cell phones and should, in fact, exit the business immediately. It is easy to understand why the consultants reached their conclusion: Nokia, struggling financially and on the periphery of major markets, appeared to lack the breadth and depth of the major telecommunications or electronics firms’ resources.

“You could see that they thought they were very smart when they walked into the room,” Ollila remembered, with his characteristic half-smile. But Ollila was having none of it. “I told some of the board members, ‘If you believe these guys, go away. Because that’s wrong.’”

The board nonetheless chose to heed the consultants’ advice and offered Nokia’s mobile division for sale at a knock-down valuation to Ericsson, the Swedish telecommunications company. Yet after two months of deliberations and evaluations, Ericsson dropped out and passed on the offer. “They said, ‘We don’t want to touch this thing,’” Ollila recounted.

The collapse of the sale left the board between a rock and a hard place. Rather than look for another buyer, it decided that perhaps Ollila was right. Maybe the mobile telephony business could form the core of the company’s future strategy. Nokia was, after all, number two in mobile telephony worldwide—even if the market was small—and its revenues had been growing. “There were some people on the board of directors who said, ‘Okay, the only thing is to get a bunch of young guys and see what we can do with this,’” Ollila told us. At the time, although Ollila was the head of the cell-phone business, he did not expect to be the young guy the board would tap to run the entire company. In January 1992, the board appointed Ollila as Nokia’s new president. “It was a surprise totally for everybody, including myself,” Ollila told us. “A total generation change. Big risk.”

A big risk, perhaps, but there were few other options. “People had already lost their money,” Ollila said. Market capitalization had fallen to less than $1 billion. Nokia had to do something dramatic or it would very likely cease to exist.

The board’s bet on the cell-phone business, which the consultants and Ericsson had shunned, and its choice of the leader of the cell-phone division to become president are particularly interesting because the directors were not especially well versed in the business. “There wasn’t a single technologist on the board,” Ollila said. There were insurance executives and bankers and directors from the old guard of Scandinavian business ownership, but no director who could have stepped forward to lead the company into the new era of technology.

Although Ollila had much more experience in the business than the directors did, he was not exactly a dyed-in-the-wool technologist either. After earning a master’s degree in political science from the University of Helsinki, a master’s in science (economics) from the London School of Economics, and a master’s in science (engineering) from Helsinki University of Technology, he had spent eight years at Citibank, holding various managerial positions within its corporate banking division. In 1986, he joined Nokia as senior vice president of finance and had only become president of Nokia cell phones in 1990. But Ollila had spent his two years learning everything he could about the design and manufacture of the product. “I went to the floor, to the factory, to the labs,” he told us. “I spent two years learning.”

Why, then, we asked Ollila, had he come to such a different conclusion than the consultants and Ericsson? Strategy making, he responded, involves not just rational analysis of markets and competitors, but also intangibles and, in particular, commitment: “Commitment determines the company’s most fundamental questions of existence and survival.” He continued, “I had an intuitive feeling, and there was a group of people whom I knew felt the same way. We saw the crisis as just pitiful mismanagement by the fifty- and sixty-year-olds—the old school.” Like Conant and Sands with their respective businesses, Ollila sensed the potential of the mobile business and was willing to commit fully to it.

Behind his belief and commitment was a deep insight into the hidden strengths of the business that the consultants had missed. Ollila explained: “There was a group of ‘youngsters’ who had been with the company for ten or twenty years, not more, and who had been attracted to the company, typically in the early 1980s. What was remarkable about this group was that they were the best and brightest.” He continued, “If the best and the brightest of one generation—in any generation, in any country—get together into one company, which happened to be Nokia, and many of them are in telecom, then there’s a feeling that, gee, we can do something really good.”

Embedded in this group’s sense of itself was a different and more powerful strategic identity for the firm. These people represented, Ollila continued, “a nucleus of know-how in the mobile phone business. It’s the cumulative knowledge of what you know when you’re first here as a twenty-year-old in 1981, when cellular networks are just being invented, and then you are a thirty-year-old in 1991. You basically are the best in the world, if you are a smart guy. You have worked all your life, done your thesis in university. There literally were hundreds of these people. It was a fantastically strong core.”

