Chapter 5

A Decision-Based Life Cycle For Improvement

You may wonder why, with all the various approaches to process improvement, we’re adding another. Not surprisingly, we actually have different, but similar, reasons.

SuZ: I’ve always been a “try before you buy” consumer. Most process improvement life cycles I’ve used or read about make the assumption that you’re ready to dive right in and “buy” both the concepts of the model they’re using and their approach to dealing with the main issues we talked about in Part I. I don’t believe that’s always the best way to approach process improvement. So the life cycle presented here, called DLI, lightens the load on up-front investment in infrastructure so that you can try process improvement with your chosen model before you make a large commitment to infrastructure building, sponsorship, and appraisal.

Rich: I believe the agile software developers have the right idea when it comes to accomplishing a task and, as Martin Fowler says, “delighting the customer.” Process improvement is like any other process or service in that it needs to meet the customers’—or, in our case, the sponsors’—needs. And like most customers, very few sponsors know exactly what they want right off. It’s up to the PI team to anticipate, listen, and learn as they go. Most PI life cycles, although providing mechanisms for feedback, are rarely implemented that way because the feedback is not intentional within the process. I think DLI does a good job of balancing process and flexibility, and gives the organization the best opportunity to maximize the business value of PI.

In some ways, approaching PI is akin to trying to find the right map to use. Some maps provide one kind of information—a general lay of the land and some particular points of interest (Figure 5-1).

Others, as shown in Figure 5-2, provide different kinds of information—more of a navigational routing.

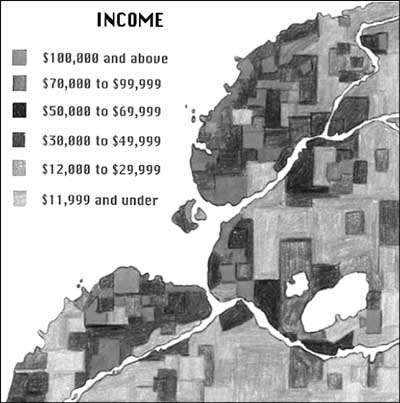

Still others provide specialty information of interest to a specific group: income demographics, as depicted in Figure 5-3.

What we’ve tried to do with our Decision-based Life Cycle for Improvement (DLI) is provide one of these “specialty maps,” not as focused on the navigational routings as on presenting the map from a specialty viewpoint: the viewpoint of what decisions you are likely to face as you engage in your improvement effort.

Figure 5-1: Points-of-interest view

Figure 5-2: Navigational routing

Most process improvement life cycles focus on the activities that need to be accomplished. What we’ve observed is that process improvement, especially at the beginning, is even more about making decisions than just performing activities.

DLI is a life cycle based on a decision-implementation model (Figure 5-4) that we’ve found useful for framing many kinds of technology choices, not just process improvement.

The bad news of this diagram is that to succeed in any technology adoption, you have to make the right decision about what you’re adopting (in this case, the approach to process improvement and the reference model you intend to use), and you have to implement that decision correctly. The good news of this diagram is that by treating these two actions separately, you can be a little more conscious in both your decision-making and your implementation, which we find leads to better outcomes.

Figure 5-3: Demographic view

The stages of DLI are illustrated in Figure 5-5 and defined in Table 5-1.

Besides the decision implementation model, the other basis for the DLI life cycle is the adoption commitment curve (Figure 5-6). It shows the stages that most individuals and groups go through when approaching adoption of a new set of practices or a new technology.

Figure 5-4: Decision/Implementation and Failure/Success modes

The first three stages—Contact, Awareness, and Understanding—are facilitated primarily via the support of communication mechanisms such as Web sites, conversations with people who have used the approach, seminars, workshops, and training events.

The remaining stages—Trial Use, Adoption, Institutionalization, and Internalization—are facilitated primarily via the support of implementation mechanisms. These include procedures, new measures and controls, policies, employee orientation programs, changes in the organization’s reward system, and continuing communication mechanisms to ensure that those trying the new practices are encouraged that management intends for them to stick.

The focus of the Decide and Try stages of DLI are to get you through Contact, Awareness, Understanding, and Trial Use. Analyze, Commit, and Reflect also support Trial Use and are meant to move you into Adoption and Institutionalization for the particular set of practices you’re working on in this cycle.

