Chapter 15

The Art of the Possible

By now, you should have a clear idea of the important business model attributes that collectively characterize the finest companies.

At the top of the list is an ability to produce high equity returns. Companies capable of producing the highest returns on equity with the lowest use of OPM tend to be some of the finest vehicles for wealth creation.

If your business is highly scalable and has the potential to harness operating leverage, so much the better.

Finally, if your business has the potential to assume a leadership position within a large global marketplace, then it has the potential to be a veritable unicorn. And, if you are fortunate to be a founder or leader of such a business and have the ability to retain a large ownership stake, then you have the chance to become an individual unicorn.

The vast majority of successful companies do not come close to the business model ideals that might gain you a unicorn ticket to the Forbes 400. For one, most companies do not service the needs of large global markets, instead focusing on narrower constituencies. Unless your business model is centered on technology or an “asset light” operational approach, you will likely benefit little from operating leverage. In other words, your business model will require business investment growth on a pace closer to your revenue growth if you want to expand. Many companies simply have difficulty scaling to a larger size. Most companies require generous amounts of OPM and OPM equity to realize appealing equity returns. The need for OPM equity can also make it rare for company founders to create big businesses in which they can retain large amounts of personal ownership.

Over 40 years of providing capital to thousands of businesses has given me some perspective on defining wins in business. People make business wins happen, which means that winning in business starts with personal goals and aspirations. In an email blog that I received from Scott Galloway, an entrepreneur, author, and professor of marketing at New York University's Stern School of Business, he made a keen observation:

“People often come to NYU and say, ‘Follow your passion' – which is total bulls – especially because the individual telling you to follow your passion usually became magnificently wealthy selling software as a service for the scheduling of health care maintenance workers. And I refuse to believe that that was his or her passion.”

Instead, Scott borrows advice from fellow author Malcolm Gladwell, which is to invest 10,000 hours of time to become great what you are good at. Finding out what you are good at can take time, and even benefit from some luck. But I have generally found that people who end up being great at what they do, tend to love what they do and who they eventually become.

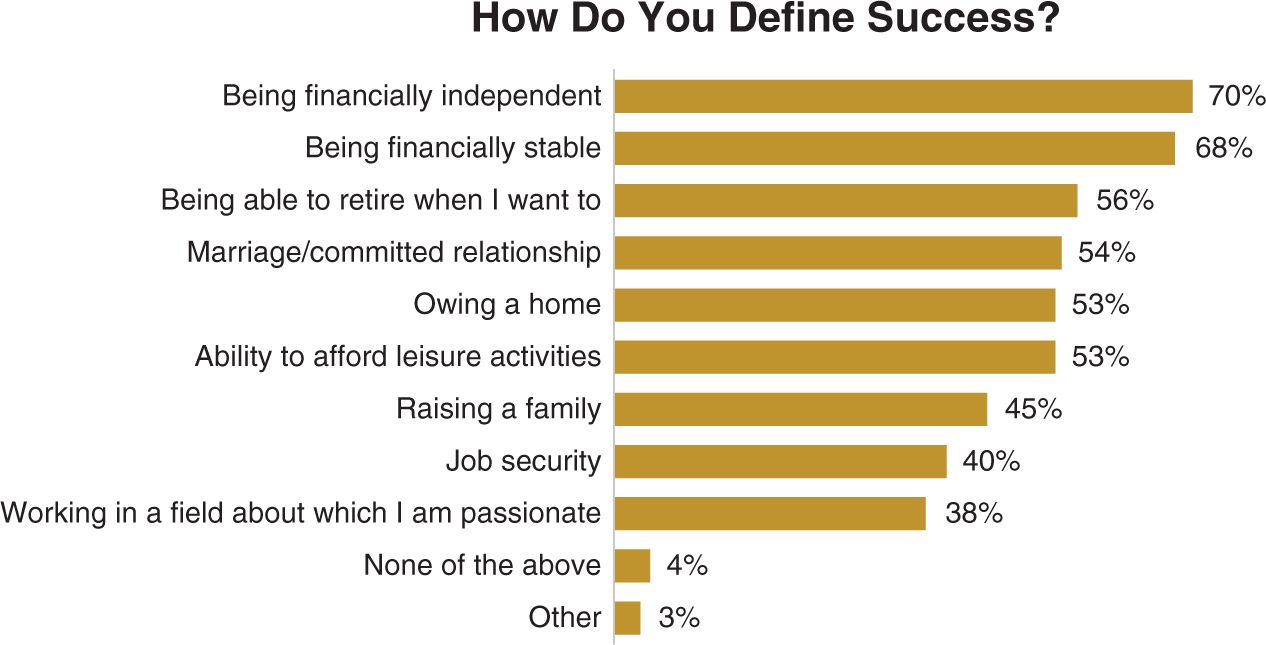

In their 2020 survey of high-income millennials, Spectrem Group, a consulting firm that provides counsel to investment advisors, supported Scott Galloway's observation. Most of the top measures of life success listed by the respondents pertained to financial success. Being passionate about the work that gets them there was way down the list.

