CHAPTER 20 So What? What Difference Has This Made?

There are many books about principles and modes of leadership, change management and organisational design. Very few attempt to link the ideas with actual, specific outcomes. Some may make general claims of significant increases in productivity or efficiency but do not provide data. Perhaps the exceptions here are in specialist areas: the internationally recognised Dupont Workplace Safety Training programmes and modular training materials for the support and further development of safety professionals, line and operations managers and line supervisors, or in technical processes such as six sigma and in general the Continuous Improvement movement.

This is understandable at two levels. First, and most important, causality is actually difficult to attribute accurately. For example, a system change or behavioural change in one area may affect another area positively or negatively. An improvement in productive behaviour or better teamwork may coincide with improvements in technical processes or an upturn in the market. How do we separate these strands fairly? Second, change is made by people putting ideas into practice. That practice may vary – even unintentionally – or the ideas may be misunderstood, or both.

Organisations are not easily made into laboratories with experimental and control groups. People will vary in their opinions as to what caused what. In the words of an old saying, ‘success has many fathers, but failure is an orphan’. Despite these difficulties it is worth trying to ascertain what effect has occurred and whether it is attributable to the implementation of particular ideas. We look at implementation in a wide range of organisations. We examine work in the Anglican Church, schools, the public sector and diverse industries. They demonstrate that the concepts are not limited culturally nor to a sector or type of organisation, since the proposition is that they are based on fundamental principles of purposeful, human behaviour. We have applied them across the Public, Private and Not-for-Profit sectors. They all relate to creating Productive Social Cohesion.

We also have to bear in mind that not all change is measured in output alone. Qualitative measures such as personal job satisfaction, a sense of achievement and pride in work are also relevant and meaningful to members of an organisation and other stakeholders.

We have included several case studies here. Some are from the first edition as they provided the first really significant evidence of the potential of Systems Leadership and actually stood up to judicial scrutiny and were formally stated (Australian Industrial Relations Commission) to have delivered high productivity improvement. However, we have continued to see the ideas implemented in the last ten years and so have selected new case studies (more to be found on the website):

1. The implementation of Systems Leadership in the Australian Victoria State Judicial System.

2. The implementation in Mexico with regard to cross-cultural understanding and relationships that enabled a mining business to grow with mutual benefit.

3. The implementation in a state school in Far North Queensland, Australia.

4. The analysis of mental health services in Trieste in Italy.

5. The use of concepts to analyse combat in Afghanistan.

There are also other case studies; some from the previous edition and some since which can be found on the associated website www.maconsultancy.com. Also the websites Macdonald Associates, Bioss and SLDA provide other examples of the use of SLT.

The original cases were examples where the introduction of systems leadership concepts was careful and deliberate and did not coincide with technological change, where the impact was recognised not only in the organisation but also in the wider society.

Box 20.1

We encourage discussion of evidence. We look at any approach and ask three questions of all approaches including our own:

1. Does the approach go beyond the WHAT to the HOW i.e. does it describe how to create the desired culture?

2. Is it theory based: is there a set of principles and propositions that are internally consistent and predictive?

3. Is there evidence: are there examples of where this approach has worked and resulted in measurable positive change

Before examining these cases we would like to reinforce the argument that consultants do not bring about change. The leadership of the organisation brings about change. Overall a change process is a partnership between the leadership, advisers (internal and external) and the members/employees of the organisation. This is reflected in the authorship of this book. Consultants who claim to ‘change the culture’ do no such thing. If changes occur, it positively involves many people working hard over a long time. Leave the silver bullets for the vampires. The most important platform for change is a coherent, integrated set of concepts which is available to and understood by people involved in the process. This is what we have attempted to provide in this book. This will not be the product of one mind but the product of working relationships. It is imperative that the concepts are internally consistent and make sense. The first test of any articulation of process is whether it can logically be justified or falsified. It must predict its own failures.

For example, in one organisation where we worked the change process chosen was almost entirely based on the Working Together course (the dangerous ‘sheep-dip’ – the idea that all you need to do is take your people through the course without any other support or systems work). Very little structural or systemic change occurred in parallel. Unsurprisingly, very little positive change occurred and the course itself became a negative symbol only serving to expose the gap between good practice in theory and the evident poor practice in reality. Systems remained that contradicted the teaching, and the leadership handed the process to HR which, as predicted, made things worse, despite some heroic efforts from the HR team.

Although this was a failure in terms of positive outcome, it actually reinforced the conceptual framework by producing the predicted poor results. It was not, however, our proudest moment and Macdonald Associates should have had the courage to withdraw sooner given the conditions.

In another example we worked with an organisation where there was a lack of capability in several key roles in the CEO team, as defined by our capability model. There was a lack of mental processing ability (according to the definitions) and an excess of energy and the use of power. Despite the CEO acknowledging this, it was not possible at the time to remove the individuals, and the change programme faltered because it was implemented in a patchy way. This is not to say the CEO was wrong. We must work in partnership, not to a set formula. All we can do is explain and predict that, if it is not judged appropriate to make certain changes, then this will affect the outcome. As was outlined at the beginning of Part 5, there is an ideal process but conditions for an ideal process cannot be created artificially. If the process is to be modified, so should expectations.

The remainder of this chapter examines the four new case studies and then returns to the major case that established Systems Leadership as a highly successful approach and had a significant impact not only on the organisations concerned but society itself.

Case (i):Victoria State County Court Performance 2015–16

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: TOWARD COURT EXCELLENCE – PRACTICAL APPLICATION OF SYSTEMS LEADERSHIP AT THE COUNTY COURT OF VICTORIA, AUSTRALIA

This executive summary presents the context, process and outcomes of application of systems leadership at the County Court of Victoria. This work began in early 2014 and helped to inform new governance arrangements adopted by the Court in October that year. These principles and models continue to be applied especially in court administration and the performance of the court and the registry in the administration of justice continues to improve.

Context

The County Court of Victoria (the Court) is the principal trial court in Victoria, providing fair, affordable and effective access to justice for the Victorian community. The Court manages over 12,0001 matters per year. The Court’s 652 judges (plus the Chief Judge) and its operations are supported by more than 300 staff. In addition to proceedings in Melbourne, judges also hear cases at circuit courts in twelve regional centres. Judges in the Court sit in three divisions: Criminal; Common Law; and Commercial. Circuit operations form a fourth group.

Increasing demand, complexity and other challenges

Sustained increasing demand: as shown in Figure 20.1 the number of matters finalised at the Court from 2009/10 to 2014/15 has increased by 18% (10,377 in 2009/10 and 12,258 in 2014/15), a growth rate of 3.5%.

Increasing complexity of matters heard: an ongoing significant issue for the Court is the growing complexity of the law. This area continues to contribute to increased hearing time for both pre-trial hearings and the average length of a trial. The management of this area is crucial to the Court’s ability to meet its obligations to the community and to reduce the negative impact of delay on complainants and accused.

Increasing diversity of court users: there are an increasing number of individuals representing themselves in the Court and these Self-Represented Litigants (SRLs) require greater levels of support and case management. The number of SRL cases finalised in the Court has more than tripled since 2013.

Legacy IT infrastructure: a significant challenge for the Court is the redevelopment of its ageing case management system (the IT system which supports the majority of court processes).

Constrained fiscal environment: the Court operates in an increasingly constrained fiscal environment. Structural funding issues linked to the establishment of CSV need to be resolved to establish a sustainable financial base into the future.