Figure 5-5: DLI

Table 5-1: DLI Stages

Figure 5-6: Adoption Commitment Curve

In this way, we hope to avoid the common problem of trying to move immediately to Adoption types of actions when some of the actions and elements that support getting through Contact, Awareness, Understanding, and Trial Use have been ignored.

5.1 Decide

The Decide stage asks you to think explicitly about and make different aspects of the decisions needed to implement process improvement successfully. You’ll revisit this part of the life cycle each time you complete a cycle of improvement and want to go further.

5.1.1 Decision 1: Decide Whether Pi Can Help

Why am I thinking about this?

It is always good to list the reasons you want to pursue process improvement. In Part I, we talked about reasons we believe are appropriate. The main issue to understand as clearly as possible is how PI is going to impact your business positively. But beware complacency. As quality guru W. Edwards Deming said, “It is not necessary to change. Survival is not mandatory.”

Business goals that make this worth thinking about

In CMMI Distilled,1 the authors describe how CMMI supports several common business goals. Table 5-2 summarizes those points. You might use it as a starting place for your analysis.

1. Ahern, Dennis, Aaron Clouse, and Richard Turner. CMMI Distilled: A Practical Introduction to Integrated Process Improvement. 2d ed. (Boston: Addison-Wesley, 2004).

Table 5-2: CMMI Impacts on Business Goals

Does it fit?

Every decision involves some risks, so it’s important to identify those in your environment. In Chapter 9, we introduce the technique of Readiness and Fit Analysis (RFA). One of its main uses is to identify the non-technical risks associated with adopting a new technology or set of practices. Early in your decision making, you will want to perform a Readiness and Fit Analysis against CMMI (or the reference model you’ve chosen) to see how well it fits with your current organizational state and to identify the risks that you will have to mitigate and monitor as you go through your adoption.

Note that we’ve included only the Technology Assumptions Table—one of the elements of RFA—for CMMI. You’ll have to create your own (usually with the help of someone who understands the reference model you’re using very well) if you’re using a different model, such as ISO 12207.

5.1.2 Decision 2: Decide To Do It

When you’ve gotten an idea that process improvement may be a good fit for your organization (or if you’re in the position of being mandated to use CMMI or another model), you need to make the decisions that will get you started on the path toward the next stage: Try.

You have to think about three questions, which we elaborate in the following sections.

Where do I start?

This question leads to more questions… more decisions!

Do I want to use a model to guide me?

Most people who have not done process improvement before decide that they would rather approach this with the help of some kind of process reference model (like the ones we talked about in Chapter 2), rather than use one of the techniques that depends on your analyzing your problems and coming up with unique solutions to them.

That’s the assumption we’re following in this book. So the question becomes “Which one?” For some readers, this choice has already been made for you: Your market or a parent organization has mandated the use of a particular model.

If you’re not in that situation, you will have to choose a model to try. Use the information in Chapter 2 to help you decide which model makes the most sense for your situation, and use the references in Chapter 15 and the bibliography to get more information about the two or three models that seem most relevant to you.

A few things you need to know about the model you choose are

• What aspects of my organization’s work are supported by the model?

• What kinds of skills does the model assume that I have available for implementation of its practices?

• What kinds of support (consulting, training, books, trade journals, and so on) are available for users of the model?

• What did organizations similar to mine experience when they used the model?

One book that does a nice job of laying out several possible models and comparing them for you is called Systematic Process Improvement Using ISO 9001:2000 and CMMI, by Boris Mutafelija and Harvey Stromberg.2

2. Mutafelija, Boris and Harvey Stromberg, Harvey. Systematic Process Improvement Using ISO 9001:2000 and CMMI. (Boston: Artech House Publishing, 2003).

Although the title makes it seem that the book deals only with ISO 9001 and CMMI, it gives good coverage to other standards, including ISO 12207.

Which pieces should I try first?

For this section, we’re assuming you’ve decided that CMMI is a reasonable fit for your organization to try as the basis for your process improvement effort. We make that assumption somewhat selfishly, because the technique we’re going to introduce, model-based business analysis, needs an example to work from.

The purpose of model-based business analysis is to help you figure out which pieces of the model—in this case, CMMI—you want to try first. This decision is important for several reasons:

• All the reference models we mention in Part I are too big to take on all at once, especially if your organization is a small one, so you have to decide which pieces you’ll try first.