SOURCE: Data from Spectrem Group

The companies I have worked for have helped scores of businesses create value for their equity investors and opportunities for their employees and the communities they serve. We have contributed to many financial success stories. We have helped create financial wins. Yet there has not been a single billionaire created. In fact, we declined the one shot we ever had at providing capital to a company whose founder was to eventually be included in the Forbes 400. Our customers, just like the companies I have helped lead, have had business models that imposed limitations on their personal wealth creation potential. It did not matter. Our businesses and those of most of our customers have created impressive amounts of wealth in the course of doing what we have individually and collectively been good at.

There is not only one winning business model for each of us. We have the potential to take what we are good at and apply this ability to create different and formidable business models.

Just understanding this can improve your personal career options. Companies having strong business models tend to have more highly paid employees, together with better career path options and personal growth prospects. Working for companies having solid business models can also provide a resume boost. Given your personal skills and a choice of places to apply them, why not apply them to a company having a superior business model that can use what you're good at?

The Circles of Business Life

Business models are not static; they change over time. In 1901, Andrew Carnegie sold his steel company for more than $300 million, surpassing John D. Rockefeller for a time to become the richest American. In 2021, there were just 15 members of the Forbes 400 whose business interests were centered in manufacturing, with none of them having interests in steel production.

For his part, John D. Rockefeller, who made his personal fortune in the oil industry, is generally singled out as the richest American in history. Yet just 14 of the 2021 Forbes 400 had net worths centered in oil and gas production and delivery, with all but three ranked over 150 and the richest ranked at number 63.

Financier J.P. Morgan was a dominant force during the Gilded Age, ushering in a wave of corporate consolidations, including the acquisition of Carnegie Steel, which became the foundation for the United States Steel Corporation. By the time he died in 1913, J.P. Morgan was also among the richest Americans, with an estimated net worth approaching $120 million. In an era of rapid economic expansion associated with the second industrial revolution, Morgan was in the company of numerous well-known and wealthy financiers, including Andrew and Richard Mellon, Moses Taylor, James Stillman, George Baker, and more.

You know where this is going: By 2021, the Forbes 400 list of richest Americans included but a single name whose net worth stemmed from banking investments.

While traditional banking has fallen from favor as a source of wealth for the richest among us, nearly a quarter of the 2021 Forbes 400 was otherwise engaged in investments and money management. High-tech entrepreneurs may stand out at the top of the Forbes 400 listing, but, numerically, investment management enterprises dominate.

It's not that industries like steel, oil, and banking went away. It's that these industries matured. Over generations, growth in these sectors simply slowed and the equity in the associated great companies long ago created by some of our nation's leading business titans became widely held.

Given all the attention drawn to business unicorns associated with new and disruptive technologies, you might be surprised to know that it is commonplace to see highly successful established businesses that would not be built from scratch today. One of the real estate investment metrics STORE Capital regularly examines and discloses is the amount the company pays for real estate investments relative to what they would cost to replace if built today. Quite often, STORE purchases assets for values below their effective replacement costs.

The reasons for this are generally two-fold.

First, the operating profitability of the company using the real estate is simply insufficient to justify the business investment of building such an asset from scratch. Such events can happen for many reasons. The rising cost to construct a new building can outpace the operating cash flow thrown off by the business model. Or the business model may have simply become less potent over time as the company and sector matured.

The second reason is indirectly related to the first: The market rents for similar properties are too low to warrant their construction today.

None of this is a limitation to EMVA creation, though it can impose limits on corporate growth. If you cannot afford to make new business investments at cost, then expansion is most likely to be derived from the acquisition of other, similar existing businesses. Such growth strategies are commonplace within mature industries.

I have always thought of STORE Capital and its predecessor companies as non-bank financial services providers. At the end of 2020, were you to look at the left (asset) side of STORE's balance sheet, you would have seen approximately $10 billion in real estate assets. That might have led you to believe STORE to be a real estate investment company. But the reason STORE owned this real estate is more defining. We formed the company to provide lease capital to middle market and larger companies across America for their profit center real estate locations. STORE is an important piece of the OPM capital stack puzzle that its customers assemble as they capitalize their companies. Basically, STORE's customers choose them over banking and other options to finance their real estate.

