CHAPTER 1

Reformation, Transformation, and Creation: Defining Autonomous Transformation

- au·ton·o·mous ȯ‐ˈtä‐n·mous adjective

- 1: having the right or power of self‐government

- 2: existing or capable of existing independently1

- trans·for·ma·tion ˌtran(t)s‐fər‐ˈmā‐shən noun

- 1: an act, process, or instance of transforming or being transformed (verb): to change in composition or structure2

Autonomous Transformation, on the surface, could sound to many like the final process by which all work will be automated.

Although it does involve systems that can operate autonomously, which for many invokes concern about the elimination of jobs, Autonomous Transformation is instead the transformation of jobs across all verticals and levels, increasing the autonomy of human workers—that is to say, the right or power of self‐government, existing or capable of existing independently.

Human autonomy and machine autonomy are two halves of the same coin, incapable of existing without one another in the context of the twenty‐first century. The process of breaking tasks down into individual work elements that can be either automated or assigned to humans was, conceivably, the only path to meeting the demand for production placed on systems and organizations in the late nineteenth century and throughout the twentieth century. And as long as there are repetitive tasks that cannot be learned by or taught to machines, humans will need to operate those tasks.

With autonomous technologies, this is no longer the case. Networks of repetitive tasks previously too complex to be automated can now be learned by and taught to machines. This has the potential to transform the labor market and can be imagined as a new entrant to the pyramidal hierarchy of work, pushing humans upward from repetitive toward creative work—from operations toward stewardship.

This is a timely opportunity in the current macroeconomic climate because as organizations face recession, the desire to consider reshoring operations to harden supply chains against the risk of geopolitical and/or logistical challenges, and the loss of expertise as experts quit or retire, organizations need to do more with less, and Autonomous Transformation presents a time‐sensitive opportunity to capture and extend human expertise to empower organizations to create more value with the same number of resources, ensuring business continuity and job stability.

Autonomous Transformation is the process of transforming an organization's products, services, processes, and structures through the reimagining and converting of analog and digital processes and assets to autonomous processes and assets.

A human‐centered Autonomous Transformation carries the thread of the human experience of working within the organization together with the impact to the communities served by the organization through the process of transformation as a means of achieving Profitable Good as well as increasing the likelihood of successfully achieving and sustaining value creation through Autonomous Transformation.

