Chapter 2. Understanding Search Intent

“Search intent is of fundamental importance. You just can’t compete in the long term, or even the short term, if you don’t serve intent better than your competitors on the first page of search results. The content on your page and the experience that your website provides must serve what the user is seeking, or someone else will take that ranking position from you.

—Rand Fishkin, in discussion with the authors, August 2019

When someone clicks through to your page from a search result, the thing they came to do is known as their search intent. It’s the task the user is looking to accomplish, the problem they’re trying to solve, or the information they hope to learn when they turn to a search engine. If their experience on your site doesn’t align with those expectations, users will likely return to the search results to find a site that will satisfy their intent.

When you analyze search intent, you not only discover what tasks people are trying to accomplish, but also how they search, what topics they care about, and what language they use to describe things. Understanding search intent is the most critical component of creating a human-centered SEO strategy. It’s what aligns SEO and design in a user-friendly way.

The Benefits of Understanding Search Intent

Both Google and Bing have stated that anyone practicing SEO also needs to understand how to research and design for search intent (http://bkaprt.com/seo38/02-01). Satisfying search intent not only impacts search performance (by improving visibility and conversions, for example), but also enhances a site’s overall user experience. It ensures that you’re answering questions that otherwise would have remained unanswered on your site, and that you’re helping users solve problems.

Studying search intent is probably one of the most underutilized forms of user research. Content writers and UX professionals are at an advantage here, because they’re already pretty ace at trying to understand what users want—and when they satisfy search intent, their content can provide even more value to users.

A better understanding of user needs

Much like interviews or journey mapping, search intent analysis is a form of research you can lean on to better understand user needs. But since this type of research is based on numbers and stats, you’ll gain the formidable power of quantifiable data to back up your decision-making.

Search intent is uncovered by mining deep sets of search data and studying search result pages, a practice we refer to as search intent analysis. This might sound a bit like keyword research, which is typically used to identify the most common or popular terms and phrases searchers are using, with a view toward incorporating them into your content. But it’s not the same thing.

Search intent analysis is a more user-centered way to look at search data. As Dan Shure, SEO consultant at Evolving SEO and host of the podcast Experts on the Wire, says: “Search volume isn’t a number you look at to see how much traffic you can ‘get,’ it’s how many people a month you can help with whatever they are asking” (http://bkaprt.com/seo38/02-02). In other words, how can you design an experience that gives users the information they’re looking for? By prioritizing user needs rather than increased search visibility, your site has the best shot at earning that visibility (and without any extra work on your part).

Understanding search data isn’t just a marketing opportunity. It shows you that real people are behind every single search, trying to find answers to real-life questions. You can help them.

More context for qualitative research

The most common forms of user research—like user interviews—can produce excellent qualitative insights, but they lack quantitative support. Content and UX folks often look for numbers to help validate discovered themes and lend rigor to their qualitative research. That’s where search data comes in.

Estimated search volume—real numbers that represent real people—is crucial to backing up your findings. Search intent research can help identify content opportunities and prioritization, as well as quantify risks—all while being composed of data-driven, fact-based numbers that are indisputable.

Quicker, easier, cheaper research

Many forms of user research require extensive planning, coordination, and budget. Segmenting audiences, scheduling interviews, and hosting journey-mapping sessions are a lot of work. It’s not always easy to incentivize and inspire participation in research studies, much less get budget approved to pay for it. These hurdles stack up fast, often extending timelines or, even worse, blocking research from happening at all.

But search intent analysis doesn’t require the same level of planning, nor is it as costly. Search data is accessible to anyone (limited access is generally free, and deeper access is inexpensive) at any time (you can start your research now, this very minute).

Although the insight you glean from search intent data is always improved by pairing it with user interviews, search intent research is worthwhile even on its own. And getting started doesn’t require coordination with users: to access raw search data from everyone in the world, all you need is a login to a keyword tool.

Google’s Broad Categories of Intent

Back in 2002, in an internal document called “A Taxonomy of Web Search,” Andrei Broder, then vice president of research at AltaVista, wrote that search intent can be categorized into three different types (http://bkaprt.com/seo38/02-03, PDF):

- Informational. The user wants to learn about a topic. Informational searches might look like:

- “is life insurance tax deductible”

- “how long do running shoes last”

- “income tax brackets”

- “fender jaguar vs jazzmaster”

- Transactional. The user wants to take action—to make a purchase, say, or download a product manual. Transactional search intent is not always tied to buying something. Transactional searches might look like:

- “life insurance quotes”

- “fugazi in on the kill taker on vinyl”