As an effective finance company, STORE's business model must be sufficiently robust to occasionally absorb losses from tenants suffering business model reverses. All OPM providers strive to have business models having margins of error that enable them to absorb occasional losses and still create meaningful EMVA. During my tenure at STORE, the average recovery we realized on non-performing investments approximated 70%. Losses to us, while unfortunate, generally allowed another business to occupy the real estate at a lower cost. For them, the benefits of a reduced business investment contributed to their own elevated EMVA creation possibilities.

Business models change, new business sectors emerge, and established business sectors commonly see their ownership dispersed over time.

There is also a circle of business life.

In 1893, watch retailer Sears, Roebuck and Co. was an early market disruptor that began selling their products through mail-order catalogues. One year later, the catalogue was more than 300 pages, selling everything from watches to sewing machines, toys, automobiles, and even prefabricated houses, all delivered by rail.1 In 1906, Sears became a publicly traded company, marking the first initial public offering for a major retail store chain. The company traded under the ticker symbol “S” and was a component of the Dow Jones Industrial Average from 1924 until 1999. When I was growing up, Sears was the country's largest retailer and my parents regularly ordered from their catalogue, which was far bigger than most large urban area phonebooks.

But then came discounters like Walmart and “category killers” like Home Depot and Best Buy, which eroded Sears's competitive edge and permanently wounded its once dominant business model. In 1993, the company discontinued the iconic catalogue that had initially vaulted Sears into prominence a hundred years prior. Ironically, a year later, Jeff Bezos would start Amazon, taking a page from Sears's disruptive pioneering innovation. The company began by offering a catalogue for books, only this time the catalogue was paperless and online. Amazon then followed a strategy that paralleled the successful road map laid out by Richard Sears a century earlier: The company greatly and successfully expanded its retail product offerings, which would prove damaging to the business models of Sears and many other retailers.

After years of declining sales and encroaching competition, Sears filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection on October 15, 2018.

Business models come and go, and the dynamics of their changes are reflected in our overall economic dynamism.

As Benjamin Franklin said, “When you're finished changing, you're finished.”

Oftentimes, companies suffering business model reverses can be revived. Oaktree Capital, a principal founding institutional investor in STORE Capital, got its start as a distressed debt investment management firm. Basically, its initial strategy was to buy in the debt of distressed companies, which was sold to them at discounted prices by their initial lenders. Key to this strategy was a general belief in the business model potential of the companies whose debt Oaktree would own. Should the company reverse its performance slide, then the debt would be repaid, allowing Oaktree to earn interest income and make a profit by realizing the gain between the discounted price it paid for the debt and its face value. On the other hand, should a company eventually be compelled to seek bankruptcy protection, then Oaktree would be able to convert its discounted debt investment into a meaningful equity stake and potentially recast the bankrupt company's capital stack. Given a new lease on life with a capital stack more suited to the capabilities of its business model, the revived business would be able to embark on a new strategy to do what all highly successful businesses do: create EMVA.

Evolving Capital Choices

Bob Halliday, the founding chairman of our first public company, FFCA, made an observation about business that has stuck with me: “There are no new ideas in business; they just end up being repackaged in different ways.” Well, I would like to think we've had a few firsts, but I basically agree with the observation. And I know for sure that ideas that involve adjusting the Six Variables that comprise business models are not patentable. Good ideas in finance end up being adopted and adapted, leaving little in the way of first-mover advantage to trailblazers.

With that said, OPM and OPM/equity sources, which comprise the essential tools for capital formation, do change. The OPM equity we accessed to start our first company was not available to start the second or third. The OPM equity we accessed to start our second public company was not available to start our first. And the OPM equity we accessed to start STORE Capital was unavailable to start either our first or second public companies. To give a nod to Bob Halliday, the actual capital ideas change little. But the source of capital is definitely subject to change.

When it comes to capital formation and capital stack tools, the business world has changed a great deal in my career. The emergence of investment management firms, which includes all manner of private equity investors and asset managers, is at the top of the list. These are precisely the kinds of companies that collectively dominate the business categories held by members of the 2021 Forbes 400 list of wealthiest Americans. Oaktree Capital, STORE's founding institutional shareholder, is one such company, and eventually gave rise to two members of the elite Forbes list. When I began my career in 1980, there were virtually no private capital firms. In the ensuing 40 years, thousands of such companies have emerged, with new entrants being added to the list every year. These firms include a mix of private equity, venture capital, distressed debt, and lending firms, amongst others.

The amount of private company investment capital that exists today adds to the dynamism of our economy and increases the chances for anyone to become engaged in business.

