Chapter 4. SEO in Design and Content

“I think we should stop thinking of it as Search Engine Optimised and more that it is human optimised content. I mean, that’s the whole point of SEO, isn’t it? To get to the human. It seems like a silly distinction to make but I find the way we talk about what we are doing influences how we are doing it.

—Sarah Winters, “Search Engine Optimisation (SEO) and Content” http://bkaprt.com/seo38/04-01)

You never know when a seemingly ordinary project will turn into an opportunity to do truly meaningful work. That’s what happened for us while working on a site redesign for a health insurance provider. The client had embarked on a redesign to reorganize their health plans—along with their site navigation—solely by level of coverage (that is, by bronze, silver, and gold plans, with high, medium, and low deductibles). It was a pretty straightforward approach.

But after we conducted search intent research to understand how people actually look for health insurance information, it became clear that health insurance is about much more than deductibles and copays. Buying health insurance is really buying peace of mind, and peace of mind is personal.

That story was told by search data. When people search for health insurance, they research plans that fit their specific situation or medical needs. Search categories like health insurance for seniors, health insurance for mental and behavioral care, health insurance for pregnancy, and many others began to emerge. In fact, the total search volume from people who wanted to learn more about health insurance for their specific circumstances was just as significant as the number of people searching for costs and quotes.

This data helped guide many of our design decisions—from the navigational structure of the site (where we organized health plans by specific circumstances and types of care shown in the search data) to the core content, features, and functionality of the pages themselves.

Now that you’ve gathered search-specific insights for your project, it’s time to use them to guide the content and design decisions ahead. Beyond using search data to design better experiences, search engine intent must be accounted for at key points in the content and design process for effective SEO:

- user journey mapping

- information architecture and navigation

- content planning

- content production

Let’s unpack how SEO overlaps with each of these key points in the process.

User Journey Mapping

User journey maps are a model of the experience your audience has with your website. If you use them in your current design practice, you know that, first and foremost, these maps try to capture what users are doing, thinking, and feeling at each point along the way.

You can add search behaviors and search intent data to your user journey maps to get a better sense of how search plays into the online bits of the journey during each phase. Not only does this make keyword data more accessible to a larger stakeholder audience, but it also helps you identify steps and mindsets in the user journey that might previously have gone unaccounted for:

- Steps. Search steps commonly appear as a user searching in Google before they reach your website, or returning to Google to compare information. Make sure the way you capture these steps in the journey reflects the user’s intention, too. Were they trying to compare? Research? Validate a decision?

- Mindsets. Other key components of any good user journey map are the thoughts, questions, and information needs users have during each phase of the journey. Keyword data is excellent for identifying this stuff: long-tail keywords are often made up of questions, thoughts, and information needs.

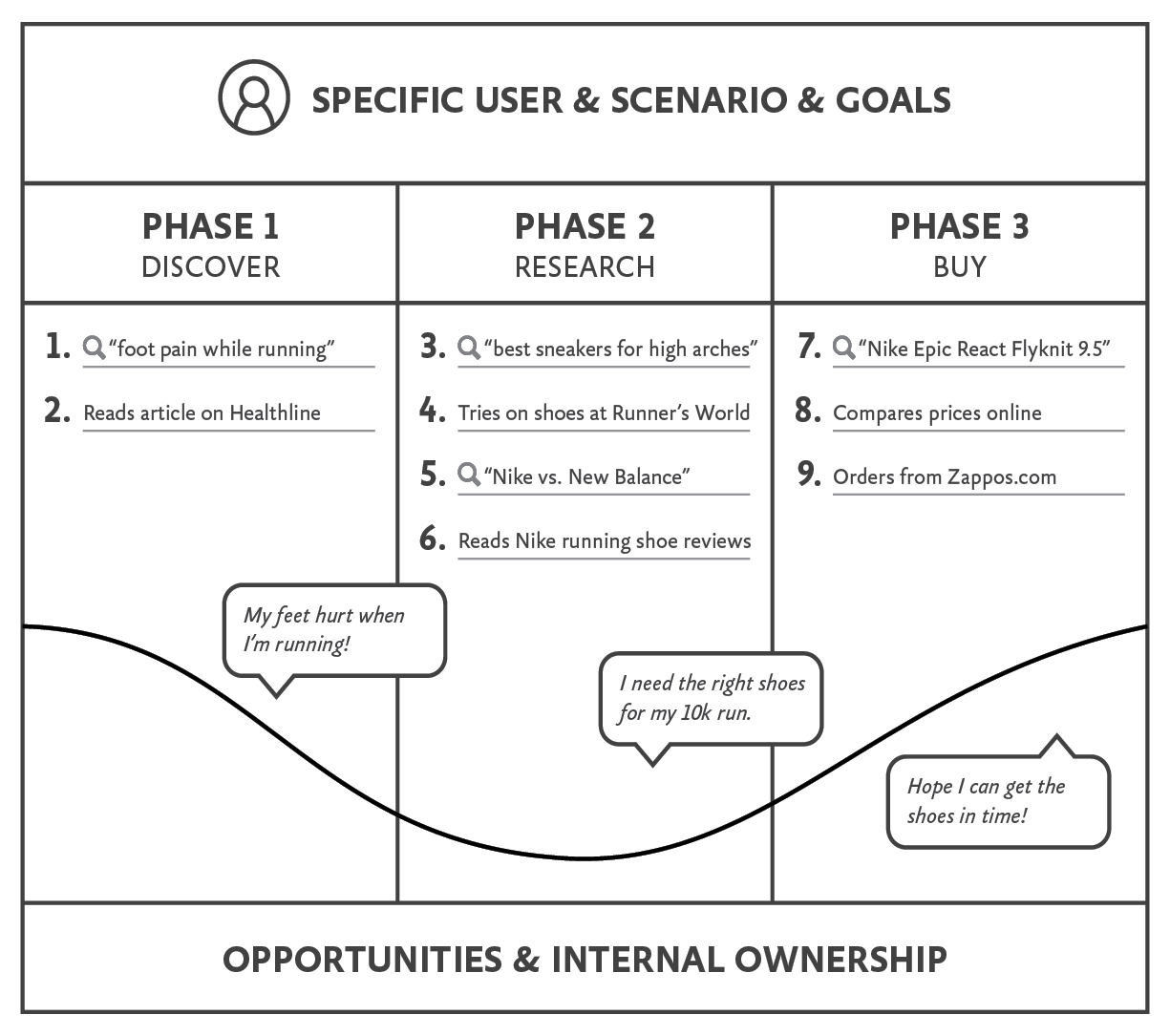

The search steps and mindsets you identify in your research will often correspond with different phases of your user journey maps, but where they land will depend entirely on the phases you’ve defined. For example, imagine a user journey map for an athletic shoe retailer with four major linear phases:

- Discover: the reason for seeking out the product, service, or company—typically “I have a need or problem” searches. You’re looking for keywords and phrases that capture the reason behind the need that drives interaction with your site in the first place. These searches usually express informational search intent and might look like: “feet hurt while running,” “running routines,” or “how to get in shape.”

- Research: the steps users take to define their needs and explore their options. In this phase, you’re looking for “I need to decide among options” searches. Here, the user has defined their need—in this case, “I need new running shoes”—and is looking to compare, validate, or get more specific information. Searches in this phase might include: “best running shoes 2020,” “best running shoes for flat feet,” “Nike running shoe reviews,” or “New Balance vs. Nike running shoes.”

- Buy: the purchase or transaction. Searches in this phase are made up of “I need to find a thing I want to buy” searches. The keywords and phrases tend to be specific: “Nike Epic React Flyknit 2 SE black size 9.5,” “gray running shoes for women,” or “running shoes next day shipping.”

- Support: the post-purchase relationship with the user. Support-related searches are all about “I need help with what I bought.” They sound like this: “Zappos customer service,” “Nike return policy,” or “best way to clean Nike Flyknit shoes.”

While these phases make sense for an online ecommerce journey, your phases might look very different depending on your site’s context and purpose. No matter what phases make up your user journey, they will likely include a mix of offline and online steps. Keyword data can help you better define all the steps and unpack the user’s mindset around them (Fig 4.1).

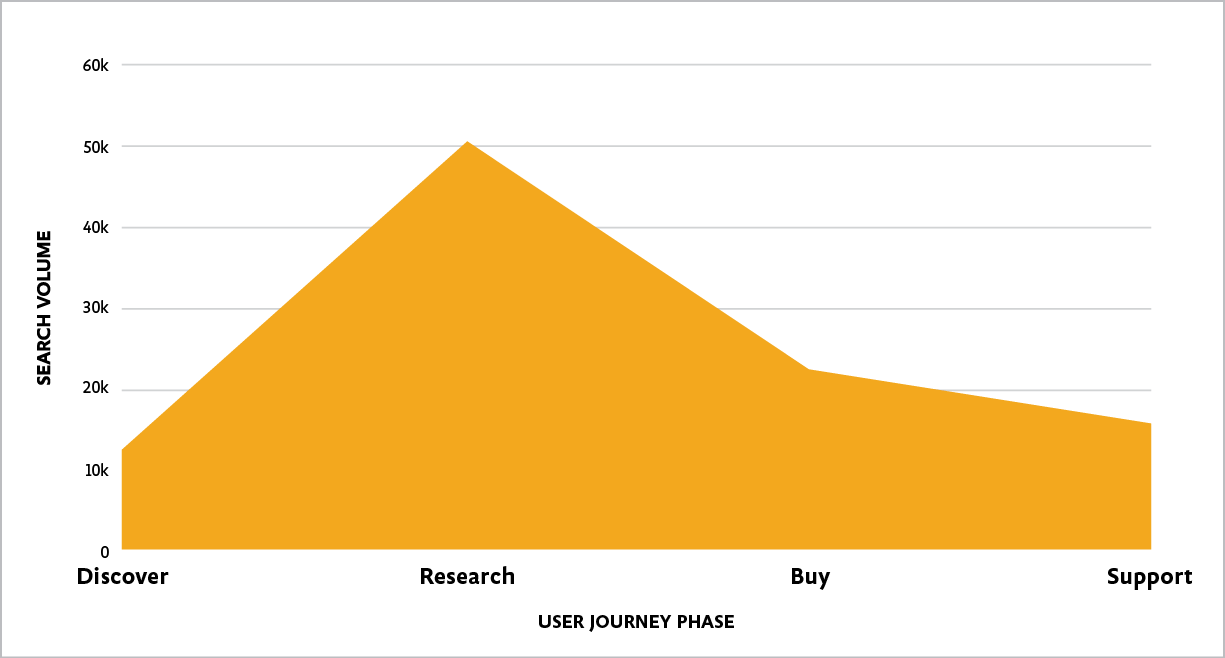

If you really want to get fancy, visualize the search opportunity of each phase by mapping themes of search intent to the user journey. If you’ve done keyword analysis like we outlined in Chapter 2, take your big keyword spreadsheet with correlating search volume and add a new column to map the search terms back to the user journey phase they relate to (Fig 4.2). This will also give you an idea of search volume for each phase. Voilà—you’ve mapped search volume to the journey (Fig 4.3)!

The magic of this step is that once you know which phases of the journey correlate to the highest search volume, you can compare them to the content on your site to identify gaps. For example, perhaps you discover much of the search opportunity around running shoes happens during the research phase. If you don’t have content on your site that satisfies this search intent, you won’t be able to help users find the information they’re looking for. Consequently, you won’t be able to win organic search visibility in that phase of the user journey, either.

Fig 4.1: We’ve pulled actual keyword data from our search intent analysis and overlaid it directly onto the steps of this user journey map, alongside offline actions. The user mindset conversation bubble in Phase 1 was drawn from search data, too. You could make this even more detailed if you quantified the search volume of each keyword you add to the steps.

Fig 4.2: We’ve added a new column (Journey Phase) to our keyword spreadsheet to correlate search data with phases in the user journey. This isn’t an exact science; we’re taking our best guess at which phases the keywords naturally match, which helps us quantify search opportunities.

Fig 4.3: Identify potential content gaps by comparing phases with high search volume to existing site content and the traffic in those related site areas.