- “RACI chart template”

- Navigational. With this kind of search, someone wants to go to a specific website or find a specific page (perhaps one they’ve visited before). There’s typically only one destination the searcher is trying to get to. Navigational searches look like:

- “aflac claims”

- “amazon.com”

- “powell books”

- “wikipedia life insurance”

- “healthline keto diet”

Google later adopted and repurposed these classifications as Know, Do, and Website, and added a fourth category, Visit-in-person (http://bkaprt.com/seo38/02-04, PDF):

- Visit-in-person. These searches have local, real-world intent; someone is seeking an in-person experience or a brick-and-mortar interaction. Visit-in-person searches look like this:

- “insurance agent in phoenix”

- “thai restaurants open now”

- “movie times”

- “barber shops”

- “discount tire near me”

One of the ways Google utilizes these four types of intent is in the design of its search engine results pages, or SERPs. The classification of intent determines what SERP features appear in order to provide more relevant results. For example, for queries identified with informational intent, Google may insert a featured snippet or how-to video. If it identifies transactional intent, it may display ranking product pages or product listing ads, or guide users to retailers. When visit-in-person intent is recognized, Google inserts business listings with a map or localizes other results to guide people to nearby resources.

Note that in the real world, while some searches fall into a single classification, many fall into multiple areas of intent. A user searching for “the perfect pour over” could be attempting to learn about the best method for making a pour-over cup of coffee, or they could be thinking about buying a setup that makes a great cup. Google recognizes both possibilities (Fig 2.1): informational intent (as evidenced by the featured snippet and video results), and transactional intent (as seen in the product listing ads). It tries to deliver the right answer as quickly as possible, saving the user from having to conduct multiple follow-up searches.

While these high-level classifications are great for understanding the general form of search intent and what kind of rich results and SERP features you should optimize for, they don’t specifically address what the user’s needs are, or the insights required to make design and content decisions that will allow you to earn visibility. It’s not enough to understand that someone wants to make a transaction; you also have to understand what type of information people need in order to feel comfortable making the transaction in the first place. Uncovering these nuanced search needs equips you with the insights to design experiences that truly satisfy the searcher’s intent, and in turn earn visibility.

Analyzing the SERP

The best way to start researching search intent is by analyzing the SERP for the most popular keywords and phrases around your product, service, or subject matter. The SERP can be made up of many different types of content and data elements, and which elements appear for a given query provide clues as to how Google assesses the user’s search intent.

Take, for example, the SERP for the term “life insurance” (Fig 2.2). SERP features on this page include:

- Ad listings (ignore these)

- Blue links with information on cost and quotes

- A knowledge panel with a basic definition

- A “People also ask” box with information on the different types of life insurance

The elements of the SERP provide clear evidence of search intent around the topic of life insurance. Google calculates that users searching for “life insurance” generally want to learn more about what life insurance is and how it works, to find out what kind of plan is right for them, and to get a feel for how much it’ll cost. Various SERP features are presented to try to satisfy that intent.

To get started, choose a search query that’s relevant to your product or industry, and jot down all of the content ideas, topics, and indicators of intent you can find on the SERP. Be sure to ignore any ads; since someone paid for them to be there, they might not reflect actual search intent. At the end of this process, you’ll have a list of search intent ideas related to your topic, which you can use to assess your current content and generate new content.

Note that many different features may appear on a SERP, though they won’t all appear on every SERP; it depends on which features Google thinks will be most useful for your query. Let’s dig into the SERP features that are most useful for studying search intent:

- Blue links

- “People also ask” boxes

- Local packs

- “People also search for” and “Related searches” boxes

- Knowledge panels

- Predictive search dropdowns

Blue links

Blue links are the basic organic results of your search. Over the years, Google’s SERP has evolved to display all kinds of rich search components, from featured snippets to embedded video—yet the staple of the search results page has always been blue links.

Here’s what you’ll want to look for:

- What sites appear, and what insights do they provide? If you search for “life insurance,” you might see third-party review sites, life insurance providers, and educational content publishers—which means Google thinks users want unbiased reviews to help them find the best life insurance, suggestions for where to shop, and information on how to make smart decisions about their purchase.

- What language is used in each link? Do a quick search for “life insurance” and check out the headlines of each result. You’ll see blue link titles with phrases like “types of policies,” “best life insurance providers,” and “whole life insurance.” The headlines offer another clue about how Google synthesizes the search intent. In this case, we see a combined search intent: transactional intent (terms like “whole life insurance” signal that someone is shopping around for plans) is mixed in with informational intent (indicated by phrases like “policy types” and “best providers”).