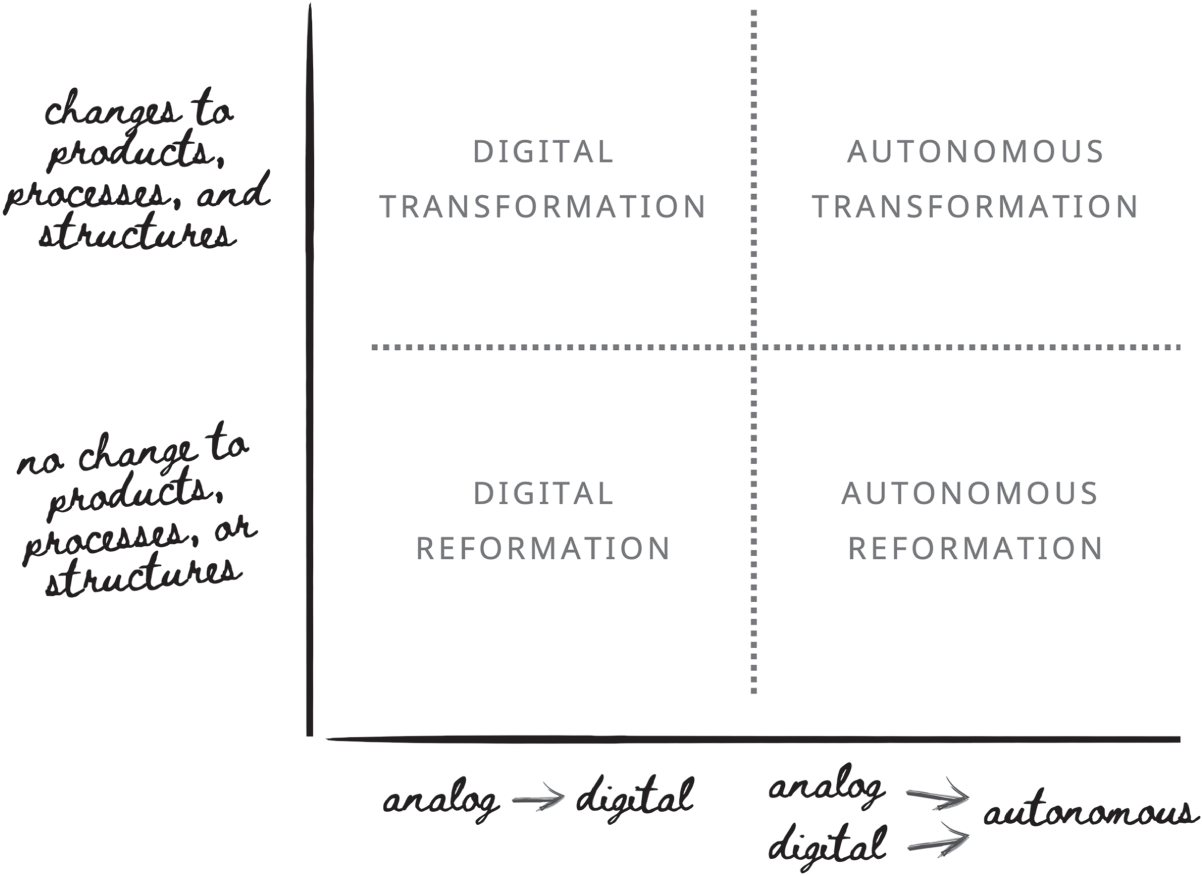

As depicted in Figure 1.1, Digital Transformation is the process of transforming an organization's products, services, processes, and structures through the reimagining and converting of analog processes and assets to digital processes and assets.

This is not to be confused with Digital Reformation, which has been a prevalent market force under the guise of Digital Transformation since the coining of the term Digital Transformation in 2011.

- ref·or·ma·tion re‐fər‐ˈmā‐shən noun

- 1: a: to put or change into an improved form or condition

- b: to amend or improve by change of form or removal of faults or abuses3

Digital Reformation is the process of reforming, or improving the performance of, an organization's products, services, processes, or structures through the conversion of analog processes and assets to digital processes and assets without changing the nature of those products, services, processes, or structures.

Figure 1.1 Transformation and Reformation Matrix

Likewise, Autonomous Reformation is the process of reforming, or improving the performance of, an organization's products, services, processes, or structures through the converting of analog and digital processes and assets to autonomous processes and assets without changing the nature of those products, services, processes, or structures.

An example of Digital Transformation is Netflix's transition from solely sending DVDs in the mail to the invention of streaming. The core product and the processes and structures by which they delivered value to their customer base were reimagined and transformed within the digital paradigm, resulting in a ripple effect that is continuing to shape the trajectory of entertainment.

There are more examples of Digital Reformation than of Digital Transformation, such as within the airline industry. Booking with a travel agent has been largely replaced by booking with airlines or travel websites directly, which has significantly improved the customer experience, but the product, the process by which tickets are booked, and the structure of the airline are fundamentally the same. Checking into a flight has been significantly improved, or reformed, through the ability to check in online, but although the process of checking in has been improved through the converting of analog to digital, it has not been reimagined. Inside the airplane, paying with a credit card to make a phone call from one's seat has been reformed to paying with a credit card for Internet on one's device; the function and structure are the same, but the customer experience has been significantly improved.