Information Architecture

Information architecture (IA), the practice of “organizing, structuring, and labeling content in an effective and sustainable way,” is the foundation of good usability (http://bkaprt.com/seo38/04-02). The goal of IA is to make sure users can find information easily and complete the tasks they came to do. Coincidently, this sounds a lot like the goal of SEO.

Essentially, IA underpins your entire content ecosystem: what will be on your site, where it will live, and how each page will be labeled. Not only is IA valuable for search visibility, but what something is named in the navigation also communicates its semantic relevance to Google.

When it comes to SEO and IA, there are a few things you must consider as you go about your business.

To page or not to page

If you don’t have clearly organized and labeled content around something, it will not rank. Creating a dedicated page with helpful, relevant, and unique content on a given topic will boost that topic’s search visibility and ranking—and it will serve your audience. If the page doesn’t serve your user, it might not be worth creating.

Creating pages purely for SEO is never a good idea. As Sarah Winters of Content Design London says, “If you think about SEO purely being for the human searching for information then you wouldn’t get ‘SEO pages’” (http://bkaprt.com/seo38/04-01). As you determine whether or not you need a new page, some questions to ask yourself from an organic search perspective include:

- Is there a product or service that needs to be represented? There should always be a page dedicated to each individual product or your organization’s core offering.

- Is the information critical? Think of content like a return policy, legal notice, or code of conduct—it might be brief, but because of its essential nature, it needs to be easily found.

- Is there enough to say about the topic? Topics that are relevant to your business goals and user needs will naturally generate content. If you don’t have much to say about something, that suggests you don’t need to create a dedicated page.

- Is there too much to say? When you have a lot to say about a topic, breaking your content into shorter subpages might better align with ways people search for that information. It makes the information easier to find in organic search, and easier to navigate and digest onsite, too.

Ultimately, the pages you create are for real people who are trying to find your subject matter. The content must always be designed to meet their needs.

Follow your users’ leads

While working on a site redesign for one of the oldest and most respected speakers’ agencies in the US, we learned that most users looked for a specific type of speaker for their event, one they had already determined would be a good fit. The search data revealed, not surprisingly, that the two most popular ways people searched for speakers were by topic—“conference speakers on healthcare and medicine,” for example—and by type—“women keynote speakers”—or a combination of both. But we also learned that leadership wanted to use the top navigation to showcase their “about us” page, which focused on their reputation, exclusive speakers, news, and curated programming ideas. This buried the speaker categorization and search filters several pages deep in the site’s structure. They weren’t considering what users wanted in the nav; they focused on what they wanted. This is how it had always been; this was what the agency’s leadership felt the most comfortable with.

But leaving the topical speaker search out of the main navigation would have been a missed opportunity from an organic search perspective, and it would have made it harder for people to complete their primary task.

Thankfully, the search intent data was compelling enough to change leadership’s mind. They ultimately included speakers by topic in the main navigation and made sure the ability to filter speakers by topic and type was an omnipresent search option (Fig 4.4). Furthermore, we were able to identify exactly which speaker topics and types were most popular in terms of search volume and made sure those were listed first in the navigation and filtering options.

In her book Everyday Information Architecture, Lisa Maria Marquis says, “Look for the words (especially the verbs!) that people use when interacting with your site or product, then mirror their language back to them.” For this site redesign, the words people used in their searches not only informed category labels; they also implied a larger task that needed representation in the navigation to fully satisfy search intent.

Whether you organize information using an exact system (chronologically, alphabetically, or geographically) or subjectively (by topics and tasks), you can study search intent data and listen for clues in user interviews to see how people search, and then use this data to make better information architecture decisions for your site.

Use content hierarchies to show relationships

The way content is categorized and subcategorized can help pages improve in search results. This is true for high-level topics that correlate to more general search terms, as well as for specific subtopics that correlate to long-tail search terms. The key here is that both types of pages need to link to each other (Fig 4.5). High-level category pages must contain links to their subcategories, and pages within the subcategories should link back to the parent category.

This tells search engines that the pages are related in terms of subject matter. Pages with high link authority pass equity along to linked pages. This means that where content is subcategorized directly impacts the ranking ability of its parent category. Although the purpose of categorizing content is to make it easier for people to find what they’re looking for, don’t forget about the signals you’re sending to search engines. How you subcategorize content will impact what topics you do or don’t gain search visibility for.

Breadcrumbs are beneficial

With organic search, any page in your site can be the first place a user lands. Breadcrumbs and navigational highlights help users orient themselves within your website and understand how the page they’re on relates to a higher-level category. Beyond the UX benefits, breadcrumbs also serve as an internal linking structure that gives search engines a better understanding of how your pages are contextually related to one another. Google now displays breadcrumbs in search results and uses them to categorize information on the SERP as well.

Harness the benefit of breadcrumbs by making sure they’re near the top of the page and visible when the page loads, and at every screen size (not just on desktop). Since Google primarily crawls your site from a mobile perspective, you’ll need those breadcrumbs on smaller screen sizes in order to provide clear connections between various categories of content (Fig 4.6).

Fig 4.6: To save space on small screens you could remove the homepage link and use truncated breadcrumbs, as MetLife does here.

Subdirectories over subdomains (and microsites)

Where content lives impacts not only the user experience, but also search visibility—and link authority plays a role here, too. Link authority consolidates more value (and gains strength) when high-value pages live under one domain rather than being spread over multiple domains or properties.

Getting IA right means considering three things: your users’ needs (particularly around understanding and navigating content), your brand strategy, and search intent. We suggest addressing these decisions in that order; you can’t force what’s best for SEO if it doesn’t align with brand strategy and actual user needs.

Alas, many organizations don’t take any of these factors into account in their decision-making; they simply do what’s easiest for the business, like creating microsites and subdomains. Establishing a separate property is often easier than changing the existing site structure to accommodate new content. However, even when owned by the same organization, microsites and subdomains are viewed by search engines as discrete properties where trust and authority must be built from scratch. Linking to this off-site property from the main site can help, but it can’t perform as well as it would if located in an existing site subdirectory. Creating a subdomain or a microsite isn’t always the wrong answer, but consider the costs to organic search and user experience before you make a final decision.