Having identified such promising potential, Ollila and his colleagues still had to unleash it. The emotions that the crisis triggered worked in their favor. Nokia’s employees, especially that brilliant band of engineers, had been seriously roiled by the period of financial distress, bad press, and the company’s near-sale to, and then maddening rejection by, Ericsson. Ollila told us that the Nokia engineers found the whole episode to be “shameful.” Their pride had been battered, and they essentially said, “We really have to prove that we can do better.” When the board of directors selected Ollila, the engineers cheered. “There was a really energizing feeling when they saw that there was somebody of their ilk becoming a CEO,” said Ollila.

Ollila fueled that energy. Within weeks of his appointment, he went public with a bold vision for the company, predicting it would soon break into the Japanese market and that its cell-phone sales would grow by 30 percent to 40 percent per year for the rest of the decade.

More significantly, Ollila and his colleagues tapped into the already powerful sense of purpose that had motivated the engineers to join Nokia and work on mobile telephony in the first place. When Ollila had stepped in as head of the mobile phone division in 1990, his first focus had been profitability. “My first two years,” he remembered, “I had to fire seven hundred fifty people. The business was not healthy.” It had lost money each of the previous three years, as it expanded, according to Ollila, from a lab of four hundred people to an industrial enterprise. But by the summer of 1991, he and his team started thinking about what the business could become. “We didn’t think about beating Motorola,” he told us. “Motorola looked too far away and too big, too smart to think about what they did. So we didn’t think about beating them. We thought about doing something significant that would have an impact and help us to grow a business.”

From the beginning, there was talk of social value. “Making an impact, changing people’s lives in how they communicate—that was always in our PowerPoint slides,” Ollila said. “We wanted to change the world.” In the spring of 1992, Nokia adopted a new theme, “Connecting People.” “We really felt good about it. It struck a chord. We were proud that we had a theme that wasn’t centering around technology,” commented Ollila.

Nokia’s theme put the mobile phone strategy in a whole new light, as both a business and a social endeavor. And it led the company’s leaders to two assumptions that were fundamentally different from those of other players in the market at the time.

The first assumption was about who would be the ultimate customer for this new thing called the cell phone and how that person would use it. The conventional industry wisdom at the time was that the cell phone would always be a premium item, a toy for business executives. Nokia, however, in keeping with its “connecting people” theme, saw the cell phone as a way for people of all kinds to connect with one another quickly and easily, wherever they were. “There was a strong element of trying to figure out where is this world going with the communication?” Ollila said. “And there was both a utilitarian aspect—productivity improvement—as well as an entertainment or lifestyle aspect.” Nokia believed that, if defined as both a practical and a lifestyle product, the phones would end up “in everybody’s pocket.” Like Microsoft’s vision of a computer on every desk, Nokia saw ubiquity and ever-declining prices for its product.

This bold, contrarian assumption led to a second one that was perhaps even bolder. The companies that saw the cell phone as an executive toy naturally assumed that their biggest markets would be those with the highest concentration of executives, which meant the United States and Europe. Nokia, however, “made an assumption that the winner in this game is not going to be decided in the U.S. or in the European market, but in the emerging markets,” Ollila told us.

By the end of 1992, despite the consultants’ earlier skeptical report, Ollila and the senior team were not leading Nokia’s people on an irrational charge, but directing them to work toward the future potential—or, as Wayne Gretzky put it, to “skate to where the puck is going to be.” They had developed an increasingly compelling strategic identity for the enterprise that connected the core engineering strengths of the organization (hands) to a meaningful purpose of connecting people that engendered emotional commitment (heart) and capitalized on a unique set of insights into the market dynamics and future sources of success (head). This strategic identity proved the basis for motivating and continuing to attract the best and the brightest, not only from Finland, but from the rest of the world as well.