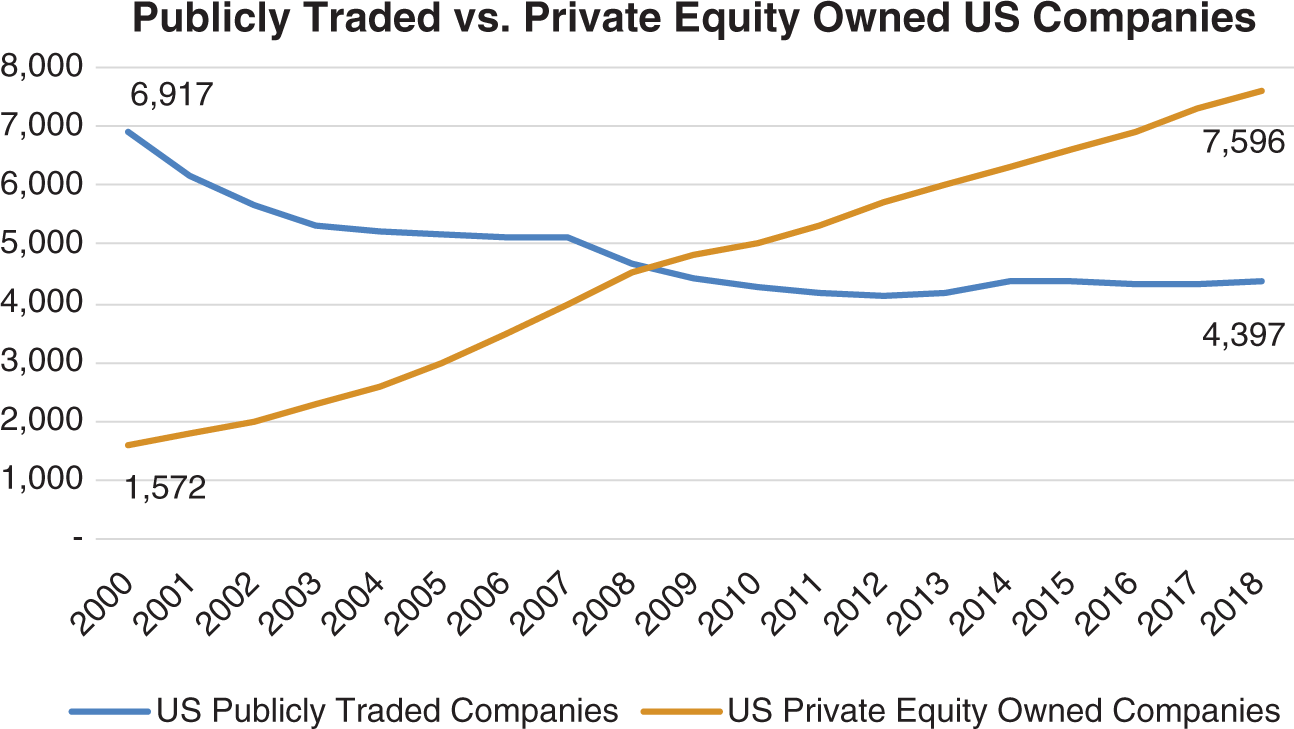

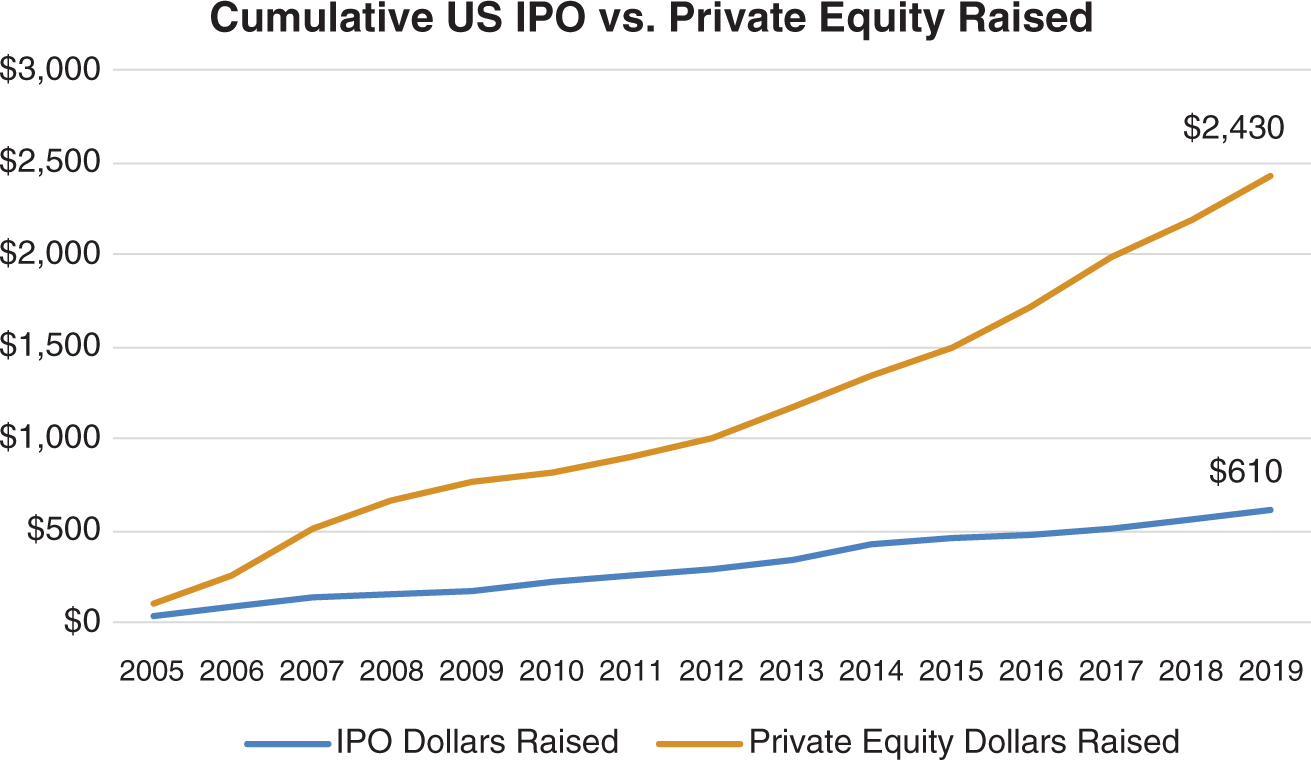

Given the abundance of private capital, corporate capital stacks that involve stock exchange listings have become less desirable over time. Between 2000 and 2019, the number of publicly listed companies declined by more than 38%.2 In 2008, the number of companies held by private equity investors reached parity with the number of publicly listed firms. Ten years later, the number of privately held companies outnumbered publicly listed companies by nearly 75%. But here is a more telling statistic: Between 2005 and 2019, private equity firms outraised public IPOs by roughly 300%. During that same period, IPOs raked in a cumulative total of $610 billion, while share buybacks in the S&P 500 exceeded $7 trillion.3

SOURCE: World Bank, World Federation of Exchanges, PitchBook, Credit Suisse. Data as of December 31, 2017, for listed companies and March 31, 2018, for private equity.

SOURCE: Data from Statistica and Pitchbook

Of course, with OPM and OPM equity subject to change, 2021 would break this trend, delivering a record year for initial public offerings.4 The surge in public company interest was propelled by low interest rates, high levels of investor liquidity and an appetite for emerging technologies having outsized growth potential. Consequentially, many of the newly introduced public companies possessed business models that were not thoroughly proven or defined. Driving more than half this IPO wave was the use of “blank check” companies whose purpose was to ease the simplicity of introducing private companies to the public markets. As a result, the net number of publicly traded companies did something it had not done in decades: increase. Meanwhile, private equity investments did not lose any of their luster, with assets under management and uninvested capital at or near record levels.