URL structure

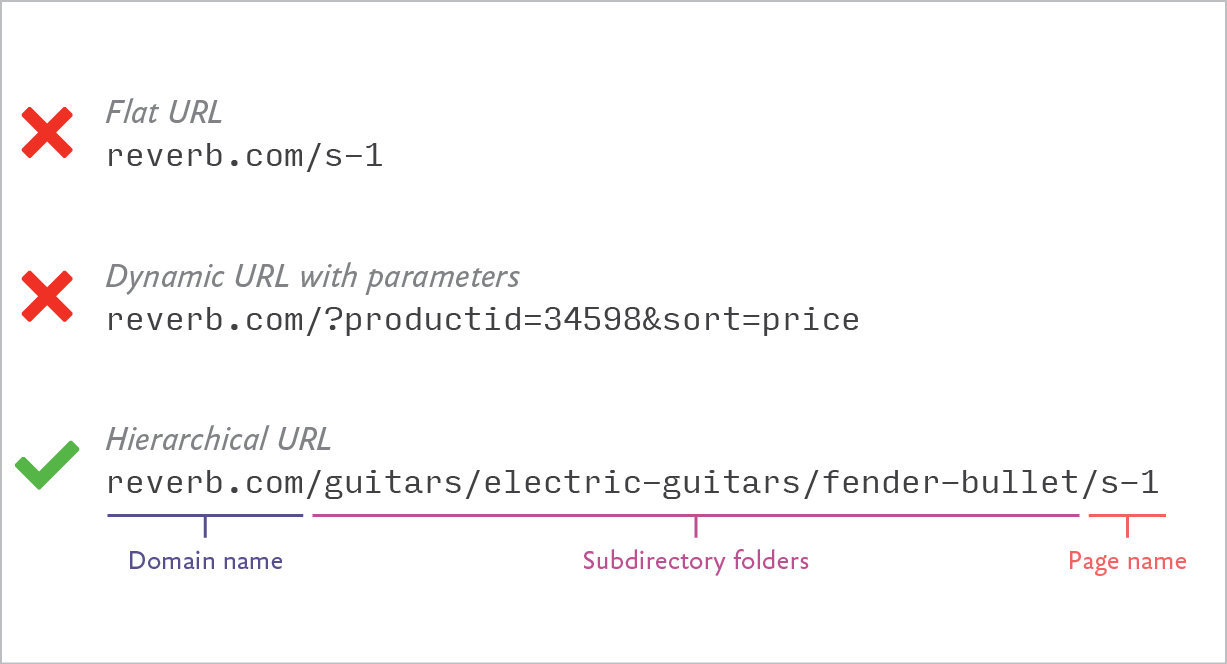

The humble URL plays a key role in establishing a first impression for both users and search engines: it helps them understand site structure and get a sense of where they are in your site. URLs that reflect a clear folder or site structure path are the most effective for both user experience and SEO.

A few things to consider when it comes to URLs:

- There should only be one URL for any given page. Avoid multiple URL variations that lead to the same page.

- URLs should start with your domain name, followed by the section name, then the next subsection name, until you reach the subdirectory where the web page is located, appearing as a sequence of segments in hierarchal order separated by slashes. Using a flat URL structure, where the URL doesn’t contain any of the directory folder sections, is a missed opportunity for usability and SEO. It also makes it harder to track section performance analytics.

- Aim for clarity and human-readable language. Avoid using dynamic parameters; stick with alphanumeric characters that have semantic meaning (Fig 4.7).

- The directory and subdirectory folders should reflect the taxonomy of the site for clarity and consistency. Please note that no matter what you hear about SEO, directory and subdirectory folders are not the place for one-off “keyword” opportunities. If your site taxonomy is semantically relevant, your URLs will be, too.

- When it comes to optimizing the URL slug (the part of a URL that identifies the specific page), do try to include the main keywords you’re trying to gain visibility for. In terms of length, shorter is better than longer; save space by removing conjunctions and prepositions like “to” and “and.” Use hyphens between words for readability.

Fig 4.7: A flat URL structure won’t do you any findability favors. Neither will dynamically generated URLs that aren’t semantically relevant. A hierarchical URL naming structure, on the other hand, tells both users and search engines about the page and its location in the site.

Navigation design

Navigational structures—the main menu, subnavigation, and footer—are the core of what’s known as internal linking structure, or all the links between your web pages that establish relationships between content and site architecture and spread link equity. Search engines use your website navigation to discover and index new pages.

While your first priority to users should always be ensuring clarity, here are some things to keep in mind when it comes to SEO:

- How you assign visual priority to links helps determine how link authority, or what Google calls PageRank, flows through your site to those pages. In practice, this means links in the footer typically carry less authority than main navigation links, while a bolded text link on your homepage might carry more weight than a link several clicks deep in the main navigation. Make sure pages that need to perform well in organic search are placed prominently and are designed to stand out, can be found easily, or are seen first as a user scans through the page (http://bkaprt.com/seo38/04-03).

- On parent pages containing a list of results, like a blog page with a list of articles or a product category page with a product list, the order in which you list those results shows priority to search engines. When you want pages to rank highly in search, they need to show up on the first page of their parent category pages (not buried somewhere deep within your website).

- Make sure the full functionality of the navigation is available regardless of screen size. Don’t truncate the navigation anywhere, even in the footer. Google uses your site performance on mobile devices to determine ranking for everything, so it hurts both SEO and user experience to provide a lesser experience for smaller screens. This means that you shouldn’t focus on the desktop experience at the expense of how your site loads on mobile devices or its usability on small viewports. A device-agnostic approach will serve you and your users best.

- Google will view pages in your site linked to by other reputable sites as more authoritative. For many sites this is simply the homepage or other pages in the main site navigation. When it makes sense, linking to the most authoritative pages in your site helps distribute authority to the rest of the site. Typically, the farther pages are from the most authoritative pages, or the farther they are from pages linked in the main navigation, the less ranking power they will have.