Increasing workload on judges: from 2009/10 to 2014/15 overall judge numbers remained static at 60 (plus the Chief Judge) but the number of matters finalised per judge increased from 169.5 (2009/10) to 201.0 (2014/15).

Listen-Plan-Do: The application of Systems Leadership

Under the sponsorship of the Chief Judge, the CEO (chief court administrator) was supported by an external consultant and together they interviewed more than forty judges using Systems Leadership as the framework for questions and analysis.

The following challenges from a systems and behaviours perspective were identified:

• Purpose of the Court ‘To hear and determine matters in a fair, timely, accountable and efficient manner’ was clear but coherent systems of work were lacking as was the court administrative capability to work towards excellence using the International Framework for Court Excellence (IFCE) the Court had adopted.

• Governance arrangements needed to be established to clarify and strengthen the authorities of the Chief Judge, his ability to delegate authority for judicial administration to Division Heads and to improve the effectiveness of administrative support.

• Administration management hierarchy could be better structured to develop, improve and integrate systems of work and change in response to the new operating environment.

The CEO and a small senior team during 2014 worked closely with the judiciary, supporting the transformation of the governance arrangements for the court. These changes were endorsed by the Chief Judge unanimously accepted by the Council of Judges, the governing body of the County Court in October 2014. The capability gaps to effectively implement improvement underpinned by the principles of the IFCE were also addressed through the redesign, and new appointments to the executive team to reflect different levels of work complexity. The CEO led a programme of change that has encompassed a range of initiatives and improvements based in systems leadership. Work to date has included:

• Developing and implementing a ‘Working Together Program’ that is being progressively delivered throughout the Court (including some judges who were more involved in the administration of the Court) to build understanding and capability in SLT. More than fifty staff and managers and nine judges have so far participated in the programme. Designed specifically for the Court, this programme is delivering a tailored leadership approach, and aims to strengthen the foundation of capability, foster the desired culture of collaboration and teamwork, and support the implementation of improvements across the Court.

• Adoption of ‘team process’ as the standard and expected way of working in teams.

• Adoption of ‘task assignment’ as the standard and expected way of assigning work.

• Role clarity work using SLT principles to redesign roles including clarity of authorities in relation to line management, project management and lateral role relationships.

• Redesign of various systems of work to improve productivity and remove waste.

The redesign of governance structures, is the principle focus of this case as the work was foundational, establishing a system by which the court could be directed, managed and organised to make the ‘IFCE work’, and through improvement in systems of work, drive with purpose toward court excellence.

Outcomes and benefits

The outcome of the revised governance structure has enabled the Judiciary, Registry and Administration to work together in a system with clearer purpose, boundaries and authorities. The level of work is now appropriate to the complexity of the roles concerned in particular, the capability of the Division Heads has been engaged in order to improve court performance as well as administer justice in individual cases.

The outcomes of judges exercising their newly delegated authorities are evident in the 2014/15 measures of court performance– see Figures 20.5 and 20.8.

Clearance ratio relates the Court’s caseload to its capacity. It is the ratio of the number of outgoing matters expressed as a percentage of incoming matters. The clearance ratio is an indicator of whether or not a court is keeping up with the demands for court services in terms of its incoming caseload. The Court has increased its clearance ratio indicating it is getting through the work, meeting demand and that it has capacity to meet its time standards in the future.

The cost per case is measured by dividing the total recurrent expenditure within the court for the year by the total number of finalisations for the same period. It provides a unit measure of efficiency. From forecast to actual for 2015/16 there was a 13% reduction in Crime and an 11% reduction in Civil.

The improvements evidenced in the above measures were realised in the face of growing demand and were enabled by the redesigned governance structure.

Judge O’Neill, Head of the Common Law Division was interviewed in the August 2016 Law Institute Journal regarding innovations in the Court. For Judge O’Neill the new authorities as Division Head gave him ‘the opportunity to shake up the management of the lists that fall in his division, bringing in innovations to drive efficiencies and slash waiting times’. The effect of the innovations has cut waiting times to 6–8 months and resolution time has also shortened drastically, with 65% of judgements provided within thirty days, and 85% within ninety days. Similar efficiency drives are happening in the other divisions.

Good systems support leadership succession

One of the critical issues identified in planning was ‘What if the Chief Judge (who is a champion of this work) leaves the Court?’ The former Chief Judge was due to retire in July 2016, however, following twelve years of outstanding leadership, His Honour Michael Rozenes resigned as Chief Judge of the County Court in June 2015 as a result of illness.

This was an emotional and unsettling time for the Court. But the new governance system allowed the Court to navigate the many and complex issues that arose with the former Chief Judge leaving. A recurrent concern raised in the initial interviews with judges went from a context where ‘God knows what is going to happen when the Chief leaves … It’s terrifying’ to one where, as challenging as it was, systems were in place to sustain and reinforce change and behaviours. Specifically there was a clear hierarchy of authorities to work with to make decisions and act on the many issues that arose. In addition Division Heads monitoring and improving the delivery of court services in their respective areas.

The most telling evidence of the success of this change was in October 2015 when Chief Judge Peter Kidd was appointed to the Court. He said ‘My initial impression was that the court was functioning in a highly organised and structured manner … it was an ordered, calm but busy environment …’

Case (ii):Torex Gold – Using the Values Continua as the Cornerstone of External Relationships

FRED STANFORD, CEO TOREX GOLD

Context: I have used Systems Leadership successfully in previous roles in large mining companies that resulted in productivity improvements and better work satisfaction. Moving to a role in a start-up company was a new challenge and provided a new opportunity to use the models in a different setting.

Purpose: The purpose of this case study is to demonstrate the effective use of the Values Continua to address Critical Issues. A fuller account of the project is available on the website.

In 2009/2010, Torex Gold (Torex) raised CDN $300 million on the public markets and used the proceeds to purchase a gold development property in Guerrero State of Mexico. For Torex this purchase transformed the company from ‘shell’ status to a company with a world-class gold property that could form the basis for building a modern mining company.

That world-class asset, though well-endowed by nature, was not without its challenges. The endowment at the time of purchase was a resource estimate of over 3 million of gold ounces at excellent grades for mining by open pit methods. At 29,000 hectares, the property is large, with significant exploration potential. Together, these two qualities formed the basis for the Company’s strategy:

Increase the current resource to 5 million ounces and build our first mine. Explore the property to find a resource for a second mine, and then build that.

An asset of this quality would not have been available to such a small company if it wasn’t burdened with a few challenges as well. The foremost of such critical issues was: what if we can’t gain access to the ore-body? There had been a two-year blockade, by the local landowners, that had denied access to the previous owner of the mineral rights. The local landowners had negative mythologies about mining companies; in particular they didn’t trust them and felt that such companies were unloving and disrespectful towards them. They were also sceptical about the honesty of business leaders.

My experience is that many companies pay a great deal of attention to the Technical and Commercial Domains but underestimate the issues in the Social Domain. Although this is improving there is a need to examine this area in similar if not more detail.

As we looked at the critical issues standing in the path of executing on the strategy, it was clear that there were, as expected, many Technical and Commercial issues that needed to be sorted out, but they were quite manageable. The real uncertainty lay on the Social side, and if the company was going to truly prosper, it would be because of success in solving the social critical issues. The blockade was one such issue, but there were many others associated with integrating a modern industrial operation into an area with little industrial experience and a history that led to the mythologies mentioned above concerning those in authority who often were experienced to resort to power to get their way.