• Presumably, your organization is not running perfectly, and there are things that you would like to improve. If you do a good job of matching model elements to the problems you’re facing, you can potentially solve near-term problems at the same time that you’re “trying on” the practices of the model you’ve chosen. In our experience, it’s never a bad thing in business to meet two objectives with a single action!

• If you randomly pick elements of the model (particularly CMMI) to work on, you may miss some inherent dependencies that could offer you leverage if you chose more wisely.

You need three resources to conduct this analysis:

• A moderator/trainer who is knowledgeable about CMMI and connecting it to business issues

• The materials from the Huntsville CMMI pilots used to conduct this analysis: the CMMI overview presentation materials and the business analysis presentation materials (available from the SEI at www.sei.cmu.edu/ttp/publications/toolkit)

• Participants for the workshop who have a useful perspective on the activities and practices being used in the organization

There is a bit of the “chicken and egg” syndrome here. You probably won’t know exactly which projects to involve until you’ve done this kind of business analysis. On the other hand, the people you choose to participate in the business analysis typically drive the set of issues to be ones that will solve their problems. So when you are selecting people to participate in the business analysis, pick those whom you think (1) will be willing to do something proactive to improve their project’s situation and (2) will benefit, at least intuitively, from the kinds of topics covered in CMMI or the model you’ve chosen.

What you do in this analysis is combine some overview training on the contents of CMMI with some discussion of the typical kinds of problems that different clusters of CMMI practices (called Process Areas in the model) are expected to solve. Through this discussion, the group performing the analysis generally starts to recognize particular sets of issues that the model addresses and that currently are causing pain within the organization or within a subset of projects. The mapping of the organization’s business problem with CMMI content allows you to do an initial filtering of the model from 22 potential Process Areas to 8 or 10 (usually; sometimes fewer, once in a while a couple more).

Then you look at that filtered set more closely, based on thinking about what the problems you’re facing in each of those process areas actually are. This is where a knowledgeable consultant is really essential; he or she is the one who ensures that the problems are correctly mapped to the Process Areas and can explain model content that isn’t as clear to you when you’re trying to think about your problems in relation to the model. A consultant will also help you further prioritize your list of potential Process Areas based on some of the inherent dependencies in the model that you’re not likely to be familiar with at this point, helping you leverage your initial efforts even more.

After you have filtered your list again down to four or five Process Areas, you start looking at some of the issues covered further on in DLI: which projects would be good candidates for testing new processes in the selected areas, and which projects are (or soon will be) at a point that is appropriate for one or more of the selected Process Areas. Again, an experienced process improvement facilitator is a great asset in this step; this person can listen to your project candidates and do a good job of asking questions that help you pick the one(s) most appropriate for your situation.

When you’ve completed the analysis, you can move on to your next decisions.

Although this analysis technique is not the only way to choose candidate model topics to address while you’re thinking about model adoption, it’s one that worked very well in pilot work on applying CMMI in small settings, and feedback we’ve gotten from people who have tried this approach in their own organizations has been very positive.

If you’re not using CMMI…

If you are using some reference model other than CMMI, we recommend that you work with someone who knows that model well to build the same kind of translation of the model into business symptoms that we’ve demonstrated using CMMI (see the pilot kickoff materials referenced in the preceding section). You may be able to do this yourself just by looking at the contents of the model you’re considering. Usually, however, because you are a new user of the model, you will miss nuances that could have impact on your decision about which pieces to try. You may also be able to find some of this information in presentations or articles written about the model you’ve chosen.

5.1.3 Decision 3: Decide Where To Try It

When you’ve decided which pieces of CMMI you plan to tackle first, you have to decide who will be involved in making the improvements.

This is one place where DLI differs from some other life cycles. At this point, we’re not suggesting that you put together a whole group to do process improvement (often called an Engineering Process Group, or EPG). What we’re suggesting is that you find the people who can make changes at the project level in the areas you’ve identified, so that you can see whether the model helps you (1) make appropriate changes productively and (2) fix the problem you think it will fix.

This means that you need to choose projects and team members who will be doing something about the topics covered in the Process Areas you’ve chosen in the near term. If you want to do something to improve Project Planning (one of the Process Areas of CMMI), for example, you need to have a project that’s getting ready to go into planning. This sounds obvious, but you’d be surprised how many people pick a Process Area and then pick a project that can’t do anything about that Process Area for months! Some Process Areas, such as Configuration Management, have something going on at almost any stage in a project, so they may be easier to fit to a project.