Making the Strategy Emotionally Relevant

While the specifics differed for each, the other CEOs in our sample told us their own strategic stories in ways that struck many of the same notes. For example, Marjorie Scardino, CEO of Pearson, an international media company, spoke of “creating a company that would be motivating to the people working in it,” as well as “looking for a great market, and a business where they could achieve leadership positions around the world.”

Anders Dahlvig talked about making the strategy at IKEA “emotionally relevant.” What he meant, he explained, “was having some sort of social ambition as part of your business idea . . . Our vision is to create a better range of goods: we want to make sure that people who are on a budget can buy good furniture. It’s about design and function at prices low enough to make it possible even for people who are single parents to afford it.”

“Of course,” Dahlvig noted, “we have to make money on the bottom line; otherwise we couldn’t keep running the business.” IKEA had to connect the external vision to a set of distinctive internal strengths that could allow it to deliver high-quality design at low prices and still be profitable. “From the very beginning, when we started with the business idea, our entire business model meant that we did things completely differently,” he said.

For a company whose trademark is high-quality design, IKEA’s key insight was not to start with design, Dahlvig explained: “One of the secrets behind us is that, say, a table doesn’t start with a designer making a drawing of something he thinks looks good.” Instead, he noted, “there is a product range strategy behind it: What are the prices? What are the quality factors? What is the range expression? So that the finished table will suit the market.” He continued, “You need to understand the entire supply process—the materials and where they come from, how they can be used for products, and how the production process compares. We need to understand how the production process works for different kinds of material so that we can calculate what the price tag is going to be for the end-user before actually designing the product.”

Doing things differently at IKEA, however, goes far deeper than just having a well-honed, design-to-cost product development process. Dahlvig emphasized: “Our values are different. We encourage discussion. Those are our values, those are the kind of people we pick—people who question things, who like constant change and development. That is a driving force within our culture, within this system.” In turn, that culture of open discussion and questioning is nurtured and sustained by a deeper set of values and choices. The soul of IKEA, in Dahlvig’s view, “is the way we treat each other in the company, the way we are as human beings. Removing all the barriers between bosses and employees, symbolic and nonsymbolic, working in close proximity to each other. There is a sense of community, an openness between bosses and staff.”

These core elements of IKEA’s identity were already deeply rooted when Dahlvig took over in 1999. But with IKEA’s growth and development, its strategic identity also needed to evolve. In terms similar to a parent describing an adolescent child who is growing up, Dahlvig spoke of IKEA as “having been an entrepreneurial company that had grown out of its clothes. We had to go through the whole process of becoming a major company, to manage being big with all that entails. However, at the same time, we wanted to keep many of the positive features of entrepreneurship.”

In the 1970s and 1980s, IKEA went from being a Swedish company to a company with a presence in all of Europe and North America, almost twenty countries in twenty years. In essence, Dahlvig recalls, “it was a strategy of entering a country and opening a few stores, and then we would jump into the next country, instead of penetrating that market more deeply.” A consequence of the rapid expansion was that IKEA had become known as a niche player.

Dahlvig and his senior colleagues saw the need to change strategies. Instead of working toward expansion to an ever-growing number of countries, “our strategy would be to broaden our customer base in markets where we were already present and could become market leaders,” he remarked.

At first glance, this might seem a modest shift. But Dahlvig explained why it was a fundamental strategic change: “Until then, our profile had shown us being different, a company entering the market with a Swedish or Scandinavian profile, which appealed to a restricted group of customers in Germany or Britain or wherever.” People viewed Scandinavian design as something distinct, not directly addressing local mass-market tastes. To deepen IKEA’s presence, to become a market leader, “a lot of new things were demanded of us in terms of strategy: how to gain acceptance of our product range by a much broader customer base,” he said.

Getting IKEA to make this shift, Dahlvig realized, would require a deeper strategy process than its existing planning approach, one that would entail extensive involvement by people at all levels across the organization. He explained, “We began by creating a plan, which we called, ‘Ten Jobs in Ten Years.’ So you could say it was a ten-year plan. We’d never had that before. We had always worked with three-year plans and one-year plans.” But three years was too short for the transformation Dahlvig was envisioning.