Done right, navigation design will make it easy for folks to find what they’re looking for and send crucial signals about the priority of content on the site to search engines. Ultimately, it’s important to be intentional about your search priorities and to make design decisions that reflect them.

Content Planning

Content strategist Ida Aalen, writing about Are Halland’s core-modeling process, said:

If you’ve worked on a website design with a large team or client, chances are good you’ve spent some time debating (arguing?) with each other about what the homepage should look like, or which department gets to be in the top-level navigation—perhaps forgetting that many of the site’s visitors might never even see the homepage if they land there via search. (http://bkaprt.com/seo38/04-04)

The same can be true when it comes to determining what content, features, and functionality will go on nearly any web page, because it means actual people have to agree on priorities. And actual people have a tough time agreeing on much of anything, especially when it comes to competing UX and SEO goals.

Luckily, human-centered SEO and UX goals should never really conflict with one another—but if your colleagues aren’t in alignment, a collaborative core-modeling exercise can help get all your content and design stakeholders on the same page (pun intended). Inspired by Aalen’s recommendations and Halland’s core-model template, but adapted to incorporate search considerations, we use this exercise to plan web content for our projects (Fig 4.8). You’ll need to invite a cross-disciplinary team consisting of content stakeholders and content and design implementers to work together to core-model the page.

While we recommend reading Aalen’s full article first, let’s walk through the steps we take in the core model exercise:

- Identify user tasks in search data and balance them with findings from other research.

- Determine the role search will play in meeting the page’s business goals, translating those to search goals.

- Choose content elements and determine information hierarchy of the page.

- Consider internal linking structures.

Identify user tasks

The first order of business when it comes to planning what content will live on a page is asking, “What is it that people want to get done?” Look to both your search intent analysis and any other relevant user research you have to identify all the tasks users are trying to accomplish on the page (not just search-related); then, order them from most important to the user to least important.

For example, imagine you’re planning content for a page on pregnancy and childbirth on a health insurance website. After reviewing search intent analysis data, you might make notes around the themes of intent like:

- “breast pump covered through insurance”—2k searches per month

- “best health insurance for pregnancy”—1k searches per month

- “health insurance for pregnancy no waiting period”—1k searches per month

Reimagine the search terms as user tasks by restating them with an active verb, like this:

|

Theme of Intent |

User Task |

|

|

“breast pump covered by insurance” |

becomes |

Learn which plans cover breast pumps |

|

“best health insurance for pregnancy” |

Read reviews from expecting parents and see ratings for our health plan |

|

|

“health insurance for pregnancy no waiting period” |

See coverage and plan waiting-period details |

Using search queries to identify user tasks and their correlating search volume to estimate priority helps ensure search intent influences content and design as early on as possible. However, as you may remember from our discussion of long-tail keyword data in Chapter 2, even the most popular keywords on a specific topic are no match for the search volume of long-tail keywords related to that topic. So, while the keyword volume for “breast pump through insurance” only amounted to two thousand searches per month, in aggregate, all long-tail searches with this intent might add up to something much more substantial, like fifteen thousand. This is why search volume for individual search phrases can be misleading. It’s a good idea to scan your full list of keyword data around a theme of intent and get a sense for which themes have greater volume, or, better yet, sum up the search volume for each theme of intent.

Once you’ve organized your keyword data by themes of search intent, you can sum up the search volume of each theme and its subthemes to estimate the number of people searching for those intent topics and prioritize the user tasks you identify accordingly. For example, using pivot tables, we can sum up the themes of pregnancy-related search intent, which makes it possible to see percentage data and helps prioritize user tasks. We list all of the corresponding user tasks for search intent data points alongside any other user tasks identified in other forms of research, too, like user interviews or surveys:

|

Search Intent Data |

All User Tasks |

|

Out of seventy-five thousand searches per month: |

Users want to: |

|

27 percent are looking for waiting-period coverage details |

Understand the waiting period |

|

24 percent are looking for health plans that include pregnancy coverage |

Find out how my pregnancy medical expenses will be covered by your health plan |

|

17 percent are looking for information on breast pump coverage |

Find out if my breast pump is covered under your health plan |

|

10 percent are looking for details on pregnancy coverage while traveling |

See what covered birthing facilities look like and the features they offer See if my preferred hospitals and doctors are in your network |

|

8 percent are looking for validation, such as reviews, awards, and ratings |

Read reviews and customer ratings |

|

8 percent are looking for cost information |

See coverage details Get a quote Sign up for your health plan See if alternative birth centers are covered under your plan Understand the breakdown of average covered costs and how much my part will be |

Remember, this isn’t an exact science. You’ll need to use your best judgment to balance tasks without data, like the ones you have from interviews or surveys, against tasks identified in search intent to best serve your users (and meet your business goals).

Determine your search goals

You’d be surprised how many organizations don’t have clear search goals for their site beyond “get more traffic” or “increase conversions.” It’s even less common to see thoughtfully planned out search goals at the page level. But knowing exactly what to expect from organic search for an individual page, and how it will help achieve business goals, is the only way to avoid chasing vanity metrics.

Although some goals for the health insurance maternity page might be directly tied to search, like “Get organic search visibility for pregnancy health insurance-related terms,” others will simply be business goals, like “Help existing plan members learn more about maternity and childbirth coverage and plan options,” or “Increase requests for quotes and leads by 15 percent.” Use this to discuss how organic search can play a role in helping achieve the page’s business goals, and how you will measure its contributions.

Start with the prioritized, measurable business objectives and subobjectives for the page. What does your organization want to achieve with this page? Once known, you can map those objectives back to specific actions or outcomes you can measure in analytics and attribute to organic search. For example, let’s look at how business goals for a health insurance website might translate to search goals:

|

Business Goals |

Search Goals |

|

Generate leads from quotes. |

Increase the number of quotes generated from organic search traffic. |

|

Connect with people shopping for health insurance for pregnancy. |

Rank for “health insurance for pregnancy”-related searches. |

|

Get organic visibility for “health insurance for pregnancy”-related searches. |

This doesn’t need any translation, since it’s already clearly tied to search. |

|

Help members understand their pregnancy benefits. |

This doesn’t translate well to organic search, since most existing members would visit the site directly to log in to their account or browse the pregnancy page. |

|

Position ourselves as a leader of pregnancy-friendly health insurance. |

Increase organic traffic visits to the blog from the pregnancy page. |

Clearly, someone on the team with a little SEO or analytics experience can help with this part. But with a little search knowledge (hey, you’re reading this book, right?) and determination, anyone can map business goals to search metrics. We challenge ourselves to list no more than four to six business goals for a single page—more than that, and it becomes hard to effectively work toward any goals.