So, using System Leadership principles we designed a social operating strategy that was centred on the following objectives:

1. Create an external experience of the company such that external stakeholders want the company to succeed.

2. Create an internal experience of the company such that team members willingly give their best.

3. Create an organised workplace such that willing team members can be productive.

In the beginning, most of the focus was on creating the external experience of the company. We had very few employees and all of the important relationships were external to the company. These included communities, governments, investors, regulators and contractors. How to create productive external relationships was the key critical issue and with a blockade in place on our only asset, time was of the essence.

Fortunately, Inco Limited had provided fifteen years of experience with Systems Leadership, root cause analysis, and interest-based negotiations. It was in from these models that the essence of our external relationship strategy was drawn. First and foremost was Systems Leadership and in particular the Values Continua model. The model suggests that if you would like others to willingly follow your lead, then at the very least they need to see you as operating from the left side of the values continua. While we were not in a formal leadership role with any of these external stakeholders, the issues at hand were very complex and we were looking to have our leadership to be trusted and accepted. The principle had to be the same: we needed to tailor our actions so as to be received as on the left side of the values continua, in this culture. The tools for doing that had to be the same: management Systems, management Behaviours, and Symbols that are guided by a recognition of where dissonance with existing beliefs is required.

The Values Continua model also provides an excellent end state if one chooses to apply the rigour of root cause analysis to social conflict. Many years of observing and seeking to resolve conflicts in an industrial workplace led to variant on the model that suggests:

Unless the conflict is rooted in ideological differences, the root cause of a dispute is likely to be in a feeling of offense in one or more of the values.

Listening and probing carefully to ascertain which value or values has/have been offended, can lead to the starting point for a mutually agreeable solution. (Interest-based negotiation provides helpful skills for probing past the stated positions to uncover the misaligned value, or interest.)

The decision to ‘Get on the left side of the Values Continua and stay there’ became a guiding principle in the design of our management systems that interacted with the communities, our management behaviours, and the symbols that helped to define our position on the values continua. This involved a genuine and detailed approach to understand how the local people saw the world. We had to understand what experiences had led them to create negative mythologies and then require leadership behaviours to show that we were different. We needed to design systems that were transparent and open to scrutiny. We needed to be aware of how symbols were interpreted. We were far from perfect in staying to the left side as perceived by local people, but the leaders worked hard at it, we course corrected quickly, and the positive symbols far outweighed the negatives.

The results speak for themselves. The blockade was resolved in four meetings. We found that inconsistency in the commercial relationships between landowners was seen as unfair, so we rectified that. Our genuine, paramount concern for safety and security, demonstrated through our behaviour and systems that we did not put people second. We showed that we were not interested in short-term, apparent commercial gain. Personal contact with leaders, including myself as CEO, demonstrated our serious intent to build mutually beneficial long-term relationships. Permanent land tenure was negotiated on schedule. Environmental permits were achieved on schedule. Over a billion dollars was raised through debt and equity to build the mine and processing plant. Two villages were resettled on schedule, a task seen as almost impossible by others at the outset. Security issues were resolved with the assistance of many stakeholders. The mine and plant were built on budget and ahead of schedule. The first year of operation for the plant has just been completed, and production and cost objectives were achieved.

Looking back, it is hard to overemphasise the positive impact on our business of planning to ‘get on the left of the Values Continua and then stay there’. The key word is ‘planning’ or thinking through in advance as to how actions in the form of decisions and behaviours will be received. In so doing, we were able to tailor our communications to be effective given the listening that was available to us.

For a mining company the available listening is not always charitable. But we can be honest. By definition, what we do has an environmental impact. We have no choice about where we do it, since the mine has to be placed where the ore is. There is also a tendency for many stakeholders to perceive the gold as their gold and they only grudgingly agree to the extraction if they get a ‘fair’ share. All in all, it is a business environment that has all of the potential ingredients for social conflict.

This business environment makes mining projects increasingly complex to finance, permit, and build. In looking back at the successful build of this one, it is amazing how many people helped along the way. Many of these people were external to the company and they helped at times and in ways that we were not aware of. Without their help, it is doubtful that we would be where we are today with many stakeholders and thousands of families benefiting from the project. It is easy to look at other challenged mining projects, elsewhere in the world, and imagine the same outcome for our project.

Why did some people help when they had no personal stake in the outcome? In many cases it was as simple as people ‘doing the right thing’. They could see benefits to the stakeholders that mattered to them and through new experiences they came to trust the management team to do the right thing in balancing outcomes and managing risk. The management team had an advantage: the idea that anyone could do the ‘right thing’ was elevated from abstract concept to decision friendly clarity by the Values Continua. A comment heard at a recent mining conference sums it up – ‘If you want to do that then you have to do it the way that Torex does it.’ It turns out that ‘it’ is elegantly simple, but requires a great deal of ongoing work – Get on the left side of the Values Continua and stay there!

Case (iii):Education Queensland

CONTEXT

Malanda SS (MSS) is set in a rural community with an economy associated with the dairy industry for more than ninety years. It is located 74km south-west of Cairns, in Far North Queensland, Australia, with 335 students from Prep to Year 6. Malanda SS’ Index of Community Socio Economic Advantage (ICSEA) is 975. ICSEA values typically range from approximately 500 (representing extremely educationally disadvantaged backgrounds) to about 1,300 (representing schools with students with very educationally advantaged backgrounds). Under 1,000 is considered to be disadvantaged.

The school has had seven Principals from 2012 to 2016, due to complexities associated with a previous Principal (ongoing). Prior to my appointment, the substantive Deputy Principal (DP) for twelve years, did a pleasing job in a difficult situation as Acting Principal.

I discovered on arrival, that the school has an incredibly strong community. The Parents & Citizens’ (P&C) committee is focused and passionate about the school, and its connection to the town. The P&C President is the current P&C Area Coordinator. The President is highly active in the school, and led the community’s drive to find a replacement Principal with the capability to lead, develop and sustain school improvement.

Forty people staff the school, many of whom have served over twenty years. Of the school’s twenty teaching staff, there are four ex-teaching Principals who have the knowledge and understanding of the complexity of the work required to lead a small school and are happy to assist. There are three graduates and the total teaching staff comprises four levels of teacher classification. However, how and to whom they were accountable was unclear. The teaching capability of the teachers was also unclear when I arrived.

I found that the school’s Teacher Aides (TA), like the teachers, were dedicated but their work was not clear when I arrived, and a lot of their work was channelled at a minor percentage of the student body.

The Business Services Manager (BSM) role was left vacant in the final week of 2015 due to ill health, which left the school without a person in this critical administrative role for much of the first term. When I sourced someone suitable for the role, she was still attached to a previous school, and operated in both for many weeks. There were constant issues with her access to the MSS computer network as the EQ system continually locked her out. She lost at least five days unable to access the Education Queensland network.

MSS had very little exposure to Systems Leadership (SL) modelling until the commencement of the 2016 school year when I arrived. I discovered that a benefit to our school was the nearby Malanda State High School’s (MSHS) long engagement with the modelling, and its application, in all areas of the school’s operation. I have no doubt that this long engagement contributed to the successful transition of MSHS in 2016, from the previous Principal to the current incumbent, as that school continues to flourish academically and culturally. I identified some of the systems in place in MSHS, which I thought would benefit us at MSS with minor modifications: enrolment, attendance, IT, innovation via Agriculture Science and student transition, and commenced planning their adoption and implementation in MSS.