The ten-year plan, which took about a year to create, “gave direction for our way forward and set various priorities and objectives,” Dahlvig said. “It took another year to start implementing it and to ensure it was anchored throughout the organization. You can’t provide the answers to all the questions with a ten-year plan; the organization must find solutions within these guidelines and ambitions. We produced action plans with a three-year perspective. And the stores have one-year plans.”

As the Nokia and IKEA stories illustrate, developing or recrafting an organization’s strategic identity is a deeper process than simply articulating a new strategy. The CEOs of these firms were deeply involved personally in an iterative, intuitive process, paying close attention to their current successes and failures, probing their organization’s character and potential sources of advantage, while often putting a wide cross-section of the organization to work on different aspects of developing strategy and ensuring alignment with it. As Ollila described it, “There’s a lot of communication, which is very direct, with lots of examples shown of what it means. In the early nineties, even with the difficulties, we had hundreds of people working on our strategy. Later we may have had a thousand or two thousand people. So you build alignment, you build engagement.”

Many of the CEOs described how extensively they traveled to engage people at all levels in redirecting the company. They emphasized, however, this was not just to build support, but a genuine opportunity for them to learn about the company and what could prevent or accelerate execution, often leading to further refinements to the strategy. They did not see engaging a cross-section of employees in strategic dialogue as a massive one-off campaign to launch a transformation, but rather as an ongoing process. As Sherrill Hudson, CEO of TECO Energy, observed, “strategy is one of those things you constantly have to upgrade.”

The picture the CEOs painted was very different from the rationally focused, often consultant-driven exercise that frequently constitutes strategy making. Instead, informed by a keen understanding of current business performance and learning from their successes and failures, they described a process of deepening insight into where the distinctive people, capabilities, and culture of their enterprise could provide advantage. As these CEOs engaged in real discussion and debate with their people, they forged a shared sense of strategic identity and meaningful purpose, one that would resonate deeply with the organization: making both money and meaning.

See Organizational Capability as Strategy

In defining the strategic transition during his tenure, Dahlvig spoke of IKEA’s shift in the marketplace from niche to mass market, and then gave equal or more emphasis to the organizational dimensions of “moving away from being a small player to becoming a big one.” He explained why this was so significant: “The individual units until then had been working independently of each other. We had extensive local freedom and a very limited central IKEA staff. We didn’t really reap those benefits of scale that spring from being a big company, because everybody was doing their own thing. We wouldn’t have been able to grow if we had continued in the same vein.”

The opportunity he saw was simultaneously unleashing the entrepreneurialism of the store managers, while also gaining the benefits of scale. That required, in his view, a mental readjustment: “Instead of being national, we were going to become global/local. What we were really doing was eliminating responsibility in the middle, at the level of the country organization, so we could lift up responsibility globally and also pull it in the direction of the local store.”

The consequences were far-reaching. The country organizations experienced a major readjustment in terms of power and activities, and ultimately reduced their head counts by 35 percent to 40 percent.

The role of the store manager expanded, with multiple consequences. “It turned out,” recalled Dahlvig, “that many store managers didn’t live up to expectations. That’s why we have increased local accountability. We have set up local boards, something we didn’t have before, so that today each store is like a company.”

The shift in power to the global functions did not significantly increase the head count at IKEA’s central office, as one might have expected. Instead, Dahlvig explained, “when we carry out development projects, it’s our principle not to hire permanent staff here at headquarters. Over the project period, we finance a number of people who return to their units on completion of the project. We pay for them while they are here, and they continue under their contract of employment in Germany or China or Russia or wherever.” There was a clear rationale behind this approach: “Your knowledge becomes obsolete fairly quickly if you become permanently employed in a dedicated function. That’s why we believe it is better to pick people to work with development projects on a temporary basis and send them back into the business afterwards.”