- What do the organic site links point to? Sometimes, underneath a site listing, you’ll see several other smaller links below the meta description (Fig 2.3). In that same search for “life insurance,” we see that some listings have organic site links to terms like “Life Insurance Basics” and “Life Insurance Checklist.” These links are Google’s best guess at the next step a user might want to take.

Fig 2.3: The four blue links under the main search listing indicate what Google thinks users will want to do next.

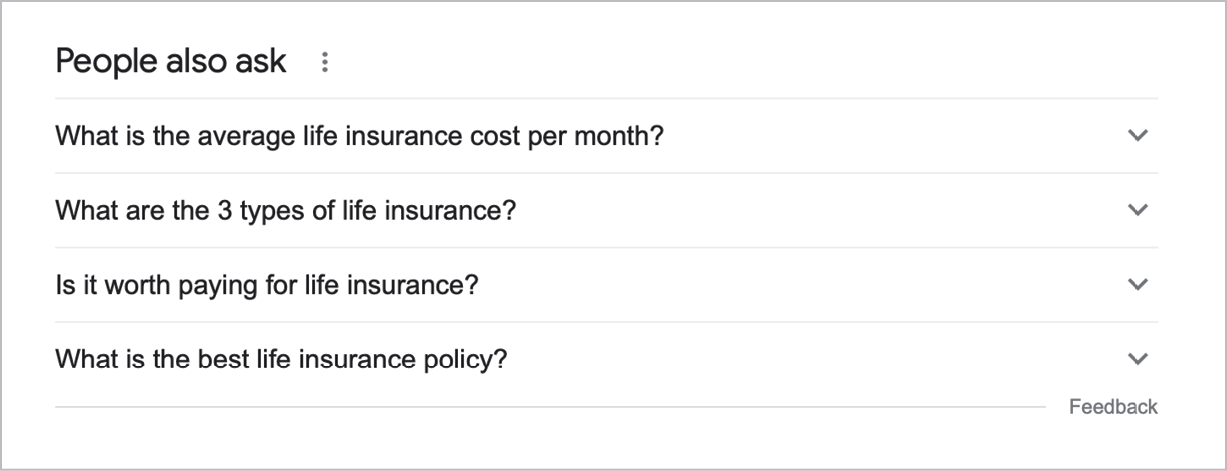

“People also ask” boxes

The “People also ask” box is a SERP element that tries to answer some of the most common questions users have around the search query (Fig 2.4). As you interact with the box, it automatically adds more related questions to the list. To investigate search intent here, interact with each question and see what kind of content is provided in the answers. Take note of any additional questions that populate further.

Local packs

A local pack is a SERP feature that shows local business listings related to your query, usually accompanied by a map (Fig 2.5). When Google inserts a local pack into the search result, you can confidently surmise that there’s some form of visit-in-person intent behind the search. In our life insurance example, we can infer that—along with seeing intent around insurance definitions and product overviews—people might find life insurance daunting to navigate on their own, and would like to reach out to someone locally who can help them make the best purchase decision.

“People also search for” and “Related searches” boxes

If you return to the SERP after visiting a link, you’ll see a new SERP element appear: the handy “People also search for” list. These are additional search queries that are similar to the original, but might differ based on your search history or the initial search listing you clicked on. However, from Google’s perspective, the return visit to the results page means you didn’t find what you were looking for at the visited link, so it will suggest alternate paths to satisfy search intent.

Take note of any new topics addressed in these links: they may help you satisfy more areas of intent (if they apply to you, of course). For example, the linked phrases in the “People also search for” box in our life insurance search suggest a new subcategory that we haven’t seen yet: life insurance for seniors (Fig 2.6). If you were a life insurance company redesigning your site, you might want to create a page dedicated to this topic, or to address questions around life insurance for seniors in your general page content.

Fig 2.6: Google’s “People also search for” box appears when a user returns to the search results after visiting a link.

The “Related searches” box that sits at the very bottom of every search result page attempts to provide the same supplemental information and serves the same purpose in your investigation (Fig 2.7).