An example of Autonomous Reformation is taking place at Bell Flight, where engineers have trained autonomous artificial intelligence agents to land drones based on a curriculum defined by pilots. In order to learn how to land autonomously, the artificial intelligence agent practiced landing in thousands of simulated scenarios every few minutes, thereby learning through experience plus expertise the same way a person learns. This is an important breakthrough, as drones with this capability can land without GPS or any type of radio or Internet signal, which means they can deliver vital medicine and other goods to communities in disaster scenarios, even if towers, roads, and pharmacies have been destroyed. This example is reformational and not transformational because the structure and process of the system itself have not been changed—they have been improved. This example does take a step in the direction of Autonomous Transformation, however, as drones that can land autonomously, together with the ability to take off, fly, recharge, change course, and so on could be leveraged to create transformational new products and services.4

There is not yet an example of a market‐altering Autonomous Transformation, but there are several ventures in the direction of Autonomous Transformation, such as Amazon Go, a retail store without a checkout process because it recognizes its shoppers, personalizes their experiences, and uses their saved payment methods when they walk out of the store.

One could imagine this paradigm being applied to the airline industry, and the ability to walk in and set luggage directly onto a conveyor belt without needing to show identification or wait in line.

Another example in the direction of Autonomous Transformation is in the idea of the Internet of Things sensing when a consumer is low on a given product and making a purchase based on price‐to‐value and logistics. This has the capability to alter the advertising business, as machines are neither designed, nor have the capacity, to emotionally connect with advertisements, and would instead prioritize the best value in the required timing.

The example of Amazon Go illustrates autonomous technologies being leveraged to replace a current job category, whereas the example of the Internet of Things demonstrates the use of autonomous technologies to perform a new function that reduces the overall load on a human (in this case, the resident of the home). The third application of autonomous technologies is extending human capabilities, which can be described in the context of health care.

Health care is one of the most manual industries. Oversimplified, the process is to go speak with and show your symptoms to another person, who then performs a procedure, schedules tests, schedules procedures, prescribes treatment, and/or schedules a follow‐up visit. The efficacy of the visit is reliant on the patient's ability to accurately convey their symptoms and family and personal medical history in a short time frame, sometimes as little as a 15‐minute window, after waiting weeks or months. The demand for the human expertise of doctors dramatically outweighs the supply, resulting in disparity of access to health care and negatively impacting the performance of the health care system as a whole.

In the autonomous paradigm, this highly manual equation could be reimagined to extend the ability of medical practitioners to assist more people, with the potential to lower costs and create more access. An example of this would be the development of a digital twin of every patient that could be sharpened over time with every test, diagnosis, health event, procedure, and hospitalization. This would lay the foundation for faster diagnoses and triaging before a patient ever arrived at a hospital or clinic. In a visit, medical professionals could test treatment scenarios against the digital twin of the patient to verify the best treatment path, and augment their expertise by validating their proposed diagnoses and treatment with a system that had been trained with the expertise of hundreds, if not thousands, of medical experts and research papers, to recommend any other possible diagnoses and recommend tests or treatment plans, with analysis of the implications if they were wrong.

A fundamental capability this addresses that is not possible in today's paradigm is the systemic view of a patient, as even the most well‐meaning practitioners often do not have time to stop and consider every test that could be taken or every subfield of medicine that could be examined to get to the root of a patient issue. A capability like this could leverage expertise across disciplines to recommend tests and treatment that could then be validated by a medical professional before being put into practice. This would benefit patients because they could have more frequent and holistic access to medical expertise, and it would benefit medical professionals because they could support more patients with the same or fewer resources, and their visits would be more targeted and informed with patient background and information.

Both reformation and transformation begin with something that exists, which is an inherent limitation when the system needs something that does not exist, such as in the health care example. These instances, which occur more often than is recognized, require acts of creation.

- cre·a·tion krē‐ˈā‐shən noun

- 1: the act of creating

- especially : the act of bringing the world into ordered existence

- 2: the act of making, inventing, or producing

- 3: something that is created5

Since its creation in 1861, the telephone has continuously been reformed and transformed. Multiplexing, which allowed several calls through the same telephone wire at the same time, is an example of reformation, and it introduced many times the efficiency. The touch‐tone phone is an example of transformation, the cellular phone another transformation, and the smartphone yet another transformation—and since the invention and release of the smartphone, it has undergone a series of reformations.