Other CEOs were equally focused on the strategic nature of their organizational choices. As we have seen, Peter Sands remarked on how Standard Chartered Bank’s ability to make an organizational matrix work with strong country organizations as well as strong global product businesses underpinned its success in being locally responsive yet gaining the benefits of its geographic reach. Volvo’s Leif Johansson elaborated at length on how the organization’s capacity to consolidate the number of engine platforms was the linchpin of its global truck strategy. In each case, the CEOs highlighted how their organizational strengths enabled them to bring together hard-to-combine characteristics (such as scale and entrepreneurialism, in the case of IKEA) in ways that their competitors could not match. Ollila spoke of the inextricable linkage between strategy and organization at Nokia: “Because the technology was not only a breakthrough in terms of growth potential, but disruptive in the sense that it killed some old stuff, we could actually create an exceptional company—not just a growth company, but an exceptional company.” He continued, “We did two things at the same time. We moved from a Finnish base to be a truly global company. And we moved with a breakthrough or disruptive technology.”

In retrospect, it is hard to fully appreciate the breathtaking nature of the dual challenge Nokia was taking on. In order to sell to the emerging markets, primarily in Asia, clearly the company would have to invest in building up substantial local organizations, especially in distribution, with people and a mix of cultures very different from its base of Finnish engineers. What’s more, devising a “phone for everybody” would require a very different approach to design, manufacturing, and marketing than would the toy for executives. It meant developing a phone that would work for people who live and work in jungles and fields, towns and villages, as well as in cities, suburbs, and office buildings. These considerations had implications for phone size, functionality, reliability, and cost.

The company translated the strategy into a set of guidelines for the product itself. In 1994, Ollila told us, the company defined goals that it called “100 to the power of 4.” It said that, within five years, the handset would have to weigh no more than 100 grams, be a maximum of 100 cubic centimeters in size, contain no more than 100 components, and cost no more than $100. “We were setting targets that were way off the scale, that looked really crazy, because phones were really big then,” Ollila said. “Yet, in the year 2000, six years later, we had beaten all except one.” The one missed target was the number of components, which still hovers around three hundred, although that’s half of the six hundred it contained in 1994.

The small, light, simple, and cheap phone proved immensely appealing to people around the world. “Look at our market share in China, India, Latin America, the Middle East, Africa,” Ollila said. “The deeper you go into the jungle or into the clay huts in India, the closer it is to 80 percent share.” And Ollila, typical of the CEOs in our sample, had gone into the field to see his products at work firsthand: “In a clay hut in India, I asked this guy, ‘Why do you have a Nokia phone?’ He said, ‘This is my second phone. When I bought my first one three years ago, I was told by the dealer that this is the best and I would get the best money out of it when I sell it to the next guy.’ And he was right.”

Ollila observed that it is easy to have a strategy to be more innovative than your competitors, but much harder to make it happen in practice. Innovative companies face the dilemma of how to achieve focus without heavy-handed control, how to channel innovation without killing it. Ollila talked at length about that challenge: “If you have costs to worry about, and you take an axe to the operation, that’s the end of innovation. But then again, if you have no rules, no guidelines, nothing—a lot of companies have been killed by that. Because there’s no strategy, no vision, no rules, no connection to reality. That has happened many, many times.”

Nokia, therefore, sought to create an atmosphere of what might be called organized chaos. That meant that the company would work on a number of ideas at once, but would focus on those that were advanced and seemed to have big potential as valuable intellectual property, because no one was really sure where the industry was headed. Management had to make decisions, however, about how long to keep pouring resources into any of these nascent ideas. At Nokia (and at other cell-phone companies), one of the promising projects was the speech codec, a method for compressing speech for digital transmission. Twenty engineers had worked for three years on Nokia’s speech codec, but had little to show for their efforts. The project was finally terminated, and the engineers moved to other projects that seemed more relevant and promising and that needed the help. Nokia went with a speech codec from another company.