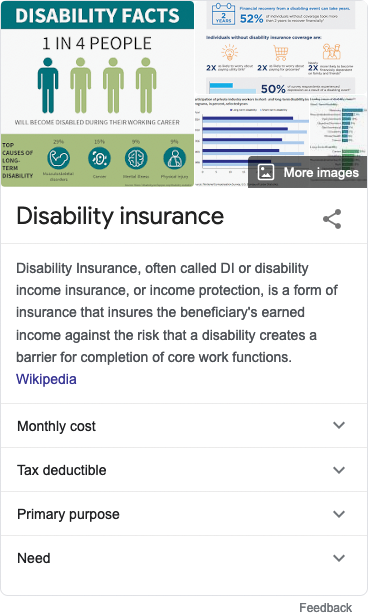

Knowledge panels

Knowledge panels appear in the top portion of some SERPs, and reflect answers supplied by Google’s Knowledge Graph, which can be seen as the output of all the connections Google has made between the data it has found on the web. The panels may contain images, Wikipedia definitions, dates, statistics, cultural notes, or other data Google deems relevant to the search query (Fig 2.8). Knowledge panels are a very telling source of search intent. Google doesn’t insert this feature into all of its results, so when they do, take heed!

Incidentally, there’s nothing you can do to ensure that a particular search query or keyword will get a knowledge panel. Only Google controls when a knowledge panel will appear, and whether an organization, brand, or person has enough authority and relevance to merit one.

Predictive search dropdown

Lastly, scan for ideas in Google autocomplete (Fig 2.9). As you input search terms and phrases that are relevant to your product, service, or subject matter, Google’s predictive dropdown feature can tip you off regarding common queries, local relevance, and trending topics. (Be sure to use your browser’s private browsing mode so your own search history doesn’t impact the search results you see.)

Themes of intent

If you’ve ever conducted user interviews, you know that talking to just a couple of people isn’t quite enough research to uncover overarching themes. Themes only become apparent after looking at your insights in aggregate.

Studying the SERP for search intent works sort of the same way. It’s important to review the entire SERP and all of the features shown for each of your root terms. Yes, it’s natural to see some repetition in SERP elements here—the related searches and search phrases that crop up again and again are themes of intent. Google is showing you the top forms of search intent for your root term. The themes you see most often are typically the most important, and may even correlate to higher search volume.

SERP features vary by query; you won’t see the same features with every search, and while some of the features will show the same intent, others will present new ideas. Scan everything to make sure you don’t miss any important forms of intent.

To continue with our life insurance example, if you framed your themes of intent as potential content topics, your list might look something like this:

- Life insurance basics: definitions, how it works, types of insurance

- How to choose the right plan

- Comparison chart between types

- Validation: reviews, awards, best-of lists

- Life insurance checklist

- Average cost per month

- Average cost by age group

- Life insurance for seniors

- Get a quote online

- Cash value of life insurance plans

- Life insurance calculator (how much coverage do I need)

You can address this search intent in many ways—from improving existing web content and creating new pages to making navigation changes and adding new features and functionality. We’ll talk more about how you can address search intent in Chapter 4. As with all search intent, the organic search visibility wins don’t come from addressing just the biggest themes you see; they come from addressing all of them (as long as they’re appropriate for your organization).

Analyzing the Current Search State

Analyzing the SERP is a research method based on how you’d like to be found in search engines. But you can also learn a lot about search intent by researching how people find your site now, and what they look for once they get there, by looking at the data in Google Search Console and your onsite search.

Google Search Console

The words and phrases people use to find your site now can give you insights into which of your current users’ tasks are most common, which problems they’re looking to solve, which topics are generating traffic (and which ones aren’t), and which pages or page types are driving that traffic.

The only true source of this data is Google Search Console. It’s a free tool that provides insights into organic search performance, as well as information about how Google is indexing your site. One of the tool’s biggest strengths is the depth it provides in keyword-level reporting: it tells you the literal search queries people are using to find your site. While you aren’t able to see which keywords are leading to conversions, the tool does report on which keywords lead to the most impressions, or how many times your site appears in search results for each keyword, as well as the traffic those keywords generate.

Only your organization has access to this data—it’s only accessible to a verified site owner. If you haven’t set up an account for your site or verified the site owner yet, follow the instructions from Google support (http://bkaprt.com/seo38/02-05). Once you’re verified, you can analyze the keyword data by logging into Google Search Console, navigating to the Search results section, and exporting the data as a spreadsheet. For example, in a dataset from the Google Search Console account of a company that provides supplementary insurance, we see queries like “how does short term disability work” and “how much does short term disability pay” (Fig 2.10).

The queries shown in this example (from a product page for short-term disability insurance) indicate a clear theme of intent: how does disability insurance work? In a sense, this theme is about practical details like: How will I get paid? How much can I expect to receive? How long will it take to get my benefits?