Table 5-3 generally associates Process Areas for Maturity Levels 2 and 3 with a typical product development life cycle.

Table 5-3: General Association of PAs with Product Life Cycle

How many and which people should be involved depends fairly heavily on what you’ve decided to improve initially. Usually, the manager of the project and the key staff members who are involved in the processes being worked with would be the minimum set of people to include on an improvement team.

There are some other considerations in selecting projects and teams to work on process improvement. In particular, the amenability of the people involved to try new things and to be willing to be your “guinea pigs” is a key issue. One thing you can do to understand which projects or teams will be most likely to succeed is to do an adopter analysis. We cover this technique in Chapter 13.

Get team/project buy-in

In Chapter 11, we introduce a particularly effective model for analyzing and supporting teams: the Drexler-Sibbett Team Performance model. This is one of the many times you’ll want to use it. When you start selecting the projects to work your improvements, you generally have a choice of more than one project for a particular improvement area. Spending some time working with the candidate project teams to determine which team is the best fit (yes, you can do a team-level RFA at this point, if you need to) for the improvement project is worthwhile. Going through the early stages of the Team Performance model is one way to see quickly how each project team would approach the improvement effort. Especially for your first pilot, a team that is committed to working with the new ideas to solve the identified problem is a huge step toward success. After the first pilot, teams that are less committed are more likely to adopt if the first one was successful.

5.1.4 Decision 4: Decide When To Try It

Some of the issues about “when to try” are covered in the CMMI business analysis referenced in the preceding section. However, there are some additional things to think about beyond those covered in the business analysis.

How do the risks I’ve identified affect my ideas?

By the time you get through choosing a set of three or so Process Areas and the projects and people you think should be involved in them, you’re at a good point to step back and compare the risks you identified through your Readiness and Fit Analysis with the PAs and projects you’ve chosen. If the projects you’ve selected reflect or exhibit the risks that you identified, you have a couple of choices:

• Avoid that project, and pick one that doesn’t involve as many risks or less-severe risks.

• Work with that project, but include specific mitigation actions and monitoring to minimize the occurrence and/or effect of the identified risks.

If the risks you’ve identified make it clear that one of the PAs you’ve selected could be a problem, your choices are

• Pick another PA that may not solve as big a problem but reflects fewer risks.

• Work with that PA, but include specific mitigation actions and monitoring to minimize the occurrence and/or effect of the identified risks.

5.2 Try Initial (Additional) Model Elements

This is the real hands-on work of DLI. You’ll need to plan carefully and communicate well so that you don’t alienate the practitioners. Here’s our checklist of things to do.

5.2.1 Baseline Existing Performance

Before you begin any process improvement initiative, get a baseline of how well the current way of doing things is performing. If you can’t get actual measures (or even guesses from knowledgeable people), look into industry standards and benchmarks. You want to be able to measure yourself against something to show progress. Otherwise, any improvement can be discussed only anecdotally.

You should use whatever measures are available to you, especially in the first few cycles. A heavy measurement infrastructure may be the straw that breaks your supporter’s back. Try to find measures that are already collected (defects, cycle time, customer responses, and so on).

5.2.2 Develop The Guidance Needed

This may be the first work you do that’s visible to practitioners: creating and documenting the new or changed process. Information Mapping (described in Chapter 12) and technology adoption methods (described in Chapter 13) can be very useful in this work. Some other things to think about in developing guidance are:

• Make sure that you capture any rationale you want to communicate to the practitioners as you design the changes so that the changes don’t get lost in the shuffle.

• Develop work aids to help practitioners execute the improved process, as well as some initial training material.

• Apply the adopter-analysis and value-network approaches in Chapter 13 to identify and include key stakeholders. This is extremely helpful in getting the process right, stating rationale, and enabling speedy adoption.

• Keep it lightweight. Taking a cue from the agilists, we believe that guidance should be the smallest amount possible of documentation (things practitioners have to read and understand) and ceremony (things that have to be done other than the task at hand). The only objective is to ensure understanding and compliance. Don’t spend time writing novels (or even short stories). Write brief, concise descriptions, and use graphics (like swim-lane charts) to the best advantage.