Inevitably, you might find the business goals you identified and prioritized in the exercise don’t directly correlate to user tasks, or, if they do, they might be out of alignment in terms of how you prioritized them. It’s not unusual to see business goals for a page that don’t map back to any user tasks! Or to see the top priority for users rank at the very bottom of the priorities for the business. That’s natural. This exercise is designed to help your group of stakeholders identify misalignments and either realign the business goals to better serve the user’s needs or make conscious compromises around them. A conscious compromise involves intentionally choosing to prioritize what we want over what users want. (This is clearly not ideal, but at least we can be honest about it and set realistic expectations.) Visualizing these misalignments can be a powerful tool for driving more user-centered design choices.

Choose content elements

Now that you’ve thought through and prioritized user search goals and tasks, as well as your organization’s search goals and general business goals for the page, determine the copy, videos, images, tools, or other elements that will make up the page—and decide what order to present them in.

Have the team list all content they think the page needs to help users accomplish their tasks and your organization achieve its goals, and brainstorm any features or functionality needed to support that content.

Continuing our example of the pregnancy and childbirth page, you might list content elements like this:

- Images of pregnant people, photographs of relevant birthing centers, and pregnancy-related illustrations

- Headline that speaks to “Health Insurance for Pregnancy and Childbirth”

- Brief introductory copy explaining the main benefit of health insurance and outlining what information the user will find on the rest of the page

- Call-to-action banner encouraging readers to get a quote or contact an agent

- Quoting tool or form and submission button

- Content block explaining the waiting-period policy and links to the member login for more in-depth coverage details

- Content block about coverage for breast pumps and lactation consultants with a link for members to log in and explore covered pump options, find covered lactation consultants, or file a claim

- Content block focused on birthing center options, with a mention of both natural childbirth and cesarean birth options

- Graphic illustrating average pregnancy-related medical expenses with health insurance

- Video and text testimonials from members who had their maternity care and childbirth covered by our health plan

- Links to articles on pregnancy and childbirth on the blog

- Links to information on newborn insurance coverage, insurance for pediatric care, and the process of adding a newborn to your health plan

Once you’ve listed all potential content elements for the page, go back and consider the prioritized business goals and user tasks, and then rank the content elements from most to least important. Imagine a user is scrolling through the page on their phone. What’s going to show up first? And then next? And then next? All the way down the page.

Whether you’re doing this in person with sticky notes, working in a Google doc, or using some kind of online whiteboard collaboration tool, be aware that quite a bit of conversation, even arguing, usually happens during this step. It’s common for folks to disagree about which content elements come first, or how best to address the user tasks. It can get rowdy! And that’s exactly what you want: people hashing out how they’ll address priorities and satisfy search intent now, in the content-planning phase, instead of making expensive page-template changes during development or writing content too close to launch.

What’s the best way to do this? Have the team work together to arrange the content elements in a single-column layout (Fig 4.9). This forces you and your colleagues to prioritize content, and keeps you focused on content needs rather than on designing elaborate multicolumn layout scenarios, or derailing conversations with visual design decisions.

Consider internal linking structures

Finally, you’ll determine the forward paths, the links to where people will go next. These links are essential to the core model’s success and should always be considered in the context of the user tasks (and search intent) for the page.

In addition to thinking through general forward paths—like where you want to send the user next, or what documents, downloads, or contact information might be helpful—you’ll want to consider how these forward paths impact search visibility. You’ll recall from Chapter 3 that forward paths help Google better understand your website overall and the relationships among content components across the site. Forward paths also help Google understand the volume of content and authority you have on a certain subject.

To continue our example, the pregnancy and childbirth page could link to blog posts on pregnancy, articles about childbirth, and coverage details on health insurance for newborns. These forward paths would help search engines better understand the connections between those different types of content and provide users with useful, relevant next steps at multiple phases in their journey.

At the end of this exercise, you should have a clear design artifact that you can use to plan web writing, and that will serve as a foundation for wireframing and template design. Ultimately, this exercise should be equal parts content, design, and SEO—an essential tool for bringing all three together effectively and ensuring search intent will be satisfied before writing even begins.

Schema.org Markup Elements

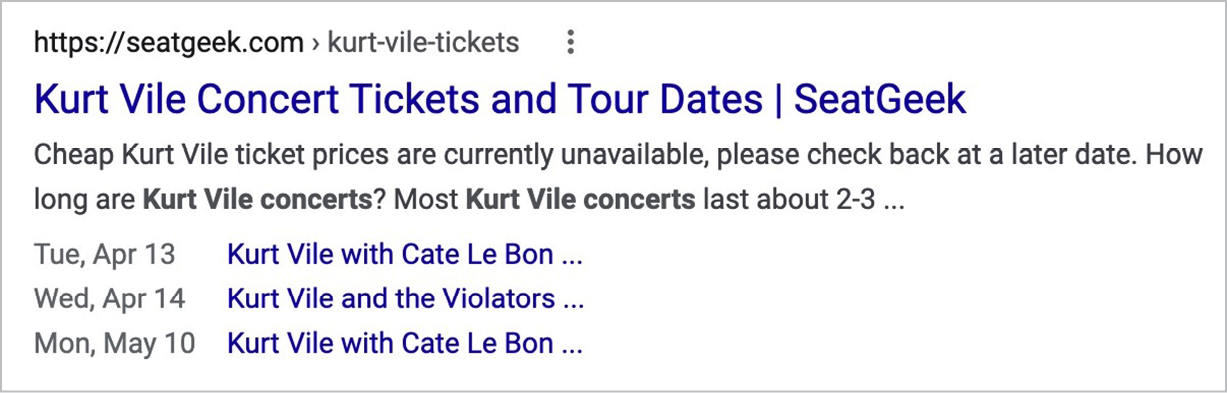

Schema.org markup, also known as structured data, is a data vocabulary used by all major search engines for information related to creative work, events, organizations, people, places, and products—as well as different content types such as video, images, or audio. Hundreds of term types let you describe products, publications, local business listings, restaurant menus, and all sorts of industry-specific concepts. While not an official ranking factor for Google, the additional context it provides allows the search engine to show a page in a more relevant context—helping it rank for the right terms (http://bkaprt.com/seo38/04-05).