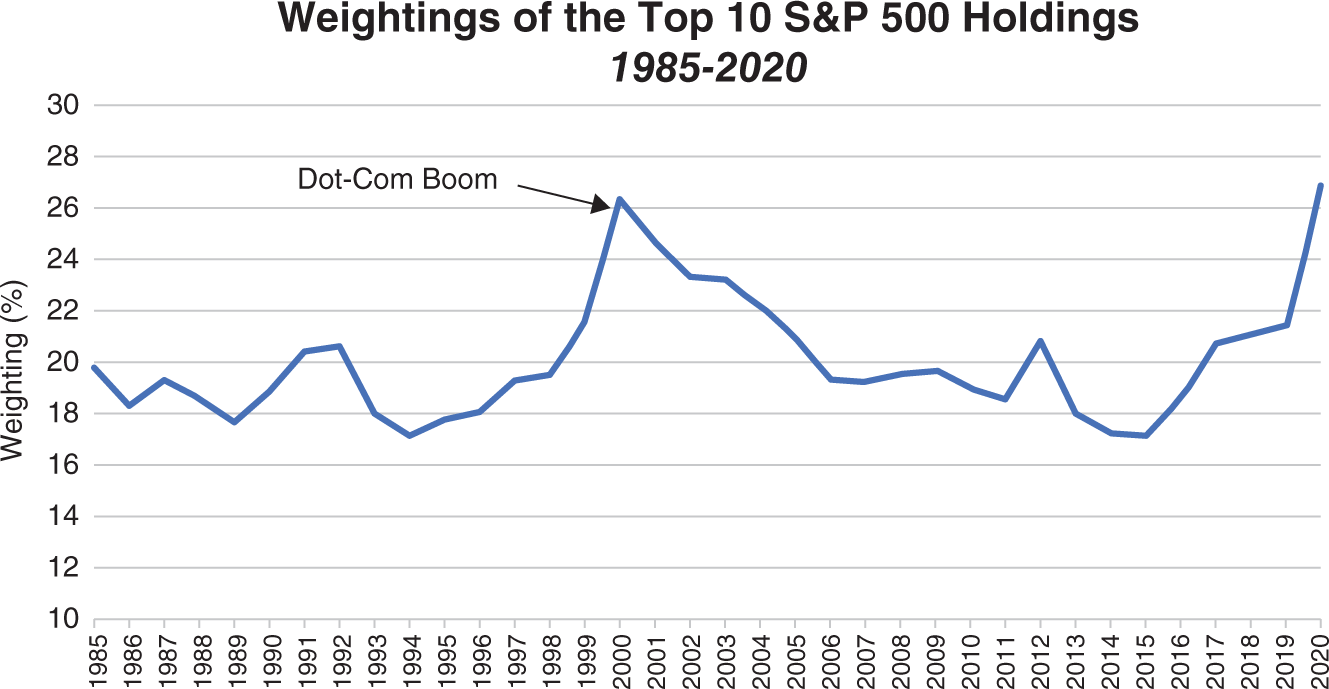

Just as the richest among us make for interesting study into the best business models of the ages, capital market changes deserve our attention because they reflect broader capital formation and capital stack trends that can impact the business community. In the public markets, there has been a distinct trend toward fewer companies, with investor sentiment favoring technology-driven growth companies. Meanwhile, the 10 largest companies by equity market capitalization in 2020 had grown to a high not seen since the dot-com boom, representing approximately 27% of the weighting of the S&P 500.

SOURCE: Data from Morningstar Direct

Value vs. Momentum Investing

Public stock trading patterns have meaningfully changed over my career, with the advent of commission-free trading platforms. Trading commissions used to impose frictional cost that limited trading activity. No longer is that true. During my tenure at STORE, we estimated that fully two thirds of the average daily trading in our shares was done by “day trading” investors who held on to our shares for mere minutes or hours. The growth in trading activity has had an undeniable impact on daily trading volume, which has the near-term potential to alter public company ownership and influence public market valuations.

Discount brokers are incentivized to encourage trading frequency, given that trading order flow comprises an important source of revenues. When opening my personal discount online brokerage account, I was interested to see what tools the various trading platforms offered that would allow me to evaluate my comparative investment performance. I wanted to know how I had done relative to the S&P 500 and other broad benchmarks. None of the online trading platforms I approached offered such performance evaluation tools. Knowing this gave me the sensation of being locked inside a Las Vegas casino having no windows or wall clocks that would allow me to know the time of day or the time spent gambling. The online trading firms did not want to help me understand how well I was doing at investing. “Buy and hold” value investment strategies, when viewed from the vantage point of discount brokerage firms, were less desirable. They simply wanted me to trade more.

In such a heady trading environment, long-term value investment strategies, which depend on fundamental corporate financial analysis and an understanding of equity return components, tend to be less in favor. After all, many of the day trades in STORE shares are placed by investors having little idea of what the company does, instead relying on trading algorithms that capture what they believe to be relevant relative value relationships. In this context, momentum can be important. I am not alone among business leaders in my counterintuitive observation that equity analyst “buy” recommendations tend to become far more frequent the higher the stock price.

With all this said, my observation is that, over the long term, corporate performance fundamentals win out. There is no long-term escape from the Six Variables of equity returns.

Value investing, which relies on an understanding of the Six Variables, may not be the dominant daily trading strategy of public company investors, but it still dominates.

For the millions of private companies and the entrepreneurs that found and lead them or the thousands of asset management firms that invest in them, value investing is generally all that matters.

Business investment components and operating cash flows enable OPM decisions.

The amount of cash flow left after paying for OPM enables YOM and OPM equity decisions.

And the sum of OPM, YOM, and OPM equity defines business valuation.

It's that simple.

Defining a Financial Win

Given the Six Variables underlying wealth creation, together with the fuel provided by compounding, what is a realistic aspirational financial win?

Over an 11-year period in the early part of my career and over 76 episodes, Robin Leach, an English entertainment reporter, had a successful syndicated television show called Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous, where he would highlight the palatial dwellings and extravagant trappings of the well-to-do. Shows like this, together with the annual attention drawn by the Forbes 400 and other media devoted to the flamboyantly wealthy, provide a misleading picture of what it means to be rich. The members of the Forbes 400 are not simply rich. They are extreme outliers beyond rational aspiration.