But the smartphone would not have been possible if it were not for multiplexing, which laid the groundwork (pun intended) for cellular phones, together with a combination of creations, reformations, and transformations across many industry verticals, such as graphical computing, manufacturing capabilities, and scientific creations in batteries, chips, and scratch‐resistant glass (to name a few), and compressed video and audio file formats.

In other words, a desired future outcome, such as a product release like the iPhone in 2007, is not the outcome of reformation, creation, or transformation taken individually. They are each processes, or means, with which to produce an outcome, and the leaders who harness the full potential of the technological and social systems of the twenty‐first century will weave the three processes together, specific to their organization, market, and regulatory context, to arrive at a future point they have envisioned for their organization and/or for society.

Weaving Our Way to the Moon

The Jacquard loom, patented in 1804 by Jacques Marie Jacquard, was an invention that combined several preexisting inventions into a machine that made it possible for unskilled workers to weave fabrics with complex and detailed patterns in a fraction of the time it took a master weaver and an assistant working manually.

This development had important social and technological impacts. Before this invention, fashionable cloth was only accessible to the wealthiest in society. Now, such cloth adorned with intricate patterns could be mass‐produced.

From a technological standpoint, the Jacquard loom laid the foundation on which computing and computer programming were developed. When Charles Babbage invented the first digital computer, the Analytical Engine, he used Jacquard's punch card concept. The punch card method developed by Jacquard persisted until the mid‐1980s, and was used in the Apollo missions, as well as mainframe machines created by IBM. Ada Lovelace, the first computer programmer, became the world's only expert on the process of sequencing instructions on the punch cards that Babbage's Analytical Engine used, and famously said “The Analytical Engine weaves algebraic patterns, just as the Jacquard loom weaves flowers and leaves.”6

Standing in front of one of the last working Jacquard looms, in the Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, is a powerful experience, and the two‐story machine is a looming physical representation of a creation that transformed a commodities market and, in doing so, laid the foundation for several steps of world‐changing creation, reformation, and transformation.

History is filled with examples of the cycle of creation, reformation, and transformation, and the world needs creators, reformers, and transformers. Creators build new capability, whether it is a scientific breakthrough, a business model, a technology, a method, or a system. When that creation is introduced into the market, without a reformer to iterate on and improve the system, the value of the creation will be short‐lived. Without transformers to reimagine the application of that creation across sectors or in combination with other creations, the creation will never drive systemic or worldwide value and society will not realize the full benefit or potential. Conversely, transformers need a steady supply of creations, stabilized through the process of reformation, as change agents with which to drive organizational and market transformation.

It should be noted that there is not and should be no value judgment inherent in these definitions and examples. For some organizations, reformational programs may be more attractive and a better fit for their risk tolerance or market position than for others. Individuals may find themselves attracted to and specializing in creation, reformation, or transformation, and leading organizations will need each of these functions and leaders who can facilitate and orchestrate the expertise and vision of these functions to achieve cross‐organizational objectives.

Job Protectionism, Job Fatalism, and Job Pragmatism

The story of the Jacquard loom, viewed through the lens of the development of the computer, is innocuous and fascinating. Through the lens of the work landscape at the time, riots broke out in Lyon, France, attempts were made on Jacquard's life, and there were concerted efforts to destroy any Jacquard looms within the city limits.7

This is a historic example of a paradigm that these technologies and the title of this book are likely to first bring to mind, in which machines take over work that currently creates human jobs. Autonomous Transformation can and will be used to replace current human jobs, the same way that whalers lost jobs when oil lamps were invented and horse carriage drivers lost jobs when the automobile was invented, but forward‐thinking leaders within those organizations and industries can plan ahead to ensure that those impacted by those changes are able to transition to other jobs within the organization and maintain steady employment.

In other words, within the amount of time and investment it takes to get a technology or group of technologies developed and integrated to the degree that they could reasonably handle all of the tasks currently handled by a human, there is ample time for the humans occupying those jobs to be informed of the coming changes, offered opportunities to train for other positions, and plan for a smooth transition to the next position within the organization.