In the world of supplementary insurance, transparency and practical information about how various plans work are often avoided because of policy variation and perceived legal constraints. Even if you don’t work in insurance, the pressure to remove web content details that actually benefit users might be familiar to you. But identifying significant search intent around sensitive information in your keyword or onsite search data can help build a compelling case to create more transparency in site content. Giving users the content they truly need to succeed—that’s a major win.

Whatever themes of intent you uncover, analyzing your Google Search Console data can lead to unique insights that your competitors don’t have access to—data that’s unique to your site, especially when it comes to brand-related searches.

Onsite searches

Studying your onsite search logs (in Google Analytics or wherever you store that information) can reveal how people currently search within your website. Some users prefer onsite search functionality to navigate websites, while others only use it as a last resort to find what’s seemingly unfindable. Taking the time to understand what information is most commonly requested or hard to find within your site structure is extremely valuable for spotting unmet themes of intent. A high volume of similar search queries in your onsite search data can indicate either that content isn’t clearly labeled in the navigation or that the website doesn’t address the subject matter at all.

Analyzing Keyword Data

Google collects raw keyword and search volume data from users conducting search queries, which SEO platforms like Ahrefs, Moz, and Semrush then add to their own databases. These platforms offer many tools for finding insights in keyword data.

Before you dive into keyword research, set the scope of your analysis. It’s scalable and can be made to adapt to the complexity of your project. Here are some common dependencies to consider:

- Popularity of the subject matter: The popularity of your research topic is usually directly proportional to the amount of available data and number of relevant keywords. The more popular your subject matter, the more search data you’ll have to sift through and assess.

- Project size: The complexity and scope of your project can drastically change the scale of your keyword research. A full site redesign requiring research on multiple products or services will entail significantly more work than a project focusing on a specific section or page.

- Business value: The significance of the project to your organization can also be a major driver of scope. Research on an organization’s most critical product line, or on a topic that is paramount to the future of the organization’s success, will matter more to the business than research on an average article page. When there’s more at stake, you can expect to spend more time on detailed research.

Assess the context for your project and use it to define the scope and depth of your keyword research.

Select your tool

There are a lot of great keyword tools to choose from. At the time of writing, Semrush, Ahrefs, and Moz are your best options because they offer the deepest set of keyword data and provide a more accurate estimate of search volume using clickstream data (detailed logs of how users navigate websites during a task or session). This data is collected only from users who opt into sharing it with browsers, which then share that data with keyword research tools.

All three tools offer similar pricing, but there are slight differences in their available features and which dataset they use. Tools do evolve, though, so it’s wise to do a little research on your own before making a final decision. Whatever you end up choosing, don’t choose Google’s Keyword Planner for this type of research; because it’s made for paid search, it’s not very transparent.

Generate root terms

To start, you’ll need to formalize your list of root terms, the basic words and phrases most commonly used to describe your products, services, or topics of information. For example, if you’re selling life insurance, some root terms might be “supplementary insurance,” “universal life insurance,” “whole life insurance,” or “life insurance.”

To get a good list of root terms going, jot down the most common terms for your products, services, or topics, as well as any terms you want your site to rank for. Focus on nouns and verbs. If your list feels light, or if you have a product or service that’s less well known or hard to describe, you can look for terms in a few other areas:

- Review any available user research that highlights why people come to your site, what they hope to find, what problem they want to solve, and what words they use to describe your topic.

- Talk to paid-search folks about which keywords convert best for them—those terms are likely to resonate with users.

- Check out chat logs, contact forms, and customer service emails to pick up on what language users choose to describe things.

Make sure you’re exploring as many angles as possible to generate a comprehensive list of terms. Remember, the output of your research will only be as good as your input.

Keep in mind that your final list will likely have dozens of root terms. If your organization has a very extensive line of products or information, like a big-box store or major publisher, your root terms may be in the hundreds—in which case, prioritize your research around key products, services, or topics, and then chip away at them iteratively.