In 2020, there were estimated to be 927 billionaires in the United States out of a population of approximately 330 million people. Collectively, they controlled an estimated $3.7 trillion in assets, or an amount approximately equal to the annual gross domestic product of Germany, the world's fourth largest economy. Nearly 60% of the members of this group are self-made, and nearly all the fortunes in this group emanate from businesses boasting potent business models that have contributed meaningfully to our collective economic prosperity.

To live in a time where we can bear witness to significant amounts of wealth creation is historically rare and has had a positive impact on the majority of Americans. The revolutionary forces and capital formation that enabled the rise of the recently superrich doubtless helped the careers of many businesspeople. When I started my career in 1980, there were likely fewer than 10 billionaires. Two years later, Forbes produced the first list of wealthiest Americans. The richest person on that list would not have even made their 2020 list. In fact, just one name on the 1982 list remained there through 2020. By 1987, the number of billionaires had risen fourfold to nearly 50, and the growth of the superrich has continued unabated since then.

When it comes to a realistic assessment of what constitutes personal wealth, it helps to take a step back. Just 10.4% of American households in 2019 had a net worth outside of their primary residence of more than $1 million. Realistically speaking, if you could be in this group, that would be a significant win. Just 1.2% of households had a net worth between $5 million and $25 million. And just 196,000 households, or about .2% of the total, had net worths in excess of $25 million. Buried somewhere in that last number are the nation's 927 unicorn billionaires.

Most importantly, and most concerning, roughly 64% of American households had a net worth less than $100,000 outside of their home, with much of that group having no savings. In fact, a survey conducted by GOBankingRates in June 2020 found that 40% of Americans aged 55 to 64 had no savings at all.

| 2019 US Household Wealth Distribution | ||

|---|---|---|

| Wealth Category 1 | (Thousands) Households | % |

| Less Than $100,000 | 78,284 | 63.7% |

| Mass Affluent ($100,000 – $1 Million) | 31,800 | 25.9% |

| Millionaire ($1 Million – $5 Million) | 11,000 | 9.0% |

| Ultra High Net Worth ($5 Million – $25 Million) | 1,520 | 1.2% |

| $25 Million Plus | 196 | 0.2% |

| Total | 122,800 | 100.0% |

1 Wealth excludes primary residence.

SOURCE: Data from Spectrem Group, Market Insights 2020 United States Census Bureau

The median US household income in 2020 amounted to just below $70,000, with a median individual savings below $10,000. Indeed, the majority of Americans have little in the way of savings apart from Social Security and defined benefit pension plans, with the latter increasingly rare in corporate America.

| 2020 US Individual and Household Income Percentiles | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentile | ||||||

| 25.0% | 50.0% | 75.0% | 90.0% | 99.0% | ||

| Individual Income | $23,000 | $43,206 | $75,050 | $125,105 | $361,020 | |

| Household Income | $34,301 | $68,400 | $123,580 | $200,968 | $531,020 | |

| Individual Savings | $0 | $6,450 | $96,000 | $360,000 | $1,770,500 | |

SOURCE: Data from DQYDJ

Between June 2015 and December 2019, the average personal savings rate in the US approximated 7.4%, most of which was skewed toward the wealthiest households. At lower income levels, saving 7.4% of personal income can be difficult, if not impossible. The following table illustrates the lifetime savings that would be accumulated, assuming a 7% monthly savings rate and a 7% annual portfolio return. Given average actual 2020 individual savings at the 99th percentile of nearly $1.8 million and 75th percentile savings of under $100,000, it seems safe to say that computed retirement savings levels in the following table are likely to be more aspirational than real.

| Household Accumulated Savings at 7% of Income | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ($000’s) | Years of Savings | |||||||

| 25 | 30 | 35 | 40 | 45 | ||||

| Household Income | 25th Percentile | $34 | $162 | $244 | $360 | $525 | $759 | |

| 50th Percentile | $68 | $323 | $487 | $719 | $1,047 | $1,513 | ||

| 75th Percentile | $124 | $584 | $879 | $1,298 | $1,892 | $2,734 | ||

| 90th Percentile | $201 | $950 | $1,430 | $2,111 | $3,077 | $4,446 | ||

| 99th Percentile | $531 | $2,509 | $3,779 | $5,579 | $8,131 | $11,748 | ||

SOURCE: Data from DQYDJ

Saving for retirement is hard and requires a dedicated effort. It also takes a great deal of time. After 40 years of monthly savings of 7% of household income at a rate of 7%, those in the 90th percentile would have just over $3 million saved. In the 1990s, financial advisor William Bengen created the 4% rule of retirement withdrawal as a guidepost for safe pre-tax retirement income. That would mean that a retiree having $3 million saved could withdraw $150,000 annually, while a retiree having $500,000 saved could withdraw $25,000. Social Security and other retirement benefits would add to annual pre-tax post retirement earnings potential.