Systems Leadership modelling’s impact on me has been significant since 2010 when I was first exposed to the material. Life before SLT was hectic, less fulfilling, leaving me feeling overwhelmed regularly, and frustrated with the lack of results and slow progress of projects. I felt like I was letting everyone down. My work wasn’t well planned, was reactive and was at times little more than ‘event management’. It affected me personally too, as the stress remained with me outside work. Perhaps the greatest epiphany came in the form of learning how to divide my work into ‘improving’ and ‘sustaining’, and the scheduling of such tasks which followed has left me in a position where I feel highly effective, and running an organisation which benefits from this. I have now applied this knowledge to other areas of my life, which has been highly beneficial and I’m a better person for it.

Needless to say, my new role provided an excellent opportunity for me to establish a culture where the modelling is not only valued, but is welcomed by staff who have experienced feelings of uncertainty about the work of their roles, and the confusion which spreads to the teams in the absence of consistent high-quality leadership.

PURPOSE

This case study briefly explains my application of SLT material at Malanda SS to demonstrate rapid progress in creating our desired culture.

METHODOLOGY

As Principal, I applied Systems Leadership material in the following ways.

• Improving clarity through the accurate identification of ‘What is the work?’ in the social, technical and commercial domains of the organisation with an emphasis on the social and technical components.

• Engaging with the Systems Leadership consultant has been of great value re advice about the practical application of the concepts, models and tools to do my work.

• Analysing and revising what was in place, e.g. the Annual Improvement Plan (AIP), resulting in a reduction in the improvement focus from seventeen initiatives to five.

• Identifying and addressing the Critical Issues by:

○ Applying the Tools of Leadership model.

○ Identifying the existing culture by:

▪ Analysing and or revising; Teacher Expectations, Classroom Practice, Explicit Teaching.

▪ Conducting a detailed analysis of staff mythologies and data to identify an accurate baseline from which we can all move forward.

○ My behaviours have been/are instrumental in the successful culture change at MSS:

▪ From the first meeting on the Pupil Free Days, I introduced the Team Leadership and Team Membership Steps and Traps, the Values Continua and our own agreed Staff Meeting Protocols (Be Safe, Be Respectful, Be a Learner) – Behaving in this manner is not just for students.

▪ The greetings I use in the mornings and afternoons – Scheduled time in my calendar daily.

▪ I visited/visit the staffroom most days at 11 a.m. – as scheduled. This is an accountability of my leadership team members also described in their Specific Role Description’s.

▪ Modelling the Team Leader behaviours/steps – and referring Team Members to behaviours/steps at every meeting/when redirection is required.

○ Implementing key systems – Systems Drive Behaviour:

▪ Organisation Chart – Clarifying Authorities.

▪ Accurate Specific Role Descriptions – Clarifying Authority and Accountability.

▪ Annual Action Plans – demystifying the work.

○ Symbols – symbols are my favourite tool.

• Assigning tasks using the Task Assignment model.

• Creating new mythologies.

• Analysis of the technical component and subsequent clarification of the work to be focused on.

• The Right People in the Right Roles Doing the Right Work – reflected in the allocation of resources.

• Designing essential systems using the 20 Questions.

○ Reading system, Daily Writing system, Students Educationally At Risk system.

• The P&C President and I work continually. We meet in the early hours of the morning which suits his business operations.

RESULTS

Some of the results I have seen as Principal include:

• Excellent productive working relationship with the Parents and Community Committee President. Together we are applying SL material to our P&C organisation.

• The creation of new mythologies with leadership team members – Staff in leadership team experiencing greater clarity in the work of their roles; weekly reporting indicating significant progress; Team Leadership and Membership steps evident in interaction between team, and respect for delegated ‘authority’ to complete work; my leadership by attending staffroom at 11 a.m. each day to interact with teaching team.

• Delivering on the SL Principle of: the right people in the right roles doing the right work.

• More productivity – progress is highly evident in all areas of the L/Ship team’s specific roles – evidenced through rapid transformation of areas relating to the AIP.

• Productive new systems:

a. Staff have a universal language to apply when engaging in discourse about the social component of their work.

b. Leadership Team members have engaged with the Task Assignment model, and completed some pleasing work as a result.

‘As a Classroom Teacher under Mark’s leadership, the school is much calmer because we know the support is there … He has worked with us to design and implement whole school systems like School Wide Positive Behaviour Learning (SWPBL), Sound Waves, Guided Reading and Daily Writing Consolidation systems … With this calmness comes self-assurance for the staff, because we are valued as an individual who is part of a team, creating a network, a community among the school staff … We are comfortable because there is no ‘in crowd’ and no ‘out crowd’. Everyone is different, but in this culture difference is respected and our tasks are done more efficiently and effectively … We are able to put forward ideas from our role and know they are considered.’

Writing system

As Head of Curriculum, focusing on the development of a writing system, the application of SLT to my work in 2016, enabled me to operate at a high level of detail effectively for the first time, successfully using social process; to have teachers know the key issues and together develop a targeted response, one where they were the key players. From the first time the data yelled at us to do something, it was thoroughly analysed and planned in detail from the start. It meant that I was able to use knowledge I had been storing away to choose the right people for the right work. I was able to use their skills and their standing in the school to influence the staff in a positive way. Building this effective writing system, easily provided the methodology to maintain and improve it and when I went on leave it was easily transferrable to my replacement. The SLT process I had worked through meant that I had made a sustainable system; a system that is powered by the teachers and is supported by the other systems in the school.

Reading system

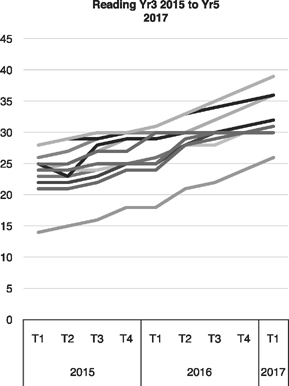

The student data above demonstrates the reading systems consistency of purpose and practice, delivering continual, more consistent improvement of reading results in 2016 and 2017 regardless of these students ethnicity, socio-economic status and minor intellectual or behaviour disorders.

As Lead Teacher use of SLT has facilitated ownership of the reading system by all involved through the effective application of social process … The efficient, successful reading system design has delivered:

• clear understanding of authority and accountability, scripted well-resourced systems, effective training, clear expectations and timelines with accurate data collection.

• a change of the teacher aides role from that of simply reading with students to working at a para professional level – efficient programme delivery, improved skill and knowledge capability and involvement in system innovations.

• analysis of recordable data allowing individual student’s achievements to be monitored and alterations made to the system, if necessary, to ensure continual reading growth.

• creating reading goals with students and informing stakeholders of progress has effectively motivated all involved.

• The work of my role as TA team leader and custodian of the reading system, listening to employee’s suggestions, ensuring timelines are met, quality assuring the results, continually identifying and implementing innovations is necessary for success.

• This ‘relative writing gain’ of the MSS students from year 3–5 is demonstrating performance significantly above the ‘average gain’ of Queensland schools – as a direct result of the Daily Writing Consolidation system, which was implemented in 2015.

SUMMARY: LESSONS LEARNED

The application of the SLT material facilitates identification of ‘what is the work’ and how as Principal, I can get my work done efficiently, effectively making rapid continual progress as my team becomes more proficient with the material and its application.