This means that a sudden reduction of jobs due to automation or machine autonomy is the result of either a failure to plan, a failure to communicate, or an intentional choice to withhold information regarding a coming change.

In the wake of the Industrial Revolution, jobs have become equated with people, and it has become a value and symbol of integrity to be a proponent and/or agent of “job protectionism,” or the belief that certain jobs or industries should be shielded from competition or other factors that may threaten their existence, even if this means sacrificing other economic or social goals.

Another philosophical lens through which the technology‐fueled evolution of work and society is examined is “job fatalism,” the belief that there is little or nothing that can be done to protect jobs or industries in the face of economic changes or competition. This view holds that the forces of globalization, technological advancement, or other factors are so powerful that they will inevitably lead to the loss of certain types of jobs or industries, regardless of any efforts to protect them.

Both of these beliefs are short‐sighted and ill‐suited for the era of artificial intelligence.

Job protectionism reduces competitiveness, as shielding jobs or industries from competition protects them in the short run but makes them less competitive in the long run, ultimately resulting in broader‐sweeping job loss and harming economic growth.

Job fatalism can lead to a sense of resignation or hopelessness among leaders, workers, or policymakers, who may feel that there are no viable solutions to the challenges facing their communities or industries.

An alternative approach, “job pragmatism,” examines the job market together with a belief that emphasizes practicality and effectiveness, rather than a dogmatic adherence to a particular ideology or principle. In the context of the future of the job market, a pragmatic approach would involve balancing the need to support existing jobs with the need to promote innovation, growth, and efficiency in the economy as a whole. This might involve measures such as targeted training and education programs, incentives for businesses to invest in new technologies and processes, and social safety nets to support workers during periods of transition or displacement.

It is the responsibility of organizational leaders to design workforce transformational strategies as an integral part of broader reformational and transformational strategies, and beginning with this consideration yields Profitable Good, preserving organizational legacy knowledge and expertise, engendering loyalty, and contributing to a healthy organizational culture.

Preservation of Human Work for Human Experiences

A world transformed and shaped by autonomy at all costs is a world devoid of basic human experiences that are inextricably tied to the nature of a product or service. Imagine a mall in which the only humans were the shoppers, or restaurants where only the diners were human. It would be dystopian.

Not all manual or transactional work is created equal. We are wired for human connection and although full autonomy could appear profitable in the short term, organizations that explore this will find that the market will rebound quickly in favor of organizations that retain human connection where it matters most. This has been demonstrated rigorously in the field of customer service.

In examining the potential of autonomous applications within an enterprise, organizations need to consider the customer and employee journey and expectations of their brand and their industry, both the minimum expectations to retain customers and employees, as well as opportunities to layer in human experiences to delight customers and increase customer and employee loyalty.

A customer may not leave a brand over having to wait in a virtual queue or not having a localized or personalized experience in the context of a support call, but they may be delighted by being greeted in their native language by a human customer service agent. Although this is not the core value proposition of the organization, the likelihood for consumers to stay or leave based on their emotional connection with a brand, driven by their access to and experiences with the humans who represent that brand, remains a critical input into the decision criteria and approach to autonomy. In the case where human connection is important, autonomous technologies can amplify the abilities of the human workers fulfilling those connection points with customers and employees.

Creating a More Human Future Through Creation, Reformation, and Transformation

If an organization is awarded the distinction of becoming the most digitally transformed organization in the world, but no one is buying their products and they cannot retain talent, Digital Transformation will have been a means to the wrong end.

Digitally transforming is only valuable if it is helping an organization achieve a specific goal it could not have achieved in the analog paradigm. Likewise with Autonomous Transformation and with acts of creation.

There are some organizations that would and will benefit from peeling back efforts to digitally transform where they see that customers preferred the analog experience, especially where it involved human connection. Here we will observe a form of “Analog Transformation.”

If creation, reformation, and transformation are not goals, but processes by which to achieve outcomes, how do we define the right outcomes?

