CHAPTER 17

The Reformational Economics of Omission and Commission

For executives who want to maximize their job security in a public or private organization that deprecates mistakes and ignores errors of omission, the best strategy is to do nothing or as little as possible.

—Dr. Russell Ackoff, in Transforming the Systems Movement

Most people are familiar with the fact that Blockbuster passed on opportunities to acquire Netflix in 2000. What most people do not know is that Blockbuster built a streaming service 12 years before Netflix did that never made it to market.

When Ron Norris, a consulting executive whose team had designed, built, and successfully piloted the first streaming service in 1995 on behalf of Blockbuster (called Blockbuster on Demand), received a call from a senior executive with oversight of the program, he expected a congratulations, gratitude, and questions about how quickly he and his team could bring this to market.

Instead, he was directed to cancel the initiative altogether.

The executive informed him that the new offering would eliminate late fees, which accounted for 12% of Blockbuster's revenue and was therefore not a suitable path forward.

When Blockbuster filed for bankruptcy in 2010, this executive may have remembered the conversation he had with Norris and imagined how differently things would have turned out had he not chosen to cancel the initiative, but one thing is certain: that decision, despite disastrous consequences to the organization, had no negative impact, aside from opportunity cost, on the finances or reputation of the executive responsible.

This is because leaders and organizations are measured on their errors of commission, actions they took, but not their errors of omission, actions they did not take.

It is even likely that this executive included a bullet point about protecting 12% of annual revenue in his annual review.

Errors of omission have a higher impact than errors of commission. They are a shadow force with the power to end an organization. As organizational leaders make decisions, they are not aware of what they are not seeing—the risks they are not taking and learning from. Their errors of commission and their successes become a self‐affirming loop until an internal leader disrupts the pattern, or the accumulated errors of omission have grown large enough to pave the path for a new organization to rise and overtake the legacy organization in the market.

I mentioned in Chapter 16 that in the context of Autonomous Transformation, leaders who set a vision for the future of the organization and a strategy to realize that future face the risk that, as their strategy runs its course through the organization's process of translating strategy into action, the current worldview and processes may produce an unrecognizable translation that is not fit for the purpose of creating the leader's desired future.

One of the paradigms that comprises these processes is that accounting systems only record acts of commission.

- What did it cost Blockbuster to acquire Erol's in 1990?

- What did it cost Blockbuster not to move forward with Blockbuster on Demand in 1995?

- What did it cost Blockbuster not to acquire Netflix in 2000?

The first question can be answered in moments with an Internet search. The second and third? They can be modeled in hindsight, but were not accounted for at the time.

In the era of artificial intelligence and the steep rise in complexity across many advanced technologies, accounting only for the risks taken nudges leaders toward maintenance mode. Some leaders ignore this nudge, at great personal risk, because they have a vision they consider to be worth spending their social capital on to step outside of the organization's formal accounting process to bring their vision to fruition.

A social systemic alternative to this approach would be to account for every act of omission alongside every act of commission. As those on either side of the hierarchy of a given decision‐maker present decisions to be made, those decisions, including the other options that were presented, can be recorded.

On a regular cadence, the decision‐maker and team can review the impact of the acts of commission together with the considered impacts of the acts of omission, which can be researched in advance of the meeting. This could create a forum in which the team can discuss and learn, and the decision‐making capabilities of the whole social system can improve.

Imagine if, in considering which leader should be promoted to the executive leadership team, the deciding committee could look to the organization's accounting system for a report on the net impact that leader has had on the organization, not only with the funded initiatives and whether or not they were successful, but with the initiatives that were not funded and the acquisitions or partnerships that did not move forward. This would create a more holistic picture of the individual's ability to discern strategic and tactical investments on behalf of the organization.

From a systemic perspective, this kind of accounting approach would systemically nudge decision‐makers toward organizational reasoning to create, socialize, and document the application of reason in the decision‐making process in order to keep a record of why a decision was made to accompany the record of what decision was made.

Outcome Bias in the Face of Failure

Another organizational dynamic that naturally arises from the emphasis on acts of commission and the disregard of acts of omission is the application of outcome bias when initiatives do not go well.

Outcome bias places less importance on the events preceding outcomes and elevates the importance of the outcome itself when examining a past decision.