Beyond communicating data and metadata to Google efficiently, certain types of Schema.org markup can change the appearance of your search results, making content appear on the SERP as starred reviews, product cards, event cards, and more (Fig 4.10).

Fig 4.10: SeatGeek uses event markup that helps concerts from our dude, Kurt Vile, listed on its site show up as sublistings under the main page listing on the SERP.

Markup like this helps users better understand what content they can expect from a search result, get answers to their questions more easily, and click through to the most relevant page for their interests (Fig 4.11).

Schema.org properties and content elements

You can only include details in your markup that exist as real details in your web content. This means Schema.org optimization starts with content planning. You need to account for the right elements in your content and page templates in the design phase, before things go to development. For example, if you want those sparkly review stars next to your SERP listing, you better have actual third-party reviews on your product page. Beyond having authentic reviews and choosing a reputable third-party review platform, you’ll also need to account for how the reviews will be incorporated into the page’s design. If you look into the schema types, you’ll see the list of elements to mark up has to agree with the list of content you need to include for those page types (Fig 4.12).

A word of caution: if you treat this as an afterthought and try to optimize for properties that don’t exist in the web content later, your site will get slapped with a penalty from Google (http://bkaprt.com/seo38/04-06).

To get started with Schema.org on your site, research which markup types and properties apply to your content as specifically as possible (http://bkaprt.com/seo38/04-07). Get as granular as you can. Once you determine which Schema.org types apply to your site, explore the content properties for each markup type you’re using (Fig 4.13). For example, if you wanted to add Schema.org terms to a web page about a book, you would look at the Book type and apply properties like these:

author, to mark up the author of the booknumberOfPages, to mark up the number of pages in the bookdatePublished, to mark up the publication date

While you have to plan which Schema.org elements you need to include in your content now, in the design phase, Schema.org markup is implemented later on, during the development phase, using JSON-LD in the head of the page. If you’re not code-savvy, ask for help from someone in your organization who is. We provide some tips on how to implement this markup during development in Chapter 5.

Fig 4.12: These are the Schema.org elements for a person’s bio. If you plan to use Schema.org markup for bios on your site, you can use the list of properties in the column on the left as a sort of bio content checklist. Choose applicable elements and include them in your content outline.

Fig 4.13: This is what Schema.org markup for Erika Hall’s Just Enough Research on the A Book Apart website would look like if implemented.

Content Production

Once you’ve planned content for your page and considered content presentation formats, it’s time to tackle the actual writing and on-page optimization. Take heart: having a well-thought-out content plan to address search intent is the hardest part! Now you need to bring that plan to life and make a few search considerations along the way.

As with most aspects of human-centered SEO, there’s never really a reason to do something just for search engines. SEO is about making things findable for humans, and your web writing and on-page optimizations should reflect this. Here’s what to consider when getting your content is ready for prime time.

Incorporate keywords (on-page SEO)

Even though satisfying search intent is the most important thing you can do, you’ll still want to set both primary and secondary keyword targets for your page.

Primary keywords are the high-volume, most commonly used search terms that correlate to your high-level themes of search intent. Secondary keywords are the high-volume, most commonly used search terms that address all the forms of subintent your page addresses. Google’s ability to understand synonyms and conceptually related phrases has improved greatly in the past decade, giving us the freedom to use natural language without obsessing over keyword variants (like plurals). This step leverages keyword data to learn more about what language makes the most sense to users and strategically using those terms to optimize on-page elements.

Here are recommendations for incorporating keywords into your content:

- Use primary keywords in the page title, meta description, and main headline (

h1tag) of the page, and in the first few sentences of page copy. - Use secondary keywords in

h2andh3tags—for subheadings or section titles that address subintent. - Be natural. Even when using keywords, write things the way a real human would say them.

- Keyword density doesn’t matter, so don’t be repetitive if you wouldn’t naturally say things more than once.

- Use your search intent research or go back to your keyword research tool to see the most popular ways people describe your products, services, or information, and mirror their language back to them.

Above all, don’t focus on using keywords above satisfying the search intent. Your content will need to answer all forms of intent and help users complete their task or solve their problem—regardless of keyword optimization.

Write good meta descriptions and page titles

When you think about the high-priority steps of a user journey, you might think of the homepage or key product pages, the site navigation, or the checkout flow. And you’d be right—these are pivotal moments. But as we’ve discussed, a good user experience actually starts at the search engine level, where a title and meta description are the only thing between the user and your site.

For example, take a look at the rather soulless meta description on Tempur-Pedic’s homepage (Fig 4.14). See how the title is truncated and devoid of personality?

Fig 4.14: Sure, from this we can tell that Tempur-Pedic sells mattresses and “sleep systems” (whatever that means), but there’s nothing to pull us in. Its keyword-crammed description doesn’t look like it was written by a real person, and the generic “limited time offers and promotions” is vague.

Now, compare that to the meta description from another mattress purveyor, Tuft & Needle (Fig 4.15). This time, the headline isn’t truncated (it contains just the right amount of text). Furthermore, beyond using the keyword “bed,” they add some personality with “honest bed products” and make a bold claim to “reinvent sleep.”

The lesson here? To do their job and win the user’s click, good titles and meta descriptions must go beyond keywords—they have to be compelling, relevant, on-brand, and helpful. (Keep in mind that click-throughs, over time, can have a positive impact on your ranking overall.) Here are a few guidelines to keep in mind when writing titles and meta descriptions:

- Stick to the character counts. Both the title and meta description will be truncated on the SERP if you go over the character-count limits. That’s around sixty characters for page titles, and up to 160 characters for meta descriptions.