• Keep your notes, and document your assumptions. Discussions always come up after the fact. Good notes are helpful in handling disputes about what was said when.

• Initially, use a trained facilitator, if at all possible. People with training in process capture and facilitation can save you a great deal of grief and usually save you considerably more money than they cost.

• Identify any risks that may result from the new process. Change always has some associated risk. Don’t hide it. If possible, also identify ways to mitigate the risks, or build fail-safe steps into the process.

• Develop an implementation plan. As you document your new or improved processes, capture ideas for rolling it out, and get the practitioners to help you help them be successful. This isn’t an Integrated Master Plan for an aircraft carrier; it’s a time-ordered list of who’s doing what by when. The planning process is more important than the documentation format and content.

• Identify the closure criteria. Make sure that you have a documented and agreed-upon way of determining when this specific phase is over. It usually is something like “The team is implementing the process correctly, and all necessary data has been collected.”

5.2.3 Train Users On The New Guidance

You can’t ask people to do something they don’t understand how to do, and it’s best that they know why and how it fits into the larger scheme of things.

You can do this through training. You have developed the process artifacts; now use them to train your people. Take the time to make sure that they understand clearly so that the improved process is implemented as you planned. Make sure that the practitioners know how they can suggest changes that they think would make the process even better for use in the next cycle. This is especially important if they haven’t been involved at the beginning. The Satir change cycle’s Integration and Practice stage (described in Chapter 13) can guide what kinds of things you include in your training experience.

5.2.4 Monitor Deployment

Execute your plan. Use the list of risks produced as a tickler during the implementation. If you see the possibility that a risk is surfacing as a problem, act quickly. It may be necessary to delay some part of the implementation until the risk or problem can be resolved.

As you proceed, take notes on what is done each day and on any feedback or problems that arise. Simply keeping a blog or journal should suffice for this part. If there is a large implementation team, it may be useful to have team members contribute as well. A shared internal blog can be a productive way of facilitating this kind of informal communication.

5.2.5 Complete Initial Cycle

When you have accomplished the planned activities, and your closure criteria have been met, you can close out the phase. Be sure to gather any measures you’ve defined or to collect existing organizational measures that are relevant. Also collect any anecdotes from the practitioners, customers, and implementers for later review.

5.3 Analyze

You’ve finished the implementation and piloting of a process improvement increment. In this step you decide whether the result was good enough to deploy across a larger part of the organization. You might also decide that there need to be changes and another pilot run before committing to the deployment. To make this decision, you need to review the goals set, measures collected, and anecdotal evidence gathered, and then draw some conclusions. In some cases, this analysis phase is fairly cut and dried and you can see clearly whether the package as piloted was effective. In other cases, unforeseen problems or external events may have impacted the trial and need to be factored into the results, or the trial may need to be repeated. Where there are large numbers of participants, it may take some time to collect and check the data, and there may need to be a more formal analysis.

You should consider essentially four questions:

• What worked or didn’t work?

• How well did we follow our plan?

• Do there need to be significant changes?

• What do the measures tell us?

5.3.1 What Worked Or Didn’t Work?

There is always a certain level of intuitive processing in evaluating the effectiveness of some activity. Without resorting to measures per se, what do you feel went right in this process pilot? What went wrong? What part was inadequate?

This intuitive exercise is important because much of process improvement is about change management, and the success of change is essentially predicated on human perceptions. You need to know whether you (and the other participants) feel that this pilot was successful. You need to identify the places that could be improved, either for a retrial or for the next improvement cycle. In Chapter 15, we present another approach to understanding what worked or didn’t work: the Chaos Cocktail Party. Many people find it a useful approach to looking at a great deal of evaluation data in a short period of time and getting an initial prioritization of the data.

5.3.2 How Well Did We Follow Our Plan?

In evaluating the trial, you have to examine whether you did what you said you were going to do when you planned the activity. If you changed something that might have impacted the outcome, you need to understand why it was changed. Was the planned activity too difficult or unclear? Did an external event interfere? Was the planned activity ill advised or improper? All these factors have a bearing on whether you can declare the trial a success.

This is also where you take a look at the goals and measures you set up for the project initially, to determine how much progress you have made against them. See Chapters 9 and 15 for details on setting and measuring against your goals.