This contributes to an organizational culture that unfairly punishes leaders and teams whose initiatives do not go as planned based solely on the outcome, and not on the quality of the plan or on the quality of the execution.

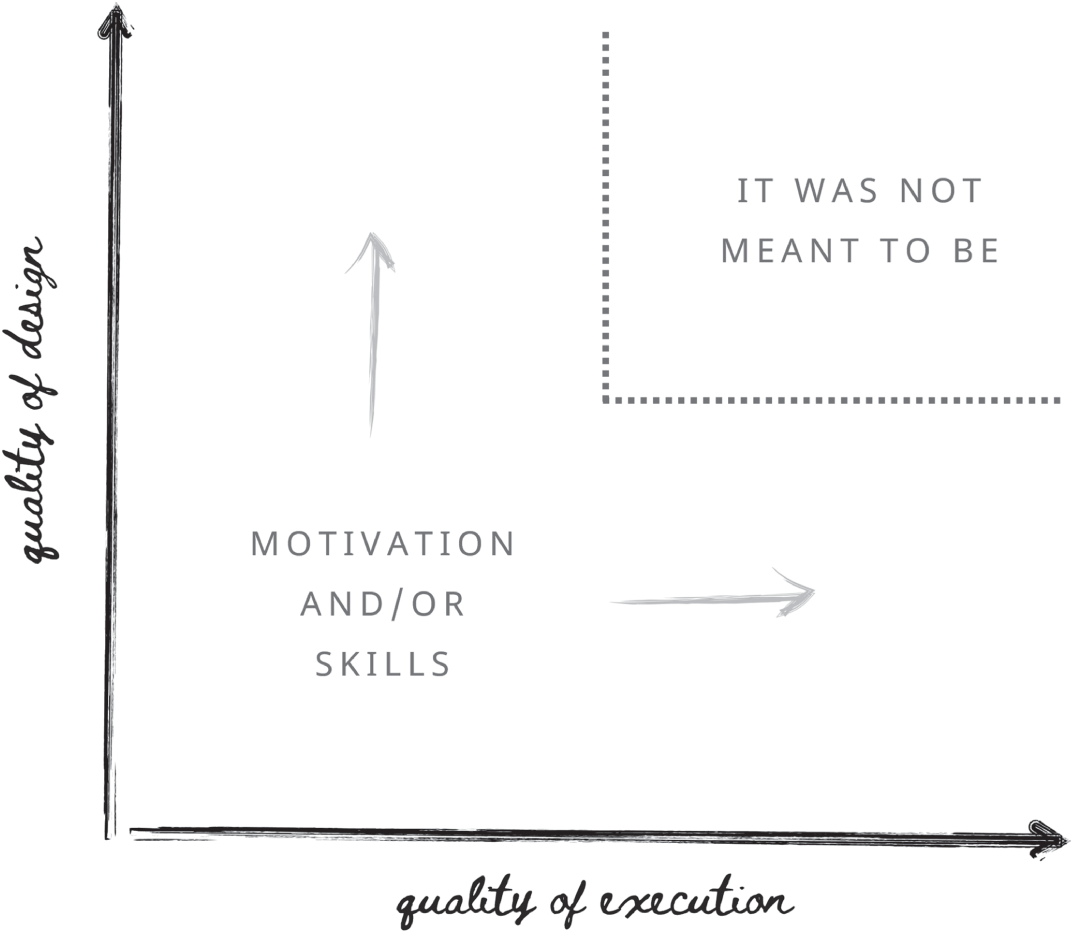

Examining failure through a lens that includes the broader context, such as the quality of design and execution, there are four types of failure:

- Well designed but poorly executed

- Poorly designed but well executed

- Poorly designed and poorly executed

- Well designed and well executed

Leaders and managers who overcome outcome bias and examine the results of a failed initiative through this lens can provide coaching targeted at the preceding events and broader context of the failure to improve the team's ability to design and execute initiatives in the future (see Figure 17.1).

Figure 17.1 An Antidote to Outcome Bias

Conversely, punishing failure for any reason other than what is shown in the bottom‐left quadrant of the figure turns off the innovative part of an organization. If an initiative was well‐designed and well‐executed, but still failed, the reason likely has more to do with the broader systemic context than the team, the understanding of which, through the application of synthesis and analysis together with the team, could yield valuable insights on broader systemic dynamics that need to be reformed, transformed, or created.