Mark Allen, Principal. 30/7/2017

Case (iv):Contrasting Symbols in In-Patient Psychiatric settings in Italy and the UK

Senior leaders from a mental health service in the UK went on a study visit to Trieste to see what could be learned from their services. Mental Health services in Trieste, Italy have become well known for their non-restrictive systems in mental health care. For example, they have no locked wards, no low secure units and use sectioning under their equivalent of the Mental Health Act very rarely. Their ward environments appear less institutionalised than those found in the UK and patients are referred to as ‘guests’. Their in-patient suicide rates are markedly lower.

Historically the Trieste services were more institutionalised than their UK equivalents in the early 1970s with more psychiatric beds per head of population. It was the leadership of the psychiatrist Franco Basaglia that made their transition to their current success possible. He defined the work of the organisation as primarily to engage and work with the people it served, rather than to control behaviour according to a set of restrictive rules that assume people will behave badly or unsafely. This created a systems change, with the focus of treatment being on the individual and what they might want or need, and the focus for staff behaviour being how they might go about engaging individuals with the service they had to offer. There was a greater willingness to tolerate uncertainty and risk (and one would assume a less punitive response to adverse incidents when they happened). Thus people were trusted and treated with respect.

In the UK, a common response to in-patient suicide has been to improve ‘environmental safety’ – to remove any potential environmental feature that could facilitate a suicide attempt. This has mainly focused on the removal of ligature points – anything that can be used for securing a ligature to facilitate a suicide attempt through hanging and has required significant financial investment.

On visiting one of the in-patient wards in Trieste, we were struck by the extensive presence of ligature points throughout the ward environment. In the UK, ligature-free taps, showerheads and door handles all have a distinctive downward sloping design. In the wards in Trieste, the fixtures and fittings were all more consistent with those found in a home environment. This more homely atmosphere was heightened by attractive furniture, pictures and curtains, and in combination more akin to a hotel environment.

In trying to understand the better performance of the service in Trieste in relation to in-patient suicide, it seems possible that one factor may be the prevalence of ligature-free fixtures and fittings. In the UK service the resulting rather clinical and institutional environment may serve to symbolically communicate the message: ‘You are very unwell, and such a danger to yourself that you cannot be trusted even with a normal door handle or tap.’ This could contribute to someone’s sense of fear and hopelessness about their experience of mental illness. We know that in many health conditions, not just mental illness, hope is positively correlated with recovery, and it may be that this powerful symbol denoting an unintended organisational mythology of hopelessness may be actively contributing to poorer outcomes.

Thus we can see that in Trieste the combination of leadership Behaviour (Basaglia) the introduction of new Systems (treatment and environment) and the positive use of Symbols (ligature points) have all contributed to a lowering of suicide rates and the general positive identity of ‘guests’ as they address their mental health issues.

Benna Waites: Consultant Clinical Psychologist

Case (v): ‘Leadership in Combat’

LIEUTENANT COLONEL TOM DE LA RUE AAC (BRITISH ARMY)

COMMANDING OFFICER OF AN APACHE ATTACK HELICOPTER REGIMENT

The purpose of this vignette is to demonstrate in a small way that the facets of ‘Systems Leadership Theory’ are alive and well in high functioning (military) organisations.

Helmand Province, Afghanistan

A Taliban stronghold had built up one summer at the height of the Afghan campaign at a place called Kunjak Hill just south of the infamous district centre of Sangin on the Helmand River. The enclave was situated on top of a hill complex with commanding views over the river flood plain and the all-important main supply route (611) from Lashkar Gar and Geresk (both forming the central Helmand economic development zone) through Sangin to the towns of Musa Qaleh and Kajaki to the north.

To neutralise the inherent threat posed to this critical supply route, an International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) Brigade plan was put together to conduct an Infantry company group assault onto the strategic position at first light one day that summer. Those taking part in the operation were gathered, the orders for the aviation assault were delivered in secrecy – covering the aviation part of the assault and the associated ground manoeuvre operation – and the force then readied itself by conducting final preparations and essential mission rehearsals. Every detail had been considered, contingency plans were in place to mitigate against potential risks and threats, and final assurances were delivered to senior commanders (accountable for achieving operational success) so that ‘launch approval’ could be granted for the mission.

At this point it is important to note that the aviation part of the assault was to be commanded by an Apache Air Mission Commander (AMC) – a combat seasoned British Army Apache Aircraft Commander with considerable operational flying experience, capable of dealing with complexity, uncertainty and change, and making fine judgements and effective decisions in dynamic and difficult fighting conditions. AMCs were usually highly qualified Army Air Corps Captains (Flight Commanders, sometimes as young as 29 years of age) and Majors (Squadron Commanders) or Lieutenant Colonels (Regimental Commanding Officers) who had reached the pinnacle of flying excellence and unequivocally proven themselves operationally on previous tours of Afghanistan.

Some essential additional context regarding what was expected of AMCs – they held ‘mission abort’ authority during operations (meaning that as the on-scene commanders they alone decided if/when any mission abort criteria had been achieved); were ultimately accountable for the safe infiltration of the assault force onto the ground; for providing command, control and protection capabilities from the air when the assault force was tactically deployed, and for exfiltrating the force once the mission had been achieved. Of note, the ground force elements were often numerous (up to Battalion strength of circa 600 officers and soldiers) and could cover many kilometres as they spread out across the terrain in tactical formation.

Consequently, the analysis, judgements, decisions and actions associated with the role of AMC were very significant indeed, often requiring decisive outcomes to be achieved in dire tactical circumstances, in situations where friendly forces were perhaps pinned down by strong enemy resistance, often at night, having sustained numerous life-threatening casualties; where the distinction between friendly, civilian and enemy was not clear; where radio communications with the ground forces was perhaps intermittent and at times charged with desperation; where contingency plans were potentially not going as well as had been planned or expected; emergency extraction landing sites for the casualty evacuation aircraft were under fire; poor weather prevailed, including terrible dust storms with dramatically reduced visibility (sometimes down to 100 metres or less for prolonged periods of times); where some aircraft had either sustained battle damage or had for other reasons experienced significant mechanical problems necessitating a pull on scarce coalition reserves … The list is endless.

In these circumstances, AMCs were required to consistently make effective decisions; clearly articulate the actions to be carried out (i.e. the work); overcome obstacles in the way of achieving mission success, by day and night for months on end, and in the face of considerable long-term fatigue; efficiently manoeuvre aviation assets around the battlefield; adhere absolutely to the Law of Armed Conflict (LOAC) and the Rules of Engagement (ROE) and, in context, deliver accurate and lethal fire onto identified enemy targets, ensuring each time that civilian casualties and damage to civil infrastructure had been avoided. The latter was something which took considerable moral courage to get right every time, particularly when under intense pressure from ground commanders in need of urgent fire support to deploy offensive weapons. Importantly, AMCs knew that they would be fairly held to account for their decisions and actions, but were content that with appropriate structures and authorities and sufficient resources in place, they had been set up for success.

Returning now to this particular operation. The attack was launched from Camp Bastion at 0430 hours and was made up of British Chinook heavy lift helicopters with the Light Infantry assault force aboard; British Apache Attack Helicopters to provide critical command, control and close combat attack (CCA) to the troops on the ground, and an assortment of supporting air and unmanned air vehicles (UAV drones), including British Tornado, US F–18 and A–10 Warthog ground attack jets, US ‘B’ class bombers, AC–130 Hercules gunships, Predator and Reaper drones, U2 spy planes and a range of other multinational coalition aircraft on station to support if needed, not least the British Chinook Medical Emergency Response Team (MERT) and US Pedro HH–60G combat rescue aircraft at immediate notice to move.