It can be daunting to think of the amount of retirement savings to assemble with a withdrawal limitation of just 4% annually. Yet, by 2021, given low prevailing interest rates and a stock market highly valued in historic terms, certain financial advisors began to openly talk about whether 4% might represent too aggressive an annual withdrawal target.

Given a reading of this book, together with an understanding of what it takes to accumulate $1 million over a lifetime of savings, it should come as no surprise that many of the wealthiest Americans accumulated their wealth a different way. They chose to be business owners and investors. They did not simply invest money that passively went to work for them, but invested in businesses they actively created and owned. Achieving a 7% compound annual portfolio rate of return can indeed make you rich, given a long enough runway and a high enough savings rate. However, owning or being a shareholder in a business capable of creating EMVA is a well-worn path to wealth exemplified by members of the Forbes 400 and widely practiced by entrepreneurs everywhere.

America is broadly in need of elevated financial literacy, which is part of the reason for this book and the STORE University video series that inspired it. At the corporate level, a win is not to harness the latest disruptive technology to create a global enterprise. The initial win is to try to make a decent living. The next level consumed much of this book: Making your company worth more than it cost. EMVA is wealth that is created from thin air, is something only companies can deliver, and is why the world's richest people generally have net worths sourced from personal business investments.

Corporate wealth creation requires a solid business model combined with the miracle of compounding, but the Six Variables of that model need not be perfect. Nor does the company have to address a large marketplace or be highly scalable. Meaningful wealth creation is possible with “old world” companies having numerous business model limitations. As to defining a “meaningful wealth” win, aiming for the 9% of American households having net worths between $1 million and $5 million seems an aspirational goal that is within reach. You are not likely to get on TV, own a jet, or buy a private island, but your economic achievement will have been noteworthy by any measure.

Some Final Thoughts

I personally know of no entrepreneurs who began their journeys with a personal wealth creation target. They simply harnessed what they were good at and applied that skill in the hope it would prove to be of value. In this sense, there exists a loose brother/sisterhood of entrepreneurs. For many of us, the businesses we have created and led enabled us to earn a living and save some money. As to business value creation, some of us failed to create wealth, others were able to create wealth, with a number of us landing a spot in the upper 10% of Americans having net worths greater than $1 million. Many of us have been on multiple entrepreneurial journeys where we have experienced successes and failures. But all of us appreciate what it takes to set up a successful business. The fine lines that separate entrepreneurs often come down to our diverse interests, the markets we work to address, and the problems our businesses are designed to solve.

When I left my first banking job in Atlanta to move to Arizona, I made a choice to devote my career to what I believed I was good at, which was finance. I also had a basic wealth aspiration that I might someday be a millionaire. Ultimately, I and others I work with did far better than we had anticipated. Importantly, our successes allowed us to make a positive difference in the lives of many others. Indeed, our journey is evidence that the art of the possible is always more than we initially believe to be possible.

To come full circle to where I started this book, our study of business within these pages is inextricably tied to the notion of wealth creation. How this all works, from a financial point of view, is not rocket science. My experience has been that good ideas for a business, coupled with business models that hold the promise of EMVA creation and good management teams to execute the plan, are scarcer than the financial capital needed to start them. My experience is that the opportunity to undertake such a business journey is nowhere more possible than right here in America. The dynamism of the American economy is what has enabled a country having just over 4% of the world's population to have approximately 30% of the world's wealth and roughly 16% of global gross domestic product at the end of 2019.5

In my opinion, equity returns lie at the center of the ability of the free enterprise system to outperform every other alternative. They are the prime determinant of OPM, equity OPM, business valuation, and equity market value added. They prompt capital allocation efficiency and direct attention to operating, asset, and capital efficiencies at the hands of business leadership. And the drivers of equity returns can be broken down into six simple, universal business model variables that collectively establish a framework for readily understanding how businesses work and create wealth that ultimately benefits us all.

Notes

- 1. The Sears & Roebuck Catalog, 1893–1993, Curio and Co.

- 2. The World Bank, World Federation of Exchanges Database.

- 3. S&P Global.

- 4. Corrie Driebusch, “IPO's Keep Jumping Higher. How Long Will the Ride Last?” Wall Street Journal, November 18, 2021.

- 5. Juan Carlos, ed., “All the World's Wealth in One Visual,” January 16, 2020, https://howmuch.net/articles/distribution-worlds-wealth-2019; International Monetary Fund; World Bank.