A year later, the speech codec had become an even more central technology to mobile telephony, and Ollila began to wonder if Nokia had made the right decision to stop work on its own version. Then he got a call from an R&D manager, “who doesn’t really know whether he should be proud or totally embarrassed, saying that we had five guys who had continued the work, without any permission, because they thought that management was a bunch of fools and didn’t know what they were doing. They had come in weekends or evening time with no hours counted. And now, it seems, we have the best speech codec in the world. This is what Nokia is all about.”

This combination of pride, passion, personal commitment, and loyalty made Nokia a world leader in cell phones and a place where people who care about them wanted to work. “There’s a huge pride in the organization,” Ollila told us, “which you create with the right kind of guidance, goal setting, motivation, and treating people well—giving the right people a bonus or a promotion or a pat on the back or a bucket of beer on a Friday. It’s not about huge money bonuses. It’s these small things, as long as they are right, and as long as you praise even bad behavior. I mean bending the rules a bit (as, for example, with the speech codec), as long as it gets results for the company.”

Commit, Yet Adapt

The process of defining its strategic identity enabled Nokia and other higher-ambition companies to commit to those parts of the business portfolio that fit and defined a natural trajectory for growth. A number of higher-ambition leaders explicitly capitalized on their companies’ distinctive organizational capabilities and approach to pursue strategies as preferred acquirers—for example, Sands at SCB; David Langstaff at U.S. defense company Veridian; and Bertrand Collomb at French building materials maker Lafarge.

Clarity in strategic identity also enabled higher-ambition CEOs to exit those businesses that did not fit. As Ollila bluntly put it, having decided to focus on cell phones, “we needed to get rid of the nongrowth products—the cable, the televisions.” Yes, the company had made some attempts to pare its portfolio with the sale of parts of its rubber, paper, and electronics businesses. But many other units remained that did not fit Nokia’s new strategic identity, despite their long histories and devoted employees. Ollila did not want to sell at the bottom of the cycle, and he also did not want to create more turmoil and disruption too quickly: “People say, ‘Gee, there’s a new management!,’ and then suddenly you announce that you’re selling the cable business.” This is not good for loyalty or commitment. Ollila waited until the company had improved its performance to complete the work of paring back. Although Nokia sold its paper company in 1992, it waited until the winter of 1994 to sell its German television manufacturing business and its power unit.

But restructuring is difficult and can strain the fabric of connection and belonging these CEOs seek to develop. The sale or closing of a unit, or even the possibility of such a move, can’t be discussed publicly, so employees often learn from reports in the media that their business or group has been sold. Ollila remembered, “People came to me crying, ‘Why do you do this to me?’ Or they would turn angry and not even look at me. There was huge emotion about it, because they could see that Nokia was going to be a good story, and they wanted to be part of it.” But widespread agreement on strategic direction helped legitimize Ollila’s choices. Even in the midst of the restructuring, Nokia was one of five companies in Europe to receive special commendation for employee satisfaction.

Volvo’s Johansson had to make a particularly painful cut in the company’s portfolio. Although many have forgotten (or never knew) about Volvo’s provenance—just as Nokia’s origins as a producer of paper products and rubber boots have been lost in the mists of time—the company was founded as a subsidiary of SKF, a Swedish ball-bearing manufacturer. SKF developed its vehicle-manufacturing branch to increase demand for its products. Among those was a single-row, deep-groove ball bearing known as the volvo bearing (Latin for “I roll”), which gave a name to the new line of business. The SKF Group continues to be a major ball-bearing and lubricant manufacturer.

In 1927, Volvo produced its first car, which sold poorly. It wasn’t until it launched its first truck, the Series 1, the following year that Volvo began to take off. Today, the Volvo Group is made up of nine business units, including trucks, buses, construction equipment, and airplane technology. But since 1948, when Volvo cars became the group’s leading business for the first time, the automobiles had been the iconic heart of the business.

That’s why it was so difficult to sell the car business. Johansson explained, “We realized that if we were to manage passenger cars, and commit so many resources to passenger cars, we wouldn’t be able to manage the rest. So we were facing a choice between the rest of the group or continuing with passenger cars.”