Interestingly, all of these air and aviation assets were commanded by the Apache AMC whilst the assault force was in the air. Once on the ground, the AMC and Infantry commander worked very closely to ensure that the aircraft were employed efficiently and effectively (much of this was achieved through a qualified Joint Terminal Air Controller (JTAC) who stood shoulder to shoulder with the Infantry commander during any deployment). For some of the larger operations it would not have been unusual for the AMC to direct upwards of thirty aircraft during a mission, stacked and de-conflicted in the air up to 70,000 feet in altitude, whilst maintaining a command and control link with the ground commander to ensure that the latter’s tactical intent was consistently met (i.e. that the same set of mission success criteria were clearly understood by both parties as they worked seamlessly together to achieve a ‘unified’ outcome).

The infiltration of the assault force was conducted just before first light, into fields to the west and south of Kunjak Hill and overlooked by enemy positions. The heavy lift aircraft quickly extracted into the western desert, leaving the supporting air and aviation assets overhead to provide command and control, surveillance, target acquisition and direct fire as the situation dictated.

The Infantry platoons egressed from the HLSs as soon as they were comfortable that any in-situ improvised explosive device (IED) threat had been neutralised in the immediate vicinity of the HLSs. At that moment ‘ICOM chatter’ (referring to the insecure hand-held radio communications traffic between Taliban commanders) intercepted by our airborne electronic signals scanning capabilities indicated that the Taliban were rapidly moving their forces into position.

The fighting on the ground over the next few hours slowed the assault force to the extent that their planned HLS extraction time of 0830 hours was put at considerable risk. This became a real concern for the AMC because the operation had been geared around the military tasks to be achieved on the hill, the anticipated enemy resistance expected, and the associated intelligence which suggested that the threat to the Chinook aviation extraction aircraft would rise significantly after that time. Unfortunately, the terrain proved more hostile and difficult to traverse, the IED threat much greater than had been expected, and the insurgent positions in the fortified compounds more difficult to overcome.

As a consequence, the Infantry company commander on the ground notified the AMC that the assault force would not be able to relocate to the HLSs for an extraction at 0830 hours and requested a delay, initially out to 0930 hours, then 1100 hours. More dynamic AMC tactical planning was required and ongoing fuel and ammunition sustainment of the aircraft needed to be quickly resolved – against a backdrop of relentless insurgent activity on the hill which necessitated regular engagements with the enemy and a number of aviation MERT casualty evacuations.

The battle became more intense just at the time the assault force finally began its withdrawal to the extraction HLSs. To make matters worse, further casualties were taken by the assault company as they re-positioned which only heightened the sense of urgency to extract them – unsurprisingly, this pressure was felt directly by the AMC.

The Chinooks amassed at very low level in the desert to the west of Kunjak Hill (to dramatically reduce their audible signature), and awaited the AMC’s order to ingress. The AMC calculated that the Chinooks had sufficient fuel to make one attempt at the extraction, followed by the journey back to Camp Bastion, with a maximum of five further minutes of loiter fuel. AMC direction to the Chinooks to ingress was duly given, confirming at the time that they were ‘cleared in’, but that the HLSs were ‘HOT’ (i.e. in contact with the enemy).

The Apaches and supporting ‘air fires’ platforms stepped up their engagements of identified enemy targets in the hope of suppressing them to buy sufficient time for the extraction to be completed successfully. However, at the moment the first aircraft touched down, enemy fire erupted onto the various HLSs. The northern-most landing site experienced the most hostile enemy reaction, with PKM machine gun fire and rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs) saturating the airspace and ground around the static aircraft. An immediate ‘abort’ was called by the AMC who directed the Chinooks back out into the desert to check for battle damage and await further orders.

Knowing that the Chinooks and several Apaches were rapidly becoming fuel critical, the AMC decided to undertake a second extraction attempt given that if the aircraft did return to base having not extracted the assault force, the latter would have been stuck on the ground until the following morning which would have been disastrous for them.

The Chinooks were called back in at low level with Apaches flying ‘on their wing’ firing their 30mm cannons to draw Taliban fire away from the vulnerable Chinooks onto the supporting gunships. The aircraft again touched down on their respective HLSs which, by this point, had wisely been moved to fields slightly further south (away from the Taliban threats to the north). They again took incoming enemy fire but this time remained on the ground whilst frenzied Infantry activity ensued as soldiers and explosives search dogs clambered onto the various aircraft.

The strategic fear during any operation of this nature was that an aircraft would be destroyed on one of the HLSs or, worse still, shot down just after lift-off with forty laden soldiers on board. The reality on this occasion was that although several of the aircraft sustained battle damage (which incidentally increased the complexity of the cockpit work of their respective crews), they all returned under the direction of the AMC to Camp Bastion where the aircraft were rapidly checked and serviced for further deployments, and the crews swapped to allow the next phase of operations to commence. This was also the moment for the AMC to lead his post-mission debrief, and for the Apache crews to conduct a comprehensive review of their recorded gun tape to ensure that all engagements had been carried out in accordance with the LOAC and ROE.

Postscript

It is now appropriate to take a step back from this particular operation to consider how human performance can be maximised in a more generic sense. Achieving success through human endeavour in the face of significant adversity or uncertainty is invariably difficult and, ultimately, hard-won. It is not something that can be left to chance; rather, it must be carefully planned and diligently executed (by capable and accountable individuals) from start to finish.

In this context, it should be obvious to the reader how this material relates to Systems Leadership Theory, but it is still worth highlighting a number of common themes which the theory champions and which are also proven characteristics of capable organisations – in this case, the military.

In outline, this vignette demonstrates how individuals and teams working in a productive culture can rise to any challenge if the conditions are favourable (i.e., deliberately designed and predicted to be so).

In this operation, the aviators and soldiers were extremely well trained, had an intimate understanding of the purpose and nature of their work (including the associated opportunities, risks and threats), were clear about the organisation structure within which they resided and knew that the structure genuinely reflected the work to be done.

They also had well-thought through and appropriately delegated requisite authorities and defined accountabilities; were fairly held to account for delivery and, in turn, were able to fairly hold their own subordinates (team members) to account.

They acknowledged that the military was broadly meritocratic and that capable and fully tested individuals were therefore in role and could be trusted to perform effectively in any situation, no matter how challenging, complex or uncertain – in many cases, lives literally depended upon this requirement.

They operated within appropriate work management and people systems specifically designed to free them up (unconstrained) to work to their full potential.

They were governed by effective leaders who were clear about ‘purpose’, thoughtful, decisive and committed to seeing things through ‘to the finish’, whose behaviour was exemplary and who absolutely led by example. They also resided within a team framework where the full potential of the collective was championed, each member playing a full part in planning for and delivering specified outcomes.

All of this was carried out in a task orientated working environment where task assignments were clear, resources were matched to the tasks, and contingency plans were in place to mitigate against the specified risks and threats, thereby ensuring that specified objectives could be achieved.

Finally, they existed in a defined and productive culture where good performance was rewarded differentially and the consequences of poor performance were fairly and consistently upheld (the latter requiring considerable moral courage on the part of leaders).

On this last point, it is of course acknowledged that organisations (i.e., the people employed within them) do fall short of expectation from time to time, and that military organisations are no exception to the rule. However, the default aspiration should always be to set the ‘professional bar’ at an appropriate and achievable level of excellence and, through all of the ‘people levers’ outlined in the paragraphs above, to maintain this bar as high as realistically possible to ensure that people productivity in the pursuit of defined objectives is maximised (commercial or otherwise).