Look to the long tail

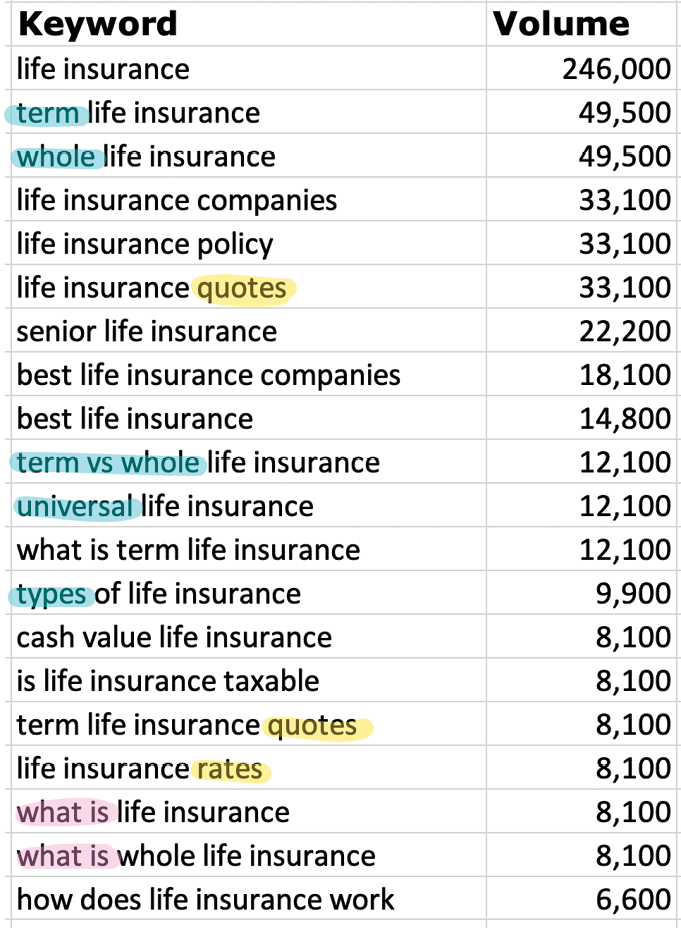

Once you’ve got your list of root terms, enter them into your keyword data tool. The data compiled for each root term shows long-tail keywords—more specific searches tailored precisely to what users are looking for (Fig 2.11).

Although long-tail keywords aren’t as popular or broad as high-level root terms, they make up a substantial percentage of searches around any given topic and reveal the search intent around that topic. (Don’t make the mistake of thinking that long tail means longer keywords! Keywords can be any length; long tail refers to their place in the extremely long tail of a search demand curve.)

For example, if you plug the root term “life insurance” into your keyword tool, you will see long-tail keyword searches like:

- “whole life insurance quotes”

- “what is term life insurance”

- “how much does life insurance cost”

- “types of life insurance”

Every long-tail keyword on the list of results has the root term “life insurance” in it. In order to identify useful themes of search intent, you’ll need to look at the additional words around the root term that make up each long-tail search phrase. For example, nouns like “quotes,” “cost,” and “rates” demonstrate an emerging theme around cost information. Phrases like “definition,” “what is,” and “meaning” show a theme of understanding insurance terminology. And words like “universal,” “whole,” “term,” and “types” show a theme of types of insurance plans (Fig 2.12).

Fig 2.12: We’ve exported the keyword data around the root term “life insurance” into a spreadsheet, along with each keyword’s corresponding monthly search volume. A quick scan reveals several search intent themes: costs and quotes (highlighted in yellow), types of life insurance plans (in blue), and definitional information (in pink).

Fig 2.12: We’ve exported the keyword data around the root term “life insurance” into a spreadsheet, along with each keyword’s corresponding monthly search volume. A quick scan reveals several search intent themes: costs and quotes (highlighted in yellow), types of life insurance plans (in blue), and definitional information (in pink).

Prioritizing Results

Put your exported keyword data into a spreadsheet so you can work with it more easily. It makes sense to pull groups of related root terms out into their own spreadsheet tabs. For example, terms like “life insurance,” “disability insurance,” and “accident insurance” are all types of insurance products, so you could group them in the same tab to quickly spot themes across products.

In each tab, you’ll need several columns, starting with one for the keywords, and another for the corresponding search volume. You’ll also want several other columns for categorizing your keywords thematically, which will help you understand search intent priorities.

Categorizing the keywords

For each keyword, identify and assign a theme in one of the columns. You use data filters to save time in this process. For example, if you use the filtering tool to show only keywords that contain “rates,” you can assign the first entry with the theme of “Costs” and copy it all the way down—instantly categorizing thousands of keywords at once.