The first step is to determine a future point the organization would like to reach. This could be as simple as an improvement of profitability on a given product (which may only require the process of reformation), or as complex as creating a new market category.

Once the future point has been determined, as demonstrated in Figure 1.2, the organization can determine what would need to be true in order for the organization to reach that future point (more on this in Chapters 6 and 15), then determine which processes will be required to achieve these sets of objectives.

If the future point is determined to be a future in which no workers are harmed on the job in the context of a company that builds skyscrapers, what might have to be true could include analog outcomes, such as education of and adherence to a rigorous set of guidelines and processes by a workforce that involves a high degree of contractors and with varying first languages. Perhaps those educational resources have already been created but are not easy to access, so a digital reformation process is required along with providing tablets at job sites with many languages, with tracking mechanisms to ensure compliance. In parallel, depending on the largest contributors to workplace injuries, a combination of Digital Transformation, Autonomous Transformation, Autonomous Reformation, and creation initiatives could stitch together incremental decreases in workplace risk until the organization is able to reach its ultimate objective.

The steps of this process are represented in Figure 1.2, demonstrating how organizations that pivot from focusing solely on the process of transformation to the outcomes or the future they wish to manifest will significantly increase the likelihood of successful implementations and eliminating pilot purgatory. Furthermore, suborganizations, partnering together to achieve a mutual outcome, may undergo different processes in parallel. One department may undergo a Digital Reformation process to improve the quality of their data while another undergoes Autonomous Reformation to create digital twins of machinery—the two of which in combination create the foundation of a cross‐organizational Autonomous Transformation initiative that represents the final phase of a strategy to reach a desired future state.

Figure 1.2 Reformation, Transformation, and Creation: The Path to the Future

Survivalism and Digital Darwinism

In the 25‐year period from 1997 to 2022, 59% of Fortune 500 companies that were on the list fell off or went defunct. With this degree of sweeping impact on industries, many have, understandably, framed the need for Digital Transformation within the context of organizational existentialism and the need to survive the waves of change impacting the market.

This is absolutely true, but it is both dangerous and ultimately ineffective when it becomes the sole focus of an organization or its leaders.

The survival paradigm invokes fight, flight, or freeze, and can lead to short‐term thinking and rash decisions. At its best, it is a well‐intended means of making the case for change; at its worst, it is a sales tactic.

Regardless of the intention, a focus on survival is inherently self‐interested. Organizations do not exist solely to benefit themselves, and they do not flourish when they are focused inward. Organizations thrive when they focus on creating customer value and treating their employees and customers well. If the leadership of an organization is solely asking the question of how to survive, how to beat the competition, or how to cut costs, it can be easy to lose sight of why the organization got into the business in the first place.

In the face of the era of artificial intelligence, there is an opportunity to pivot from organizational survival to the betterment of the human experience, both internal and external to the organization.

From a systems perspective, the organization is a part of a broader system and has an impact on the human experience. A reexamination of the organization's role within that broader system can illuminate how digital and autonomous capabilities can improve the organization's ability to deliver on its core value proposition to the betterment of society, which will ultimately enable the organization to thrive.

Notes

- 1 “Autonomous,” Merriam‐Webster Dictionary, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/autonomous.

- 2 “Transformed,” Merriam‐Webster Dictionary, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/transformed.

- 3 “Reforming,” Merriam‐Webster Dictionary, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/reforming.

- 4 Bell Textron, “Bell Intelligent Systems: An Innovation Journey with Microsoft Technology,” February 11, 2021, https://news.bellflight.com/en-US/196184-bell-intelligent-systems-an-innovation-journey-with-microsoft-technology.

- 5 “Creation,” Merriam‐Webster Dictionary, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/creation.

- 6 J. Essinger, Jacquard's Web: How a Hand‐Loom Led to the Birth of the Information Age (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2007).

- 7 Dana Mayor, “Joseph Marie Jacquard—Complete Biography, History and Inventions,” History‐Computer, December 15, 2022, https://history-computer.com/joseph-marie-jacquard-complete-biography.