Finally, it is important to note that this particular vignette merely portrayed a day in the life of a British Army Apache AMC. The reality was that these well-trained soldiers were required to perform to the highest of professional military standards, often at the same tempo, for months on end. By the end of the Afghanistan campaign in late 2014, some AMCs had completed as many as five or six tours of Helmand Province, each lasting four to five months. At an individual level this clearly represented an incredible investment of time, focus and energy by these eminently capable people. However, at a more strategic level, this vignette demonstrates the critical interdependence that exists between organisation structure, capability and leadership when it comes to driving effective work performance in demanding circumstances on an enduring basis.

The final cases below have been the subject of television programmes, business magazine articles, newspaper columns and books. It could easily be a book or books in itself. We do not intend to explore all the potential issues. The industrial relations aspect has been well documented in Terry Ludeke’s book A Line in the Sand (1996). The transcripts of the Australian Industrial Relations Commission (AIRC) case are available publicly. We concentrate here on the relationship between the systems changes and specific outcomes, with the intention of demonstrating a clear link between the two. We also do so because almost all of the material presented here was also presented to the AIRC and accepted as evidence. In other words, this data has literally been exposed to detailed, public examination and found to be valid.

The case studies concern a major change within two companies that were part of CRA in Australia during the 1990s. The companies, Comalco and Hamersley Iron, embarked on a major change programme which eventually led to almost the entire workforce choosing to change their terms of employment, a change that many said could not happen whether or not they were personally in agreement with it in principle. This was generally described as a move to ‘all staff’ conditions or ‘individual contracts’ for those in operator or tradesperson roles. Hamersley Iron was a major iron ore mining and rail operation in the Pilbara area of North Western Australia. Comalco was an aluminium mining and smelting operation with sites in Queensland, Tasmania and New Zealand. While much public attention has been paid to the eventual contractual change, the leadership of those organisations did not see the contractual change as the sole purpose. The contractual change was the outcome of a much more detailed plan of action implemented in order to improve the leadership and systems of the organisation which used systems leadership concepts to bring about change. In direct terms, a person’s behaviour does not change because they sign a piece of paper; it changes because the leadership and systems have changed.

Comalco

Comalco’s smelting business unit consisted of three major aluminium smelters: one in New Zealand (New Zealand Aluminium Smelting or NZAS), one in Tasmania (Bell Bay) and one in Queensland (Boyne Island). The NZAS story is told in detail in the case study reproduced on the website. In more general terms Karl Stewart became managing director of Comalco Smelting in 1987. In his previous roles as head of an organisational development team and vice president – organisational effectiveness, he had been concerned about the quality of leadership and the negative effect of certain systems. Prior to these roles he had spent fifteen years in line management roles, the last four of which were as General Manager of Comalco’s bauxite mine. He was acutely aware of the predominant ‘them and us’ division in employment and specifically linked this to the nature of employment systems.

In effect, Comalco Smelting, like many other traditional industries, appeared to be two parallel organisations: one a ‘staff’ organisation largely attempting to function as a meritocracy with at least some systems of performance management and pay for performance; the other an ‘award’ organisation, of ‘workers’, hourly paid, with a range of role bands, negotiated systems of pay, attendance and overtime. Of course, this is the old ‘white collar/blue collar’ distinction, a distinction which was simply assumed by most people in leadership and HR roles as if it was some sort of natural order. Essentially the staff were ‘management’ and primarily identified with the company while the ‘hourly’ employees were the ‘workers’ and primarily identified with the union. This was the case right across Comalco, Hamersley and most mining and heavy industry sites in Australia and many other countries.

What was also apparent was that behaviour was very different between the two groups. Two very obvious and symbolic differences were sick leave and time management. In an article in the Business Review Weekly (BRW) (BRW, 31/1/1994) Stewart said, ‘the difference between staff and award workers in terms of sick leave is a ratio of one to ten. In other words for every one day of sick leave taken by staff, award workers take ten.’ With regard to time management staff generally did not watch the clock and had no punch-clocks (clocking in and out). Workers (under the award) left exactly on time and felt they were ‘paid for time, not work’. This was also demonstrated by the very existence of overtime for one group but not the other.

This may seem obvious and is easy to describe; addressing it, however, is not merely a question of putting everyone on salary. How the fundamental supporting systems of this structure are addressed, identified, redesigned and implemented is crucial. The work was done over the three years that preceded the change with major emphasis on improving the quality of the leadership, poor performers in leadership roles were dismissed. In the lead-up to the offer of staff employment being made the entire management team of the NZAS smelter met in Christchurch for several days of intense work. In two days every system was examined in terms of whether it was and should be a system of equalisation or differentiation.

Following this planning period, the work was done to change those systems and symbols that had been identified as needing change. This was not particularly time consuming because over the previous three years a lot of work has been done to improve the systems that applied to the staff workforce. After the event it was interesting to find out (through confidential interview and audit) the comments made by operators and tradespeople. These concentrated upon the more symbolic systems to test whether the company was serious. As a result ‘all staff’ was tested not simply by the salary system and terms of employment being equalised, but by systems such as the ‘staff Christmas party’. Would it now be open to all? The answer was ‘yes’ – with significant success. The availability of ‘biscuits’ with coffee and ‘beer and cheese’ staff briefings were seen as a much more crucial test than even equalising the sick leave system. Car parking, transport, uniforms, canteen facilities and bathroom facilities were others that were carefully watched by those deciding firstly whether to move to staff and whether it really meant they would be ‘staff’.

Preparation was meticulous and detailed, using the systems leadership training concepts. Information about change was given to all on an individual basis by their manager-once-removed (M+1). Leaders were assessed as to their capability and removed from role if not up to the new role. As Stewart said in the BRW article, ‘You can’t expect the troops to take any notice of improved work performance if they have evidence of poor management.’

The Working Together courses were introduced to teach the new requirements of teamwork, rather than command and control. Eventually the entire workforce went through this programme. The Working Together courses helped in these specific ways:

• They clarified work expectations with regard to leadership and teamwork.

• They introduced a common language to help in work and communication.

• They built mythologies and a culture based on a shared experience as the course provided stories of success and disasters with rafts, ropes and planks.

So was all this preparation and planning worth it? First, there was a clear measure in simply the number of people who chose to remain with the organisation and to move to staff contracts: 98%. The figures for all of the Comalco plants were not ends in themselves but indicative of a coherent approach, message and leadership. Indeed all the Comalco smelters and Hamersley Iron reached figures in excess of 97%.

It is interesting when considering these figures that the AIRC found specifically that there had been no element of coercion. This can be compared with other organisations that thought they would ‘do the same’ and only offered the contract with some cash. These operations were fortunate if many more than 50% signed. However signing a contract is not an end in itself. What benefits did it produce? The run charts (Figures 20.1 and 20.2) were submitted and accepted as evidence by the AIRC.

Box 20.2 Comalco Smelters

Tiwai Point (NZAS): 1991–1998

• 30% reduction in hours worked per tonne of saleable material

• Permanent 20% workforce reduction

• Controllable costs down 10%

• High purity metal yield doubled

• Smelter expansion

Bell Bay: 1990–2000

• Absenteeism halved

• Current efficiency up 1.5%

• Workforce 1,500 to 600 over 10 years

• Tonnes per annum 122,000 to 150,000

• Technology change only to reduce physical effort

Boyne Smelters Limited: 1995–2000

• Increase in production from 210 to 350 tonnes/employee at Levels I and II

• Employment 1,300 to 774

These examples of output improvement are clearly linked to the change in leadership and systems. It should be clearly evident when that change occurred. All the graphs show significant change in September 1991 with preparation activity before that. It is interesting to note that the revenue to the smelter from the sale of the additional high purity metal (Figure 20.3) was greater than the cost reduction brought about by having fewer employees.