5.3.3 Are Significant Changes Needed?

In analyzing the results, you look for anything that stands out as something to change for the next improvement cycle. At this point, the key things to change should be in the process package itself, although implementation changes could be considered. Was the guidance clear and concise, or does it need to be revised? Were the activities the right ones? Did the process as implemented do the job, or are there shortcomings that need to be addressed?

5.3.4 What Do The Measures Tell Us?

Finally, after you’ve evaluated all the other information, you look at the empirical data. Does it show that your new process was better than the old baseline (or benchmarks)? Is the change in performance sufficient to cover the cost to deploy? Are the measures you collected sufficient to determine any of the above? Do you need different measures or different collection strategies?

5.4 Commit

This is it. Now you have to decide if the new (or changed) process or artifact is ready to be used by a broader group in the organization. There are some differences in the decisions if this is the first time through the cycle.

5.4.1 First Time Through

After you’ve gone through a test or pilot of implementing CMMI-based practices, it’s time to decide whether and how you will deploy these new practices into the rest of the organization in such a way that they will become institutionalized.

For a small organization, this could be relatively trivial; the whole organization may have been involved in trying the Process Areas you picked. But even in the case where the pilot is the organization, there are still deployment steps you need to take.

In particular, you need to figure out what transition mechanisms need to be added to your basic process description to help this new set of practices stick in the organization. You have two basic categories of transition mechanisms to think about:

• Communication mechanisms—things that make it easier to understand what the new processes are about and what the requirements for performance are

• Implementation support mechanisms—methods, tools, and techniques that are needed to make it easier to implement the practices

If you’re working with the Measurement and Analysis PA, for example, you’ll consider procedures for storage and handling of measurement data. A communication mechanism you may need is a template for providing synthesized management reports for the monthly company management meeting.

An example of a possible implementation support mechanism for this PA is the database needed to store the measurement data being collected.

This also may be the point at which you rewrite your initial process description related to the PAs you’ve been working on to reflect your initial experiences.

5.4.2 Subsequent Cycles

After you’ve completed a few cycles of improvement, the Commit activities are likely to be related to embedding the new practices into your improvement infrastructure, as well as to establishing the transition mechanisms to ensure widespread deployment to the relevant practitioners.

Especially in a medium-size or larger organization, this phase involves planning the sequence and cycles of deployment that result in a robust implementation.

If you look back at the adoption commitment curve, you can think of Commit as the place where you’re trying to move from Trial Use into Adoption, with all the transition mechanisms (especially implementation mechanisms) that are attendant to that stage. What this means is that your Commit stage is the place where you’ll really be concentrating on building and deploying improvement infrastructure elements such as process asset libraries (PAL), Measurement Repositories, training courses, and job aids for particular processes. A good approach at this point is to go through the list of transition mechanisms described in Chapter 13 and reconsider some of the things in them that you rejected for your first improvement journey through DLI. You may find that now, when you’re ready to commit to a larger improvement effort, some of them make more sense to develop or acquire.

5.5 Reflect

One of the most important characteristics of DLI is the Reflect stage. If process improvement is valuable, improving the improvement process is doubly valuable and requires the same careful attention as the other activities. Taking the time to look back at what you’ve accomplished and to learn from what you see is a rarely performed but fundamental step in your PI journey.

Reflect is about adding “double-loop learning” to your process. This is a well-known concept in organizational learning3,4 that indicates a deeper learning than we typically engage in. Single-loop learning is when we see an error, make the correction needed, and then move on and don’t think about that error anymore. Double-loop learning, on the other hand, is when we see an error, correct it, and then try to understand how it happened so we can prevent it in the future.

3. Argyris, C., and D. Schön. Theory in Practice: Increasing Professional Effectiveness. (San Francisco: JosseyBass, 1974).

4. Argyris, C., and D. Schön. Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Perspective. (Reading, Mass.: AddisonWesley, 1978).

In the case of process improvement, you want to look at the process you used to get through the DLI cycle and think about what you could do next time to make it easier or more effective.