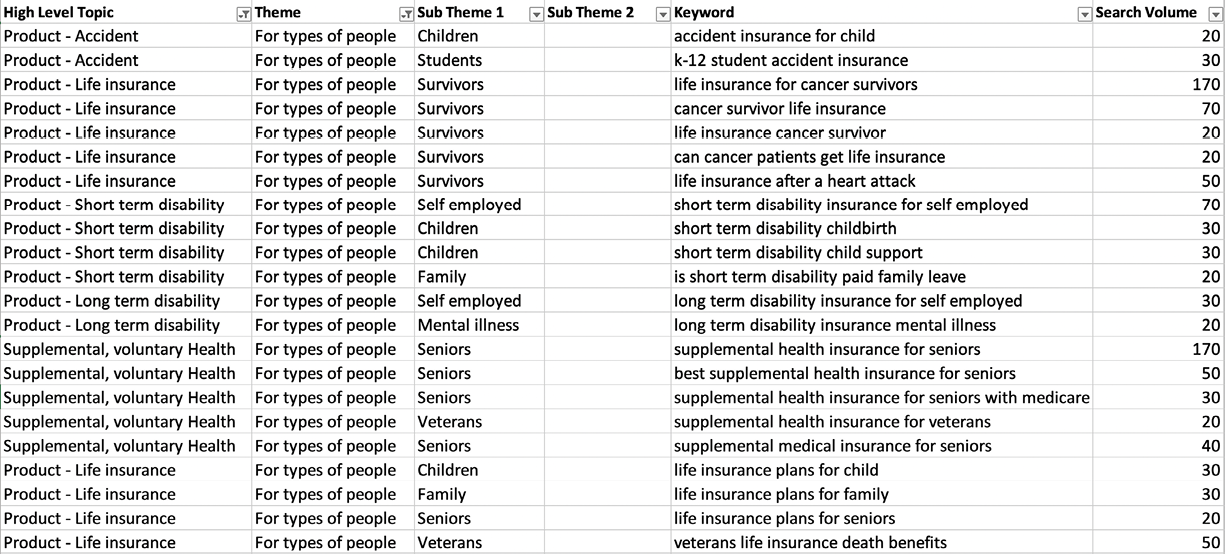

The further you advance through this process, the more theme categories you’ll create. When appropriate, look for opportunities to connect related categories into a larger theme (this is where multiple columns come in handy). For instance, in our life insurance keyword data, you can see search queries for insurance for seniors, children and families, survivors of serious illnesses, veterans, and others (Fig 2.13). By creating a higher-level theme called “For types of people,” you can categorize five or six themes into one. The more specific themes can be included in another column as subthemes, which you can use to segment your data further at the end of the process.

Summarizing the search volume

This is the best part. No, really! You’ve gathered keywords and created a detailed categorization of themes—now you finally get to see which themes of intent are most important to users.