The problem was based in engineering. In 1998, when Johansson’s team did a strategic analysis of the business, they saw that virtually every unit produced its own engines. It was “completely bonkers,” Johansson said. “Truck engines and construction equipment engines and Volvo Penta engines go together very well, and the same is true of buses.” But the passenger cars needed an entirely different type of engine. Selling the car unit would make it possible to streamline and unify engine manufacturing across the group.

So in 1999, just two years after Johansson became CEO, Volvo sold its car unit to Ford Motor Company for $6.5 billion. “Strategically, it was blindingly correct,” said Johansson. From the point of view of the human organization, the sale of the car unit still causes pain. “Emotionally,” he said, “I miss cars every single day.”

Both at Volvo and Nokia, as well as in many of the other companies in our sample, the bulk of the portfolio restructuring was completed early in the tenure of a new leadership team. In other companies, the ongoing process of adaptation led to redefinitions of what was core later in the leader’s tenure. The choice in these cases was arguably more difficult, particularly with businesses very much identified with the leader personally. Yet, what was striking about these leaders was their ability to combine commitment with a clear-eyed recognition of new strategic realities.

At BUPA, Britain’s leading private health insurer, for example, CEO Val Gooding told us about selling off the BUPA hospitals. “If I was just running the business according to my own sentiment, I couldn’t possibly do it,” she said. “I love that business. I’ve been to all the hospitals, I’ve met a lot of the staff, I spent time with them. I love those hospitals.”

For leaders who are on the frontlines, such painful decisions can hit very close to home. Gooding told us that when the decision to sell the hospitals was made, the director of human resources of the hospital business approached her. “Do you know what you said when you hired me?” the HR director asked. Gooding said no, she did not remember. “I asked, ‘Would you sell this division?’ And your answer was, ‘Not while I’m chief executive.’”

But things had changed at BUPA and in the health-care sector. Changes in government policy had eroded the benefits of combining insurance and care delivery in a single organization. Increasing opportunities for private contracting meant the hospitals could potentially expand faster if not constrained by an insurance company parent. Faced with the changed economic logic, Gooding reflected, “I’m not really paid to love things, if that’s going to distort sensible business decision making.”

Beyond decisions about portfolio, the process of forging strategic identity serves to create a powerful internal gyroscope that helps the company maintain strategic consistency and to channel innovation in the right strategic directions.

Dahlvig highlighted the value of stability and sustained commitment: “We’ve had the same business idea, the same product range for all these years, and simply developed it further. We’ve invested in communications, brand building, and it hasn’t been in vain. We’ve simply built and built and built.” The result, he noted, is that IKEA has the number-one most-recognized retailing brand in the world, despite being ranked as the thirty-fifth largest retailer by sales: “Our stability, combined with our uniqueness and the soft elements in our values—it’s those things that have made us more famous than big.”

Yet Dahlvig also emphasized that stability needs to be balanced by innovation. “One of our strong points is that we have stability in the big picture and also innovation in the detail. The framework is very stable—the business idea, the concept, the overall plan, the strategies,” he said. But, he continued, we are “extremely innovative in the way we develop things over the course of our journey.”

Ollila also described how sustained commitment was at the root of Nokia’s success, fueling multiyear investments in its distribution networks, in its product platforms, in its brand, and in its technical capabilities. As a result, in 1998, six years after putting cell phones at the center of the company’s strategy, Nokia surpassed Motorola to become the world’s largest producer of cell phones.

Ollila drew a sharp contrast with Motorola, where there were changing fashions with changing CEOs. “Look at Motorola. It’s a story of inconsistency, despite the legacy of fantastic technology. It’s a fantastic company with so many good engineers. But it’s internal tribes competing with each other, killing each other. And management is giving very mixed signals all the time,” he said. The multiple changes in direction, Ollila explained, created “fundamental problems with the software, with the operating system, with operating platform choices. They lost the ball and haven’t been able to grab it since.”