These changes caused a great deal of debate about the nature of the process, especially whether it was ‘anti-union’. This is largely a distraction, even recognising the political significance. The approach was to improve leadership behaviour, appropriately redesign systems and manage symbols including understanding the symbolic significance of specific changes. The purpose was to improve business performance by realising the capability of the workforce.

Some months later, however, random interviews were conducted by external consultants about the effect of the changes on work experience. What was evident was the improvement of the work experience itself. Working around furnaces all day is not, for most, an intrinsically satisfying experience, but people reported a step change in the quality of their working lives. Examples included feedback that proved to the operators that they were listened to; they also appreciated that they could use their discretion more and understood the context better. In addition, many reported an improvement in their home life: ‘I don’t just go home and open the fridge for a beer, I’m spending more time with my children even helping them with homework’ (cell-room operator) ‘I can’t wait to show my kids where I work, I never thought I’d say that, I have real pride in my work now’ (tradesman electrician). These were not isolated examples.

Figure 20.7 New Zealand Aluminium Smelters Overtime Hours Paid (%)

Figure 20.8 New Zealand Aluminium Smelters Off-Specification Metal (%)

Figure 20.9 Comalco Aluminium (Bell Bay) Limited Overtime Hours Paid (%)

Figure 20.10 Comalco Aluminium (Bell Bay) Limited Metal Products – Hours Worked / Saleable Tonne

Figure 20.11 Boyne Smelters Limited Hours Worked / Saleable Tonne

The process was applied at the other two smelters with similar results, as shown in Figures 20.4 to 20.12.

Many of these run charts are not directly related to the ‘people’ systems. They are deliberately chosen to show the effect that changes in leadership and systems can have on operational technical processes.

The overall analysis of Comalco Smelters is summarised in the chart reproduced as Box 20.1, and which was prepared independently.

Hamersley Iron

A full account of this process is contained in a paper by Joel Barolsky (1994) of the Graduate School of Management, University of Melbourne.

The Western Australian iron ore industry was characterised by industrial disputes in the 1980s – see Figure 20.8, which documents the dramatic effect after the change processes were implemented.

In June 1991 Terry Palmer was appointed managing director of Hamersley’s operations. He saw the need for change and articulated it as follows:

The 1980s had been a period of ‘winning back the farm’. We wanted to restore management’s right to manage and, to a large extent, we were very successful in realising this goal. Through this process, however, we in some ways encouraged the development of a very directive management style; we reinforced the ‘us and them’ and basically gave the unions a reason to exist. It became apparent that we had gone about as far as we should down that path. If Hamersley wanted to realise its full potential and become a truly great company, management had to effect a dramatic change in the culture of the organisation. We had to bring everyone on board; playing for the same team and by the same rules; all working together. The planning process was started so as to articulate and document this new vision for the company and to develop a coherent strategy around it. Once we had something on paper that managers could talk to, that people could relate to and get excited about, then we could really start leading the change towards a culture of commitment, continuous improvement and shared goals and values.

(Barolsky, 1994)

This was not simply a matter of a general statement. Palmer then embarked on a detailed programme of change. This was largely on three fronts: systems (especially safety and HR systems), capability and team leadership and membership. He and his team outlined key strategies:

• developing a ‘customer-focused’ culture;

• securing the company’s resource base;

• restructuring the product mix;

• consolidating market leadership;

• improving the company’s cost position;

• reorienting external affairs (Barolsky, 1994).

Joe Grimmond, who was at the time Hamersley’s chief employee relations’ consultant, explained that:

We recognised that many of these systems had been around for decades and were very much part of the Hamersley way of doing things. While we realised it would be difficult to fight against this momentum of the past, the senior management team had a strong resolve to succeed. This success wouldn’t be measured by actual modifications to the systems themselves but rather by what behavioural change resulted from the changes to these systems.

The team identified several key systems that were in box B (authorised but counter-productive – see Chapter 10):

• seniority system of promotion;

• command and control task assignment;

• overtime system used as reward consequently encouraging inefficiency;

• pre-agreed leisure days off and personal days off, sick leave and stop work meetings;

• demarcation between unions and staff, for example, supervisors could not help in hands-on work;

• award pay increases on the basis of qualification not use of skill;

• active encouragement of new employees to join the union.

Palmer studied and learnt from the Comalco work, especially in New Zealand, and sent employees to the NZAS site. He started with key work around safety to build trust and implemented a new safety system. This initiative was led by managers in Level III roles and the general managers.

He then initiated the Working Together programme and, with Macdonald, co-ran courses for his team (roles at Level IV) and all people in Level III roles – thirteen courses in all. He used these to explain what he wanted to achieve and how he intended to achieve it. These courses (as mentioned in Chapter 18) covered all the topics of values, culture and mythologies; work complexity and capability; and the steps and traps of team leadership and membership. He and his team then reviewed the leadership roles and who was suitable.

Then the GMs in Level IV roles presented the plan of work strategy in person to all employees. What was specifically emphasised was the need to be world competitive and 100% reliable in supply, a target some thought was impossible. The use of the systems leadership theory in detail was complemented with business improvement projects including quality initiatives.

In June 1992 there was a major strike over refusal of an employee to join the union, which the company was no longer making compulsory. Despite the fact that enforced closed shop was illegal, the mythologies of the union leadership predicted that Palmer and the leadership at Hamersley Iron would give in. There was huge dissonance created when Palmer backed the individual’s rights.

All the details of this strike are not covered here. However, the highly significant and symbolic battle to protect the right of people to work and to prevent harassment created many new mythologies – not least that the ‘management’ was prepared to be courageous and respectful of the law. The Australian Industrial Relations Commission ordered a return to work on 19 June backed by the prime minister of Australia and the federal minister of industrial relations. The strike continued. On 29 June, workers voted to return to work.

In early 1993, the company was restructured. The workforce reduction of almost 20% was unusual in that proportionally as many ‘staff’ roles went as roles covered by the ‘award’. Voluntary separations were accepted by nearly all to whom they were offered. In fact a greater number left than was intended through the voluntary scheme.

This led to an opportunity to improve many systems, including a new recruitment system using input from shop floor team members. A fair treatment procedure was introduced and the Working Together course rolled out to all employees. Paul Piercy, a GM, commented:

Using these courses to introduce team concepts also provided us a chance to emphasise to supervisors the importance of their role in the new Hamersley. It was also a chance to start engendering a management style that was more participative and attuned to the needs of team members. For the shop floor employees it was a way for us to communicate Hamersley’s vision and strategies and to start building some trust and commitment to them. Most importantly, the courses were the beginning of creating more effective teams on the shopfloor.

(Barolsky, 1994)

Piercy and all the GM operations co-ran these courses as did leaders in Level III roles alongside Macdonald Associates’ co-presenters.

Smaller symbolic changes were made, including no preferential parking for staff, and supervisors eating with their crews.

Eventually staff offers of employment were made at the end of 1993. By 1 January 1994, 89% had accepted. The results were similar to those at Comalco – production increased and costs fell (Figure 20.9).