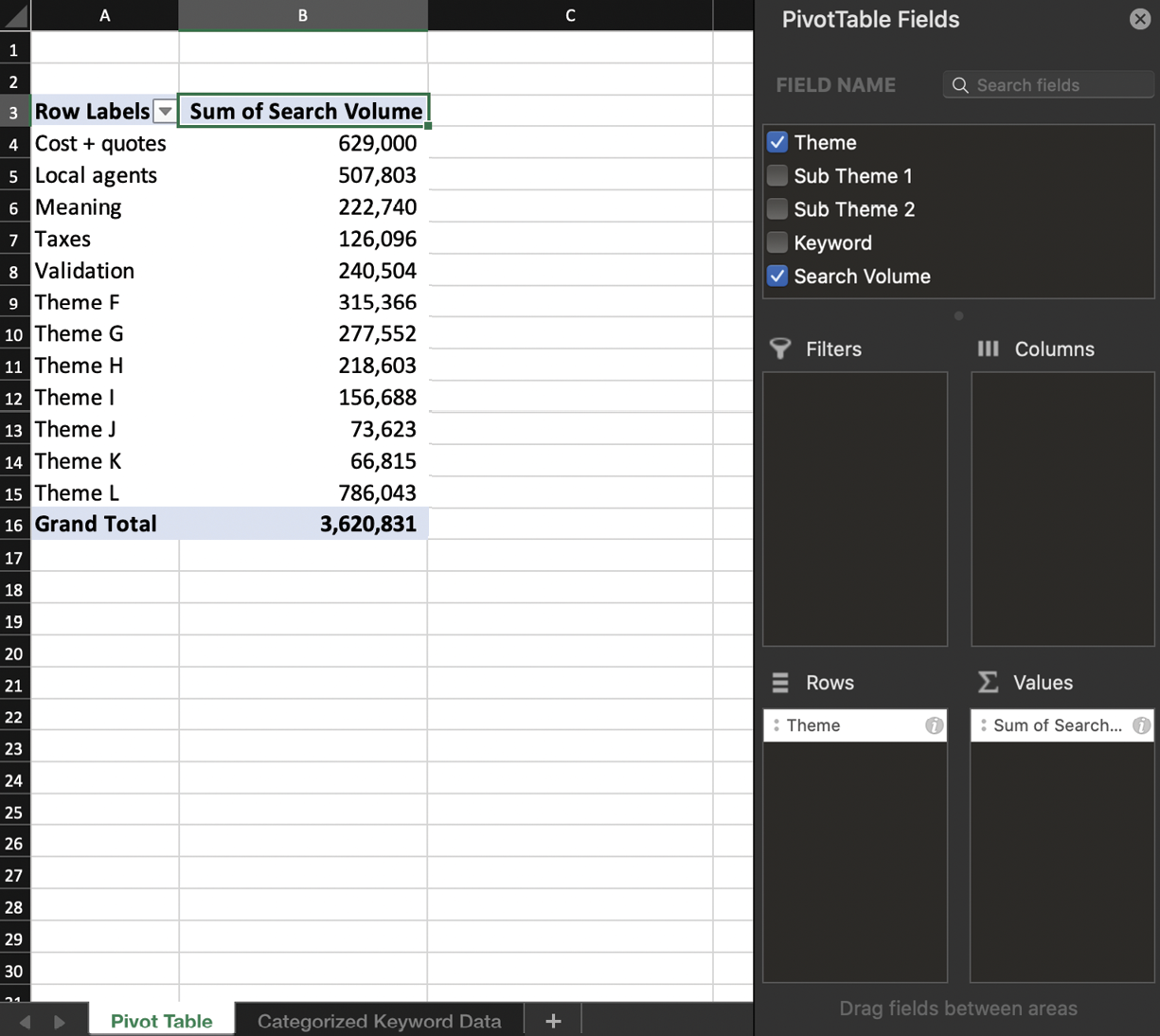

Pivot tables are handy for summing up search volume and breaking it down by theme of intent. In your pivot table settings, choose the themes (or subthemes) you’d like to analyze and display the sum of search volume. Now, instead of confronting an endless list of keywords, or a flood of search volume numbers, you can see how many times real people search for your identified themes in aggregate (Fig 2.14).

You can also use pivot table data to create charts, which can tell a more user-focused and visually captivating story about search volume to internal stakeholders. Pie charts, in particular, humanize the search data. They’re like a magic trick that turns search volume into percentages of people who care about each theme of intent (Fig 2.15).

Sharing search intent research with stakeholders

Now that you know more about what your audience expects from your site, you need folks in your organization to seriously consider addressing that search intent. You want your data to effect real change in your site’s content and design.

Some people will be excited about seizing organic search opportunities, and others might not be. Perhaps they worry that search intent data is really just a way to make them write and design “for robots.” But the way you present your data, and the language you use to talk about search intent, can make a big difference! Here are a few tips:

- Avoid jargon and focus on users. Instead of saying “search volume,” say “the number of people who care about this” or “the number of times people are looking for this information.” Reiterate that you and your colleagues are solving problems for real users, not just for search engines.

- Use pie charts and percentages instead of bar charts and quantities. Pie charts demonstrate how each category of search intent is a piece of the whole—it helps keep the conversation on the larger user experience. Bar charts frame the data differently, emphasizing the popularity of individual categories over the relationship to the overall scope. This can encourage cherry-picking, leading people to fixate on satisfying only the most popular areas while ignoring others that are just as essential to the successful completion of the user journey, despite their lower search volume.

- Present search intent research alongside other user research. Whenever possible, present search volume research along with interviews, user journey maps, or survey results so that stakeholders can get a holistic picture of the user experience and see the search journey as part of the overall customer journey.

When Search Intent Research Isn’t a Good Fit

It’s rare, but not impossible, that you’ll run across a research topic with little or no search data surrounding it. Maybe it’s an ultraspecific niche that’s relatively unknown, or a newly trending topic. Maybe you spot a few people searching around your root phrase, but there isn’t enough long-tail data to reveal any discernable themes of intent. Whatever the case may be, when there’s no search data, there’s no search intent to reveal, and that’s that.

But before throwing in the towel, take more time to explore. It’s extremely rare to find subject matter that no one has searched around. It’s more likely that you haven’t identified the search angle people are really using, or the topic is so new that the data around it isn’t showing up in standard search tools yet.

Check out Google Trends to investigate the popularity of emerging topics. Consult with teammates running paid-search campaigns for your organization. Look to terminology your competitors are using in page titles and headlines on the homepage and key product pages. And don’t forget: talking to real customers is always extremely helpful.

So far, we’ve discussed research for SEO in terms of search intent. But SEO research isn’t limited to search intent analysis, nor is search behavior limited to marketing—it’s intertwined with the user experience. In the next chapter, we’ll explore ways to add a search perspective to the user research you already do.