- Include keywords. As discussed in our on-page SEO recommendations, use primary keywords in both the title and meta description whenever possible.

- Address key search intent. Make sure your meta description aligns to the key search intent and clearly communicates how your page will help the user achieve their goal.

- Treat the page title like a headline. Good headlines don’t just describe—they also grab attention, create curiosity, and take a stance. So put on your copywriter hat and craft a page title that stands out.

- Be specific and honest. While you want the meta description to be compelling, you don’t want to overpromise and underdeliver, or cause confusion by being vague. This can prompt users to hit the back button because they didn’t find what they thought they would get based on the description they read. In turn, this could end up hurting your performance metrics over time.

- Don’t overlook brand voice and tone. Is your brand voice bold, practical, or witty? Does your organization use specific words to describe how your products look, sound, or feel? Meta descriptions, especially those for important, highly visible pages, are places to let that brand voice shine. Be sure to apply any writing guidelines to these.

All right, we’re done waxing poetic on titles and meta descriptions. Just remember: meta descriptions and title tags for key pages deserve just as much attention as carefully crafted copy on the homepage.

Optimize your images

Images can help convey meaning and, in some cases, satisfy search. A recent study from Jumpshot shows that 20 percent of organic searches consist of Google image searches alone (http://bkaprt.com/seo38/04-08). This shows how important it is to optimize your images for search performance, especially for in-content imagery (as opposed to hero banners or background images). When choosing and preparing images for your site, you should:

- Use semantically relevant file names for the images. For example, if you have an image of an apple tree, the image file name should be something like apple-tree.jpg, instead of img129.jpg.

- Avoid generic stock images that don’t contribute additional meaning to the content. Choose specific images that enhance the text content and can be clearly described to both people and search engines.

- Write descriptive alt text, captions, and copy related to the image, incorporating keywords when appropriate (they should read naturally).

- Look for ways to add value with a helpful chart or diagram when appropriate, since these can help earn visibility in image search results.

- Make sure images are formatted for the web and won’t slow down page-load times.

Format for scannability

Nielsen Norman Group (NN/g), which has been running web usability studies for decades, has found that users “scan the pages, trying to pick out a few sentences or even parts of sentences to get the information they want” (http://bkaprt.com/seo38/04-09).

Although we don’t think NN/g’s assertion that “users do not read on the Web” holds water, we do think it’s absolutely true that users scan pages and jump to certain points in the text that align with their interests. Making it easy for people to quickly scan a page and find the information they’re looking for is important for search because it means your page has a shot at satisfying their search intent. Otherwise, they’re apt to return to Google and search for another page that’s easier to read—which ultimately hurts your search rankings.

Here are some of our favorite ways to make content easy to scan:

- Use detailed, descriptive, and accurate headlines to communicate topics immediately.

- If the page is long, use anchor links to give readers an idea of what the page contains and enable them to jump to relevant sections (Fig 4.16).

Fig 4.16: Not only does Healthline make good use of anchor links for a long article page, but it’s also clearly on top of researching search intent. These sections are ordered nearly exactly from most to least important search terms. - Highlight critical content in callouts, quotes, or asides.

- Increase the size of heading text appropriately in comparison to the surrounding text. The main

<h1>heading for the page should be the largest, making the page’s main topic obvious to search robots, screen readers, and people.

Showcase expertise

It’s ideal for site content to be written by someone with subject-matter expertise, especially when it comes to more nuanced or technical matters. To Google, an author’s expertise and verifiable credentials are particularly important for content that impacts people’s well-being (http://bkaprt.com/seo38/04-10). Sometimes referred to as Your Money or Your Life (YMYL) content, these topics include news, health, medicine, finance, government, and law, as well as identity issues like ethnicity, religion, disability, gender, and sexual orientation.

Always identify the authors of articles or editorial content on your site. List their credentials, and link to their biographical content, additional publications, connections with other organizations, and social media accounts.

Stay fresh

Fresh, from a search perspective, means content published or updated recently or frequently. Freshness matters to Google—just like it matters to people—when the information is time-sensitive and can impact its relevance, as with news, scientific research, financial advice, and event information. A study published in May 2020 found that “not only do pages where the majority of content changed get crawled more often, but those pages also rank for more keywords” (http://bkaprt.com/seo38/04-11).

This means that part of on-page optimization is keeping content current and updating date-sensitive content as part of your ongoing governance plan. Keep a site inventory spreadsheet containing every URL on your site. Use it to document when pages were last updated (your CMS may allow you to run a report by URLs and their last modified date), make a note of any date- or time-sensitive pages, and plan to update them at regular intervals. This could be quarterly, annually, or even monthly or weekly depending on the context and date relevance of your content.

Adapt voice-and-tone guidelines

Your organization might have guidelines for your brand’s voice and tone. Often, these determine the words and phrases your copywriters can use to describe products or services. Such guidelines are excellent for standardizing brand expression, but if they don’t take search intent research into account, they can accidentally hinder search and user experience.

For example, our life insurance client ran into trouble aligning their web copy with search intent and user-friendly language because the brand team had developed rules concerning how they would, and would not, describe their insurance packages. According to the guidelines, writers were required to use the term voluntary benefits rather than supplementary insurance, which search intent research showed was used far more by customers and potential customers. The brand guidelines were in direct opposition with how people searched—a real problem for search visibility. A little collaboration between the SEO and brand teams would have resulted in a more effective set of voice-and-tone guidelines that align with the way users actually describe products.

To avoid setting brand guidelines that sound nice but conflict with real user language, use search intent and popular, high-volume keywords as a guide in developing voice and tone. Take it a step further and make sure guidelines go beyond web content, so all marketing copy can reflect consistent, user-friendly terminology, both online and off.

Make It Multidisciplinary

By now it is probably obvious that SEO is multifaceted and extends well into information architecture, site navigation, content design, links, images, URLs, and beyond. In the next chapter, we’ll talk about some of the more technical aspects of search optimization and discuss how to make sure all the SEO considerations you’ve put into content and design carry through into how a site is developed.