The higher-ambition CEOs were acutely aware that finding the appropriate balance between committing and adapting is a never-ending challenge. The consistency enabled by a strong strategic identity can become a liability if not refreshed when industry dynamics change, as Nokia’s experience illustrates. With nearly two decades of sustained focus, Nokia built and maintained dominant positions in the major developing economies. Yet a strategic orientation that prioritized the mass market left Nokia vulnerable to Apple’s high-end breakthrough with the smart phone. Former employees report that Nokia had a prototype handset with a touch-screen and internet compatibility as early as 2004, three years before the launch of the iPhone, but that the company saw it as too expensive to produce and did not pursue it further.1 The dramatic success of the smart phone forced Nokia onto the defensive, struggling to produce a product that could compete successfully in the most-advanced markets. Yet, even as its market share in the United States trended to low single digits, its continuing strength in the developing markets enabled it to maintain leadership in global smart-phone market share in 2010.2

As Johansson put it, it is a mistake to think a company has ever arrived at a finished state: “Companies are never finished. You can never really say, ‘now we’re done.’”

Conclusion

At the heart of higher ambition is a commitment to building a thriving and enduring human institution. The success of that institution depends on the capabilities and aspirations of the flesh-and-blood human beings who are its members.

In this context, the CEO’s role as chief strategist moves from an analytic and numbers-driven exercise to a developmental task, akin to helping individuals come into their own and redefine their identity as they make the transition from one life stage to the next—from childhood to adolescence, from adolescence to adulthood. At each of these stages, people undergo a shift in their sense of who they are, their personal identity, that is deeply rooted in their ability to successfully align passions, capabilities, and values with the opportunities the world provides. Making these transitions can be both liberating and wrenching. Holding on too tightly to a past identity (for example, the successful high school athlete who can’t acknowledge that he doesn’t have the speed required to make it in the pros) is just as destructive as not understanding one’s core strengths.

Analogously, as we have described, our CEOs engaged their people in an interactive process that resulted in a new strategic identity that linked head (a clear-eyed understanding of marketplace opportunities and challenges), hands (a distinctive core of people and capabilities), and heart (values, purpose, and passions). They then built the organizational and business capabilities required to successfully enact this identity. These strategic identities were rooted in current capabilities and embodied a sense of aspirational stretch as to what these firms could become (much as a great mentor or coach builds on and develops an athlete’s natural strengths to compete at a higher level). A well developed sense of strategic identity provided a compass for sustained investment that reinforced core strengths. Maintaining this identity, in the context of a changing market required ongoing adaptation and paring away of aspects of the firm that were no longer critical to future success.

By directly involving a wide range of people in strategic dialogues about the firm’s direction, while setting high aspirations for both business performance and social value, these leaders increase commitment and boost the energy level. By speaking both to heads and hearts, and demonstrating a willingness to listen and learn from people’s points of view concerning strategy, they earn trust, reduce friction, and build the fortitude needed to follow through on difficult choices.

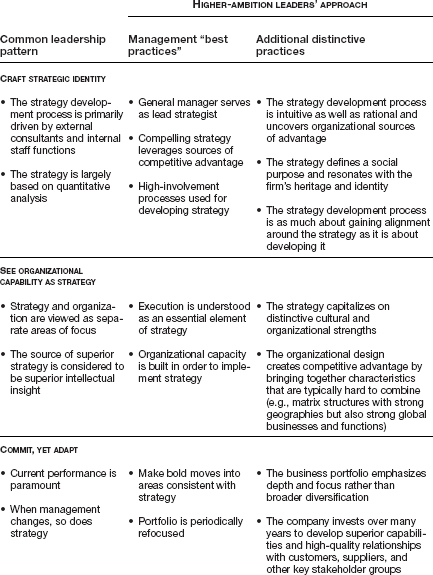

In table 3-1, we contrast the common leadership pattern with the higher-ambition leaders’ approach and summarize how, in forging strategic identity, higher-ambition leaders adopt an approach that both includes but also goes a step beyond traditional management best practices.

| TABLE 3-1 |

| Forging strategic identity |

|