5.5.1 Perform Project Retrospective

Project retrospective techniques are very useful in supporting reflection. These techniques provide a set of areas or questions to think about to guide your reflection process. Some people call this process a post-mortem, although most of the time when they use that term, it’s because the project has died. We agree with those who think that project retrospective is a more accurate and emotion-neutral label for this type of activity. For those times when you really do want to emphasize that something ended badly, and you need to process what happened, we have a technique that has proved to be useful, based on the “CSI” (Crime Scene Investigation) television series. SuZ learned this technique at a North American Simulation and Gaming Association (NASAGA) conference several years ago and has successfully adapted it for use in root-cause analysis.5

5. Garcia, Suzanne, and Shawn Presson. “Active Learning Approaches for Process Improvement Training: An Interactive Workshop,” presented at SEPG 2004. www.sei.cmu.edu/ttp/presentations/death-byslides. (Pittsburgh: Carnegie Mellon University, 2004).

The basics of the CSI technique are to use masking or other tape to lay out a “body” shape (see Figure 5-7 for a variety of choices) and then put sticky notes with the “symptoms” of the death all over the body (in large print, so that it’s readable when you’re standing up!). Your participants write their ideas of the “cause of death” (the root cause) on index cards, and you can use different techniques from there to prioritize, discuss, and further process the root-cause ideas. SuZ’s colleague and friend Shawn Presson created a series of archetypal “deaths” that he has given us permission to post on the Addison-Wesley Web site for you to use (or just chuckle at). The procedures for CSI and related techniques are included in Chapter 15.

A comprehensive resource for engaging in and facilitating project retrospectives is Norm Kerth’s book Project Retrospectives: A Handbook for Team Reviews.6 It not only provides tools and techniques for setting up and running retrospectives, but also provides help for staff members who want to justify holding a retrospective.

6. Kerth, Norm. Project Retrospectives: A Handbook for Team Reviews. (New York: Dorset House, 2001).

5.5.2 Repeat Decision-Making/Implementation Process Until You Achieve Desired Results

As in any improvement cycle, if you’re serious about continually improving your performance, you have to go through the cycle multiple times as you learn more about how to improve and about what needs to be improved.

Figure 5-7: Archetypal death cartoons (adapted from Garcia and Presson, “Beyond Death by Slides” tutorial)

What is likely to happen in the beginning is that you will do the business analysis and figure out a couple of Process Areas (if you’re using CMMI) that will help you solve current business problems. You will work on those areas and solve the identified problems. When these problems are out of the way, you will be able to see and pay attention to other problems that were not as obvious before.

So you go through your decision process again to determine, at this next point in time, what will be the most business-benefiting processes for you to work on next.

5.6 Summary Of Part II

In Part II, we’ve presented our two favorite “maps” for getting you started on a successful process improvement effort: CMMI as your model map and DLI as your improvement life-cycle map. We’ve also recommended some other resources for learning more about CMMI. If you’re a sponsor, you’ll probably go only as far as to read something like CMMI Distilled, but if you’re the person or group in charge of getting a sustainable improvement effort going, you’ll need to go farther than that—probably to a formal class of some sort. At some point, you’ll probably read the model itself. Let us remind you that most of the material in the 700-plus pages of the model is informative material, meant to help you understand the much smaller proportion of material that is normative. (These are terms used by ISO. Normative is the part of the standard against which an organization would be evaluated; informative is “just for your information; use it if you find it relevant” material.)

We expect DLI’s emphasis on decisions to have two effects on an organization:

• Helping organizations understand that they have many choices encourages them to understand that they are not meant to slavishly follow the “dogma of CMMI.”

• On the other hand, it also makes them realize that they probably need more information than they have to make those choices.

The good news about the latter effect is that it inspires the organization to take education events surrounding process improvement or CMMI more seriously, because they know why they need that particular education. The bad news is that if the organization is resource constrained, some of that information can seem to be out of reach. Although we won’t claim that this book will address all your learning needs (we only scratch the CMMI surface), we do intend that it address some of the areas that are hard to find resources for in book form (such as determining adoption risk).

If you’re a sponsor of a CMMI effort, this may be enough for you to feel ready to find a champion to take the effort forward. But we encourage you to read the next part as well. In it, we provide a fictional case study that might help you make the transition from “What is it?” to “How would it feel to do this?” And we provide some advice on survival that, although it will be more important to the champion of the effort, will probably have some utility (and maybe even some amusement) for you.

If you’re the leader of a process improvement effort, your journey is just getting started, and the next section will help you preview what’s ahead so that you won’t be (as) surprised when you start seeing what’s going on with improvement in your organization.

Illustration from The Travels of Marco Polo by Witold Gordon (1885–1968)